Performance of Six Clinical Physiological Scoring Systems in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Very Elderly Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Emergency Department

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Study Outcomes and Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

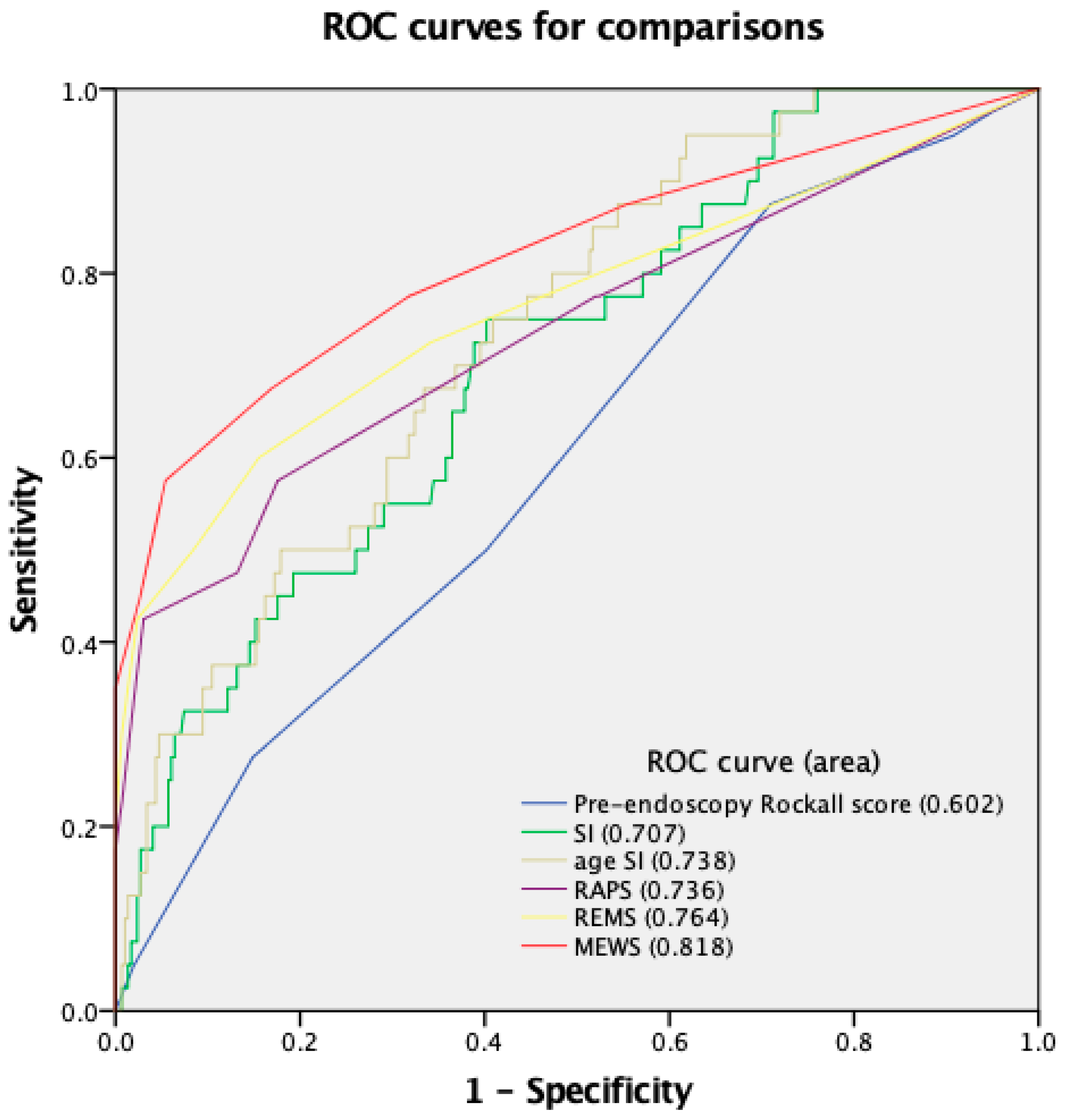

3.2. Performance of Clinical Scoring Systems

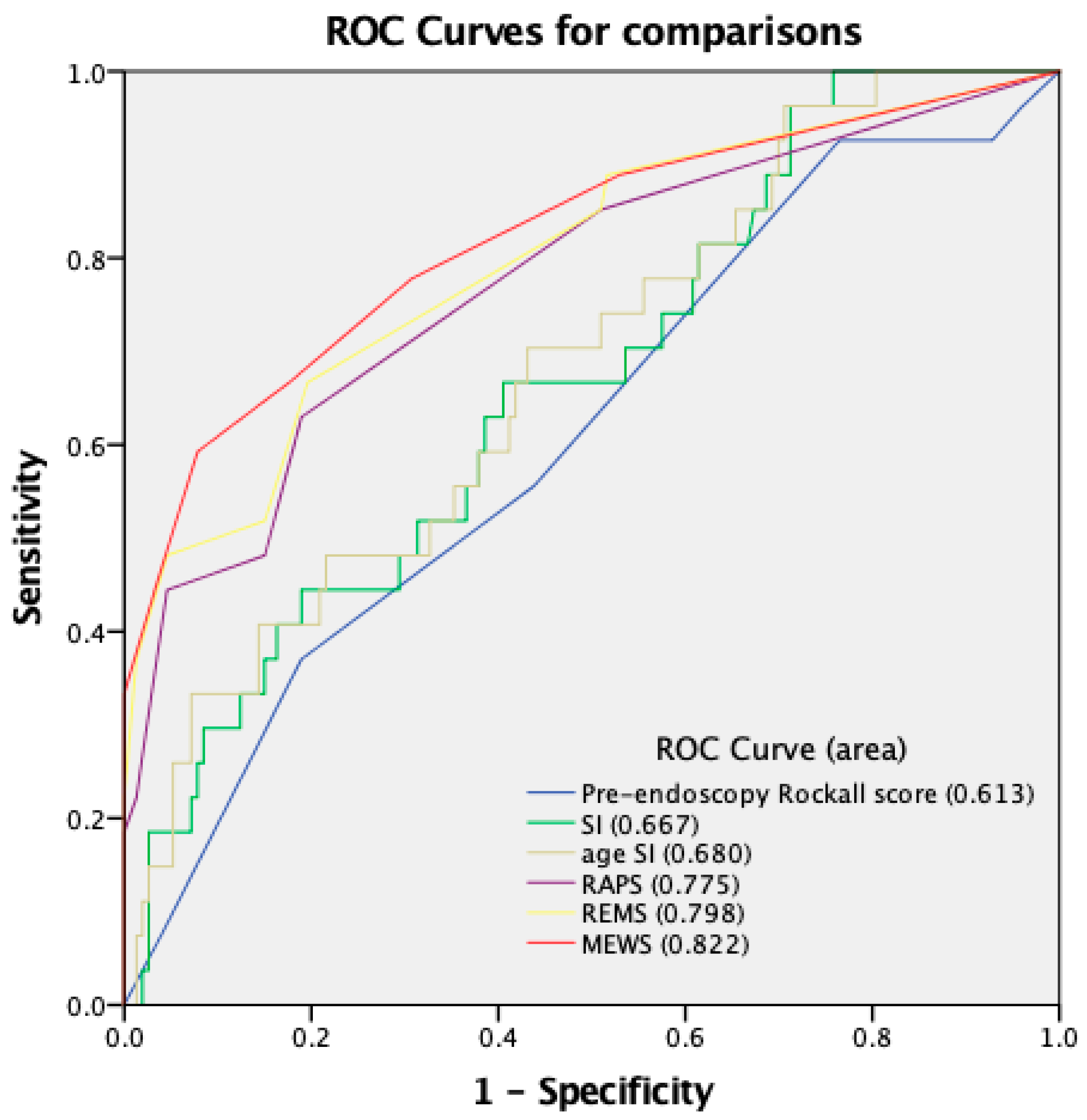

3.3. Subgroup Analysis for Very Elderly Patients

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rockall, T.A.; Logan, R.F.; Devlin, H.B.; Northfield, T.C. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. Bmj 1995, 311, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearnshaw, S.A.; Logan, R.F.; Lowe, D.; Travis, S.P.; Murphy, M.F.; Palmer, K.R. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: Patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut 2011, 60, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peery, A.F.; Crockett, S.D.; Murphy, C.C.; Jensen, E.T.; Kim, H.P.; Egberg, M.D.; Lund, J.L.; Moon, A.M.; Pate, V.; Barnes, E.L.; et al. Burden and Cost of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States: Update 2021. Gastroenterology. 2022, 162, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, A.J.; Laine, L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Bmj 2019, 364, l536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, K.U.; Kim, S.J.; Seo, S.I.; Kim, H.S.; Jang, M.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Shin, W.G. Predictors for the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with presumed acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Walline, J.H.; Yu, X.; Zhu, H. Fresh Frozen Plasma in Cases of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Does Not Improve Outcomes. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 934024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuerth, B.A.; Rockey, D.C. Changing Epidemiology of Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage in the Last Decade: A Nationwide Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, G.J.; Arvaniti, V.; Assimakopoulos, S.F.; Thomopoulos, K.C.; Xourgias, V.; Mylonakou, I.; Nikolopoulou, V.N. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in octogenarians: Clinical outcome and factors related to mortality. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 4047–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Pausawasdi, N.; Laosanguaneak, N.; Bubthamala, J.; Tanwandee, T.; Leelakusolvong, S. Characteristics and outcomes of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy in the elderly. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3724–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Sep/un_pop_2020_pf_ageing_10_key_messages.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Ukkonen, M.; Jämsen, E.; Zeitlin, R.; Pauniaho, S.L. Emergency department visits in older patients: A population-based survey. BMC Emerg. Med. 2019, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapsang, A.G.; Shyam, D.C. Scoring systems of severity in patients with multiple trauma. Cir. Esp. 2015, 93, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Chang, A.M.; Matsuura, A.C.; Marcoon, S.; Hollander, J.E. Comparison of cardiac risk scores in ED patients with potential acute coronary syndrome. Crit. Pathw. Cardiol. 2011, 10, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.C.; Lyden, P.D. The modified National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale: Its time has come. Int. J. Stroke 2009, 4, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkun, A.N.; Almadi, M.; Kuipers, E.J.; Laine, L.; Sung, J.; Tse, F.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Abraham, N.S.; Calvet, X.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Management of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Guideline Recommendations From the International Consensus Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Song, Y.W.; Tak, D.H.; Ahn, B.M.; Kang, S.H.; Moon, H.S.; Sung, J.K.; Jeong, H.Y. The AIMS65 Score Is a Useful Predictor of Mortality in Patients with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Urgent Endoscopy in Patients with High AIMS65 Scores. Clin Endosc. 2015, 48, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, S.; Köse, A.; Arslan, E.D.; Erdoğan, S.; Üçbilek, E.; Çevik, İ.; Ayrık, C.; Sezgin, O. Validity of modified early warning, Glasgow Blatchford, and pre-endoscopic Rockall scores in predicting prognosis of patients presenting to emergency department with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2015, 23, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaoğlu, S.; Çetinkaya, H.B. Use of age shock index in determining severity of illness in patients presenting to the emergency department with gastrointestinal bleeding. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 47, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzaur, B.L.; Croce, M.A.; Fischer, P.E.; Magnotti, L.J.; Fabian, T.C. New vitals after injury: Shock index for the young and age x shock index for the old. J. Surg. Res. 2008, 147, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgöwer, M.; Burri, C. ["Shock index"]. Dtsch. Med Wochenschr. 1967, 92, 1947–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockall, T.A.; Logan, R.F.; Devlin, H.B.; Northfield, T.C. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 1996, 38, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.J.; Fisher, C.J., Jr.; Willitis, N.H. The Rapid Acute Physiology Score. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1987, 5, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, T.; Terent, A.; Lind, L. Rapid Emergency Medicine score: A new prognostic tool for in-hospital mortality in nonsurgical emergency department patients. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 255, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbe, C.P.; Kruger, M.; Rutherford, P.; Gemmel, L. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. Qjm 2001, 94, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raccah, D.; Miossec, P.; Esposito, V.; Niemoeller, E.; Cho, M.; Gerich, J. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide in elderly (≥65 years old) and very elderly (≥75 years old) patients with type 2 diabetes: An analysis from the GetGoal phase III programme. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2015, 31, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, N.; Kim, K.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, T.; Shin, S.M. Delayed endoscopy is associated with increased mortality in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.L.; Wong, S.H.; Lau, L.H.; Lui, R.N.; Mak, J.W.; Tang, R.S.; Yip, T.C.; Wu, W.K.; Wong, G.L.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Timing of endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A territory-wide cohort study. Gut 2022, 71, 1544–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Stanley, A.J.; Morris, A.J.; Camus, M.; Lau, J.; Lanas, A.; Laursen, S.B.; Radaelli, F.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Gonçalves, T.C.; et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2021. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 300–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, X.; Tang, Z.; You, T. Scoring systems used to predict mortality in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.; Gonçalves, T.C.; Magalhães, J.; Cotter, J. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk scores: Who, when and why? World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2016, 7, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodpoor, A.; Sanaie, S.; Saghaleini, S.H.; Ostadi, Z.; Hosseini, M.S.; Sheshgelani, N.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Samim, A.; Rahimi-Bashar, F. Prognostic value of National Early Warning Score and Modified Early Warning Score on intensive care unit readmission and mortality: A prospective observational study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 938005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, P.; Mao, Y. Performance of Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) and Circulation, Respiration, Abdomen, Motor, and Speech (CRAMS) score in trauma severity and in-hospital mortality prediction in multiple trauma patients: A comparison study. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.J.; Graves, K.K.; Kukhareva, P.V.; Johnson, S.A.; Cedillo, M.; Sanford, M.; Dunson, W.A., Jr.; White, M.; Roach, D.; Arego, J.J.; et al. Modified early warning score-based clinical decision support: Cost impact and clinical outcomes in sepsis. JAMIA Open 2020, 3, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, T.; Hasegawa, I.; Uzura, M.; Okuno, K.; Otani, K.; Ohtaki, Y.; Sekine, A.; Takeda, S. Comparison of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) and the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) for predicting admission and in-hospital mortality in elderly patients in the pre-hospital setting and in the emergency department. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundar, Z.D.; Ergin, M.; Karamercan, M.A.; Ayranci, K.; Colak, T.; Tuncar, A.; Cander, B.; Gul, M. Modified Early Warning Score and VitalPac Early Warning Score in geriatric patients admitted to emergency department. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Liu, E.; Xiao, C.; Yu, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, L. The utility of MEWS for predicting the mortality in the elderly adults with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study with comparison to other predictive clinical scores. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, W.; Pan, T.; Deng, J.; Xu, J. Comparison of Different Scoring Systems for Prediction of Mortality and ICU Admission in Elderly CAP Population. Clin. Interv. Aging 2021, 16, 1917–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffernan, D.S.; Thakkar, R.K.; Monaghan, S.F.; Ravindran, R.; Adams, C.A., Jr.; Kozloff, M.S.; Gregg, S.C.; Connolly, M.D.; Machan, J.T.; Cioffi, W.G. Normal presenting vital signs are unreliable in geriatric blunt trauma victims. J. Trauma 2010, 69, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolow, E.; Moreau, C.; Sayana, H.; Patel, S. Management of Non-Variceal Upper GI Bleeding in the Geriatric Population: An Update. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2021, 23, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Wilber, S.T. Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 101–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

| Age (years) | <60 | 60–70 | ≥80 | |

| Shock | ||||

| HR (/min) | <100 | >100 | >100 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | >100 | >100 | <100 | |

| Comorbidity | None | IHD, CHF, any major comorbidity | Renal/liver failure, metastatic malignancy | |

| Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 |

| HR (/min) | 70–109 | 55–69 110–139 | 40–54 140–179 | ≤39 ≥180 | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 70–109 | 55–69 110–139 | 130–159 | ≤49 ≥160 | |

| RR (/min) | 12–24 | 10–11 25–34 | 6–9 | 35–49 | ≤5 ≥50 |

| GCS | ≥14 | 11–13 | 8–10 | 5–7 | ≤4 |

| Score | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | +5 | +6 |

| Age (years) | <45 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | ≥74 | ||

| HR (/min) | 70–109 | 55–69 110–139 | 40–54 140–179 | ≤39 >179 | |||

| MAP (mmHg) | 70–109 | 55–69 110–129 | 130–159 | ≤49 >159 | |||

| RR (/min) | 12–24 | 10–11 25–34 | 6–9 | 35–49 | ≤5 >49 | ||

| GCS | ≥14 | 11–13 | 8–10 | 5–7 | 3 or 4 | ||

| SpO2(%) | >89 | 86–89 | 75–85 | <75 | |||

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 101–119 | 81–100 | 71–80 ≥200 | <70 |

| HR (/min) | 51–100 | 41–50 101–110 | <40 111–129 | ≥130 |

| RR (/min) | 9–14 | 15–20 | <9 21–29 | ≥30 |

| BT (°C) | 35–38.4 | <35 ≥38.5 | ||

| AVPU score | Alert | Reacts to Voice | Reacts to Pain | Unresponsive |

| Variable | Mortality Group (n = 40) | Non-Mortality Group (n = 296) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age b | 78 (73–85) | 75 (68–79) | <0.01 * |

| Sex, M/F | 27/13 (2.08:1) | 205/91 (2.25:1) | 0.82 |

| Vital signs | |||

| BT (°C) b | 36.0 (35.6–37.0) | 36.2 (35.8–36.7) | 0.61 |

| Heart rate (/min) a | 100.70 ± 20.49 | 93.45 ± 18.31 | 0.02 * |

| SBP (mmHg) a | 101.70 ± 34.32 | 121.17 ± 32.43 | <0.01 * |

| DBP (mmHg) b | 63 (50–77) | 69 (58–83) | 0.08 |

| MAP (mmHg) b | 75 (57–93) | 85 (72–103) | <0.01 * |

| Respiratory rate (/min) a | 22.58 ± 5.43 | 19.10 ± 1.60 | <0.01 * |

| GCS b | 12 (7–15) | 15 (14–15) | <0.01 * |

| Symptom, n (%) | |||

| Hematemesis | 10 (25.0) | 46 (15.5) | 0.13 |

| Coffee-ground vomiting | 14 (35.0) | 36 (12.2) | <0.01 * |

| Melena | 16 (40) | 189 (63.9) | <0.01 * |

| Others | 0 (0) | 33 (11.1) | 0.03 * |

| Lab test results | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) a | 8.55 ± 2.68 | 9.30 ± 2.74 | 0.10 |

| Platelets (×103/μL) b | 155 (93–297) | 188 (126–248) | 0.95 |

| WBC (×103/μL) b | 11.9 (6.6–18.4) | 8.5 (6.2–11.6) | <0.01 * |

| Band (%) b | 0.25 (0–4.2) | 0 (0–0) | <0.01 * |

| Albumin a | 2.85 ± 0.63 | 3.49 ± 0.59 | <0.01 * |

| Bilirubin b | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.33 |

| BUN b | 42.2 (27.4–67.2) | 36.7 (21.4–56.1) | 0.21 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) b | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 0.97 |

| INR b | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.05 * |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 25 (62.5) | 169 (57.1) | 0.52 |

| DM | 15 (37.5) | 105 (35.5) | 0.80 |

| CVD | 10 (25) | 39 (13.3) | 0.05 * |

| CVA | 6 (15) | 6 (2) | <0.01* |

| CKD | 4 (10) | 31 (10.5) | 0.93 |

| COPD | 3 (7.5) | 5 (1.7) | 0.02 * |

| Cirrhosis | 12 (30) | 50 (16.9) | 0.05 * |

| Malignancy | 17 (42.5) | 36 (12.2) | <0.01 * |

| Scoring System | Mortality Group (n = 40) | Non-Mortality Group (n = 296) | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p Value | OR (95%CI) | p Value | |||

| Pre-endoscopy Rockall | 4.62 ± 1.27 | 4.14 ± 1.32 | 1.34 (1.03–1.76) | 0.03 * | 1.24 (0.72–2.14) | 0.44 |

| SI | 1.08 ± 0.36 | 0.84 ± 0.31 | 6.83 (2.75–16.94) | <0.01 * | 2.18 (0.39–12.37) | 0.38 |

| Age SI | 85.33 ± 30.49 | 62.41 ± 24.59 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.01 * | 1.02 (0.98–11.81) | 0.17 |

| RAPS | 2.65 ± 2.88 | 1.39 ± 1.52 | 1.72 (1.44–2.06) | <0.01 * | 1.61 (1.14–2.28) | <0.01 * |

| REMS | 9.90 ± 3.49 | 6.91 ± 1.61 | 1.74 (1.46–2.06) | <0.01 * | 1.72 (1.20–2.47) | <0.01 * |

| MEWS | 5.00 ± 2.61 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 2.16 (1.75–2.66) | <0.01 * | 2.14 (1.39–3.31) | <0.01 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, P.-H.; Hung, S.-K.; Ko, C.-A.; Chang, C.-P.; Hsiao, C.-T.; Chung, J.-Y.; Kou, H.-W.; Chen, W.-H.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Ku, K.-H.; et al. Performance of Six Clinical Physiological Scoring Systems in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Very Elderly Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Emergency Department. Medicina 2023, 59, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030556

Wu P-H, Hung S-K, Ko C-A, Chang C-P, Hsiao C-T, Chung J-Y, Kou H-W, Chen W-H, Hsieh C-H, Ku K-H, et al. Performance of Six Clinical Physiological Scoring Systems in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Very Elderly Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Emergency Department. Medicina. 2023; 59(3):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030556

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Po-Han, Shang-Kai Hung, Chien-An Ko, Chia-Peng Chang, Cheng-Ting Hsiao, Jui-Yuan Chung, Hao-Wei Kou, Wan-Hsuan Chen, Chiao-Hsuan Hsieh, Kai-Hsiang Ku, and et al. 2023. "Performance of Six Clinical Physiological Scoring Systems in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Very Elderly Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Emergency Department" Medicina 59, no. 3: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030556

APA StyleWu, P.-H., Hung, S.-K., Ko, C.-A., Chang, C.-P., Hsiao, C.-T., Chung, J.-Y., Kou, H.-W., Chen, W.-H., Hsieh, C.-H., Ku, K.-H., & Wu, K.-H. (2023). Performance of Six Clinical Physiological Scoring Systems in Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in Elderly and Very Elderly Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Emergency Department. Medicina, 59(3), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030556