Manual Therapy of Dysphagia in a Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

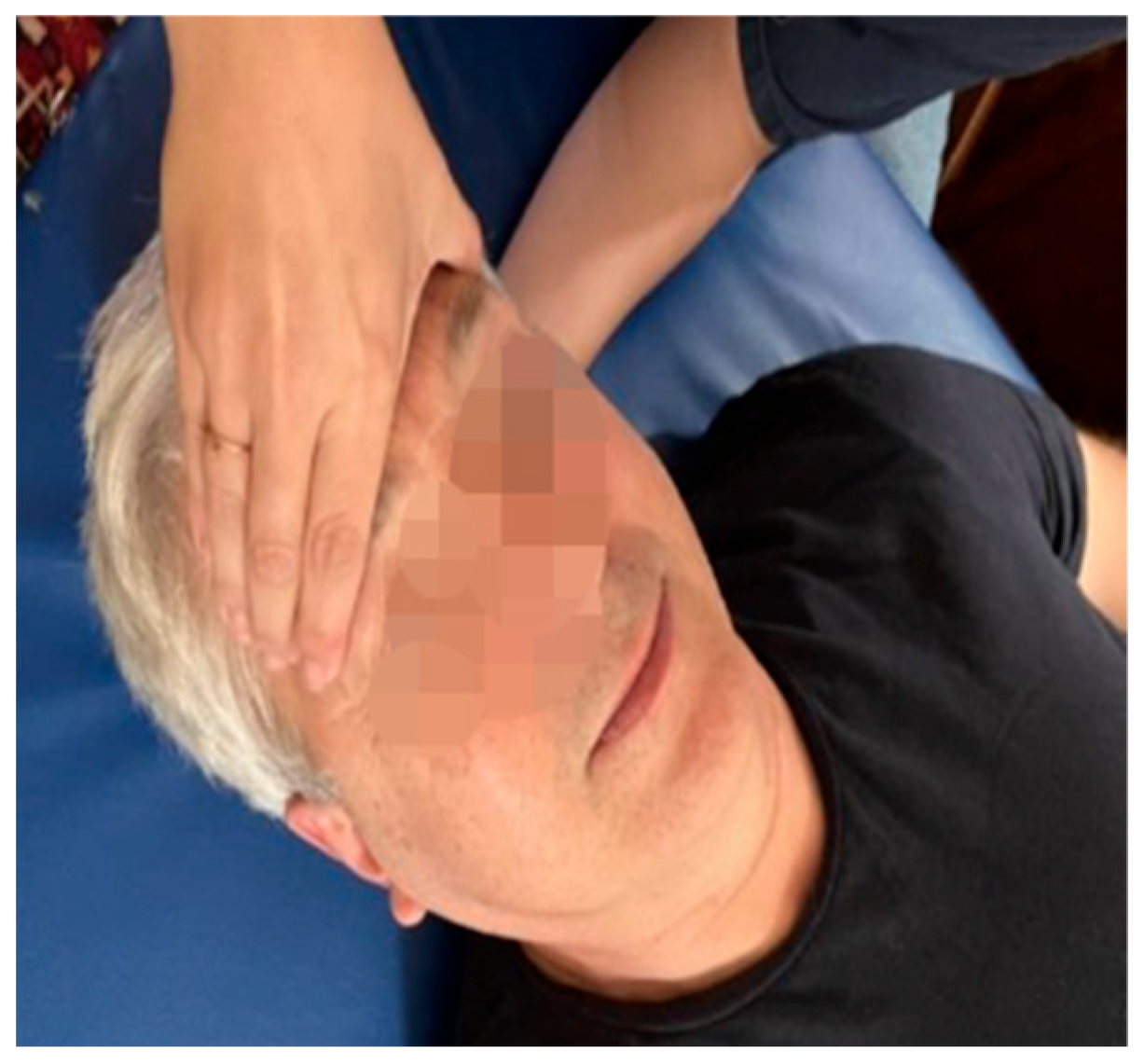

Detailed Case Presentation

- Grade 0—No SD: symmetric motion;

- Grade 1—Mild SD: asymmetric motion;

- Grade 2—Moderate SD: asymmetric variability of motion in the NZ combined with altered tissue texture or tenderness;

2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boylan, K. Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 807–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, B.; Horton, D.K.; Mitsumoto, H. Potential Environmental Factors in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Su, F.C.; Callaghan, B.C.; Goutman, S.A.; Batterman, S.A.; Feldman, E.L. Environmental risk factors and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): A case-control study of ALS in Michigan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, C.; Aydogdu, I.; Yüceyar, N.; Kiylioglu, N.; Tarlaci, S.; Uludag, B. Pathophysiological mechanisms of oropharyngeal dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2000, 123 Pt 1, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.J.; Nelson, J.; Wong, J.B.; Kent, D.M. The cumulative incidence of dysphagia and dysphagia-free survival in persons diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2021, 64, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Andersen, P.M.; Abrahams, S.; Borasio, G.D.; de Carvalho, M.; Chio, A.; Van Damme, P.; Hardiman, O.; Kollewe, K.; Morrison, K.E.; et al. EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS)—Revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012, 19, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, L. Linee Guida sulla Disfagia (FLI e SIFEL). In Proceedings of the SIMFER, Turin, Italy, 17 May 2009; Available online: https://www.simfer.it/linee-guida-sulla-disfagia-fli-e-sifel/ (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Higo, R.; Tayama, N.; Nito, T. Longitudinal analysis of progression of dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Auris Nasus Larynx 2004, 31, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, S.; Hendricks, M.; Kollewe, K.; Zapf, A.; Dengler, R.; Silani, V.; Petri, S. Weight loss, dysphagia and supplement intake in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): Impact on quality of life and therapeutic options. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiani, A.; Tremolizzo, L.; Della Valentina, A.; Mapelli, L.; Sosio, S.; Milano, V.; Bianchi, M.; Badi, F.; Lavazza, C.; Grandini, M.; et al. Osteopathic Manual Treatment for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Feasibility Pilot Study. Open Neurol. J. 2016, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.R.; Giantinoto, S.; D’Agate, D.; Areman, R.D.; Fazzini, E.A.; Dowling, D.; Bosak, A. Standard osteopathic manipulative treatment acutely improves gait performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 1999, 99, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Martinez, S.; Wells, M.R.; Capobianco, J.D. A retrospective study of cranial strain patterns in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2002, 102, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osteopathic International Alliance. Osteopathy and Osteopathic Medicine: A Global View of Practice, Patients, Education and the Contribution to Healthcare Delivery, 1st ed.; Osteopathic International Alliance (OIA): Chicago, ON, USA, 2013; Available online: https://oialliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/OIA-Stage-2-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. Benchmarks for Training in Traditional /Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Benchmarks for Training in Osteopathy, 1st ed.; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241599665 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Bergna, A.; Vismara, L.; Parravicini, G.; Dal Farra, F. A new perspective for Somatic Dysfunction in Osteopathy: The Variability Model. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, L.; Bergna, A.; Tarantino, A.G.; Farra, F.D.; Buffone, F.; Vendramin, D.; Cimolin, V.; Cerfoglio, S.; Pradotto, L.G.; Mauro, A. Reliability and Validity of the Variability Model Testing Procedure for Somatic Dysfunction Assessment: A Comparison with Gait Analysis Parameters in Healthy Subjects. Healthcare 2024, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertekin, C.; Aydogdu, I. Neurophysiology of swallowing. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 2226–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitalier, F.; Fanous, A.; Aviv, J.; Bassiouny, S.; Desuter, G.; Nerurkar, N.; Postma, G.; Crevier-Buchman, L. International consensus (ICON) on assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2018, 135, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audag, N.; Goubau, C.; Toussaint, M.; Reychler, G. Screening and evaluation tools of dysphagia in adults with neuromuscular diseases: A systematic review. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2019, 10, 2040622318821622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etges, C.L.; Scheeren, B.; Gomes, E.; Barbosa Lde, R. Screening tools for dysphagia: A systematic review. Codas 2014, 26, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertscher, B.; Speyer, R.; Palmieri, M.; Plant, C. Bedside screening to detect oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with neurological disorders: An updated systematic review. Dysphagia 2014, 29, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bours, G.J.; Speyer, R.; Lemmens, J.; Limburg, M.; de Wit, R. Bedside screening tests vs. videofluoroscopy or fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing to detect dysphagia in patients with neurological disorders: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, R.; Bretón, I.; Cereda, E.; Desport, J.C.; Dziewas, R.; Genton, L.; Gomes, F.; Jesus, P.; Leischker, A.; Muscaritoli, M.; et al. ESPEN guideline clinical nutrition in neurology. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 354–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, M.D.C.; Coutinho, K.M.D.; Vale, S.H.L.; Medeiros, G.C.B.S.; Piuvezam, G.; Leite-Lais, L.; Brandao-Neto, J. Nutritional therapy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias Vilaça, A.; Reis, A.M.; Vidal, I.M. The anatomical compartments and their connections as demonstrated by ectopic air. Insights Imaging 2013, 4, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, M. The fascia of the limbs and back—A review. J. Anat. 2009, 214, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, B.; Zanier, E. Understanding Fibroblasts in Order to Comprehend the Osteopathic Treatment of the Fascia. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 860934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piron, A. Techniques Ostéopathiques Appliquées à la Phoniatrie: Biomécanique Fonctionnelle et Normalisation du Larynx, 2nd ed.; Symétrie: Lyon, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, M.; Oliveira, A.B.; Nascimento, O.J.; Reis, C.H.M.; Leite, M.A.A.; De Souza, J.A.; Pupe, C.; De Souza, O.G.; Bastos, V.H.; De Freitas, M.R.; et al. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: New Perpectives and Update. Neurol. Int. 2015, 7, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fascial system | Dysfunctions affecting the middle and deep cervical fascia |

| Visceral system | Esophageal and pharyngeal dysfunctions |

| Craniosacral system | Compressed sphenobasilar synchondrosis Occiput-mastoid suture dysfunction |

| Musculoskeletal system | Atlo-occipital joint dysfunction Posterior hyoid bone dysfunction |

| STAGE | GOALS | TECHNIQUES | FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–4 |

|

| Once per week for 45 min |

| Weeks 5–8 |

|

| Once per week for 45 min |

| OUTCOME | PRE-TREATMENT (Before the 1st OMT Session) | POST-TREATMENT (After the 8th OMT Session) |

|---|---|---|

| Strand Scale and Swallowing tests | Slowed chewing movements and delayed gag reflex | Chewing movements suitable for chewing solid foods Slight tendency to fall pre-swallowing with liquid bolus taken with free oral cavity |

| DYALS | Difficulty swallowing liquid foods Cough when swallowing solid foods and liquids Need to drink in several sips | Cough present occasionally with fluid intake There is no need to drink in small sips |

| ALSFRS-R | 45/48 | 45/48 |

| ALSAQ-40 | Swallowing: 41.6, sometimes problematic Communication: 53.5, sometimes problematic. Emotional aspect: 24, rarely problematic | Swallowing: 25, rarely problematic Communication: 59, problems sometimes Emotional aspect: 15, no problem |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Marchi, I.; Buffone, F.; Mauro, A.; Bruini, I.; Vismara, L. Manual Therapy of Dysphagia in a Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Case Report. Medicina 2024, 60, 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060845

De Marchi I, Buffone F, Mauro A, Bruini I, Vismara L. Manual Therapy of Dysphagia in a Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Case Report. Medicina. 2024; 60(6):845. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060845

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Marchi, Ilaria, Francesca Buffone, Alessandro Mauro, Irene Bruini, and Luca Vismara. 2024. "Manual Therapy of Dysphagia in a Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Case Report" Medicina 60, no. 6: 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060845

APA StyleDe Marchi, I., Buffone, F., Mauro, A., Bruini, I., & Vismara, L. (2024). Manual Therapy of Dysphagia in a Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Case Report. Medicina, 60(6), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060845