1. Introduction

The prevalence and impact of noncommunicable diseases have increased dramatically in the past decades. Among these, diabetes mellitus (DM) has become a challenge for healthcare systems all around the globe with approximately 537 million persons worldwide living with diabetes and with an estimated increase to 783 million individuals by 2045 [

1]. It is also known that the 21st century has witnessed a rise in the prevalence of psychiatric diseases, with significant negative effects on morbidity and on patients’ quality of life, with some of these being frequent comorbidities in patients with DM [

2].

Among mental health conditions, anxiety disorders are common in individuals with DM in such a degree that some authors consider this metabolic disease as a risk factor for anxiety symptoms, while the most frequently encountered types of anxiety in patients with DM are generalised anxiety disorder and social phobia [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Several trials have proven the negative impact of psychiatric diseases on diabetes-related self-care and, subsequently, on glycaemic control and even on the risk of mortality of the affected patients [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This association is of paramount importance since it is already well known that diabetes self-management education and support represents one of the most important aspects of diabetes treatment strategy and that the improvement of self-care behaviours can lead to a reduced risk of chronic degenerative complications, such as microangiopathy, macroangiopathy and neuropathy, acute metabolic complications and to a more favourable evolution of the disease [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Therefore, it becomes evident that for successful, comprehensive and interdisciplinary management of patients with DM it is essential to accurately assess the diabetes-related self-care activities early in all patients with DM and also to determine the presence and severity of additional psychological conditions, including anxiety-related diseases. Several accessible, easy-to-use tools are available for evaluating both diabetes self-management and anxiety disorders; however, it is known that different cultures can have different metabolic, mental and behavioural characteristics and, thus, it is necessary to validate these instruments before drawing conclusions.

With these premises, our study aimed to translate, culturally adapt for Romanian patients and validate an instrument used for assessing diabetes self-management, the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ), respectively an instrument used for assessing an anxiety disorder - namely the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

In this cross-sectional, non-interventional study, we included 117 patients, diagnosed previously with type 1 and type 2 DM, hospitalised in the Diabetes Clinic of the “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency County Hospital, Timisoara, Romania. The subjects were enrolled according to a population-based, consecutive-case principle. All patients provided written informed consent before performing any study procedure or activity. Since this is a cross-sectional, non-interventional study, according to the local protocols it had to be approved only by the local Ethics Committee. The exclusion criteria have been the inability to provide informed consent and to provide accurate anamnestic data or any diseases or parameters which, in the investigators’ opinions, could lead to biases in the study results.

2.2. Clinical, Anthropometric and Laboratory Data

Detailed characteristics of the studied sample, presented in

Table 1, have been collected from the patients’ medical records. HbA1c, uric acid, lipid profile, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, glomerular filtration rate, TSH and FT

4 measurements were performed after at least 12 h of fasting, using standardised methods. The diagnosis of retinopathy was established using a fundoscopic examination, while the diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy was established using standardised sensation tests. The patients’ characteristics at enrolment were very similar to the ones of the general population of Romanian patients with DM and, thus, the studied sample was highly representative of this population.

2.3. Diabetes Self-Management

The quality of diabetes-related self-management activities was assessed using two instruments—the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire (SDSCA) and the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ).

The SDSCA is a validated self-report tool for measuring diabetes self-management in adults. Eleven items assess the frequencies of multiple diabetes-related and lifestyle activities during the previous week or month. Patients are asked to mark the number of days per week in which they had a healthy or unhealthy diet (4 questions), in which they participated in specific types of physical activity (2 questions), in which they measured their blood glucose levels (2 questions), in which they performed foot-care activities (2 questions) and in which they smoked (1 question + if yes, the number of cigarettes per day). After receiving written permission from the Oregon Research Institute to use the SDSCA, the included patients were instructed to answer the 11 items of this instrument [

21].

The other questionnaire, the DSMQ, an instrument still requiring validation in the population of Romanian patients with DM, is also used to assess behaviours associated with self-care for this noncommunicable disease. It consists of 16 items that cover different aspects of self-care in these individuals: glucose-level management, dietary control, physical activity and patient–physician interaction. Subjects are asked to rate the extent to which each item applied to them in the past 8 weeks (0—does not apply to me, 3—applies to me very much). After receiving written permission from the Mapi Research Trust, the included patients were asked to answer the items twice (the second time with a day in between the responses) [

22].

2.4. Anxiety Assessment

Anxiety was evaluated using two instruments—the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN).

The GAD-7 is an instrument useful in assessing anxiety. It consists of 7 items and subjects are asked to mark the degree in which the described feelings bothered them in the past 2 weeks (0—not at all, 3—nearly every day). This validated tool was already available in Romania and patients were instructed to answer every item [

23].

The SPIN, still requiring validation in the population of Romanian patients with DM, is used in screening for and the measuring of the severity of social anxiety disorder. It includes 17 items and a higher score indicates more severe symptoms such as fear, avoidance and others experienced by subjects in various social situations. The answers are arranged on a five-point scale describing the extent in which each statement applied to the patient in the past week (0—not at all, 4—extremely). The questionnaire was translated in Romanian after receiving written permission from the authors and then patients were asked to answer the items twice (the second time with a day in between the responses) [

24].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data have been recorded and analysed using SPSS v.17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation for numerical variables with Gaussian distribution and median [interquartile range] for numerical variables with non-parametric distribution, respectively, as a percentage from the subgroup’s total. To assess the normality of the numerical variables’ distribution, the Shapiro–Wilk method was used.

The statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed using the unpaired t-Student test (numerical variables with Gaussian distribution) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (numerical variables with non-parametric distribution), respectively, and the Chi-Square test for nominal variables.

In validating the aforementioned questionnaires, we used three analyses: the reliability (internal consistency), the reproducibility and the external validity.

The sample size of the studied lot was calculated prior to enrolment, based on previous similar literature data, to provide a confidence level of 95% and a statistical power of at least 80%. In this study, a p-value lower than 0.05 was considered to be the threshold of statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ)

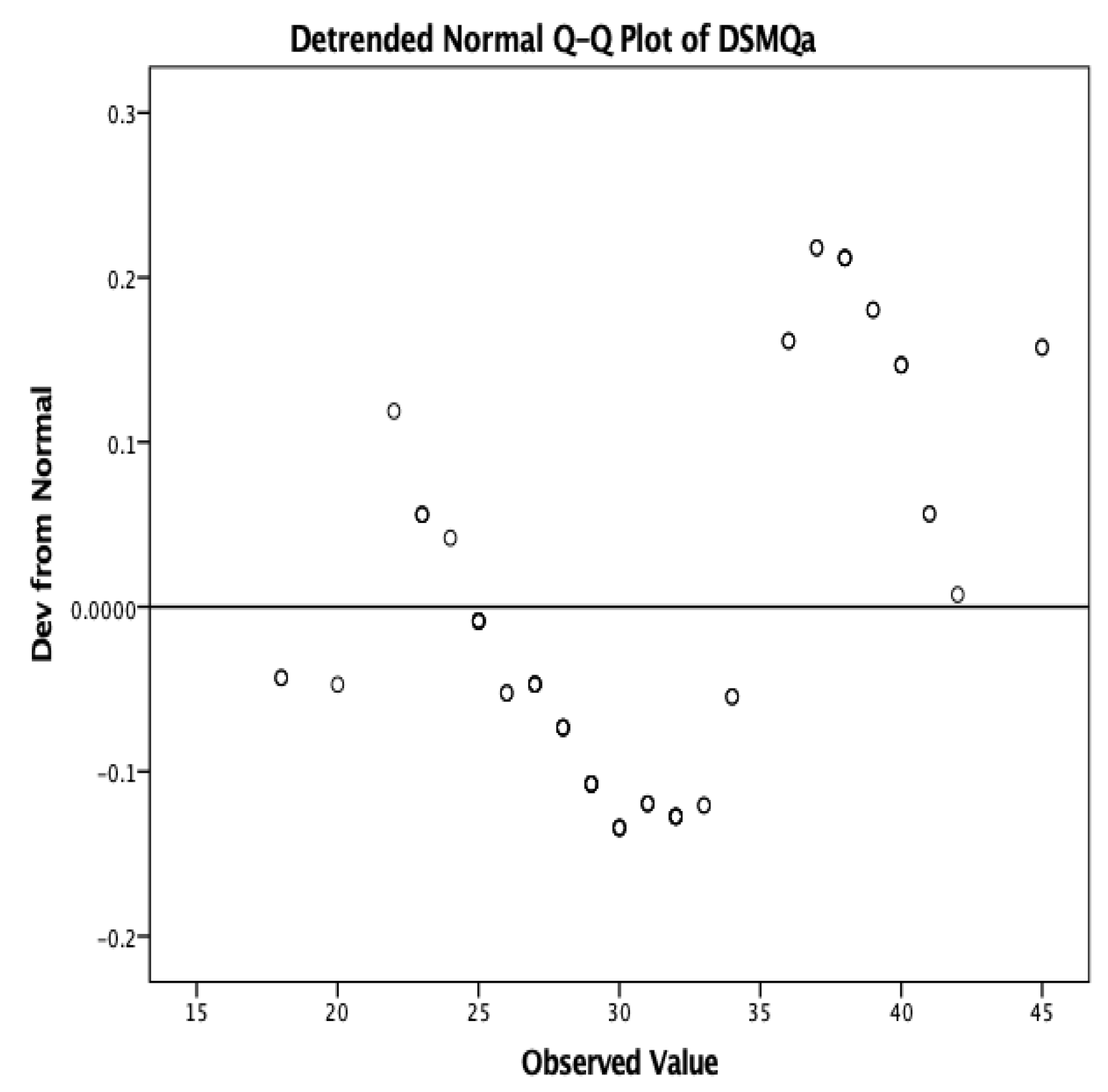

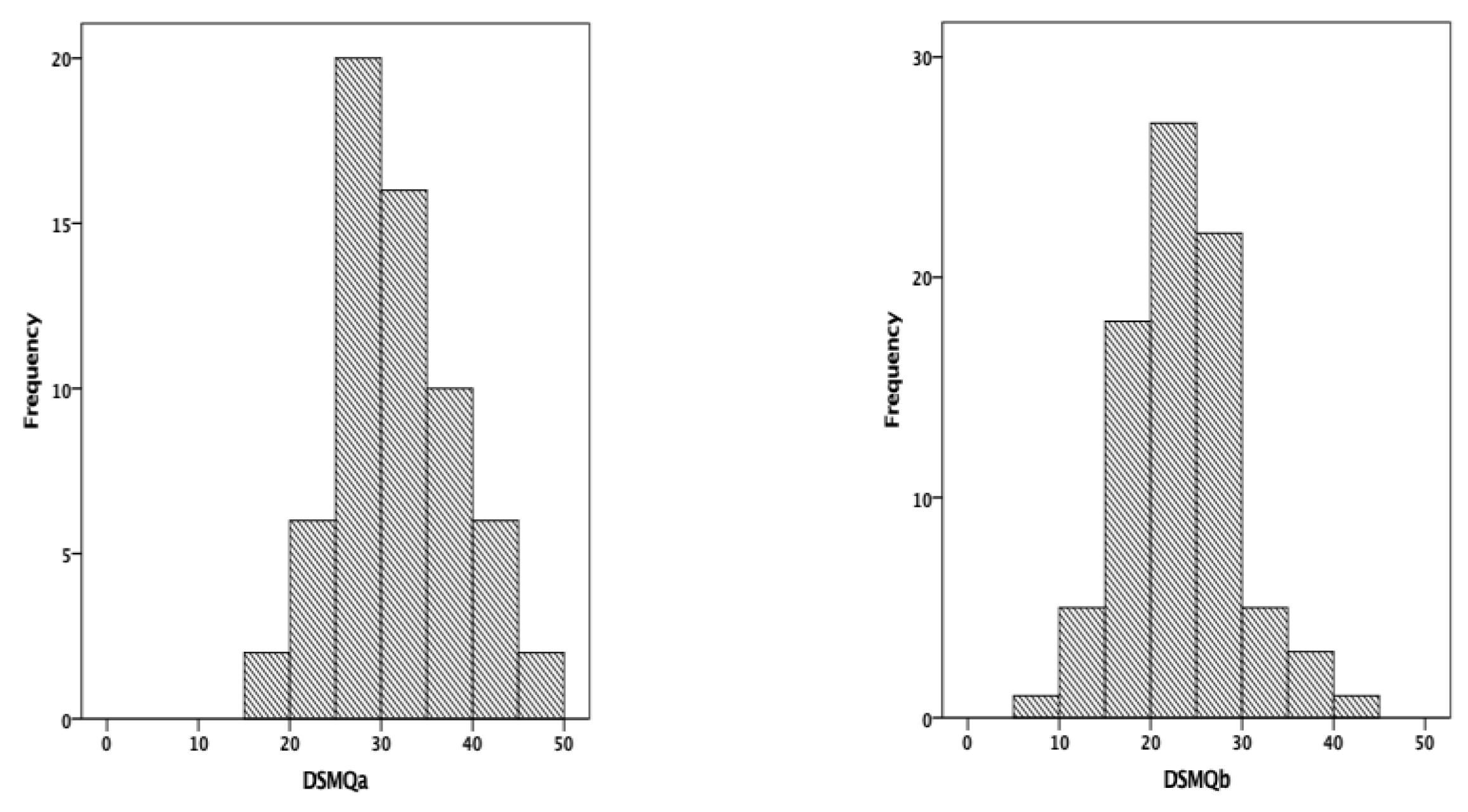

3.1.1. DSMQ Score Distribution

In both initial and follow-up administrations of the DSMQ, 117 responses were recorded. The median scores were 31.13 for the initial evaluation and 22.77 for the final evaluation. The distribution of the scores was unimodal, Gaussian, Shapiro–Wilk = 0.977,

p = 0.297 (

Figure 1).

3.1.2. Acceptability, Ceiling and Floor Effect

At both initial and follow-up evaluation, all the subjects (n = 117) responded to all of the DSMQ items. The median time needed for completion was 2 min and 28 s (minimum 1 min and 45 s, maximum 3 min and 10 s). Regarding the total score, there was no aggregation at the top end of the scale, while the maximum number of points has not been reached by any of the participants. The minimum possible score was also in the desired range, without any participants scoring the minimum number of points; thus, the floor and ceiling effects have been ruled out.

3.1.3. Reliability

The internal consistency of the DSMQ for the Romanian population of patients with DM was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha method. The questionnaire has proven to have acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.683 [0.555–0.787] 95% CI in the first evaluation and Cronbach’s α = 0.794 [0.720–0.866] 95% CI in the second evaluation. At the same time, for both instances there was a high inter-item correlation with a low inter-item covariance (

Table 2).

3.1.4. External Validity

The DSMQ has shown a weak, positive correlation with a previously validated questionnaire, the SDSCA, in both first (Spearman’s rho = 0.070) and second (Spearman’s rho = 0.162) measurements, however without statistical significance (

p = 0.595,

p = 0.156, respectively) (

Figure 2).

3.1.5. Reproducibility

With the test–retest assessment, a statistically significant, moderate, negative correlation was shown between the two measurements of the DSMQ (Spearman’s rho = −0.357,

p = 0.004), while the medians of the scores that have resulted from the two measurements have been 30 and 22, respectively (

Figure 3).

3.2. Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN)

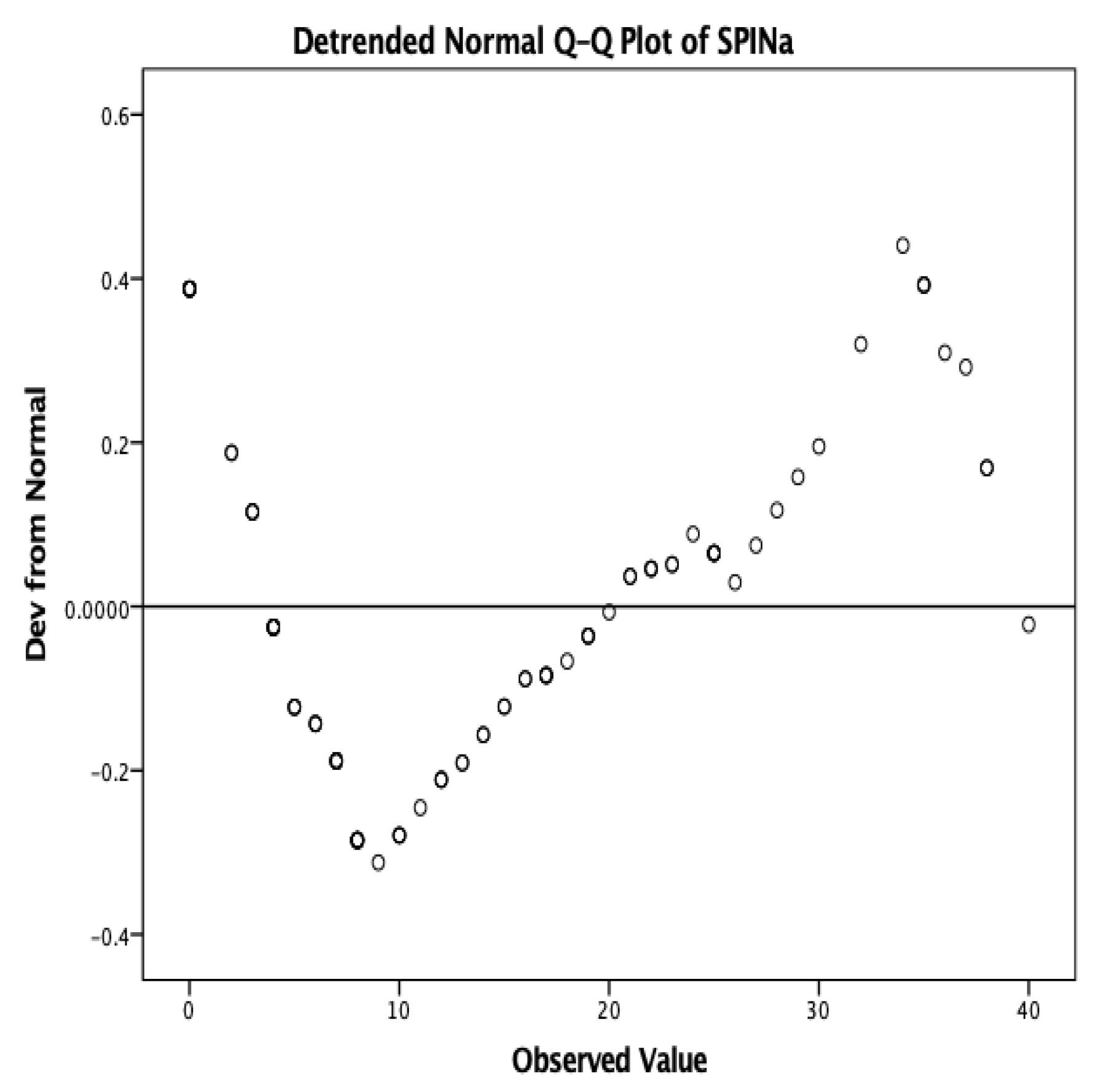

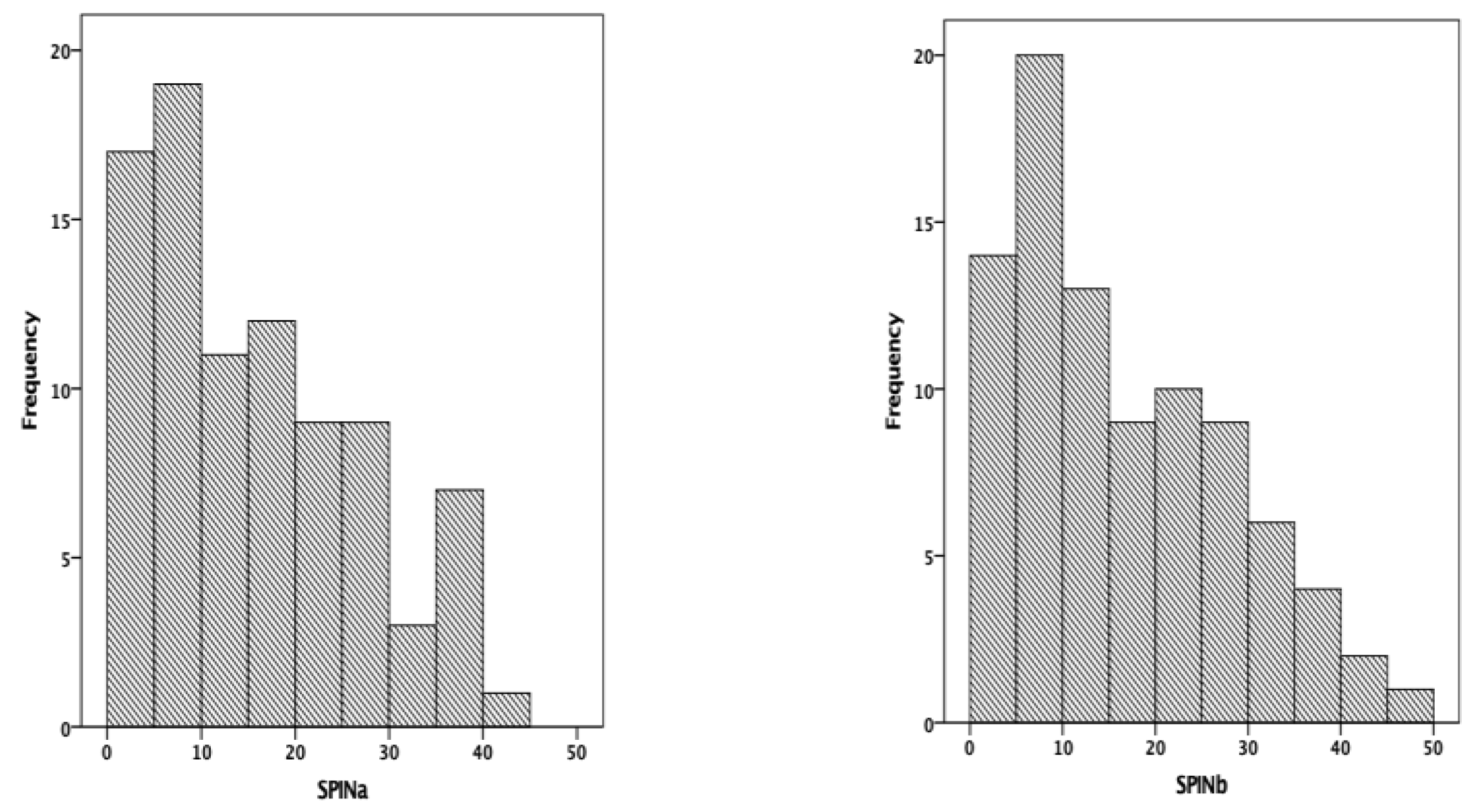

3.2.1. SPIN Score Distribution

In both the first and second administrations of the SPIN, 117 responses were received. The median scores were 15.10 for the initial evaluation and 15.73 for the final evaluation. The distribution of the scores was unimodal, non-Gaussian, Shapiro–Wilk = 0.936,

p < 0.001 (

Figure 4).

3.2.2. Acceptability, Ceiling and Floor Effect

In both the first and second evaluation, every subject (n = 117) responded to all of the SPIN items. The median time for completing the questionnaire was 3 min and 19 s (minimum 2 min and 10 s, maximum 3 min and 48 s). Regarding the total score, no aggregation at the top end of the scale was recorded, while the maximum number of points has not been reached by any of the participants. Furthermore, there were not any participants that scored the minimum number of points; thus, the floor and ceiling effects have been excluded.

3.2.3. Reliability

The internal consistency of the SPIN for Romanian patients with DM was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha method. The questionnaire has proven to have good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.892 [−0.044–1.098] 95% CI in the first measurement and Cronbach’s α = 0.898 [−0.009–1.162] 95% CI in the second measurement. At the same time, for both instances there was a high inter-item correlation and a low inter-item covariance (

Table 3).

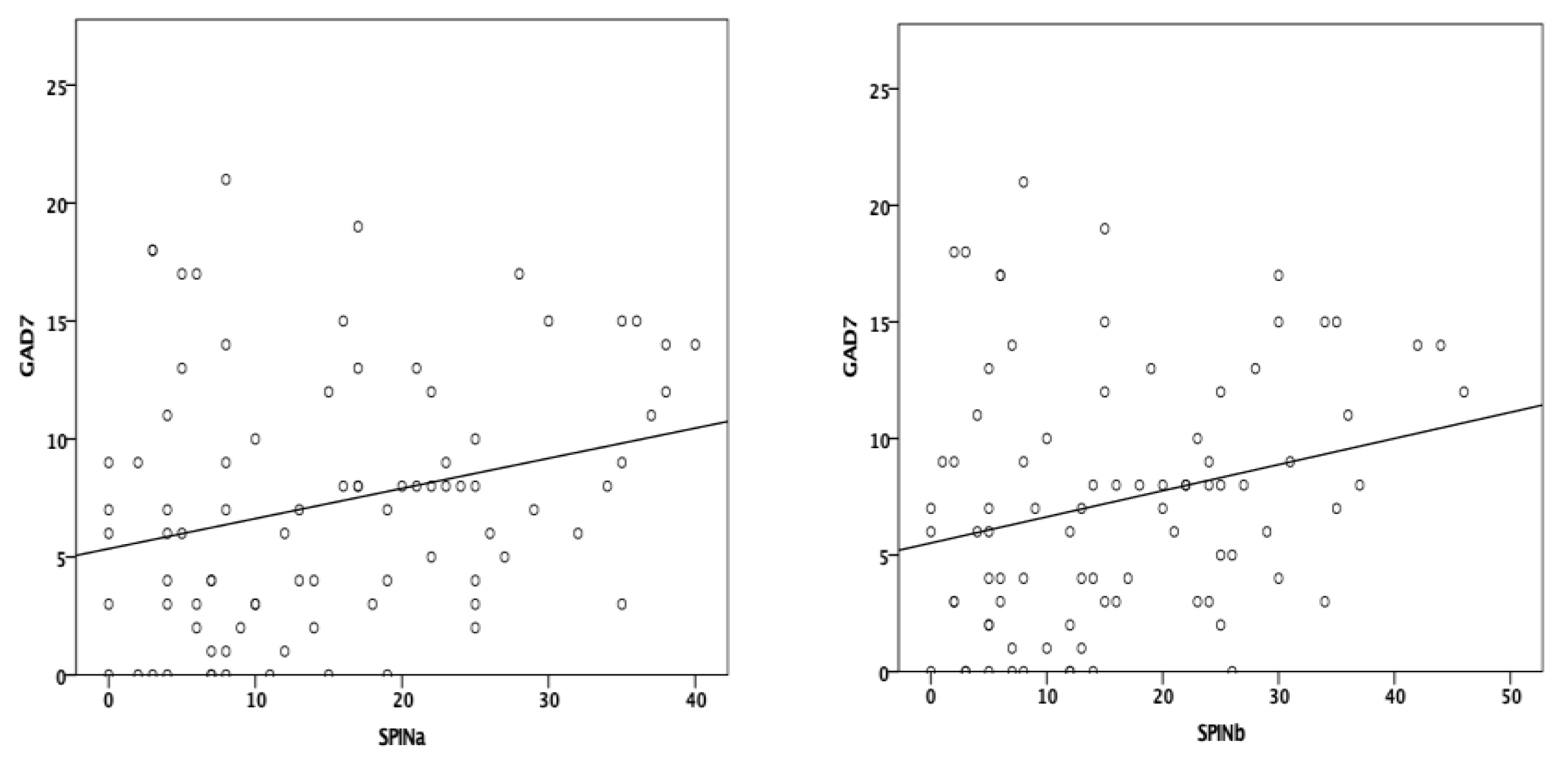

3.2.4. External Validity

The SPIN has shown a statistically significant, weak, positive correlation with a previously validated questionnaire, the GAD-7, in both the initial (Spearman’s rho = 0.274,

p < 0.001) and follow-up (Spearman’s rho = 0.256,

p = 0.018) measurements (

Figure 5).

3.2.5. Reproducibility

With the test–retest assessment, a strong positive correlation with statistical significance was shown between the two administrations of the SPIN (Spearman’s rho = 0.971,

p < 0.001), while the median of the scores that has resulted from the two measurements has been 13 and the differences between the two measurements did not have statistical significance (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The results of this research have shown that the SPIN could become a useful instrument in the diagnosis and assessment of the severity of social phobia in patients with DM in Romania since it has proven to have good internal consistency, excellent acceptability and a test–retest reliability that is similar to other more complex instruments. Moreover, all of the enrolled patients have answered all of its items, in both measurements, in a short duration of time, with a median of 3 min and 19 s.

The validity of the SPIN was also proven to be good since a positive correlation with statistical significance was shown between the scores resulting from this questionnaire and from the GAD-7, a previously validated instrument. The weak correlation between these results could be explained by the two different conditions assessed by the two self-administered questionnaires, namely social phobia and generalised anxiety disorder. However, the aforementioned results and the validation of the SPIN in multiple other trials in different countries on various continents support the usage of this instrument for the screening of social phobia in patients—including Romanian patients—with DM [

25,

26].

Similar results of this study have been shown with regard to the DSMQ, an instrument designed to assess diabetes self-management. However, although this questionnaire has proven to have acceptable internal consistency and has been used with ease by all of the enrolled patients, its weak positive correlation with a previously validated tool, namely the SDSCA, has not reached statistical significance, hence the necessity of further evidence before stating its validity for Romanian patients with DM. This finding could be explained by the difficulty in assessing diabetes self-management with a standardised test and not through a partially guided interview, direct observation or interpretation of glycaemic control or cardiometabolic risk factors. Nevertheless, the DSMQ has already been validated in diverse subpopulations across the globe, with more favourable results in various studies showing data that encourage future research regarding this valuable tool [

27,

28].

The strengths of this research include the consecutive enrolment of the subjects that resulted in a heterogenous cohort of individuals, with or without social phobia, with diverse values of age, metabolic parameters, DM evolution and complications, antihyperglycemic agents and diabetes self-care behaviours. Moreover, this study is the first of its kind in Romania, and the first one that validated the translated and culturally adapted SPIN version, while being the first step in validating the DSMQ. Furthermore, we have addressed sources of potential bias through using standardised methods of assessing complications of diabetes and characteristics of patients, through a clearly defined study population with enrolment according to a consecutive-case principle, with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, through using well-known instruments in evaluating anxiety and diabetes self-management and through not interfering with the completion of the four questionnaires by the patients.

The main drawback of this research consists of the potential discrepancy between the general attributes of the enrolled patients and the population of individuals with DM from Romania, since we only included patients admitted in the Diabetes Clinic of the “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency County Hospital, Timisoara, Romania. However, the sample size was calculated to provide a statistical power level that would allow the inference of the results for the entire previously mentioned population.

The importance of this study lies in the increasing options regarding validated questionnaires that can be used to assess anxiety disorders and diabetes self-management accurately and early in the management of patients with DM from Romania, in a non-time-consuming and even self-administered manner, an essential characteristic when including new procedures into routine clinical practice. The analysis of self-management in patients with DM could have beneficial effects in the prevention of acute and chronic complications and in slowing the progression of chronic complications that are already present, while the detection of social phobia and other anxiety-related conditions could contribute to an improved prognosis and quality of life of DM individuals through an interdisciplinary approach.

5. Conclusions

The SPIN self-administered questionnaire, translated in Romanian and culturally adapted, is a valid instrument for the screening of social phobia in individuals with DM, while the DSMQ, that can be used for evaluating diabetes self-management behaviours, requires additional data for its validation. The SPIN has proven to have excellent acceptability and reliability and a test–retest performance comparable to other more complex tools that can be used to assess anxiety disorders and, thus, is a valuable and reliable questionnaire that can be used in daily clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G., B.T., R.T. and S.P.; methodology, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G. and B.T.; software, B.T., R.T. and S.P.; validation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G., S.L. and S.P.; formal analysis, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.D. (Loredana Deaconu), S.L. and S.P.; investigation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G., B.T., L.D. (Loredana Deaconu) and S.L.; resources, B.T., R.T. and S.P.; data curation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G., S.L. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G., L.D. (Loredana Deaconu) and S.L.; writing—review and editing, B.T., R.T. and S.P.; visualisation, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G. and B.T.; supervision, B.T., R.T. and S.P.; project administration, L.D. (Laura Diaconu), L.G. and B.T.; funding acquisition, B.T., R.T. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Pius Brinzeu” Emergency Hospital Timisoara, Romania.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to privacy restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author after the request’s approval by the hospital’s ethics committee. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions according to the hospital’s internal regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IDF Diabetes Atlas | Tenth Edition. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- de Groot, M.; Golden, S.H.; Wagner, J. Psychological conditions in adults with diabetes. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. S1), S46–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, S.; Behnezhad, S. Diabetes and anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2019, 009121741983740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ornelas Maia, A.C.C.; Braga A de, A.; Brouwers, A.; Nardi, A.E.; de Oliveira e Silva, A.C. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with diabetes types 1 and 2. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tareen, R.S.; Tareen, K. Psychosocial aspects of diabetes management: Dilemma of diabetes distress. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, A.B.; Anderson, R.J.; Freedland, K.E.; Clouse, R.E.; Lustman, P.J. Prevalence of anxiety in adults with diabetes: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mut-Vitcu, G.; Timar, B.; Timar, R.; Oancea, C.; Citu, I.C. Depression influences the quality of diabetes-related self-management activities in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Intervig. Aging. 2016, 11, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.J.; Grigsby, A.B.; Freedland, K.E.; De Groot, M.; McGill, J.B.; Clouse, R.E.; Lustman, P.J. Anxiety and Poor Glycemic Control: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2002, 32, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, K.; Johnson, J.A.; Skogen, J.C.; Manuel, D.; Øverland, S.; Sivertsen, B.; Colman, I. Type 2 Diabetes and Comorbid Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Longitudinal Associations With Mortality Risk. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickett, A.; Tapp, H. Anxiety and diabetes: Innovative approaches to management in primary care. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1724–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn-Nemeth, P.; Quinn, L.; Penckofer, S.; Park, C.; Hofer, V.; Burke, L. Fear of hypoglycemia: Influence on glycemic variability and self-management behavior in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. 5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44 (Suppl. S1), S53–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, A.; Reimer, A.; Hermanns, N.; Huber, J.; Ehrmann, D.; Schall, S.; Kulzer, B. Assessing Diabetes Self-Management with the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) Can Help Analyse Behavioural Problems Related to Reduced Glycaemic Control. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrvala, C.A.; Sherr, D.; Lipman, R.D. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, A.; Rygg, L.; Lisulo, M.; Rise, M.B.; Fretheim, A. Group based diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, J.; Conn, V.S. Meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self-management training. Diabetes Educ. 2008, 34, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, I.; Ahmed, T.; Li, Q.; Stetson, B.; Ruggiero, L.; Burton, K.; Rosenthal, D.; Fitzner, K. Assessing the Value of the Diabetes Educator. Diabetes Educ. 2011, 37, 638–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Yao, Q.; Li, L.; Song, R.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.A. Diabetes self-management education reduces risk of all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2017, 55, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoinoiu, B.; Jiga, L.P.; Nistor, A.; Dornean, V.; Barac, S.; Miclaus, G.; Ionac, M.; Hoinoiu, T. Chronic Hindlimb Ischemia Assessment; Quantitative Evaluation Using Laser Doppler in a Rodent Model of Surgically Induced Peripheral Arterial Occlusion. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobert, D.J.; Hampson, S.E.; Glasgow, R.E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Gahr, A.; Hermanns, N.; Kulzer, B.; Huber, J.; Haak, T. The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): Development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T.; Erik Churchill, L.; Sherwood, A.; Foa, E.; Weisler, R.H. Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN). New self- rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Lopez, L.J.; Bermejo, R.M.; Hidalgo, M.D. The Social Phobia Inventory: Screening and cross-cultural validation in Spanish adolescents. Span J. Psychol. 2010, 13, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.F.; Wang, S.J.; Juang, K.D.; Fuh, J.L. Use of the Chinese (Taiwan) Version of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) Among Early Adolescents in Rural Areas: Reliability and Validity Study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2009, 72, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhsh, A.; Lee, S.W.H.; Pusparajah, P.; Schmitt, A.; Khan, T.M. Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) in Urdu. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márkus, B.; Hargittay, C.; Iller, B.; Rinfel, J.; Bencsik, P.; Oláh, I.; Kalabay, L.; Vörös, K. Validation of the revised Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ-R) in the primary care setting. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).