1. Introduction

Colon cancer is the third most diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

1]. In 2022, approximately 1.9 million new cases and 0.9 million deaths were reported, accounting for 9.6% of all cancer cases and 9.3% of cancer deaths globally [

1,

2]. By 2040, new cases and deaths are projected to rise to 3.2 million and 1.6 million, respectively, reflecting increases of 63% and 73.4% compared to 2020 [

1].

Colon cancer originates from the hyperproliferation of mucosal epithelial cells, forming polyps or adenomas; about 10% of these progress to cancer as they grow larger. Adenocarcinoma, the invasive form, constitutes 96% of colon cancer cases [

3]. While surgical resection is the primary treatment, recurrence occurs in 30–40% of cases, with 40–50% of recurrences appearing within the first few years after surgery [

4]. Radiotherapy and chemotherapy, though effective against cancer cells, also damage healthy tissues, and multidrug resistance further reduces treatment efficacy, often leading to failure [

5]. These challenges underscore the urgent need for novel colon cancer treatment strategies. One promising direction involves the exploration of natural compounds that selectively target cancer cell metabolism, particularly mitochondrial pathways, which are often dysregulated in cancer cells.

Fireweed (

Chamerion angustifolium L.) is included in a European Medicines Agency (EMA) monograph stating that it can be used to relieve lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia [

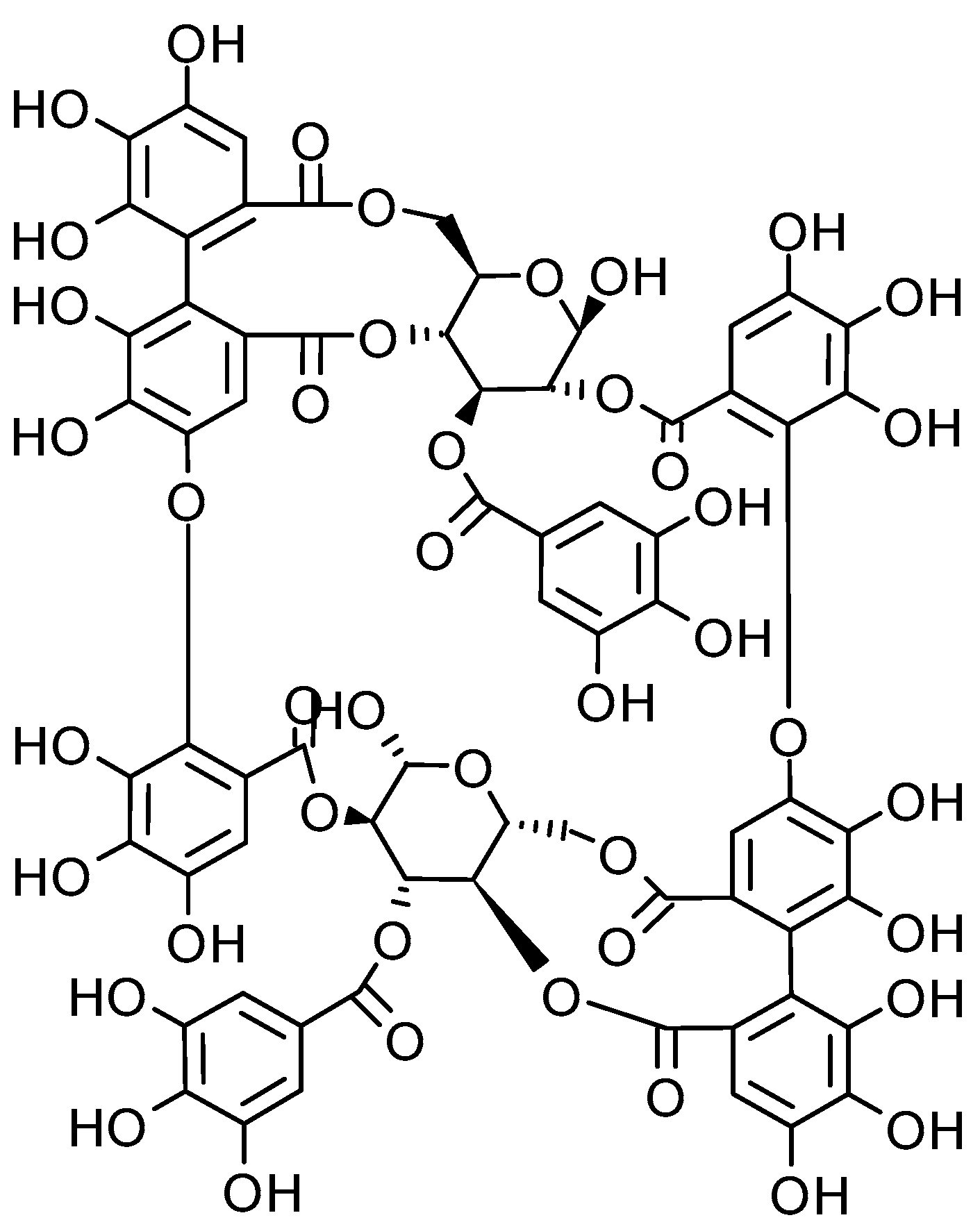

6]. Fireweed contains abundant secondary metabolites, particularly polyphenolic compounds such as tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. The diversity and abundance of these bioactives suggest that fireweed may exert pleiotropic effects at the cellular level, impacting several molecular pathways simultaneously. The tannin oenothein B (

Figure 1) is believed to be the primary compound responsible for its anti-androgenic, anti-proliferative, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties [

7,

8]. Studies show that fireweed extracts exhibit anti-proliferative effects in both normal and cancer cells, including LNCaP (androgen-dependent), PZ-HPV-7 (androgen-independent), 1321N1 (astrocytoma), and HMEC (normal mammary cells) [

9]. In LNCaP cells, fireweed extracts activated the apoptotic cascade by disrupting mitochondrial membranes [

10]. Additionally, oenothein B has been shown to significantly reduce the growth of various cancer cell lines, such as KB (oral epidermoid), HeLa (cervical), DU-145 (prostate carcinoma), Hep-3B (hepatocellular), and HL-60 (promyelocytic leukemia), while exhibiting lower cytotoxicity to normal cells (WISH) [

11]. These findings underscore fireweed’s potential as an anticancer agent, particularly for colon cancer, due to its ability to inhibit cancer cell growth with minimal impact on normal cells [

10,

11]. However, the precise mechanisms by which fireweed and its key constituents affect cellular targets, particularly mitochondria, remain insufficiently explored.

Despite these known benefits, little is understood about how fermentation—a process commonly used in traditional herbal medicine—modulates fireweed’s bioactive compounds and enhances its therapeutic effects. Fermentation, particularly solid-phase fermentation, is widely used in the food industry to modify plant properties such as smell, taste, and color and to enhance substance extraction [

12]. This creates functional foods and beverages beneficial for health [

13], which are mild in action and difficult to overdose [

14]. Tea made from fermented fireweed leaves is an example of solid-phase fermentation improving its composition [

15].

Solid-phase fermentation is carried out without adding water; instead, crushed and pressed leaves promote enzymatic degradation. Lasting 1–3 days, this process induces both intracellular biochemical changes and strong microbial activity. Enzymes produced by lactic acid bacteria, yeasts, and plant enzymes such as polyphenol oxidase break down macromolecules (proteins, lipids, polysaccharides) into low-molecular-weight compounds and secondary metabolites. Fermentation—whether aerobic or anaerobic—alters the phenolic profile by degrading complex molecules and enhancing compound bioavailability. In fireweed, solid-phase fermentation markedly affects polyphenol, flavonoid, and oenothein B content; anaerobic conditions increase these compounds the most, whereas aerobic fermentation yields an extract with the highest antioxidant activity [

15].

All living cells, whether healthy or cancerous, require energy to function. This energy is primarily produced through glycolysis in the cytoplasm and/or oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. Currently, there is a lot of research on fireweed’s effect on cancer cell proliferation; however, there is little data on its effect on cancer cell mitochondrial function. The development of natural-origin therapeutic agents that modulate the mitochondrial function of cancer cells as well as cancer cell viability is crucial, as it can open new avenues for more effective cancer treatments and improve patient survival outcomes. Alternatively, it could be used for cancer prevention, offering a proactive approach to reducing the risk of cancer development. There is a limited number of studies investigating the effects of fireweed extract on mitochondrial function in colon cancer cells. Despite the promising preliminary evidence, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding the specific effects of fireweed on mitochondrial energy metabolism in cancer cells, especially under different processing conditions, such as fermentation.

Given the increasing interest in the biological properties of fireweed and the potential of fermentation to boost bioactivity, this study aims to investigate the effects of unfermented and fermented fireweed leaf extracts, and their main component oenothein B, on the viability and mitochondrial function of Caco-2 colon cancer cells. Specifically, we seek to investigate whether fermentation alters the phytochemical composition of fireweed and its subsequent impact on cancer cell viability and mitochondrial function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Ethylene glycol-bis-(b-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), MgCl2, lactobionic acid, taurine, KH2PO4, Tris were obtained from “Sigma-Aldrich” (St. Louis, MO, USA). Sucrose and HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) were obtained from “Carl Roth GmbH” (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Glutamic acid, malic acid, digitonin, adenosine-5‘-diphosphate sodium salt (ADP), succinic acid, cytochrome c from bovine heart, carboxytractyloside potassium salt, 2,4-dinitrophenol were obtained from “Sigma-Aldrich” (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Oenothein B was obtained from “Sigma-Aldrich” (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Plant Materials

The plant material was collected from Giedres Nacevicienes organic farm in 2023, located in Safarkos village, Jonava district, Lithuania. A section on a farm was left for fireweed to grow naturally by itself. The collected raw material was separated into the following 3 samples: unfermented, fermented for 24 h, and 48 h. The solid-phase fermentation was performed under aerobic conditions.

2.3. Solid-Phase Fermentation Process

Using specialized plastic blades, fresh fireweed leaves were chopped for the solid-phase fermentation process. The resultant raw material was then split into three samples. The fermented ready bulk was firmly packed into glass jars and sealed with an air-passing lid. For 24 and 48 h, the fermentation process was conducted in the chamber at 30 °C. After fermentation, the raw materials were lyophilized in a ZIRBUS sublimation dryer 3 × 4 × 5 (ZIRBUS Technology, Bad Grund, Germany) and frozen at −35 °C. For further analysis, the lyophilized leaves were ground into a powder using a Grindomix GM 200 laboratory mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany). The plant material powder was provided by the VMU Agriculture Academy, Department of Plant Biology and Food Sciences, scientific group.

2.4. Caco-2 Cell Line and Growing Conditions

Colorectal adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line Caco-2 was obtained from American Type Cell Culture (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in Ham’s F-12 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies Limited, Paisley, UK) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco Life Technologies Limited, Paisley, UK) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (Gibco Life Technologies Limited, Paisley, UK). Cells were cultivated in monolayers in sterile flasks/plates in an incubator at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidity.

2.5. Fireweed Extract Preparation

Aqueous fireweed extracts were prepared from the provided plant material powder and non-sterile F-12 cell medium (concentration 25 mg/mL). The prepared solution was left at room temperature for 1 h. Afterwards, the solution was centrifuged, and the obtained supernatant was filtered using a 0.22 µm filter. The obtained extract was diluted to reach the required concentrations for cell treatment.

2.6. Oenothein B Preparation

A stock solution of oenothein B was prepared with non-sterile F-12 cell medium (concentration 1 mg/mL or 637 µM). The obtained solution was filtered using a 0.22 µm filter. The stock solution was diluted to reach the required concentrations for cell treatment.

2.7. Fireweed Extract Phytochemical Analysis Using HPLC

The identification and quantitative analysis of the active compounds were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). A Waters Alliance system, a 2695 chromatographic system with a 2998 diode-array detector, and an ACE 5 C18 chromatography column (250 × 4.6 mm) were used. Data was processed by Empower 3 Chromatography Data Software (version 3.9.0) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The eluent system consists of 100% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, injection volume 10 µL, column temperature 25 °C, mobile phase flow rate 1 mL/min. The active compounds in the sample were identified by the retention time of the analytes and spectral data in the working range 200–400 nm.

2.8. Fireweed Extract and Oenothein B Treatment of Cells and IC50 Measurement

Cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates (1.2 × 104 cells/well) and incubated for 24 h, maintaining the above-described conditions. After incubation, the cells were treated with varying concentrations of aqueous fireweed extract (0.5–3 mg/mL) and oenothein B (0.01–0.1 mg/mL) to test the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). A portion of the cancer cells remained untreated and were used as a control group. Cells were incubated for 48 h in the same conditions. MTT assay was used to determine IC50 for each fireweed extract. No less than 3 replicates of the experiment were carried out. The IC50 was calculated using Quest Graph IC50 Calculator (AAT Bioquest, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.9. MTT Metabolic Activity Assay

Cell viability was assessed by MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) assay. After treatment, the old growth medium was removed and new medium with MTT was added (MTT concentration of 0.5 mg/mL). The cells were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the medium with MTT was removed, and the remaining formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µL DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) (Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) by agitation in the spectrophotometer for 90 s. The absorbance was measured with the spectrophotometer (The Sunrise (Software v7.1), Tecan, Grodig, Austria) at a wavelength of 570/620 nm. Colorimetric absorption values were compared to the untreated control group.

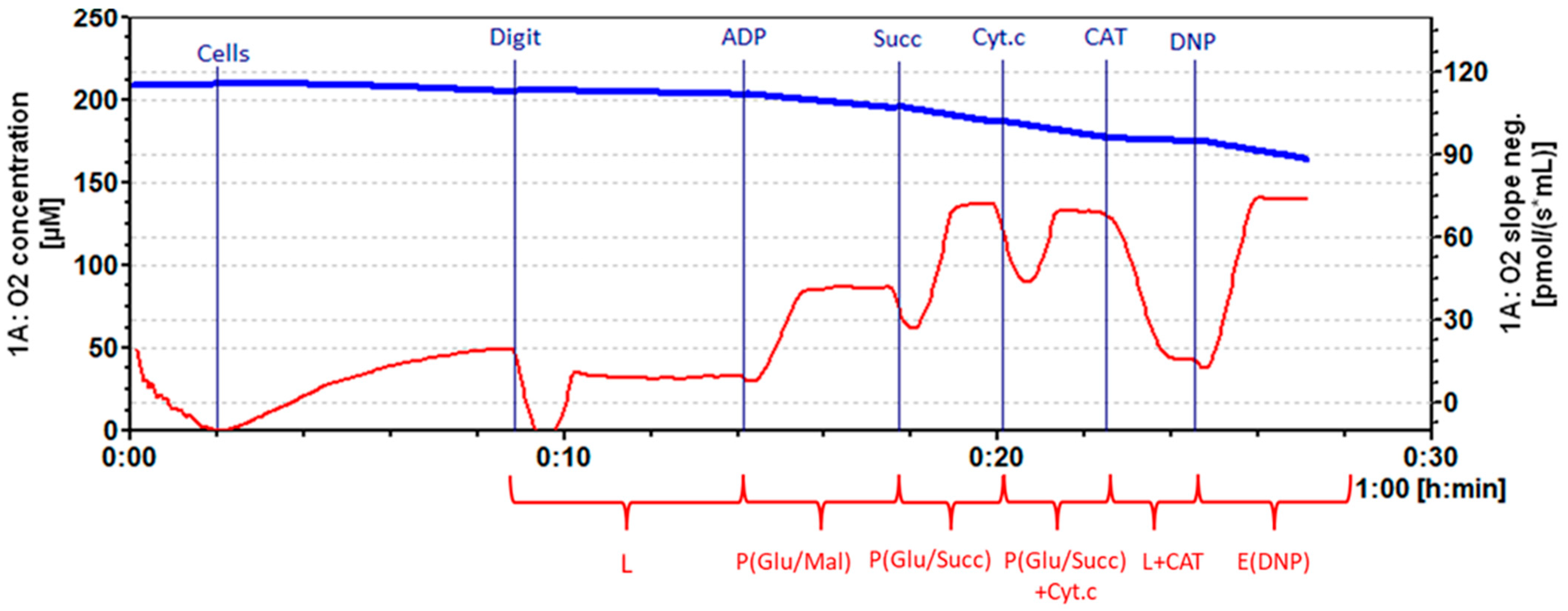

2.10. Measurement of Mitochondrial Function in Cancer Cells

Caco-2 cells were treated with a determined IC

50 of fireweed extracts and oenothein B for 48 h. A portion of the cancer cells was left untreated and used as a control group. Mitochondrial respiration (oxygen consumption) rate was recorded by high–resolution respirometry system Oxygraph-2k (OROBOROS Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) at 37 °C in the MiR06 medium (0.5 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl

2, 60 mM lactobionate, 20 mM Taurine, 10 mM KH

2PO

4, 20 mM HEPES, 110 mM sucrose (pH 7.1 at 30 °C)). Digitonin (16 µg/mL) was added and incubated for 5 min to permeabilize the cell membrane. Mitochondrial respiration rate in Leak state (L) was recorded in the medium with cells and mitochondrial Complex 1 substrate (5 mM glutamate + 2 mM malate). Maximal oxidative phosphorylation rate (P(Glu/Mal)) in the presence of Complex 1 substrates was determined by adding 1 mM ADP. Complex 2 substrate succinate (12 mM) was used to achieve maximal mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (P(Glu/Succ)) in the presence of Complex 1 and II substrates. The effect of cytochrome c on respiration rate (to identify mitochondrial outer membrane permeability) was determined by adding 32 μM cytochrome c (P(Glu/Succ) + Cyt.c). 0.75 µM of carboxyatractyloside (CAT) was added to assess the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane (L + CAT). To determine the respiration chain effectiveness, 0.3 mM of 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) was added to the medium (E(DNP)). The respiratory control index (RCI) for glutamate/malate was calculated as the ratio between P(Glu/Mal)/L respiration rate. RCI for succinate was calculated from the ratio P(Glu/Succ) + Cyt.c/L + CAT. Cytochrome c effect was calculated as the ratio P(Glu/Succ) + Cyt.c)/P(Glu/Succ). Datlab 7 software (version 7.4.0.4) (OROBOROS Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) was used for real-time data acquisition and data analysis. Oxygen consumption was related to cell numbers (pmol/s/0.7 mLn cells) (

Figure 2).

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.1.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The data are presented as mean ± SD of three or more independent experiments. The level of statistical significance was set as p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Interest in fireweed as a medicinal plant has increased in its pharmacological properties and potential anticancer effects. Studies show that fireweed extract reduces cancer cell proliferation with minimal effects on healthy cells [

10,

11]. Since mitochondria are central to cancer cell metabolism, understanding their response to fireweed extract is crucial, though data on its impact is limited. Moreover, little research exists on how fermentation affects the biological properties of fireweed extract, despite its common use in traditional medicine. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of fireweed extract and its main component, oenothein B, on Caco-2 colon cancer cell viability and mitochondrial function, and assess whether fermentation alters these effects. The increasing burden of treatment resistance and relapses in colon cancer therapy has prompted a search for novel agents that selectively target cancer cell metabolism without harming healthy cells.

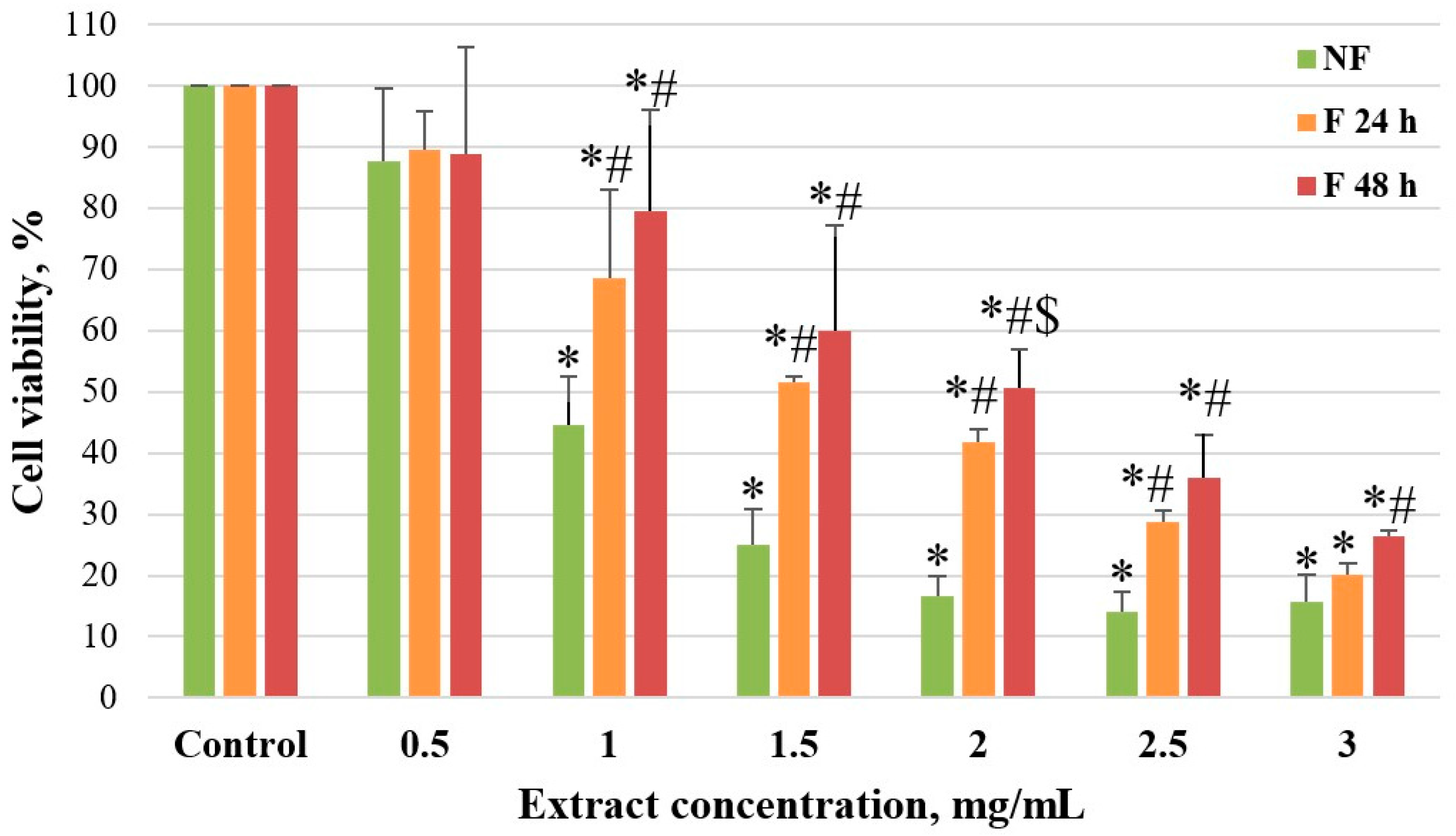

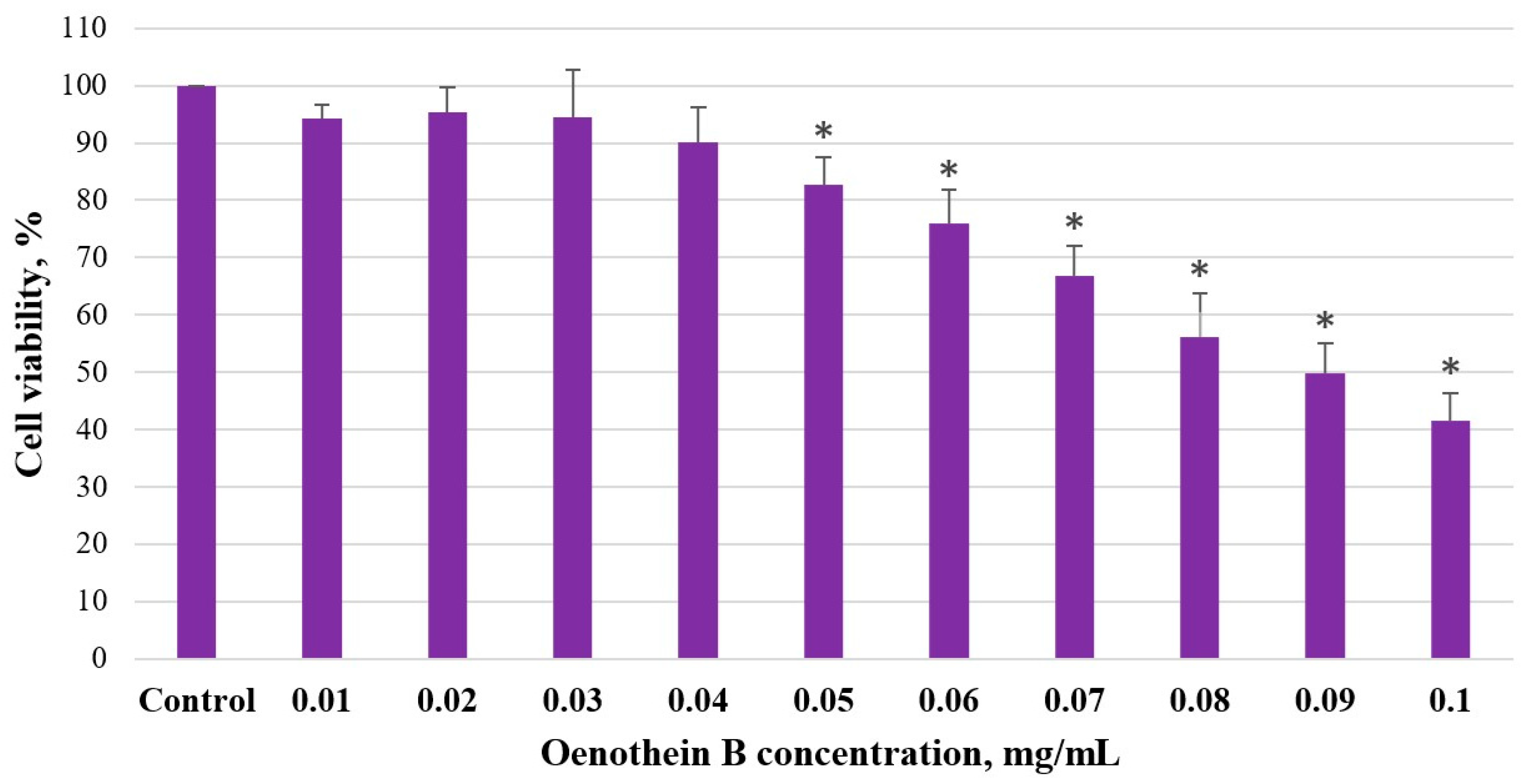

Our study showed that both unfermented and fermented fireweed leaf extracts inhibited Caco-2 colon cancer cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner, with the strongest effect observed for the unfermented extract (84% reduction at 3 mg/mL; IC50 0.843 mg/mL). The greater cytotoxicity of the unfermented extract may be related to its higher polyphenol and oenothein B content. Oenothein B alone also reduced cell viability (58% at 0.1 mg/mL; IC50 = 0.09 mg/mL (57 µM)), but its concentration in the unfermented extract (≈0.02 mg/mL) was too low to explain the full effect. This suggests that other phytochemicals in the extract may act synergistically, contributing to its stronger overall anticancer activity.

M. Perużyńska et al. [

16] evaluated the antiproliferative effects of ethanolic fireweed extract on normal human fibroblasts (HDF) and various cancer cell lines as follows: melanoma (A375), breast (MCF7), colon (HT-29), lung (A549), and liver (HepG2). HT-29 cells were three times more sensitive than HDF and five times more sensitive than HepG2 and A549, suggesting selectivity for specific cancer types.

M. Stolarczyk et al. [

17] showed that aqueous fireweed extracts strongly inhibited prostate cancer (LNCaP) cell growth (IC

50 ≈ 35 µg/mL), supporting its traditional urogenital use. Kowalik et al. [

18] found that digested extracts reduced HT-29 cell proliferation to 27% at 250 µg/mL after 96 h, while stimulating normal CCD 841 CoTr cells by 128%. Another study [

19] reported that unfermented extract (3 mg/mL) decreased Caco-2 cell viability by 91%, and fermented extract by 75% (IC

50 0.81 mg/mL and 1.18 mg/mL, respectively). Our results are consistent with these findings but extend them by using aerobic fermentation for 24–48 h, instead of 72 h anaerobic conditions, thus reflecting more traditional, food-compatible processing.

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a crucial role in cancer metabolism, and the observed disruption of oxidative phosphorylation indicates that fireweed extracts interfere with energy production essential for cancer cell survival. Inhibition of Complex 1 and 2-driven respiration led to reduced ATP synthesis and mitochondrial stress, promoting cell death. Fireweed extracts from both unfermented and fermented leaves markedly decreased in mitochondrial respiration (up to 67% with glutamate/malate and 61% with succinate), as well as oxidative phosphorylation and respiratory control indexes (by 41–56%), indicating impaired mitochondrial efficiency. Uncoupled respiration also declined by 51–63% (p < 0.05). Although minor mitochondrial membrane damage was observed, only small but significant changes in cytochrome c release were detected (6% in NF and 3% in F 24 h), suggesting slight outer membrane permeability differences between extracts.

Our study demonstrated that oenothein B, a key compound in fireweed, altered mitochondrial function mainly by increasing inner mitochondrial membrane permeability. It elevated leak respiration by 34% (L) and 73% (L + CAT) while moderately reducing oxidative phosphorylation by 24% and lowering the respiratory control index by ~45% (p < 0.05). Compared with oenothein B, fireweed extracts significantly reduced mitochondrial respiration (by 39–61%), oxidative phosphorylation (by 38–58%), and uncoupled respiration (by 49–61%), indicating a stronger inhibitory effect on mitochondrial activity. In contrast, oenothein B caused greater inner membrane damage, as reflected by higher leak respiration rates. No significant differences were observed in cytochrome c effect or respiratory control index between the treatments.

The fact that practically no statistically significant differences were observed between the fermented and unfermented groups indicates that aqueous fireweed extract effectively suppresses mitochondrial functions in Caco-2 cells, regardless of whether it is derived from fermented or unfermented leaves. The minimal difference in the effect between unfermented and fermented groups suggests that fermentation did not substantially alter the extract’s impact on mitochondrial function.

Comparisons between fireweed-treated groups and oenothein B-treated groups reveal that oenothein B on its own has a significantly weaker effect. This indicates that the phytochemical compounds detected in fireweed extract may have a synergistic effect that strengthens the inhibition of Caco-2 cell mitochondrial function.

In a previous study [

19], researchers examined the mitochondrial response of Caco-2 colon cancer cells to aqueous fireweed leaf extract in two forms, both unfermented and fermented, for 72 h under anaerobic conditions. Oxidative respiration rate P(Glu/Mal) decreased by 52% (unfermented) and 40% (fermented), while P(Glu/Succ) was reduced by 35% and 27%. An increase in leak respiration rate (L + CAT) indicated inner mitochondrial membrane damage, with a slight increase in cytochrome c effect in the unfermented group, suggesting outer mitochondrial membrane damage. Both extracts similarly reduced respiratory control indexes (RCI) by 52–56% with glutamate/malate and succinate as substrates. Our findings show a slightly greater decrease in oxidative phosphorylation and RCI, but the trend remains consistent; unfermented extract exerts a stronger effect than fermented. This is the only study available in comparison with our results. Based on these findings, further investigation into the effects of fireweed extract on cancer cell mitochondrial function is necessary, as it has the potential to become a promising treatment option for colon cancer.

M. Lasinskas et al. [

20] analyzed the phytochemical composition of fireweed collected from the same source and prepared under identical conditions as in our study. The methanolic extract of fireweed leaves analyzed by HPLC showed a 21% and 34% reduction in total polyphenols after 24 h and 48 h of aerobic fermentation. Oenothein B content slightly increased after 24 h but returned to baseline after 48 h, while phenolic acids decreased up to 47%, and flavonoids rose modestly (2–12%). In aqueous fireweed extracts investigated by us, oenothein B decreased more markedly—by 65% after 24 h and 83% after 48 h—correlating with the reduced cytotoxic effect on Caco-2 cells, as the unfermented extract with the highest oenothein B level showed the strongest antiproliferative activity.

Galambosi et al. [

21] studied the impact of fermentation on compounds detected in fireweed. Fireweed leaves collected in 2012 and 2013 were aerobically fermented for ~44 h at 28 °C, 35 °C, and 40°. Total tannins decreased by 31–44%, flavonoids by 14–24%, hyperoside by 51–68%, and oenothein B by 50–71%. These findings highlight the need for further research into the effects of fermentation on fireweed’s bioactive profiles and its therapeutic potential in cancer treatment.

Overall, our results suggest that aqueous fireweed extract disrupts mitochondrial function and reduces colon cancer (Caco-2) cell viability through the combined actions of multiple phytochemicals. The fermentation process alters this composition but does not fundamentally change the extract’s effect on mitochondrial activity. Comparisons with oenothein B alone suggest only a partial effect on Caco-2 cell viability and mitochondrial function, supporting the hypothesis of a synergistic interaction among the constituents of fireweed extract.

The next objective is to investigate the detailed mechanism of action of the non-fermented fireweed leaf extract on Caco-2 cancer cells and to assess the potential synergistic interactions among its active compounds, as this represents a promising natural approach with anticancer potential.