Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Risk Factors among Saudi Females

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

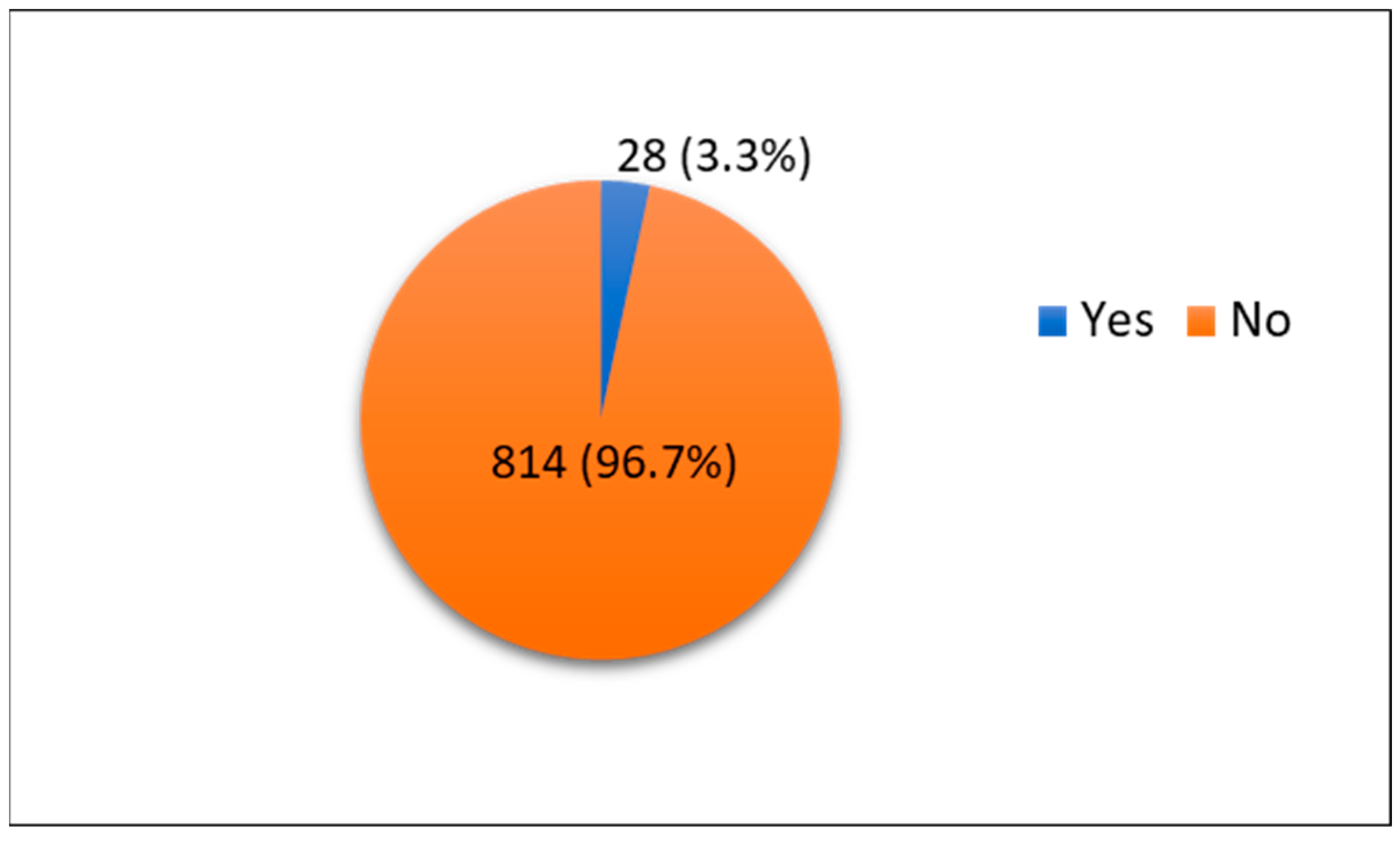

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haylen, B.T.; de Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, Y.; Brown, H.W.; Brubaker, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Daly, J.O.; Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luber, K.M. The definition, prevalence, and risk factors for stress urinary incontinence. Rev. Urol. 2004, 6 (Suppl. 3), S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; Wing, R.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Nyberg, L.M.; Kusek, J.W.; Orchard, T.J.; Ma, Y.; Vittinghoff, E.; Kanaya, A.M. Lifestyle intervention is associated with lower prevalence of urinary incontinence: The Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amselem, C.; Puigdollers, A.; Azpiroz, F.; Sala, C.; Videla, S.; Fernández-Fraga, X.; Whorwell, P.; Malagelada, J.R. Constipation: A potential cause of pelvic floor damage? Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010, 22, 150–153.e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.S.; Kennedy, C.M.; Turcea, A.M.; Rao, S.S.; Nygaard, I.E. Constipation in pregnancy: Prevalence, symptoms, and risk factors. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tähtinen, R.M.; Cartwright, R.; Tsui, J.F.; Aaltonen, R.L.; Aoki, Y.; Cárdenas, J.L.; El Dib, R.; Joronen, K.M.; Al Juaid, S.; Kalantan, S.; et al. Long-term Impact of Mode of Delivery on Stress Urinary Incontinence and Urgency Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.; O’Herlihy, C. The effects of labour and delivery on the pelvic floor. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2001, 15, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Xia, M.C.; Cui, F.; Chen, J.W.; Bian, X.D.; Xie, H.J.; Shuang, W.B. Epidemiological survey of adult female stress urinary incontinence. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, L.; Delpe, S.; Priest, T.; Reynolds, W.S. Physical Activity and Stress Incontinence in Women. Curr. Bladder Dysfunct. Rep. 2019, 14, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abufaraj, M.; Xu, T.; Cao, C.; Siyam, A.; Isleem, U.; Massad, A.; Soria, F.; Shariat, S.F.; Sutcliffe, S.; Yang, L. Prevalence and trends in urinary incontinence among women in the United States, 2005–2018. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 166.e1–166.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Badr, A.; Brasha, H.; Al-Raddadi, R.; Noorwali, F.; Ross, S. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among Saudi women. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2012, 117, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaweel, W.; Alharbi, M. Urinary incontinence: Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on health related quality of life in Saudi women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 31, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shaikh, G.; Al-Badr, A.; Al Maarik, A.; Cotterill, N.; Al-Mandeel, H.M. Reliability of Arabic ICIQ-UI short form in Saudi Arabia. Urol. Ann. 2013, 5, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, A.; Adefris, M.; Demeke, S. Urinary incontinence among pregnant women, following antenatal care at University of Gondar Hospital, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okunola, T.O.; Olubiyi, O.A.; Omoya, S.; Rosiji, B.; Ajenifuja, K.O. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in pregnancy in Ikere-Ekiti, Nigeria. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 2710–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, G.; Seven, M.; Guvenc, G.; Akyuz, A. Urinary Incontinence in Pregnant Women: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Its Effects on Health-Related Quality of Life. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2016, 43, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazy, W.; Rance, J.; Brown, A. Exploring maternal and health professional beliefs about the factors that affect whether women in Saudi Arabia attend antenatal care clinic appointments. Midwifery 2019, 76, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyhagen, M.; Åkervall, S.; Molin, M.; Milsom, I. The effect of childbirth on urinary incontinence: A matched cohort study in women aged 40–64 years. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 322.e1–322.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.; Ekström, A.; Gustafsson, C.; López, A.; Falconer, C.; Zetterström, J. Risk of urinary incontinence after childbirth: A 10-year prospective cohort study. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerdoğan, N.; Beji, N.K.; Yalçin, O. Urinary incontinence: Its prevalence, risk factors and effects on the quality of life of women living in a region of Turkey. Gynecol. Obstet. Investg. 2004, 58, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, B.; Ayub, S.H.; Mohd Zahid, A.Z.; Noorneza, A.R.; Isa, M.R.; Ng, P.Y. Urinary incontinence in primigravida: The neglected pregnancy predicament. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 198, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Seleme, M.; Cansi, P.F.; Consentino, R.F.; Kumakura, F.Y.; Moreira, G.A.; Berghmans, B. Urinary incontinence in pregnant women and its relation with socio-demographic variables and quality of life. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2013, 59, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eason, E.; Labrecque, M.; Marcoux, S.; Mondor, M. Effects of carrying a pregnancy and of method of delivery on urinary incontinence: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2004, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaji, S.E.; Shittu, O.S.; Bature, S.B.; Nasir, S.; Olatunji, O. Suffering in silence: Pregnant women’s experience of urinary incontinence in Zaria, Nigeria. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 150, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Itza, I.; Ibañez, L.; Arrue, M.; Paredes, J.; Murgiondo, A.; Sarasqueta, C. Influence of maternal weight on the new onset of stress urinary incontinence in pregnant women. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009, 20, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, K.P.; Herrmann, V.; Palma, P.C.; Riccetto, C.L.; Morais, S.S. Prevalence and correlates of stress urinary incontinence during pregnancy: A survey at UNICAMP Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006, 17, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narçiçeği, B.A.; Yakar, B.; Narçiçeği, H.R.; Önalan, E.; Pirinçci, E. Prevalence and associated factors of urinary incontinence among adult women in primary care. Cukurova Med. J. 2021, 46, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsawang, B. Risk factors for the development of stress urinary incontinence during pregnancy in primigravidae: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 178, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertunc, D.; Tok, E.C.; Pata, O.; Dilek, U.; Ozdemir, G.; Dilek, S. Is stress urinary incontinence a familial condition? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2004, 83, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenskaia, K.; Haidvogel, K.; Heidinger, C.; Doerfler, D.; Umek, W.; Hanzal, E. The greatest taboo: Urinary incontinence as a source of shame and embarrassment. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2011, 123, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | 20–29 | 480 | 57% |

| 30–39 | 190 | 22.6% | |

| 40–49 | 112 | 13.3% | |

| 50–59 | 53 | 6.3% | |

| 60 or more | 7 | 0.8% | |

| Residence | Northern | 86 | 10.2% |

| Southern | 92 | 10.9% | |

| Central | 281 | 33.4% | |

| Eastern | 124 | 14.7% | |

| Western | 259 | 30.8% | |

| Educational level | Primary | 3 | 0.4% |

| Intermediate | 5 | 0.6% | |

| Secondary | 153 | 18.2% | |

| Diploma | 64 | 7.6% | |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 617 | 73.3% | |

| Marital status | Single | 424 | 50.4% |

| Married | 373 | 44.3% | |

| Divorced | 39 | 4.6% | |

| Widowed | 6 | 0.7% | |

| Average monthly income (SAR) | Less than 4000 | 134 | 15.9% |

| 4000–8000 | 104 | 12.4% | |

| More than 8000 | 198 | 23.5% | |

| University incentive | 180 | 21.4% | |

| No monthly income | 226 | 26.8% | |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | Underweight (<18.5) | 58 | 6.9% |

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 364 | 43.2% | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 237 | 28.1% | |

| Obese (>30) | 183 | 21.7% | |

| Mean | SD 1 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 65.5 | 17.1 | |

| Height (cm) | 157 | 15.6 |

| Variable | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous conditions | Hypertension | 6 | 0.7% |

| Asthma | 3 | 0.4% | |

| Depression | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Uterine problems | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Arthritis | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Chronic constipation | 1 | 0.1% | |

| PCOS 1 | 4 | 0.5% | |

| Rheumatism | 2 | 0.2% | |

| Liver problems | 1 | 0.1% | |

| None | 827 | 98.2% | |

| Family history of SUI 2 | Yes | 62 | 7.4% |

| No | 544 | 64.6% | |

| I do not know | 236 | 28% | |

| Pregnancy | Yes | 352 | 41.8% |

| No | 490 | 58.2% | |

| Number of pregnancies (n = 352) | 1 | 61 | 17.3% |

| 2 | 65 | 18.5% | |

| 3 | 52 | 14.8% | |

| 4 | 72 | 20.5% | |

| 5 or more | 102 | 29% | |

| Number of vaginal deliveries (n = 352) | 0 | 71 | 20.2% |

| 1 | 67 | 19% | |

| 2 | 56 | 15.9% | |

| 3 | 44 | 12.5% | |

| 4 | 43 | 12.2% | |

| 5 or more | 71 | 20.2% | |

| Number of cesarean sections (n = 352) | 0 | 212 | 60.2% |

| 1 | 71 | 20.2% | |

| 2 | 31 | 8.8% | |

| 3 | 20 | 5.7% | |

| 4 | 10 | 2.8% | |

| 5 or more | 8 | 2.3% | |

| Smoking status | Yes | 35 | 4.2% |

| No | 807 | 95.8% | |

| Number of cigarettes per day (n = 35) | 10 or less | 31 | 88.6% |

| 11–20 | 4 | 11.4% | |

| 21–30 | 0 | 0% | |

| Chronic cough (n = 35) | Never | 18 | 51.4% |

| Sometimes | 12 | 34.3% | |

| Usually | 2 | 5.7% | |

| Always | 3 | 8.6% | |

| Frequency of urinary incontinence | Never happens | 621 | 73.8% |

| Once per week or less | 132 | 15.7% | |

| 2–3 times per week | 33 | 3.9% | |

| Once everyday | 29 | 3.4% | |

| Multiple times everyday | 22 | 2.6% | |

| All the time | 5 | 0.6% | |

| Amount of urine | Nothing | 617 | 73.3% |

| Small amount | 183 | 21.7% | |

| Average amount | 36 | 4.3% | |

| Large amount | 6 | 0.7% | |

| the presence of urinary incontinence | I don’t have urinary incontinence | 594 | 70.5% |

| Before reaching the toilet | 101 | 12% | |

| During sneezing, coughing, or laughing | 152 | 18.1% | |

| With active physical movements such as exercise or when lifting heavy objects | 43 | 5.1% | |

| After using the toilet and wearing clothes | 21 | 2.5% | |

| During sleep | 22 | 2.6% | |

| Without obvious reason | 31 | 3.7% | |

| At all times | 6 | 0.7% | |

| Other | 22 | 2.6% |

| Variable | Categories | Presence of Reported Diagnosis of SUI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | 20–29 | 4 (0.8%) | 0.001 * | |

| 30–39 | 9 (4.7%) | |||

| 40–49 | 7 (6.3%) | |||

| 50–59 | 8 (15.1%) | |||

| 60 or more | 0 (0%) | |||

| Residence | Northern | 2 (2.3%) | 0.090 | |

| Southern | 1 (1.1%) | |||

| Central | 8 (2.8%) | |||

| Eastern | 2 (1.6%) | |||

| Western | 15 (5.8%) | |||

| Educational level | Primary | 0 (0%) | 0.699 | |

| Intermediate | 0 (0%) | |||

| Secondary | 4 (2.6%) | |||

| Diploma | 1 (1.6%) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 23 (3.7%) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 2 (0.5%) | 0.001 * | |

| Married | 22 (5.9%) | |||

| Divorced | 3 (7.7%) | |||

| Widowed | 1 (16.7%) | |||

| Average monthly income (SAR) | Less than 4000 | 3 (2.2%) | <0.001 * | |

| 4000–8000 | 1 (1%) | |||

| More than 8000 | 19 (9.6%) | |||

| University incentive | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| No monthly income | 4 (1.8%) | |||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) | Underweight (<18.5) | 0 (0) | <0.001 * | |

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 6 (1.6%) | |||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 3 (1.3%) | |||

| Obese (>30) | 19 (10.4%) | |||

| Family history of SUI | Yes | 13 (21%) | <0.001 * | |

| No | 8 (1.5%) | |||

| I don’t know | 7 (3%) | |||

| History of Pregnancy | Yes | 25 (7.1%) | < 0.001* | |

| No | 3 (0.6%) | |||

| History of smoking | Yes | 2 (5.7%) | 0.625 | |

| No | 26 (3.2%) | |||

| Presence of reported diagnosis of SUI | ||||

| Yes | No | |||

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Weight (Kg) | 83 (18.1) | 65 (16.7) | <0.001 * | |

| Height (cm) | 160 (21.6) | 157 (15.4) | 0.420 | |

| Impact Score | Frequency (%) | Number of Cases Never Diagnosed with SUI 1 before |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 582 (69.1%) | 581 (99.8%) |

| 1 | 88 (10.5%) | 88 (100%) |

| 2 | 29 (3.4%) | 29 (100%) |

| 3 | 35 (4.2%) | 35 (100%) |

| 4 | 9 (1.1%) | 8 (88.9%) |

| 5 | 18 (2.1%) | 14 (77.8%) |

| 6 | 11 (1.3%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| 7 | 11 (1.3%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| 8 | 14 (1.7%) | 11 (78.6%) |

| 9 | 6 (0.7%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| 10 | 39 (4.6%) | 25 (64.1%) |

| ICIQ-SF 2 score | Frequency (%) | Number of cases never diagnosed with SUI before |

| Slight (0–5) | 689 (81.8%) | 687 (99.7%) |

| Moderate (6–12) | 112 (13.3%) | 102 (91.1%) |

| Severe (13–18) | 36 (4.3%) | 24 (66.7%) |

| Very severe (19–21) | 5 (0.6%) | 1 (20%) |

| Variable | ICIQ-SF Score | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slight | Moderate | Severe | Very Severe | ||

| N (%) | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–29 | 421 (61.1) | 49 (43.8) | 10 (27.8) | 0 (0) | <0.001 * |

| 30–39 | 156 (22.6) | 25 (22.3) | 8 (22.2) | 1 (20) | |

| 40–49 | 71 (10.3) | 28 (25) | 12 (33.3) | 1 (20) | |

| 50–59 | 36 (5.2) | 8 (7.1) | 6 (8.3) | 3 (60) | |

| 60 or more | 5 (0.7) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 49 (7.1) | 9 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 * |

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 319 (46.3) | 33 (29.5) | 11 (30.6) | 1 (20) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 194 (28.2) | 35 (31.3) | 7 (19.4) | 1 (20) | |

| Obese (>30) | 127 (18.4) | 35 (31.3) | 18 (50) | 3 (60) | |

| Presence of reported diagnosis of SUI | |||||

| Yes | 2 (0.3) | 10 (8.9) | 12 (33.3) | 4 (80) | <0.001 * |

| No | 687 (99.7) | 102 (91.1) | 24 (66.7) | 1 (20) | |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for Odds Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Lower–Upper) | |||

| Age group (years) | 0.582 | ||

| 20–29 | 1 | ||

| 30–39 | 1.71 | (0.34–8.60) | 0.515 |

| 40–49 | 1.27 | (0.19–8.64) | 0.808 |

| 50–59 | 4.33 | (0.52–36.32) | 0.177 |

| 60 or more | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.999 |

| Residence | 0.241 | ||

| Northern | 1 | ||

| Southern | 1.26 | (0.05–31.69) | 0.888 |

| Central | 3.97 | (0.46–34.32) | 0.211 |

| Eastern | 1.76 | (0.13–23.82) | 0.671 |

| Western | 6.70 | (0.85–52.62) | 0.070 |

| Marital status | 0.818 | ||

| Single | 1 | ||

| Married | 2.49 | (0.19–32.34) | 0.485 |

| Divorced | 3.02 | (0.19–48.51) | 0.435 |

| Widowed | 7.15 | (0.09–574.91) | 0.380 |

| Educational level | 0.925 | ||

| Primary | 1 | ||

| Intermediate | 1.11 | (0.00) | 1.000 |

| Secondary | 3.38 | (0.00) | 0.999 |

| Diploma | 8.21 | (0.00) | 0.999 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 1.93 | (0.00) | 0.999 |

| Average monthly income (SAR) | 0.164 | ||

| Less than 4000 | 1 | ||

| 4000–8000 | 0.40 | (0.03–5.01) | 0.474 |

| More than 8000 | 4.03 | (0.73–22.38) | 0.111 |

| University incentive | 0.72 | (0.05–11.15) | 0.811 |

| No monthly income | 1.12 | (0.18–7.17) | 0.904 |

| Family history of SUI | 0.000 | ||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 19.68 | (5.46–70.97) | 0.000 * |

| I don’t know | 4.35 | (1.19–15.85) | 0.026 * |

| Presence of history of pregnancy | 2.58 | (0.01–732.51) | 0.742 |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.704 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 0.49 | (0.01–41.00) | 0.755 |

| 3 | 0.14 | (0.00–5.60) | 0.296 |

| 4 | 0.35 | (0.03–4.82) | 0.434 |

| 5 or more | 0.34 | (0.04–3.17) | 0.344 |

| Number of vaginal deliveries | 0.217 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 4.59 | (0.42–50.11) | 0.212 |

| 2 | 3.63 | (0.17–79.14) | 0.413 |

| 3 | 5.96 | (0.13–280.47) | 0.364 |

| 4 | 0.62 | (0.01–70.00) | 0.845 |

| 5 or more | 0.47 | (0.00–101.46) | 0.784 |

| Number of caesarian sections | 0.977 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.12 | (0.20–6.35) | 0.903 |

| 2 | 2.32 | (0.18–29.38) | 0.517 |

| 3 | 1.60 | (0.04–63.16) | 0.802 |

| 4 | 4.94 | (0.05–477.39) | 0.494 |

| 5 or more | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.999 |

| Smoking status | 9.00 | (0.99–82.29) | 0.052 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gari, A.M.; Alamer, E.H.A.; Almalayo, R.O.; Alshaddadi, W.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Aloufi, R.S.; Baradwan, S. Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Risk Factors among Saudi Females. Medicina 2023, 59, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050940

Gari AM, Alamer EHA, Almalayo RO, Alshaddadi WA, Alamri SA, Aloufi RS, Baradwan S. Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Risk Factors among Saudi Females. Medicina. 2023; 59(5):940. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050940

Chicago/Turabian StyleGari, Abdulrahim M., Ethar H. Alhashmi Alamer, Rania O. Almalayo, Wafa A. Alshaddadi, Sadin A. Alamri, Razan S. Aloufi, and Saeed Baradwan. 2023. "Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Risk Factors among Saudi Females" Medicina 59, no. 5: 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050940

APA StyleGari, A. M., Alamer, E. H. A., Almalayo, R. O., Alshaddadi, W. A., Alamri, S. A., Aloufi, R. S., & Baradwan, S. (2023). Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence and Risk Factors among Saudi Females. Medicina, 59(5), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050940