Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

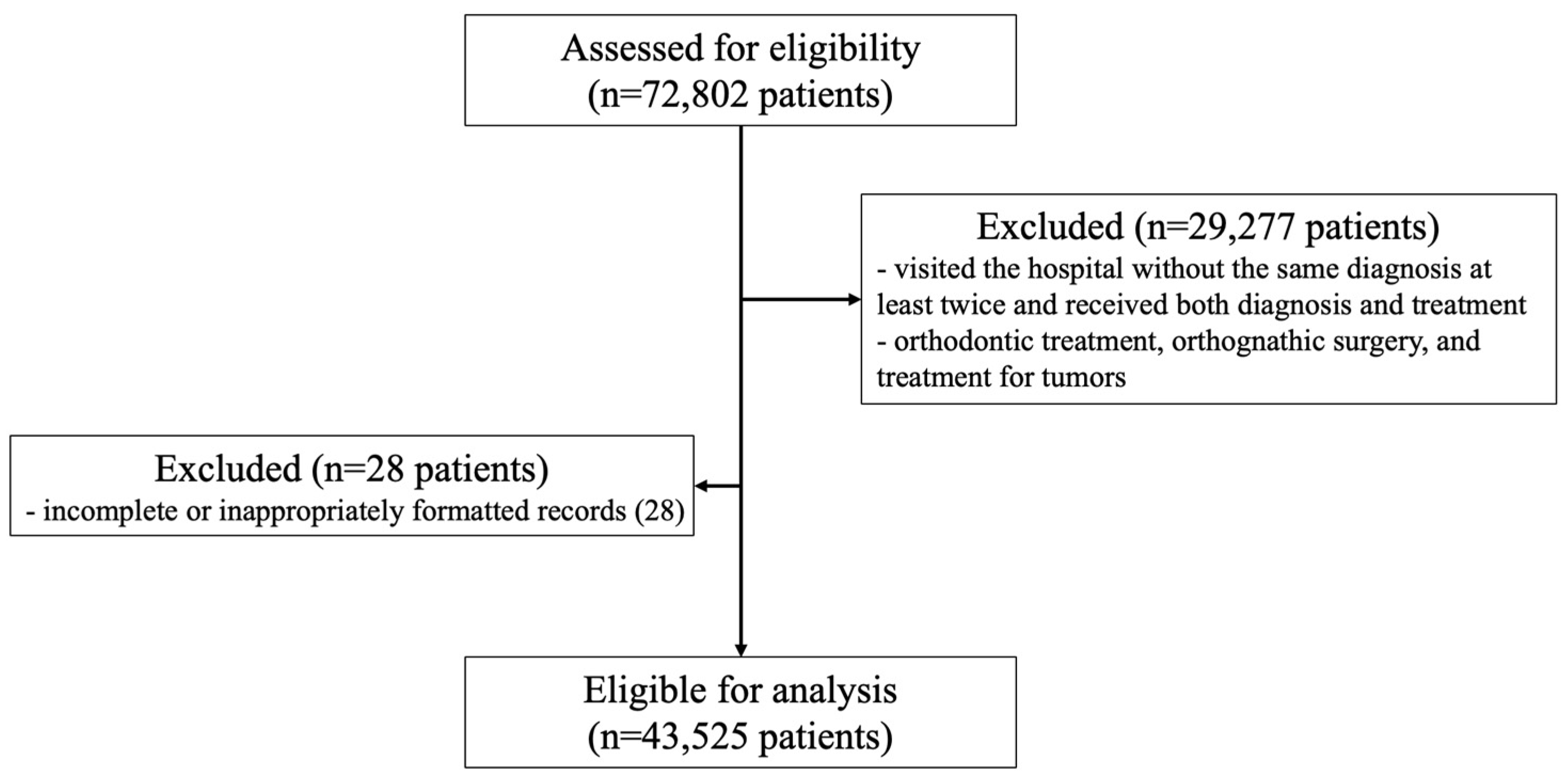

2.1. Patient Survey Overview and Study Subjects

2.2. Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

2.3. Definition of Simple and Complex Systemic Diseases

2.4. Analysis of the Relationship between Systemic Diseases and Dental Diseases

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seitz, M.W.; Listl, S.; Bartols, A.; Schubert, I.; Blaschke, K.; Haux, C.; Van Der Zande, M.M. Current Knowledge on Correlations Between Highly Prevalent Dental Conditions and Chronic Diseases: An Umbrella Review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabharwal, A.; Stellrecht, E.; Scannapieco, F.A. Associations between dental caries and systemic diseases: A scoping review. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.E.; Park, Y.G.; Han, K.; Min, J.; Kim, S. Association between dental pain and depression in Korean adults using the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobili, A.; Garattini, S.; Mannucci, P.M. Multiple diseases and polypharmacy in the elderly: Challenges for the internist of the third millennium. J. Comorb. 2011, 1, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, C.M.; Darer, J.; Boult, C.; Fried, L.P.; Boult, L.; Wu, A.W. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: Implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005, 294, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, L.G.; Valderas, J.M.; Healy, P.; Burke, E.; Newell, J.; Gillespie, P.; Murphy, A.W. The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Fam. Pract. 2011, 28, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sh, J. The Relationship between Oral Health and Diabetes Analyzed Using a Tooth Life Curve; Yonsei University: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.H.; Suh, I.; Nam, J.M.; Oh, D.K.; Son, H.K.; Kwon, H.K. Associations of missing teeth with medical status. J. Korean Acad. Oral Health 2002, 26, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.W.; Borgnakke, W.S. Periodontal disease: Associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-H. Chewing difficulty and multiple chronic conditions in Korean elders: KNHANES IV. J. Korean Dent. Assoc. 2013, 51, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrihari, T.G.; Vasudevan, V.; Manjunath, V.; Devaraju, D. Potential Co-Relation Between Chronic Periodontitis And Cancer—An Emerging Concept. Gulf J. Oncol. 2016, 1, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.E.; Park, Y.G.; Han, K.; Kim, S.Y. Association between dental pain and tooth loss with health-related quality of life: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey: A population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016, 95, e4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-E.; Park, Y.-G.; Han, K.; Min, J.-A.; Kim, S.-Y. Dental pain related to quality of life and mental health in South Korean adults. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyke, T.E.; Sheilesh, D. Risk factors for periodontitis. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2005, 7, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Genco, R.J.; Schifferle, R.E.; Dunford, R.G.; Falkner, K.L.; Hsu, W.C.; Balukjian, J. Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: A field trial. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2014, 145, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutger Persson, G. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis-inflammatory and infectious connections. Review of the literature. J. Oral Microbiol. 2012, 4, 11829. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar-Samtani, M.; Heaton, L.J.; Kelly, A.L.; Taylor, S.D.; Vidone, L.; Tranby, E.P. Periodontal treatment associated with decreased diabetes mellitus-related treatment costs: An analysis of dental and medical claims data. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 283–292.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnaud, C.; Thomas, F.; Pannier, B.; Danchin, N.; Bouchard, P. Oral Health and Blood Pressure: The IPC Cohort. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 28, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.A.; Tsakos, G.; Barbato, P.R.; Silva, D.A.S.; Peres, K.G. Tooth loss is associated with increased blood pressure in adults--a multidisciplinary population-based study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, S.-H.; Min, C.; Choi, H.-G.; Hong, S.-J. Increased Risk of Temporomandibular Joint Disorder in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Longitudinal Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shwaikh, H.; Urtane, I.; Pirttiniemi, P.; Pesonen, P.; Krisjane, Z.; Jankovska, I.; Davidsone, Z.; Stanevica, V. Radiologic features of temporomandibular joint osseous structures in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Cone beam computed tomography study. Stomatologija 2016, 18, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- González-Chávez, S.A.; Pacheco-Tena, C.; Caraveo-Frescas, T.d.J.; Quiñonez-Flores, C.M.; Reyes-Cordero, G.; Campos-Torres, R.M. Oral health and orofacial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtoglu, C.; Kurkcu, M.; Sertdemir, Y.; Ozbek, S.; Gürbüz, C. Temporomandibular disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A clinical study. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2016, 19, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Chang, S.; Pi, X.; Hua, F.; Jiang, H.; Liu, C.; Du, M. The Effect of Periodontitis on Dementia and Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delwel, S.; Binnekade, T.T.; Perez, R.S.G.M.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Scherder, E.J.A.; Lobbezoo, F. Oral health and orofacial pain in older people with dementia: A systematic review with focus on dental hard tissues. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Hsu, S.-W.; Yen, Y.-Y.; Lan, S.-J. Association of oral health-related quality of life and Alzheimer disease: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, M.; Straka-Trapezanlidis, M.; Deglovic, J.; Varga, I. Periodontitis and osteoporosis. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2015, 36, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Penoni, D.C.; Torres, S.R.; Farias, M.L.F.; Fernandes, T.M.; Luiz, R.R.; Leão, A.T.T. Association of osteoporosis and bone medication with the periodontal condition in elderly women. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.J.; Migliorati, C.A. Osteoporosis and its implications for dental patients. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, M.; Giordano, F.; Sangiovanni, G.; Capuano, N.; Acerra, A.; D’ambrosio, F. The Interaction between the Oral Microbiome and Systemic Diseases: A Narrative Review. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 1862–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Minty, M.; Vinel, A.; Canceill, T.; Loubières, P.; Burcelin, R.; Kaddech, M.; Blasco-Baque, V.; Laurencin-Dalicieux, S. Oral Microbiota: A Major Player in the Diagnosis of Systemic Diseases. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Systemic Diseases | Dental Diseases |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | Dental caries |

| Hypertension | Periodontal disease |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Pulp necrosis |

| Osteoporosis | Tooth loss |

| Dementia | Temporomandibular joint disorder |

| Others (dental diseases other than those mentioned above) |

| N (Total 43,525) | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

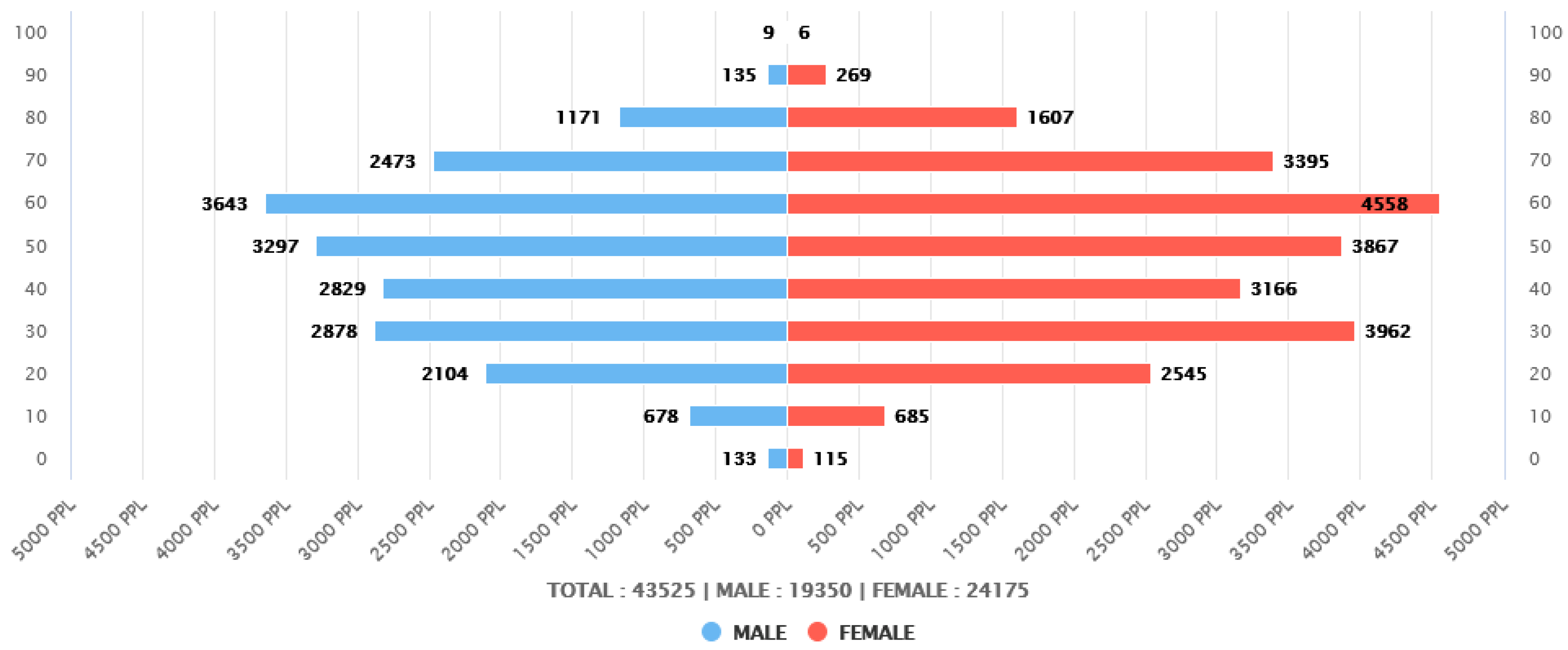

| sex | Male | 19,350 | 44.46 |

| Female | 24,175 | 55.54 | |

| age | 20–29 | 4649 | 10.68 |

| 30–39 | 6840 | 15.72 | |

| 40–49 | 5995 | 13.77 | |

| 50–59 | 7164 | 16.46 | |

| 60–69 | 8201 | 18.84 | |

| 70–79 | 5868 | 13.48 | |

| ≥80 | 3198 | 7.35 |

| Total N | Dental Caries | Periodontal Disease | Pulp Necrosis | Tooth Loss | TMJ Disorder | Others | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

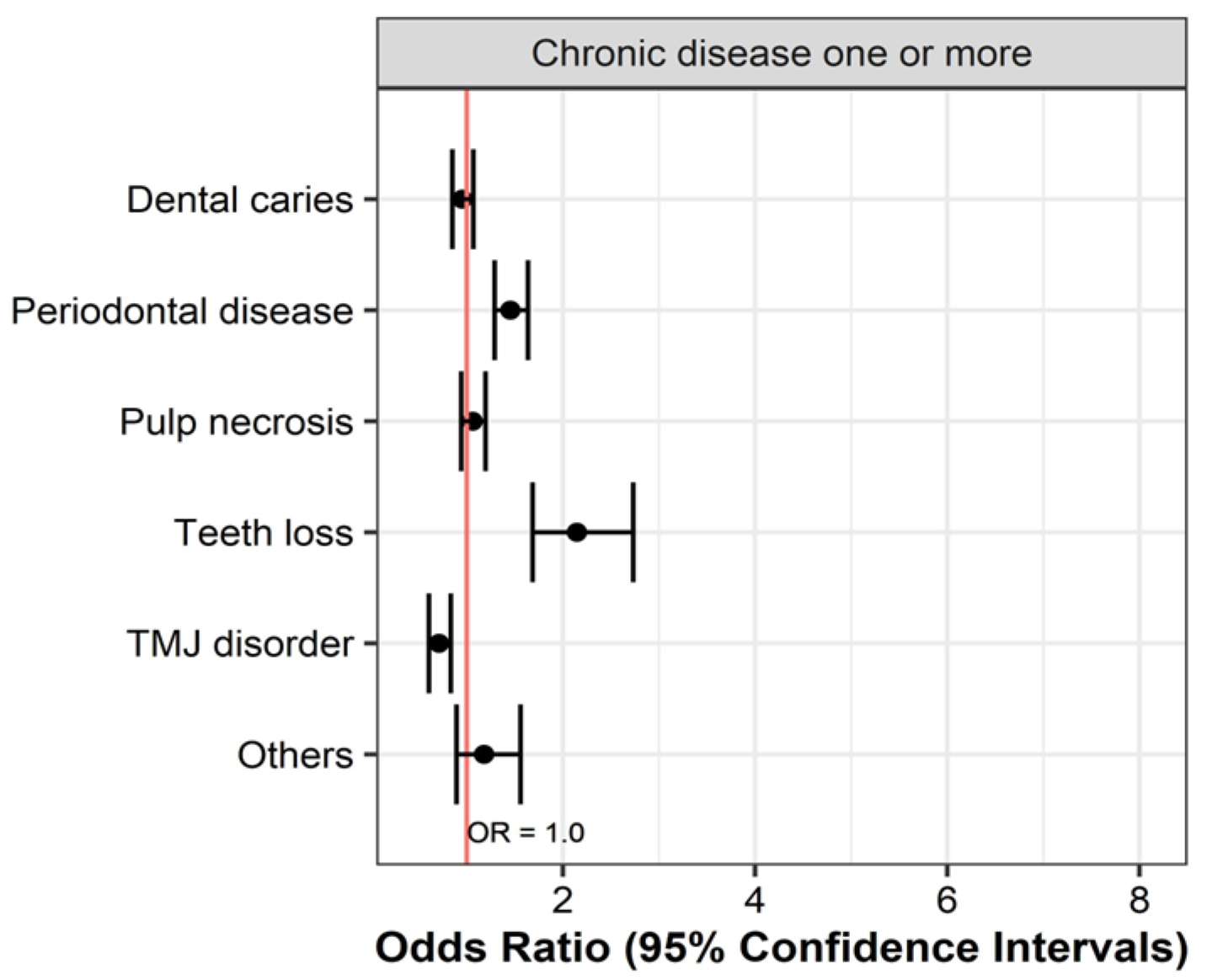

| Chronic disease one or more | Yes | 14,111 | 5241 (37.1) | 10,497 (74.4) | 4735 (33.6) | 1530 (10.8) | 1531 (10.8) | 680 (4.8) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 0.953 (0.850–1.068) | 1.454 (1.290–1.637) | 1.061 (0.942–1.195) | 2.146 (1.685–2.732) | 0.711 (0.606–0.834) | 1.180 (0.893–1.559) | ||

| p value | 0.406 | <0.001 | 0.332 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.244 | ||

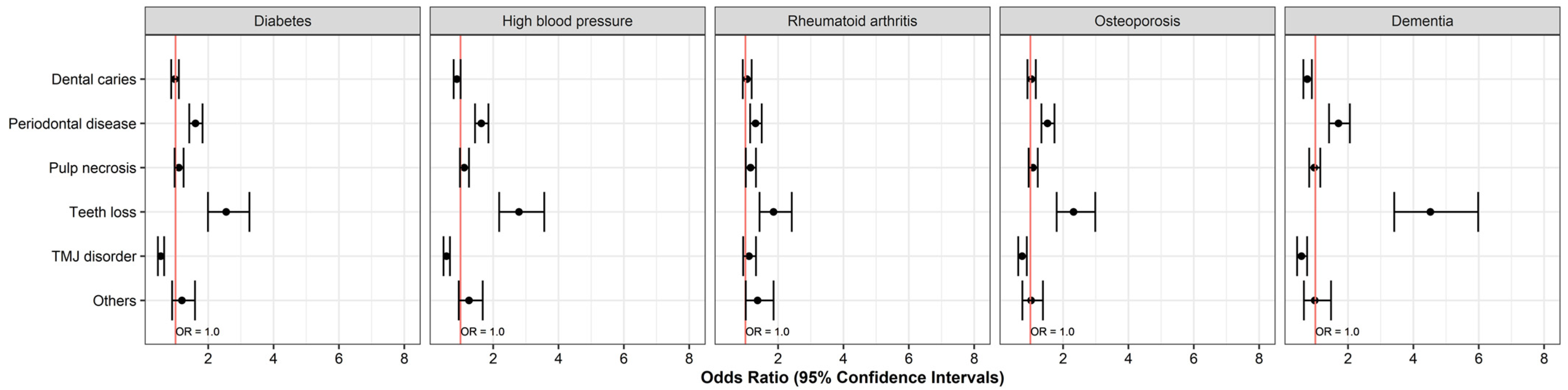

| Diabetes (DM) | Yes | 6828 | 2577 (37.7) | 5209 (76.3) | 2348 (34.4) | 862 (12.6) | 585 (8.6) | 333 (4.9) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 0.977 (0.867–1.102) | 1.610 (1.420–1.826) | 1.101 (0.972–1.246) | 2.549 (1.992–3.261) | 0.547 (0.460–0.651) | 1.195 (0.895–1.595) | ||

| p value | 0.708 | <0.001 | 0.130 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.227 | ||

| High blood pressure (HBP) | Yes | 7478 | 2660 (35.6) | 5727 (76.6) | 2591 (34.6) | 1021 (13.7) | 666 (8.9) | 384 (5.1) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 0.890 (0.791–1.003) | 1.637 (1.445–1.855) | 1.114 (0.984–1.260) | 2.790 (2.184–3.564) | 0.571 (0.481–0.677) | 1.261 (0.947–1.680) | ||

| p value | 0.055 | <0.001 | 0.087 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.111 | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | Yes | 3418 | 1345 (39.4) | 2473 (72.4) | 1214 (35.5) | 326 (9.5) | 546 (16) | 190 (5.6) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.046 (0.919–1.190) | 1.310 (1.145–1.499) | 1.157 (1.012–1.322) | 1.860 (1.432–2.418) | 1.110 (0.931–1.323) | 1.372 (1.011–1.861) | ||

| p value | 0.494 | <0.001 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 0.245 | 0.041 | ||

| Osteoporosis (OPR) | Yes | 4688 | 1828 (39) | 3529 (75.3) | 1590 (33.9) | 545 (11.6) | 532 (11.3) | 197 (4.2) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.031 (0.910–1.166) | 1.524 (1.338–1.737) | 1.078 (0.947–1.226) | 2.321 (1.804–2.986) | 0.747 (0.628–0.890) | 1.022 (0.755–1.384) | ||

| p value | 0.635 | <0.001 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.887 | ||

| Dementia (DMT) | Yes | 1015 | 323 (31.8) | 785 (77.3) | 320 (31.5) | 207 (20.4) | 91 (9) | 41 (4) |

| No | 1361 | 521 (38.3) | 907 (66.6) | 439 (32.3) | 73 (5.4) | 199 (14.6) | 56 (4.1) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 0.753 (0.634–0.893) | 1.708 (1.419–2.056) | 0.967 (0.812–1.151) | 4.520 (3.414–5.983) | 0.575 (0.442–0.748) | 0.981 (0.650–1.480) | ||

| p value | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.706 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.927 | ||

| Complex disease (DM) | Simple | 1981 | 686 (34.6) | 1266 (63.9) | 547 (27.6) | 123 (6.2) | 154 (7.8) | 78 (3.9) |

| Complex | 4847 | 1726 (35.6) | 3642 (75.1) | 1677 (34.6) | 670 (13.8) | 385 (7.9) | 220 (4.5) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.044 (0.935–1.165) | 1.707 (1.525–1.910) | 1.387 (1.236–1.556) | 2.423 (1.984–2.959) | 1.024 (0.843–1.244) | 1.160 (0.891–1.510) | ||

| p value | 0.442 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.814 | 0.270 | ||

| Complex disease (HBP) | Simple | 2415 | 702 (29.1) | 1534 (63.5) | 698 (28.9) | 188 (7.8) | 213 (8.8) | 114 (4.7) |

| Complex | 5063 | 1767 (34.9) | 3816 (75.4) | 1739 (34.3) | 742 (14.7) | 396 (7.8) | 225 (4.4) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.308 (1.178–1.454) | 1.758 (1.582–1.952) | 1.287 (1.158–1.430) | 2.034 (1.719–2.406) | 0.877 (0.737–1.044) | 0.939 (0.745–1.182) | ||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.140 | 0.591 | ||

| Complex disease (RA) | Simple | 1308 | 352 (26.9) | 616 (47.1) | 335 (25.6) | 30 (2.3) | 221 (16.9) | 44 (3.4) |

| Complex | 2110 | 828 (39.2) | 1549 (73.4) | 743 (35.2) | 242 (11.5) | 262 (12.4) | 102 (4.8) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.754 (1.510–2.038) | 3.102 (2.683–3.586) | 1.579 (1.355–1.840) | 5.519 (3.751–8.117) | 0.697 (0.574–0.847) | 1.459 (1.017–2.092) | ||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.039 | ||

| Complex disease (OPR) | Simple | 1430 | 497 (34.8) | 900 (62.9) | 388 (27.1) | 69 (4.8) | 156 (10.9) | 39 (2.7) |

| Complex | 3258 | 1231 (37.8) | 2392 (73.4) | 1112 (34.1) | 422 (13) | 342 (10.5) | 140 (4.3) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.140 (1.001–1.298) | 1.627 (1.425–1.857) | 1.392 (1.213–1.597) | 2.935 (2.257–3.815) | 0.958 (0.783–1.170) | 1.602 (1.116–2.296) | ||

| p value | 0.048 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.674 | <0.001 | ||

| Complex disease (DMT) | Simple | 211 | 56 (26.5) | 133 (63) | 50 (23.7) | 23 (10.9) | 12 (5.7) | 7 (3.3) |

| Complex | 804 | 255 (31.7) | 601 (74.8) | 256 (31.8) | 166 (20.6) | 76 (9.5) | 30 (3.7) | |

| OR (95% CIs) | 1.286 (0.915–1.806) | 1.736 (1.259–2.394) | 1.504 (1.060–2.136) | 2.127 (1.335–3.387) | 1.731 (0.923–3.248) | 1.130 (0.489–2.609) | ||

| p value | 0.147 | <0.001 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.084 | 0.775 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kahm, S.H.; Yang, S. Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population. Medicina 2024, 60, 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101693

Kahm SH, Yang S. Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population. Medicina. 2024; 60(10):1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101693

Chicago/Turabian StyleKahm, Se Hoon, and SungEun Yang. 2024. "Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population" Medicina 60, no. 10: 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101693

APA StyleKahm, S. H., & Yang, S. (2024). Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population. Medicina, 60(10), 1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101693