Oral Probiotics in Acne vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Clinical Significance of Acne

1.2. Recent Updates in Treatment Strategies

1.3. Prevalence of Acne vulgaris Compared with Other Acne Subtypes

1.4. Rationale for Microbiome-Directed Therapies

1.5. Limitations of Conventional Therapy

1.6. Evidence Landscape for Probiotics in Acne

1.7. Methodological Advances and Study Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and PRISMA Compliance

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Effect Measures

2.8. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

2.9. Reporting Bias Assessment

2.10. Certainty of Evidence

3. Results

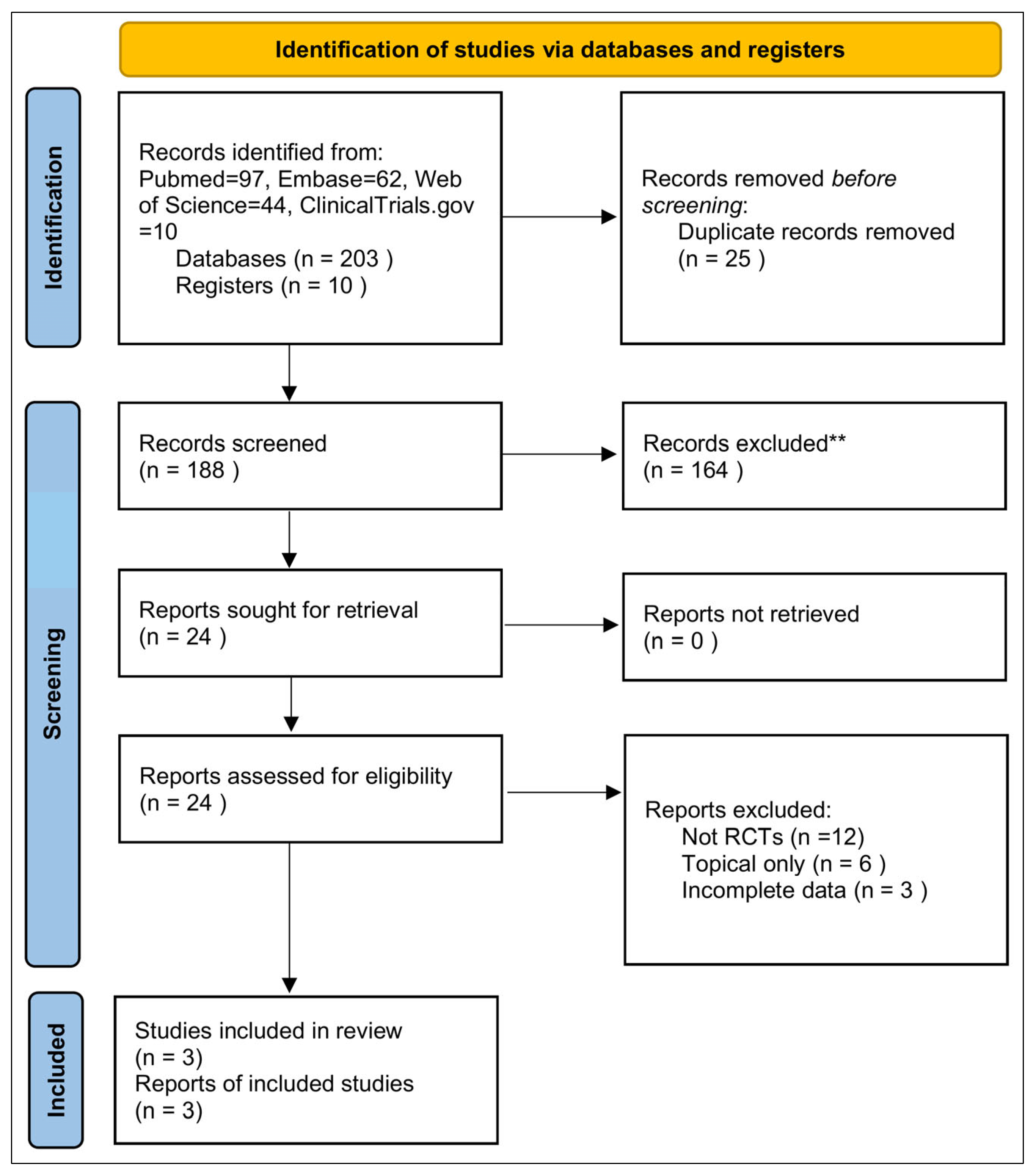

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

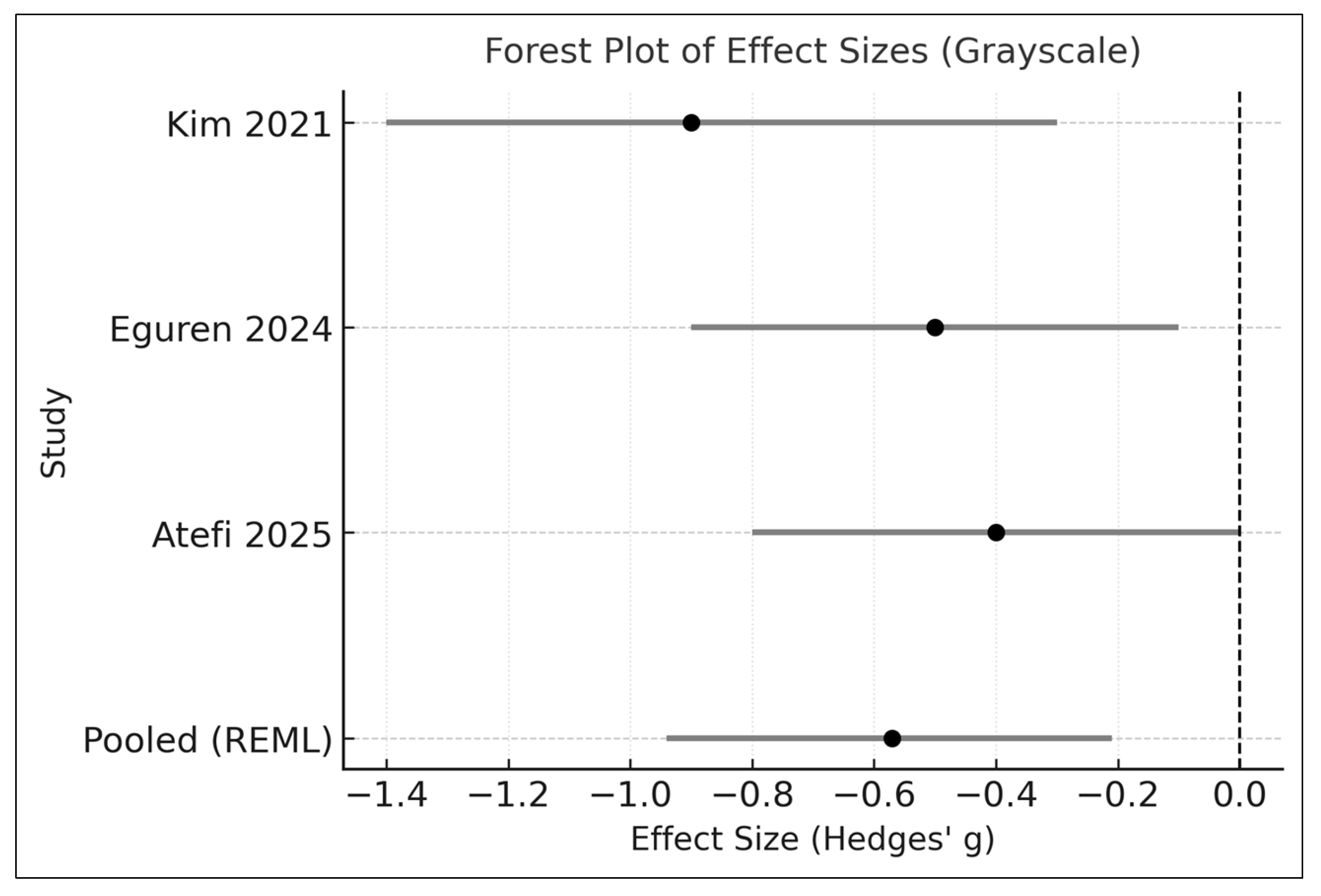

3.4. Effects on Acne Severity (Primary Outcome)

3.5. Sensitivity and Additional Analyses

3.5.1. DerSimonian–Laird Comparison

3.5.2. Leave-One-Out (LOO) Influence Analysis

3.5.3. Cumulative Meta-Analysis

3.5.4. Subgroup Exploration (Descriptive Only)

- (1)

- Multi-strain vs. single-strain formulations

- (2)

- Monotherapy vs. adjunctive therapy

- (3)

- Geographic region

- (4)

- Interpretation Summary

3.6. Publication Bias Assessment

3.7. Adverse Events

3.8. Certainty of Evidence

3.9. Safety and Tolerability

3.10. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation in Context of Existing Evidence (PRISMA 23a)

4.2. Limitations of Included Evidence (PRISMA 23b)

4.3. Influence of Study Design Differences on Inconsistency

4.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis Explanation

4.3.2. Subgroup Analysis Rationale (Severity, Duration, Dosage)

4.4. Limitations of the Review Process (PRISMA 23c)

4.5. Implications for Clinical Practice, Policy, and Research

4.6. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

Appendix A

| Item # | Checklist Item | Completed? | Location in Manuscript |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify as systematic review | Yes | Title Page/Abstract |

| 2 | Structured abstract | Yes | Abstract |

| 3 | Rationale | Yes | Introduction |

| 4 | Objectives | Yes | Introduction (final paragraph) |

| 5 | Eligibility criteria | Yes | Methods 2.2 |

| 6 | Information sources | Yes | Methods 2.3 |

| 7 | Search strategy | Yes | Appendix C |

| 8 | Selection process | Yes | Methods 2.4 |

| 9 | Data collection process | Yes | Methods 2.5 |

| 10 | Outcomes definition | Yes | Methods 2.7 |

| 11 | Risk of bias methods | Yes | Methods 2.6 |

| 12 | Effect measures | Yes | Methods 2.7 |

| 13 | Synthesis methods | Yes | Methods 2.8 |

| 14 | Reporting bias assessment | Yes | Methods 2.9 |

| 15 | Certainty assessment | Yes | Methods 2.10 |

| 16 | Study selection results | Yes | Results 3.1 + Figure 1 |

| 17 | Study characteristics | Yes | Results 3.2 + Table 3 |

| 18 | Risk of bias results | Yes | Results 3.3 + Table 1 |

| 19 | Results of individual studies | Yes | Results 3.4 + Figure 2 |

| 20 | Results of syntheses | Yes | Results 3.4–3.5 |

| 21 | Reporting bias results | Yes | Results 3.6 + Figure 3 |

| 22 | Certainty of evidence | Yes | Results 3.8 |

| 23 | Discussion of results | Yes | Discussion Section 4 |

| 24 | Limitations of evidence | Yes | Discussion 4.2 |

| 25 | Limitations of review processes | Yes | Discussion 4.3 |

| 26 | Implications for practice | Yes | Discussion 4.4 |

| 27 | Registration & protocol | Yes | Methods 2.1 (PROSPERO) |

Appendix B

| Item # | Checklist Item | Completed? | Where Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identification as a systematic review | Yes | Abstract—Opening sentence |

| 2 | Objectives | Yes | Abstract—Background and Objectives |

| 3 | Eligibility criteria | Yes | Abstract—Methods |

| 4 | Information sources and last search date | Yes | Abstract—Methods |

| 5 | Risk of bias assessment | Yes | Abstract—Methods |

| 6 | Synthesis methods | Yes | Abstract—Methods |

| 7 | Included studies and participants | Yes | Abstract—Results |

| 8 | Effect of intervention | Yes | Abstract—Results |

| 9 | Limitations of evidence | Yes | Abstract—Conclusions |

| 10 | Interpretation | Yes | Abstract—Conclusions |

| 11 | Funding | Yes | Abstract—Funding statement |

| 12 | Registration | Yes | Abstract—Registration line (PROSPERO) |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

Appendix C.1.1. PubMed Search Strategy (Last Updated: November 2025)

Appendix C.1.2. Embase (Elsevier) Search Strategy

Appendix C.1.3. Web of Science Core Collection

Appendix C.1.4. ClinicalTrials.gov Search Strategy

Appendix C.1.5. Additional Search Procedures

Appendix C.2. Summary Statement

References

- Nast, A.; Dréno, B.; Bettoli, V.; Mokos, Z.B.; Degitz, K.; Dressler, C.; Finlay, A.; Haedersdal, M.; Lambert, J.; Layton, A.; et al. European evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of acne-update 2016-short version. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Eady, A.; Philpott, M.; Goldsmith, L.A.; Orfanos, C.; Cunliffe, W.C.; Rosenfield, R. What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp. Dermatol. 2005, 14, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Navarro-Moratalla, L.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Ruzafa-Costas, B.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-López, V. Acne, Microbiome, and Probiotics: The Gut-Skin Axis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhate, K.; Williams, H.C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, A.H.S.; Chew, F.T. Systematic review of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lynn, D.D.; Umari, T.; Dunnick, C.A.; Dellavalle, R.P. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2016, 7, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reynolds, R.V.; Yeung, H.; Cheng, C.E.; Cook-Bolden, F.; Desai, S.R.; Druby, K.M.; Freeman, E.E.; Keri, J.E.; Gold, L.F.S.; Tan, J.K.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1006.e1–1006.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, J.Y.; Smith, L.L. Psychologic aspects of acne. Pediatr. Dermatol. 1991, 8, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorsen, J.A.; Stern, R.S.; Dalgard, F.; Thoresen, M.; Bjertness, E.; Lien, L. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: A population-based study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, A.M.; Thiboutot, D.; Tan, J. Reviewing the global burden of acne: How could we improve care to reduce the burden? Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognia, J.L.; Schaffer, J.V.; Cerroni, L. (Eds.) Dermatology, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Plewig, G.; Melnik, B.; Chen, W.C. (Eds.) Plewig and Kligman’s Acne and Rosacea, 4th ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, O.H., Jr.; Kligman, A. Acne mechanica. Arch. Dermatol. 1975, 111, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, K.D. Chloracne. Br. J. Dermatol. 1970, 83, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, R.M. Steroid acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1989, 21, 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du-Thanh, A.; Kluger, N.; Bensalleh, H.; Guillot, B. Drug-induced acneiform eruption. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2011, 12, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Aidy, S.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut Microbiota: The Conductor in the Orchestra of Immune-Neuroendocrine Communication. Clin. Ther. 2015, 37, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, A.; Mozafarpoor, S.; Bodaghabadi, M.; Mohamadi, M. The Potential Role of Probiotics in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Literature Review on Acne and Microbiota. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, H. Acne, the Skin Microbiome, and Antibiotic Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.; Schmidt, T.S.; Bengs, S.; Poveda, L.; Opitz, L.; Atrott, K.; Stanzel, C.; Biedermann, L.; Rehman, A.; Jonas, D.; et al. Effects of oral antibiotics and isotretinoin on murine gut microbiota. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiboutot, D.M.; Dréno, B.; Abanmi, A.; Alexis, A.F.; Araviiskaia, E.; Cabal, M.I.B.; Bettoli, V.; Casintahan, F.; Chow, S.; da Costa, A.; et al. Practical management of acne for clinicians: International consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, S1–S23.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguren, C.; Navarro-Blasco, A.; Corral-Forteza, M.; Reolid-Pérez, A.; Setó-Torrent, N.; García-Navarro, A.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Navarro-López, V. A Randomized Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of an Oral Probiotic in Acne Vulgaris. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2024, 104, 33206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atefi, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Bodaghabadi, M.; Mehrali, M.; Behrangi, E.; Ghassemi, M.; Jafarzadeh, A.; Goodarzi, A. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Probiotic Supplementation in Combination With Doxycycline for Moderate Acne: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e16614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ko, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, N.I.; Ha, W.K.; Cho, Y. Lactobacillus plantarum CJLP55 attenuates acne symptoms and modulates gene expression in the skin: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, M.M.; Bowe, W.P. The effect of probiotics on immune regulation, acne, and photoaging. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2015, 1, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrocini, G.; Bertona, M.; Picazo, Ó.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Monfrecola, G.; Emanuele, E. Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 helps normalise skin gene expression related to insulin signalling and leads to improvements in adult acne. Benef. Microbes 2016, 7, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueniche, A.; Philippe, D.; Bastien, P.; Reuteler, G.; Blum, S.; Castiel-Higounenc, I.; Breton, L.; Benyacoub, J. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of Lactobacillus paracasei NCC 2461 on skin reactivity. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, D.; O’mAhony, L.; Murphy, E.F.; Bourke, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Kiely, B.; Shanahan, F.; Quigley, E.M. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 modulates host inflammatory processes beyond the gut. Gut Microbes 2013, 4, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dunaway, S.; Champer, J.; Kim, J.; Alikhan, A. Changing our microbiome: Probiotics in dermatology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, S.E.; Poutahidis, T. Probiotic ‘glow of health’: It’s more than skin deep. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between—Study variance and its uncertainty in meta—Analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J.; Knapp, G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 3875–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Langan, D.; Higgins, J.P.; Simmonds, M. Comparative performance of heterogeneity variance estimators in meta-analysis: A review of simulation studies. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 7.0 (updated 2025); Cochrane: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: An updated instrument for evaluating bias risk in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, N.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rücker, G.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottin, V.H.M.; Suyenaga, E.S. An approach on the potential use of probiotics in the treatment of skin conditions: Acne and atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutema, I.A.M.P.; Latarissa, I.R.; Widowati, I.G.A.R.; Sartika, C.R.; Ciptasari, N.W.E.; Lestari, K. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplements and Topical Applications in the Treatment of Acne: A Scoping Review of Current Results. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Almeida, C.V.; Antiga, E.; Lulli, M. Oral and Topical Probiotics and Postbiotics in Skincare and Dermatological Therapy: A Concise Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chilicka, K.; Dzieńdziora-Urbińska, I.; Szyguła, R.; Asanova, B.; Nowicka, D. Microbiome and Probiotics in Acne Vulgaris-A Narrative Review. Life 2022, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shields, A.; Ly, S.; Wafae, B.; Chang, Y.F.; Manjaly, P.; Archila, M.; Heinric, M.; Drake, L.; Mostaghi, A.; Barbier, J. The role of oral nutraceuticals as adjunctive therapy to reduce side effects from isotretinoin: A systematic review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boby, A.; Lee, G.; Natarelli, N.; Correa, L. Using probiotics to treat acne vulgaris: Systematic review. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-López, V.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Ruzafa-Costas, B.; Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-Moratalla, L. Probiotics in the Therapeutic Arsenal of Dermatologists. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Searle, T.; Al-Niaimi, F.; Ali, F.R. Modulation of the microbiome: A paradigm shift in the treatment of acne. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 50, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, M.R.; Akter, S.; Tamanna, S.K.; Mazumder, L.; Esti, I.Z.; Banerjee, S.; Akter, S.; Hasan, R.; Acharjee, M.; Hossain, S.; et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: Gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sathikulpakdee, S.; Kanokrungsee, S.; Vitheejongjaroen, P.; Kamanamool, N.; Udompataikul, M.; Taweechotipatr, M. Efficacy of probiotic-derived lotion from Lactobacillus paracasei MSMC 39-1 in mild to moderate acne vulgaris, randomized controlled trial. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5092–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Guo, C.; Wang, Q.; Feng, C.; Duan, Z. A pilot study on the efficacy of topical lotion containing anti-acne postbiotic in subjects with mild -to -moderate acne. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1064460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, H.; Feng, C.; Zhang, T.; Martínez-Ríos, V.; Martorell, P.; Tortajada, M.; Cheng, S.; Cheng, S.; Duan, Z. Effects of a lotion containing probiotic ferment lysate as the main functional ingredient on enhancing skin barrier: A randomized, self-control study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeer, S.; Oerlemans, E.F.M.; Claes, I.; Henkens, T.; Delanghe, L.; Wuyts, S.; Spacova, I.; van den Broek, M.F.L.; Tuyaerts, I.; Wittouck, S.; et al. Selective targeting of skin pathobionts and inflammation with topically applied lactobacilli. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cui, H.; Feng, C.; Guo, C.; Duan, Z. Development of Novel Topical Anti-Acne Cream Containing Postbiotics for Mild-to-Moderate Acne: An Observational Study to Evaluate Its Efficacy. Indian J. Dermatol. 2022, 67, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Espinoza-Monje, M.; Campos, J.; Alvarez Villamil, E.; Jerez, A.; Dentice Maidana, S.; Elean, M.; Salva, S.; Kitazawa, H.; Villena, J.; García-Cancino, A. Characterization of Weissella viridescens UCO-SMC3 as a Potential Probiotic for the Skin: Its Beneficial Role in the Pathogenesis of Acne Vulgaris. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Randomization | Deviations from Interventions | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement | Reported Results | Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim 2021 [24] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Eguren 2024 [22] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Atefi 2025 [23] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| Study | Outcome | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim 2021 [24] | Change in inflammatory lesion count | No downgrade (Low risk) | Downgraded (I2 = 72%) | No downgrade | Downgraded (small N) | No downgrade | MODERATE |

| Eguren 2024 [22] | Change in inflammatory lesion count | No downgrade (Low risk) | Downgraded (I2 = 72%) | No downgrade | Downgraded (small N) | No downgrade | MODERATE |

| Atefi 2025 [23] | Change in inflammatory lesion count | Downgraded (Some concerns) | Downgraded (I2 = 72%) | No downgrade | Downgraded (small N) | No downgrade | LOW |

| Study | Year | Region | Sample Size (n) | Duration (Weeks) | Probiotic Intervention | Comparator | Primary Outcome | Secondary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim 2021 [24] | 2021 | Asia | 80 | 12 | Lactobacillus plantarum CJLP55 (multi-strain) | Placebo | Inflammatory lesion count | Non-inflammatory lesions; Total lesion count; Adverse events |

| Eguren 2024 [22] | 2024 | Europe | 90 | 10 | Lactobacillus paracasei (single strain) | Placebo | Inflammatory lesion count | Global severity scale; Total lesions; Adverse events |

| Atefi 2025 [23] | 2025 | Asia | 61 | 8 | Bifidobacterium lactis + Lactobacillus acidophilus (multi-strain) | Adjunct topical therapy | Inflammatory lesion count | Non-inflammatory lesions; Total lesion count; Safety outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tjiu, J.-W.; Lu, C.-F. Oral Probiotics in Acne vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials. Medicina 2025, 61, 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122152

Tjiu J-W, Lu C-F. Oral Probiotics in Acne vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122152

Chicago/Turabian StyleTjiu, Jeng-Wei, and Chia-Fang Lu. 2025. "Oral Probiotics in Acne vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122152

APA StyleTjiu, J.-W., & Lu, C.-F. (2025). Oral Probiotics in Acne vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials. Medicina, 61(12), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122152