A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of Cannabis Suppositories and Online Mindful Compassion for Improving Sexual Function Among Women Following Gynaecological Cancer Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

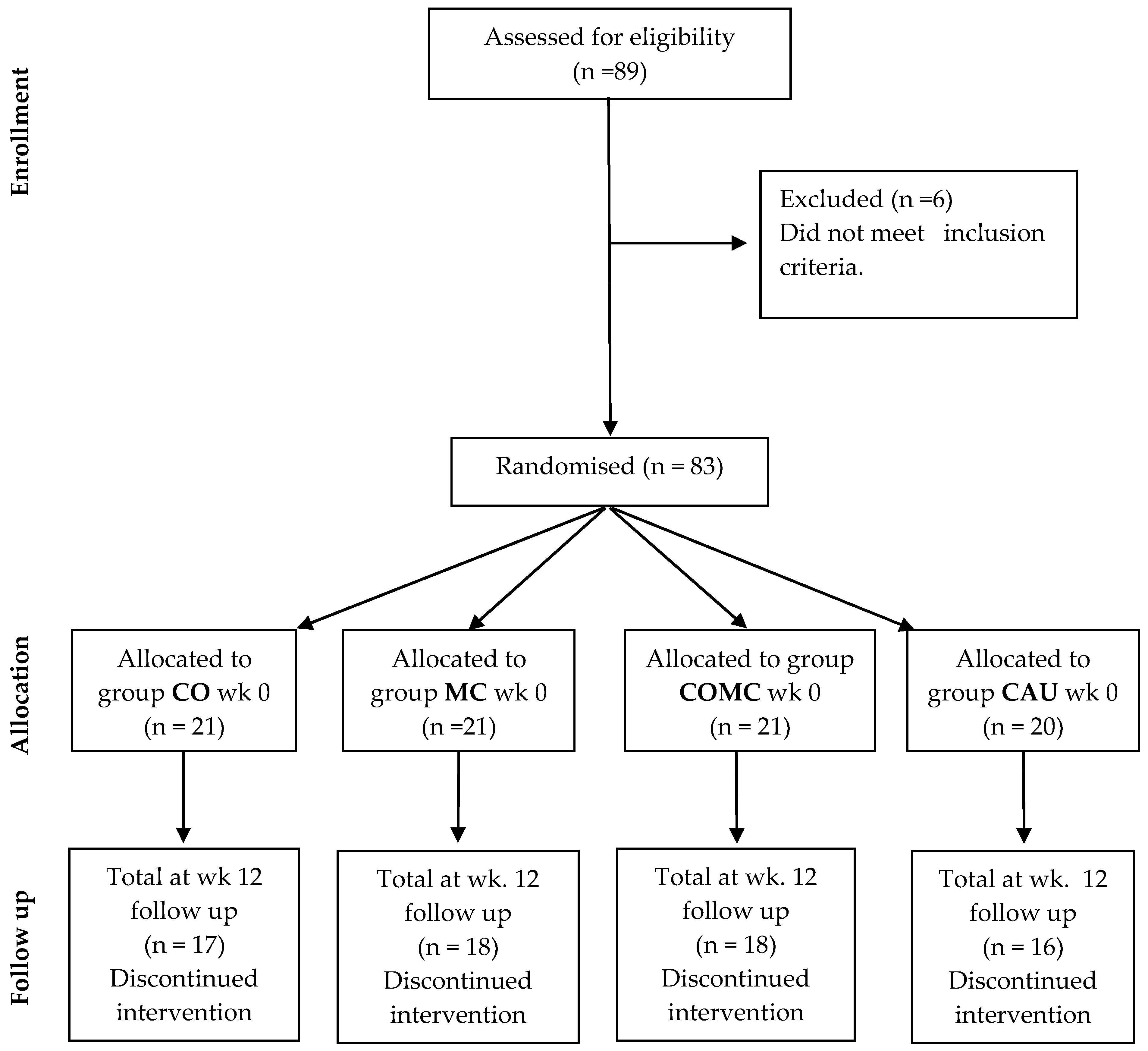

- (1)

- Cannabis-only group (CO).

- (2)

- Mindful compassion group (MC).

- (3)

- Cannabis suppositories and mindful compassion group adjuncts (COMC).

- (4)

- Care as usual (CAU/control group/not using cannabis suppositories or engaging in mindful compassion).

- There would be a significant effect of time on sexual self-efficacy, mindful compassion, sexual functioning, well-being and QOL for the CO, MC and COMC groups.

- There would be no significant effect of time on sexual self-efficacy, mindful compassion, sexual functioning, well-being and QOL in the CAU group.

- Levels of sexual functioning and sexual pain would vary between CBD and THC suppositories in the MC and COMC groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.1.1. Study 1

2.1.2. Study 2

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Participants should be at least six months or more post-cancer treatment (excluding hormone treatment).

- If applicable, each participant had been using cannabis (THC, CBD, THC/CBD adjunct) suppositories for at least one month.

- Participants should be registered with a general practitioner (GP)

- Sexual functioning involving vaginal sex was satisfactory before cancer diagnosis (acquired).

- Participants were attempting sexual intimacy.

- Participants were aged 18 years or older.

- Participants were fluent in reading and writing English (as this is a clinical trial, we wanted to ensure that participants fully understood what was expected of them).

- A patient health questionnaire-PHQ-9 score of between 0 and 9 [25].

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Applicants were currently receiving cancer treatment, such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

- Applicants were not registered with a GP.

- Applicants were sexually abstinent.

- Applicants were aged under 18 years old.

- Sexual functioning involved anal sex

- Applicants showed difficulties in reading and writing English.

- Applicants had lifelong sexual function difficulties.

- Applicants had a PHQ-9 score range between 10 and 27.

2.3. Mindful Compassion Intervention

2.4. Self-Report Measures

2.4.1. Demographic Information

2.4.2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [25]

2.4.3. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [29]

2.4.4. Adapted Sexual Self-Efficacy Scale for Female Sexual Functioning (SSES-F) [30]

2.4.5. The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS) [31]

2.4.6. Brunnsviken Brief Quality of Life Scale (BBQ) [32]

2.4.7. State Self-Compassion (with Mindfulness) Short Form [33]

2.4.8. Feedback Questions

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Impact of Time on Mindful Compassion, Sexual Functioning, Sexual Self-Efficacy, Well-Being and Quality of Life

3.2. Comparisons Across Groups

3.3. Sexual Functioning with the Use of THC and CBD Suppositories

3.4. CO Group (n = 17 Participant Responses)

3.5. MC Group (n = 18 Participant Responses)

3.6. COMC Group (n = 18 of Participant Responses)

3.7. CAU Group (n = 16 of Participant Reponses)

4. Discussion

MC and COMC Groups

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Healthcare and Excellence. Cannabis-Based Medicinal Products NICE Guideline. 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng144 (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obora, M.; Onsongo, L.; Ogutu, J.O. Determinants of sexual function among survivors of gynaecological cancers in a tertiary hospital: A cross-sectional study. Ecancer Med. Sci. 2022, 16, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masaud, H.K.; Mohammed, R.A.; Ramadan, S.A.E.S.; Hassan, H.E. Impact of protocol of nursing intervention on sexual dysfunction among women with cervical cancer. J. Nurs. Sci. Benha. Univ. 2021, 2, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Wang, L.; Xing, J.; Shan, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, X. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women with cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brotto, L.A.; Erskine, Y.; Carey, M.; Ehlen, T.; Finlayson, S.; Heywood, M.; Kwon, J.; McAlpine, J.; Stuart, G.; Thomson, S.; et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brotto, L.A.; Yule, M.; Breckon, E. Psychological interventions for the sexual sequelae of cancer: A review of the literature. J. Cancer Surviv. 2010, 4, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, G.C.; Labate, R.C. Psychological repercussions related to brachytherapy treatment in women with gynecological cancer: Analysis of production from 1987 to 2007. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2008, 16, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banbury, S.; Chandler, C.; Lusher, J.A. Systematic Review Exploring the Effectiveness of Mindfulness for Sexual Functioning in Women with Cancer. Psych 2023, 5, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.L.; Wender, D.B.; Sloan, J.A.; Dalton, R.J.; Balcueva, E.P.; Atherton, P.J.; Bernath, A.M.; DeKrey, W.L.; Larson, T.; Bearden, J.D.; et al. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate transdermal testosterone in female cancer survivors with decreased libido; North Central cancer treatment group protocol N02C3. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guidozzi, F. Estrogen therapy in gynecological cancer survivors. Climacteric 2013, 16, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frühauf, S.; Gerger, H.; Schmidt, H.M.; Munder, T.; Barth, J. Efficacy of psychological interventions for sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Sex Behav. 2013, 42, 915–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banbury, S.; Lusher, J.; Snuggs, S.; Chandler, C. Mindfulness-based therapies for men and women with sexual dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2021, 38, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotto, L.A.; Bergeron, S.; Zdaniuk, B.; Driscoll, M.; Grabovac, A.; Sadownik, L.A.; Smith, K.B.; Basson, R. Comparison of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Treatment of Provoked Vestibulodynia in a Hospital Clinic Setting. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banbury, S.; Chander, C.; Lusher, J.; Karyofyllis, Z. A pilot RCT of an online mindfulness-based cognitive intervention for chemsex. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2023, 24, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Germer, C.K. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, F.; Vosper, J.; Gibson, S.; Jamieson, R.; Zelin, J.; Barter, J. Compassion Focused Psychosexual Therapy for Women Who Experience Pain during Sex. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2022, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Prasad, N.; Roy, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Biswas, A.S.; Patil, J.; Rath, G.K. Sexual dysfunction in females after cancer treatment: An unresolved issue. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, A.L.; Gingher, E.L.; Coleman, J.S. Medical Cannabis for Gynecologic Pain Conditions: A Systematic Review. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulating Medicines and Medical Devices (MHRA). The Supply, Manufacture, Importation and Distribution of Unlicensed Cannabis-Based Products for Medicinal Use in Humans ‘Specials’. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e58eefb86650c53a363f77c/Cannabis_Guidance__unlicensed_CBPMs__updated_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Mücke, M.; Phillips, T.; Radbruch, L.; Petzke, F.; Häuser, W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD012182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maayah, Z.H.; Takahara, S.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Dyck, J.R. The molecular mechanisms that underpin the biological benefits of full-spectrum cannabis extract in the treatment of neuropathic pain and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, S.; Chandler, C.; Erridge, S.; Olvera, J.d.R.; Turner, J.; Lusher, J. A Preliminary Study Looking at the Use of Mindful Compassion and Cannabis Suppositories for Anodyspareunia among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM). Psychoactives 2024, 3, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-7167-2850-4/0-7167-2850-8. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, S.; Jean-Marie, D.; Lusher, J.; Chandler, C.; Turner, J. The impact of a brief online mindfulness intervention to support erectile dysfunction in African Caribbean men: A pilot waitlist controlled randomised controller trial and content analysis. Rev. Psicoter 2024, 35, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Brown, C.; Heiman, J.B.; Leiblum, S.; Meston, C.; Shabsigh, R.; Ferguson, D.; D’Agostino, R., Jr. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailes, S.; Fichten, C.; Libman, E.; Brender, W.; Amsel, R. Sexual Self-Efficacy Scale for Female Functioning. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures; Fisher, T., Davis, C., Yarber, W., Davis, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lindner, P.; Frykheden, O.; Forsström, D.; Andersson, E.; Ljótsson, B.; Hedman, E.; Andersson, G.; Carlbring, P. The Brunnsviken Brief Quality of Life Scale (BBQ): Development and Psychometric Evaluation. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Psychological Society (BPS., Internet Mediated). Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research. 2017. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/ethics-guidelines-internet-mediated-research (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Brotto, L.A.; Stephenson, K.R.; Zippan, N. Feasibility of an Online Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Women with Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pernilla, M.; Lance, M.; Johanna, E.; Thomas, P.; JoAnne, D. Women, Painful Sex, and Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, H.; Madankan, F.; Azin, S.A.; Nasiri, M.; Montazeri, A. Sexual quality of life and sexual self-efficacy among women during reproductive-menopausal transition stages and post menopause: A comparative study. Women’s Midlife Health 2021, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaeian, S.; Navidian, A.; Rahiminezhad, M. Effect of mindfulness on sexual self-efficacy and sexual satisfaction among Iranian postmenopausal women: A quasi-experimental study. Sex Med. 2023, 11, qfad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Small, E. Cannabis: A Complete Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El Salam, A.; Ali, R.; Hassan, H. Outcome of an educational program on body image distress associated with cervical cancer. J. Adv. Trends Basic Appl. Sci. 2021, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, S.E.A. Cannabis Under the Influence of Yoga: The Impact of Mindful Movement on Well-Being Outcomes After Cannabis Use (T). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of British Columbia, British, Columba, 2023. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0435753 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Macey, K.; Gregory, A.; Nunns, D.; das Nair, R. Women’s experiences of using vaginal trainers (dilators) to treat vaginal penetration difficulties diagnosed as vaginismus: A qualitative interview study. BMC Womens Health 2015, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deaton, A.; Cartwright, N. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 210, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- NHS Gloucestershire. Vaginal Dilators and Sexual Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.gloshospitals.nhs.uk/your-visit/patient-information-leaflets/vaginal-dilators-and-sexual-care-ghpi1685_10_21/#:~:text=Apart%20from%20using%20dilators%2C%20vaginal,will%20help%20make%20this%20easier (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Brenner, P.S.; DeLamater, J. Lies, Damned Lies, and Survey Self-Reports? Identity as a Cause of Measurement Bias. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2016, 79, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Handy, A.; Meston, C. 028 A Novel Technique for Assessing Vaginal Lubrication. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15 (Suppl. 2), S108–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, B.C.; Rehal, S.; Cro, S. Risk of selection bias in randomised trials. Trials 2015, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| N = 83 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | % | ||

| CO | 21 | ||

| MC | 21 | ||

| COMC | 21 | ||

| CAU | 20 | ||

| Age | |||

| 18–30 | 11 | 13.3 | |

| 31–50 | 51 | 61.4 | |

| >51 | 21 | 25.3 | |

| Menopause, including early menopause | 43 | 51.8 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 52 | 62.7 | |

| African Caribbean | 30 | 36.1 | |

| Pakistani | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Sexuality | |||

| Straight | 77 | 92.8 | |

| Bisexual | 6 | 7.2 | |

| Relationship status (years) | |||

| 0–1 | 7 | 8.4 | |

| 1–2 | 15 | 18.1 | |

| 3–5 | 11 | 13.3 | |

| >5 | 29 | 34.9 | |

| Not partnered | 21 | 25.4 | |

| Outsider cannabis suppository use, Illicit drug use included | |||

| None | 53 | 63.9 | |

| Cocaine | 7 | 8.4 | |

| Amphetamine/speed | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Outside of post-cancer treatments | |||

| No medication | 44 | 53 | |

| Herat medication | 26 | 31.3 | |

| Insulin | 13 | 15.7 | |

| Alcohol Use | |||

| None | 23 | 27.7 | |

| <14 units | 49 | 59 | |

| >14 units | 11 | 13.3 | |

| Exercise | |||

| None | 42 | 50.6 | |

| Approximately 3 times per week | 15 | 18.1 | |

| Weekly | 18 | 21.7 | |

| Not stated | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Stage of cancer at the time of cancer treatment | |||

| Stage 1 | 41 | 49.4 | |

| Stage 2 | 39 | 47 | |

| Stage 3 | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Type of gynaecological cancer | |||

| Uterine | 43 | 51.8 | |

| Cervical | 30 | 36.1 | |

| Vaginal | 7 | 8.4 | |

| Vulva | 3 | 3.6 | |

| Cancer treatment | |||

| Surgery | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Radiotherapy | 9 | 10.8 | |

| Chemotherapy | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Combined radiotherapy, chemotherapy and hormones | 38 | 45.8 | |

| Hormones | 14 | 16.9 | |

| Targeted therapy | 6 | 7.2 | |

| Use of Cannabis suppositories | |||

| THC | 12 | 14.5 | |

| CBD | 11 | 13.3 | |

| THC/CBD combined | 19 | 22.9 | |

| Not applicable | 41 | 49.4 | |

| Estimated dose of cannabis suppository (mg) | |||

| 100 | 11 | 13.3 | |

| 500 | 10 | 12 | |

| 1000 | 16 | 19.3 | |

| Unsure | 5 | 6 | |

| Not applicable | 41 | 49.4 | |

| Frequency of use of cannabis suppositories | |||

| Every 2 weeks | 22 | 26.5 | |

| Weekly | 13 | 15.7 | |

| More than weekly | 12 | 14.5 | |

| Not applicable | 41 | 49.4 | |

| CO | MC | COMC | CAU | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Sexual function | ||||||||

| 0 | 20.29 | 3.196 | 22.90 | 4.134 | 22.91 | 4.136 | 17.60 | 3.050 |

| 4 | 21.48 | 3.219 | 23.24 | 3.048 | 23.76 | 2.965 | 17.56 | 2.895 |

| 12 | 21.88 ** | 3.407 | 24.440 * | 2.064 | 27.17 ** | 3.258 | 16.54 | 2.670 |

| Sexual desire | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.19 | 1.030 | 2.38 | 0.921 | 2.33 | 0.856 | 1.90 | 0.788 |

| 4 | 2.38 | 0.921 | 2.43 | 0.870 | 2.38 | 0.921 | 1.89 | 0.758 |

| 12 | 2.35 | 0.786 | 2.56 | 0.616 | 2.57 | 0.659 | 1.87 | 0.719 |

| Sexual arousal | ||||||||

| 0 | 4.71 | 1.554 | 3.90 | 1.136 | 3.91 | 1.156 | 4.25 | 1.164 |

| 4 | 4.67 | 1.550 | 4.19 | 0.928 | 4.24 | 0.831 | 4.33 | 1.138 |

| 12 | 4.71 | 1.047 | 4.61 * | 0.788 | 4.38 * | 0.786 | 4.38 | 0.957 |

| Lubrication | ||||||||

| 0 | 3.67 | 1.390 | 4.00 | 1.095 | 4.19 | 1.03 | 2.80 | 1.322 |

| 4 | 3.90 | 1.179 | 4.49 | 1.096 | 4.19 | 1.03 | 2.94 | 1.259 |

| 12 | 3.88 | 1.166 | 4.56 * | 1.097 | 5.00 * | 1.029 | 2.81 | 1.276 |

| Orgasms | ||||||||

| 0 | 2.05 | 1.244 | 2.05 | 1.244 | 2.05 | 1.244 | 2.80 | 1.322 |

| 4 | 3.10 | 1.091 | 2.19 | 1.25 | 2.38 | 1.284 | 2.94 | 1.256 |

| 12 | 3.88 | 1.166 | 2.50 * | 1.295 | 2.94 * | 1.662 | 2.81 | 1.276 |

| Sexual satisfaction | ||||||||

| 0 | 3.10 | 1.221 | 4.00 | 1.871 | 4.11 | 1.623 | 2.80 | 1.105 |

| 4 | 3.67 | 1.713 | 4.05 | 1.746 | 4.10 | 1.609 | 2.67 | 1.085 |

| 12 | 3.94 | 1.952 | 4.06 | 0.988 | 5.00 | 1.188 | 2.69 | 1.138 |

| Sexual pain | ||||||||

| 0 | 6.57 | 1.832 | 6.57 | 1.832 | 6.83 | 1.543 | 6.2 | 2.042 |

| 4 | 4.00 | 1.225 | 6.38 | 1.396 | 6.57 | 1.832 | 6.22 | 1.734 |

| 12 | 3.76 ** | 1.261 | 6.17 | 1.2 | 4.06 * | 1.955 | 6.19 | 1.759 |

| Mindful compassion | ||||||||

| 0 | 23.24 | 5.873 | 23.71 | 6.597 | 24.01 | 5.161 | 17.50 | 3.935 |

| 4 | 22.76 | 5.309 | 34.10 | 3.145 | 36.48 | 3.669 | 17.17 | 3.746 |

| 12 | 22.06 | 5.771 | 36.78 ** | 3.859 | 37.56 ** | 3.944 | 17.00 | 3.596 |

| Well-being | ||||||||

| 0 | 18.86 | 4.078 | 13.33 | 3.152 | 13.39 | 3.162 | 21.80 | 3.563 |

| 4 | 22.81 | 3.487 | 16.86 | 3.439 | 19.67 | 3.411 | 19.50 | 3.015 |

| 12 | 19.41 ** | 3.709 | 22.00 ** | 3.581 | 23.78 ** | 3.001 | 17.50 ** | 3.141 |

| Sexual self-efficacy | ||||||||

| 0 | 15.19 | 2.502 | 15.38 | 2.156 | 15.38 | 2.156 | 18.00 | 3.325 |

| 4 | 15.86 | 2.762 | 22.33 | 3.246 | 23.62 | 3.413 | 17.39 | 2.831 |

| 12 | 17.65 * | 3.673 | 25.39 ** | 3.032 | 26.72 * | 4.012 | 15.06 * | 2.048 |

| Quality of life | ||||||||

| 0 | 18.81 | 4.697 | 17.10 | 3.048 | 17.60 | 4.144 | 21.60 | 5.423 |

| 4 | 19.10 | 4.504 | 18.86 | 2.651 | 19.62 | 2.889 | 21.56 | 4.949 |

| 12 | 20.24 | 1.505 | 19.17 * | 2.975 | 19.18 * | 2.959 | 21.31 | 4.827 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banbury, S.; Tharmalingam, H.; Lusher, J.; Erridge, S.; Chandler, C. A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of Cannabis Suppositories and Online Mindful Compassion for Improving Sexual Function Among Women Following Gynaecological Cancer Treatment. Medicina 2024, 60, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60122020

Banbury S, Tharmalingam H, Lusher J, Erridge S, Chandler C. A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of Cannabis Suppositories and Online Mindful Compassion for Improving Sexual Function Among Women Following Gynaecological Cancer Treatment. Medicina. 2024; 60(12):2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60122020

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanbury, Samantha, Hannah Tharmalingam, Joanne Lusher, Simon Erridge, and Chris Chandler. 2024. "A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of Cannabis Suppositories and Online Mindful Compassion for Improving Sexual Function Among Women Following Gynaecological Cancer Treatment" Medicina 60, no. 12: 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60122020

APA StyleBanbury, S., Tharmalingam, H., Lusher, J., Erridge, S., & Chandler, C. (2024). A Preliminary Investigation into the Use of Cannabis Suppositories and Online Mindful Compassion for Improving Sexual Function Among Women Following Gynaecological Cancer Treatment. Medicina, 60(12), 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60122020