1. Introduction

Glaucoma represents a chronic, progressive optic neuropathy characterized by irreversible loss of retinal ganglion cells and visual field defects [

1], remaining one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide [

2]. As life expectancy increases worldwide, the prevalence of glaucoma is projected to rise substantially, with estimates suggesting that more than 110 million people will be affected by 2040 [

3]. This global burden underscores the need for therapeutic strategies that are both effective and sustainable over a lifetime of management. The disease’s asymptomatic course in early stages and its chronic nature require long-term treatment adherence and monitoring, making approaches that minimize patient burden and preserve ocular surface health particularly valuable [

4]. Advances in laser and pharmacologic technologies now reflect a shift toward minimally invasive, patient-centered interventions that can maintain stable intraocular pressure (IOP) while reducing treatment complexity and improving quality of life [

5].

Despite the continuous development of neuroprotective strategies, reduction in IOP remains the only evidence-based intervention proven to delay or prevent disease progression. In clinical practice this is achieved with medications, laser therapies, or surgery. Laser trabeculoplasty has long been an important non-invasive intervention for open-angle glaucoma management, and it represents an important intermediate step between medical and surgical treatment, aiming to improve aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork (TM) without altering the integrity of ocular structures. Beginning with argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) in 1979 and later selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) in the 1990s, laser treatments have offered IOP-lowering efficacy comparable to medications, with SLT having the advantage of less tissue damage and repeatability [

6]. While ALT provided effective IOP reduction, it induced structural scarring, limiting repeatability. On the other hand, SLT, employing a Q-switched 532 nm Nd:YAG laser, selectively targeted pigmented TM cells, minimizing collateral damage but occasionally producing inflammation or transient IOP spikes [

7].

Topical pharmacologic therapy is the first-line approach in most cases; however, poor adherence, reported to be as low as 60% and ocular surface toxicity from preservatives frequently limit its long-term effectiveness [

8], and may lead to medication discontinuation [

9]. In this context, there is growing emphasis on treatment strategies that combine efficacy with safety, comfort, and sustainability. The therapy paradigm has gradually changed due to advancements in laser technology, moving from destructive to subthreshold modalities that preserve tissue integrity while causing the trabecular meshwork to biologically activate. This transition reflects a broader evolution in glaucoma care toward individualized, minimally invasive, and repeatable approaches that can be seamlessly integrated into chronic disease management [

10,

11].

Consequently, the search for a safe, repeatable, and effective laser alternative has led to the development of micropulse laser trabeculoplasty (MLT), a newer innovation introduced in the mid-2000s that delivers laser energy in a subthreshold manner using a duty cycle (typically 15%) of very short laser pulses separated by brief rest intervals. This micropulse emission pattern allows thermal relaxation between pulses, limiting heat accumulation in the TM and minimizing collateral tissue damage, postoperative inflammation, and scarring compared with conventional continuous-wave laser applications. By avoiding coagulative damage, MLT preserves the integrity of the TM, making the procedure safer, less painful, and theoretically allowing for repetition if needed. Early studies have indicated that MLT is a promising option for patients with ocular hypertension or open-angle glaucoma (including pseudoexfoliative and pigmentary glaucoma), particularly in those who respond inadequately to medical therapy or seek to defer invasive surgery [

12].

The biologic response to MLT involves cellular and biochemical activation rather than tissue ablation, with stimulation of TM endothelial and macrophage activity, upregulation of cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, and remodeling of extracellular matrix pathways that enhance aqueous outflow while preserving TM morphology [

13]. Experimental data confirm that sub-threshold stimulation up-regulates metalloproteinases and modulates oxidative stress pathways, offering a non-destructive mechanism of trabecular activation distinct from thermal ablation [

14].

Clinically, MLT is typically performed using a 577 nm yellow diode laser, 200–300 µm spot size, 300 ms exposure, and 1000–1500 mW power applied over 180° or 360° of the angles under gonioscopy control. Several randomized and observational studies have confirmed its efficacy and safety under these parameters. A long-term series with 577 nm MLT reported sustained IOP reductions of 12–17% over 36–48 months, with acceptable retreatment rates and no significant adverse events [

15]. Similarly, a cohort study of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) eyes demonstrated that MLT achieved durable IOP lowering with minimal anterior chamber inflammation and without peripheral anterior synechiae [

16]. More recently, a systemic review reinforced these findings, emphasizing that MLT is both effective and safe as a primary or adjunctive therapy for glaucoma and ocular hypertension but that standardization of technique and longer follow-up are required to optimize outcomes [

12].

Current evidence suggests that MLT achieves mean IOP reductions of 15–25% across open-angle glaucoma phenotypes, with higher baseline IOP predicting better response and consistent efficacy in pigmentary and pseudoexfoliative forms. Because the micro pulse technique prevents thermal injury, it can be safely applied in heavily pigmented TM without inducing inflammation or synechiae, and pseudophakia has not been shown to compromise outcomes [

17]. MLT’s non-destructive nature and minimal postoperative inflammation profile also explain the excellent tolerability reported across multiple studies, where no significant IOP spikes (>5 mmHg), endothelial injury, or visual acuity changes were observed [

18]. Moreover, clinical evidence indicates that MLT may allow partial reduction in topical medication burden while maintaining stable IOP control, a finding of increasing practical relevance for elderly and polytreated glaucoma patients [

12].

The combination of repeatability, minimal discomfort, and lack of structural damage supports its inclusion as a viable intermediate option between pharmacologic and surgical management. Because of these properties, MLT aligns with the principles of modern glaucoma management, emphasizing tissue preservation, repeatability, and patient-centered care. It also holds potential for earlier therapeutic intervention, particularly in patients where adherence to pharmacologic therapy is suboptimal or ocular surface disease limits tolerance to multiple topical agents. The increasing amount of research and rapid clinical adoption of MLT underscore the need for empirical outcomes that verify its reproducibility, safety, and applicability across diverse patient populations [

19].

This research evaluated the efficacy, safety, and clinical applicability of MLT in a real-world cohort of patients with open-angle glaucoma at various stages of severity and ocular hypertension. The analysis included POAG of varying severity, as well as pseudoexfoliative and pigmentary subtypes. The primary objective was to quantify IOP reduction over the short- to medium-term and assess its consistency across diagnostic categories. Secondary outcomes included changes in visual and refractive parameters and adverse events. The study also aimed to define MLT’s role within current glaucoma management, particularly relative to SLT. By applying standardized parameters and correlating clinical outcomes with recent evidence, this work provides an updated assessment of MLT as a reproducible and minimally invasive treatment option in contemporary glaucoma care.

4. Discussion

Glaucoma management continues to evolve toward treatment strategies that achieve sustained IOP control while minimizing structural damage and improving long-term tolerability. Within this therapeutic continuum, laser trabeculoplasty occupies a key position between topical pharmacotherapy and incisional surgery, providing an effective, repeatable, and minimally invasive method of enhancing trabecular outflow [

12]. This study investigated the IOP-lowering efficacy and safety profile of micropulse laser trabeculoplasty (MLT) in eyes with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension.

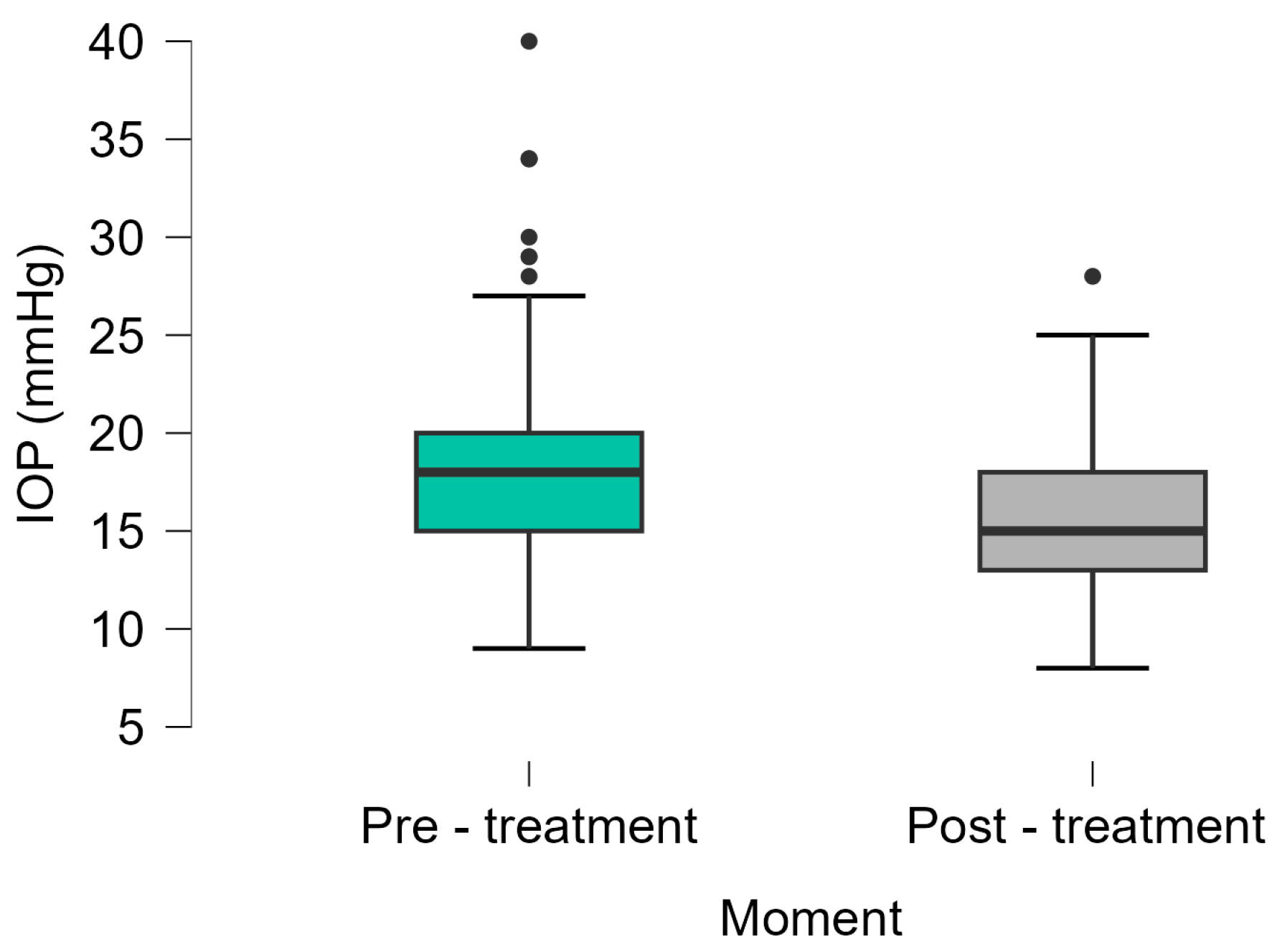

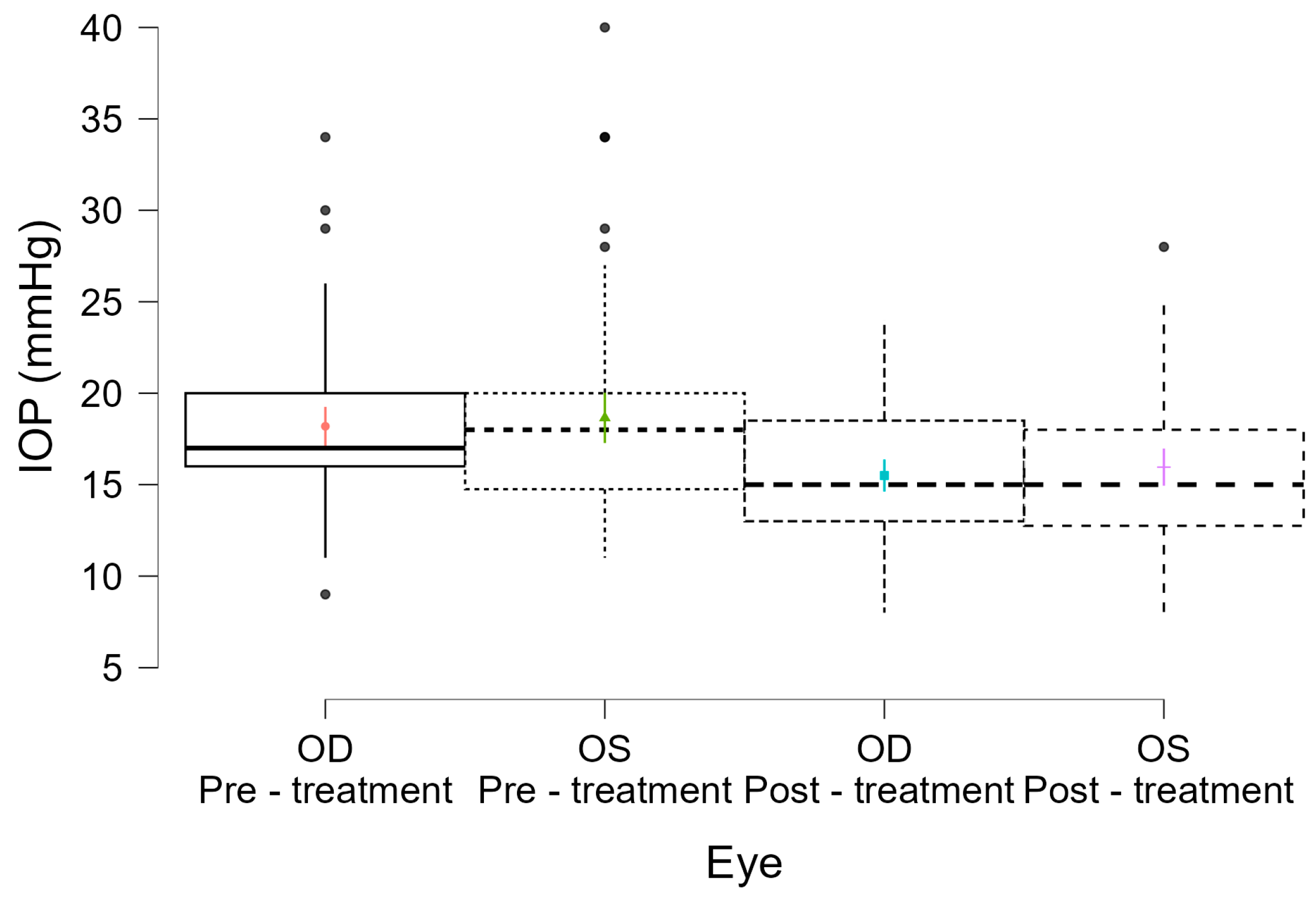

In our cohort, a single 360° MLT session resulted in a modest but statistically significant IOP reduction of approximately 2.6 mmHg (14.2%) from a baseline mean of 18.15 mmHg. This effect was confirmed using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model that accounted for inter-eye correlation, repeated measurements, and demographic covariates. The model revealed no significant influence of age, sex, or eye laterality on treatment response (

p > 0.05 G for all), reinforcing the consistency of the effect across patient subgroups. Furthermore, interaction terms between treatment and both sex and age were tested and found to be non-significant, indicating that the IOP-lowering effect of MLT did not differ meaningfully by demographic profile. This degree of pressure lowering is clinically relevant, particularly in a pretreated population where most patients were already receiving multiple topical agents. It is well recognized that the efficacy of trabeculoplasty is inversely related to baseline IOP: eyes with higher initial values tend to show greater reductions, whereas those closer to target levels may experience smaller, but still meaningful, decreases [

12]. This ceiling effect reflects the finite physiological capacity of the trabecular meshwork to increase aqueous outflow once near-optimal homeostasis is achieved. Consistent with this, prior studies reported IOP reductions between 18% and 22% during the first 6–12 months post-MLT, confirming the reproducibility of outcomes under real-world conditions [

22,

23,

24].

Beyond mean IOP reduction, our analysis showed that 76.5% of treated eyes reached an IOP ≤ 18 mmHg at follow-up, compared to 50.8% at baseline. Similarly, 31.1% of eyes achieved a ≥20% IOP reduction, and 31.8% experienced a decrease of more than 3 mmHg, thresholds frequently regarded as clinically meaningful in real-world glaucoma care. These outcomes align with previously published MLT studies, where responder rates vary based on disease stage, prior therapy, and baseline IOP [

12,

25].

The pre- and post-treatment IOP distributions also indicated a shift toward tighter clustering within target ranges and a visible reduction in high-IOP outliers. This is important, as eyes with higher IOP variability or persistently elevated pressures, even within the high-teen range, remain at increased risk of progression, as highlighted in recent research on IOP dynamics and glaucoma risk [

26].

The demographic and clinical composition of our cohort is like many glaucoma clinics: predominantly POAG (64.4%), with smaller proportions of pigmentary (14.4%) and pseudoexfoliative glaucomas, and a majority of pseudophakic eyes. This distribution enhances the external validity of our findings and is consistent with other MLT studies reporting similar age and sex distributions in the mid-60s, reflecting the epidemiology of chronic open-angle disease in aging populations [

14,

15]. The lack of association between lens status and IOP response in our series shows that MLT efficacy is independent of pseudophakia or prior cataract surgery, consistent with prior evidence from multicenter cohorts [

25].

Gonioscopy assessment revealed wide-open angles (Shaffer grade 3–4) in most eyes, with one-third presenting anatomical variations such as heavy trabecular pigmentation, Sampaolesi lines, or focal synechiae. These features did not compromise treatment response, indicating that MLT maintains efficacy even in eyes with moderate anatomic heterogeneity. This observation aligns with data showing stable IOP reduction regardless of trabecular pigmentation intensity [

17].

About one-third of patients presented ocular comorbidities such as pseudophakia, mild diabetic retinopathy, or dry age-related macular degeneration, none of which influenced MLT safety or efficacy, corroborating prior findings that the procedure can be safely performed in eyes with concurrent ocular pathology [

12]. Taken together with the GEE findings, these convergent data indicate that the IOP-lowering effect of MLT in our cohort is unlikely to be an artifact of measurement method or statistical approach but rather a consistent treatment signal at both the eye and patient level [

27,

28].

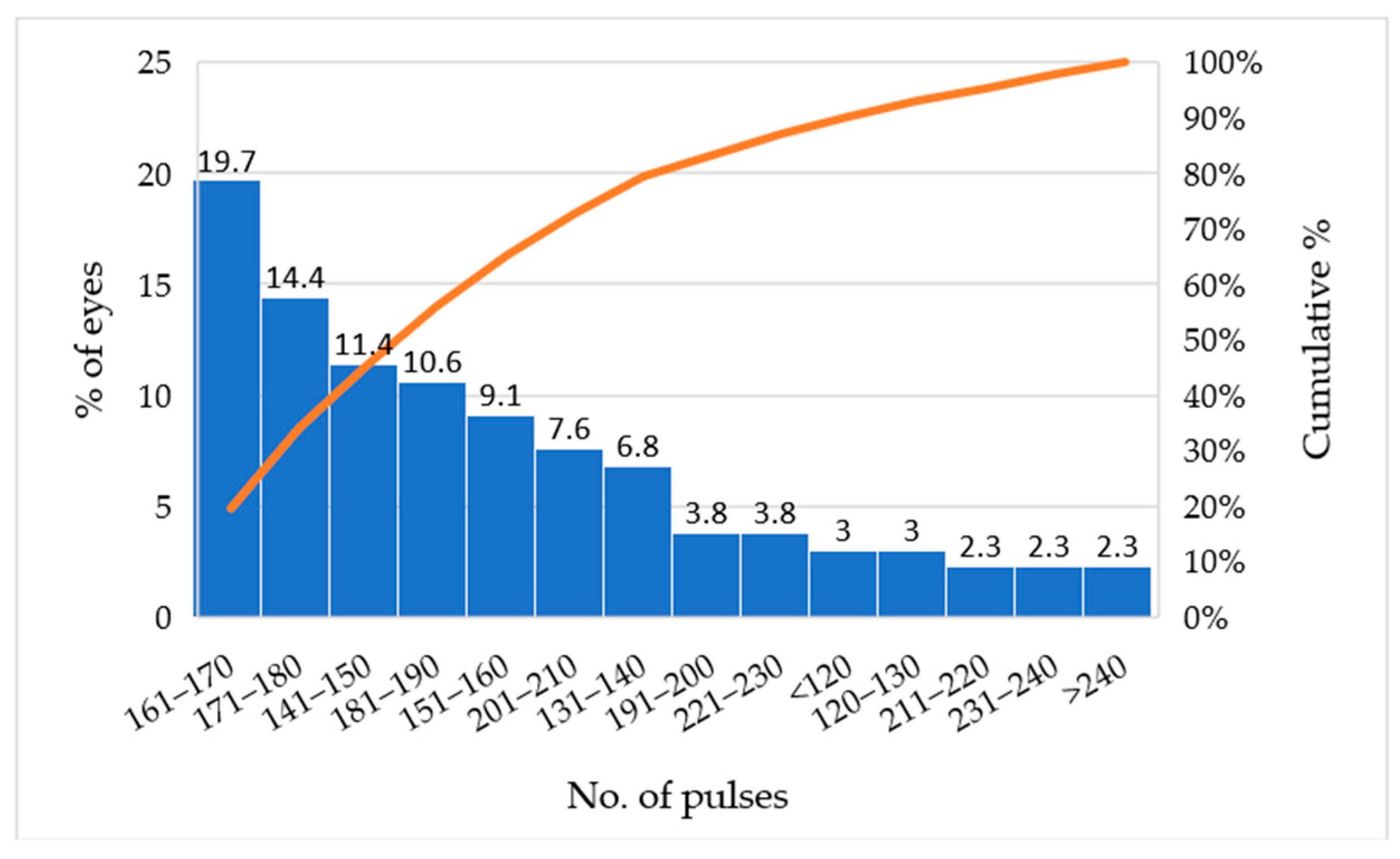

Standardization of laser parameters is an important methodological strength of this study. Nearly all eyes underwent 360° MLT using a 300 µm spot, 300 ms exposure, 15% duty cycle, and 1000 mW power, settings concordant with those employed in controlled trials [

15,

29]. The use of full-angle application likely contributed to the uniform response, minimizing sectoral variability within the trabecular meshwork. The subthreshold micropulse mechanism, defined by microsecond pulses separated by thermal relaxation intervals, achieves biological stimulation without tissue destruction, explaining the absence of inflammatory reaction or peripheral anterior synechiae in our cohort. This biophysical mechanism differentiates MLT from earlier ALT and SLT approaches. ALT uses continuous-wave thermal energy that produces coagulative damage and trabecular scarring, limiting repeatability. In contrast, SLT employs selective photothermolysis and has been shown not to induce significant structural damage, although mild and transient cellular stress responses may occur [

30,

31].

In our study, this standardized protocol was applied over 360° of the trabecular meshwork in almost all eyes, with only a very small minority receiving sectoral treatment because of focal synechiae or suboptimal angle visualization. Although these few sectoral cases are too rare to permit formal subgroup analysis, the overall homogeneity of IOP reduction suggests that complete 360° application is both feasible and effective in routine practice, in agreement with recent prospective studies that have also favored full-angle MLT delivery [

13,

16]. Previous research reported that 360° 577 nm MLT at either 1000 or 1500 mW produced comparable short-term IOP reductions without compromising corneal structure [

13], while another confirmed sustained pressure-lowering over 35 months with a 360° protocol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension [

16]. These convergent data support the choice of circumferential treatment as a reproducible real-world strategy, reserving more limited sectors for eyes with anatomical constraints.

No patient in our cohort experienced an acute IOP spike > 5 mmHg. The laser’s on–off pulse pattern allows sufficient thermal relaxation between bursts, preventing cumulative energy buildup and minimizing cytokine-mediated trabecular dysfunction [

14,

18]. Moreover, comparative analyses have demonstrated that MLT results in fewer postoperative spikes, less discomfort, and comparable long-term pressure control [

32,

33]. In our series, only 3.8% of eyes showed a transient rise of ≤4 mmHg within the first hour, resolving without treatment, findings that were clinically mild and not associated with vision loss.

Visual and refractive stability throughout follow-up further supports the atraumatic nature of MLT. The absence of visual acuity loss or refractive change indicates that subthreshold photostimulation preserves the integrity of the cornea and anterior segment. These findings are in line with prospective imaging studies confirming that MLT does not affect endothelial cell density, corneal thickness, or anterior chamber morphology [

18]. Specifically, BCVA remained unchanged (

p = 0.553), reinforcing that the pressure reduction did not come at the expense of visual function. Regarding refraction, most categories were stable; however, the prevalence of hyperopic astigmatism decreased from 12.9% to 3.0% (

p = 0.003). While statistically significant, this effect size is small and likely of limited clinical relevance, potentially reflecting minor corneal biomechanical changes after IOP lowering. The small reduction in hyperopic astigmatism observed in our series was statistically but not clinically significant and may reflect minor corneal biomechanical adjustments after IOP normalization [

34]. This visual stability supports the use of MLT in outpatient settings without postoperative functional limitations. Recent work using dynamic Scheimpflug imaging and indentation devices has shown that pharmacologic or laser-induced IOP reductions can be accompanied by modest decreases in corneal stiffness and modulus without changes in central corneal thickness, particularly in eyes with glaucoma or ocular hypertension [

34,

35]. The small shift in hyperopic astigmatism in our cohort is consistent with these subtle biomechanical adjustments and supports the interpretation that MLT may slightly modulate the anterior segment biomechanical environment without inducing clinically relevant refractive change [

36].

The safety profile in this study was very good. Only mild, transient symptoms such as conjunctival hyperemia (12%) or ocular discomfort (10%) occurred, resolving spontaneously or with short-term NSAID therapy. No cases of peripheral anterior synechiae, corneal edema, hypotony, or visual loss were recorded. These outcomes corroborate large-scale analyses reporting adverse event rates below 5% [

37]. The low rate of inflammatory sequelae underscores the non-destructive, photobiomodulatory nature of MLT. Taken together with the non-significant changes in visual acuity and the absence of sight-threatening events, these observations underscore the favorable benefit–risk profile of MLT in routine care.

Our results suggest that the pre-existing medication load did not appear to limit the IOP-lowering effect of MLT, supporting its potential role as an adjunctive option in patients already receiving maximal tolerated therapy. Previous studies have shown that eyes on two or more agents still achieve an additional 15–20% IOP reduction after MLT [

13], supporting its value in reducing polypharmacy and improving adherence in elderly or ocular surface–compromised individuals. This may position MLT as a useful approach to reduce chronic medication exposure while maintaining therapeutic control.

Another practical advantage of MLT is its repeatability. Because it induces no coagulative scarring, retreatment can be safely performed when IOP begins to rise again. Long-term studies have shown sustained effects for up to three years, though gradual attenuation may occur [

15,

16]. Randomized controlled trials using similar parameters (1000–1500 mW, 15% duty cycle) demonstrated treatment success (≥20% IOP reduction) in up to 75–80% of eyes at six months, with no endothelial loss or corneal edema [

13].

Finally, the absence of significant postoperative complications or visual function loss in this real-world cohort supports the safety advantages of the micropulse approach. Combined with stable anterior segment anatomy and rapid recovery, these findings suggest that MLT may be a suitable outpatient option, particularly for elderly or multimorbid patients who may have limited tolerance for long-term medical therapy. In a cohort study of 296 eyes undergoing micropulse laser trabeculoplasty, no treatment-related complications were reported, and visual outcomes remained stable [

37].

The findings support considering MLT as part of the therapeutic spectrum for glaucoma management, particularly in selected patient groups. For patients on maximal tolerated topical therapy, MLT offers a means of further pressure reduction without the added pharmacologic burden. This advantage is particularly relevant in elderly patients with ocular surface disease or those with poor adherence to multiple drops [

8]. In early-stage glaucoma or ocular hypertension, MLT can serve as a primary intervention, delaying or potentially avoiding the need for chronic medications. This approach aligns with the emerging “laser-first” paradigm supported by current consensus. However, while MLT can postpone escalation toward surgical interventions, it should not be viewed as a substitute for incisional procedures when larger or long-term pressure reductions are required. Instead, it functions as a bridge within the therapeutic continuum, offering a minimally invasive option that can defer, but not replace, more invasive surgery in appropriately selected patients. Its mechanism of subthreshold photostimulation, rather than photodisruption, minimizes collateral damage, allows for safe retreatment, and avoids the need for postoperative corticosteroids [

13].

In comparative studies, MLT and SLT achieve similar long-term efficacy, although SLT may induce slightly greater short-term reductions [

14]. Data from multicenter registries also indicate non-inferiority between MLT and SLT at 12 months in terms of absolute IOP reduction (17%) and medication reduction, with MLT producing fewer transient pressure spikes and virtually no structural damage to the trabecular meshwork [

37].

Although MLT is not traditionally considered a first-line option in advanced glaucoma, its favorable safety and tolerability profile may justify its use in carefully selected high-risk patients. When positioned within the broader surgical spectrum, MLT remains the least invasive and most conjunctiva-sparing procedure available, preserving the ocular surface for potential future interventions such as minimally invasive glaucoma surgery or filtration procedures. Its minimal recovery time, repeatability, and excellent tolerability make it an attractive option in health systems where access to surgery is limited or for patients who wish to postpone or temporarily avoid incisional operations, although it does not replace surgery when more substantial or sustained pressure lowering is required. In this regard, MLT complements both medical and surgical management, functioning as a flexible tool that can be tailored to disease severity and patient needs.

The main strengths of this study lie in its real-world design, standardized treatment parameters, and comprehensive assessment of outcomes using dual tonometry and visual function measures. The use of a uniform 360° protocol (577 nm, 300 µm, 300 ms, 15% duty cycle, 1000 mW) across all eyes ensures reproducibility and comparability with contemporary studies, while inclusion of various open-angle subtypes enhances external validity. The cohort reflects a typical clinical spectrum of glaucoma, including medicated and pseudophakic patients, demonstrating that MLT performs consistently under routine conditions. The absence of significant adverse events or IOP spikes further supports the excellent safety profile of the technique and confirms that subthreshold photostimulation can be applied safely across different pigmentary and anatomical contexts.

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The lack of a randomized control group and the observational design limit direct comparison with SLT or medical therapy. Follow-up duration varied among patients, precluding precise evaluation of long-term durability, and medication reduction was not formally quantified. Although the sample size was adequate to detect significant IOP changes, larger multicenter studies would improve statistical power and generalizability. While the primary analysis used a GEE model adjusted for age, sex, and eye laterality, no significant interactions were found between treatment effect and these covariates. However, the study was not powered to detect subtle subgroup differences, and future studies with larger samples may benefit from expanded multivariable GEE or mixed-effects models. These approaches could explore additional baseline predictors of treatment response and align with recent biostatistical guidance in ophthalmic research, where covariate-adjusted longitudinal models are increasingly recommended [

27]. Baseline IOP values already in the high teens likely attenuated the relative reduction achievable, reflecting the physiological ceiling for trabecular interventions in pretreated eyes. Finally, while structural and molecular imaging were beyond the scope of this analysis, future research integrating anterior segment OCT or aqueous cytokine profiling could clarify the mechanisms underlying the trabecular remodeling response to MLT.

Despite these limitations, the consistent efficacy, safety, and tolerability indicated here strengthen the evidence supporting MLT as a reproducible, minimally invasive option within the evolving therapeutic continuum of glaucoma management.