Oral Health and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants Selection

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Oral Examination

2.4. Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Oral Findings

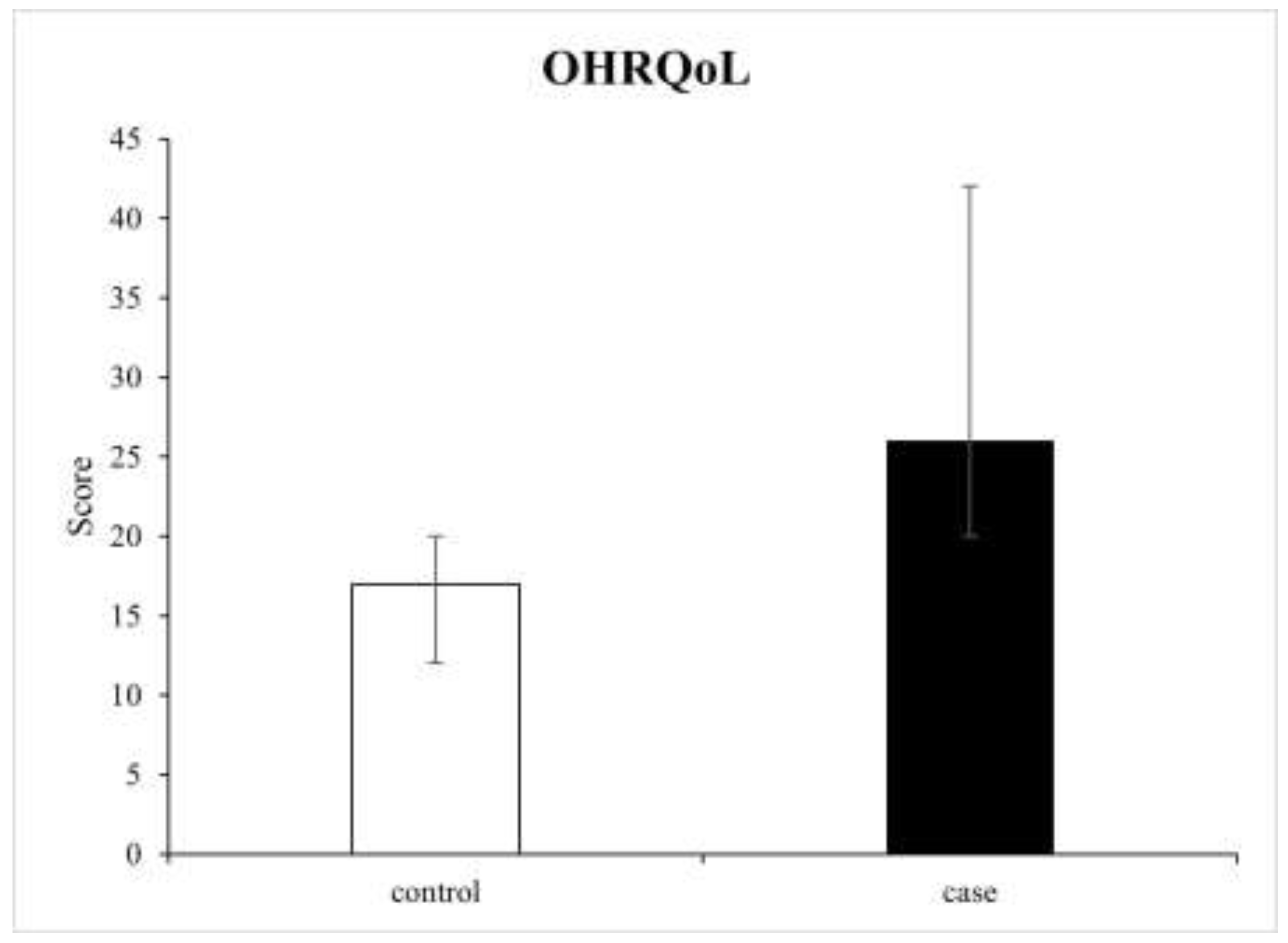

3.3. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

3.4. Factors Associated with OHRQoL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowman, S.J. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Lupus 2018, 27, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.; La Barbera, L.; Lo Pizzo, M.; Ciccia, F.; Sireci, G.; Guggino, G. Invariant NKT Cells and Rheumatic Disease: Focus on Primary Sjogren Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariette, X.; Criswell, L.A. Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retamozo, S.; Acar-Denizli, N.; Rasmussen, A.; Horváth, I.F.; Baldini, C.; Priori, R.; Sandhya, P.; Hernandez-Molina, G.; Armagan, B.; Praprotnik, S.; et al. Systemic manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome out of the ESSDAI classification: Prevalence and clinical relevance in a large international, multi-ethnic cohort of patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 118, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C.M.; Berg, K.M.; Cha, S.; Reeves, W.H. Salivary dysfunction and quality of life in Sjögren syndrome: A critical oral-systemic connection. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Lopez-Pintor, R.M.; Gonzalez-Serrano, J.; Fernandez-Castro, M.; Casanas, E.; Hernandez, G. Oral lesions in Sjogren’s syndrome: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2018, 23, e391–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, N.; Katada, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nishioka, A.; Sekiguchi, M.; Kitano, M.; Kitano, S.; Sano, H.; Matsui, K. Evaluation of changes in oral health-related quality of life over time in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Mod. Rheumatol. 2021, 31, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šijan Gobeljić, M.; Milić, V.; Pejnović, N.; Damjanov, N. Chemosensory dysfunction, Oral disorders and Oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, W.; Leung, K.C.M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Mok, M.Y.; Leung, M.H. Sicca Symptoms, Oral Health Conditions, Salivary Flow and Oral Candida in Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enger, T.B.; Palm, Ø.; Garen, T.; Sandvik, L.; Jensen, J.L. Oral distress in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: Implications for health-related quality of life. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, A.S.; Leung, K.C.; Leung, W.K.; Wong, M.C.; Lau, C.S.; Mok, T.M. Impact of Sjögren’s syndrome on oral health-related quality of life in southern Chinese. J. Oral Rehabil. 2004, 31, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; Rasmussen, A.; Scofield, H.; Vitali, C.; Bowman, S.J.; et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren’s syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, R.; Brokstad, K.A.; Jonsson, M.V.; Delaleu, N.; Skarstein, K. Current concepts on Sjögren’s syndrome—Classification criteria and biomarkers. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 126, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Castro, M.; López-Pintor, R.M.; Serrano, J.; Ramírez, L.; Sanz, M.; Andreu, J.L.; Muñoz Fernández, S. Grupo EPOX-SSp. Protocolised odontological assessment of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Reumatol. Clin. 2021, 17, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekić, M.; Daković, D.; Kovačević, V.; Čutović, T.; Ilić, I.; Ilić, M. Testing of the Serbian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) questionnaire among professional members of the Serbian Armed Forces. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2021, 78, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanemberg, J.C.; Cardoso, J.A.; Slob, E.M.G.B.; López-López, J. Quality of life related to oral health and its impact in adults. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, H.; Ovitt, C.E. Novel impacts of saliva with regard to oral health. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthen, S.; Young, A.; Herlofson, B.B.; Aqrawi, L.A.; Rykke, M.; Hove, L.H.; Palm, Ø.; Jensen, J.L.; Singh, P.B. Oral disorders, saliva secretion, and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 125, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błochowiak, K.; Olewicz-Gawlik, A.; Polańska, A.; Nowak-Gabryel, M.; Kocięcki, J.; Witmanowski, H.; Sokalski, J. Oral mucosal manifestations in primary and secondary Sjögren syndrome and dry mouth syndrome. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2016, 33, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.C.; McMillan, A.S.; Leung, W.K.; Wong, M.C.; Lau, C.S.; Mok, T.M. Oral health condition and saliva flow in southern Chinese with Sjögren’s syndrome. Int. Dent. J. 2004, 54, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmalz, G.; Patschan, S.; Patschan, D.; Ziebolz, D. Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Rheumatic Diseases-A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Alcayaga, G.; Herrera, A.; Espinoza, I.; Rios-Erazo, M.; Aguilar, J.; Leiva, L.; Shakhtur, N.; Wurmann, P.; Geenen, R. Illness Experience and Quality of Life in Sjögren Syndrome Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.J.; Hsu, C.W.; Lu, M.C.; Koo, M. Increased risk of developing dental diseases in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome-A secondary cohort analysis of population-based claims data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Narváez, R.V.; Valenzuela-Narváez, D.R.; Valenzuela-Narváez, D.A.O.; Córdova-Noel, M.E.; Mejía-Ruiz, C.L.; Salcedo-Rodríguez, M.N.; Gonzales-Aedo, O. Periodontal disease as a predictor of chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage in older adults. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211033266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujović, S.; Desnica, J.; Mijailović, S.; Milovanović, D. Translation, transcultural adaptation, and validation of the Serbian version of the PSS-QoL questionnaire—A pilot research. Vojn. Pregl. 2022, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, A.; Stradner, M.H.; Hermann, J.; Unger, J.; Stamm, T.; Graninger, W.B.; Dejaco, C. Assessing health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome-The PSS-QoL. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 48, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Case Group (N = 40) | Control Group (N = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] Males Females | ||

| 2 (5.0) 38 (95.0) | 1 (2.5) 39 (97.5) | |

| Education [n (%)] Elementary school High school University degree Doctoral degree | ||

| 9 (22.5) 18 (45.0) 11 (27.5) 2 (5.0) | 9 (22.5) 20 (50.0) 10 (25.0) 1 (2.5) | |

| Employment [n (%)] Employed Unemployed Retired | ||

| 4 (10.0) 12 (30.0) 24 (60.0) | 3 (7.5) 15 (37.5) 22 (55.0) | |

| Marital status [n (%)] Single In a relationship/married Divorced Widowed | ||

| 1 (2.5) 29 (72.5) 3 (7.5) 7 (17.5) | 3 (7.5) 26 (65.0) 2 (5.0) 9 (22.5) | |

| Alcohol [n (%)] Never Sometimes Regularly | ||

| 36 (90.0) 4 (10.0) 0 (0.0) | 39 (97.5) 1 (2.5) 0 (0.0) | |

| Physical activity [n (%)] Never Sometimes Regularly | ||

| 30 (75.0) 8 (20.0) 2 (5.0) | 29 (72.5) 7 (17.5) 4 (10.0) | |

| Disease duration [median (IQR)] | 10 (13.0) | 7 (8.0) |

| Variables | Case Group (N = 40) | Control Group (N = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| pSS systemic manifestations [n (%)] | ||

| Skin involvement | 6 (15.0) | 1 (2.5) |

| Musculoskeletal involvement | 37 (92.5) | 24 (60.0) |

| Renal involvement | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Lung involvement | 4 (10.0) | 2 (5.0) |

| PNS involvement | 9 (22.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Hematological involvement | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Endocrine involvement | 3 (7.5) | 8 (20.0) |

| Immunological involvement | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| pSS serological findings [n (%)] | ||

| RF+ | 29 (72.5) | 25 (62.5) |

| ANA+ | 36 (90.0) | 31 (77.5) |

| pSS medication [n (%)] | ||

| Chloroquine | 29 (72.5) | 16 (40.0) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (2.5) | 18 (45.0) |

| Antimalarials + corticosteroids | 10 (25.0) | 6 (15.0) |

| Oral Lesions and Symptoms | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Exfoliative cheilitis | 29 (36.3) | 51 (63.7) |

| Angular cheilitis | 6 (7.5) | 74 (92.5) |

| Aphthae | 13 (16.3) | 67 (83.7) |

| Traumatic lesions | 8 (10.0) | 72 (90.0) |

| Periodontal disease | 24 (30.0) | 56 (70.0) |

| Dental caries | 16 (20.0) | 64 (80.0) |

| Geographic tongue | 3 (3.8) | 77 (96.2) |

| Coated tongue | 8 (10.0) | 72 (90.0) |

| Atrophic glossitis | 10 (12.5) | 70 (87.5) |

| Denture stomatitis | 9 (11.3) | 71 (88.7) |

| Erythematous candidiasis | 3 (3.8) | 77 (96.2) |

| Lichen planus | 4 (5.0) | 76 (95.0) |

| Generalized stomatitis | 5 (6.3) | 75 (93.7) |

| Chewing difficulties | 24 (30.0) | 56 (70.0) |

| Swallowing difficulties | 24 (30.0) | 56 (70.0) |

| Speaking difficulties | 10 (12.5) | 70 (87.5) |

| Denture-wearing difficulties | 15 (18.8) | 65 (81.2) |

| Burning sensation | 26 (32.5) | 54 (67.5) |

| Taste alteration | 20 (25.0) | 60 (75.0) |

| Periodontal Indexes a | Case Group Median (IQR) | Control Group Median (IQR) | All Patients Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPITN * | 2.67 (0.67) | 1.50 (0.83) | 2.17 (1.30) |

| PI * | 1.96 (0.56) | 0.66 (0.38) | 1.29 (1.30) |

| GI * | 1.77 (0.59) | 0.83 (0.21) | 1.37 (0.96) |

| SBI * | 2.02 (0.74) | 0.41 (0.15) | 0.56 (1.64) |

| OHIP-14 Domains a | Case Group Median (IQR) | Control Group Median (IQR) | All Patients Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional limitation * | 4.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.0) | 3.0 (2.0) |

| Physical pain * | 6.0 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.0) | 6.0 (1.0) |

| Psychological discomfort * | 6.0 (1.0) | 4.0 (0.0) | 5.0 (2.0) |

| Physical disability * | 2.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| Psychological disability * | 5.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.0) | 4.0 (2.0) |

| Social disability * | 3.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| Handicap * | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Oral Manifestations a | OHIP-14 Score Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Exfoliative cheilitis ** Yes No | 26.0 (5.0) 18.0 (5.0) |

| Angular cheilitis * Yes No | 26.0 (8.0) 20.0 (9.0) |

| Aphthae ** Yes No | 27.0 (4.0) 19.0 (8.0) |

| Traumatic lesions * Yes No | 26.0 (6.0) 19.5 (9.0) |

| Periodontal disease ** Yes No | 26.0 (4.0) 18.0 (8.0) |

| Caries * Yes No | 25.5 (3.0) 19.0 (9.0) |

| Coated tongue * Yes No | 26.5 (5.0) 19.5 (9.0) |

| Atrophic glossitis ** Yes No | 30.0 (5.0) 19.0 (9.0) |

| Denture stomatitis * Yes No | 27.0 (5.0) 19.0 (9.0) |

| Generalized stomatitis * Yes No | 29.0 (12.0) 20.0 (9.0) |

| Chewing difficulties ** Yes No | 27.0 (5.0) 18.0 (8.0) |

| Swallowing difficulties ** Yes No | 26.5 (5.0) 18.0 (7.0) |

| Speaking difficulties * Yes No | 28.0 (6.0) 19.0 (9.0) |

| Denture-wearing difficulties ** Yes No | 27.0 (6.0) 19.0 (9.0) |

| Burning sensation ** Yes No | 26.5 (5.0) 18.0 (7.0) |

| Taste alteration ** Yes No | 26.0 (5.0) 17.0 (4.0) |

| Variable a | CPITN * | PI * | GI * | SBI * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-14 | 0.600 | 0.763 | 0.720 | 0.681 |

| Variables a | B | β | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group allocation * | 9.112 | 0.731 | 6.924–11.301 |

| Systemic involvement | 1.236 | 0.066 | −1.311–3.782 |

| Medication | 0.008 | 0.001 | −0.971–0.987 |

| CPITN | 1.195 | 0.144 | −0.176–2.566 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vujovic, S.; Desnica, J.; Stevanovic, M.; Mijailovic, S.; Vojinovic, R.; Selakovic, D.; Jovicic, N.; Rosic, G.; Milovanovic, D. Oral Health and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Medicina 2023, 59, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030473

Vujovic S, Desnica J, Stevanovic M, Mijailovic S, Vojinovic R, Selakovic D, Jovicic N, Rosic G, Milovanovic D. Oral Health and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Medicina. 2023; 59(3):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030473

Chicago/Turabian StyleVujovic, Sanja, Jana Desnica, Momir Stevanovic, Sara Mijailovic, Radisa Vojinovic, Dragica Selakovic, Nemanja Jovicic, Gvozden Rosic, and Dragan Milovanovic. 2023. "Oral Health and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome" Medicina 59, no. 3: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030473

APA StyleVujovic, S., Desnica, J., Stevanovic, M., Mijailovic, S., Vojinovic, R., Selakovic, D., Jovicic, N., Rosic, G., & Milovanovic, D. (2023). Oral Health and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Medicina, 59(3), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59030473