Abstract

Background and Objectives: An increasing number of studies have shown the influence of primary tumor location of colon cancer on prognosis, but the prognostic difference between colon cancers at different locations remains controversial. After comparing the prognostic differences between left-sided and right-sided colon cancer, the study subdivided left-sided and right-sided colon cancer into three parts, respectively, and explored which parts had the most significant prognostic differences, with the aim to further analyze the prognostic significance of primary locations of colon cancer. Materials and Methods: Clinicopathological data of patients with colon cancer who underwent radical surgery from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program database were analyzed. The data was divided into two groups (2004–2009 and 2010–2015) based on time intervals. Two tumor locations with the most significant survival difference were explored by using Cox regression analyses. The prognostic difference of the two locations was further verified in survival analyses after propensity score matching. Results: Patients with right-sided colon cancer had worse cancer-specific and overall survival compared to left-sided colon cancer. Survival difference between cecum cancer and sigmoid colon cancer was found to be the most significant among six tumor locations in both 2004–2009 and 2010–2015 time periods. After propensity score matching, multivariate analyses showed that cecum cancer was an independent unfavorable factor for cancer specific survival (HR [95% CI]: 1.11 [1.04–1.17], p = 0.001 for 2004–2009; HR [95% CI]: 1.23 [1.13–1.33], p < 0.001 for 2010–2015) and overall survival (HR [95% CI]: 1.09 [1.04–1.14], p < 0.001 for 2004–2009; HR [95% CI]: 1.09 [1.04–1.14], p < 0.001 for 2010–2015) compared to sigmoid colon cancer. Conclusions: The study indicates the prognosis of cecum cancer is worse than that of sigmoid colon. The current dichotomy model (right-sided vs. left-sided colon) may be inappropriate for the study of colon cancer.

1. Introduction

In the era of personalized and precise treatment, due to differences in anatomy and histology between right-sided and left-sided colon, increasing studies have begun to explore whether different primary tumor locations for colon cancer have a significant impact on prognosis [1,2,3,4,5]. Most previous studies have shown that patients with right-sided colon cancer (RCC) have a poorer prognosis compared with left-sided colon cancer (LCC) [1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9], but others are inconsistent [10,11,12,13]. Warschkow et al. found a better survival outcome in RCC relative to LCC among patients with stage I–III colon cancer using the propensity score matched (PSM) method [11]. Therefore, there is still a controversy in survival differences between RCC and LCC.

Up to now, the definition of RCC has been divided because some studies classified the transverse colon as right-sided colon, but others excluded it directly [1,8,9,10,11,13,14]. In addition, it has been found in some studies that transverse colon cancer has different biological characteristics from RCC [15,16,17,18]. Therefore, the conflicting results may be partly due to the inconsistency of location grouping criteria, and the dichotomy model (right-sided vs. left-sided colon) may be inappropriate for the study of colon cancer [16,17,18,19]. Moreover, the prognostic differences between specific subsites (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon) have also been reported in a few studies [19,20,21]. In order to further explore the effects of tumor locations on prognosis, it is essential to find two parts with the greatest survival differences by comparing different primary tumor locations.

In our study, we collected the data of patients with stage I–III colon cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database. By analyzing colon cancer data in the SEER database, it was found that the survival difference between cecum and sigmoid colon cancer was most significant among different locations. Then the prognostic significance of the two locations was further explored in multivariate survival analyses after PSM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

Colon cancer data are from the SEER database. SEER is an authoritative source for cancer statistics, consisting of 18 population-based cancer registries and covering approximately 34.6% of patients with cancer in the United States. Clinicopathological information, including patient demographics, primary tumor location, tumor morphology and stage at diagnosis, treatment course, and follow-up for vital status, was extracted using the “case listing” option of the SEER*Stat 8.3.6 software.

2.2. Study Design

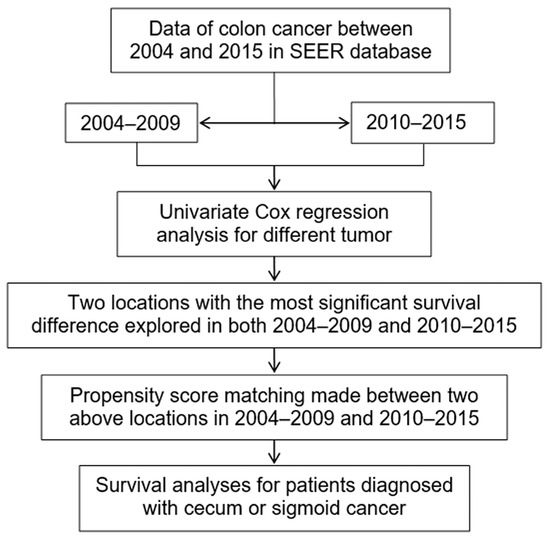

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the whole study design. According to chronological order, data of colon cancer between 2004 and 2015 in SEER were divided into two groups (2004–2009 and 2010–2015) with December 2009 as the cut-off point. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was defined as an endpoint of death from cause relevant with colon cancer. Overall survival (OS) was defined as an endpoint of death from any cause, whichever came first. By using univariate Cox regression analyses in both 2004–2009 and 2010–2015, two tumor locations with the most significant survival difference were explored. Then PSM method was carried out between those two tumor locations in the two groups, respectively. Finally, survival analyses were performed to further validate the prognostic significance of the two tumor locations with the most significant survival difference.

Figure 1.

Research approach for colon cancer. Footnotes: SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

2.3. Patients Selection

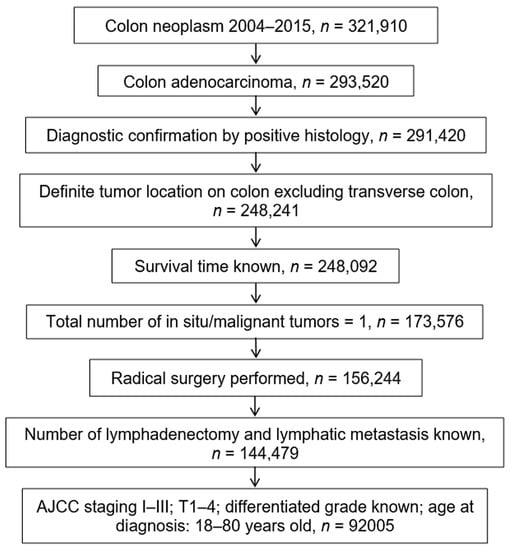

Primary selection criteria for study cases included: (1) diagnosis of colon cancer between 2004 and 2015; (2) histological confirmation of colon adenocarcinoma; (3) definite tumor location on colon, excluding transverse colon (since it is still difficult to strictly define the scope of the right-sided or left-sided colon, it is not appropriate to simply classify transverse colon as which side of the colon); (4) survival time known; (5) suffering from colon cancer only; (6) radical surgery performed; (7) number of lymphadenectomy and lymph node metastasis known; (8) no distant metastasis and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) T1–T4; (9) differentiated grade known; (10) age range: 18–80 years old. A total of 92,005 patients with colon cancer in SEER met our inclusion criteria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Screening flowchart for colon cancer in the SEER database. Footnotes: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; T, primary tumor; SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Frequency distribution of clinicopathological variables was compared with the χ2 test. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards model. The variables with p < 0.1 in the univariate analyses were included in a multivariate proportional hazard regression model. To further minimize biases in baseline characteristics, the PSM method was adopted to balance covariates with statistical differences between cecum and sigmoid colon groups. The patients in the cecum group were then matched as 1:1 with those in the sigmoid colon group by nearest neighbor matching. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to weigh the biases of each variable between the two groups. A caliper was used to define the maximum allowable difference (SMD < 0.1) between two groups to ensure good matches. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 and R software 3.6.3.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinicopathological Features in Total Cohort

A total of 92,005 patients diagnosed with colon cancer between 2004 and 2015 were included in the study. The median follow-up time was 56 months (IQR 27 to 96 months) in overall cohort. At the end of the follow-up period, 66,224 (71.98%) patients were alive, 15,010 (16.31%) died from colon cancer, and 15,010 (11.71%) died due to other reasons. These patients were divided into two groups according to the time of diagnosis. Among all patients, 45,645 (49.6%) patients were diagnosed between 2004 and 2009, and the remaining 46,360 (50.4%) patients were diagnosed between 2010 and 2015 (Table S1).

Univariate regression COX analyses showed that patients with RCC had worse CSS (HR [95%CI]: 1.09 [1.04–1.13] for 2004–2009; HR [95% CI]: 1.20 [1.14–1.27] for 2010–2015) and OS (HR [95%CI]: 1.16 [1.13–1.20] for 2004–2009; HR [95% CI]: 1.22 [1.17–1.28] for 2010–2015) compared to LCC.

In order to further analyze the greatest survival differences between RCC and LCC, we separated right-sided and left-sided cancer into three parts respectively: cecum (2004–2009: 16,313/45,645, 35.7%; 2010–2015: 16,175/46,360, 34.9%), ascending colon (2004–2009: 3308/45,645, 7.2%; 2010–2015: 3568/46,360, 7.7%), hepatic flexure (2004–2009: 1961/45,645, 4.3%; 2010–2015: 1798/46,360, 3.9%), splenic flexure (2004–2009: 2637/45,645, 5.8%; 2010–2015: 2348/46,360, 5.1%), descending colon (2004–2009: 9935/45,645, 21.8%; 2010–2015: 10,941/46,360, 23.6%), and sigmoid colon (2004–2009: 11,491/45,645, 25.2%; 2010–2015: 11,530/46,360, 24.9%) (Table S1).

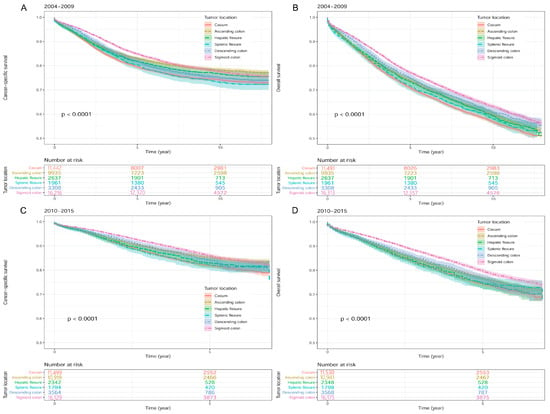

In univariate Cox regression analysis, when sigmoid colon cancer was compared to colon cancer in other locations, we found that CSS difference between patients with cecum cancer and patients with sigmoid colon cancer (HR [95% CI]: 1.24 [1.18–1.30]) was second only to that between splenic flexure colon cancer and sigmoid colon cancer (HR [95% CI]: 1.26 [1.14–1.38]) (Figure 3A), while OS difference between patients with cecum cancer and patients with sigmoid colon cancer (HR [95% CI]: 1.25 [1.21–1.30]) was the most significant in the 2004–2009 group (Figure 3B) (Table 1). In the 2010–2015 group, among six locations, patients with cecum cancer and sigmoid colon cancer had the most remarkable survival difference in both CSS (HR [95% CI]: 1.39 [1.30–1.49]; Figure 3C) and OS (HR [95% CI]: 1.35 [1.28–1.43]; Figure 3D) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to different colon cancer locations in the SEER database. (A) Cancer-specific survival in 2004–2009. (B) Overall survival in 2004–2009. (C) Cancer-specific survival in 2010–2015. (D) Overall survival in 2010–2015. Footnotes: SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 1.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of different tumor locations in patients with colon cancer in the SEER database.

3.2. Clinicopathological Features for Cecum Cancer Compared with Sigmoid Colon Cancer

The demographics and clinicopathological features of patients with cecum cancer versus sigmoid colon cancer are summarized in Table 2. In the 2004–2009 group, the distribution of clinicopathological variables in both tumor locations showed significant difference except for lymph node metastasis (LNM) (p = 0.507). In the 2010–2015 group, all other variables, not including LNM (p = 0.615) and CEA (p = 0.125), presented an obvious imbalance between cecum and sigmoid colon cancer. Patients with cecum cancer were more likely to be older (p < 0.001 for both groups), female (p < 0.001 for both groups), and Caucasian (p < 0.001 for both groups) than those with sigmoid colon cancer. Compared with sigmoid colon cancer, patients with cecum cancer accounted for a larger proportion in poor differentiation (p < 0.001 for both groups), more lymph node dissection (LND) ≥ 12 (p < 0.001 for both groups), late TNM stage (p < 0.001 for both groups), positive CEA value (p = 0.003 for the 2004–2009 group), and more LNM (p = 0.003 for the 2010–2015 group). In addition, fewer patients diagnosed with cecum cancer received radiotherapy (p < 0.001 for both groups) or chemotherapy (p < 0.001 for both groups) in contrast to those with sigmoid colon cancer.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinicopathological data of patients with sigmoid colon cancer versus cecum cancer in the SEER database.

To adjust for these differences in baseline characteristics and minimize biases between both primary cancer locations, a PSM analysis was performed (Table 3). After matching with 1:1 ratio for cecum and sigmoid colon cancer, there were 9926 patients in each tumor location for the 2004–2009 group, and 10,044 patients in each tumor location were included in the final analysis for the 2010–2015 group. Figure S1 showed that matched results are basically consistent with the weighted data (SMD < 0.1).

Table 3.

Comparison of clinicopathological features of patients with sigmoid colon cancer versus cecum cancer after propensity score matching in the SEER database.

3.3. Survival Analyses after PSM for Patients Diagnosed with Cecum or Sigmoid Cancer

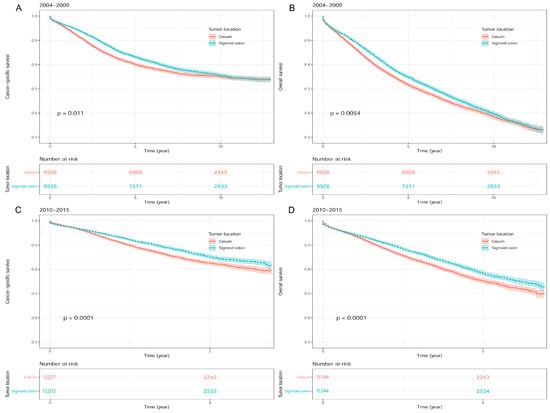

In the univariate Cox regression analyses, a worse survival outcome was found in patients with cecum cancer compared to those with sigmoid colon cancer for both 2004–2009 (HR [95% CI]: 1.08 [1.02–1.14] for CSS; HR [95% CI]: 1.07 [1.02–1.11] for OS) and 2010–2015 groups (HR [95% CI]: 1.23 [1.14–1.33] for CSS; HR [95% CI]: 1.19 [1.12–1.27] for OS) (Figure 4; Table 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves between sigmoid colon cancer and cecum cancer after propensity score matching in SEER database. (A) Cancer-specific survival in 2004–2009. (B) Overall survival in 2004–2009. (C) Cancer-specific survival in 2010–2015. (D) Overall survival in 2010–2015. Footnotes: SEER, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 4.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors after propensity score matching for patients diagnosed with cecum or sigmoid cancer.

Table 5 presents the multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors after PSM. For the 2004–2009 group, the multivariate analyses identified cecum cancer as an independent unfavorable factor of CSS (HR [95% CI]: 1.11 [1.04–1.17]) and OS (HR [95% CI]: 1.09 [1.04–1.14]) relative to sigmoid colon cancer. Similarly, we found that patients with cecum cancer had a worse CSS (HR [95% CI]: 1.23 [1.13–1.33]) and OS (HR [95% CI]: 1.19 [1.11–1.27]) than cecum cancer in the 2010–2015 group.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors after propensity score matching. Variables with p value less than 0.01 in univariate analysis were incorporated into multivariate Cox regression analysis.

4. Discussion

Right-sided and left-sided colons deriving from different embryologic origin are clinically and molecularly distinct. However, the influence of primary tumor locations on the prognosis remains controversial [20,22,23,24,25]. In the present study, we found that patients with RCC had worse CSS and OS than LCC, and the two tumor locations with the greatest survival difference were cecum and sigmoid colon. Moreover, multivariate Cox regression analyses further demonstrated the worse prognosis (CSS and OS) of patients with cecum cancer compared with sigmoid colon cancer after PSM, which is helpful to further explore the influence of primary tumor locations on prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to find that the prognostic difference between cecum and sigmoid colon cancer is the greatest between RCC and LCC, which may partly account for the prognostic difference between RCC and LCC.

Currently, most of previous studies demonstrated a poorer prognosis in RCC versus LCC, which is consistent with the present study [1,2,3,4,6,7]. A large retrospective study presented a lower five-year survival rate for RCC (70.4%) relative to LCC (74.0%) in Japan [1]. And RCC also showed a significantly worse five-year survival (HR [95% CI]: 1.71 [1.10–2.64], p = 0.017) in a retrospective study of patients with colon cancer present in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [14]. By analyzing the prognosis of patients with unresectable colon cancer liver metastasis, Zhao et al. found that the risk of survival deterioration of RCC was significantly higher than that of LCC [26]. A meta-analysis from 66 researches reported that patients with RCC had their risk of death increased by 18% compared to LCC, which was independent of stage [7]. Another recent meta-analysis from 14 studies on metastatic colorectal cancer reported that primary cancer originating from the right-sided colon was significantly related with a worse survival in contrast to left-sided colon [3]. In addition, the present study divided the data into two parts according to the time period so as to reduce the confounding bias caused by the large time span. The difference in the prognosis of patients with RCC and LCC was shown to be consistent in the two time groups, which further confirmed the worse prognosis of RCC over LCC.

As a large sample database with longitudinal data, it is very suitable to utilize the data from the SEER database to analyze the prognostic significance of primary tumor locations. Although there have been several studies about the survival difference between RCC and LCC based on the SEER database, few studies further analyzed the prognostic differences of more precise tumor locations [8,9,10,11,19,27]. The study published by Meguid et al. including 77,978 patients who underwent surgical resection for aggressive colon cancer from 1988 to 2003 in the SEER database showed a 4.2% increased mortality risk associated with RCC versus LCC [8]. Furthermore, the subset analyses stratified by AJCC stage revealed that the higher mortality risk of patients with RCC was observed in stages III and IV compared to patients with LCC [8]. Weiss et al. summarized the data of colon cancer from 1992 to 2005. Although there was no statistical difference in the prognosis between patients with RCC and LCC in the overall cohort, further stratified analysis indicated a higher mortality of patients with RCC compared to LCC in stage III [10]. In order to further explore the prognostic significance between RCC and LCC, Warschkow et al. collected the data of patients with stage I–III colon cancer from the SEER database between 2004 and 2012 and performed a PSM analysis to minimize biases between both primary cancer locations [11]. After PSM, the survival prognosis of patients with RCC was found to be superior to those with LCC regarding OS and CSS in overall cohort, which contradicts our study [11]. However, although Warschkow et al. adopted the PSM, they did not adjust for radiotherapy and chemotherapy in baseline characteristics, which obviously has a great impact on the survival analyses [11]. In addition, our study not only summarized more recent data from 2005 to 2015, but also divided the data into two groups (2004–2009 and 2010–2015) based on time intervals for mutual verification between the two time periods, which reduced the bias due to inconsistent previous treatment standards. Wang et al. also made full use of the data from the SEER database to analyze the survival distinction between RCC and LCC by adopting a competing risk model. The results showed that the cancer-specific mortality (CSM) of RCC significantly increased compared with LCC in the overall cohort [9]. Obviously, not only the inclusion and exclusion criteria of these studies based on the SEER database were inconsistent, but also these grouping criteria according to primary tumor locations were different [8,9,10,11]. Moreover, these studies did not further explore the prognostic differences among more precise tumor locations, especially cecum and sigmoid colon [8,9,10,11].

The present study showed that the survival difference between cecum cancers and sigmoid colon cancers is the largest among the six colon sites, which is akin to the results of Shaib et al. [21]. By analyzing the data of patients with non-metastatic, invasive right-sided adenocarcinoma of the colon from 1988 to 2014 who underwent partial colectomy in SEER, Nasseri at al found that cecum cancers were prone to poorer disease-specific survival (median 86.0, 93.0, and 89.0 months, respectively, p < 0.001) and OS (median not reached, p < 0.001) compared with cancers in other sites of the right colon [19]. In addition, Ben-Aharon et al. also found that the Oncotype Recurrence Score, a clinically validated predictor of recurrence risk in patients with stage II CRC, gradually decreased across the colon (cecum, highest score; sigmoid, lowest score; p = 0.04) [20]. In the present study, patients with cecum cancer had more poorly differentiated tumor, advanced LNM, and late TNM stage compared with sigmoid colon cancer, which is in line with results of previous studies [1,2,9,28]. The prognosis of cecum cancer was worse than sigmoid colon cancer regardless of 2004–2009 or 2010–2015 group in univariate analyses. It is worth noting that the prognostic difference between cecum cancer and sigmoid colon cancer is still significant after PSM. Moreover, after adjusting for differences in clinicopathological characteristics, the multivariate analyses identified cecum cancer as an independent unfavorable factor of CSS and OS relative to sigmoid colon cancer. All in all, our study further confirmed that the location of primary colon cancer was an important prognostic factor and suggested that the prognosis of cecum is worse than that of sigmoid colon cancer.

The reasons might be related to the different embryological origins of colon tissue—proximal colon (right-sided) deriving from mid-gut and distal colon (left-sided) deriving from hind-gut [29]. Meanwhile, different gut microbiota in left and right-sided colon cause differences in colonic mucosal immunology, which theoretically should be the largest between the cecum and the sigmoid colon [30]. From the perspective of clinical symptoms, obstruction and hematochezia due to LCC occurred more frequently than those due to RCC, which is helpful for the early diagnosis and treatment of sigmoid colon cancer [31]. Ward et al. hypothesized three pathways through which tumor site impacts survival differences, including TNM stage, microsatellite instability (MSI), and other genetic drivers [14]. Many previous studies have suggested that the potential molecular mechanism contributing to the different prognosis between RCC and LCC might be associated with differences in gene expression and signaling pathways [14,20,28,32,33,34,35,36]. Some chemotherapy regimens were also found to have different efficacy between LCC and RCC due to different microsatellite status [34]. Anatomically, the difference between cecum and sigmoid colon is the largest, which may suggest that the prognostic difference between cecum and sigmoid colon cancer is also most significant. In addition, the mobility of the sigmoid colon is better than that of the cecum, which helps to improve the curative effect of surgery and survival.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, although this study grouped the cases according to the time interval and analyzed them separately, due to the large time span, it is still difficult to eliminate the influence of inconsistent treatment standards before and after on the study results. Second, a few confounders are not matched perfectly despite adopting PSM method, which may influence the results to some extent. Third, other potential biases from unobserved confounders may be ignored, such as MSI status, socioeconomic status, environmental exposures, and so on.

5. Conclusions

The present study indicates that the prognosis of patients with cecum cancer is worse than those with sigmoid colon cancer, which may partly account for the prognostic difference between RCC and LCC. The dichotomy model (right-sided vs. left-sided colon) may be inappropriate for the study of colon cancer. Tumor locations should be further refined in future research and treatment so as to provide better guidance for individualized treatment of patients with colon cancer. Further studies are very worthy to analyze the potential molecular mechanism and instruct individualized treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/medicina59010045/s1, Figure S1: Comparison of unmatched, matched, and weighted data. (A) 2004–2009. (B) 2010–2015. Table S1: Demographic data for patients with colon cancer in SEER database from 2004 to 2009 and 2010 to 2015.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and W.W.; Methodology, W.W. and D.K.; Software, H.Z. and S.S.; Validation, J.W., D.K. and W.W.; Formal Analysis, S.S. and W.W.; Resources, H.Z. and J.W.; Data Curation, H.Z. and J.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.S., H.Z. and J.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, W.W. and D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not involved any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since our analysis was based on (secondary) data from the SEER database, ethical review and approval were waived for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Since our analysis was based on (secondary) data from the SEER database, patient consent was waived for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute in the United States (http://www.seer.cancer.gov).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Nakagawa-Senda, H.; Hori, M.; Matsuda, T.; Ito, H. Prognostic impact of tumor location in colon cancer: The Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shida, D.; Tanabe, T.; Boku, N.; Takashima, A.; Yoshida, T.; Tsukamoto, S.; Kanemitsu, Y. Prognostic Value of Primary Tumor Sidedness for Unresectable Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holch, J.; Ricard, I.; Stintzing, S.; Modest, D.; Heinemann, V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 70, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, D.; Lueza, B.; Douillard, J.; Peeters, M.; Lenz, H.; Venook, A.; Heinemann, V.; Van Cutsem, E.; Pignon, J.; Tabernero, J.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1713–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraes, L.C.; Steele, S.R.; Valente, M.A.; Lavryk, O.A.; Connelly, T.M.; Kessler, H. Right colon, left colon, and rectal cancer have different oncologic and quality of life outcomes. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunakawa, Y.; Ichikawa, W.; Tsuji, A.; Denda, T.; Segawa, Y.; Negoro, Y.; Shimada, K.; Kochi, M.; Nakamura, M.; Kotaka, M.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Primary Tumor Location on Clinical Outcomes of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated With Cetuximab Plus Oxaliplatin-Based Chemotherapy: A Subgroup Analysis of the JACCRO CC-05/06 Trials. Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, e171–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Tomasello, G.; Borgonovo, K.; Ghidini, M.; Turati, L.; Dallera, P.; Passalacqua, R.; Sgroi, G.; Barni, S. Prognostic Survival Associated With Left-Sided vs Right-Sided Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguid, R.; Slidell, M.; Wolfgang, C.; Chang, D.; Ahuja, N. Is there a difference in survival between right- versus left-sided colon cancers? Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 2388–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wainberg, Z.; Raldow, A.; Lee, P. Differences in Cancer-Specific Mortality of Right- Versus Left-Sided Colon Adenocarcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database Analysis. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2017, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Pfau, P.; O’Connor, E.; King, J.; LoConte, N.; Kennedy, G.; Smith, M. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: Analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results--Medicare data. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4401–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschkow, R.; Sulz, M.; Marti, L.; Tarantino, I.; Schmied, B.; Cerny, T.; Güller, U. Better survival in right-sided versus left-sided stage I–III colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritani, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Okabayashi, K.; Ishii, Y.; Endo, T.; Kitagawa, Y. Difference in the recurrence rate between right- and left-sided colon cancer: A 17-year experience at a single institution. Surg. Today 2014, 44, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hirano, Y.; Ishii, T.; Kondo, H.; Hara, K.; Obara, N.; Yamaguchi, S. Left colon as a novel high-risk factor for postoperative recurrence of stage II colon cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.M.; Cauley, C.E.; Stafford, C.E.; Goldstone, R.N.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Kunitake, H.; Berger, D.L.; Ricciardi, R. Tumour genotypes account for survival differences in right- and left-sided colon cancers. Color. Dis. 2022, 24, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, S.; Deng, G.; Wu, X.; He, J.; Pei, H.; Shen, H.; Zeng, S. A prognostic analysis of 895 cases of stage III colon cancer in different colon subsites. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2015, 30, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mima, K.; Cao, Y.; Chan, A.; Qian, Z.; Nowak, J.; Masugi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Song, M.; da Silva, A.; Gu, M.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in Colorectal Carcinoma Tissue According to Tumor Location. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2016, 7, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loree, J.; Pereira, A.; Lam, M.; Willauer, A.; Raghav, K.; Dasari, A.; Morris, V.; Advani, S.; Menter, D.; Eng, C.; et al. Classifying Colorectal Cancer by Tumor Location Rather than Sidedness Highlights a Continuum in Mutation Profiles and Consensus Molecular Subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Agrawal, R.; Zou, S.; Haseeb, M.A.; Gupta, R. Anatomic location of colorectal cancer presents a new paradigm for its prognosis in African American patients. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseri, Y.; Wai, C.; Zhu, R.; Sutanto, C.; Kasheri, E.; Oka, K.; Cohen, J.; Barnajian, M.; Artinyan, A. The impact of tumor location on long-term survival outcomes in patients with right-sided colon cancer. Tech. Coloproctol. 2022, 26, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Aharon, I.; Goshen-Lago, T.; Sternschuss, M.; Morgenstern, S.; Geva, R.; Beny, A.; Dror, Y.; Steiner, M.; Hubert, A.; Idelevich, E.; et al. Sidedness Matters: Surrogate Biomarkers Prognosticate Colorectal Cancer upon Anatomic Location. Oncologist 2019, 24, e696–e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaib, W.L.; Zakka, K.M.; Jiang, R.; Yan, M.; Alese, O.B.; Akce, M.; Wu, C.; Behera, M.; El-Rayes, B.F. Survival outcome of adjuvant chemotherapy in deficient mismatch repair stage III colon cancer. Cancer 2020, 126, 4136–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missiaglia, E.; Jacobs, B.; D’Ario, G.; Di Narzo, A.; Soneson, C.; Budinska, E.; Popovici, V.; Vecchione, L.; Gerster, S.; Yan, P.; et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, M.; Lochhead, P.; Morikawa, T.; Huttenhower, C.; Chan, A.T.; Giovannucci, E.; Fuchs, C.; Ogino, S. Colorectal cancer: A tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut 2012, 61, 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, M.; Morikawa, T.; Kuchiba, A.; Imamura, Y.; Qian, Z.; Nishihara, R.; Liao, X.; Waldron, L.; Hoshida, Y.; Huttenhower, C.; et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut 2012, 61, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carethers, J. One colon lumen but two organs. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhu, J.; Huang, C.; Yuan, R.; Zhu, Z. Impact of primary tumor resection on the survival of patients with unresectable colon cancer liver metastasis at different colonic subsites: A propensity score matching analysis. Acta Chir. Belg. 2021, 121, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zheng, S.; Chen, C.; Lyu, J. Evaluation and Prediction Analysis of 3- and 5-Year Survival Rates of Patients with Cecal Adenocarcinoma Based on Period Analysis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 7317–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.L.; Lin, C.C.; Jiang, J.K.; Lin, H.H.; Lan, Y.T.; Wang, H.S.; Yang, S.H.; Chen, W.S.; Lin, T.C.; Lin, J.K.; et al. Clinicopathological and molecular differences in colorectal cancer according to location. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2019, 34, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Malietzis, G.; Askari, A.; Bernardo, D.; Al-Hassi, H.; Clark, S. Is right-sided colon cancer different to left-sided colorectal cancer?—A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2015, 41, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Pop, M.; Deboy, R.; Eckburg, P.; Turnbaugh, P.; Samuel, B.; Gordon, J.; Relman, D.; Fraser-Liggett, C.; Nelson, K. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 2006, 312, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mege, D.; Manceau, G.; Beyer, L.; Bridoux, V.; Lakkis, Z.; Venara, A.; Voron, T.; de’Angelis, N.; Abdalla, S.; Sielezneff, I.; et al. Right-sided vs. left-sided obstructing colonic cancer: Results of a multicenter study of the French Surgical Association in 2325 patients and literature review. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinicrope, F.; Mahoney, M.; Yoon, H.; Smyrk, T.; Thibodeau, S.; Goldberg, R.; Nelson, G.; Sargent, D.; Alberts, S. Analysis of Molecular Markers by Anatomic Tumor Site in Stage III Colon Carcinomas from Adjuvant Chemotherapy Trial NCCTG N0147 (Alliance). Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5294–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, Y.; Kim, K.-J.; Han, S.-W.; Rhee, Y.Y.; Bae, J.M.; Wen, X.; Cho, N.-Y.; Lee, D.-W.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, T.-Y.; et al. Adverse prognostic impact of the CpG island methylator phenotype in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbiel, D.; Saridaki, Z.; Roth, A.; Bosman, F.; Delorenzi, M.; Tejpar, S. Prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil or FOLFIRI in relation to microsatellite status: Results of the PETACC-3 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Park, J.; Lim, H.; Kang, W.; Park, Y.; Kim, S. The Impact of Primary Tumor Sidedness on the Effect of Regorafenib in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 1611–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Lin, K.; Chang, T.; Zou, L.; Xing, P.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y. Identification of genomic expression differences between right-sided and left-sided colon cancer based on bioinformatics analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).