Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Physicians (2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Questionnaire

- Main demographic data: age, gender, seniority, kind of medical background (i.e., general practitioner, emergency department, internal medicine, neurology, psychiatry, or other), and the Italian region where the professional mainly worked and lived;

- Knowledge test: According to the medical applications of health belief model (HBM) [46,47,48,49,50], knowledge status of a certain professional about a specific topic is key determinant of attitudes and behaviors, which in this specific case leads to the appropriate management of N2O abuse cases. In order to ascertain the knowledge status of participants, they received a total of 20 statements about N2O, including 16 dichotomous items (e.g., “N2O irreversibly inactivates vitamin B12”; TRUE) and 4 polytomous ones (e.g., “Chronic abuse of N2O is frequently associated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) anomalies…” (a) of the cerebral cortex; (b) of the brainstem; (c) of the cervical spinal cord; or (d) of the thorax spinal cord; correct answer = c); the survey was therefore designed through an extensive review of the medical literature [1,2,3,12,13,20,28,30]. More precisely, most of the items were identified through the analysis of the recent report from EMCDDA [8]. In order to ascertain whether the items regarding the knowledge were able to properly discriminate between participants with “strong” and “weak” understanding of N2O abuse, the approach suggested by Möltner and Jünger was applied [51,52]. Briefly, the correlation of each item of the knowledge test with the sum of all corrected answers was assessed through Spearman’s rank test; all questions with a rho ≥ 0.4 were included in a summary score (knowledge score; GKS). In accord with the original model provided by the studies of Betsch and Wicker [46] and Zingg and Siegrist [45], in order to stress the appropriate answers over the inappropriate ones and the lack of knowledge over a specific topic, GKS was calculated by adding +1 to the sum score for every correct answer, whereas a wrong indication or a missing/“don’t know” answer added 0;

- Risk perception: According to the original report from Yates [49], perceived risk can be defined by the perceived probability of a certain event (F) and the expected consequences of that event (C). Participants were therefore requested to rate the perceived severity (CN2O) and the perceived frequency (FN2O) of N2O recreational abuse in the Italian population by means of a fully labeled 5-point Likert scale (range: from “not significant” with a score of 1 to “very significant” with a score of 5). A cumulative risk perception score (RPS) was therefore calculated as follows:Respondents were then asked to rate how difficult they perceived the management of N2O abuse in Italian settings compared to other abuse substances, including cocaine, opioids, cannabinoids, and amphetamines. All of the aforementioned disorders were rated 1 (not difficult) to 10 (very difficult);CN2O × FM2O = RPS

- Attitudes: For the aims of the present study, the attitude was acknowledged as the tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor [53]. Therefore, reporting a certain attitude involved the expression of an evaluative judgment about a certain item. Respondents were therefore requested to rate, through a full Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree), whether or not they perceived N2O abuse cases as a likely occurrence during daily activities in the following months. Through a subsequent item, they were asked whether or not they perceived N2O as potentially affecting daily working activities and whether or not they were confident of being able to recognize a N2O abuse case;

- Practices: Participants were requested to report whether or not they had received any previous medical formation on N2O abuse and its management and whether they had previously managed any case of N2O abuse (ever vs. never).

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Knowledge Test

3.3. Risk Perception

3.4. Attitudes

3.5. Univariate Analysis

3.6. Multivariable Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Results

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item No. | Recommendation | Page | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract. | 1 |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found. | 1 | ||

| Introduction | |||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported. | 1–3 |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses. | 2–3 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper. | 3 |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection. | 3 |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants. | 3–4 |

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable. | 3–4 |

| Data sources/measurement | 8 | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group. | 4–6 |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias. | 4–5 |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at. | 4 |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why. | 5–6 |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding. | 5–6 |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions. | 5–6 | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed. | 5–6 | ||

| (d) If applicable, describe analytical methods, taking account of sampling strategy. | 5–6 | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses. | - | ||

| Results | |||

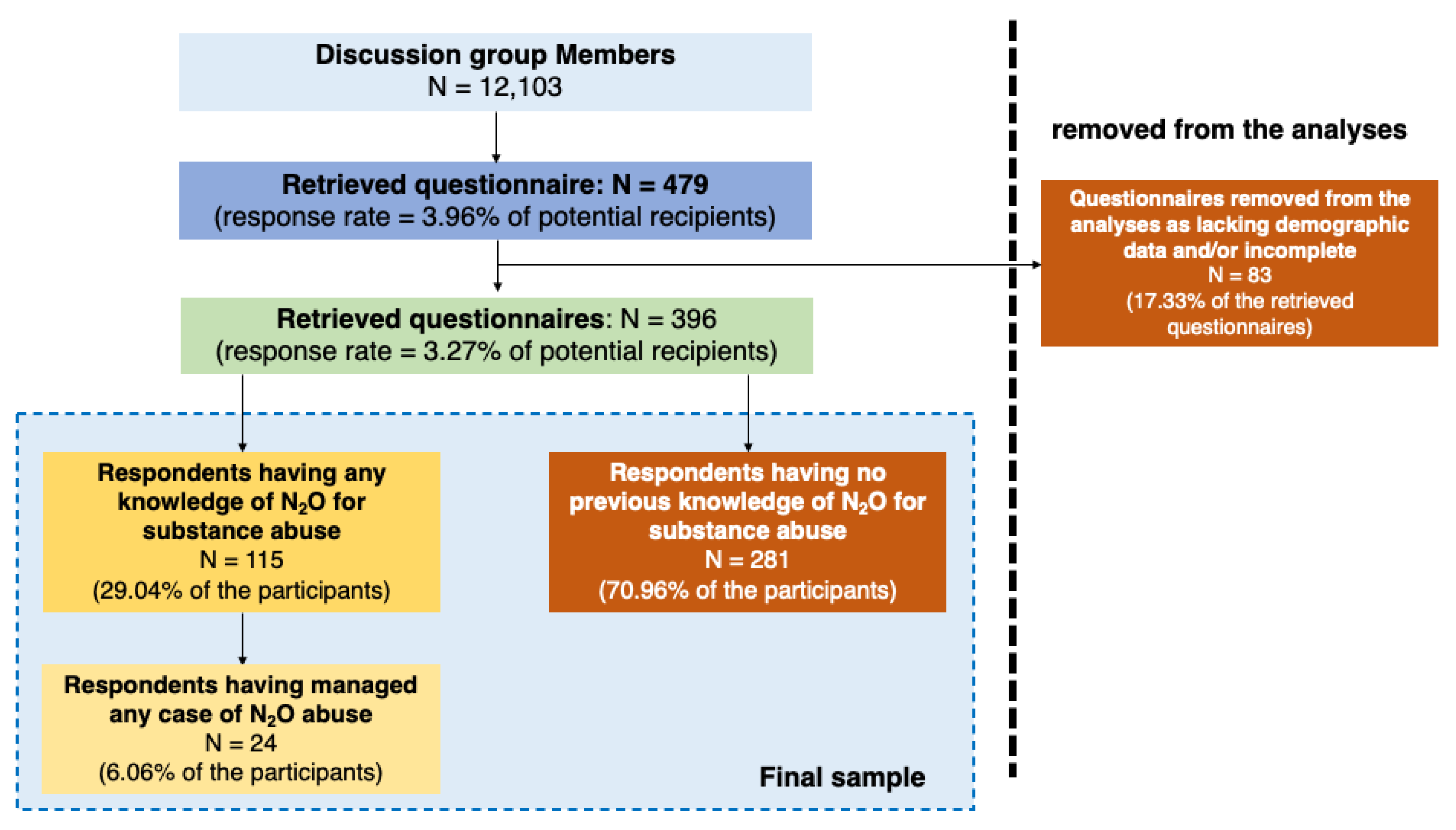

| Participants | 13 | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study, e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed. | 6 |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage. | 6 | ||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram. | 6 | ||

| Descriptive data | 14 | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, and social) and information on exposures and potential confounders. | 6–7 |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | 6–7 | ||

| Outcome data | 15 | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures. | 8–10 |

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included. | 10–13 |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized. | 10–13 | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period. | - | ||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses performed, e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions and sensitivity analyses. | 10–13, Appendix A Table A7, Appendix A Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 |

| Discussion | |||

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives. | 13–15 |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias. | 15–16 |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence. | 13–16 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results. | 13–14 |

| Other information | |||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based. | 17 |

| Informed Consent. Estimated colleague, the present survey has been developed and shared with the aim to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of medical professionals on the N2O abuse in Italy. Alongside vaccination practice, preventive practices against tick bites will also be inquired about. The present survey has only scientific aims. No economic or similar compensation is guaranteed to the participants. |

| While we thank you for your cooperation, we stress that web-based surveys must fulfill the requirements represented by the “Helsinki protocol” and EU Regulation 2016/679. In order to fulfill the requirements of the Helsinki protocol, we are formally requesting your consent. Without your consent, the survey will not continue. Even after your consent, you can leave the present survey at any moment, until the sharing of the questionnaire (button “share module” at the end of the questionnaire). Moreover, we stress that the questionnaire will be registered in anonymous form, and in no way could it be associated with the compiler, as we will not retain any specific, individual information (e.g., signature, personal address, etc.). All requested personal data are generic ones and functional to the demographic analyses (gender, age, etc.). |

According to the EU Regulation 2016/279 (GDPR), we also state the following:

|

Appendix A.1. Authors’ Translation of the Questionnaire

| Yes | No | Do Not Remember/I Prefer Not to Answer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q01. Do you know that N2O can be used as a recreational drug? | [ ] (go to Q02) | [ ] (go to Appendix A.2) | [ ] (go to Appendix A.2) |

| Q02. During your medical practice, did you manage any case of N2O abuse? | [ ] | [ ] | [ ] |

| Q03. During your studies, did you receive any University-level formation on N2O? | [ ] | [ ] | [ ] |

| Your Answer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Since 2010, several countries have experienced an increasing prevalence of N2O abuse. | True | False | Do not know |

| D2. N2O abuse is usually identified through urinary biomarkers. | True | False | Do not know |

| D3. The number of reported N2O poisonings in countries such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom has increased more than 10 times in the last 10 years. | True | False | Do not know |

| D4. Abuse of N2O through use of cartridges and canisters can cause lung barotrauma. | True | False | Do not know |

| D5. Inhalation of N2O can be associated with frost bite of the respiratory airways, mouth, and lips. | True | False | Do not know |

| D6. Upon inhalation, N2O has a latency of around 10 min. | True | False | Do not know |

| D7. Chronic side effects are usually severe and long-lasting. | True | False | Do not know |

| D8. Abuse of N2O does impair the body balance and driving ability. | True | False | Do not know |

| D9. Lung barotrauma is the main cause of death following abuse of N2O. | True | False | Do not know |

| D10. N2O irreversibly inactivates vitamin B12. | True | False | Do not know |

| D11. N2O causes sedation. | True | False | Do not know |

| D12. In cases of chronic toxicity from N2O abuse, most patients complain of sensorimotor symptoms. | True | False | Do not know |

| D13. Chronic N2O abuse is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. | True | False | Do not know |

| D14. Complications associated with chronic N2O abuse are at least partially reversible through a prompt diagnosis. | True | False | Do not know |

| D15. Recreational abuse of N2O is more frequently reported among individuals aged > 25 years than among 15- to 24 year-old subjects. | True | False | Do not know |

| D16. In the last decades, the recreational abuse of N2O among high school students from Northern European countries and France had a lifetime prevalence ranging between… | 1% to 5% 6% to 15% 16% to 25% 26% to 35% Do not know | ||

| D17. Chronic abuse of N2O is frequently associated with magnetic resonance imaging anomalies of the… | Cerebral cortex Brainstem Spinal cord, cervical tract Spinal cord, thoracic tract Do not know | ||

| D18. Symptoms associated with chronic abuse of N2O can be enhanced by… | Surgery of the esophagus Surgery of the stomach and biliary system Surgery of liver and pancreas Surgery of small bowel and large bowel | ||

| D19. Symptoms associated with chronic abuse of N2O can be enhanced by pregnancy. | True | False | Do Not know |

| D20. Paresthesia associated with chronic N2O abuse is usually described as… | Distal (“sock”) Proximal (“glove”) Glove and sock, bilateral and symmetrical Glove and sock, unilateral and/or asymmetrical | ||

| Q04. According to your current understanding, how do you perceive N2O abuse in Italy: | |

| Regarding its SEVERITY | (1) Not significant at all (2) (3) (4) (5) very significant |

| Regarding its FREQUENCY | (1) Not significant at all (2) (3) (4) (5) very significant |

| Q05. How would you rate the health threat represented by | |

| N2O abuse | Not significant at all (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Very Significant |

| Cocaine abuse | Not significant at all (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Very Significant |

| Opioid abuse | Not significant at all (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Very Significant |

| Cannabinoid abuse | Not significant at all (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Very Significant |

| Amphetamine abuse | Not significant at all (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Very Significant |

| Q06. From your point of view, in the following 12 months, N2O abuse | |

| (1) …will be a likely occurrence during daily activities. | |

| Totally disagree | [ ] |

| Disagree | [ ] |

| Neutral | [ ] |

| Agree | [ ] |

| Totally agree | [ ] |

| (2) …will significantly affect your daily activities. | |

| Totally disagree | [ ] |

| Disagree | [ ] |

| Neutral | [ ] |

| Agree | [ ] |

| Totally agree | [ ] |

| Q07. Are you confident of being able to recognize incident N2O abuse cases during your daily activities? | |

| Totally disagree | [ ] |

| Disagree | [ ] |

| Neutral | [ ] |

| Agree | [ ] |

| Totally agree | [ ] |

Appendix A.2. Some Personal Information about You

- A01. Your age: _________ (years)

- A02. Your seniority as a physician: __________ (years)

- A03. Gender: M [ ] F [ ]; Prefer not to answer [ ]

- A04. Region of residence:

| [ ] Northern Italy | Aosta Valley, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy, Veneto, Autonomous Province of Trento, Autonomous Province of Bolzano, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Emilia Romagna |

| [ ] Central Italy | Tuscany, Umbria, Marche, Lazio |

| [ ] Southern Italy | Campania, Abruzzo, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria |

| [ ] Major islands | Sicily, Sardinia |

- A05. At the moment, you are employed as:

- [ ] General practitioner

- [ ] Other medical specialty (internal medicine)

- [ ] Other medical specialty (neurology)

- [ ] Other medical specialty (emergency medicine)

- [ ] Other medical specialty (psychiatry)

- [ ] Other medical specialty

- A06. Your main information source(s) on medical topics:

- [ ] Formation courses

- [ ] Official websites (governmental ones, health authorities, etc.)

- [ ] Non-official websites (blogs, personal websites, etc.)

- [ ] Medical journals

- [ ] Friends, relatives

- [ ] Other healthcare workers

- [ ] Social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.)

| The actual price per liter of nitrous oxide usually ranges between… | EUR 1.15 to 1.15 EUR 0.50 to 1.15 EUR 0.05 to 0.15 EUR 0.05 to 0.01 Do not know | ||

| Heavy users of nitrous oxide report the consumption of around 50 or more balloons in a single session or use from a cylinder. | True | False | Do not know |

| Abuse of nitrous oxide has been associated with mass gathering events such as concerts and rave parties. | True | False | Do not know |

| Nitrous Oxide causes endorphins to be released in certain brain regions. | True | False | Do not know |

| Nitrous oxide is a weak greenhouse gas around 300 times less potent than carbon dioxide. | True | False | Do not know |

| Inhalation of five balloons of nitrous oxide could be acknowledged as equivalent to approximately 7 min of nitrous oxide anesthesia. | True | False | Do not know |

| The clandestine or home production of nitrous oxide is less expensive than that commercially available. | True | False | Do not know |

Appendix A.3. Supplementary Analyses

| Statement | Answer | No./165, % | Correlation with Higher GKS (rho) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Since 2010, several countries have experienced an increasing prevalence of N2O abuse. | TRUE | 92, 80.0% | 0.114 |

| D2. N2O abuse is usually identified through urinary biomarkers. | FALSE | 33, 28.7% | 0.465 (+) |

| D3. The number of reported N2O poisonings in countries such as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom has increased more than 10 times in the last 10 years. | TRUE | 77, 67.0% | 0.422 (+) |

| D4. Abuse of N2O through use of cartridges and canisters can cause lung barotrauma. | TRUE | 71, 61.7% | −0.012 |

| D5. Inhalation of N2O can be associated with frost bite of the respiratory airways, mouth, and lips. | TRUE | 77, 67.0% | 0.270 |

| D6. Upon inhalation, N2O has a latency of around 10 min. | FALSE | 39, 33.9% | 0.447 (+) |

| D7. Chronic side effects are usually severe and long-lasting. | FALSE | 33, 28.7% | 0.348 (+) |

| D8. Abuse of N2O does impair the body balance and driving ability. | FALSE | 93, 80.9% | 0.394 (+) |

| D9. Lung barotrauma is the main cause of death following abuse of N2O. | FALSE | 24, 20.9% | 0.258 |

| D10. N2O irreversibly inactivates vitamin B12. | TRUE | 35, 30.4% | 0.525 (+) |

| D11. N2O causes sedation. | FALSE | 39, 33.9% | 0.489 (+) |

| D12. In cases of chronic toxicity from N2O abuse, most patients complain of sensorimotor symptoms. | TRUE | 95, 82.6% | 0.609 (+) |

| D13. Chronic N2O abuse is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. | TRUE | 63, 54.8% | 0.389 (+) |

| D14. Complications associated with chronic N2O abuse are at least partially reversible through a prompt diagnosis. | TRUE | 69, 60.0% | 0.519 (+) |

| D15. Recreational abuse of N2O is more frequently reported among individuals aged > 25 years than among 15- to 24 year-old subjects. | FALSE | 50, 43.5% | 0.717 (+) |

| D16. In the last decades, the recreational abuse of N2O among high school students from Northern European countries and France had a lifetime prevalence ranging between… | 6% and 15% | 44, 38.3% | 0.598 (+) |

| D17. Chronic abuse of N2O is frequently associated with magnetic resonance imaging anomalies of the… | Spinal cord, cervical tract | 26, 22.6% | 0.701 (+) |

| D18. Symptoms associated with chronic abuse of N2O can be enhanced by… | Surgery of the stomach and biliary system | 17, 14.8% | 0.600 (+) |

| D19. Symptoms associated with chronic abuse of N2O can be enhanced by pregnancy. | TRUE | 69, 60.0% | 0.562 (+) |

| D20. Paresthesia associated with chronic N2O abuse is usually described as… | Glove and sock, bilateral and symmetrical | 40, 34.8% | 0.263 |

References

- Marsden, P.; Sharma, A.A.; Rotella, J.A. Review Article: Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes of Chronic Nitrous Oxide Misuse: A Systematic Review. EMA Emerg. Med. Australas. 2022, 34, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garakani, A.; Jaffe, R.J.; Savla, D.; Welch, A.K.; Protin, C.A.; Bryson, E.O.; McDowell, D.M. Neurologic, Psychiatric, and Other Medical Manifestations of Nitrous Oxide Abuse: A Systematic Review of the Case Literature. Am. J. Addict. 2016, 25, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.C.; Wijnhoven, A.M.; Maessen, G.C.; Blankensteijn, S.R.; van der Heyden, M.A.G. Does Vitamin B12 Deficiency Explain Psychiatric Symptoms in Recreational Nitrous Oxide Users? A Narrative Review. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 59, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Chou, C.C.; Kong, S.S.; Hung, P.C.; Tsai, H.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, J.J.; Chou, I.J.; Lin, K.L. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse Related Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord in Adolescents—A Case Series and Literature Review. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonev, V.; Wyatt, M.; Barton, M.J.; Leitch, M.A. Severe Length-dependent Peripheral Polyneuropathy in a Patient with Subacute Combined Spinal Cord Degeneration Secondary to Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse: A Case Report and Literature Review. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumnall, H. Recreational Use of Nitrous Oxide. BMJ 2022, 378, o2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines, 21st List; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Abuse. Recreational Use of Nitrous Oxide: A Growing Concern for Europe; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Abuse: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Li, S.; Xue, Y.; Yan, P.; Chen, M.; Wu, J. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Prevalence, Neurotoxicity, and Treatment. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, E.B.; Evans, M.R. Nangs, Balloons, and Crackers. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Neurotoxicity. AJGP 2021, 50, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). Drug Misuse in England and Wales: Year Ending June 2022; Office for National Statistics (ONS): London, UK, 2022.

- Chevaliercurt, M.J.; Grzych, G.; Tard, C.; Lannoy, J.; Deheul, S.; Hanafi, R.; Douillard, C.; Vamecq, J.; Grzych, G.; Tard, C.; et al. Nitrous Oxide Abuse in the Emergency Practice, and Review of Toxicity Mechanisms and Potential Markers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 162, 112894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjongjit, A.; Sutamnartpong, P.; Mahanupap, P.; Phanachet, P.; Thanakitcharu, S. Nitrous Oxide-Induced Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Case Report, Potential Mechanisms, and Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluyts, Y.; Vanherpe, P.; Amir, R.; Vanhoenacker, F.; Vermeersch, P. Vitamin B12 Deficiency in the Setting of Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Options in Patients Presenting with Subacute Neurological Complications. Acta Clin. Belg. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Med. 2022, 77, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, J.; Weng, H.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Chang, T.S.; Sung, J.Y.; Lin, C.S.Y. Elucidating Unique Axonal Dysfunction between Nitrous Oxide Abuse and Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porruvecchio, E.; Shrestha, S.; Khuu, B.; Rana, U.I.; Zafar, M.; Zafar, M.; Kiani, A.; Hadid, A. Functional Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Association With Nitrous Oxide Inhalation. Cureus 2022, 14, e21394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, M.; Athiraman, H. Whippets Causing Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Cureus 2022, 14, e23148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edigin, E.; Ajiboye, O.; Nathani, A. Nitrous Oxide-Induced B12 Deficiency Presenting With Myeloneuropathy. Cureus 2019, 11, e5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, J.; Qadri, S.F. Myelopathy Secondary to Vitamin B12 Deficiency Induced by Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Cureus 2021, 13, e18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulkadi, S.; Peters, B.; Vliegen, A.S. Thromboembolic Complications of Recreational Nitrous Oxide (Ab)Use: A Systematic Review. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2022, 54, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Uil, S.H.; Vermeulen, E.G.J.; Metz, R.; Rijbroek, A.; de Vries, M. Aortic Arch Thrombus Caused by Nitrous Oxide Abuse. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2018, 4, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, D.N.; Patterson, K.C.; Quin, K. Venous Thrombosis after Nitrous Oxide Abuse, a Case Report. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 49, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbrock, S.E.; Fokkema, T.M.; Leijdekkers, V.J.; Vahl, A.C.; Konings, R.; van Nieuwenhuizen, R.C. Nitrous Oxide Abuse Associated with Severe Thromboembolic Complications. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 62, 656–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yu, M.; Zheng, D.; Gao, H.; Li, W.; Ma, Y. Electrophysiologic Characteristics of Nitrous-Oxide-Associated Peripheral Neuropathy: A Retrospective Study of 76 Patients. J. Clin. Neurol. 2023, 19, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, X.T.; Nguyen, T.X.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Ha, H.T. Nitrous Oxide-Induced Neuropathy among Recreational Users in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Duan, X.; Dong, M.; Sun, S.; Zhang, P.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, R. Clinical Feature and Sural Biopsy Study in Nitrous Oxide-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollhardt, R.; Mazoyer, J.; Bernardaud, L.; Haddad, A.; Jaubert, P.; Coman, I.; Manceau, P.; Mongin, M.; Degos, B. Neurological Consequences of Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, R.; Parent, T. Peripheral Polyneuropathy and Acute Psychosis from Chronic Nitrous Oxide Poisoning: A Case Report with Literature Review. Medicine 2022, 101, E28611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Ba, F.; Wang, R.; Zheng, D. Imaging Appearance of Myelopathy Secondary to Nitrous Oxide Abuse: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Int. J. Neurosci. 2019, 129, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, A.J.H.P.; Hunault, C.C.; van den Hengel-Koot, I.S.; Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen, J.J.; de Lange, D.W.; Hondebrink, L. Alarming Increase in Poisonings from Recreational Nitrous Oxide Use after a Change in EU-Legislation, Inquiries to the Dutch Poisons Information Center. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 100, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, M.A.; Kresak, J.L.; Falchook, A.; Harris, N.S. Nitrous Oxide Abuse and Vitamin B12 Action in a 20-Year-Old Woman: A Case Report. Lab. Med. 2015, 46, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.T.; Hung, C.T.; Wang, W.M.; Lee, J.T.; Yang, F.C. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse-Induced Vitamin B12 Deficiency in a Patient Presenting with Hyperpigmentation of the Skin. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2013, 5, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, J.; Qureshi, S. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse Causing B12 Deficiency with Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord: A Case Report. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, J.; Xu, R.; Feng, F.; Kan, W.; Ding, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, S.; et al. Clinical Epidemiological Characteristics of Nitrous Oxide Abusers: A Single-Center Experience in a Hospital in China. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inquimbert, C.; Maitre, Y.; Moulis, E.; Gremillet, V.; Tramini, P.; Valcarcel, J.; Carayon, D. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Use and Associated Factors among Health Profession Students in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufayet, L.; Caré, W.; Laborde-Casterot, H.; Chouachi, L.; Langrand, J.; Vodovar, D. Possible Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Recreational Use of Nitrous Oxide in the Paris Area, France. Rev. Med. Interne 2022, 43, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.; Duroy, D.; Perozziello, A.; Sasportes, A.; Lejoyeux, M.; Geoffroy, P.A. A Cross-Sectional Study: Nitrous Oxide Abuse in Parisian Medical Students. Am. J. Addict. 2023, 32, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehirim, E.M.; Naughton, D.P.; Petróczi, A. No Laughing Matter: Presence, Consumption Trends, Drug Awareness, and Perceptions of “Hippy Crack” (Nitrous Oxide) among Young Adults in England. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (StroBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, E.; Schino, S.; Gambadoro, N.; Ricciardi, L.; Trio, O.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Sangiorgi, G. Facing the Pandemic with a Smile: The Case of Memedical and Its Impact on Cardiovascular Professionals. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2022, 71, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Zaniboni, A.; Satta, E.; Ranzieri, S.; Cerviere, M.P.; Marchesi, F.; Peruzzi, S. West Nile Virus Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study on Italian Medical Professionals during Summer Season 2022. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Camisa, V.; Satta, E.; Zaniboni, A.; Ranzieri, S.; Baldassarre, A.; Zaffina, S.; Marchesi, F. When a Neglected Tropical Disease Goes Global: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Italian Physicians towards Monkeypox, Preliminary Results. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Camisa, V.; Di Palma, P.; Minutolo, G.; Ranzieri, S.; Zaffina, S.; Baldassarre, A.; Restivo, V. Managing of Migraine in the Workplaces: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians. Medicina 2022, 58, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Gualerzi, G.; Ranzieri, S.; Ferraro, P.; Bragazzi, N.L. Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices (KAP) of Italian Occupational Physicians towards Tick Borne Encephalitis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingg, A.; Siegrist, M. Measuring People’s Knowledge about Vaccination: Developing a One-Dimensional Scale. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3771–3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C.; Wicker, S. Personal Attitudes and Misconceptions, Not Official Recommendations Guide Occupational Physicians’ Vaccination Decisions. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4478–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, C.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Health Belief Model Variables in Predicting Behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Lau, J.T.F. Influenza Vaccination Uptake and Associated Factors among Elderly Population in Hong Kong: The Application of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imorde, L.; Möltner, A.; Runschke, M.; Weberschock, T.; Rüttermann, S.; Gerhardt-Szép, S. Adaptation and Validation of the Berlin Questionnaire of Competence in Evidence-Based Dentistry for Dental Students: A Pilot Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Ranzieri, S.; Boldini, G.; Zanella, I.; Marchesi, F. Legionnaires’ Disease in Occupational Settings: A Cross-Sectional Study from Northeastern Italy (2019). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, G.; Maio, G.R. 6 Attitudes: Content, Structure and Functions. In An Introduction to Social Psychology; Hewstone, M., Stroebe, W., Jonas, K., Eds.; BPS Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Arghittu, A.; Dettori, M.; Azara, A.; Gentili, D.; Serra, A.; Contu, B.; Castiglia, P. Flu Vaccination Attitudes, Behaviours, and Knowledge among Health Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union; European Council; European Parliament. Europea Union (EU) Regulation N. 2016/679 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation); European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Perino, J.; Tournier, M.; Mathieu, C.; Letinier, L.; Peyré, A.; Perret, G.; Pereira, E.; Fourrier-Réglat, A.; Pollet, C.; Fatseas, M.; et al. Psychoactive Substance Use among Students: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.; Farahmand, P.; Wolkin, A. Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Use Disorder Preceding Symptoms Concerning for Primary Psychotic Illness. Am. J. Addict. 2020, 29, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hew, A.; Lai, E.; Radford, E. Nitrous Oxide Abuse Presenting with Acute Psychosis and Peripheral Neuropathy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, N.; Wakakuri, H.; Uehara, K.; Hyodo, H.; Ohara, T.; Yasutake, M. A Case of Fever, Impaired Consciousness, and Psychosis Caused by Nitrous Oxide Abuse and Misdiagnosed as Acute Meningitis. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2022. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Han, J.; Yu, A.; Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Neurological and Psychological Characteristics of Young Nitrous Oxide Abusers and Its Underlying Causes During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 854977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaar, S.J.; Ferris, J.; Waldron, J.; Devaney, M.; Ramsey, J.; Winstock, A.R. Up: The Rise of Nitrous Oxide Abuse. An International Survey of Contemporary Nitrous Oxide Use. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizink, A.C. Trends and Associated Risks in Adolescent Substance Use: E-Cigarette Use and Nitrous Oxide Use. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.; Nelson, G.; Vu, T.; Judge, B. No Laughing Matter—Myeloneuropathy Due to Heavy Chronic Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 46, 799.e1–799.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liao, J.P.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.F. Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis Caused by Nitrous Oxide Abuse: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 4057–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Bu, B. Isolated Cortical Vein Thrombosis after Nitrous Oxide Use in a Young Woman: A Case Report. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, K.; Lang, H.; He, L.; Chen, N. Nitrous Oxide Inhalation-Induced Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis in a 20-Year-Old Man: A Case Report. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, O.B.; Hvas, A.M.; Grove, E.L. A 19-Year-Old Man with a History of Recreational Inhalation of Nitrous Oxide with Severe Peripheral Neuropathy and Central Pulmonary Embolism. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e931936-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.F.; Al Saud, A.A.; Al Mulhim, A.A.; Liteplo, A.S.; Shokoohi, H. Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse and Massive Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1549.e1–1549.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parein, G.; Bollens, B. Nitrous Oxide-Induced Polyneuropathy, Pancytopenia and Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2023, 17, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Valck, L.; Defelippe, V.M.; Bouwman, N.A.M.G. Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis: A Complication of Nitrous Oxide Abuse. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e244478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, W.; Pariente, A.; Mijahed, R. Extensive Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Secondary to Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 51, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S.; Fan, I.-W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Su, Y.-J. A Nitrous Oxide Abuser Presenting with Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Case Report. Med. Int. 2022, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Beecher, G.; Van DIjk, R.; Hussain, M.; Siddiqi, Z.; Ba, F. Subacute Combined Degeneration from Nitrous Oxide Abuse in a Patient with Pernicious Anemia. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 45, 334–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einsiedler, M.; Voulleminot, P.; Demuth, S.; Kalaaji, P.; Bogdan, T.; Gauer, L.; Reschwein, C.; Nadaj-Pakleza, A.; de Sèze, J.; Kremer, L.; et al. A Rise in Cases of Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Neurological Complications and Biological Findings. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, T.J.; Bascoy, S.; Altaf, M.D.; Surampudy, A.; Chaudhry, B. Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Spinal Cord: A Consequence of Recreational Nitrous Oxide Use. Cureus 2022, 14, e31936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, D.J.T.; Gaillard, F. Pernicious Azotaemia? A Case Series of Subacute Combined Degeneration of the Cord Secondary to Nitrous Oxide Abuse. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 72, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, D.; Agrawal, A.; Gupta, S.; Bajaj, S. Recreational Nitrous Oxide Abuse Causing Ischemic Stroke in a Young Patient: A Rare Case Report. Cureus 2018, 10, e3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berling, E.; Fargeot, G.; Aure, K.; Tran, T.H.; Kubis, N.; Lozeron, P.; Zanin, A. Nitrous Oxide-Induced Predominantly Motor Neuropathies: A Follow-up Study. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 2720–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Li, W.; Gao, H.; Ma, Y.; Dong, X.; Zheng, D. Skin Hyperpigmentation: A Rare Presenting Symptom of Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Clin. Toxicol. 2020, 58, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Qiao, Y.; Li, W.; Fang, X.; Gao, H.; Zheng, D.; Ma, Y. Analysis of Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Factors in 110 Patients with Nitrous Oxide Abuse. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, C.; Zane Horowitz, B. Nitrous Oxide Abuse Induced Subacute Combined Degeneration despite Patient Initiated B12 Supplementation. Clin. Toxicol. 2022, 60, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, M.B.; Samsa, G.P.; Lipton, R.B.; Matchar, D.B. Changing Physician Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs about Migraine: Evaluation of a New Educational Intervention. Headache 2006, 46, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prinzio, R.R.; Nigri, A.G.; Zaffina, S. Total Worker Heath Strategies in Italy: New Challenges and Opportunities for Occupational Health and Safety Practice. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Remoundou, K.; Brennan, M.; Sacchettini, G.; Panzone, L.; Butler-Ellis, M.C.; Capri, E.; Charistou, A.; Chaideftou, E.; Gerritsen-Ebben, M.G.; Machera, K.; et al. Perceptions of Pesticides Exposure Risks by Operators, Workers, Residents and Bystanders in Greece, Italy and the UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F.; Ranzieri, S. Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines 2021, 9, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccardi, M.; Anselmino, M.; Del Greco, M.; Mascia, G.; Paoletti Perini, A.; Mascia, P.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Picano, E. Radiation Awareness in an Italian Multispecialist Sample Assessed with a Web-Based Survey. Acta Cardiol. 2021, 76, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiervang, E.; Goodman, R. Advantages and Limitations of Web-Based Surveys: Evidence from a Child Mental Health Survey. Soc. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noale, M.; Trevisan, C.; Maggi, S.; Incalzi, R.A.; Pedone, C.; Di Bari, M.; Adorni, F.; Jesuthasan, N.; Sojic, A.; Galli, M.; et al. The Association between Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccinations and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Data from the EPICOVID19 Web-Based Survey. Vaccines 2020, 8, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Cattani, S.; Casagranda, F.; Gualerzi, G.; Signorelli, C. Knowledge, Attitudes, Beliefs and Practices of Occupational Physicians towards Vaccinations of Health Care Workers: A Cross Sectional Pilot Study in North-Eastern Italy. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2017, 30, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Zaniboni, A.; Satta, E.; Baldassarre, A.; Cerviere, M.P.; Marchesi, F.; Peruzzi, S. Management and Prevention of Traveler’s Diarrhea: A Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Italian Occupational Physicians (2019 and 2022). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumello, C.; Bramanti, S.M.; Ballarotto, G.; Candelori, C.; Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Crudele, M.; Lombardi, L.; Pignataro, S.; Viceconti, M.L.; et al. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicarelli, G.; Pavolini, E. Health Workforce Governance in Italy. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Vezzosi, L.; Balzarini, F. Challenges Faced by the Italian Medical Workforce. Lancet 2020, 395, e55–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.; Saunders, I. Current Perceptions of Travelers’ Diarrhea Treatments and Vaccines: Results from a Postal Questionnaire Survey and Physician Interviews. J. Travel Med. 2007, 14, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wilcox, C.R.; Calvert, A.; Metz, J.; Kilich, E.; Macleod, R.; Beadon, K.; Heath, P.T.; Khalil, A.; Finn, A.; Snape, M.D.; et al. Attitudes of Pregnant Women and Healthcare Professionals Toward Clinical Trials and Routine Implementation of Antenatal Vaccination Against Respiratory Syncytial Virus: A Multicenter Questionnaire Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S. Interpreting Cross-Sectional Data on Stages of Change. Psychol. Health 2000, 15, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, S.; Higuchi, S. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Epidemiological Studies of Internet Gaming Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 71, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostrud, L.; Thelen, J.; Palatnik, A. Models of Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Non-Pregnant and Pregnant Population: Review of Current Literature. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2022, 18, 2138047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond Confidence: Development of a Measure Assessing the 5C Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Peruzzi, S. Tetanus Vaccination Status and Vaccine Hesitancy in Amateur Basketball Players (Italy, 2020). Vaccines 2022, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipschitz, J.M.; Fernandez, A.C.; Elsa Larson, H.; Blaney, C.L.; Meier, K.S.; Redding, C.A.; Prochaska, J.O.; Paiva, A.L. Validation of Decisional Balance and Self-Efficacy Measures for HPV Vaccination in College Women. Am. J. Health Promot. 2013, 27, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Claas, S.A. Introduction to Epidemiology. In Clinical and Translational Science: Principles of Human Research, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 53–69. ISBN 9780128021019. [Google Scholar]

- di Girolamo, N.; Mans, C. Research Study Design. In Miller—Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 9, pp. 59–62. ISBN 9780323552288. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch, C.; Wicker, S. E-Health Use, Vaccination Knowledge and Perception of Own Risk: Drivers of Vaccination Uptake in Medical Students. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kow, R.Y.; Mohamad Rafiai, N.; Ahmad Alwi, A.A.; Low, C.L.; Ahmad, M.W.; Zakaria, Z.; Zulkifly, A.H. COVID-19 Infodemiology: Association Between Google Search and Vaccination in Malaysian Population. Cureus 2022, 14, e29515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L. Infodemiology and Infoveillance of Multiple Sclerosis in Italy. Mult. Scler. Int. 2013, 2013, 924029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaffi, J.; Meliconi, R.; Landini, M.P.; Mancarella, L.; Brusi, V.; Faldini, C.; Ursini, F. Seasonality of Back Pain in Italy: An Infodemiology Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Baldassarre, A.; Provenzano, S.; Corrado, S.; Cerviere, M.P.; Parisi, S.; Marchesi, F.; Bottazzoli, M. Infodemiology of RSV in Italy (2017–2022): An Alternative Option for the Surveillance of Incident Cases in Pediatric Age? Children 2022, 9, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Valente, M.; Marchesi, F. Are Symptoms Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infections Evolving over Time? Infect. Dis. Now 2022, 52, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellin, G.; Comelli, I.; Lippi, G. Is Google Trends a Reliable Tool for Digital Epidemiology? Insights from Different Clinical Settings. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovetta, A. Reliability of Google Trends: Analysis of the Limits and Potential of Web Infoveillance During COVID-19 Pandemic and for Future Research. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2021, 6, 670226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzych, G.; Deheul, S.; Gernez, E.; Davion, J.B.; Dobbelaere, D.; Carton, L.; Kim, I.; Guichard, J.C.; Girot, M.; Humbert, L.; et al. Comparison of Biomarker for Diagnosis of Nitrous Oxide Abuse: Challenge of Cobalamin Metabolic Parameters, a Retrospective Study. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio: Revisiting the Original Methods of Calculation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (N/396, %) | Average ± S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 145, 36.62% | |

| Female | 251, 63.38% | |

| Age (years) | 42.70 ± 9.71 | |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 63, 15.91% | |

| Seniority (years) | 16.10 ± 9.47 | |

| Seniority ≥ 20 years | 115, 29.04% | |

| Medical specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 47, 11.87% | |

| Neurology | 60, 15.15% | |

| Emergency medicine | 31, 7.83% | |

| General practitioner | 71, 17.93% | |

| Psychiatry | 107, 27.02% | |

| Other | 80, 20.20% | |

| Living in … | ||

| Northern Italy 1 | 197, 49.75% | |

| Central Italy 2 | 115, 29.04% | |

| Southern Italy 3 | 54, 13.64% | |

| Major islands 4 | 30, 7.58% | |

| Reporting any knowledge of N2O abuse | 116, 29.04% | |

| Information source | ||

| Formation courses | 332, 83.84% | |

| Official websites | 326, 82.32% | |

| Non-official websites | 55, 13.89% | |

| Medical journals | 143, 36.11% | |

| Other healthcare workers | 225, 56.82% | |

| Social media | 43, 10.86% | |

| Friends and/or relatives | 0, - |

| Variable | Total (N/115, %) |

|---|---|

| Knowledge status | |

| General knowledge score (average ± SD) | 45.33% ± 24.71 |

| Median value | 46.67% |

| General knowledge score > median (46.67%) | 40, 34.78% |

| Risk perception | |

| Acknowledging N2O abuse as a frequent/very frequent condition | 10, 8.70% |

| Acknowledging N2O abuse as a severe/very severe condition | 61, 53.04% |

| Risk perception score (average ± SD) | 33.67% ± 16.32 |

| Median value | 32.00% |

| Risk perception score > median (32.00%) | 51, 44.35% |

|

Perceiving N2O abuse cases as a likely occurrence during daily activity (agree/totally agree) | 19, 16.52% |

|

Perceiving N2O abuse cases as potentially affecting daily working activities (agree/totally agree) | 14, 12.17% |

|

Confident of being able to recognize a N2O abuse cases (agree/totally agree) | 11, 9.56% |

| Having previously managed any N2O abuse case | 24, 20.87% |

| Any information on N2O abuse | 27, 23.48% |

| Variable | Participants by Their Knowledge of N2O Abuse | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Knowledge (N/115) | No Knowledge (N/281) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 55, 47.8% | 90, 32.0% | 0.004 |

| Female | 60, 52.2% | 191, 68.0% | |

| Age (years) | 39.85 ± 7.25 | 43.86 ± 9.66 | 0.001 |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 4, 3.5% | 59, 21.0% | <0.001 |

| Seniority (years) | 13.33 ± 7.68 | 17.24 ± 9.94 | 0.001 |

| Seniority ≥ 20 years | 18, 15.7% | 96, 34.5% | <0.001 |

| Medical specialty | <0.001 | ||

| Internal medicine | 11, 9.6% | 36, 12.8% | |

| Neurology | 29, 25.2% | 31, 11.0% | |

| Emergency medicine | 18, 15.7% | 13, 4.6% | |

| General practitioner | 21, 18.3% | 50, 17.8% | |

| Psychiatry | 13, 11.3% | 94, 33.5% | |

| Other | 23, 20.0% | 57, 20.3% | |

| Living in … | 0.065 | ||

| Northern Italy 1 | 60, 52.2% | 137, 48.8% | |

| Central Italy 2 | 40, 34.8% | 75, 26.7% | |

| Southern Italy 3 | 9, 7.8% | 45, 16.0% | |

| Major islands 4 | 6, 5.2% | 24, 8.5% | |

| Information source | |||

| Formation courses | 101, 87.8% | 231, 82.2% | 0.219 |

| Official websites | 90, 78.3% | 236, 84.0% | 0.226 |

| Non-official websites | 13, 11.3% | 42, 14.9% | 0.429 |

| Medical journals | 41, 35.7% | 102, 36.3% | 0.995 |

| Other healthcare workers | 63, 54.8% | 162, 57.7% | 0.681 |

| Social media | 16, 13.9% | 27, 9.6% | 0.284 |

| GKS (Average ± SD) | p-Value | RPS (Average ± SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 38.18% ± 6.73 | REFERENCE | 32.00% ± 14.31 | REFERENCE |

| Neurology | 50.11% ± 23.54 | 0.003 | 34.33% ± 18.44 | 0.075 |

| Emergency medicine | 51.48% ± 12.27 | 0.001 | 31.71% ± 14.09 | 0.085 |

| General practitioner | 53.33% ± 33.67 | 0.003 | 34.10% ± 10.93 | 0.058 |

| Psychiatry | 18.46% ± 9.87 | 0.006 | 35.08% ± 19.88 | 0.080 |

| Other specialties | 33.91% ± 19.25 | 0.745 | 45.80% ± 25.77 | 0.056 |

| Variable | Previous Personal Experience in the Managing of N2O Abuse Cases | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any (N/24, %) | Never (N/91, %) | ||

| Gender | 0.353 | ||

| Male | 14, 58.3% | 41, 45.1% | |

| Female | 10, 41.7% | 50, 54.9% | |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 0, - | 4, 4.4% | 0.675 |

| Seniority ≥ 20 years | 4, 16.7% | 14, 15.4% | 1.000 |

| Living in… | 0.068 | ||

| Northern Italy 1 | 17, 70.8% | 43, 47.3% | |

| All other regions 2 | 7, 29.2% | 48, 52.7% | |

| Medical specialty | 0.634 | ||

| Internal medicine | 3, 12.5% | 8, 8.8% | |

| Neurology | 3, 12.5% | 26, 28.6% | |

| Emergency medicine | 4, 16.7% | 14, 15.4% | |

| General practitioner | 4, 16.7% | 17, 18.7% | |

| Psychiatry | 4, 16.7% | 9, 9.9% | |

| Other | 6, 25.0% | 17, 18.7% | |

| Higher knowledge status | 10, 41.7% | 30, 33.0% | 0.579 |

| Higher risk perception score | 11, 45.8% | 40, 44.0% | 1.000 |

| Acknowledging N2O abuse as a frequent/very frequent condition | 0, - | 10, 11.0% | 0.196 |

| Acknowledging N2O abuse as a severe/very severe condition | 7, 29.2% | 54, 59.3% | 0.016 |

| Any information on N2O abuse | 7, 29.2% | 20, 22.0% | 0.639 |

|

Perceiving N2O abuse cases as a likely occurrence during daily activity (agree/totally agree) | 4, 16.7% | 15, 16.5% | 1.000 |

|

Perceiving N2O abuse cases as potentially affecting daily working activities (agree/totally agree) | 8, 33.3% | 6, 6.6% | 0.001 |

|

Confident of being able to recognize N2O abuse cases (agree/totally agree) | 4, 16.7% | 7, 7.7% | 0.347 |

| Information source | |||

| Formation courses | 17, 70.8% | 84, 92.3% | 0.012 |

| Official websites | 20, 83.3% | 70, 76.9% | 0.690 |

| Non-official websites | 0, - | 13, 14.3% | 0.109 |

| Medical journals | 11, 45.8% | 30, 33.0% | 0.352 |

| Other healthcare workers | 10, 41.7% | 53, 58.2% | 0.222 |

| Social media | 3, 12.5% | 13, 14.3% | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Corrado, S.; Bottazzoli, M.; Marchesi, F. Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Physicians (2023). Medicina 2023, 59, 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101820

Riccò M, Ferraro P, Corrado S, Bottazzoli M, Marchesi F. Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Physicians (2023). Medicina. 2023; 59(10):1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101820

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiccò, Matteo, Pietro Ferraro, Silvia Corrado, Marco Bottazzoli, and Federico Marchesi. 2023. "Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Physicians (2023)" Medicina 59, no. 10: 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101820

APA StyleRiccò, M., Ferraro, P., Corrado, S., Bottazzoli, M., & Marchesi, F. (2023). Nitrous Oxide Inhalant Abuse: Preliminary Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Physicians (2023). Medicina, 59(10), 1820. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59101820