Phenotypic Remodeling of γδ T Cells in Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Histopathological Analysis

2.3. Isolation and Immunophenotyping of γδ T Cells

2.4. Flow Cytometry Staining and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Methods

2.5.1. Statistical Data Analysis

2.5.2. Data Reduction

2.5.3. Regression Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Subject Characteristics

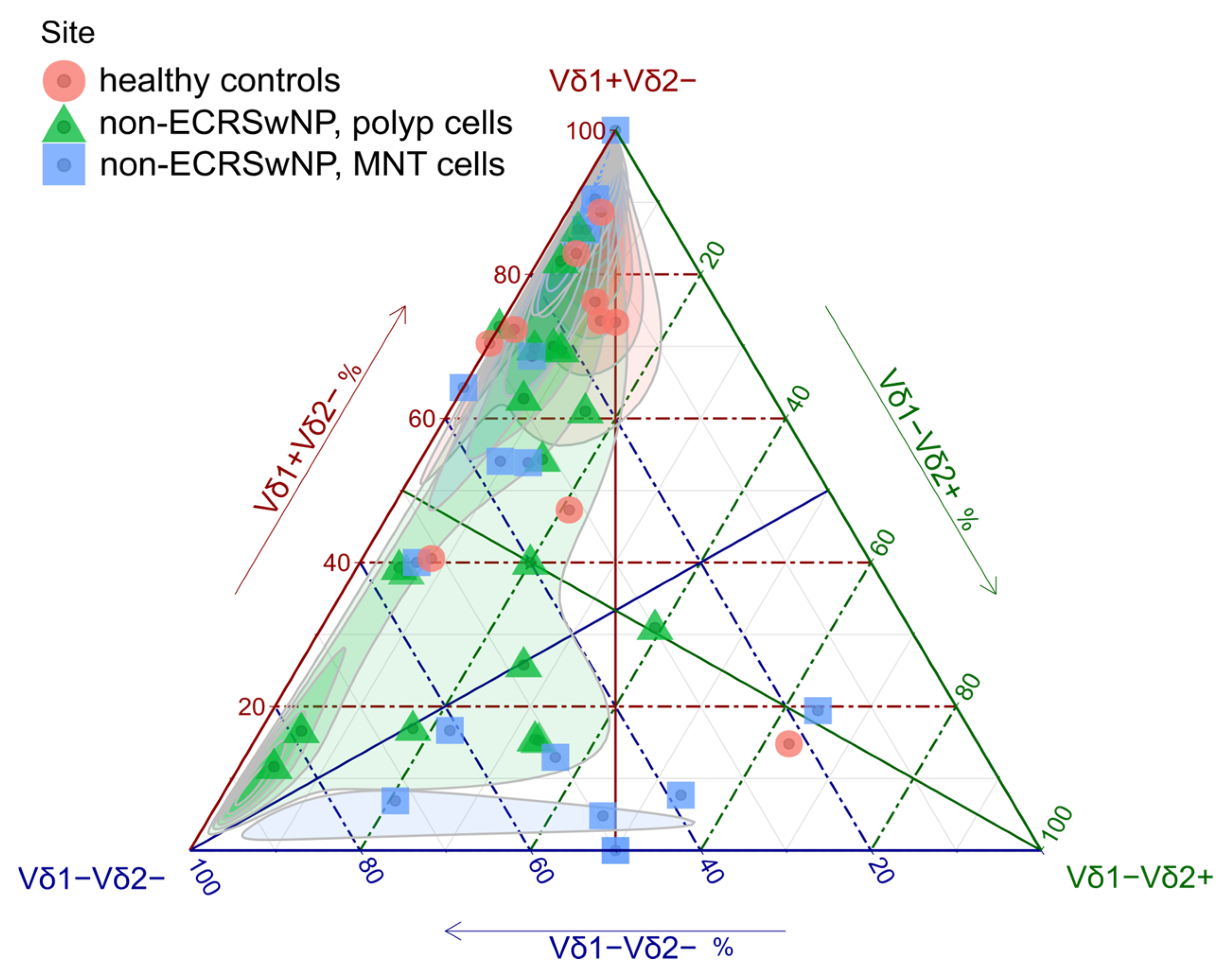

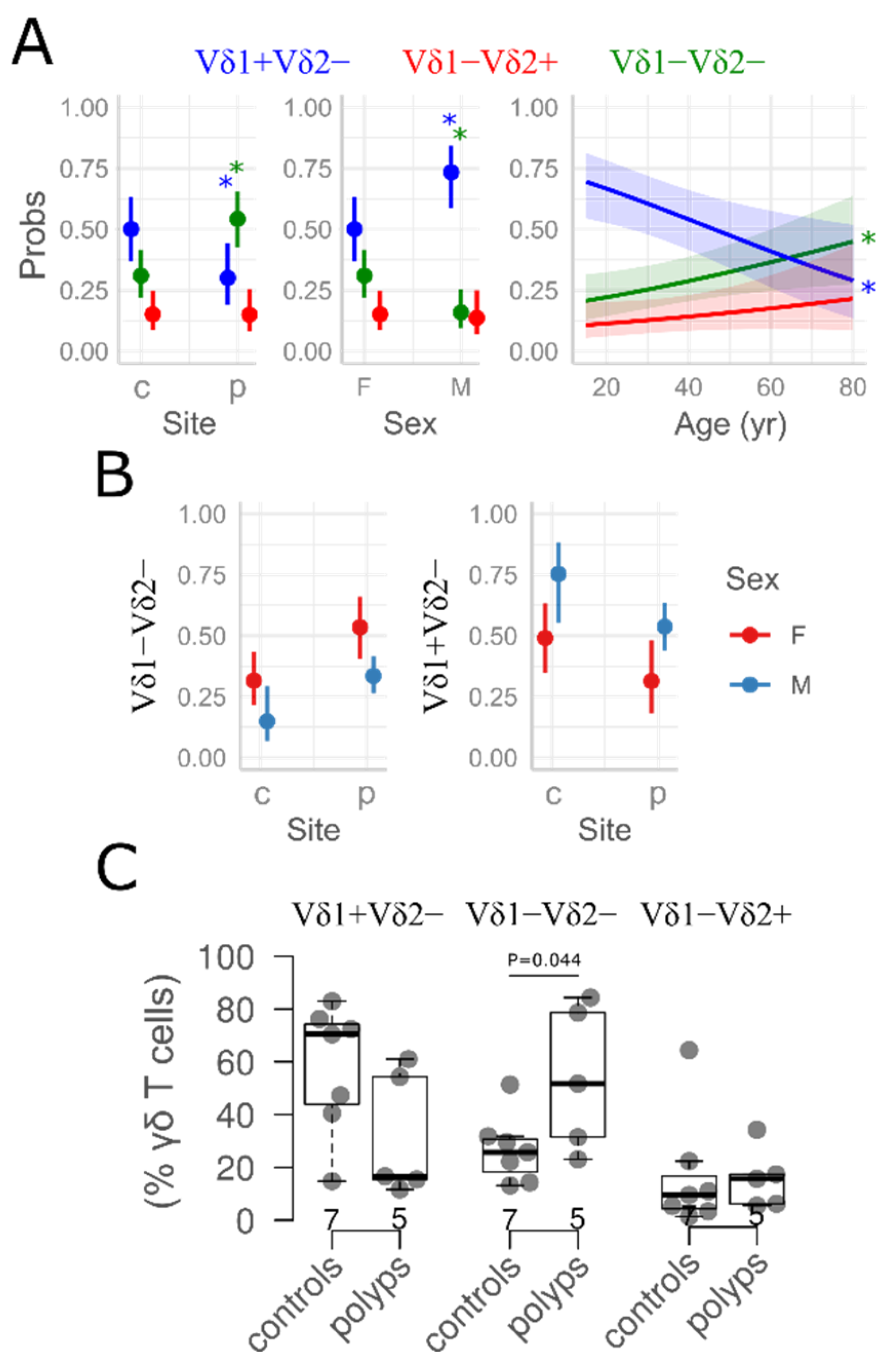

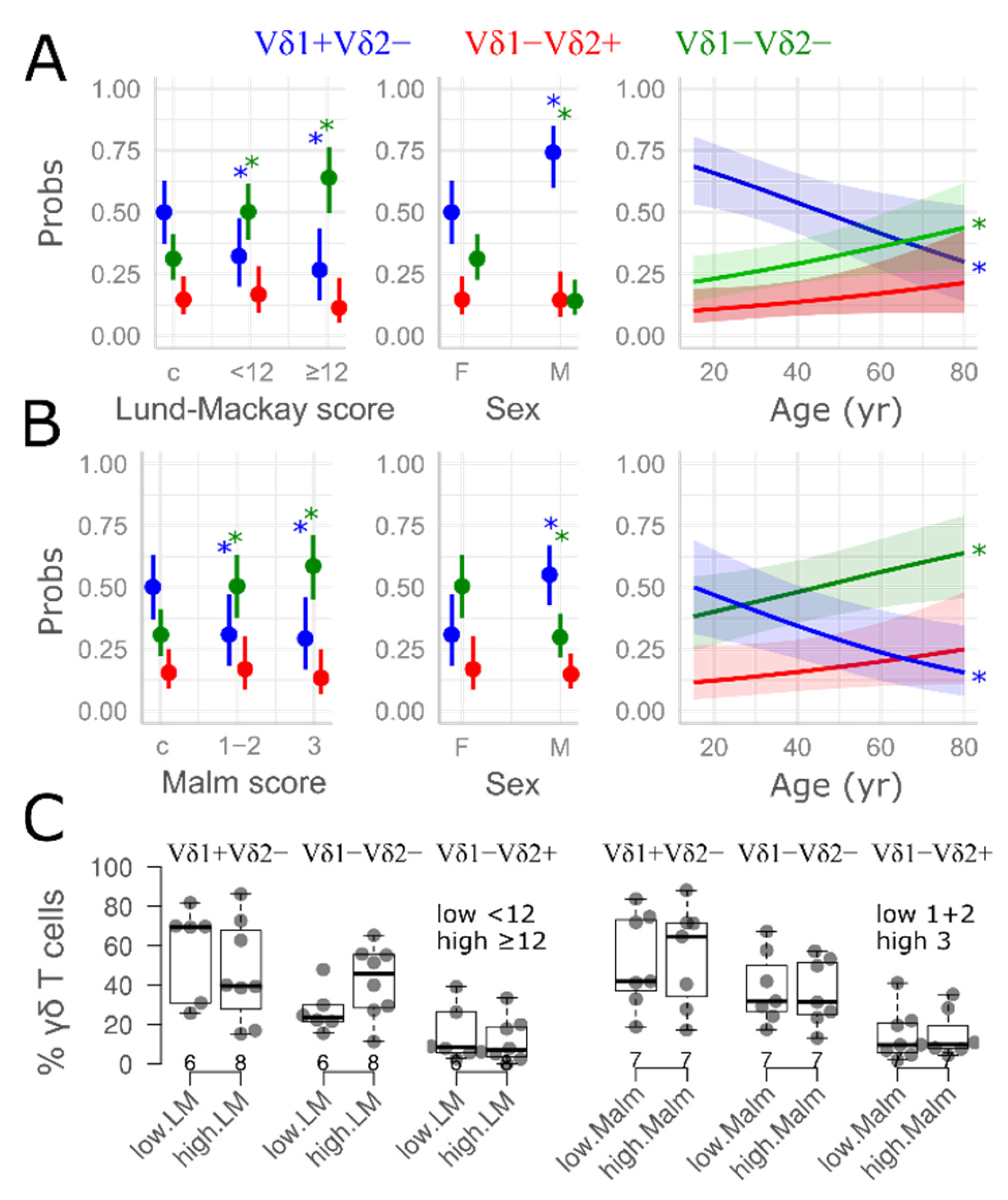

3.2. γδ T Cell Distribution in Nasal Mucosa

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaliner, M.A.; Osguthorpe, J.D.; Fireman, P.; Anon, J.; Georgitis, J.; Davis, M.L.; Naclerio, R.; Kennedy, D. Sinusitis: Bench to bedside. Current findings, future directions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1997, 99 Pt 3, S829–S848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melén, I. Chronic Sinusitis: Clinical and Pathophysiological Aspects. Acta Otolaryngol 1994, 114 (Suppl. S515), 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethbridge-Çejku, M.; Rose, D.; Vickerie, J. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National health interview survey, 2004. Vital Health Stat. 10 2006, 228, 1–164. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, D.L.; Collins, J.G.; Coles, R. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 1997. Vital Health Stat. 10 2002, 211, 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Gevaert, E.; Lou, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Bachert, C.; Zhang, N. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Asia. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C.; Gevaert, P.; Cauwenberge, P.V. Staphylococcus aureus superantigens and airway disease. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2002, 2, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benninger, M.S.; Anon, J.; Mabry, R.L. The medical management of rhinosinusitis. Head Neck Surg. 1997, 117, S41–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.H.; Ponikau, J.U.; Sherris, D.A.; Congdon, D.; Frigas, E.; Homburger, H.A.; Swanson, M.C.; Gleich, G.J.; Kita, H. Chronic rhinosinusitis: An enhanced immune response to ubiquitous airborne fungi. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 114, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witherden, D.A.; Havran, W.L. Molecular aspects of epithelial γδ T cell regulation. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boismenu, R.; Havran, W.L. An innate view of gamma delta T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, M.H.; Mraz, V.; Geisler, C.; Bonefeld, C.M. γδ T cells and inflammatory skin diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 298, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, D.J.; Neves, J.F.; Sumaria, N.; Pennington, D.J. Understanding the complexity of γδ T-cell subsets in mouse and human. Immunology 2012, 136, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.L.; Born, W.K. γδ T cell subsets: A link between TCR and function? Semin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawankar, R.; Okuda, M.; Suzuki, K.; Okumura, K.; Ra, C. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of nasal mucosal gd T cells in allergic and infectious rhinitis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 153, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Lai, X.; Li, S.; Huang, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; et al. γδT cells contribute to type 2 inflammatory profiles in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 2301–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.T.; Huang, J.C.; Wang, Z.Y.; Huang, Z.Z.; Chang, L.H.; Zhang, G.H. Vγ1+ γδT Cells Are Correlated with Increasing Expression of Eosinophil Cationic Protein and Metalloproteinase-7 in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps Inducing the Formation of Edema. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2017, 9, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Aodeng, S.; Chen, H.; Cai, M.; Huang, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Single-cell profiling identifies mechanisms of inflammatory heterogeneity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papotto, P.H.; Reinhardt, A.; Prinz, I.; Silva-Santos, B. Innately versatile: γδ17 T cells in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 87, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bank, I. The Role of γδ T Cells in Fibrotic Diseases. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2016, 7, e0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, R.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Cipriani, P.; Ghersetich, I.; Lattanzio, R.; Pavan, A.; Pignone, A.; Cagnoni, M.L.; Lotti, T.; Tonietti, G. Circulating Vdelta1+ T cells are activated and accumulate in the skin of systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, B.; Yurovsky, V.V. Oligoclonal expansion of V delta 1+ gamma/delta T-cells in systemic sclerosis patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 756, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinol. J. 2020, 58, 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snidvongs, K.; Lam, M.; Sacks, R.; Earls, P.; Kalish, L.; Phillips, P.S.; Pratt, E.; Harvey, R.J. Structured histopathology profiling of chronic rhinosinusitis in routine practice. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012, 2, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M. DirichletReg: Dirichlet Regression for Compositional Data in R; Research Report Series; Department of Statistics and Mathematics, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, P. brms: An R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models Using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, R.E.; Raftery, A.E. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995, 90, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Machler, M.; Bolker, B.M. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for Zero-inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, N. Further analysis of the data by Akaike’s information criterion and the finite corrections. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1978, A7, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvich, C.M.; Tsai, C.L. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika 1989, 76, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. ggeffects: Tidy Data Frames of Marginal Effects from Regression Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plužarić, V.; Štefanić, M.; Mihalj, M.; Tolušić Levak, M.; Muršić, I.; Glavaš-Obrovac, L.; Petrek, M.; Balogh, P.; Tokić, S. Differential Skewing of Circulating MR1-Restricted and γδ T Cells in Human Psoriasis Vulgaris. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 572924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Venken, K.; Jacques, P.; Mortier, C.; Labadia, M.E.; Decruy, T.; Coudenys, J.; Hoyt, K.; Wayne, A.L.; Hughes, R.; Turner, M.; et al. RORγt inhibition selectively targets IL-17 producing iNKT and γδ-T cells enriched in Spondyloarthritis patients. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mei, Z.; Khalil, M.A.; Guo, Y.; Li, D.; Banerjee, A.; Taheri, M.; Kratzmeier, C.M.; Chen, K.; Lau, C.L.; Luzina, I.G.; et al. Stress-induced eosinophil activation contributes to postoperative morbidity and mortality after lung resection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadl4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu, A.T.; O’Donoghue, R.J.J.; Tsantikos, E.; Gottschalk, T.A.; Borger, J.G.; Gherardin, N.A.; Xu, C.; Koay, H.F.; Godfrey, D.I.; Ernst, M.; et al. An unconventional T cell nexus drives HCK-mediated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in mice. EBioMedicine 2025, 115, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dunon, D.; Courtois, D.; Vainio, O.; Six, A.; Chen, C.H.; Cooper, M.D.; Dangy, J.P.; Imhof, B.A. Ontogeny of the immune system: Gamma/delta and alpha/beta T cells migrate from thymus to the periphery in alternating waves. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jensen, K.D.; Chien, Y.H. Thymic maturation determines gammadelta T cell function, but not their antigen specificities. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanchez Sanchez, G.; Tafesse, Y.; Papadopoulou, M.; Vermijlen, D. Surfing on the waves of the human γδ T cell ontogenic sea. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 315, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gay, L.; Mezouar, S.; Cano, C.; Frohna, P.; Madakamutil, L.; Mège, J.-L.; Olive, D. Role of Vγ9vδ2 T lymphocytes in infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 928441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Xiang, Z.; Yin, Z.; Kabelitz, D. γδ T cells: Origin and fate, subsets, diseases and immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, M.; Dimova, T.; Shey, M.; Briel, L.; Veldtsman, H.; Khomba, N.; Africa, H.; Steyn, M.; Hanekom, W.A.; Scriba, T.J.; et al. Fetal public Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expand and gain potent cytotoxic functions early after birth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18638–18648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davey, M.S.; Willcox, C.R.; Hunter, S.; Kasatskaya, S.A.; Remmerswaal, E.B.M.; Salim, M.; Mohammed, F.; Bemelman, F.J.; Chudakov, D.M.; Oo, Y.H.; et al. The human Vδ2+ T-cell compartment comprises distinct innate-like Vγ9+ and adaptive Vγ9- subsets. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Papadopoulou, M.; Tieppo, P.; McGovern, N.; Gosselin, F.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Goetgeluk, G.; Dauby, N.; Cogan, A.; Donner, C.; Ginhoux, F. TCR sequencing reveals the distinct development of fetal and adult human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieppo, P.; Papadopoulou, M.; Gatti, D.; McGovern, N.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Gosselin, F.; Goetgeluk, G.; Weening, K.; Ma, L.; Dauby, N. The human fetal thymus generates invariant effector γδ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimova, T.; Brouwer, M.; Gosselin, F.; Tassignon, J.; Leo, O.; Donner, C.; Marchant, A.; Vermijlen, D. Effector Vγ9Vδ2 T cells dominate the human fetal γδ T-cell repertoire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E556–E565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudev, A.; Ying, C.T.T.; Ayyadhury, S.; Puan, K.J.; Andiappan, A.K.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Shadan, N.B.; Mustafa, S.; Low, I.; Rotzschke, O.; et al. γ/δ T cell subsets in human aging using the classical α/β T cell model. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014, 96, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.T.Y.; Wistuba-Hamprecht, K.; Xu, W.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Vasudev, A.; Lee, B.T.K.; Pawelec, G.; Puan, K.J.; Rotzschke, O.; Ng, T.P.; et al. Vδ2+ and α/Δ T cells show divergent trajectories during human aging. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 44906–44918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccamo, N.; Dieli, F.; Wesch, D.; Jomaa, H.; Eberl, M. Sex-specific phenotypical and functional differences in peripheral human Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michishita, Y.; Hirokawa, M.; Guo, Y.; Abe, Y.; Liu, J.; Ubukawa, K.; Fujishima, N.; Fujishima, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Kameoka, Y. Age-associated alteration of γδ T-cell repertoire and different profiles of activation-induced death of Vδ1 and Vδ2 T cells. Int. J. Hematol. 2011, 94, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lau, Z.W.X.; Fulop, T.; Larbi, A. The Aging of γδ T Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.I.; Caron, D.P.; Wells, S.B.; Guyer, R.; Szabo, P.; Rainbow, D.; Ergen, C.; Rybkina, K.; Bradley, M.C.; Matsumoto, R.; et al. Human γδ T cells in diverse tissues exhibit site-specific maturation dynamics across the life span. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadn3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanz, M.; Mann, B.T.; Ryan, P.L.; Bosque, A.; Pennington, D.J.; Hackstein, H.; Soriano-Sarabia, N. Deep characterization of human γδ T cell subsets defines shared and lineage-specific traits. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenna, T.; Golden-Mason, L.; Norris, S.; Hegarty, J.E.; O’Farrelly, C.; Doherty, D.G. Doherty, Distinct subpopulations of γδ T cells are present in normal and tumor-bearing human liver. Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, M.R.; Elliott, L.; Hussey, S.; Mahmud, N.; Kelly, J.; Doherty, D.G.; Feighery, C.F. Persistent changes in circulating and intestinal γδ T cell subsets, invariant natural killer T cells and mucosal-associated invariant T cells in children and adults with coeliac disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déchanet, J.; Merville, P.; Lim, A.; Retière, C.; Pitard, V.; Lafarge, X.; Michelson, S.; Méric, C.; Hallet, M.M.; Kourilsky, P.; et al. Implication of γδ T cells in the human immune response to cytomegalovirus. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.; Madrigal, A.J.; Grace, S.; Sivakumaran, J.; Kottaridis, P.; Mackinnon, S.; Travers, P.J.; Lowdell, M.W. The role of Vδ2-negative γδ T cells during cytomegalovirus reactivation in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2010, 116, 2164–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrasca, A.; Melo, A.M.; Breen, E.P.; Doherty, D.G. Human Vδ3+ γδ T cells induce maturation and IgM secretion by B cells. Immunol. Lett. 2018, 196, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschenbacher, W.; Straesser, M.; Knoeddler, A.; Li, R.C.; Borish, L. Biologics for the Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis, Chronic Rhinosinusitis, and Nasal Polyposis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2020, 40, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laidlaw, T.M.; Prussin, C.; Panettieri, R.A.; Lee, S.; Ferguson, B.J.; Adappa, N.D.; Lane, A.P.; Palumbo, M.L.; Sullivan, M.; Archibald, D.; et al. Dexpramipexole depletes blood and tissue eosinophils in nasal polyps with no change in polyp size. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, E61–E66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Controls | Polyps, Non-ECRSwNP | MannWhitney p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) | (n = 19) | ||

| Age (yr) | 42 [29, 48] | 54 [35, 65] | 0.108 |

| SNOT22 | 11 [2, 20.25] | 35 [23, 53] | 0.224 |

| SNOT20 | 29 [15, 40.25] | 41 [27, 60] | 0.0078 |

| Japan | 13 [5, 26] | 22 [13, 46] | 0.108 |

| Nose.score | 7 [5, 10] | 16 [13, 17] | 0.0069 |

| Lund–Mackay score | - | 11 [8.0, 16] | - |

| IgE (pg/mL) | 62.50 [26, 114.3] | 115 [37.5, 271] | 0.347 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.3 [0.68, 1.83] | 1.84 [1.39, 2.95] | 0.148 |

| Sex | 0.046 * | ||

| F | 7 (70.0%) | 5 (26.3%) | |

| M | 3 (30.0%) | 14 (73.7%) | |

| LMI | |||

| controls | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| high | 0 (0%) | 9 (47.4%) | |

| low | 0 (0%) | 10 (52.6%) | |

| Malm grade | - | ||

| controls | 10 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0 | 7 | |

| 3 | 0 | 9 | |

| Inhalant allergens | 0.236 * | ||

| neg | 4 (40.0%) | 13 (68.4%) | |

| pos | 6 (60.0%) | 6 (31.6%) | |

| Nutritive allergens | 0.298 * | ||

| neg | 10 (100%) | 16 (84.2%) | |

| pos | 0 (0%) | 3 (15.8%) | |

| Eosinophils | 0.431 * | ||

| neg | 8 (80.0%) | 12 (63.2%) | |

| pos | 2 (20.0%) | 7 (37%) |

| Cell Population | Controls | p, Non-ECRSwNP | MNT, Non-ECRSwNP | Mann–Whitney p (p vs. Controls) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10) | (N = 19) | (N = 16) | ||

| Ly (% Parent) | 40 [30, 50] | 40 [40, 60] | 30 [20, 40] | 0.63 |

| [Min, Max] | [20, 70] | [10, 70] | [10, 70] | |

| Ly (% Total) | 30 [20, 40] | 30 [20, 40] | 20 [20, 30] | 0.945 |

| [Min, Max] | [20, 50] | [5, 60] | [8, 40] | |

| T (%Parent) | 40 [40, 50] | 50 [30, 60] | 30 [10, 50] | 0.909 |

| [Min, Max] | [6, 80] | [5, 80] | [6, 80] | |

| T (% Total) | 10 [8, 20] | 10 [7, 20] | 5 [4, 8] | 0.872 |

| [Min, Max] | [3, 30] | [2, 30] | [1, 20] | |

| γδ (% T) | 4 [3, 8] | 4 [3, 7] | 4 [3, 6] | 0.872 |

| [Min, Max] | [2, 10] | [2, 20] | [0.9, 20] | |

| γδ (% ly) | 0.5 [0.2, 1] | 0.5 [0.3, 0.7] | 0.3 [0.08, 0.4] | 0.89 |

| [Min, Max] | [0.09, 3] | [0.1, 2] | [0.03, 2] | |

| Vδ1−Vδ2+ (%γδ) | 9 [4, 10] | 8 [5, 20] | 20 [5, 50] | 0.646 |

| [Min, Max] | [0, 60] | [0, 40] | [0, 60] | |

| Vδ1+Vδ2− (%γδ) | 70 [50, 80] | 40 [20, 70] | 30 [7, 70] | 0.037 |

| [Min, Max] | [10, 90] | [10, 90] | [0, 100] | |

| Vδ1−Vδ2− (%γδ) | 20 [10, 30] | 30 [20, 50] | 40 [20, 50] | 0.018 |

| [Min, Max] | [7, 50] | [10, 80] | [0, 70] | |

| Vδ1−Vδ2+ (% T) | 0.3 [0.2, 0.5] | 0.4 [0.2, 1] | 0.5 [0.3, 1] | 0.748 |

| [Min, Max] | [0, 2] | [0, 3] | [0, 4] | |

| Vδ1+Vδ2− (% T) | 2 [1, 6] | 2 [0.8, 3] | 1 [0.3, 3] | 0.302 |

| [Min, Max] | [0.5, 10] | [0.4, 10] | [0, 10] | |

| Vδ1−Vδ2− (% T) | 0.9 [0.6, 2] | 2 [1, 3] | 1 [0.9, 2] | 0.162 |

| [Min, Max] | [0.3, 2] | [0.4, 5] | [0, 6] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bogović, V.; Štefanić, M.; Milanković, S.G.; Zubčić, Ž.; Mihalj, H.; Tokić, S.; Mihalj, M. Phenotypic Remodeling of γδ T Cells in Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122143

Bogović V, Štefanić M, Milanković SG, Zubčić Ž, Mihalj H, Tokić S, Mihalj M. Phenotypic Remodeling of γδ T Cells in Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122143

Chicago/Turabian StyleBogović, Vjeran, Mario Štefanić, Stjepan Grga Milanković, Željko Zubčić, Hrvoje Mihalj, Stana Tokić, and Martina Mihalj. 2025. "Phenotypic Remodeling of γδ T Cells in Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122143

APA StyleBogović, V., Štefanić, M., Milanković, S. G., Zubčić, Ž., Mihalj, H., Tokić, S., & Mihalj, M. (2025). Phenotypic Remodeling of γδ T Cells in Non-Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Medicina, 61(12), 2143. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122143