Development and Validation of the Latvian Version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Dental Patients with Aesthetic, Functional and No Treatment Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. OES Translation

2.2. Patient Sample

2.3. Reliability

2.4. Validity

- 1.

- Have you noticed a tooth that does not look right? (Item 3)

- 2.

- Have you felt uncomfortable about the appearance of your teeth, mouth or dentures? (Item 22)

- 3.

- Have you avoided smiling because of problems with your teeth, mouth or dentures? (Item 31)

2.5. Group Comparisons

3. Results

3.1. Translation

3.2. Study Participants and Scores

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Validity

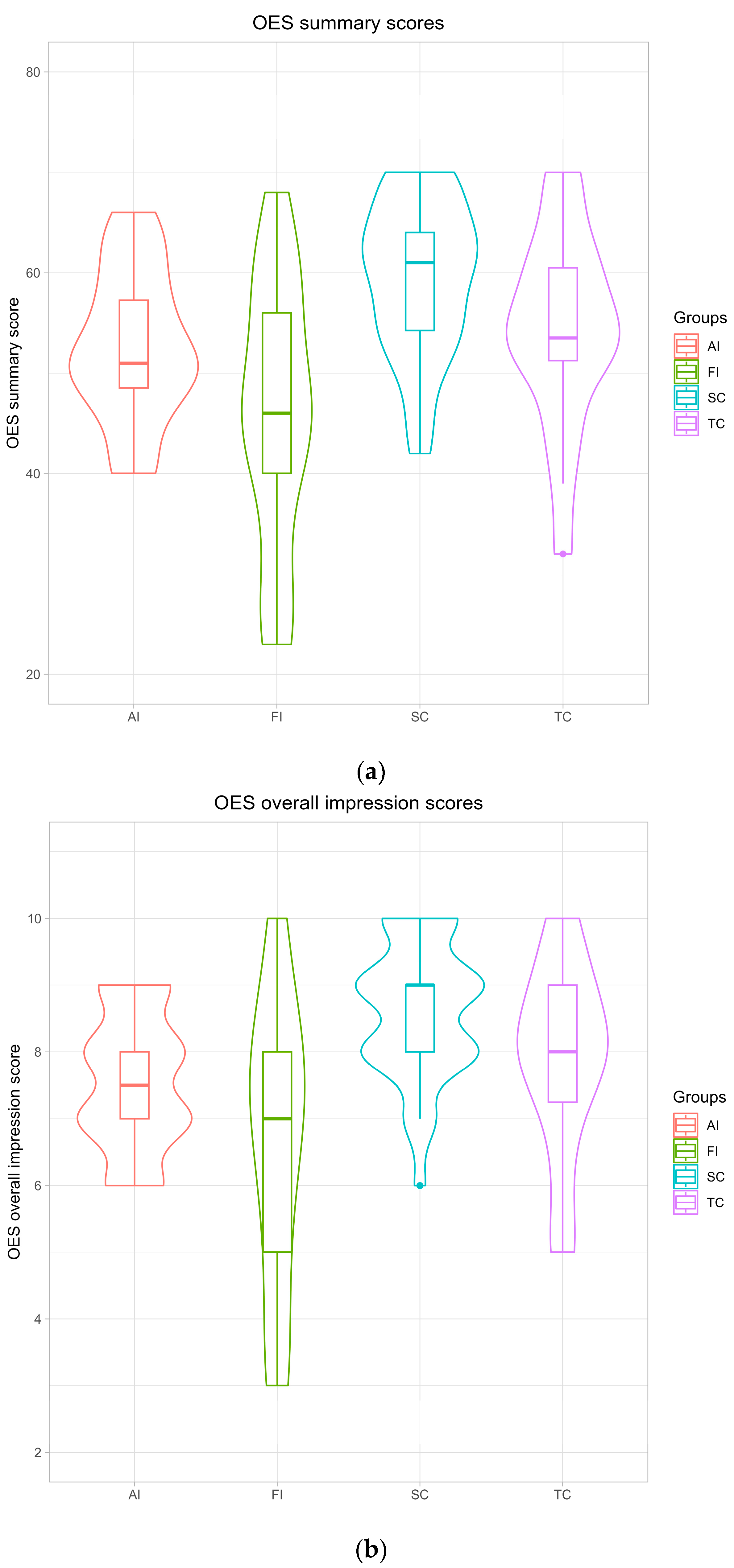

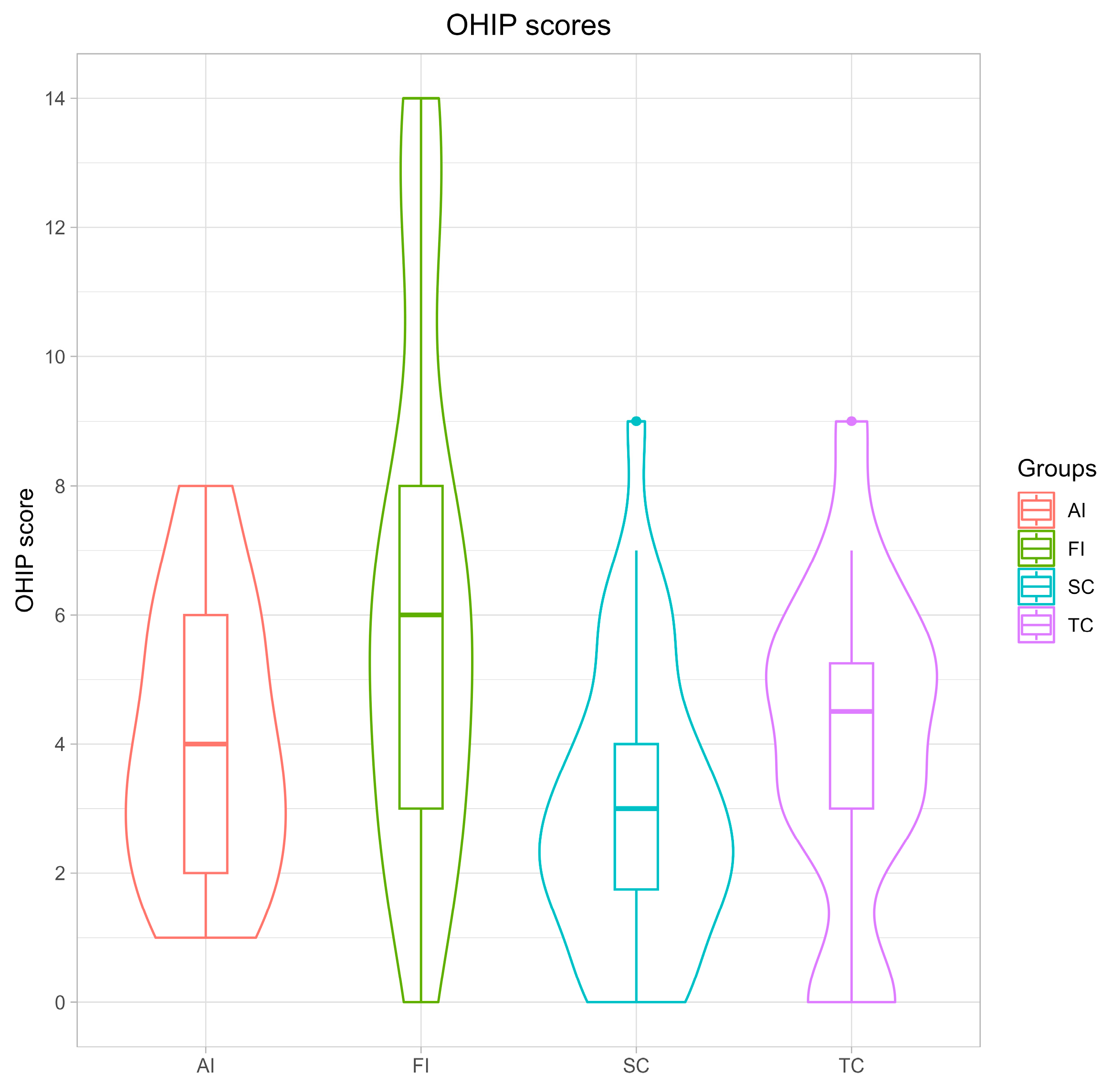

3.5. Group Comparisons

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samorodnitzky-Naveh, G.R.D.M.D.; Geiger, S.B.D.M.D.; Levin, L.D.M.D. Patients’ satisfaction with dental esthetics. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 138, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavric, A.; Mirceta, D.; Jakobovic, M.; Pavlic, A.; Zrinski, M.T.; Spalj, S. Craniodentofacial characteristics, dental esthetics–related quality of life, and self-esteem. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 147, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokich, V.O.; Kiyak, H.A.; Shapiro, P.A. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 1999, 11, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marachlioglou, C.R.M.Z.; Dos Santos, J.F.F.; Cunha, V.P.P.; Marchini, L. Expectations and final evaluation of complete dentures by patients, dentist and dental technician. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrashtehfar, K.I.; Bryant, S.R.; Assery, M.K.A.; Isola, G. Patient Satisfaction in Medicine and Dentistry. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 6621848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Spencer, A.J. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent. Health 1994, 11, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larsson, P.; Bondemark, L.; Häggman-Henrikson, B. The impact of oro-facial appearance on oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2021, 48, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, P.; John, M.T.; Nilner, K.; Bondemark, L.; List, T. Development of an Orofacial Esthetic Scale in prosthodontic patients. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 23, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, P. Methodological studies of orofacial aesthetics, orofacial function and oral health-related quality of life. Swed. Dent. J. Suppl. 2010, 38, 11–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wetselaar, P.; Koutris, M.; Visscher, C.M.; Larsson, P.; John, M.T.; Lobbezoo, F. Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale (OES-NL) in dental patients with and without self-reported tooth wear. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2015, 42, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.A.; Kämäräinen, M.; Silvola, A.-S.; Marôco, J.; Peltomäki, T.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Orofacial Esthetic Scale and Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties of the Finnish version. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021, 79, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persic, S.; Milardovic, S.; Mehulic, K.; Celebic, A. Psychometric properties of the Croatian version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale and suggestions for modification. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 24, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderlein, G. Fleiss, J.L.: The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. Wiley, New York—Chichester—Brislane—Toronto—Singapore 1986, 432 S., £38.35. Biom. J. 1988, 30, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, P.; John, M.T.; Nilner, K.; List, T. Reliability and validity of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in prosthodontic patients. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 23, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Pugača, J.; Urtāne, I.; Pirttiniemi, P.; Rogovska, I. Validation of a Latvian and a Russian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile for use among adults. Stomatol. Balt. Dent. Maxillofac. J. 2014, 16, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Companies: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sadrhaghighi, A.; Zarghami, A.; Sadrhaghighi, S.; Mohammadi, A.; Eskandarinezhad, M. Esthetic preferences of laypersons of different cultures and races with regard to smile attractiveness. Indian. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 28, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imafuku, R.; Nagatani, Y.; Shoji, M. Communication Management Processes of Dentists Providing Healthcare for Migrants with Limited Japanese Proficiency. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 14672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Quiñonez, C. Straight, white teeth as a social prerogative. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 782–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiaku, S.; Millar, B.J. Maxillary Midline Diastemas in West African Smiles. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.L.; Pérez, B.P.; Sánchez, J.A.S.; Acinas, M.M.R. Dental aesthetics as an expression of culture and ritual. Br. Dent. J. 2010, 208, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchi, V.; Barbieri, P.; Pradella, F.; Focardi, M.; Bartolini, V.; Norelli, G.-A. Dental Ritual Mutilations and Forensic Odontologist Practice: A Review of the Literature. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2015, 49, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić, M.; Ignjatović, A.; Gligorijević, N.; Jovanović, M.; Đorđević, N.S.; Đerlek, A.; Igić, M. Development and psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijmer, J.G.; Mol, B.W.; Heisterkamp, S.; Bonsel, G.J.; Prins, M.H.; van der Meulen, J.H.P.; Bossuyt, P.M.M. Empirical Evidence of Design-Related Bias in Studies of Diagnostic Tests. JAMA 1999, 282, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rella, E.; De Angelis, P.; Nardella, T.; D’Addona, A.; Manicone, P.F. Development and validation of the Italian version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale (OES-I). Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulina; Dhawan, P.; Jain, N.; Khan, U. Validation, Adaptation and Assessment of Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Hindi Language. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2024, 35, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaokutan, I.; Senol, H.; Aksoy, D.; Ayvaz, I.; Cifci, H. Development and psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2024, 36, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbashi, V.; Čelebić, A.; Staka, G.; Hoxha, F.; Peršić, S.; Petričević, N. Psychometric properties of the Albanian version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale: OES-ALB. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reissmann, D.R.; Benecke, A.W.; Aarabi, G.; Sierwald, I. Development and validation of the German version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strajnic, L.; Bulatovic, D.; Stancic, I.; Zivkovic, R. Self-perception and satisfaction with dental appearance and aesthetics with respect to patients’ age, gender, and level of education. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2016, 144, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavranović-Glamoč, A.; Kazazić, L.; Strujić-Porović, S.; Berhamović, E.; Džonlagić, A.; Zukić, S.; Jakupović, S.; Tosum Pošković, S. Satisfaction and attitudes of the student population about dental aesthetics. J. Health Sci. 2021, 11, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Närhi, L.; Mattila, M.; Tolvanen, M.; Pirttiniemi, P.; Silvola, A.-S. The associations of dental aesthetics, oral health-related quality of life and satisfaction with aesthetics in an adult population. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Gender | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

| All | Both | 101 | 20 | 85 | 38.25 | 16.64 |

| M | 43 | 20 | 75 | 39.72 | 17.4 | |

| F | 58 | 20 | 85 | 37.16 | 16.12 | |

| Aesthetically impaired (AI) | Both | 24 | 25 | 63 | 40.83 | 10.38 |

| M | 8 | 31 | 61 | 43 | 9.9 | |

| F | 16 | 25 | 63 | 39.75 | 10.75 | |

| Functionally impaired (FI) | Both | 25 | 22 | 73 | 49.6 | 13.79 |

| M | 14 | 22 | 73 | 50.21 | 15.89 | |

| F | 11 | 32 | 68 | 48.82 | 11.26 | |

| Dental students without treatment (SC) | Both | 34 | 20 | 26 | 21.03 | 1.42 |

| M | 14 | 20 | 23 | 20.71 | 0.91 | |

| F | 20 | 20 | 26 | 21.25 | 1.68 | |

| Previously treated patients (TC) | Both | 18 | 31 | 85 | 51.56 | 15.21 |

| M | 7 | 37 | 75 | 53 | 11.65 | |

| F | 11 | 31 | 85 | 50.64 | 17.6 |

| ICC (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| OES summary | 0.80 (0.59; 0.90) |

| OES overall impression | 0.81 (0.60; 0.91) |

| Cronbach’s Alpha (If Item Deleted) (95% CI) | Corrected Item Correlation | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 0.91 (0.88; 0.93) | 0.89 (0.85; 0.92) | 0.90 (0.87; 0.93) | 0.88 (0.84; 0.91) | 0.89 (0.85; 0.92) | 0.89 (0.85; 0.92) | 0.89 (0.85; 0.92) | 0.9 (0.87; 0.93) | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.64 |

| N | Spearman’s Rank Correlation (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 101 | −0.51 (−0.65; −0.35) |

| Aesthetically impaired (AI) | 24 | −0.35 (−0.66; 0.06) |

| Functionally impaired (FI) | 25 | −0.47 (−0.73; −0.08) |

| Dental students without treatment (SC) | 34 | −0.57 (−0.77; −0.28) |

| Previously treated patients (TC) | 18 | −0.57 (−0.83; −0.10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaile, M.; Skrivele, S.; Larsson, P.; Radzins, O.; Soboleva, U.; Larsson, C. Development and Validation of the Latvian Version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Dental Patients with Aesthetic, Functional and No Treatment Needs. Medicina 2025, 61, 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122180

Gaile M, Skrivele S, Larsson P, Radzins O, Soboleva U, Larsson C. Development and Validation of the Latvian Version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Dental Patients with Aesthetic, Functional and No Treatment Needs. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122180

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaile, Mara, Simona Skrivele, Pernilla Larsson, Oskars Radzins, Una Soboleva, and Christel Larsson. 2025. "Development and Validation of the Latvian Version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Dental Patients with Aesthetic, Functional and No Treatment Needs" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122180

APA StyleGaile, M., Skrivele, S., Larsson, P., Radzins, O., Soboleva, U., & Larsson, C. (2025). Development and Validation of the Latvian Version of the Orofacial Esthetic Scale in Dental Patients with Aesthetic, Functional and No Treatment Needs. Medicina, 61(12), 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122180