A Comparative Analysis of Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Care in Intoxicated Patients with Acute Kidney Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

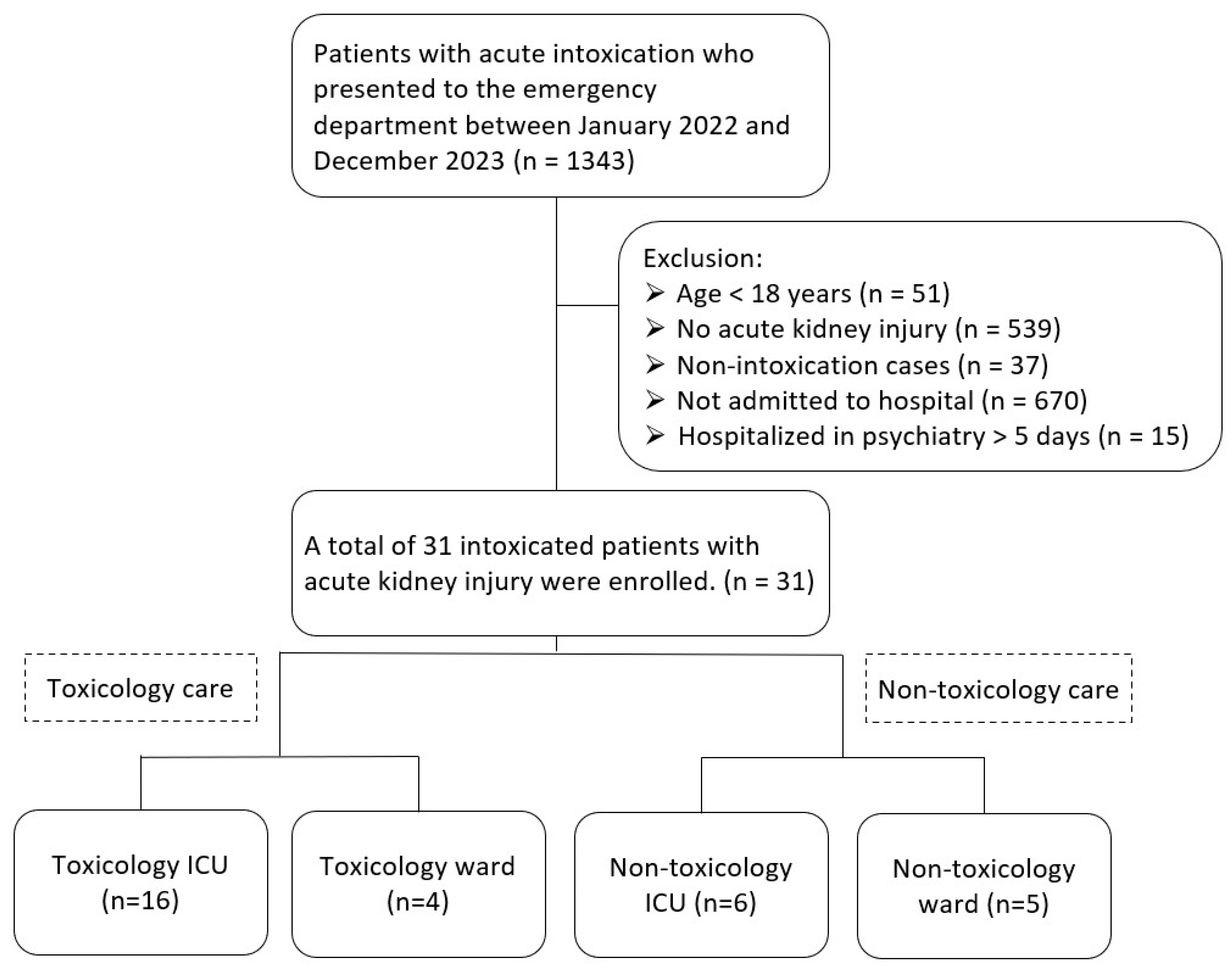

3.1. Patient Enrollment Flowchart

3.2. Types of Substances Causing Intoxication in Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Settings

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

3.4. Outcome

3.5. Comparative Analysis in Intoxicated Patients With or Without Acute Kidney Injury

3.6. Subgroup Analysis of Length of Stay and Mortality Rates by Age Groups (≤40 Years, 41–64 Years, ≥65 Years)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petejova, N.; Martinek, A.; Zadrazil, J.; Teplan, V. Acute toxic kidney injury. Ren. Fail. 2019, 41, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.-H.; Huang, L.-C.; Su, Y.-J. Poisoning-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: A Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso, J.A.R.; Silva, C.A.M.d. The nephrologist as a consultant for acute poisoning: Epidemiology of severe poisonings in the State of Rio Grande do Sul and techniques to enhance renal elimination. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2010, 32, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M.; Taghaddosinejad, F.; Salamaty, P.; Soroosh, D.; Ashraf, H.; Ebrahimi, M. Renal failure prevalence in poisoned patients. Nephro-Urol. Mon. 2014, 6, e11910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, S.; Carter, A.; Liu, Y.-H.; Humble, I.; Trott, N.; Jacups, S.; Little, M. The impact of the introduction of a toxicology service on the intensive care unit. Clin. Toxicol. 2019, 57, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-K.; Chan, Y.-L.; Su, T.-H. Incidence of intoxication events and patient outcomes in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based observational study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingsma, H.F.; Bottle, A.; Middleton, S.; Kievit, J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Marang-Van De Mheen, P.J. Evaluation of hospital outcomes: The relation between length-of-stay, readmission, and mortality in a large international administrative database. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S.; Murray, P.; Robin, J.; Wilkinson, P.; Fluck, D.; Fry, C.H. Evaluation of the association of length of stay in hospital and outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2022, 34, mzab160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Kerr, J.F.; Braitberg, G.; Louis, W.J.; O’Callaghan, C.J.; Frauman, A.G.; Mashford, M.L. Impact of a toxicology service on a metropolitan teaching hospital. Emerg. Med. 2001, 13, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.; Tsui, S.; Tong, H. The impact of an emergency department toxicology team in the management of acute intoxication. Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Chan, C.; Lau, F. Toxicology training unit in emergency department reduces admission to other specialties and hospital length of stay. Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.M.; Danagoulian, S.; Lynch, M.; Menke, N.; Mu, Y.; Saul, M.; Abesamis, M.; Pizon, A.F. The effect of a medical toxicology inpatient service in an academic tertiary care referral center. J. Med. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, S.C.; Brooks, D.E.; Skolnik, A.B.; Gerkin, R.D.; Glenn, S. Effect of a medical toxicology admitting service on length of stay, cost, and mortality among inpatients discharged with poisoning-related diagnoses. J. Med. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, R.G.; Little, M. Inpatient toxicology services improve resource utilization for intoxicated patients: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uges, D. What Is the Definition of a Poisoning? Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 8, pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.L.; Kellum, J.A.; Shah, S.V.; Molitoris, B.A.; Ronco, C.; Warnock, D.G.; Levin, A.; Network, A.K.I. Acute Kidney Injury Network: Report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit. Care 2007, 11, R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, H.E.; Sjöberg, G.K.; Haines, J.A.; de Garbino, J.P. Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovar, D.; Peyre, H.; Mégarbane, B. Relationship between acute kidney injury and mortality in poisoning–a systematic review and metanalysis. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, R.; Kellum, J.A.; Ronco, C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet 2012, 380, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.A.; Harel, Z.; McArthur, E.; Nash, D.M.; Acedillo, R.; Kitchlu, A.; Garg, A.X.; Chertow, G.M.; Bell, C.M.; Wald, R. Causes of death after a hospitalization with AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, N.M.; Kolhe, N.V.; McIntyre, C.W.; Monaghan, J.; Lawson, N.; Elliott, D.; Packington, R.; Fluck, R.J. Defining the cause of death in hospitalised patients with acute kidney injury. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoardi, K.Z.; Armitage, M.C.; Harris, K.; Page, C.B. Establishing a dedicated toxicology unit reduces length of stay of poisoned patients and saves hospital bed days. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2017, 29, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.J.; Han, K.S.; Song, J.; Lee, S.W. Comparison of the new-Poisoning Mortality Score and the Modified Early Warning Score for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with acute poisoning. Clin. Toxicol. 2024, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.S.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, E.J.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.W. Development and validation of new poisoning mortality score system for patients with acute poisoning at the emergency department. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, D. Emergency mortality of non-trauma patients was predicted by qSOFA score. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Chun, B.J.; Moon, J.M. The qSOFA score: A simple and accurate predictor of outcome in patients with glyphosate herbicide poisoning. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Moon, J.M.; Chun, B.J.; Lee, B.K. Use of qSOFA score in predicting the outcomes of patients with glyphosate surfactant herbicide poisoning immediately upon arrival at the emergency department. Shock 2019, 51, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Elmorsy, S.A. Evaluation of the new poisoning mortality score in comparison with PSS and SOFA scoring systems to predict mortality in poisoned patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 13, tfad113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substances | Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 20) | Non-Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 11) | Total (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines and Hypnotics | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Ethanol | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Antidepressants | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Antipsychotics | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Valacyclovir | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Carbon monoxide | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Morphine | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Amphetamines/psychoactive stimulants | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pesticide (Organophosphate) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Amlodipine | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Digoxin | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Baclofen | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Neutral detergent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Warfarin | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Metformin | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 20) | Non-Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD/N (%) | Mean ± SD/N (%) | p | |

| Age (years) | 62.4 ± 21.7 | 64.8 ± 21.3 | 0.767 |

| Male gender | 13 (65.0) | 5 (45.5) | 0.288 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.7 ± 2.2 | 4.3 ± 5.1 | 0.195 |

| eGFR | 21.6 ± 12 | 23.8 ± 15 | 0.398 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (25) | 4 (36.4) | 0.109 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (25) | 3 (27.3) | 0.727 |

| Hypertension | 11 (55) | 7 (63.6) | 0.455 |

| Mood disorder | 7 (35) | 2 (18.2) | 0.546 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (5) | 2 (18.2) | 0.586 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1 (5) | 1 (9.1) | 0.909 |

| Arrhythmia | 2 (10) | 1 (9.1) | 0.586 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | - |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | - |

| Renal function recovery | 12 (60) | 8 (72.7) | 0.356 |

| Tracheal intubation | 7 (35) | 5 (45.5) | 0.303 |

| Emergent hemodialysis | 8 (40) | 7 (63.6) | 0.167 |

| qSOFA score | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.151 |

| Poisoning severity score | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.092 |

| Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 20) | Non-Toxicology ICU/Ward (n = 11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD/N (%) | Mean ± SD/N (%) | p | |

| Length of stay in ICU (day) | 9.1 ± 10.5 | 8.8 ± 8.7 | 0.951 |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 15.0 ± 16.3 | 18.0 ± 24.3 | 0.679 |

| In-hospital mortality | 4 (20) | 1 (9.1) | 0.620 |

| Intoxicated Patients with AKI (n = 31) | Intoxicated Patients Without AKI (n = 539) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD/N (%) | Mean ± SD/N (%) | p | |

| Age (years) | 63.3 ± 21.2 | 47.2 ± 20.0 | <0.01 * |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 16.3 ± 19.2 | 5.5 ± 8.9 | <0.01 * |

| In-hospital mortality | 5 (16) | 10 (1.9) | <0.01 * |

| Intoxicated Patients with AKI (n = 31) | Intoxicated Patients Without AKI (n = 539) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD/N (%) | Mean ± SD/N (%) | p | |

| Age ≤ 40 (years) | 30.3 ± 3.9 | 28.4 ± 6.4 | 0.225 |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 37.5 ± 36.5 | 5.3 ± 11.1 | <0.01 * |

| In-hospital mortality | 0/4 (0) | 1/234 (0.4) | 0.983 |

| Age 41–64 (years) | 52.1 ± 9.3 | 51.6 ± 6.9 | 0.469 |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 12.6 ± 16.5 | 6.9 ± 9.8 | <0.05 * |

| In-hospital mortality | 2/12 (16.7) | 0/176 (0) | <0.01 * |

| Age ≥ 65 (years) | 80.4 ± 11.8 | 75.6 ± 7.4 | 0.081 |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 13.6 ± 12 | 10.6 ± 16 | <0.05 * |

| In-hospital mortality | 3/15 (20) | 9/129 (6.3) | 0.076 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, C.-S.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, W.-K.; Mu, H.-W.; Yang, K.-W.; Yu, J.-H. A Comparative Analysis of Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Care in Intoxicated Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Medicina 2024, 60, 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121997

Pan C-S, Chen C-H, Chen W-K, Mu H-W, Yang K-W, Yu J-H. A Comparative Analysis of Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Care in Intoxicated Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Medicina. 2024; 60(12):1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121997

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Chi-Syuan, Chun-Hung Chen, Wei-Kung Chen, Han-Wei Mu, Kai-Wei Yang, and Jiun-Hao Yu. 2024. "A Comparative Analysis of Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Care in Intoxicated Patients with Acute Kidney Injury" Medicina 60, no. 12: 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121997

APA StylePan, C.-S., Chen, C.-H., Chen, W.-K., Mu, H.-W., Yang, K.-W., & Yu, J.-H. (2024). A Comparative Analysis of Toxicology and Non-Toxicology Care in Intoxicated Patients with Acute Kidney Injury. Medicina, 60(12), 1997. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60121997