Lymphocyte Subtypes in Local Inflammatory Response: A Comparative Analysis of Simple and Complicated Appendicitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Samples

2.2. Tissue Sections, Monoclonal Antibodies, and Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

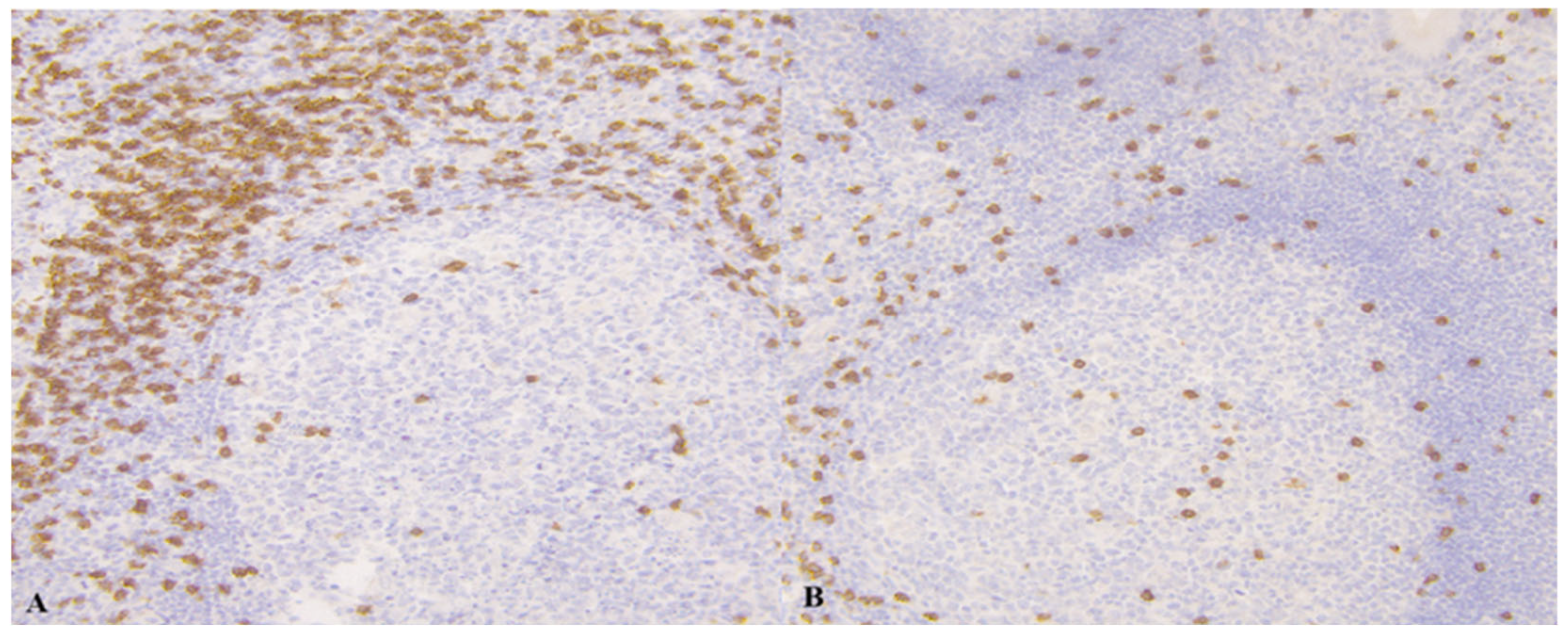

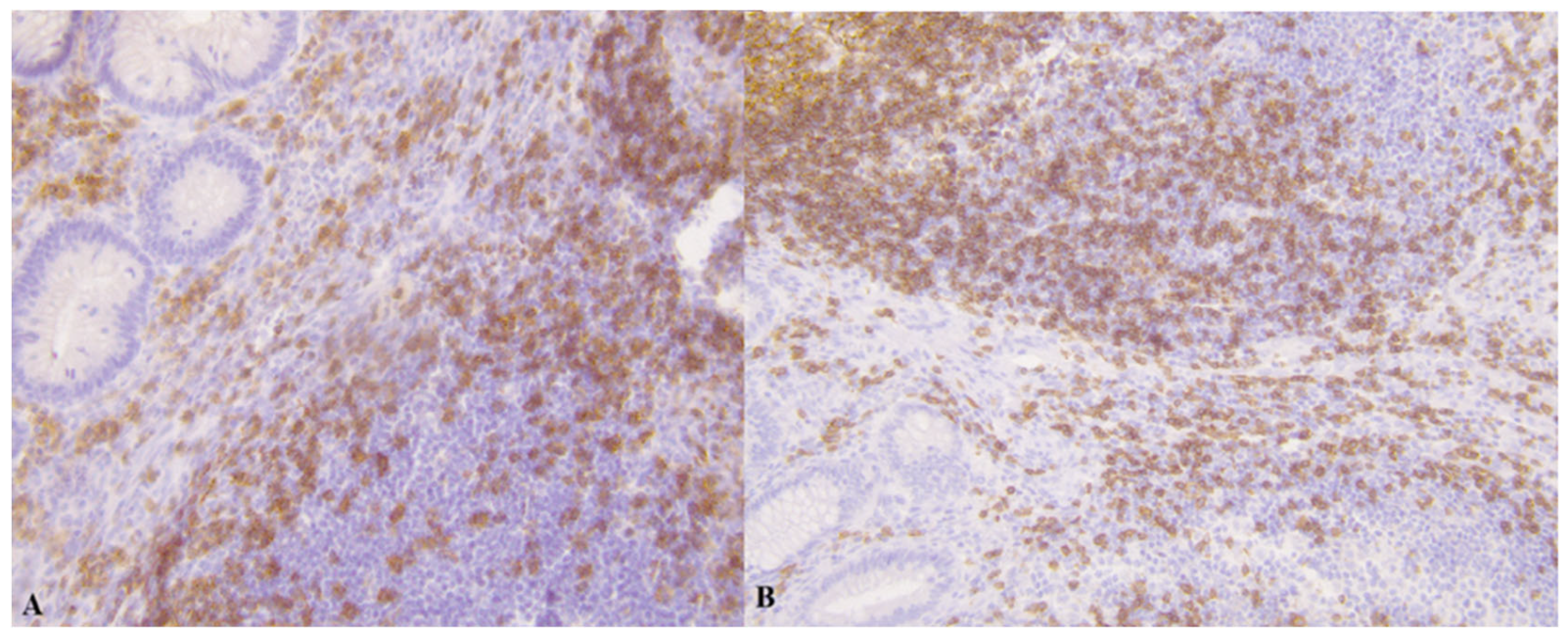

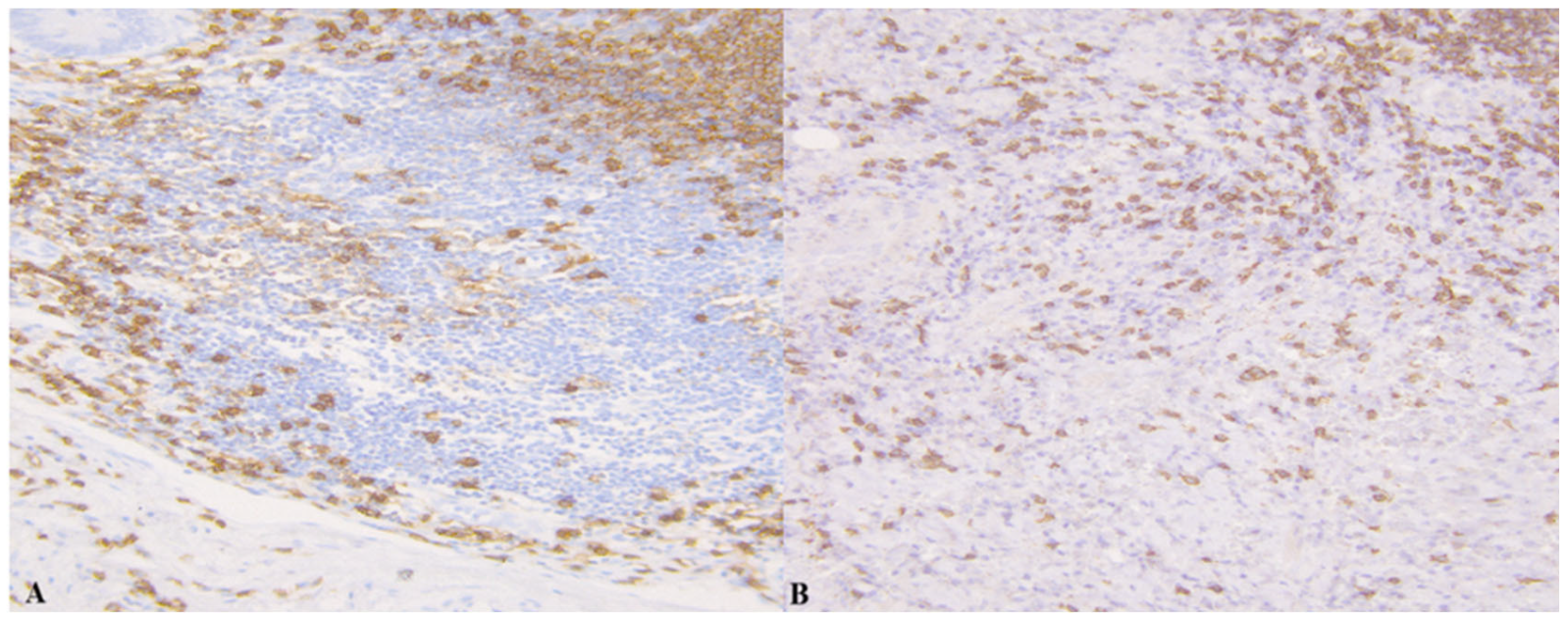

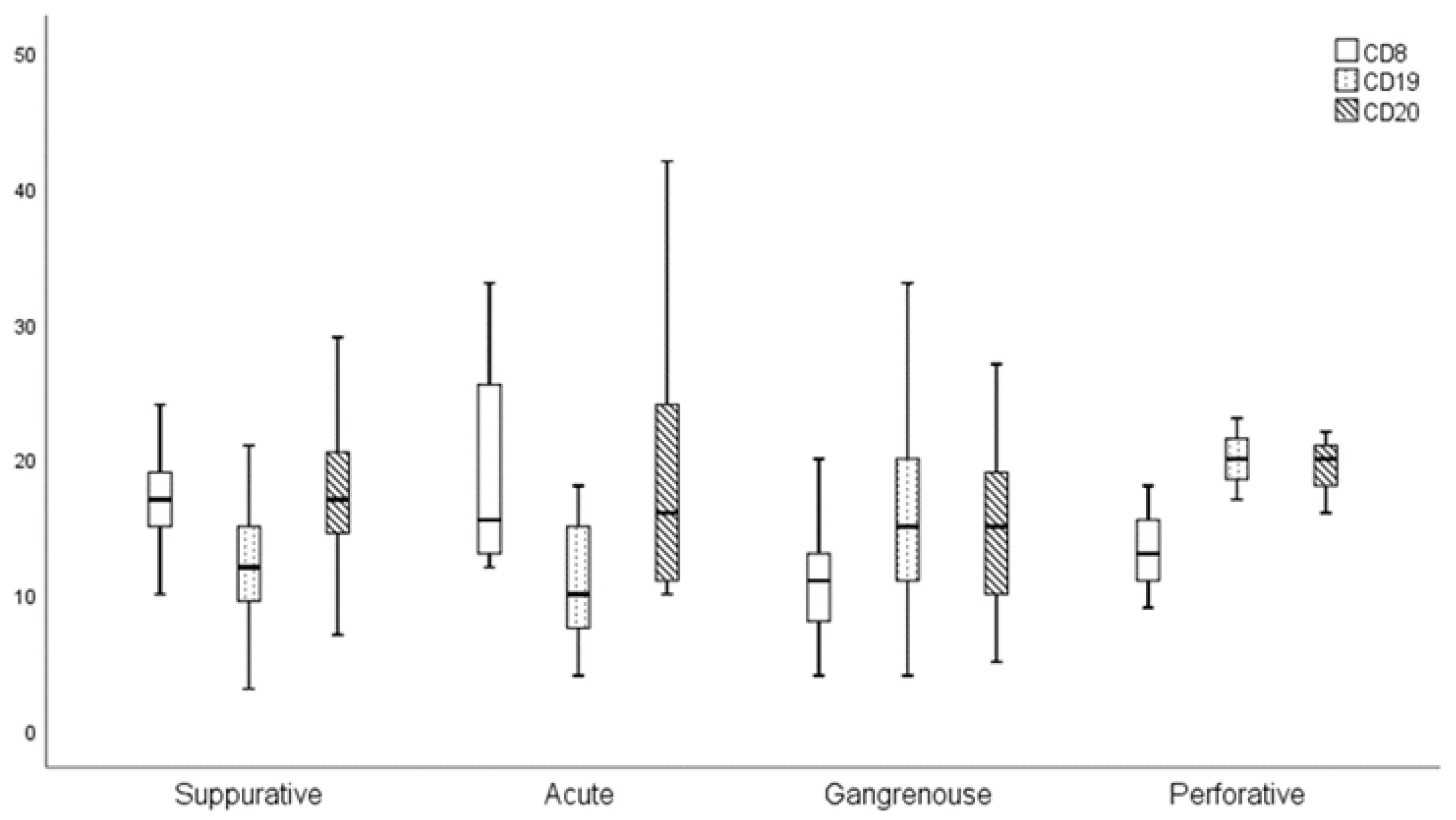

3.1. Results of Immunohistochemistry

3.2. Results of Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WBCC | white blood cell count per μL of blood |

| ANC | absolute neutrophil count |

| ALC | absolute lymphocyte count |

| AMC | absolute monocyte count |

| ANC/ALC | neutrophil–to–lymphocyte ratio |

| ANC/AMC | neutrophil–to–monocyte ratio |

| CRP–C | reactive protein |

References

- Tayebi, A.; Olamaeian, F.; Mostafavi, K.; Khosravi, K.; Tizmaghz, A.; Bahardoust, M.; Zakaryaei, A.; Mehr, D.E. Assessment of Alvarado criteria, ultrasound, CRP, and their combination in patients with suspected acute appendicitis: A single centre study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, E.H.; Fomby, T.B.; Woodward, W.A.; Haley, R.W. Epidemiological similarities between appendicitis and diverticulitis suggesting a common underlying pathogenesis. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Krishnan, N.; Birley, J.R.; Tintor, G.; Bajpai, M.; Pogorelić, Z. Hyponatremia–A New Diagnostic Marker for Complicated Acute Appendicitis in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta–Analysis. Children 2022, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosayebi, G.; Alizadeh, S.A.; Alasti, A.; Nobaveh, A.A.; Ghazavi, A.; Okhovat, M.; Rafiei, M. Is CD19 an immunological diagnostic marker for acute appendicitis? Iran. J. Immunol. 2013, 10, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kooij, I.A.; Sahami, S.; Meijer, S.L.; Buskens, C.J.; Te Velde, A.A. The immunology of the vermiform appendix: A review of the literature. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016, 186, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minneci, P.C.; Hade, E.M.; Lawrence, A.E.; Sebastião, Y.V.; Saito, J.M.; Mak, G.Z.; Fox, C.; Hirschl, R.B.; Gadepalli, S.; Helmrath, M.A.; et al. Association of Nonoperative Management Using Antibiotic Therapy vs Laparoscopic Appendectomy With Treatment Success and Disability Days in Children With Uncomplicated Appendicitis. JAMA 2020, 324, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Banever, G.T.; Karrer, F.M.; Partrick, D.A. Appendicitis in children less than 5 years old: Influence of age on presentation and outcome. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 204, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaiq, M.; Niaz–Ud–Din Jalil, A.; Zubair, M.; Shah, S.A. Diagnostic accuracy of leukocytosis in prediction of acute appendicitis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2014, 24, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Subhas, G.; Mittal, V.K.; Golladay, E.S. C-reactive protein estimation does not improve accuracy in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in pediatric patients. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 7, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez–Sanjuán, J.C.; Martín–Parra, J.I.; Seco, I.; García–Castrillo, L.; Naranjo, A. C-reactive protein and leukocyte count in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Dis. Colon Rectum 1999, 42, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Parash, T.H.; Banu, L.A. Diameter of the lymphoid follicles in the vermiform appendix of Bangladeshi cadaver. Mymensingh Med. J. 2014, 23, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gramlich, T.L.; Petras, R.E. Vermiform Appendix. In Histology for Pathologists, 3rd ed.; Mills, S.E., Ed.; Lippincott Williams &Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 589–602. [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, R.R.; Wassenaar, E.C.E.; de Boer, O.J.; Bakx, R.; Roelofs, J.J.; Bunders, M.J.; van Heurn, L.E.; Heij, H.A. Composition of the cellular infiltrate in patients with simple and complex appendicitis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 214, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, M.; Puri, P.; Reen, D.J. Characterisation of the local inflammatory response in appendicitis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1993, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devadiga, S.; McElroy, A.K.; Prabhu, S.G.; Arunkumar, G. Dynamics of human B and T cell adaptive immune responses to Kyasanur Forest disease virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.B.; Li, X.W.; Hou, S.Y.; Chi, X.-Q.; Shan, H.-F.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Li, X.-B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, T.-J. Preoperatively predicting the pathological types of acute appendicitis using machine learning based on peripheral blood biomarkers and clinical features: A retrospective study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuga, T.; Taniguchi, S.; Inoue, T.; Zempo, N.; Esato, K. Immunocytochemical analysis of cellular infiltrates in human appendicitis. Surg. Today 2000, 30, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroubakis, I.E.; Vlachonikolis, I.G.; Kouroumalis, E.A. Role of appendicitis and appendectomy in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis: A critical review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2002, 8, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somekh, E.; Serour, F.; Gorenstein, A.; Vohl, M.; Lehman, D. Phenotypic pattern of B cells in the appendix: Reduced intensity of CD19 expression. Immunobiology 2000, 201, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyun, L.; Kurchenko, I.; Bisyuk, Y. Immunohistochemical analysis of appendix cell wall infiltrate in acute phlegmonouse appendicitis. Georgian Med. News 2017, 270, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Makama, J.G.; Kache, S.A.; Ajah, L.J.; Ameh, E.A. Intestinal obstruction caused by appendicitis:A systematic review. J. West Afr. Coll. Surg. 2017, 7, 94–115. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.U.; Iqbal, A.; Habib, M.; Nisar, M.U.; Ayub, A.; Chaudhary, M.A.; Babar, S. Hyponatremia As A Marker Of Complicated Appendicitis. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2022, 34 (Suppl. S1), S974–S978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Group | Group A | Group B | p 1a | p 1b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD 8% | 15.00 ± 4.60 | 16.83 ± 5.67 | 11.98 ± 5.65 | 0.417 | <0.001 |

| CD 19% | 12.65 ± 3.73 | 12.14 ± 5.53 | 16.24 ± 7.68 | 0.407 | 0.007 |

| CD 20% | 20.30 ± 9.76 | 17.37 ± 7.21 | 16.09 ± 7.88 | 0.073 | 0.186 |

| † | <7 Years | 8–13 Years | 14+ Years | p 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8% | 12.95 ± 4.57 | 14.28 ± 5.96 | 14.86 ± 7.66 | 0.875 |

| CD19% | 14.65 ± 8.83 | 15.08 ± 6.64 | 13.1 ± 6.16 | 0.544 |

| CD20% | 17.4 ± 10.23 | 15.74 ± 5.79 | 17.62 ± 7.77 | 0.683 |

| Parameter † | Control Group | Group A | Group B | p 1a | p1b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Le | 10.73 ± 5.71 | 17.86 ± 6.39 | 17.4 ± 5.44 | <0.001 | 0.957 |

| Ne% | 59.16 ± 19.2 | 77.51 ± 8.13 | 78.89 ± 7.94 | <0.001 | 0.426 |

| Ne (count) | 6.79 ± 5.05 | 16.05 ± 12.2 | 13.47 ± 5.06 | <0.001 | 0.594 |

| Ly% | 29.89 ± 17.16 | 13.57 ± 6.74 | 12.71 ± 6.71 | <0.001 | 0.541 |

| Ly (count) | 2.73 ± 1.8 | 2.19 ± 0.94 | 2.1 ± 1.13 | 0.236 | 0.447 |

| Ne/Ly | 3.99 ± 5.61 | 8.98 ± 8.33 | 8.5 ± 6.2 | <0.001 | 0.945 |

| Mo% | 8.02 ± 3.79 | 6.38 ± 2.41 | 6.25 ± 2.64 | 0.061 | 0.828 |

| Mo (count) | 0.92 ± 0.74 | 1.1 ± 0.47 | 1.08 ± 0.51 | 0.048 | 0.917 |

| Ne/Mo | 9.67 ± 6.77 | 15.7 ± 10.48 | 15.53 ± 11.54 | 0.001 | 0.775 |

| CRP | 21.94 ± 33.94 | 66.75 ± 78.6 | 103.93 ± 85.04 | <0.001 | 0.014 |

| Na | 128.53 ± 32.03 | 136.8 ± 2.65 | 135.97 ± 3.57 | 0.800 | 0.356 |

| Albumin | 38.38 ± 5.5 | 38.66 ± 4.2 | 38.83 ± 4.3 | 0.948 | 0.868 |

| Glycemia | 30.84 ± 105.19 | 5.48 ± 1.45 | 5.65 ± 1.39 | 0.575 | 0.246 |

| Total bilirubin | 31.22 ± 47.36 | 14.92 ± 12.67 | 17.43 ± 15.13 | 0.991 | 0.813 |

| Direct bilirubin | 3.23 ± 1.82 | 3.57 ± 2.18 | 7.67 ± 8.97 | 0.063 | 0.015 |

| Group A | Group B | ||||||||

| CD8 | CD19 | CD20 | NK ćelije | CD8 | CD19 | CD20 | NK ćelije | ||

| Le | r | −0.342 * | −0.078 | −0.138 | 0.101 | 0.286 | 0.215 | 0.091 | 0.055 |

| p | 0.044 | 0.654 | 0.428 | 0.564 | 0.057 | 0.157 | 0.553 | 0.721 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 44 | |

| Ne% | r | −0.150 | 0.154 | −0.111 | −0.044 | 0.129 | 0.152 | −0.032 | −0.065 |

| p | 0.389 | 0.376 | 0.527 | 0.803 | 0.398 | 0.319 | 0.837 | 0.677 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 44 | |

| Ne (count) | r | −0.292 | 0.072 | −0.075 | 0.132 | 0.342 * | 0.248 | 0.006 | 0.064 |

| p | 0.089 | 0.683 | 0.671 | 0.448 | 0.023 | 0.104 | 0.969 | 0.684 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Ly% | r | 0.260 | −0.072 | 0.087 | 0.026 | −0.091 | −0.114 | −0.033 | 0.174 |

| p | 0.132 | 0.679 | 0.621 | 0.884 | 0.557 | 0.463 | 0.832 | 0.265 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Ly (count) | r | 0.044 | −0.157 | 0.051 | −0.020 | 0.140 | −0.026 | −0.042 | 0.259 |

| p | 0.801 | 0.367 | 0.770 | 0.908 | 0.365 | 0.869 | 0.786 | 0.094 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Ne/Ly | r | −0.243 | 0.156 | −0.051 | 0.017 | 0.077 | 0.098 | −0.018 | −0.172 |

| p | 0.160 | 0.372 | 0.773 | 0.922 | 0.620 | 0.527 | 0.909 | 0.271 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Mo% | r | 0.012 | −0.209 | 0.316 | 0.059 | −0.090 | −0.159 | 0.036 | −0.265 |

| p | 0.947 | 0.229 | 0.064 | 0.737 | 0.563 | 0.303 | 0.817 | 0.085 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Mo (count) | r | −0.256 | −0.193 | 0.180 | 0.140 | 0.126 | 0.046 | 0.080 | −0.090 |

| p | 0.137 | 0.267 | 0.301 | 0.424 | 0.414 | 0.764 | 0.605 | 0.568 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| Ne/Mo | r | −0.085 | 0.319 | −0.185 | 0.002 | 0.093 | 0.189 | −0.040 | 0.214 |

| p | 0.626 | 0.062 | 0.286 | 0.992 | 0.548 | 0.220 | 0.798 | 0.169 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 43 | |

| CRP | r | −0.284 | −0.161 | 0.021 | 0.075 | 0.020 | −0.025 | −0.073 | −0.237 |

| p | 0.098 | 0.357 | 0.903 | 0.668 | 0.898 | 0.871 | 0.635 | 0.122 | |

| N | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 44 | |

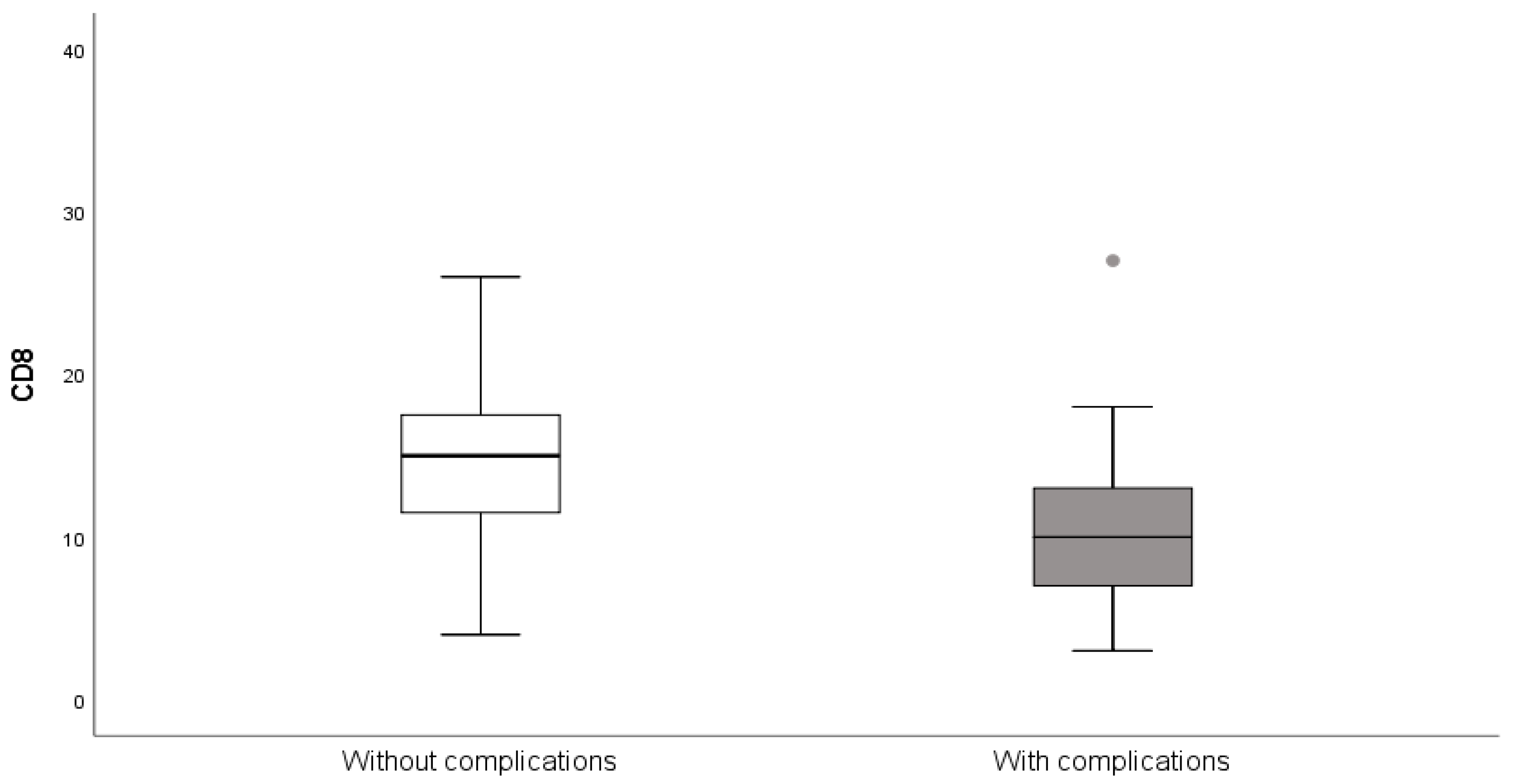

| † | Complications | Without Complications | p 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8% | 11.29 ± 6.16 | 14.86 ± 5.93 | 0.024 |

| CD19% | 16.06 ± 8.03 | 14.02 ± 6.82 | 0.403 |

| CD20% | 16.06 ± 10.68 | 16.81 ± 6.6 | 0.437 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zecevic, M.; Zivanovic, D.; Zivkovic, N.; Velickov, A.; Marjanovic, V.; Marjanovic, Z.; Milenkovic, S.; Sretenovic, A. Lymphocyte Subtypes in Local Inflammatory Response: A Comparative Analysis of Simple and Complicated Appendicitis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122161

Zecevic M, Zivanovic D, Zivkovic N, Velickov A, Marjanovic V, Marjanovic Z, Milenkovic S, Sretenovic A. Lymphocyte Subtypes in Local Inflammatory Response: A Comparative Analysis of Simple and Complicated Appendicitis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122161

Chicago/Turabian StyleZecevic, Maja, Dragoljub Zivanovic, Nikola Zivkovic, Aleksandra Velickov, Vesna Marjanovic, Zoran Marjanovic, Sanja Milenkovic, and Aleksandar Sretenovic. 2025. "Lymphocyte Subtypes in Local Inflammatory Response: A Comparative Analysis of Simple and Complicated Appendicitis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122161

APA StyleZecevic, M., Zivanovic, D., Zivkovic, N., Velickov, A., Marjanovic, V., Marjanovic, Z., Milenkovic, S., & Sretenovic, A. (2025). Lymphocyte Subtypes in Local Inflammatory Response: A Comparative Analysis of Simple and Complicated Appendicitis. Medicina, 61(12), 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122161