Groin Hernia Repair during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Romanian Nationwide Analysis

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

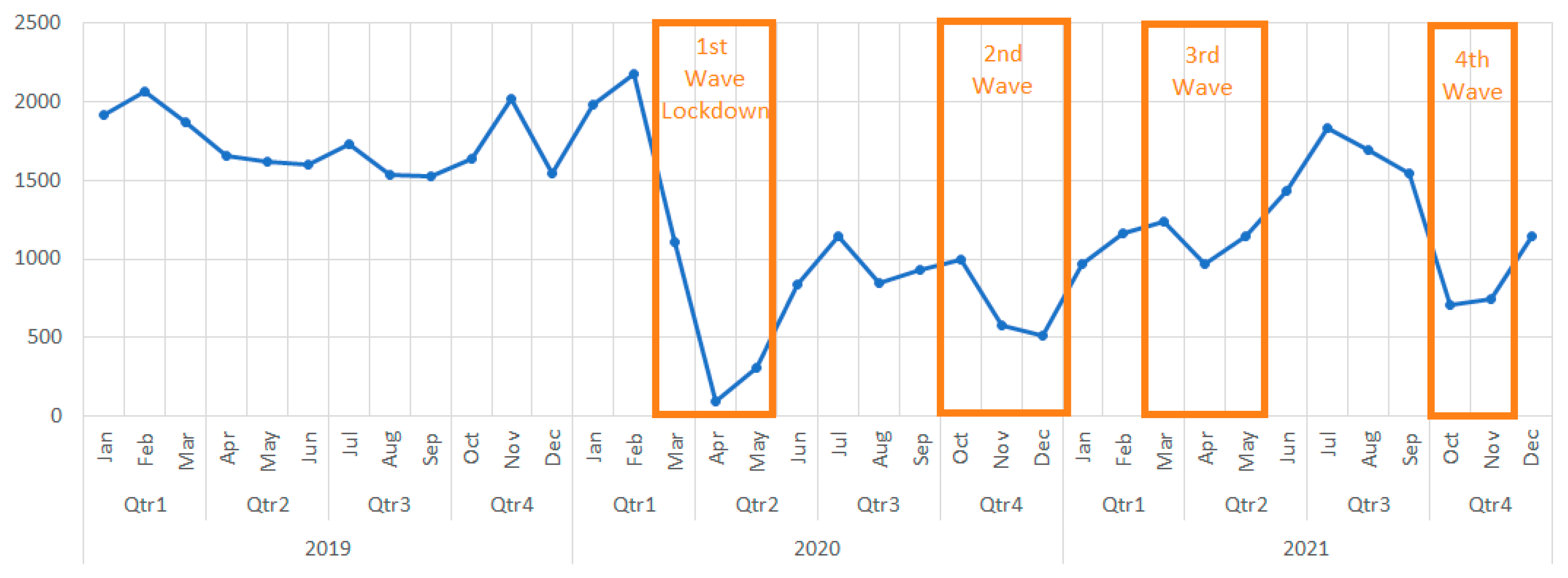

3.2. The Evolution of Cases during the Pandemic—Total Cases

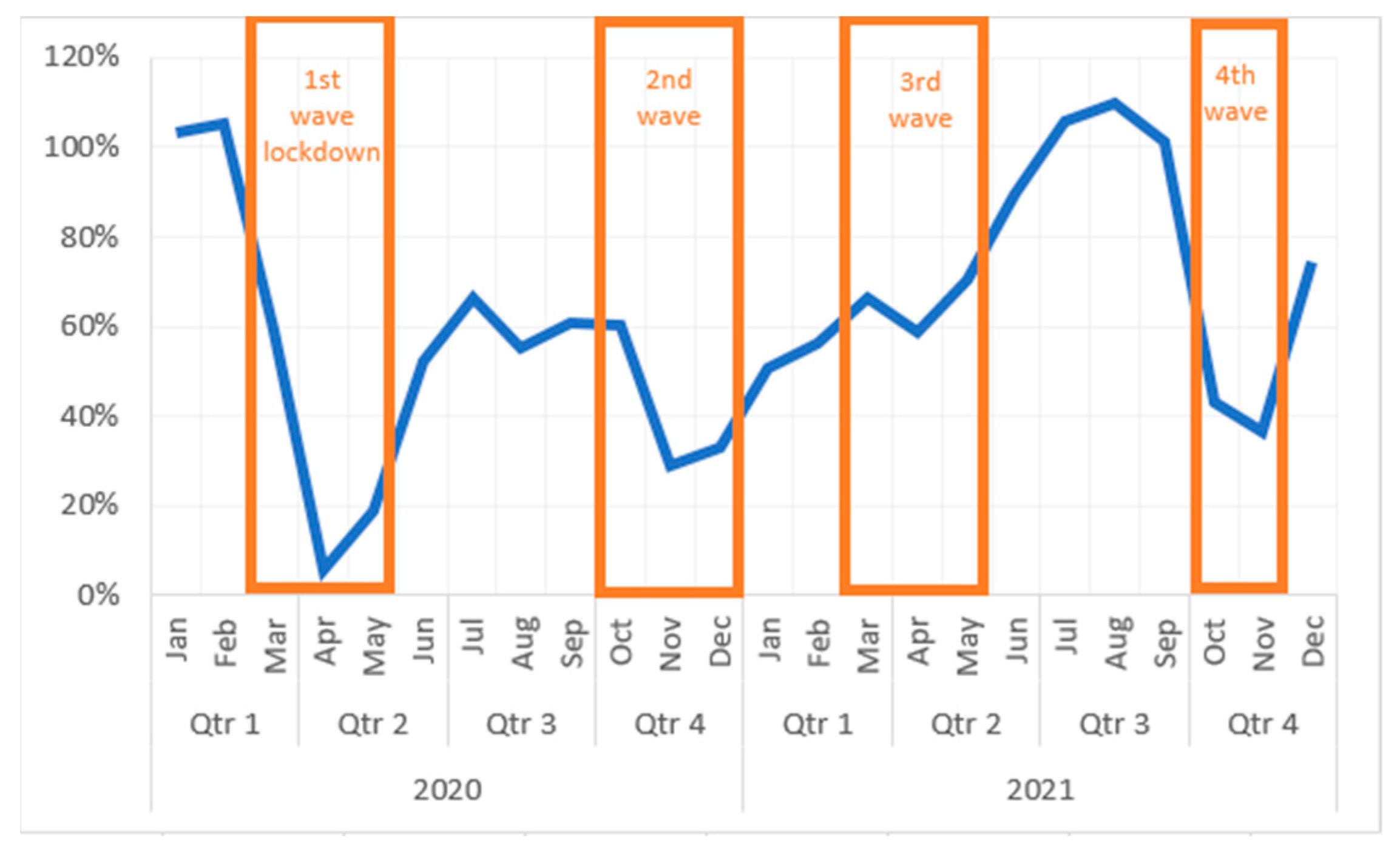

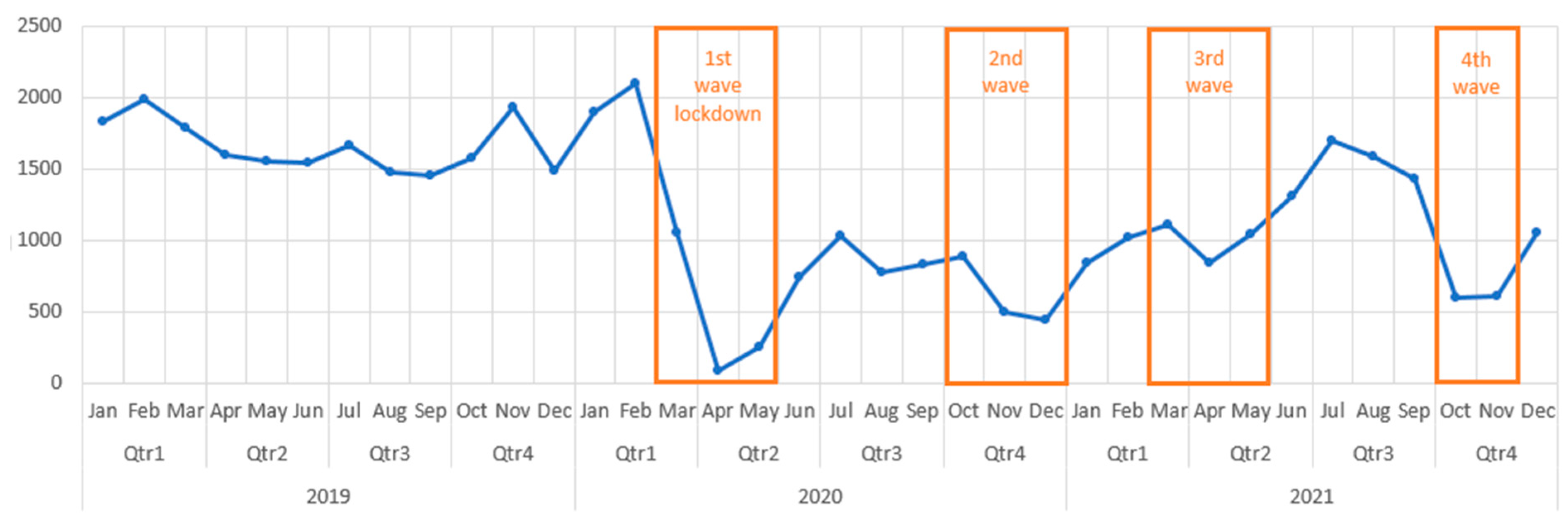

3.3. The Evolution of Cases during the Pandemic—Public vs. Private Hospitals

3.4. Mean Admission Period—PbH vs. PvH

3.5. Classic vs. Laparoscopic

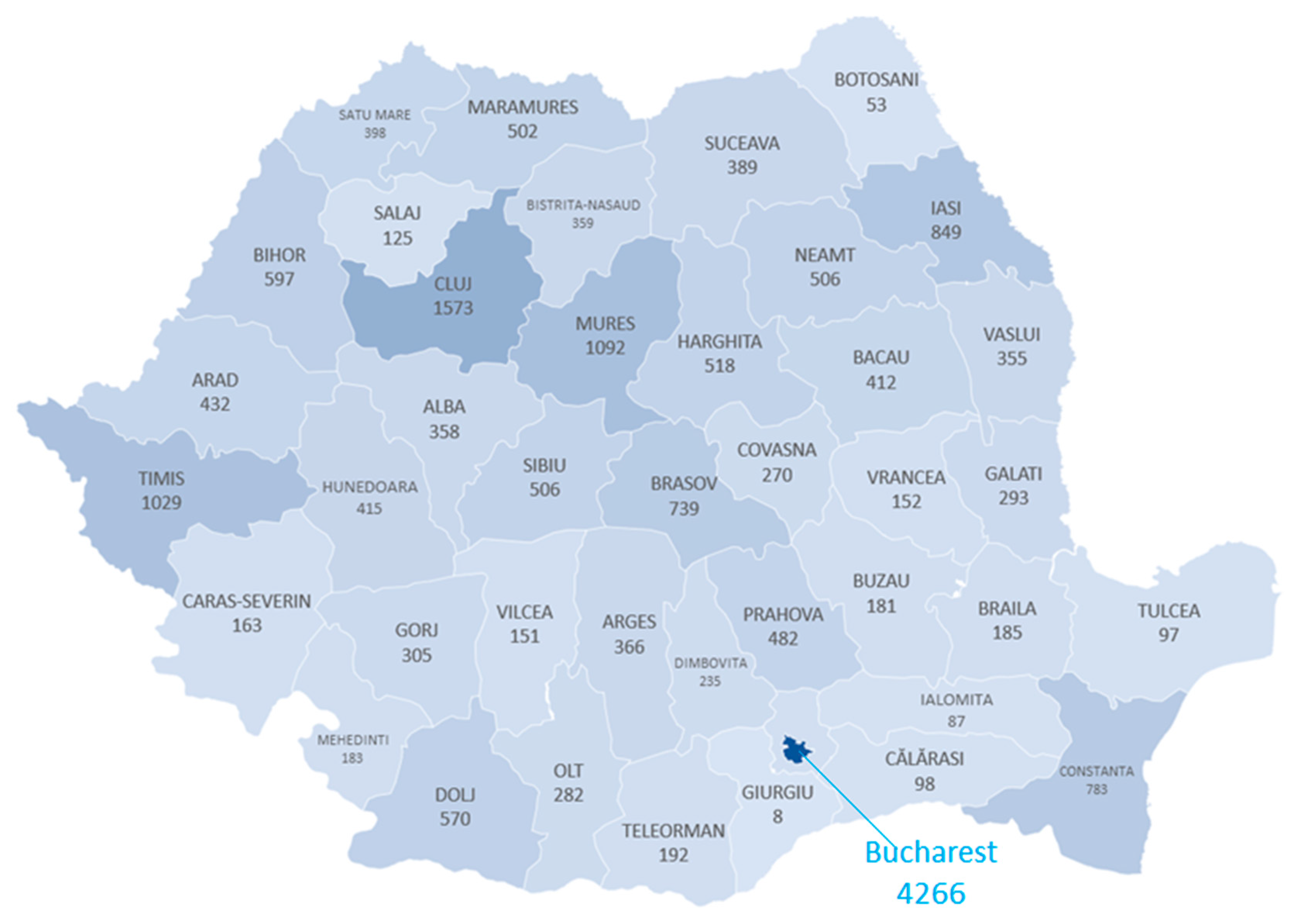

3.6. Geographic Distribution

3.7. Comorbidities and Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- COVID-19 Data Explorer—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer?facet=none&Metric=Confirmed+deaths&Interval=7-day+rolling+average&Relative+to+Population=true&Color+by+test+positivity=false&country=~ROU (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Weeks, W.B.; Paraponaris, A.; Ventelou, B. Geographic variation in rates of common surgical procedures in France in 2008-2010, and comparison to the US and Britain. Health Policy 2014, 118, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, E.J.; Feinglass, J.M.; Joung, R.H.S.; Odell, D.D. Statewide Examination of Access to Cancer Surgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 286, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulacoglu, H. Current options in inguinal hernia repair in adult patients. Hippokratia 2011, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Surgical Operations and Procedures Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Surgical_operations_and_procedures_statistics&oldid=561105#Number_of_surgical_operations_and_procedures (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Primatesta, P.; Goldacre, M.J. Inguinal Hernia Repair: Incidence of Elective and Emergency Surgery, Readmission and Mortality. Int. J. Epidemiol. O Int. Epktemlologlcal Assoc. 1996, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivusalo, A.I. Inguinal Hernia. In Rickham’s Neonatal Surgery; Losty, P., Flake, A., Rintala, R., Hutson, J., Lwai, N., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, K.; Wennberg, J.E.; Hovind, O.B.; Clifford, P. Small-Area Variations in the Use of Common Surgical Procedures: An International Comparison of New England, England, and Norway. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 307, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkow, I.M. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 83, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.P.; Chiriac, D.N.; Vladescu, C. Changing patient classification system for hospital reimbursement in Romania. Croat. Med. J. 2010, 51, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Country, E.U.; Profile, H. OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; Country Health Profile 2021; State of Health in the EU, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Boghdady, M.; Ewalds-Kvist, B.M. Laparoscopic Surgery and the debate on its safety during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of recommendations. Surgeon 2021, 19, e29–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, N.; Dort, J.; Cho, E.; Feldman, L.; Keller, D.; Lim, R.; Mikami, D.; Phillips, E.; Spaniolas, K.; Tsuda, S.; et al. SAGES and EAES recommendations for minimally invasive surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 2327–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; Nepogodiev, D.; Bhangu, A. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: Global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Hojaij, F.C.; Chinelatto, L.A.; Boog, G.H.P.; Kasmirski, J.A.; Lopes, J.V.Z.; Sacramento, F.M. Surgical Practice in the Current COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review. Clinics 2020, 75, e1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uimonen, M.; Kuitunen, I.; Paloneva, J.; Launonen, A.P.; Ponkilainen, V.; Mattila, V.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on waiting times for elective surgery patients: A multicenter study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algera, M.; van Driel, W.; Slangen, B.; Kruitwagen, R.; Wouters, M.; Baalbergen, A.; Cate, A.T.; Aalders, A.; van der Kolk, A.; Kruse, A.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19-pandemic on patients with gynecological malignancies undergoing surgery: A Dutch population-based study using data from the ‘Dutch Gynecological Oncology Audit’. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.F.; Wang, K.Y.; Ippolito, B.N.; Ficke, J.R.; Jain, A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Elective Inpatient Surgical Admissions: Evidence From Maryland. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 268, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medas, F.; Luca, G.; Nicola, A.; Giancarlo, A.; Marco, B.; Marco, B. The THYCOVIT (Thyroid Surgery during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy) study: Results from a nationwide, multicentric, case-controlled study. Updates Surg. 2021, 73, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Mian, M.; Sreedharan, S.; Kahokehr, A.A. The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on elective urological procedures in Australia. Asian J. Urol. 2022, 9, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.M.; Favorito, L.A.; Henriques, J.V.T.; Canalini, A.F.; Anzolch, K.M.J.; Fernandes, R.D.C.; Bellucci, C.H.S.; Silva, C.S.; Wroclawski, M.L.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on clinical practice, income, health and lifestyle behavior of Brazilian urologists. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2020, 46, 1042–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Since January 2020 Elsevier Has Created a COVID-19 Resource Centre with Free Information in English and Mandarin on the Novel Coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 Resource Centre Is Hosted on Elsevier Connect, the Company’s Public News and Information. no. January. 2020. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370576118741734285 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Boyarsky, B.J.; Chiang, T.P.-Y.; Werbel, W.A.; Durand, C.M.; Avery, R.K.; Getsin, S.N.; Jackson, K.R.; Kernodle, A.B.; Rasmussen, S.E.V.P.; Massie, A.B.; et al. Early impact of COVID-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, S.; Berry, J.A.; Berry, D.K.; Marotta, D.A.; Buckley, S.E.; Javaid, R.; Jacqueline, D.M.; Magargee, C.E.; Ferrouge, L.M.; Rogalska, A.M.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Resident Physicians Well-Being in the Surgical and Primary Care Specialties in the United States and Canada. Cureus 2021, 13, e19677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Awuah, W.A.; Ng, J.C.; Kundu, M.; Yarlagadda, R.; Sen, M.; Nansubuga, E.P.; Abdul-Rahman, T.; Hasan, M.M. Elective surgeries during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Case burden and physician shortage concerns. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenbecher, F.; Scheller-Kreinsen, D.; Röttger, J.; Busse, R. Comparison of hospital costs and length of stay associated with open-mesh, totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair, and transabdominal preperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: An analysis of observational data using propensity score matching. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, R.F.; de Adana Belbel, J.C.R.; Morales, F.A.; Septiem, J.G.; Lucas, F.J.M.; Esteban, M.L. Cost–Benefit Analysis Comparing Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hernia Repair. Cirugía Española 2014, 92, 553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Van Veenendaal, N.; Simons, M.P.; Bonjer, H.J. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 2018, 22, 167–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoescu, S.; Patrascu, T.; Brezean, I. Predictors for length of hospital stay after inguinal hernia surgery. J. Med. Life 2015, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elmessiry, M.M.; Gebaly, A.A. Laparoscopic versus open mesh repair of bilateral primary inguinal hernia: A three-armed Randomized controlled trial. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 59, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dwyer, P.J. Current status of the debate on laparoscopic hernia repair. Br. Med. Bull. 2004, 70, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, K.S.; Nagendran, M.; Toon, C.D.; Davidson, B.R. Laparoscopic surgical box model training for surgical trainees with limited prior laparoscopic experience. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD010478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle-Leinhase, I.; Köckerling, F.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Montgomery, A.; Gillion, J.F.; Rodriguez, J.A.P.; Hope, W.; Muysoms, F. Comparison of hernia registries: The CORE project. Hernia 2018, 22, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouws, J.; Nel, D.; Bougard, H.C.; Sofianos, C.; Reimers, G.B.; Rayamajhi, S.; Folscher, D.J.; de Beer, R.; Rademan, R.J.; Donkin, I.E.; et al. Building a national hernia registry in South Africa: Initial ventral hernia repair results from a diverse healthcare sector. Hernia 2021, 25, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, A.S.; McFadyen, R.; Hodge, K.; Grossart, C.M.; East, B.; de Beaux, A.C. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Hernia Surgery: The South-East Scotland Experience. Cureus 2022, 14, e29532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.L.; Pereira, X.; Dos Santos, D.C.; Camacho, D.; Malcher, F. Where are the hernias? A paradoxical decrease in emergency hernia surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Hernia 2020, 24, 1141–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11). 2022. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Grand Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Surgical Interventions | 20,722 | 11,510 | 14,563 | 46,795 | |

| Inguinal Hernia | 19,955 (96.3) | 11,055 (96) | 14,010 (96.2) | 45,020 (96.2) | |

| Femoral Hernia | 767 (3.7) | 455 (4) | 553 (3.8) | 1775 (3.8) | |

| Bilateral Hernia Diagnoses | 1457 (7) | 971 (8.4) | 1176 (8.1) | 3604 (7.7) | |

| Simultaneous Bilateral Hernia Repair | 903 (4.4) | 606 (5.3) | 775 (5.3) | 2284 (4.9) | |

| Complications | |||||

| Irreducible/ Incarcerated | 5662 (27.3) | 3590 (31.2) | 4619 (31.7) | 13,871 (29.6) | |

| Strangulated | 185 (0.893) | 98 (0.851) | 150 (1.03) | 433 (0.925) | |

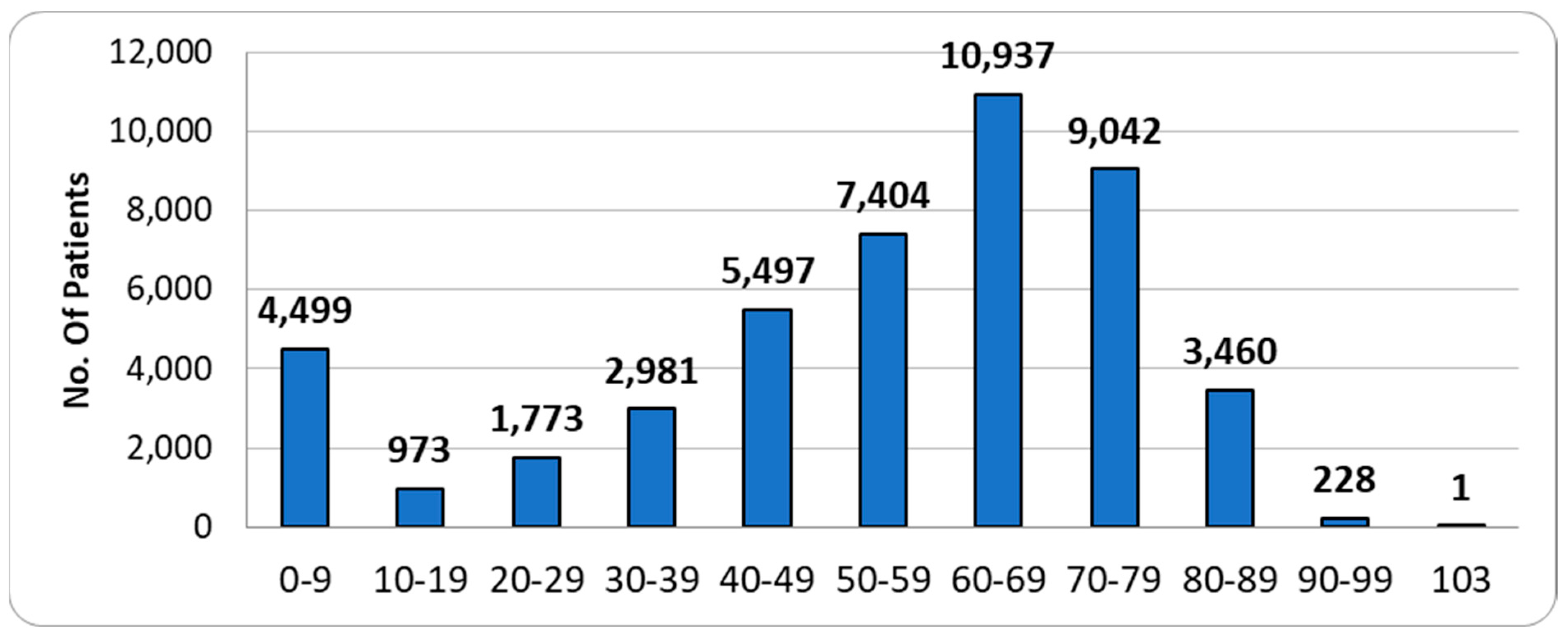

| Age | |||||

| 0–9 | 1926 (9.3) | 1068 (9.3) | 1505 (10.3) | 4499 (9.6) | |

| 10–19 | 457 (2.2) | 208 (1.8) | 308 (2.1) | 973 (2.1) | |

| 20–29 | 779 (3.8) | 441 (3.8) | 553 (3.8) | 1773 (3.8) | |

| 30–39 | 1304 (6.3) | 760 (6.6) | 917 (6.3) | 2981 (6.4) | |

| 40–49 | 2391 (11.5) | 1393 (12.1) | 1713 (11.8) | 5497 (11.7) | |

| 50–59 | 3162 (15.3) | 1873 (16.3) | 2369 (16.3) | 7404 (15.8) | |

| 60–69 | 4976 (24) | 2692 (23.4) | 3269 (22.4) | 10,937 (23.4) | |

| 70–79 | 4036 (19.5) | 2188 (19) | 2818 (19.4) | 9042 (19.3) | |

| 80–89 | 1578 (7.6) | 836 (7.3) | 1046 (7.2) | 3460 (7.4) | |

| 90–99 | 112 (0.5) | 51 (0.4) | 65 (0.4) | 228 (0.5) | |

| 103 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| F | 2796 (13.5) | 1490 (12.9) | 1870 (12.8) | 6156 (13.2) | |

| M | 17,926 (86.5) | 10,020 (87.1) | 12,693 (87.2) | 40,639 (86.8) | |

| Procedure | |||||

| Classic | 17,965 (86.7) | 9668 (84) | 12,051 (82.8) | 39,684 (84.8) | |

| Classic bilateral | 537 (2.6) | 283 (2.5) | 382 (2.6) | 1202 (2.6) | |

| Laparoscopic | 2757 (13.3) | 1842 (16) | 2512 (17.2) | 7111 (15.2) | |

| Laparoscopic bilateral | 366 (1.8) | 323 (2.8) | 393 (2.7) | 1082 (2.3) | |

| Relapsed hernia | 1443 (7.0) | 901 (7.8) | 1110 (7.6) | 3454 (7.4) | |

| Hospital | |||||

| Private | 843 (4.1) | 946 (8.2) | 1435 (9.9) | 3224 (6.9) | |

| Public | 19,879 (95.9) | 10,564 (91.8) | 13,128 (90.1) | 43,571 (93.1) | |

| Outcome | |||||

| Death | 59 (0.285) | 43 (0.374) | 60 (0.412) | 162 (0.346) |

| Classic | Laparoscopic | Total | Laparoscopic % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 1593 | 1631 | 3224 | 50.59% |

| Public | 38,091 | 5480 | 43,571 | 12.58% |

| Total | 39,684 | 7111 | 46,795 | 15.20% |

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | 17,965 | 9668 | 12,051 |

| Laparoscopic | 2757 | 1842 | 2512 |

| % Laparoscopic | 13.30% | 16% | 17.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garofil, N.D.; Bratucu, M.N.; Zurzu, M.; Paic, V.; Tigora, A.; Prunoiu, V.; Rogobete, A.; Balan, A.; Vladescu, C.; Strambu, V.D.E.; et al. Groin Hernia Repair during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Romanian Nationwide Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050970

Garofil ND, Bratucu MN, Zurzu M, Paic V, Tigora A, Prunoiu V, Rogobete A, Balan A, Vladescu C, Strambu VDE, et al. Groin Hernia Repair during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Romanian Nationwide Analysis. Medicina. 2023; 59(5):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050970

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarofil, Nicolae Dragos, Mircea Nicolae Bratucu, Mihai Zurzu, Vlad Paic, Anca Tigora, Virgiliu Prunoiu, Alexandru Rogobete, Ana Balan, Cristian Vladescu, Victor Dan Eugen Strambu, and et al. 2023. "Groin Hernia Repair during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Romanian Nationwide Analysis" Medicina 59, no. 5: 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050970

APA StyleGarofil, N. D., Bratucu, M. N., Zurzu, M., Paic, V., Tigora, A., Prunoiu, V., Rogobete, A., Balan, A., Vladescu, C., Strambu, V. D. E., & Radu, P. A. (2023). Groin Hernia Repair during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Romanian Nationwide Analysis. Medicina, 59(5), 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050970