The Prevalence of H. pylori Among Jordanian Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Its Association with ABO Blood Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Sample Characteristics

2.4. Blood Sample Collection and Processing

2.5. Expression of ABO Antigens in Blood

2.6. Ethics

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Factors Associated with Diabetes: Logistic Regression Analyses

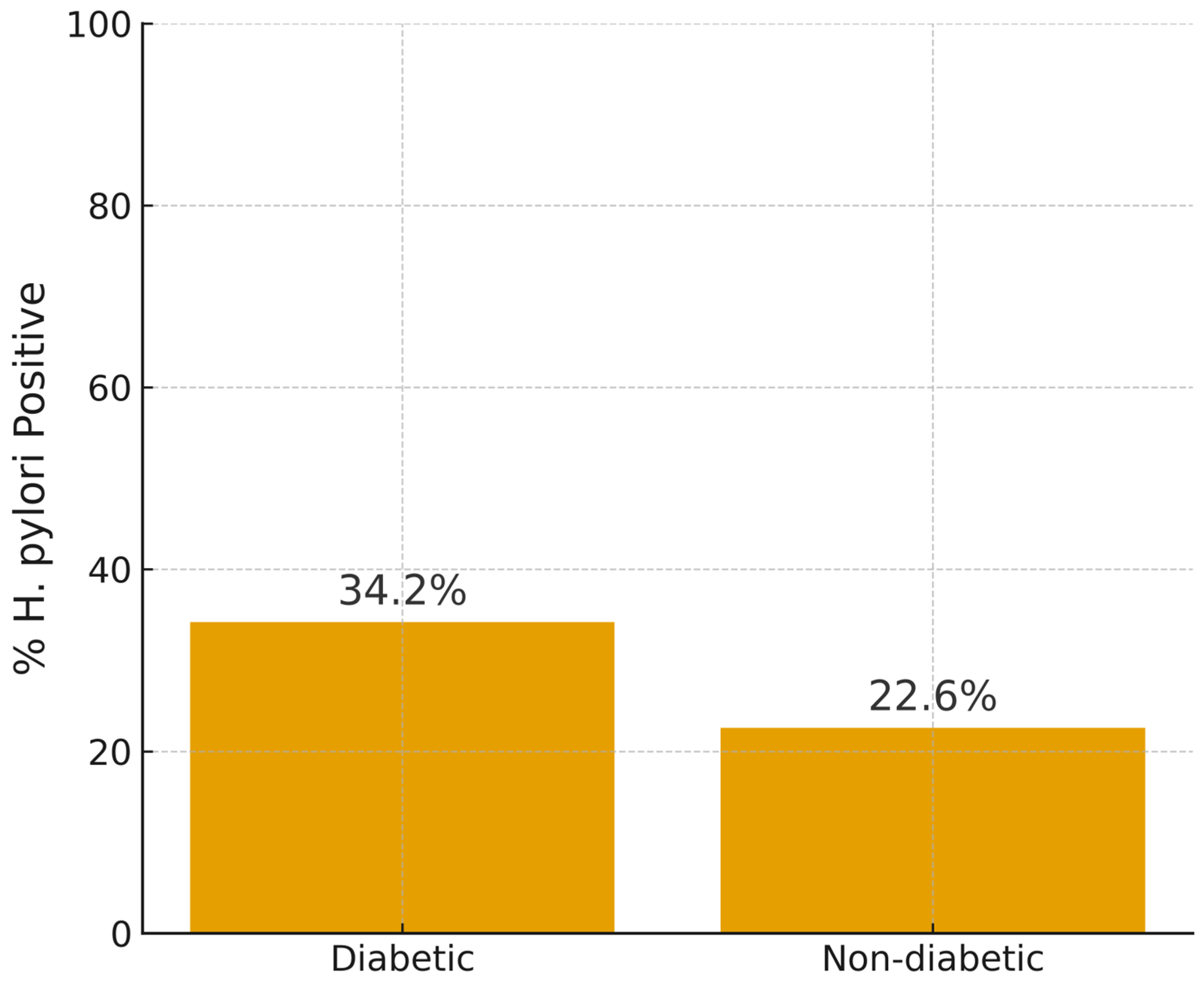

3.3. H. pylori Infection Rates in T2DM Participants and Non-Diabetics

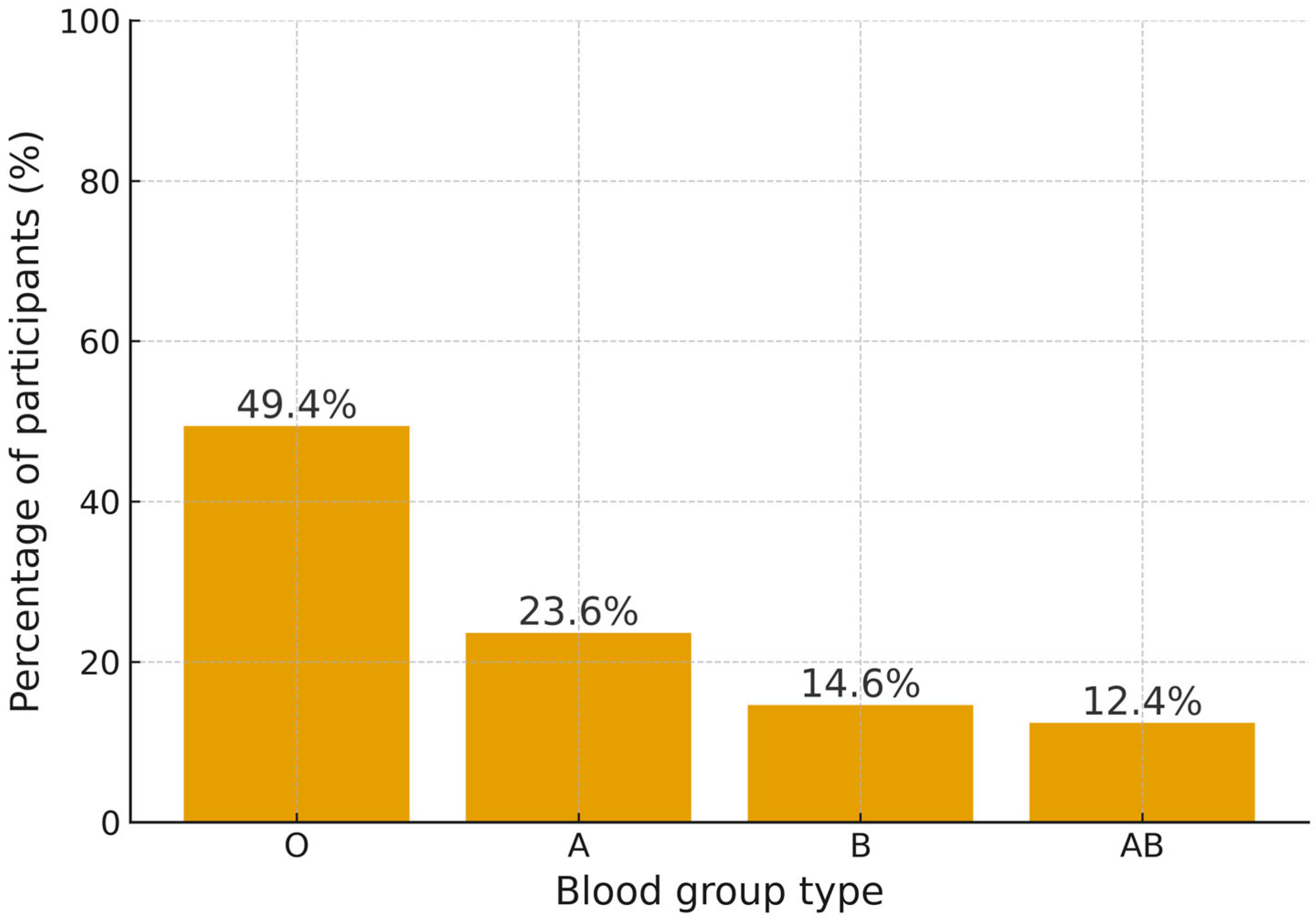

3.4. H. pylori Infection Rates in ABO Blood Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hooi, J.K.; Lai, W.Y.; Ng, W.K.; Suen, M.M.; Underwood, F.E.; Tanyingoh, D.; Malfertheiner, P.; Graham, D.Y.; Wong, V.W.; Wu, J.C. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Ağan, A.F.; Al-Hamaq, A.O.; Barisik, C.C.; Öztürk, M.; Ömer, A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2020, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, F. The Association Between ABO Blood Group Dis-tribution and Helicobacter Pylori Infection: A Cross-Sec-tional Study. Jpn. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alsulaimany, F.A.; Awan, Z.A.; Almohamady, A.M.; Koumu, M.I.; Yaghmoor, B.E.; Elhady, S.S.; Elfaky, M.A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and diagnostic methods in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Medicina 2020, 56, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ta’ani, O.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Lahoud, C.; Almasaid, S.; Alhalalmeh, Y.; Oweis, Z.; Danpanichkul, P.; Baidoun, A.; Alsakarneh, S.; Dahiya, D.S. Socioeconomic and demographic disparities in the impact of digestive diseases in the middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryshnikova, N.V.; Ermolenko, E.I.; Leontieva, G.F.; Uspenskiy, Y.P.; Suvorov, A.N. Helicobacter pylori infection and metabolic syndrome. Explor. Dig. Dis. 2024, 3, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, H.; Abdel-Hafeez, H.; Lotfy, A.; Zidan, H.; Khalil, F. Assessment of the relation between Helicobacter pylori infection and insulin resistance. J. Dig. Dis. Hepatol. 2016, 16, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, E.; Figura, N.; Campagna, M.S.; Gonnelli, S.; Iacoponi, F.; Collodel, G. Sperm parameters and semen levels of inflammatory cytokines in Helicobacter pylori–infected men. Urology 2015, 86, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, C.; Sugimoto, K.; Moritani, I.; Tanaka, J.; Oya, Y.; Inoue, H.; Tameda, M.; Shiraki, K.; Ito, M.; Takei, Y. Changes in plasma ghrelin and leptin levels in patients with peptic ulcer and gastritis following eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-González, C.; Mendoza, E.; Mera, R.M.; Coria-Jiménez, R.; Chico-Aldama, P.; Gomez-Diaz, R.; Duque, X. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum leptin, obestatin, and ghrelin levels in Mexican schoolchildren. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 82, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Anza-Ramírez, C.; Saal-Zapata, G.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Zafra-Tanaka, J.H.; Ugarte-Gil, C.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and antibiotic-resistant infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2022, 76, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.I.; Cockram, C.S.; Ma, R.C.; Luk, A.O. Diabetes and infection: Review of the epidemiology, mechanisms and principles of treatment. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansori, K.; Moradi, Y.; Naderpour, S.; Rashti, R.; Moghaddam, A.B.; Saed, L.; Mohammadi, H. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for diabetes: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, K.; Cui, C.; Wang, X. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with complications of diabetes: A single-center retrospective study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2024, 24, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Z.; Li, J.-Y.; Wu, T.-F.; Xu, J.-H.; Huang, C.-Z.; Cheng, D.; Chen, Q.-K.; Yu, T. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with type 2 diabetes, not type 1 diabetes: An updated meta-analysis. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 5715403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhong, X.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Shang, M.; Jiang, C.; Yang, H.; Zhao, W.; Liu, L. Helicobacter pylori infection associated with type 2 diabetic nephropathy in patients with dyspeptic symptoms. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 110, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benktander, J.; Ångström, J.; Breimer, M.E.; Teneberg, S. Redefinition of the carbohydrate binding specificity of Helicobacter pylori BabA adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 31712–31724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgren, G.; Hjalgrim, H.; Rostgaard, K.; Norda, R.; Wikman, A.; Melbye, M.; Nyrén, O. Risk of gastric cancer and peptic ulcers in relation to ABO blood type: A cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.D.; Sirous, M.; Saki, M.; Seyed-Mohammadi, S.; Modares Mousavi, S.R.; Veisi, H.; Abbasinezhad Poor, A. Associations between seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori and ABO/rhesus blood group antigens in healthy blood donors in southwest Iran. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 03000605211058870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaseth, M.; Mishra, G.; Jha, S.; Pandey, M.; Yadav, G.; Sah, G. Relation between ABO blood group and Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with peptic ulcer disease at Provincial Hospital: A cross sectional study. MedS Alliance J. Med. Med. Sci. 2021, 1, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajlouni, K.; Batieha, A.; Jaddou, H.; Khader, Y.; Abdo, N.; El-Khateeb, M.; Hyassat, D.; Al-Louzi, D. Time trends in diabetes mellitus in Jordan between 1994 and 2017. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaridah, N.; Joudeh, R.M.; Raba’a, F.J.; AlRefaei, A.; Shewaikani, N.; Nassr, H.; Jum’ah, M.; Aljarawen, M.; Al-Abdallat, H.; Haj-Ahmad, L.M. Attitudes and Practices Regarding Helicobacter Pylori Infection Among the Public in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Cureus 2024, 16, e55018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abegaz, S.B. Human ABO blood groups and their associations with different diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6629060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.M.; Al-Fishawy, H.S.; Shaltout, I.; Elnaeem, E.A.A.; Mohamed, A.S.; Salem, A.E. A comparative study between current and past Helicobacter pylori infection in terms of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almorish, M.A.; Al-Absi, B.; Elkhalifa, A.M.; Elamin, E.; Elderdery, A.Y.; Alhamidi, A.H. ABO, Lewis blood group systems and secretory status with H. pylori infection in yemeni dyspeptic patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedmat, H.; Karbasi-Afshar, R.; Agah, S.; Taheri, S. Helicobacter pylori Infection in the general population: A Middle Eastern perspective. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 4, 745. [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghian, A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among the healthy population in Iran and countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 17618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, I.E. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaid, J.M.; Ayoon, A.N.; Almurisy, O.N.; Alshuaibi, S.M.; Alkhawlani, N.N. Evaluation of antibody immunochromatography testing for diagnosis of current Helicobacter pylori infection. Pract. Lab. Med. 2021, 26, e00245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalek, S.; Hamed, W.; Nagy, N.; Shokry, K.; Abdelrahman, H. Evaluation of the diagnostic performance and the utility of Helicobacter pylori stool antigen lateral immunochromatography assay. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-Y.; Wei, J.-N.; Kuo, C.-H.; Liou, J.-M.; Lin, M.-S.; Shih, S.-R.; Hua, C.-H.; Hsein, Y.-C.; Hsu, Y.-W.; Chuang, L.-M. The impact of gastric atrophy on the incidence of diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawro, N.; Amann, U.; Butt, J.; Meisinger, C.; Akmatov, M.K.; Pessler, F.; Peters, A.; Rathmann, W.; Kääb, S.; Waterboer, T. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity: Prevalence, associations, and the impact on incident metabolic diseases/risk factors in the population-based KORA study. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Song, L.; Hu, L.; Hu, M.; Lei, X.; Huang, Y.; Lv, Y. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with diabetes among Chinese adults. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Fang, W.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Kao, T.-W.; Chang, Y.-W.; Wu, C.-J.; Zhou, Y.-C.; Sun, Y.-S.; Chen, W.-L. Helicobacter pylori infection increases risk of incident metabolic syndrome and diabetes: A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0208913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Yang, K.; Yuan, J.; Yao, P.; Wei, S. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with type 2 diabetes among a middle-and old-age Chinese population. Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 2016, 32, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ma, H. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and glycated hemoglobin A in diabetes: A meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 3705264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haj, S.; Chodick, G.; Refaeli, R.; Goren, S.; Shalev, V.; Muhsen, K. Associations of Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic disease with diabetic mellitus: Results from a large population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.E. Epidemiology, pathogenicity, risk factors, and management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Saudi Arabia. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 24, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, M.; Elshamsy, M.; Wasim, H.; Shedid, M.; Boraik, A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in delta Egypt. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 154, S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.-K.; Hong, Y.-K.; Hu, S.-W.; Fan, H.-C.; Ting, W.-H. A significant association between type 1 diabetes and helicobacter pylori infection: A meta-analysis study. Medicina 2024, 60, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, G.B.; Menon, M.; Gizaw, S.T.; Yimenu, B.W.; Agidew, M.M. Evaluation of lipid profile and inflammatory marker in patients with gastric Helicobacter pylori infection, Ethiopia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, H.; Morshedzadeh, N.; Naghashian, F. Signaling pathways linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2017, 11, S307–S309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Feng, T.; Su, L.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.; Ma, X. Interactions between Helicobacter pylori infection and host metabolic homeostasis: A comprehensive review. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansori, K.; Dehghanbanadaki, H.; Naderpour, S.; Rashti, R.; Moghaddam, A.B.; Moradi, Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodoushan, S.A.H.; Nabavi, A. The interaction of Helicobacter pylori infection and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Yang, Z.; Lu, N.-H. Helicobacter pylori infection and diabetes: Is it a myth or fact? World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R.; Winter, J.A.; Robinson, K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: Etiology and clinical outcomes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 8, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalamandris, S.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Papamikroulis, G.-A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Papaioannou, S.; Deftereos, S.; Tousoulis, D. The role of inflammation in diabetes: Current concepts and future perspectives. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangvarasittichai, S.; Pongthaisong, S.; Tangvarasittichai, O. Tumor necrosis factor-A, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein levels and insulin resistance associated with type 2 diabetes in abdominal obesity women. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2016, 31, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, O.S.; Mitra, R.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Kar, S.; Mukherjee, O. Is diabetes Mellitus a Predisposing factor for Helicobacter pylori infections? Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2023, 23, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.; Dunning, T.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L. Diabetes in older people: New insights and remaining challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordström, A.; Hadrévi, J.; Olsson, T.; Franks, P.W.; Nordström, P. Higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes in men than in women is associated with differences in visceral fat mass. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3740–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, L.G.; Jensen, B.W.; Ängquist, L.; Osler, M.; Sørensen, T.I.; Baker, J.L. Change in overweight from childhood to early adulthood and risk of type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrani, Z.; Robinson, K.; Taye, B. Association between ABO blood groups and Helicobacter pylori infection: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, Y.; Mekonen, W.; Birhanu, Y.; Sisay, T. The association between ABO blood group distribution and peptic ulcer disease: A cross-sectional study from Ethiopia. J. Blood Med. 2019, 10, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mattos, C.C.B.; de Mattos, L.C. Histo-blood group carbohydrates as facilitators for infection by Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 53, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Yamaoka, Y. Helicobacter pylori BabA in adaptation for gastric colonization. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooling, L. Blood groups in infection and host susceptibility. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 801–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, K.; Gharibi, Z.; Davoodian, P.; Gouklani, H.; Hassaniazad, M.; Ahmadi, N. The effect of smoking on the increase of infectious diseases. Tob. Health 2022, 1, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Morais, S.; Pelucchi, C.; Aragonés, N.; Kogevinas, M.; López-Carrillo, L.; Malekzadeh, R.; Tsugane, S.; Hamada, G.S.; Hidaka, A. Smoking and Helicobacter pylori infection: An individual participant pooled analysis (Stomach Cancer Pooling-StoP Project). Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 28, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsopoulou, S.; Satsangi, J.; Campbell, B.J.; Probert, C.S. impact of cigarette smoking on intestinal inflammation—Direct and indirect mechanisms. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 1268–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Chen, Q.; Xie, M. Smoking increases the risk of infectious diseases: A narrative review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, N.L.; Rose, T.C.; Hawker, J.; Violato, M.; O’Brien, S.J.; Barr, B.; Howard, V.J.; Whitehead, M.; Harris, R.; Taylor-Robinson, D.C. Relationship between socioeconomic status and gastrointestinal infections in developed countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, O.; Fernandes, I.; Veiga, N.; Pereira, C.; Chaves, C.; Nelas, P.; Silva, D. Living conditions and Helicobacter pylori in adults. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9082716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonaitis, P.; Nyssen, O.P.; Saracino, I.M.; Fiorini, G.; Vaira, D.; Pérez-Aísa, Á.; Tepes, B.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Pabón-Carrasco, M.; Keco-Huerga, A. Comparison of the management of Helicobacter pylori infection between the older and younger European populations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, A.; Dehghanbanadaki, H.; Naderpour, S.; Pirkashani, L.M.; Rajabi, A.; Rashti, R.; Riahifar, S.; Moradi, Y. The association between Helicobacter pylori and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case–control studies. Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diabetics (n = 149) | Non-Diabetics (n = 168) | Chi-Square Test | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 92 (61.7%) | 87 (51.8%) | χ2 = 2.79 | p = 0.09 |

| Female | 57 (38.3%) | 81 (48.2%) | ||

| Age Mean (SD) | 57.8 (12.8) | 43.1 (13.4) | p ≤ 0.05 | |

| 20–29 | 3 (2.0%) | 34 (20.2%) | χ2 = 78.73 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 30–39 | 10 (6.7%) | 26 (15.4%) | ||

| 40–49 | 22 (15.4%) | 56 (33.3%) | ||

| 50–59 | 39 (26.2%) | 28 (16.7%) | ||

| 60–69 | 52 (34.9%) | 22 (13.1%) | ||

| 70–79 | 16 (10.7%) | 2 (1.2%) | ||

| 80+ | 6 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| BMI Mean (SD) | 30.77 (5.85) | 28.45 (5.36) | t = 3.19 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| <18.5 | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (2.4%) | χ2 = 7.61 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 22 (14.7%) | 36 (21.4%) | ||

| 25–29.9 | 56 (37.6%) | 72 (42.9%) | ||

| 30–34.9 | 43 (28.8%) | 39 (23.2%) | ||

| 35–39.9 | 23 (15.4%) | 16 (9.5%) | ||

| 40+ | 3 (2.0%) | 1 (2.4%) | ||

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Smoker | 70 (47.0%) | 60 (35.7%) | χ2 = 4.19 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Non-Smoker | 79 (53.0%) | 108 (64.3%) | ||

| Education level | ||||

| Illiterate | 11 (7.4%) | 2 (1.2%) | (χ2) = 42.92 | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Primary | 30 (20.1%) | 16 (9.5%) | ||

| Secondary | 49 (32.9%) | 83 (49.4%) | ||

| Bachelor’s | 46 (30.9%) | 66 (39.3%) | ||

| Postgraduate | 13 (8.7%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Diabetics | Non-Diabetics | OR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 92 | 87 | 1.5 (95% CI: 0.60–1.72) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Female | 57 | 81 | 0.66 | |

| Age | ||||

| 20–29 | 3 | 34 | 0.096 (95% CI: 0.03–0.32) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 30–39 | 10 | 26 | 0.38 (95% CI: 0.19–0.79) | p = 0.02 |

| 40–49 | 23 | 56 | 0.45 (95% CI: 0.27–0.74) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 50–59 | 39 | 28 | 0.73 95% CI: 0.41–1.29) | p = 0.14 |

| 60–69 | 52 | 22 | 2.80 (95% CI: 1.69–4.66) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 70–79 | 16 | 2 | 9.25 (95% CI: 2.12–40.35) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| 80+ | 6 | 0 | 14.1 (95% CI: 2.78–54.5) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| BMI | ||||

| <18.5 | 2 | 4 | 0.56 (95% CI: 0.10–3.09) | p = 0.69 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 22 | 36 | 0.64 (95% CI: 0.35–1.14) | p = 0.15 |

| 25–29.9 | 56 | 72 | 0.80 (95% CI: 0.51–1.26) | p = 0.36 |

| 30–34.9 | 43 | 39 | 1.34 (95% CI: 0.81–2.22) | p = 0.30 |

| 35–39.9 | 23 | 16 | 1.73 (95% CI: 0.88–3.42) | p = 0.12 |

| 40+ | 3 | 1 | 3.43 (95% CI: 0.35–33.35) | p = 0.35 |

| Tabaco use | ||||

| Smoker | 70 | 60 | 1.60 (95% CI: 1.02–2.50) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Non-Smoker | 79 | 108 | 0.62 (95% CI: 0.40–0.98) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Education level | ||||

| Illiterate | 11 | 2 | 6.62 (95% CI: 1.44–30.35) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Primary | 30 | 16 | 2.39 (95% CI: 1.25–4.60) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Secondary | 49 | 83 | 0.50 (95% CI: 0.32–0.97) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Bachelor’s | 46 | 66 | 0.69 (95% CI: 0.43–1.10) | p = 0.13 |

| Postgraduate | 13 | 1 | 15.96 (95% CI: 2.06–123.57) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Diabetics (n = 149) | Non-Diabetics (n = 168) | Logistic Regression p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p Value | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 92 | 87 | 1.22 (95% CI: 0.89–1.66) | p = 0.44 |

| Female | 57 | 81 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 20–29 | 0.11 (0.03–0.36) | p ≤ 0.05 | ||

| 30–39 | 0.29 (0.13–0.60) | p ≤ 0.05 | ||

| 40–49 | 0.39 (0.23–0.66) | p ≤ 0.05 | ||

| 50–59 | 0.71 (0.44–1.12) | p = 0.14 | ||

| ≥60 (reference) | ||||

| BMI | ||||

| <25 kg/m2 (reference) | ||||

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 1.32 (0.86–2.02 | p = 0.2 | ||

| 30–34.9 kg/m2 | 1.89 (1.12–3.18) | p ≤ 0.05 | ||

| ≥35 kg/m2 | 2.42 (1.21–4.86) | p ≤ 0.05 | ||

| Tabaco use | ||||

| Smoker | 70 | 60 | 1.51 (95% CI: 1.03–2.23) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| Non-Smoker | 79 | 108 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| School or less | 90 | 101 | 2.28 (95% CI: 1.28–4.02) | p ≤ 0.05 |

| University | 59 | 67 | ||

| Variable | Diabetics (n) | Non-Diabetics (n) | OR (95% CI)/p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 60 y | 68 | 24 | 3.12 (1.85–5.27); p ≤ 0.05 |

| Smoker | 70 | 60 | 1.60 (1.02–2.50); p ≤ 0.05 |

| Education ≤ Secondary | 90 | 101 | 1.56 (1.28–2.44); p ≤ 0.05 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 69 | 56 | 1.34 (0.81–2.22); p = 0.30 |

| Type 2 Diabetics (n = 149) | Non-Diabetics (n = 168) | Chi-Square | df | p Value | OR | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive for H. pylori (n = 89) | 51 (34.2%) | 38 (22.6%) | 4.711 | 1 | ≤0.05 | 1.78 (1.08–2.92) | p = 0.122 |

| Negative for H. pylori (n = 228) | 98 (65.7%) | 130 (77.6%) |

| Subcategory | H. pylori_Pos (n = 89) | H. pylori_Neg (n = 228) | Chi-Square | df | p Value | Cramer’s Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 21 (23.6%) | 89 (37.7%) | 15.01 | 3 | <0.001 | 0.218, small-to-moderate association |

| B | 13 (14.6%) | 46 (18.4%) | ||||

| AB | 11 (12.6%) | 31 (12.3%) | ||||

| O | 44 (49.4%) | 62 (26.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Momani, H.; Bani-Hani, A.; Jaber, A.A.; Alsmady, A.; Sobh, Y.; Otoom, B.; Aolymat, I.; Khasawneh, A.I.; Tabl, H.; Alsheikh, A.; et al. The Prevalence of H. pylori Among Jordanian Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Its Association with ABO Blood Group. Medicina 2025, 61, 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122167

Al-Momani H, Bani-Hani A, Jaber AA, Alsmady A, Sobh Y, Otoom B, Aolymat I, Khasawneh AI, Tabl H, Alsheikh A, et al. The Prevalence of H. pylori Among Jordanian Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Its Association with ABO Blood Group. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122167

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Momani, Hafez, Amro Bani-Hani, Ahmad A. Jaber, Azhar Alsmady, Yusra Sobh, Bassam Otoom, Iman Aolymat, Ashraf I. Khasawneh, Hala Tabl, Ayman Alsheikh, and et al. 2025. "The Prevalence of H. pylori Among Jordanian Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Its Association with ABO Blood Group" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122167

APA StyleAl-Momani, H., Bani-Hani, A., Jaber, A. A., Alsmady, A., Sobh, Y., Otoom, B., Aolymat, I., Khasawneh, A. I., Tabl, H., Alsheikh, A., Zueter, A. M., & Al-Shudifat, A.-E. (2025). The Prevalence of H. pylori Among Jordanian Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Its Association with ABO Blood Group. Medicina, 61(12), 2167. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122167