Abstract

Background and Objectives: In Saudi Arabia, persons with disabilities (PWDs) face considerable oral health challenges, including a higher prevalence of dental caries and gingival inflammation, which adversely affects their oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). This population experiences distinct and substantial barriers in accessing adequate dental care. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to quantify disparities in OHRQoL between PWDs and individuals without disabilities in Saudi Arabia, focusing on caries and gingivitis prevalence, and to identify specific areas for intervention. Materials and Methods: A structured search of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar yielded 803 articles, of which seven met the inclusion criteria. These studies reported on OHRQoL and oral health outcomes in populations with autism, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and hearing impairments. Data on caries rates, gingival health, and self- or caregiver-reported quality of life were extracted and analysed. Results: PWDs in Saudi Arabia exhibit significantly higher caries prevalence (ranging from 60% to over 80%) and moderate-to-severe gingival inflammation (up to 60%) compared to individuals without disabilities. The caregivers of children with disabilities reported heightened stress levels, and PWDs experienced reduced functional and social well-being. These disparities were compounded by limited preventive care access and high unmet treatment needs, particularly among those with severe disabilities and limited caregiver support. Conclusions: PWDs in Saudi Arabia face marked oral health disparities, with notably higher rates of dental caries and gingivitis, severely impacting their quality of life. The findings underscore the need for targeted oral health policies and community-based interventions to enhance care accessibility, promote preventive measures, and address the unique needs of this vulnerable population.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1.3 billion people, or about 16% of the global population, currently experience significant disability. This number is rising due to factors such as population ageing and an increase in chronic health conditions. Disability is an inherent part of the human experience, with most people likely to encounter temporary or permanent disability at some point in their lives. Persons with disabilities (PWDs) are at higher risk for conditions such as depression and poor oral health, and they face greater challenges in accessing healthcare [1]. The most common disabilities and disorders affecting oral health include intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, epilepsy, and sensory impairments [2,3,4,5,6,7].

The standard of living impacts health outcomes, especially for those with disabilities or genetic conditions. Wealthier nations provide better access to prenatal testing, allowing for early detection of genetic issues, which can lead to fewer births of individuals with significant genetic disabilities due to selective pregnancy terminations [8]. Limited access to prenatal care in lower-income nations often results in higher rates of disabilities from birth [9]. Additionally, developed nations generally promote greater health awareness and provide better access to healthcare services for people with disabilities, leading to improved quality-of-life and health outcomes, such as better oral health and preventive care [10,11,12].

The caregiving environment also plays a critical role in the quality of life of individuals with disabilities. Research shows that those living alone may experience a greater sense of autonomy but face risks of isolation. Family caregiving offers emotional support but may strain caregivers, affecting care quality [13]. Specialised care facilities provide structured care with professional support, yet quality varies by resources [13]. Personal assistance programmes can support independence but rely on funding availability, so are often limited to wealthier regions [14]. The type of caregiving also impacts health; for instance, institutional care offers preventive health access [15], while family or personal care may be more individualised but with fewer resources.

Oral health is crucial to overall health and significantly impacts patients’ lives, as represented by the concept of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) [16]. Traditionally, oral health has been defined as the absence of disease [17]. However, contemporary definitions recognise that oral health is multifaceted and extends beyond this definition [17]. The WHO characterises oral health as the condition of the mouth, teeth, and orofacial structures that enables individuals to carry out essential functions such as eating, breathing, and speaking. It also involves psychosocial elements such as self-esteem, overall well-being, and the ability to interact socially and work without pain, discomfort, or embarrassment [18].

Specific conditions associated with various disabilities directly affect oral health. For instance, individuals with Down syndrome are more prone to periodontal disease [19], and those with ASD may have heightened sensitivity that makes routine dental care challenging [20]. Individuals with cerebral palsy are at higher risk for occlusal problems, such as Class II malocclusion and anterior open bite [4]. Medications commonly prescribed for various disabilities can also have side effects that impact oral health, such as dry mouth, which increases the risk of dental caries and other pathologies [21]. However, PWDs often encounter barriers in accessing oral healthcare services [22], leading to poorer oral health outcomes and high unmet dental needs [23,24].

In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of PWDs is a significant public health concern. Approximately 1 in every 30 citizens has some form of disability [25]. Recent studies have highlighted disparities in oral health outcomes and healthcare utilisation [26,27] among PWDs in the country. These findings underscore the urgent need for tailored interventions and policies to effectively address the specific oral health needs of this vulnerable population.

While the global literature provides valuable insights into the oral health disparities faced by PWDs [1,10], there remains a critical need to systematically review and synthesise existing evidence specific to Saudi Arabia. Understanding the OHRQoL among PWDs in Saudi Arabia requires a thorough assessment that considers their unique oral healthcare challenges, cultural context, and access to dental services [26,27].

A patient’s perceived health status is influenced by a multitude of factors and is not merely a reflection of their physical health. Environmental factors such as physical surroundings and social contexts, including family, friends, and coworkers, as well as personal factors such as personality traits and lifestyle, significantly shape an individual’s health perceptions [28]. The primary goal of oral healthcare is to mitigate the effects of oral diseases, focusing on improving OHRQoL. Patient-centred dental interventions aim to reduce suffering and enhance OHRQoL, ensuring that outcomes are perceived as beneficial by the patient. OHRQoL is not only crucial for individual patients but also serves as a key indicator for dental public health [29].

This review aims to address this gap by critically analysing peer-reviewed studies that investigate the OHRQoL among PWDs within the Saudi Arabian context. By understanding the extent of oral health disparities, this review seeks to provide policymakers, healthcare providers, and stakeholders with valuable insights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration and Focused Question

A protocol was created and registered on PROSPERO prior to conducting the review (PROSPERO: CRD42024550699). Following the Participants, Exposure, Comparison, and Outcomes (PECO) framework outlined in the PRISMA guidelines [30], the following focused research question was developed: In Saudi Arabia, is the OHRQoL (Outcome) of PWDs (Participants with Exposure) similar to or lower than that of persons without any disability (Comparison)? The PECO elements used in this review are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

PECO elements used for this review.

The patient population included individuals in Saudi Arabia with various developmental and intellectual disabilities impacting oral health, such as cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, and hearing impairments. The review considered patients across a range of ages, from early childhood to adulthood, to capture a broad perspective on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among these groups. Specific inclusion criteria required that studies assess oral health using clinical indices such as the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), and various quality-of-life measures, including the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ) and Parent–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ).

2.2. Literature Search

2.2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

The search strategy involved a structured and comprehensive search across four databases: PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Using a combination of MeSH terms and Boolean operators, the search was tailored to include keywords related to oral health, specific disabilities, and Saudi Arabia. Specific terms included “dental health”, “oral hygiene”, and “oral health accessibility” and conditions such as “cerebral palsy”, “autism”, and “Down syndrome”. Google Scholar was included to capture grey literature and studies not indexed in the major databases. Search terms were structured using the MeSH terms and Boolean operators provided in Supplementary File S1. The initial search was performed by a medical information specialist. Screening was performed by two reviewers (FYA and EK). Any disagreements were solved by discussion. The search results were limited to 20 pages on Google Scholar to ensure manageability.

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Only primary studies published in peer-reviewed journals and written in English were considered eligible. Additionally, studies had to be published within the last 25 years to ensure relevance and timeliness of the findings. These criteria aimed to focus the review on recent research that directly addressed the intersection of oral health status and quality of life among PWDs in Saudi Arabia.

2.2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria ruled out studies not conducted in Saudi Arabia, non-peer-reviewed articles, interventional studies, articles not available in English, studies focusing solely on general health without specific reference to oral health, and review studies. Monthly updates of the search were repeated before the final revision of the manuscript.

2.2.4. Study Selection Process

The study selection process involved initial searches in all databases, followed by title and abstract screening to identify potentially relevant studies, full-text reviews of articles meeting the initial criteria, and data extraction. All searches and reviews were performed independently by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The initial search was conducted on 1 July 2024 and the last update was carried out on 25 September.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (FYA and EK) screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved records against predefined inclusion criteria. Data extraction forms were piloted and optimised before being finalised in Microsoft Excel. Studies eligible for full-text review underwent detailed assessment by the same reviewers to determine final inclusion based on relevance to the review objectives and criteria. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer (MT) when necessary. Data pertaining to the following categories were extracted: study name and year, study design, disabilities and relevant groups assessed, age and sex information, OHRQoL measures assessed, and reporting methods. Any outcomes related to OHRQoL were extracted for qualitative and quantitative syntheses. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

2.4. Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.4 software, applying a random effects model to account for potential variations across the included studies. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic, which quantifies the proportion of total variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The results of this analysis include p-values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to support statistical interpretations.

3. Risk of Bias

For the cross-sectional studies, JBI’s Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies was used to assess overall bias [31]. Briefly, it includes several key domains to evaluate the methodological rigour and reliability of such studies. These domains encompass (a) a clear definition of inclusion criteria for sample selection, ensuring transparency in participant recruitment; (b) a detailed description of study subjects and settings to facilitate comparability with the target population; (c) the validation and reliability of exposure measurement methods, ensuring accuracy and consistency; (d) the use of objective criteria for measuring conditions, minimising bias in diagnostic processes; (e) the identification and acknowledgment of confounding factors that could influence study outcomes; (f) explicit strategies to address and control for confounding effects, either through study design or statistical analysis; (g) the validation and reliability of outcome measurement tools, ensuring accurate assessment of study endpoints; and (h) the appropriate application of statistical analyses tailored to study objectives and data characteristics.

Since one case–control study was identified, the JBI tool for case–control studies was used to assess the risk of bias [32]. The tool assesses case and control selection, ensuring groups are representative and well-defined to avoid misclassification or selection bias. The tool also checks if cases and controls are matched on confounding variables (e.g., age, gender) or if statistical methods control for these differences, reducing unrelated variation. Consistency in exposure measurement across groups is reviewed to prevent measurement bias, and non-respondents are considered to avoid response bias. Lastly, it examines the statistical methods used to confirm appropriate analyses for accurate interpretation of exposure–outcome relationships.

The risk-of-bias assessment was performed by two independent reviewers (FYA and EK). Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer (MT) when necessary.

4. Results

4.1. Literature Search and Description of Included Studies

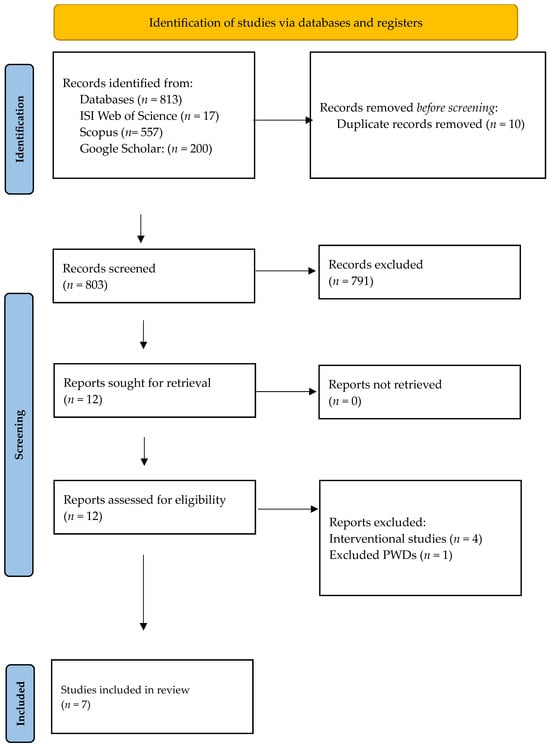

The initial search yielded 813 records. After excluding 10 duplicates, 803 articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Covidence was used for management of the bibliography and duplicates were removed using the automation feature. Cohen’s Kappa for literature screening was 0.91, for data extraction it was 0.79, and for risk of bias it was 0.72. Of these, 791 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. As a result, 12 articles were selected for full-text review. However, five of these articles were further excluded—four due to being interventional studies [33,34,35,36] and one because it did not specifically mention or include PWDs as part of its study population [37]. Ultimately, seven articles were included in this review [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. The results of the literature search are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection process.

4.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Six of the studies included in this review primarily employed cross-sectional designs [38,39,40,41,42,43].

Two studies focused on ASD [38,39]. The studies included in this review primarily used cross-sectional designs to explore oral health and quality-of-life outcomes among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) compared to neurotypical children. Pani’s study, a comparative cross-sectional study in Riyadh, involved 59 children with ASD (40 males and 17 females) and their 59 neurotypical siblings, aged 8 to 13 years. Using the parental perception questionnaire (P-CPQ) and the Family Impact Scale (FIS), this study gathered data reported by parents to assess perceived oral health quality of life [38]. Similarly, Alaki conducted a comparative cross-sectional study across ten autism centres in Jeddah, assessing 75 children with ASD (17 females, 22.7%) and 99 children without ASD (40 females, 40.4%), aged 6 to 12 years. The study utilised the Franciscan Hospital for Children Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (FHC-OHRQOL) questionnaire, also with data reported by parents, to evaluate perceived oral health impacts [39]. Both studies revealed trends in caregiver-reported oral health outcomes, emphasising challenges in maintaining oral health for children with ASD. While Pani’s study focused on the overall impact on the family using the FIS, Alaki’s study was specifically centred on the child’s quality of life as measured using FHC-OHRQOL, highlighting variations in the emphasis of quality-of-life assessments. Additionally, clinical oral health indices, such as plaque scores and decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) scores, were evaluated to provide an objective measure of oral health status in these populations.

The other studies referenced share a common focus on assessing oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in children and adults with various disabilities, though they differ in terms of population characteristics, conditions, and assessment tools. Alkahtani et al.’s cross-sectional study in Riyadh assessed 146 adults (18 years and above) with hearing impairment, including 105 females and 41 males, using the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), a self-reported questionnaire that evaluates perceived oral health quality of life [40]. Pani et al., also in Riyadh, conducted a cross-sectional study with 45 children (ages 13–17) with cerebral palsy, including 25 females and 21 males, using child and parental perception scores to assess OHRQoL [41]. Similarly, AlJameel et al. performed a cross-sectional study with 63 children (ages 10–14) with Down syndrome, including 36 females (57%) and 27 males (43%), focusing on self-reported data from the children to measure their OHRQoL [42]. AlWattban’s study in Qassim involved 107 children (ages 4–12) with multiple disabilities, using the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (A-ECOHIS) with caregiver-reported data to assess the impact of oral health on the children’s lives [43]. Finally, AlShehri et al. conducted a case–control study in Abha with 180 children, 150 with disabilities and 30 without, using the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version, with data reported by both parents and children [44]. The general characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

General characteristics of included studies assessing OHRQoL among PWDs.

4.3. Qualitative Outcomes

4.3.1. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL)

Pani et al. found that siblings of autistic children scored lower in the functional limitations, emotional well-being, and social well-being domains compared to autistic children and those from non-autistic families, although no differences were observed in the oral symptoms domain. Families with autistic children had higher scores in parental emotion and family finances domains, indicating an increased emotional and financial burden [38].

Alaki et al. reported that children with autism experienced greater daily life challenges, parental concerns (p = 0.004 and p = 0.008), and poorer oral well-being (p = 0.000 to p = 0.001) than controls. Their study also highlighted that these children had higher caries prevalence (p = 0.013) and severity (p = 0.003) [39].

AlJameel et al. noted a significant impact of oral health on quality of life for both children with Down syndrome and their families. Specifically, 34.9% of children and 46% of families reported substantial impacts on quality of life, with children experiencing physical pain (54%) and families experiencing negative emotional impacts [42].

AlWattban et al. found that early childhood oral health issues significantly affected OHRQoL, especially for children with severe caries. However, the negative impact was less pronounced among children with educated caregivers or caregivers in the health sector. The average A-ECOHIS score was 10.93, and 95.3% of children were affected [43].

Alshehri et al. observed that parents of disabled children experienced significantly higher stress levels (p = 0.004). Factors such as dental caries severity, plaque accumulation, and caregiver education were found to significantly impact children’s OHRQoL, while BMI was not significantly related to oral health indicators [44].

4.3.2. Clinical Oral Health Indices

Alkahtani et al. reported that over half of the children examined had fair oral hygiene (55.2%) and moderate gingival inflammation (60.1%). Significant differences in oral health scores were found between Saudi and non-Saudi children (1.64 vs. 1.12, p = 0.041), along with a high prevalence of dental caries (82.2%) and treatment needs (85.6%) [40].

Pani et al. identified that children with greater gross motor function impairments had significantly higher scores in both the child and parental perception questionnaires. Additionally, these children exhibited higher decayed, missing, and filled teeth counts (p = 0.002) and higher gingival index scores (p = 0.001) [41].

The overall outcomes of the studies are included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Oral health-related quality of life variables and outcomes in the reviewed studies.

4.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment Results

The quality assessment of the cross-sectional studies revealed that most adhered to the key methodological criteria. The majority of studies met the requirements for inclusion, subject selection, setting, and exposure measurement. However, there were some differences in how confounding factors were addressed. For instance, Pani [38], Alkahtani [40], and AlJameel [42] did not consider confounding factors in their analyses (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality assessment of included studies using JBI checklist for cross-sectional studies.

While the case–control study by Al-Shehri et al. (2014) [44] reported the associations between plaque and dental caries and evaluated parental stress in both groups, it also relied on caregiver-reported data, which may introduce reporting bias to the overall results (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk-of-bias assessment results for Al-Shehri et al. (2014) [44], using JBI checklist for case–control studies.

4.5. Results of the Meta-Analysis

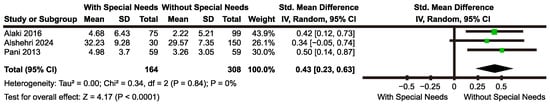

The meta-analysis comparison of parental indices indicated there was a significantly higher concern among parents of children with disabilities. Two of the included studies focused on autism spectrum disorder (ASD), while one study did not specify the type of disabilities among the participants [23,24,29]. The forest plot reveals a combined standard mean difference (SMD) of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.23 to 0.63), indicating that parents of PWDs have a higher magnitude of stress or concerns compared to those without disabilities. The heterogeneity analysis shows an I2 of 0%, suggesting no observed variability between the study results. The overall effect test result is highly significant (z = 4.17; p < 0.0001), underscoring a consistent and statistically significant difference favouring the group with disabilities. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of these results.

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing parental concern indices between parents of children with and without special needs [23,24,29].

5. Discussion

This systematic review examined oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Saudi Arabia, revealing substantial disparities in their oral health outcomes compared to their non-disabled peers. The findings indicate that PWDs—including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and hearing impairments—experience poorer oral health outcomes, such as a higher prevalence of dental caries, gingival inflammation, and lower overall OHRQoL [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. These results align with broader findings from Ningrum et al., who conducted a systematic review of 20 studies and reported significant oral health inequities among Asian children with disabilities compared to their healthy peers, emphasising a regional pattern of disparities in this population [45]. Similar studies in Saudi Arabia also underscore the diminished quality of life reported by caregivers of children with disabilities, likely exacerbating these disparities by reducing caregivers’ ability to provide consistent oral care [46].

These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to improve oral health outcomes for PWDs in Saudi Arabia. Interventional studies suggest that providing specialised dental treatments to PWDs can lead to significant improvements in OHRQoL, demonstrating the potential impact of accessible and tailored care options [33,34,35,36]. This review intends to further explore this topic in a subsequent systematic review, highlighting the importance of understanding intervention effectiveness across diverse groups.

The high rates of dental caries, gingival inflammation, and suboptimal oral hygiene observed in this population suggest that PWDs face considerable barriers to accessing and utilising oral healthcare services. For instance, elevated parental stress and lower OHRQoL scores among children with disabilities point to the broad impact that poor oral health has on both individuals and their families [38,39]. The higher parental concerns reported in these studies may also indicate increased awareness and willingness among caregivers to seek oral health interventions for their children with disabilities. However, these findings collectively suggest that current healthcare services may not be sufficiently meeting the needs of PWDs, necessitating the implementation of comprehensive strategies to improve the accessibility and quality of care.

The clinical implications of these disparities are significant. Poor oral health can adversely impact overall health and well-being, affecting essential functions such as nutrition, communication, and social interaction. For PWDs, untreated health issues can exacerbate pre-existing conditions, thereby further diminishing their quality of life and social integration [45,46]. These disparities call for action from policymakers, healthcare providers, and stakeholders to implement and support evidence-based interventions that address the unique needs of PWDs and bridge gaps in care access and quality. Targeted efforts to improve oral health outcomes for PWDs in Saudi Arabia could ultimately help reduce these disparities and enhance overall well-being for this vulnerable population.

While this review is among the few studies to evaluate the influence of OHRQoL on PWDs, providing valuable insights into oral health disparities through a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis in Saudi Arabia, several limitations warrant consideration. First, most of the studies included were cross-sectional, capturing data only at a single point in time and limiting insights regarding causality. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs to better elucidate causal relationships between disability status and oral health outcomes. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported or caregiver-reported data may introduce recall bias, potentially affecting data accuracy. This limitation suggests a need for objective clinical assessments in future studies to enhance the reliability of findings. Evidence highlights the ongoing exclusion of children with disabilities from oral health research, which limits the development of strategies tailored to their unique needs and perpetuates oral health disparities [47]. Future research should prioritise inclusive methodologies that actively involve children with disabilities. By adopting such approaches, researchers can better inform the design of targeted services and policies, ultimately reducing inequalities in oral health outcomes. Additionally, this review was limited to studies published in English, which may have resulted in an incomplete picture due to excluding potentially relevant studies in other languages.

Cultural and systemic factors, such as stigma surrounding disabilities, reliance on family caregivers, and limited awareness of their specific needs, may influence access to healthcare services, potentially impacting oral health quality of life. Further research should investigate the specific impact of these factors on oral health-related quality of life to better inform targeted interventions and policies [48]. While these challenges are not unique to Saudi Arabia, they manifest differently across sociocultural and healthcare contexts [49], highlighting the importance of contextualising findings regionally while considering global relevance. The included studies varied in design, assessment tools, and sample populations, adding variability to the findings. While meta-analyses allow for some generalisation of the results, caution is suggested in applying these results universally due to the variability in assessment tools and populations. Standardised assessment methods are crucial for improving comparability across studies, thereby facilitating more robust conclusions.

In addressing these oral health disparities, it is essential to develop, test, and implement tailored interventions for PWDs. Effective interventions should prioritise accessibility, affordability, and quality of care, ensuring that PWDs receive equitable oral health services. Collaborative efforts among policymakers, healthcare providers, and community organisations are critical for creating and sustaining such initiatives. By fostering partnerships across these sectors, stakeholders can work together to promote improved oral health outcomes for PWDs, ultimately reducing health disparities and enhancing quality of life for this underserved population.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review reveals substantial disparities in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Saudi Arabia. PWDs experience poorer oral health outcomes—including higher rates of dental caries, gingival inflammation, and reduced OHRQoL—compared to their non-disabled peers. These findings underscore an urgent need for targeted, accessible interventions to address these inequities and improve oral healthcare access for this vulnerable population. Addressing these disparities is essential to promoting the overall health, well-being, and quality of life of PWDs, highlighting the role of tailored healthcare strategies and collaborative support from policymakers, healthcare providers, and communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina60122005/s1: Supplementary File S1: Search terms used in the included databases.

Author Contributions

F.Y.I.A. and E.K. conducted the review, screened the studies, and extracted the data from the included studies; M.T. was the third reviewer—responsible for resolving any conflicts and reviewing the manuscript; F.Y.I.A. wrote the manuscript with input and supervision from E.K. and M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no. KSRG-2023-025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors confirm that this review was carried out in accordance with the guidelines and standards established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Due to the nature of this review, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Study data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Western Australia for their support. The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2023-025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| A-ECOHIS | Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CPQ | Child perception questionnaire for adolescents |

| EWB | Emotional well-being |

| dmft | Decayed, missing, and filled teeth (primary dentition) |

| DMFT | Decayed, missing, and filled teeth (permanent dentition) |

| GMFCS | Gross Motor Function Classification Scores |

| FIS | Family Impact Scale |

| FL | Functional limitations |

| GI | Gingival index |

| GOHAI | General Oral Health Assessment Index |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| OHRQOL | Oral health-related quality of life |

| OHI | Oral health index-simplified |

| OS | Oral symptoms |

| PECO | Participants, Exposure, Comparison, and Outcomes |

| PICO | Participants, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes |

| PPQ | Parental perception questionnaire |

| P-CPQ | Parental–Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| PSI-SF | Parenting Stress Index-Short Form |

| SWB | Social well-being |

| PWD | Persons with disabilities |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version |

References

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Anders, P.L.; Davis, E.L. Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Spec. Care Dent. 2010, 30, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Como, D.H.; Stein Duker, L.I.; Polido, J.C.; Cermak, S.A. Oral health and autism spectrum disorders: A unique collaboration between dentistry and occupational therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensi, C.; Costacurta, M.; Docimo, R. Oral health in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spec. Care Dent. 2020, 40, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrefadi, R.; Beaayou, H.; Herwis, K.; Musrati, A. Oral health status in individuals with Down syndrome. Libyan J. Med. 2022, 17, 2116794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, M.; Johar, S.; Khokhar, A. Oral health considerations and dental management for epileptic children in pediatric dental care. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2023, 16, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé-Villar, B.; Mourelle-Martínez, M.R.; Diéguez-Pérez, M.; de Nova-García, M.J. Incidence of oral health in paediatric patients with disabilities: Sensory disorders and autism spectrum disorder. Systematic review II. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, e344–e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayefsky, M.J.; Berkman, B.E. Implementing Expanded Prenatal Genetic Testing: Should Parents Have Access to Any and All Fetal Genetic Information? Am. J. Bioeth. 2022, 22, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Ending Preventable Newborn Deaths and Stillbirths by 2030: Moving Faster Towards High-Quality Universal Health Coverage in 2020–2025; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/ending-preventable-newborn-deaths-stillbirths-quality-health-coverage-2020-2025 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- WHO. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Luan, Y.; Sardana, D.; Jivraj, A.; Liu, D.; Abeyweera, N.; Zhao, Y.; Cellini, J.; Bass, M.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; et al. Universal Coverage for Oral Health Care in 27 Low-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Global Health Res. Policy 2024, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y.M. Healthcare Facilities in Developing Countries: Infrastructure. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries; Al-Worafi, Y.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Doody, O.; Hennessy, T.; Moloney, M.; Lyons, R.; Bright, A.M. The Value and Contribution of Intellectual Disability Nurses/Nurses Caring for People with Intellectual Disability in Intellectual Disability Settings: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1993–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nally, D.; Moore, S.S.; Gowran, R.J. How Governments Manage Personal Assistance Schemes in Response to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Soc. 2021, 37, 1728–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bershadsky, J.; Taub, S.; Engler, J.; Moseley, C.R.; Lakin, K.C.; Stancliffe, R.J.; Larson, S.; Ticha, R.; Bailey, C.; Bradley, V. Place of Residence and Preventive Health Care for Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Services Recipients in 20 States. Public Health Rep. 2012, 127, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütte, U.; Heydecke, G. Oral health-related quality of life. In Encyclopedia of Public Health; Kirch, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, M.; Williams, D.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Vujicic, M.; Watt, R.G.; Weyant, R.J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/oral-health/#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rondón-Avalo, S.; Rodríguez-Medina, C.; Botero, J.E. Association of Down syndrome with periodontal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spec. Care Dent. 2024, 44, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Council on Clinical Affairs. Guideline on management of dental patients with special health care needs. Pediatr. Dent. 2012, 30, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, B.G.; Azoubel, M.C.F.; de Lima Dantas, J.B.; Medrado, A.R.A.P. Interrelation study between drugs and oral lesion development in patients with special needs. J. Oral. Diag. 2019, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadauria, U.S.; Purohit, B.; Priya, H. Access to dental care in individuals with disability: A systematic review. Evid. Based Dent. 2024, 25, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.; Clarke, L.; Stevens, C. Dental health for children with special educational needs and disability. Paediatr. Int. Child. Health 2022, 32, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambler, S.; Curtis, S.A. Contextualising disability and dentistry: Challenging perceptions and removing barriers. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindawas, S.M.; Vennu, V. The national and regional prevalence rates of disability, type, of disability and severity in Saudi Arabia—Analysis of 2016 demographic survey data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, F.Y.I.; Tennant, M.; Kruger, E. Oral health status, oral health behaviors, and oral health care utilization among persons with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, F.Y.I.; Tennant, M.; Kruger, E. Oral health of individuals with cerebral palsy in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2024, 52, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2001. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42407 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- John, M.T. Foundations of oral health-related quality of life. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2021, 48, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk (2020). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Meligy, O.; Maashi, M.; Al-Mushayt, A.; Al-Nowaiser, A.; Al-Mubark, S. The effect of full-mouth rehabilitation on oral health-related quality of life for children with special health care needs. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 40, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nowaiser, A.M.; Al Suwyed, A.S.; Al Zoman, K.H.; Robert, A.A.; Al Brahim, T.; Ciancio, S.G.; Al Mubarak, S.A.; El Meligy, O.A. Influence of full mouth rehabilitation on oral health-related quality of life among disabled children. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2017, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, N.M.; Farsi, D.J.; Farsi, N.J.; El-Housseiny, A.A.; Turkistan, J.M. Impact of dental rehabilitation on oral health-related quality of life in healthy children and those with special health care needs. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2018, 19, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeldin, T.; Bader, R.; Abougareeb, H.; Siddiqui, I.A.; Musa, B.A.; Alrashedi, S.; Alaswad, N.; Hakamy, A. Oral health-related quality of life improvement in children with special needs following comprehensive dental treatment under GA: A Saudi-based follow-up study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2023, 17, ZC24–ZC27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri, M.F.A.; Alwadani, M.A.; Talbi, K.M.; Hazzazi, R.A.A.; Eshaq, R.H.A.; Alabdali, F.H.J.; Wadani, M.H.M.; Tartaglia, G.; Ahmad, B. Exploring associations between oral health measures and oral health-impacted daily performances in 12–14-year-old schoolchildren. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, S.C.; Mubaraki, S.A.; Ahmed, Y.T.; AlTurki, R.Y.; Almahfouz, S.F. Parental perceptions of the oral health-related quality of life of autistic children in Saudi Arabia. Spec. Care Dentist. 2013, 33, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaki, S.M.; Khan, J.A.; El Ashiry, E.A. Parental perception of oral health-related quality of life in children with autism. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016, 10, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Alkahtani, F.H.; Baseer, M.A.; Ingle, N.A.; Assery, M.K.; Al Sanea, J.A.; AlSaffan, A.D.; Al-Shammery, A. Oral health status, treatment needs and oral health-related quality of life among hearing impaired adults in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 744. [Google Scholar]

- Pani, S.C.; AlEidan, S.F.; AlMutairi, R.N.; AlAbsi, A.A.; AlMuhaidib, D.N.; AlSulaiman, H.F.; AlFraih, N.W. The impact of gross motor function on the oral health-related quality of life in young adults with cerebral palsy in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 4590509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJameel, A.H.; AlKawari, H. Oral health-related quality of life of children with Down syndrome and their families: A cross-sectional study. Children 2021, 8, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwattban, R.R.; Alkhudhayr, L.S.; Ali, S.N.A.-H.; Farah, R.I. Oral health-related quality-of-life according to dental caries severity, body mass index and sociodemographic indicators in children with special health care needs. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, S.A.; Alshehri, S.A.; Alkahtani, Z.M.; Alkahtani, Z.M.; AlQhtani, F.A.; AlQhtani, F.A.; Rasayn, S.A.A.L.; Rasayn, S.A.A.L.; Alasere, R.N.; Alasere, R.N.; et al. Body mass index, oral health status and oral health-related quality of life among special health care needs children and parenting stress: A case-control study in southern Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 48, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningrum, V.; Bakar, A.; Shieh, T.-M.; Shih, Y.-H. The oral health inequities between special needs children and normal children in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare 2021, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiri, F.; Tedla, J.S.; Sangadala, D.R.; Reddy, R.S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Gular, K.; Dixit, S.; Kakaraparthi, V.N.; Nayak, A.; Aldarami, M.A.M.; et al. Quality of life among caregivers of children with disabilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. J. Disabil. Res. 2023, 2, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadi, M.A.M.; Baker, S.R.; Owens, J. Oral Health Experiences and Perceptions of Children with Disabilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadi, S.A. Why Does Saudi Arabia Have Fewer Leaders with Disabilities?: Changing Perspectives and Creating New Opportunities for the Physically Challenged in Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asiri, F.Y.I.; Tennant, M.; Kruger, E. Barriers to Oral Health Care for Persons with Disabilities: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Community Dent. Health 2024, 41, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).