Menstruation among In-School Adolescent Girls and Its Literacy and Practices in Nigeria: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

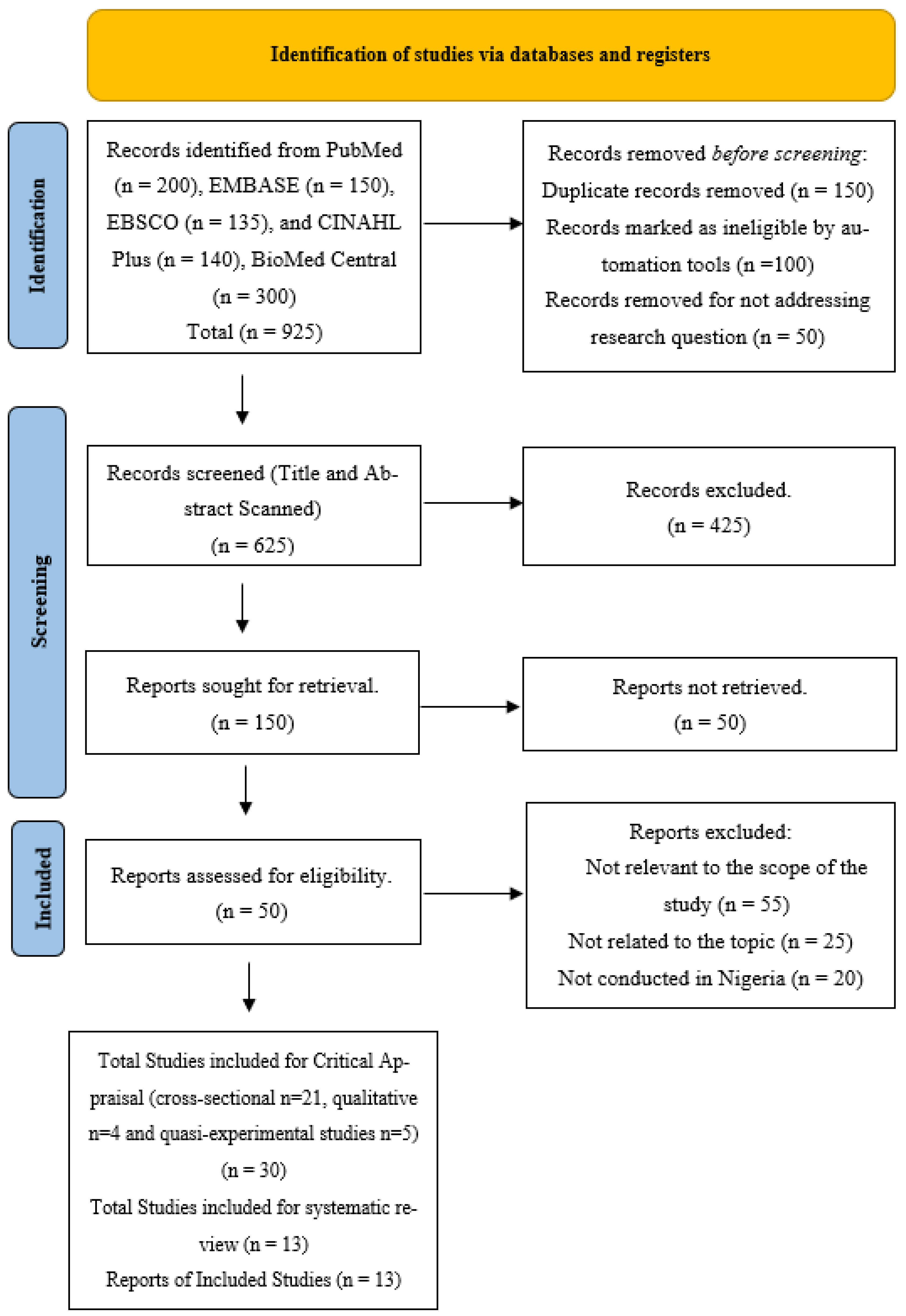

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Critical Appraisal

2.5.1. Critical Appraisal and Ethical Appraisal Outcome

2.5.2. Data Abstraction

2.6. Data Analysis

| Qualitative Studies: CASP Tool | Section A: Are the Results Valid? | Section B: What Are the Results? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Was There a Clear Statement of the Aims of the Research? | Is a Qualitative Methodology Appropriate? | Was the Research Design Appropriate to Address the Aims of the Research? | Was the Recruitment Strategy Appropriate to the Aims of the Research? | Were the Data Collected in a Way that Addressed the Research Issue? | Has the Relationship between the Researcher and Participants Been Adequately Considered? | Have Ethical Issues Been Taken into Consideration? | Was the Data Analysis Sufficiently Rigorous? | Is There a Clear Statement of Findings? | How Valuable is the Research? |

| Tomlinson 2022 [28] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Obioma et al., 2015 [29] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Salau and Ogunfowokan 2017 [30] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Adegbayi 2017 [31] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Introduction | Methods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Were the Aims/Objectives of the Study Clear? | Was the Study Design Appropriate for the Stated Aim(s)? | Was the Sample Size Justified? | Was the Target/Reference Population Clearly Defined? (Is It Clear Who the Research Was About?) | Was the Sample Frame Taken from an Appropriate Population Base So That It Closely Represented the Target/Reference Population under Investigation? | Was the Selection Process Likely to Select Subjects/Participants That Were Representative of the Target/Reference Population under Investigation? | Were Measures Undertaken to Address and Categorise Non-Responders? | Were the Risk Factor and Outcome Variables Measured Appropriate to the Aims of the Study? | Were the Risk Factor and Outcome Variables Measured Correctly Using Instruments/Measurements That Had Been Trialled, Piloted, or Published Previously? | Is It Clear What was Used to Determine Statistical Significance and/or Precision Estimates? (e.g., p-Values, Confidence Intervals) |

| Rasheed and Afolabi 2021 [26] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gorah, Haruna and Ufwil 2020 [20] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Jimin et al., 2023 [5] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Fehintola et al., 2017 [18] | + | + | + | + | +/- | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| Edet et al., 2020 [19] | + | + | +/- | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Umahi et al., 2021 [15] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + |

| Okafor-Terver & Chuemchit, 2017 [32] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Nkemdilim, Nwosu and Chris 2023 [33] | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | +/- | + |

| Nwimo et al., 2022 [34] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- |

| Emmanuel and Amadaowei 2020 [35] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Isah, Ibrahim and Aminu 2022 [36] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Ilo, Nwimo and Chinagorom 2016 [4] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Bolanle, Ayoade and Sola 2021 [37] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ekoko and Ikolo 2021 [9] | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | - | + |

| Buradum, Etor and Edison 2020 [38] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Popoola et al., 2021 [39] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Obande-Ogbuinya et al., 2022 [23] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Idoko et al., 2022 [40] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Okeke et al., 2021 [41] | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + | + |

| Garba, Rabiu and Abubakar 2018 [22] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ibeagha 2022 [21] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Results | Discussion | Others | ||||||||

| Reference | Were the Methods (Including Statistical Methods) Sufficiently Described to Enable Them to Be Repeated? | Were the Basic Data Adequately Described? | Does the Response Rate Raise Concerns about Non-Response Bias? | If Appropriate, Was Information about Non-Responders Described? | Were the Results Internally Consistent? | Were the Results Presented for All the Analyses Described in the Methods? | Were the Authors’ Discussions and Conclusions Justified by the Results? | Were the Limitations of the Study Discussed? | Were There Any Funding Sources or Conflicts of Interest that May Affect the Authors’ Interpretation of the Results? | Was Ethical Approval or Consent of Participants Obtained? |

| Rasheed and Afolabi 2021 [26] | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | + | + |

| Gorah, Haruna and Ufwil 2020 [20] | + | + | +/- | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Jimin et al., 2023 [5] | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Fehintola et al., 2017 [18] | + | + | +/- | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Edet et al., 2020 [19] | + | + | +/- | - | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Umahi et al., 2021 [15] | + | + | - | + | + | + | +/- | - | + | + |

| Okafor-Terver & Chuemchit, 2017 [32] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Nkemdilim, Nwosu and Chris 2023 [33] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Nwimo et al., 2022 [34] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Emmanuel and Amadaowei 2020 [35] | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Isah, Ibrahim and Aminu 2022 [36] | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Ilo, Nwimo and Chinagorom 2016 [4] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bolanle, Ayoade and Sola 2021 [37] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Ekoko and Ikolo 2021 [9] | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + | + | + |

| Buradum, Etor and Edison 2020 [38] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + |

| Popoola et al., 2021 [39] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Obande-Ogbuinya et al., 2022 [23] | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Idoko et al., 2022 [40] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Okeke et al., 2021 [41] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- |

| Garba, Rabiu and Abubakar 2018 [22] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | + | + |

| Ibeagha 2022 [21] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| JBI Checklist Criteria (Potential Bias and Threat) | Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ogunleye and Kio 2020 [2] | Agbede and Ekeanyanwu 2021 [6] | Chinasa and Catherine 2021 [42] | Adegoke and Janet 2022 [43] | Omovie, Agbapuonwu and Makata 2021 [44] | |

| No (-) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| No (-) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | No (-) |

| No (-) | Yes (+) | No (-) | Yes (+) | No (-) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) | Yes (+) |

| Total (%) and quality rating | 8/9 (88%) Good | 8/9 (88%) Good | 8/9 (88%) Good | 8/9 (88%) Good | 8/9 (88%) Good |

3. Results

3.1. Included Study Characteristics

3.2. Included Study Designs

3.3. Information Regarding Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Regarding Menstruation

3.4. Summary of Findings

3.4.1. Knowledge of Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene including Sources of Information Regarding Menstruation

“Upon my initial encounter with menstruation, I found myself perplexed and questioning its nature. I experienced apprehension in disclosing this information, uncertain of how others could respond, potentially including ridicule or similar reactions”.[28]

“Subsequently, I informed my mother regarding the matter, to which she responded by instructing me on the proper use of menstrual pads, demonstrating the appropriate technique”.[28]

3.4.2. Attitude towards Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene

“No, I did not anticipate the occurrence and was there at my educational institution when the incident transpired. Upon observing the emergence of blood, I emitted vocal expressions of distress. According to my mother, I underwent a process of growth and development as a female child, resulting in my maturation”.[28]

“I experienced a significant level of fear and promptly informed my mother, who advised me to go with bathing and exercise caution in the event of physical contact, as it may potentially result in pregnancy”.[28]

“No, I may choose not to disclose this information to guys. However, if they become aware, they express a preference for not being touched by a menstrual girl. Furthermore, they indicated that if I were to touch them, they would withhold payment. According to popular belief, women possess significant power and have the ability to deprive males of certain privileges or possessions, thereby prompting my decision to depart”.[28]

“My mother exhibited a high level of enthusiasm, to the extent that she slaughtered a chicken and prepared jollof rice to cater to the entire household”.[31]

3.4.3. Practice Regarding Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene

“Upon becoming aware of the situation, she assumed a seated position and proceeded to articulate statements designed to instil fear and dissuade me from engaging with individuals of the male gender. For instance, she posited that physical contact in the form of a hug with a male counterpart could result in an unintended pregnancy, among other related notions”.[31]

4. Discussion of Findings

4.1. Knowledge of Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene including Sources of Information Regarding Menstruation

4.2. Attitude towards Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene

4.3. Practices of Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Recommendations for Future Research/Practice/Policy

- Standardisation of sensitisation practices across public and private primary and junior secondary schools for teenage girls about menstruation and menstrual hygiene. Such actions promise improvement of interventions against many of the myths advanced about menarche and the onset of menstruation for girls.

- Additional efforts should be placed towards enlightening girls about proper methods of hygiene and menstrual health once they reach this phase. Such actions would help better secure the overall reproductive health of young girls, while also helping them address many related concerns, such as how to properly dispose of used pads and tampons.

- Governments and other non-governmental institutions within the country can also partner more closely to ensure enhanced availability of menstruation supplies, including pads and tampons, amongst more underprivileged sections of the population. By working together more closely, such institutions can improve their reach effectively.

- The prevalence of negative attitudes suggests a lack of comprehensive understanding among the respondents in the study area. Future research endeavours should prioritise the teaching and enlightenment of teenage girls and women about the significance of menstrual hygiene.

- A notably deficient level of knowledge and awareness regarding the disposal of menstrual waste, particularly the notion that a dustbin is not required, was indicated. Schools must implement educational programmes aimed at sensitising and empowering students, both girls and boys, about menstruation. These programmes should address the challenges related to menstrual hygiene, including waste collection, segregation, storage, and disposal, as well as addressing taboos associated with menstruation and the potential blockages of toilets due to the disposal of used napkins.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, A.K.; Lichtman, A.H.; Pillai, S. Cellular and Molecular Immunology, 8th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunleye, O.R.; Kio, J.O. Nursing Intervention on Knowledge of Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescents in Irepodun-Ifelodun Local Government of Ekiti State. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Arts Sci. 2020, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Education and Provisions for Adequate Menstrual Hygiene Management at School can Prevent Adverse Health Consequences. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/27-05-2022-education-and-provisions-for-adequate-menstrual-hygiene-management-at-school-can-prevent-adverse-health-consequences (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Ilo, C.I.; Nwimo, I.O.; Onwunaka, C. Menstrual Hygiene Practices and Sources of Menstrual Hygiene Information among Adolescent Secondary School Girls in Abakaliki Education Zone of Ebonyi State. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jimin, S.; Felix, I.; Faith, L.; Olufemi, O.; Olugbenga, A.; Kumolu, G.; Osinowo, O. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Menstrual Hygiene Management among Orphan and Vulnerable Adolescents in Lagos State. Int. J. Gend. Stud. 2023, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbede, C.O.; Ekeanyanwu, U.C. An outcome of educational intervention on the menstrual hygiene practices among schoolgirls in Ogun State, Nigeria: A quasi-experimental study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, S.; Hamory, J.; Gezahegne, K.; Pincock, K.; Woldehanna, T.; Yadete, W.; Jones, N. Improving Menstrual Health Literacy Through Life-Skills Programming in Rural Ethiopia. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 838961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J.L.; Haver, J.; Mendoza, P.; Vargas Kotasek, S.M. The More You Know, the Less You Stress: Menstrual Health Literacy in Schools Reduces Menstruation-Related Stress and Increases Self-Efficacy for Very Young Adolescent Girls in Mexico. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2022, 3, 859797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekoko, O.N.; Ikolo, V.E. Menstrual Hygiene Literacy Campaign Among Secondary School Girls in Rural Areas of Delta State, Nigeria. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2021, 5904. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5904 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Mcgawley, K.; Sargent, D.; Noordhof, D.; Badenhorst, C.E.; Julian, R.; Govus, A.D. Improving menstrual health literacy in sport. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, A.M.; Sivakami, M.; Thakkar, M.B.; Bauman, A.; Laserson, K.F.; Coates, S.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. Open 2016, 6, e010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennegan, J.; Dolan, C.; Steinfield, L. Menstruation and the cycle of poverty: A cluster quasi-randomised control trial of sanitary pad and puberty education provision in Uganda. Public Libr. Sci. One 2017, 12, e0188456. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M.; Caruso, B.A.; Sahin, M.; Calderon, T.; Cavill, S.; Mahon, T.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. A time for global action: Addressing girls’ menstrual hygiene management needs in schools. Public Libr. Sci. Med. 2017, 14, e1002302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Larsen-Reindorf, R.E. Menstrual knowledge, sociocultural restrictions, and barriers to menstrual hygiene management in Ghana: Evidence from a multi-method survey among adolescent schoolgirls and schoolboys. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umahi Nnennaya, E.; Atinge, S.; Paul Dogara, S.; Joel Ubandoma, R. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in Taraba State, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.L.; Harris, B.; Onuegbu, C.; Griffiths, F. Systematic review of educational interventions to improve the menstrual health of young adolescent girls. Br. Med. J. Open 2022, 12, e057204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulto, G.A. Knowledge on Menstruation and Practice of Menstrual Hygiene Management Among School Adolescent Girls in Central Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehintola, F.O.; Fehintola, A.O.; Aremu, A.O.; Idowu, A.; Ogunlaja, O.A.; Ogunlaja, I.P. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice about menstruation and menstrual hygiene among secondary high school girls in Ogbomoso, Oyo state, Nigeria. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 6, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edet, O.B.; Bassey, P.E.M.; Esienumoh, E.E.; Ndep, A.O. An exploratory study of menstruation and menstrual hygiene knowledge among adolescents in urban and rural secondary schools in cross river State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2020, 23, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Gorah, K.Y.; Haruna, E.A.; Ufwil, J.J. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Menstrual Hygiene Management of Female Students in Bokkos Local Government Area of Plateau State; Nigeria. KIU J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeagha, N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Menstrual Hygiene Among Public Secondary School Students in Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo State. Niger. Acad. Forum 2022, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Garba, I.; Rabiu, A.; Abubakar, I.S. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls in Kano, Nigeria. Trop. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 35, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obande-Ogbuinya, N.E.; Chikezie, O.D.; Bassey, O.J.-P.; Chinemerem, A.J.; Edward, O.C.; Uzoho, C.M.; Omaka-Amari, L.N.; Nwafor, J.N.; Aleke, C.O.; Nweke, O.J.; et al. Knowledge and menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent secondary school girls in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2022, 9, 3075–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Deshpande, T.; Gharai, S.; Patil, S.; Durgawale, P. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls—A study from urban slum area. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, K.; Curry, C.; Sherry Ferfolja, T.; Parry, K.; Smith, C.; Hyman, M.; Armour, M. Adolescent Menstrual Health Literacy in Low, Middle and High-Income Countries: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, T.O.; Afolabi, W.A. Maternal and Adolescent Factors Associated with Menstrual Hygiene of Girls in Senior Secondary Schools in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Matern. Child Health 2021, 6, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, M.M. A Mixed Methods Assessment of Menstrual Hygiene Management and School Attendance among Schoolgirls in Edo State, Nigeria. 2022. Available online: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5284&context=etd (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Obioma, N.; Nkadi, O.; Temitayo, O.; Femi, A. An Assessment of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Secondary Schools. 2015. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/1256/file/Assessment-menstrual-hygiene-management-in-secondary-schools-2.jpg.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Salau, O.R.; Ogunfowokan, A.A. Pubertal Communication Between School Nurses and Adolescent Girls in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegbayi, A. Blood, joy and tears: Menarche narratives of undergraduate females in a selected in Nigeria Private University. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2017, 31, 20170023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okafor-Terver, I.S.; Chuemchit, M. Knowledge, belief and practice of menstrual hygiene management among in-school adolescents in Katsina state, Nigeria. J. Health Res. 2017, 31, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkemdilim, E.; Nwosu, U.; Chris, G.A. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Menstrual Hygiene Management Among Adolescent Girls And Young Women In An Internally Displaced Person Camp In Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria. J. Res. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2023, 11, 1–9. Available online: https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol11-issue5/11050109.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Nwimo, I.O.; Elom, N.A.; Ilo, C.I.; Ezugwu, U.A.; Ezugwu, L.E.; Nkwoka, I.J.; Igweagu, C.P.; Okeworo, C.G. Menstrual hygiene management practices and menstrual distress among adolescent secondary school girls: A questionnaire-based study in Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, E.N.; Amadaowei, F. Attitude Towards Menstrual Hygiene Practices Among Female Secondary School Students In Khana, Rivers State, Nigeria. Int. J. Pure App. Sci. 2020, 19, 10. Available online: https://www.cambridgenigeriapub.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CJPAS_Vol18_No9_Sept_2020-8.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Isah, S.; Ibrahim, F.; Aminu, Y. Relationship between Knowledge of Health Consequences and Practice of Menstrual Hygiene among Female Students of Selected Secondary Schools in Bauchi State. Afr. J. Hum. Contem. Edu. Res. 2022, 8, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bolanle, F.Z.; Ayoade, T.M.; Sola, A.O. Knowledge and Menstrual Hygiene Practices among Adolescent Female Apprentices in Lagelu Local Government Area, Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2021, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buradum, U.A.; Etor, N.E.; Edison, O.S. Knowledge of Menstrual Hygiene Among Female Secondary School Students in Khana, Rivers State, Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Healthc. Res. 2020, 8, 1–6. Available online: www.seahipaj.org (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Popoola, M.O.; Popoola, O.B.; Mohammed, B.; Anisa, A.; Jimoh, A.O. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Menstrual Hygiene Amongst Female Secondary School Students in Kaduna State. J. Med. Women’s Assoc. Niger. 2021, 6, 1. Available online: http://www.jmwan.org (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Idoko, L.O.; Okafor, K.C.; Ayegba, V.O.; Bala, S.; Evuka, V.B. Knowledge and Practice of Menstrual Health and Hygiene among Young People in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 12, 292–308. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/ojog_2022042414402773.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Okeke, K.M.; Charles-Unadike, V.O.; Fidelis, M.N.; Nwachukwu, K.C. Menstrual Hygiene Practices among Secondary School Girls in Owerri Municipal Council of Imo State, Nigeria. Int. J. Hum. Kinet. Health Educ. 2021, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chinasa, U.E.; Catherine, O.A. Effect of Peer-Led and Parent-Led Education Interventions on Menstrual Hygiene-Related Knowledge of In-School Adolescent Girls in Ogun State, Nigeria. Int. J. Public Health Pharmacol. 2021, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, R.A.; Kio, J. Intervention Study on Practice of Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescents in Two Selected Secondary Schools, Lagos State. Int. J. Med. 2022, 3, 215–228. Available online: https://www.ijmnhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IJMNHS.com-3.2-17-2022-Intervention-Study-on-Practice-of-Menstrual-Hygiene-Among-Adolescents-in-Two-Selected-Secondary-Schools-Lagos-State.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Omovie, L.C.; Agbapuonwu, N.E.; Makata, N.E. Effectiveness of Structured-Teaching-Programme on Adolescents’ Knowledge of Early Pubertal Changes and Menstrual Hygiene in Selected Secondary Schools in Sapele, Delta State, Nigeria. Int. J. Res. 2021, 6, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igras, S.M.; Macieira, M.; Murphy, E.; Lundgren, R. Investing in very young adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health. Glob. Public Health 2014, 9, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Patel, S.V. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene, and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low-and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaim, J. Exist or exit? Women business-owners in Bangladesh during COVID-19. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demisse, T.L.; Aliyu, S.A.; Kitila, S.B.; Tafesse, T.T.; Gelaw, K.A.; Zerihun, M.S. Utilization of preconception care and associated factors among reproductive age group women in Debre Birhan town, North Shewa, Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sully, E.A.; Biddlecom, A.; Darroch, J.E.; Riley, T.; Ashford, L.S.; Lince-Deroche, N.; Murro, R. Adding It up: Investing in Sexual and Reproductive Health; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A.E.; Bouman, W.P.; Brown, G.R.; De Vries, A.L.; Deutsch, M.B.; Arcelus, J. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int. J. Transgender Health 2022, 23, 1–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Olabanjo, O.O.; Olorunfemi, A.O.; Phillips, A.; Temitope, O.O. Knowledge, practices and socio-cultural restrictions associated with menstruation and menstrual hygiene among in-school adolescents in South Africa. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 16, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lawan, U.M.; Nafisa, W.Y.; Aisha, B.M. Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene amongst Adolescent School Girls in Kano, Northwestern Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2018, 3, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Parle, J.; Khatoon, Z. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perception about menstruation and menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls in rural areas of Raigad district. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 2490–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbesu, E.W.; Asgedom, D.K. Menstrual hygiene practice and associated factors among adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Cent. Public Health 2023, 23, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, G.H. Menstrual hygiene management practices and associated factors among secondary school girls in East Hararghe Zone, Eastern Ethiopia. Adv. Public Health 2020, 2020, 8938615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Nabwera, H.M.; Sosseh, F.; Jallow, Y.; Comma, E.; Keita, O.; Torondel, B. A rite of passage: A mixed methodology study about knowledge, perceptions, and practices of menstrual hygiene management in rural Gambia. BioMed Cent. Public Health 2019, 19, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtegiorgis, Y.; Sisay, T.; Kloos, H.; Malede, A.; Yalew, M.; Arefaynie, M.; Adane, M. Menstrual hygiene practices among high school girls in urban areas in Northeastern Ethiopia: A neglected issue in water, sanitation, and hygiene research. Public Libr. Sci. One 2021, 16, e0248825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajari, E.; Abass, T.; Ilesanmi, E.; Adebisi, Y. Cost Implications of Menstrual Hygiene Management in Nigeria and Its Associated Impacts. Preprints 2021, 2021050349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.S.; Willi, W.; Abubeker, A. Factors affecting menstrual hygiene management practice among school adolescents in Ambo, Western Ethiopia, 2018: A cross-sectional mixed-method study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S stands for Sample | Adolescents going to schools in Nigeria |

| PI stands for Phenomenon of Interest | Menstruation literacy, menstruation hygiene |

| D stands for Design | Questionnaire, intervention, interview, focus group discussions (FGDs), survey |

| E stands for Evaluation or outcome | Knowledge of menstruation and menstrual hygiene, sources of information regarding menstruation, attitude towards menstruation, perception of menstruation, practices, and beliefs of menstruation hygiene |

| R stands for Research type | Quantitative, cross-sectional, quasi-experimental, qualitative |

| Date | Database | Keywords | Strategy | Results (Hits) | Refine | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2023 | PubMed | Adolescent OR girl | Use of Boolean OR | 200 | Last 5 years and peer-reviewed journals = 50 | 7 articles were useful. 3 reviews of literature. 3 systematic reviews. Key references added. |

| 6 June 2023 | EMBASE | Youth OR young | Use of Boolean OR | 150 | Last 5 years and peer-reviewed journals = 40 | 5 articles were useful. 2 reviews of literature. 2 systematic reviews. Key references added. |

| 9 June 2023 | EBSCO | Menstrual health literacy OR Information | Use of Boolean OR | 135 | Last 5 years and peer-reviewed journals = 30 | 7 studies looked useful. 3 reviews of literature. 3 systematic reviews. Key references added. |

| 15 June 2023 | CINAHL Plus | Attitude AND Practice | Use of Boolean AND | 140 | Last 5 years and peer-reviewed journals = 25 | 5 studies looked useful. 2 reviews of literature. 1 systematic review. Key references added. |

| 10 July 2023 | BioMed Central | Schoolgirls AND in-school adolescents | Use of Boolean AND | 300 | Last 5 years and peer-reviewed journals = 15 | 6 articles were okay. 3 reviews of literature. 1 systematic review. References added. |

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample (S) | Adolescents (age 10–19) attending secondary schools in Nigeria | Adolescents (age 10–19) not attending secondary schools in Nigeria |

| Phenomenon of Interest (PI) | Menstruation, menstrual literacy, menstrual hygiene | Articles that did not research menstruation, menstrual literacy, menstrual hygiene |

| Design (D) | Questionnaire, intervention research, interviews, focus-group discussions, survey | Case study, cohort study, randomised control trials (RCTs) |

| Evaluation (E) outcome | Knowledge of menstruation and menstrual hygiene, sources of information regarding menstruation, attitude towards menstruation, practices, and beliefs of menstruation hygiene | Articles that did not measure outcomes regarding knowledge of menstruation and menstrual hygiene, sources of information regarding menstruation, attitude towards menstruation, practices, and beliefs of menstruation hygiene |

| Research type (R) | Primary research, peer-reviewed, quantitative studies, qualitative studies, cross-sectional studies, quasi-experimental studies that had a component of menstrual information, studies that included adolescents up to the age of 19, no timeframe, published in English language | Not peer-reviewed, articles that are not primary research, systematic reviews, commentaries, letters to editors, short communications, studies aimed at adult women |

| Reference | Study Setting | Study Design, Sample Size | Aim | Study Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomlinson 2022 [28] | Suburb settlements located in Benin City in Edo State, Nigeria | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative, such as in-depth interviews and questionnaires). 60 girls for the interview and 600 girls for the questionnaire (between 11 and 19 years). | To elucidate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices about menstruation among young female students. | The mean age of onset of menarche was found to be 13.1 years, with the prevailing symptoms reported as abdominal discomfort in 73.7% of cases and mood irritation in 40.7% of cases. Knowledge about menstruation was obtained from their mothers. 76.9% of participants answered correctly when basic questions were asked. 42.6% of the girls had anxiety for their next period. 4.7% of respondents had adequate menstrual practice at school which included the use of sanitary pads and sanitation facilities. | No longitudinal data for causal inference. Selection bias when selecting only in-school adolescents as outcomes may not reflect the broader population. Information bias as respondents were too scared to ask for clarification of questions. Exposure or outcome misclassification. Social desirability bias by girls exaggerating negative experiences. Only adolescent girls were used and the influence of other counterparts such as males and teachers was not considered. |

| Adegbayi 2017 [31] | Redeemer’s University, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria | Quantitative method using questionnaires and qualitative method using in-depth interviews. 136 undergraduate female students aged between 16 and 25 years. | To investigate the many sources of menstrual knowledge and the practices used throughout the menstrual cycle. | Most respondents (95%) reported that they obtained knowledge about menstruation from their mothers, female relatives, and school classes before experiencing their first menstrual period. | The study’s representativeness of the entire population may be limited due to its exclusive selection from a private university, where most of the female participants are from the upper middle class and possess a higher socio-economic position. |

| Agbede and Ekeanyanwu 2021 [33] | Four secondary schools in Ogun State, Nigeria | Quasi-experimental using an educational intervention where data were collected using a researcher-structured questionnaire. 120 in-school adolescent girls. | To ascertain the impact of a training programme on menstrual hygiene practices. | At the end of the intervention, menstrual hygiene practice levels increased. | The study’s conclusions were derived from an examination of traditional and cultural variables that could potentially contribute to increased representation of the Nigerian populace. |

| Bolanle, Ayoade and Sola 2021 [37] | Lagelu Local Government Area in Oyo State, Nigeria | Descriptive cross-sectional study using a semi-structured questionnaire. A total of 421 female adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 years old were selected. | To examine the extent of awareness and adherence to sanitary menstrual practices among adolescents. | Approximately 50.8% of individuals exhibited a satisfactory level of understanding regarding the topic of menstruation. The study revealed a significant lack of hygiene knowledge, with just 22.6% of participants demonstrating an accurate understanding that monthly blood originates from the uterus. Additionally, most participants (55.5%) were unaware of the typical duration of the menstrual cycle. A total of 42.2% of the participants indicated their preference for utilising washable and reusable materials. | Most community settings do not have infrastructures for safe and private menstrual hygiene and the ones that are present are underequipped or mismanaged. |

| Ekoko and Ikolo 2021 [9] | Rural community secondary schools in Delta State, Nigeria | Cross-sectional descriptive study. 471 female students between the ages of 10 and 19. | To enhance the level of menstrual hygiene awareness and foster positive attitudes regarding menstruation hygiene and periods among secondary school girls residing in rural parts of Delta State, Nigeria. | A significant proportion of teenagers, specifically 290 individuals (61.5%) and 369 individuals (78.3%), respectively, demonstrated a lack of knowledge of the concept of menstruation and its underlying causes. Out of the whole sample population, it was observed that 213 individuals, accounting for 45% of the female participants, initially utilised a washable cloth as a means of managing menstruation. | Adolescents were not ready for the menstruation experience which resulted in limited knowledge of how to use and dispose of absorbent materials. |

| Fehintola et al., 2017 [18] | Public secondary schools in Ogbomoso North Local Government Area (LGA) of Oyo State, Southwest Nigeria | Cross-sectional study. 447 respondents between the ages of 10 and 19 were selected. | To evaluate the level of understanding, attitudes, and behaviours about menstruation and menstrual hygiene. | Most participants (96.42%) were aware of menarche before experiencing menstruation, with the primary source of this knowledge being their mothers (41.83%). Most of the participants (55.92%) had a satisfactory level of understanding regarding menstruation and menstrual hygiene. | The causal conclusion is limited due to the study being cross-sectional. Information bias as the study was based on self-reported information on menstruation. |

| Obande-Ogbuinya et al., 2022 [23] | Secondary school girls in Ikwo local government area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria | A cross-sectional descriptive study using an administered questionnaire. 315 participants were recruited for the research. | To determine the knowledge and attitude toward menstrual hygiene practices among adolescents. | Of most teenage girls, 266 (84.4%) indicated that they changed sanitary pads after 6 h and 269 (85.4%) were positive that the genital tract should be washed with water during menstruation. 264 Respondents (83.8%) were aware that genital tracts should be washed from front to back during menstruation, and 259 (83.2%) of the adolescent girls indicated that sanitary pads should be disposed of immediately after use. | Cause-and-effect relationships might not be shown between study variables due to the nature of the study, which is cross-sectional. |

| Okafor-Terver & Chuemchit, 2017 [32] | Secondary schools in Katsina State, Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey. 395 female adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19. | To assess the knowledge, beliefs, and practice of menstruation among in-school adolescents in Katsina State, Nigeria | 59.7% of respondents did not know what causes menses, the channels through which menses flow, and the duration of time between menstrual cycles. Only 39.7% of participants had basic knowledge about menses. Also, 62.3% use commercial pads; 10.8% and 26.9% use tissues and cloths. 86% wash their rags with water and soap and 35% dry them under the sun while others dry them under the bed or in their room. | The use of Hausa, which is the local language, to design the questionnaire and the enthusiasm of the Muslim conservative girls to take part in the research, who are conservative in nature. The study cannot be generalised in Nigeria and other countries. |

| Buradum, Etor and Edison 2020 [38] | Secondary schools in Khana, Rivers State, Nigeria | Descriptive cross-sectional survey design using a questionnaire. 250 female students were recruited for the study. | To examine knowledge of menstrual hygiene practices among female secondary school students. | Findings indicated that 55.8% of the population had adequate knowledge of menstrual hygiene. Approximately 33.9% of the participants possessed knowledge regarding the typical length of a menstrual cycle, which is 27 days, while more than half (66.1%) indicated 28 days. | There was no proper explanation on how to calculate the menstrual cycle, which could be of help to the respondents. |

| Gorah, Haruna and Ufwil 2020 [20] | Secondary schools in Bokkos Local Government Area, Plateau State | Survey research design. 325 female adolescents | To examine the knowledge, attitude, and practices of female students regarding menstrual hygiene. | Respondents had good knowledge of the information about menstruation from their mothers (85.24%) and had low knowledge of the need to dispose of pads in bins (34.42%). Participants had negative attitudes towards menstrual hygiene. | Absenteeism of girls from school. No generalisability of results. |

| Ibeagha 2022 [21] | Public secondary schools in Akinyele Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria | Descriptive research design. 1200 female junior and senior secondary school adolescents. | To investigate female adolescents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding proper menstrual hygiene and menstruation. | The findings indicate a lack of substantial understanding regarding menstrual hygiene among secondary school students (p > 0.05). Furthermore, there is a notable absence of positive attitudes towards menstrual hygiene and a lack of adherence to menstrual hygiene practices. | The study was conducted within a single state, hence constraining the generalisability of its findings. Relevant conclusions cannot be established as well. |

| Okeke et al., 2021 [41] | Secondary schools in Owerri Municipal Council of Imo State, Nigeria | Descriptive survey research design using a structured validated questionnaire. 420 female adolescent girls. | Menstrual hygiene practices were examined among in-school adolescents in Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. | Menstrual hygiene practice was reported by almost half (45.5%) of the respondents. Additionally, it was found that a significant proportion of female students in secondary school engage in menstrual hygiene practices. Specifically, 46.8% of girls aged 10–14, 45% of girls aged 15–19, and 45% of girls aged 19 and above reported practising menstrual hygiene. | The population was from the urban area of the state, which is not representative of the rural population. |

| Edet et al., 2020 [19] | Eight secondary schools were selected from two Local Government Areas (urban and rural) in Cross-River State, Nigeria | Exploratory descriptive cross-sectional design. 1006 female students aged between 10 and 18 years. | To determine menstruation and menstrual hygiene knowledge among secondary school adolescents as a step to plan an appropriate health promotion intervention. | Among the participants, it was observed that a majority of rural-based teenage female students (56.7%) exhibited a notable deficiency in their understanding of menstruation and menstrual hygiene practices, in contrast to the urban-based respondents (42.2%). Data on menstruation were collected from the mothers of urban respondents, with a total of 435 individuals representing 72.5% of the sample. Similarly, for rural participants, data were received from the mothers of 327 individuals, accounting for 80.5% of the sample. Furthermore, it was shown that most teenagers were in both urban schools (67.8%). | The results obtained from this research are limited in their applicability to Cross-River State and cannot be extrapolated to other states within Nigeria. The subject matter of bias in response pertains to a delicate societal matter within the field of research. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uzoechi, C.A.; Parsa, A.D.; Mahmud, I.; Alasqah, I.; Kabir, R. Menstruation among In-School Adolescent Girls and Its Literacy and Practices in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122073

Uzoechi CA, Parsa AD, Mahmud I, Alasqah I, Kabir R. Menstruation among In-School Adolescent Girls and Its Literacy and Practices in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Medicina. 2023; 59(12):2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122073

Chicago/Turabian StyleUzoechi, Chinomso Adanma, Ali Davod Parsa, Ilias Mahmud, Ibrahim Alasqah, and Russell Kabir. 2023. "Menstruation among In-School Adolescent Girls and Its Literacy and Practices in Nigeria: A Systematic Review" Medicina 59, no. 12: 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122073

APA StyleUzoechi, C. A., Parsa, A. D., Mahmud, I., Alasqah, I., & Kabir, R. (2023). Menstruation among In-School Adolescent Girls and Its Literacy and Practices in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Medicina, 59(12), 2073. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122073