Indications of Clinical Application of L5 Laminar Hook for the Surgical Correction of Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

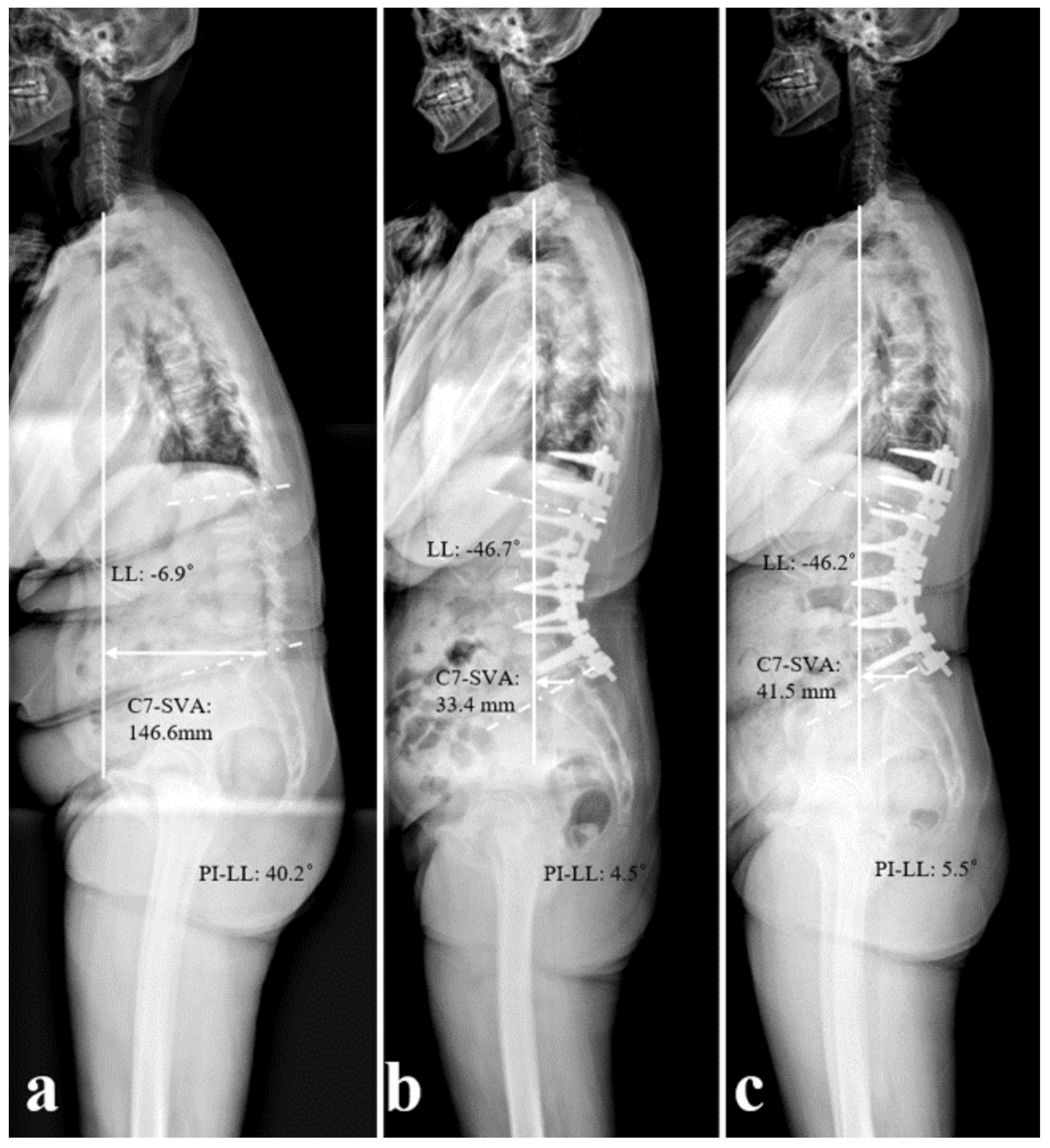

2.2. Radiographic Analysis

2.3. Disc Degeneration Assessment

2.4. Radiographic Parameters and Disc Status Measurement

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Disc Status

3.3. Sagittal Spinopelvic Parameters

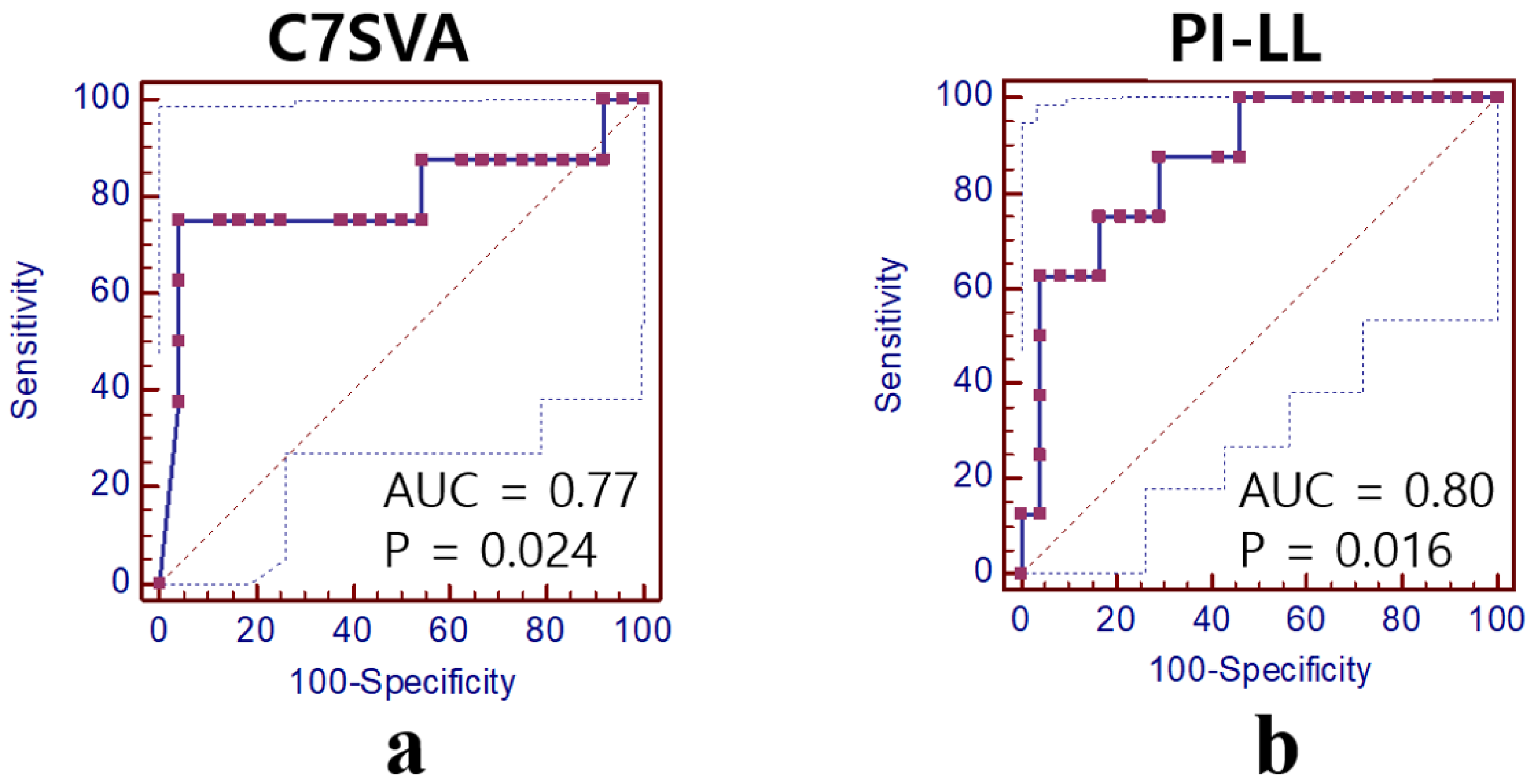

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.5. Assessment of the Reliability of Radiographic Parameters and Disc Status Measurements Using ICC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSI | Degenerative sagittal imbalance |

| C7SVA | C7 sagittal vertical axis |

| LL | Lumbar lordosis |

| PI | Pelvic incidence |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| TK | Thoracic kyphosis |

| TLK | Thoracolumbar kyphosis |

| PT | Pelvic tilt |

| SS | Sacral slope |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

References

- Edwards, C.C., 2nd; Bridwell, K.H.; Patel, A.; Rinella, A.S.; Berra, A.; Lenke, L.G. Long adult deformity fusions to L5 and the sacrum. A matched cohort analysis. Spine 2004, 29, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneichi, H.; Inami, S.; Moridaira, H.; Takeuchi, D.; Sorimachi, T.; Ueda, H.; Aoki, H.; Iimura, T. Can we stop the long fusion at L5 for selected adult spinal deformity patients with less severe disability and less complex deformity? Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 194, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margulies, J.Y.; Casar, R.S.; Caruso, S.A.; Neuwirth, M.G.; Haher, T.R. The mechanical role of laminar hook protection of pedicle screws at the caudal end vertebra. Eur. Spine J. 1997, 6, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wilke, H.J.; Kaiser, D.; Volkheimer, D.; Hackenbroch, C.; Püschel, K.; Rauschmann, M. A pedicle screw system and a lamina hook system provide similar primary and long-term stability: A biomechanical in vitro study with quasi-static and dynamic loading conditions. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2919–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, K.; Takahashi, H.E.; Uchiyama, S.; Hirano, T.; Hara, T.; Washio, T.; Sugiura, T.; Youkaichiya, M.; Ikeda, M. An experimental study of a combination method using a pedicle screw and laminar hook for the osteoporotic spine. Spine 1997, 22, 958–962; discussion 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfirrmann, C.W.; Metzdorf, A.; Zanetti, M.; Hodler, J.; Boos, N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 2001, 26, 1873–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannizzaro, D.; Anania, C.D.; De Robertis, M.; Pizzi, A.; Gionso, M.; Ballabio, C.; Ubezio, M.C.; Frigerio, G.M.; Battaglia, M.; Morenghi, E.; et al. The lumbar adjacent-level syndrome: Analysis of clinical, radiological, and surgical parameters in a large single-center series. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2023, 39, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leduc, S.; Mac-Thiong, J.M.; Maurais, G.; Jodoin, A. Posterior pedicle screw fixation with supplemental laminar hook fixation for the treatment of thoracolumbar burst fractures. Can. J. Surg. 2008, 51, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lentz, J.; Mun, F.; Suresh, K.; Groves, M.; Sponseller, P.J.J. How and When to Use Hooks to Improve Deformity Correction. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Soc. N. Am. 2021, 3, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, E.; Alkalay, R.; Vader, D.; Snyder, B.D. Preventing distal pullout of posterior spine instrumentation in thoracic hyperkyphosis: A biomechanical analysis. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2009, 22, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, T.; Dubousset, J.F.; Illés, T. Sagittal plane correction in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2002, 27, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, S.; Nagamoto, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Sugiura, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Iwasaki, M. Adjacent Segment Disease After Single Segment Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion for Degenerative Spondylolisthesis: Minimum 10 Years Follow-up. Spine 2018, 43, E1384–E1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugue, I.; Okada, S.; Masuda, M.; Ueta, T.; Maeda, T.; Shiba, K. Risk factors for adjacent segment pathology requiring additional surgery after single-level spinal fusion: Impact of pre-existing spinal stenosis demonstrated by preoperative myelography. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.J.; Suk, S.I.; Park, S.R.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.W.; Yoon, Y.H.; Won, M.H. Arthrodesis to L5 versus S1 in long instrumentation and fusion for degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhns, C.A.; Bridwell, K.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Amor, C.; Lehman, R.A.; Buchowski, J.M.; Edwards, C., 2nd; Christine, B. Thoracolumbar deformity arthrodesis stopping at L5: Fate of the L5–S1 disc, minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine 2007, 32, 2771–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ding, W. Risk factors for adjacent segment degeneration after posterior lumbar fusion surgery in treatment for degenerative lumbar disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, M.P.; Berven, S.H.; Benzel, E.C. Benzel’s Spine Surgery; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Sun, J. Comparison of long fusion terminating at L5 versus the sacrum in treating adult spinal deformity: A meta-analysis. Eur. Spine. J. 2020, 29, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group I (Hook+, n = 64) | Group II (Hook−, n = 48) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 73.5 ± 7.19 | 72.86 ± 6.20 | 0.128 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 28:4 | 20:4 | 0.269 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.05 ± 3.98 | 26.86 ± 4.67 | 0.114 |

| BMD (T-score) | −1.24 ± 1.14 | −1.03 ± 2.15 | 0.625 |

| UIV level (n, %) | 0.125 | ||

| T9 | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| T10 | 12 (18.7%) | 6 (12.5%) | |

| T11 | 28 (43.8%) | 16 (33.3%) | |

| T12 | 22 (34.4%) | 24 (50%) | |

| Preoperative diagnosis (n, %) | 0.546 | ||

| Multi-seg. Spinal stenosis with sagittal imbalance | 50 (78.1%) | 36 (75%) | |

| Multiple-level fractures | 8 (12.5%) | 6 (12.5%) | |

| Iatrogenic flatback | 4 (6.3%) | 4 (8.3%) | |

| Post-traumatic kyphosis | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (4.2%) | |

| Pelvic incidence (n, %) | 0.411 | ||

| ≤45° | 10 (15.6%) | 8 (16.6%) | |

| >45° but ≤60° | 30 (46.9%) | 20 (41.7%) | |

| >60° | 24 (37.5%) | 20 (41.7%) |

| Group I (Hook+, n = 64) | Group II (Hook−, n = 48) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degeneration Grade of L5–S1 (n, %) | |||

| Preoperative | 1.000 | ||

| Pfirrmann grade 1, 2 or 3 (healthy) | 64 (100%) | 48 (100%) | |

| Pfirrmann grade 4 or 5 (degenerated) | 0 | 0 | |

| Follow-up at 2 years | <0.001 * | ||

| Pfirrmann grade 1, 2 or 3 (healthy) | 50 (78.1%) | 12 (25.0%) | |

| Pfirrmann grade 4 or 5 (degenerated) | 14 (21.9%) | 36 (75.0%) |

| Parameter | Group I (Hook+, n = 64) | Group II (Hook−, n = 48) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 SVA (mm) | Preop. | 174.6 ± 45.5 | 52.9 ± 65.1 | 0.011 * |

| Immed. postop. | 38.1 ± 45.3 | 23.8 ± 35.4 | 0.412 | |

| 2 years postop. | 49.4 ± 33.8 | 54.5 ± 64.3 | 0.584 | |

| Change | −136.2 ± 68.6 | −29.3 ± 75.8 | 0.018 * | |

| TK (°) | Preop. | 13.8 ± 14.5 | 8.2 ± 18.5 | 0.333 |

| Immed. postop. | 24.8 ± 11.7 | 23.3 ± 14.6 | 0.611 | |

| 2 years postop. | 26.7 ± 10.8 | 27.9 ± 16.3 | 0.584 | |

| Change | 10.9 ± 9.5 | 15.1 ± 14.4 | 0.219 | |

| TLK (°) | Preop. | 16.9 ± 16.2 | 12.5. ± 14.2 | 0.398 |

| Immed. postop. | 2.6 ± 10.4 | 0.7 ± 5.7 | 0.454 | |

| 2 years postop. | 7.4 ± 12.1 | 5.3 ± 6.6 | 0.433 | |

| Change | −14.3 ± 14.9 | −16.2 ± 15.5 | 0.414 | |

| LL (°) | Preop. | −11.6 ± 19.3 | −22.8 ± 23.6 | 0.029 * |

| Immed. postop. | −52.1 ± 10.3 | −48.2 ± 17.7 | 0.299 | |

| 2 years postop. | −46.9 ± 11.2 | −43.3 ± 20.9 | 0.322 | |

| Change | −40.5 ± 15.4 | −25.4 ± 21.3 | 0.021 * | |

| PT (°) | Preop. | 26.8 ± 8.6 | 24.4 ± 9.7 | 0.428 |

| Immed. postop. | 18.6 ± 7.9 | 18.1 ± 9.9 | 0.644 | |

| 2 years postop. | 22.6 ± 8.1 | 21.4 ± 9.2 | 0.521 | |

| Change | −8.2 ± 7.8 | −6.3 ± 4.8 | 0.447 | |

| SS (°) | Preop. | 26.5 ± 10.2 | 29.1 ± 7.9 | 0.341 |

| Immed. postop. | 38.2 ± 9.3 | 34.7 ± 7.6 | 0.331 | |

| 2 years postop. | 34.1 ± 8.1 | 31.2 ± 7.2 | 0.421 | |

| Change | 7.6 ± 7.9 | 5.6 ± 5.7 | 0.457 | |

| PI-LL (°) | Preop. | 44.4 ± 17.5 | 29.1 ± 21.2 | 0.041 * |

| Immed. postop. | 3.9 ± 9.3 | 4.3 ± 6.6 | 0.551 | |

| 2 years postop. | −10.51 ± 5.5 | −15.42 ± 9.72 | 0.551 | |

| Change | −40.5 ± 15.3 | −24.8 ± 21.4 | 0.034 * |

| Group A (Preserved, n = 50) | Group B (Exacerbated, n = 14) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | 72.86 ± 6.43 | 74.13 ± 8.28 | 0.187 |

| Gender (Female/Male) | 22:3 | 6:1 | 0.245 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.11 ± 3.52 | 27.94 ± 4.39 | 0.038 * |

| BMD (T-score) | −1.25 ± 3.52 | −1.26 ± 1.20 | 0.523 |

| Preoperative diagnosis (n, %) | 0.312 | ||

| Multi-seg. Spinal stenosis with sagittal imbalance | 40 (80.0%) | 12 (85.7%) | |

| Multiple-level fractures | 6 (12.0%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| Iatrogenic flatback | 2 (4.0%) | 0 | |

| Post-traumatic kyphosis | 2 (4.0%) | 0 | |

| Preop. L5–S1 Deg. grade (n, %) | 0.891 | ||

| Pfirrmann grade 1, 2, or 3 | 50 (100%) | 14 (100%) | |

| Pfirrmann grade 4 or 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Parameter | Group A (Preserved Disc) | Group B (Exacerbated Disc) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 SVA (mm) | Preop. | 158.9 ± 94.1 | 205.8 ± 109.4 | 0.026 * |

| Immed. postop. | 34.7 ± 36.1 | 45.8 ± 60.1 | 0.312 | |

| Change | −124.2 ± 85.7 | −160.0 ± 77.8 | 0.037 * | |

| TK (°) | Preop. | 12.1 ± 9.9 | 14.7 ± 16.5 | 0.511 |

| Immed. postop. | 19.6 ± 8.2 | 27.4 ± 12.5 | 0.227 | |

| Change | 7.5 ± 8.1 | 12.7 ± 10.8 | 0.331 | |

| TLK (°) | Preop. | 14.5 ± 22.4 | 18.7 ± 15.3 | 0.317 |

| Immed. postop. | 1.4 ± 10.3 | 4.1 ± 10.9 | 0.385 | |

| Change | −13.1 ± 10.8 | −14.6 ± 9.8 | 0.554 | |

| LL (°) | Preop. | −15.1 ± 16.9 | −8.8 ± 23.1 | 0.167 |

| Immed. postop. | −53.9 ± 10.8 | −48.5 ± 8.8 | 0.221 | |

| Change | −38.8 ± 22.7 | −39.7 ± 22.7 | 0.548 | |

| PT (°) | Preop. | 28.1 ± 8.5 | 26.9 ± 9.1 | 0.531 |

| Immed. postop. | 18.3 ± 8.4 | 19.3 ± 7.5 | 0.544 | |

| Change | −10.8 ± 11.4 | −7.6 ± 7.4 | 0.362 | |

| SS (°) | Preop. | 25.4 ± 10.9 | 27.4 ± 9.1 | 0.487 |

| Immed. postop. | 37.6 ± 8.1 | 36.4 ± 11.9 | 0.514 | |

| Change | 12.2 ± 7.9 | 9.1 ± 10.8 | 0.365 | |

| PI-LL (°) | Preop. | 40.7 ± 18.1 | 51.9 ± 14.4 | 0.039 * |

| Immed. postop. | 2.2 ± 10.5 | 7.5 ± 8.1 | 0.287 | |

| Change | −38.5 ± 12.8 | −44.4 ± 10.8 | 0.044 * |

| Parameter | Cut-Off | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7SVA (cm) | 15.8 | 0.77 (0.35–0.97) | 75.0 | 95.8 | 97.0 | 79.0 |

| PI-LL (°) | 40.8 | 0.80 (0.47–0.99) | 90.5 | 70.8 | 76.0 | 88.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Kim, Y.-C.; Son, I.-S.; Kim, S.-M. Indications of Clinical Application of L5 Laminar Hook for the Surgical Correction of Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance. Medicina 2025, 61, 1963. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111963

Li X, Kim Y-C, Son I-S, Kim S-M. Indications of Clinical Application of L5 Laminar Hook for the Surgical Correction of Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):1963. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111963

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiongjie, Yong-Chan Kim, In-Seok Son, and Sung-Min Kim. 2025. "Indications of Clinical Application of L5 Laminar Hook for the Surgical Correction of Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance" Medicina 61, no. 11: 1963. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111963

APA StyleLi, X., Kim, Y.-C., Son, I.-S., & Kim, S.-M. (2025). Indications of Clinical Application of L5 Laminar Hook for the Surgical Correction of Degenerative Sagittal Imbalance. Medicina, 61(11), 1963. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111963