Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Some Characteristic Features of People Recovered from COVID-19 in Turkey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Survey Region and Sample Size

2.3. Survey Method

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Data on Some Characteristic Features of the Participants

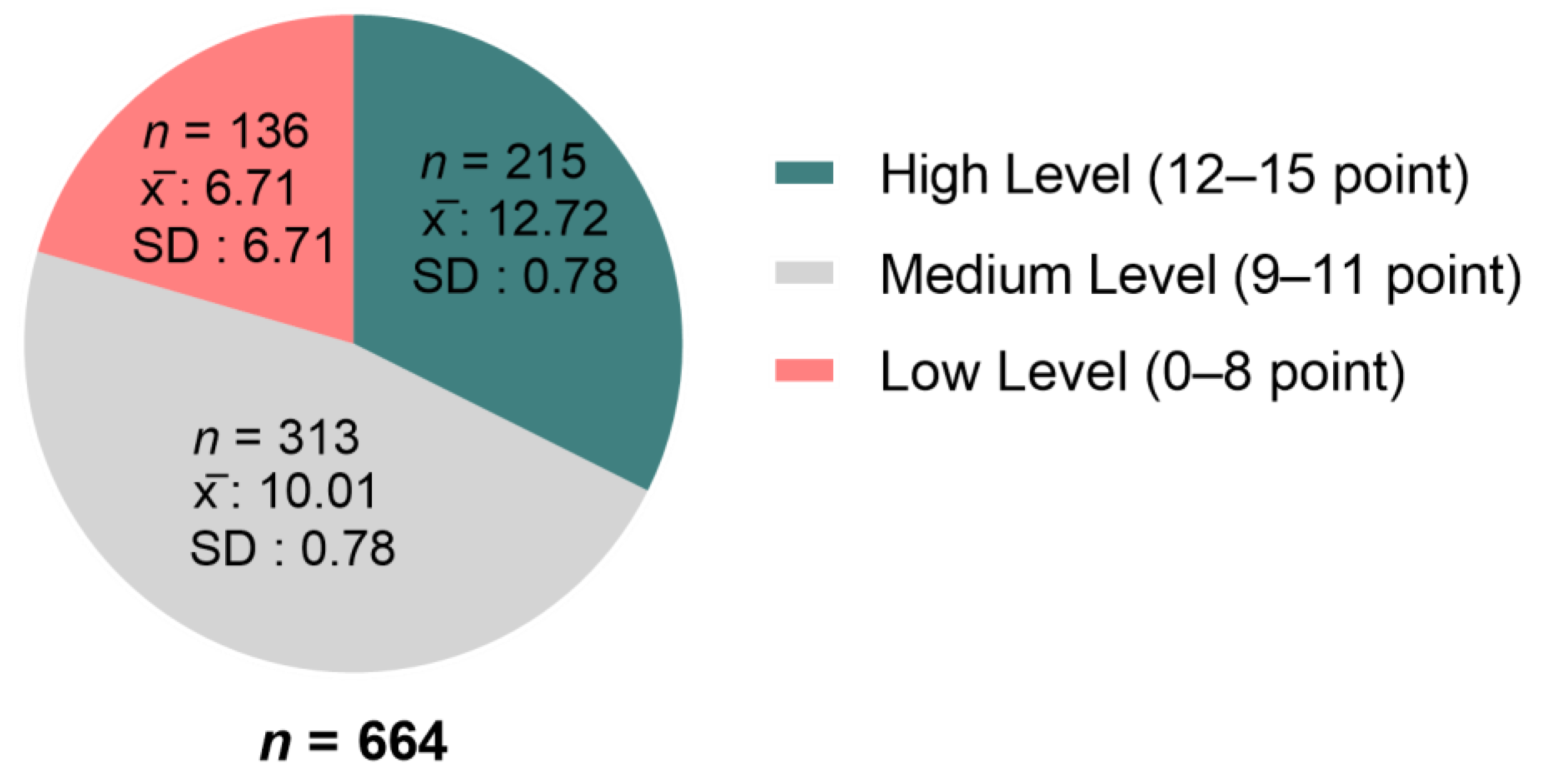

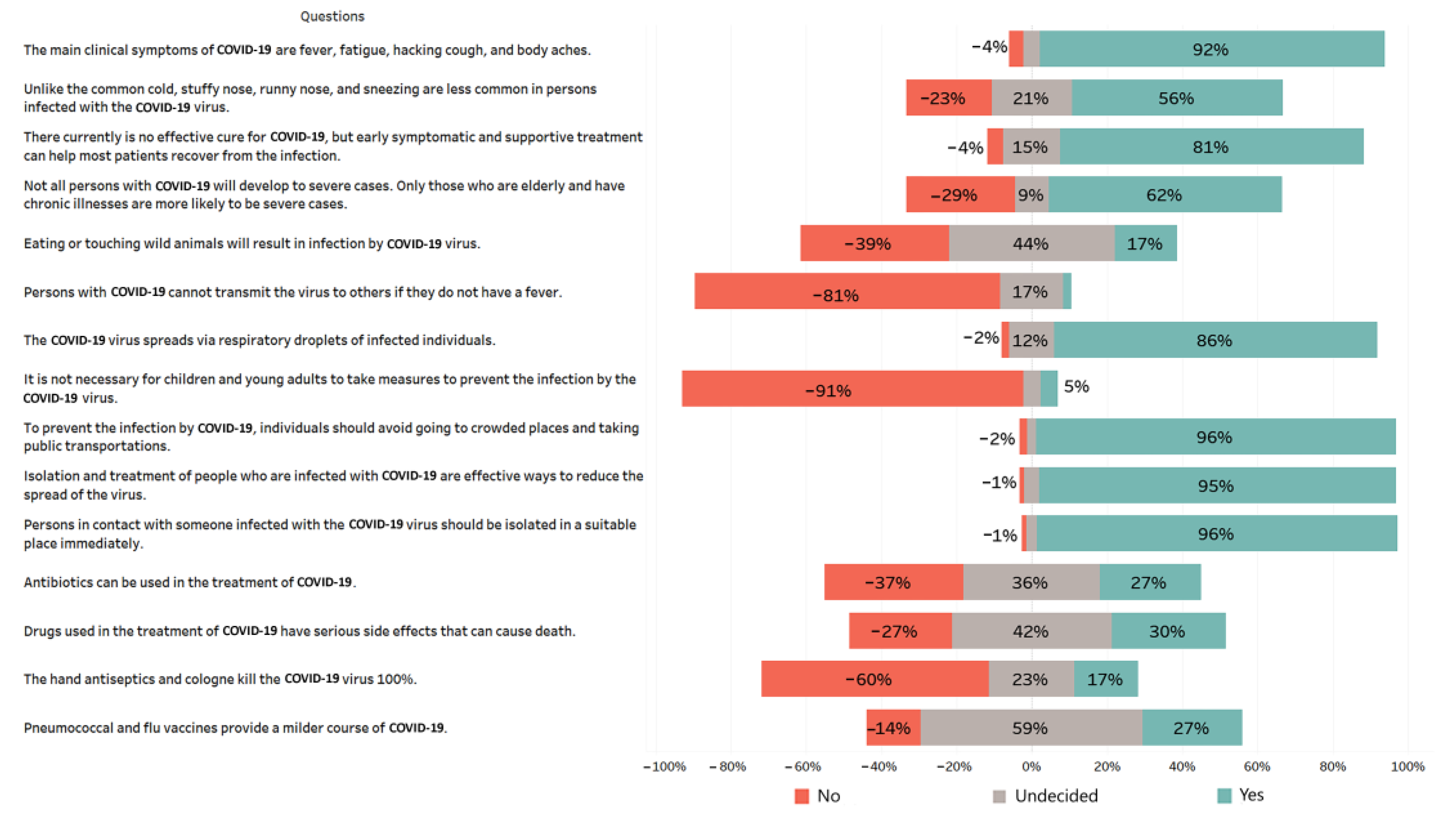

3.3. Data on Knowledge Levels and Scores of the Participants in Relation with COVID-19

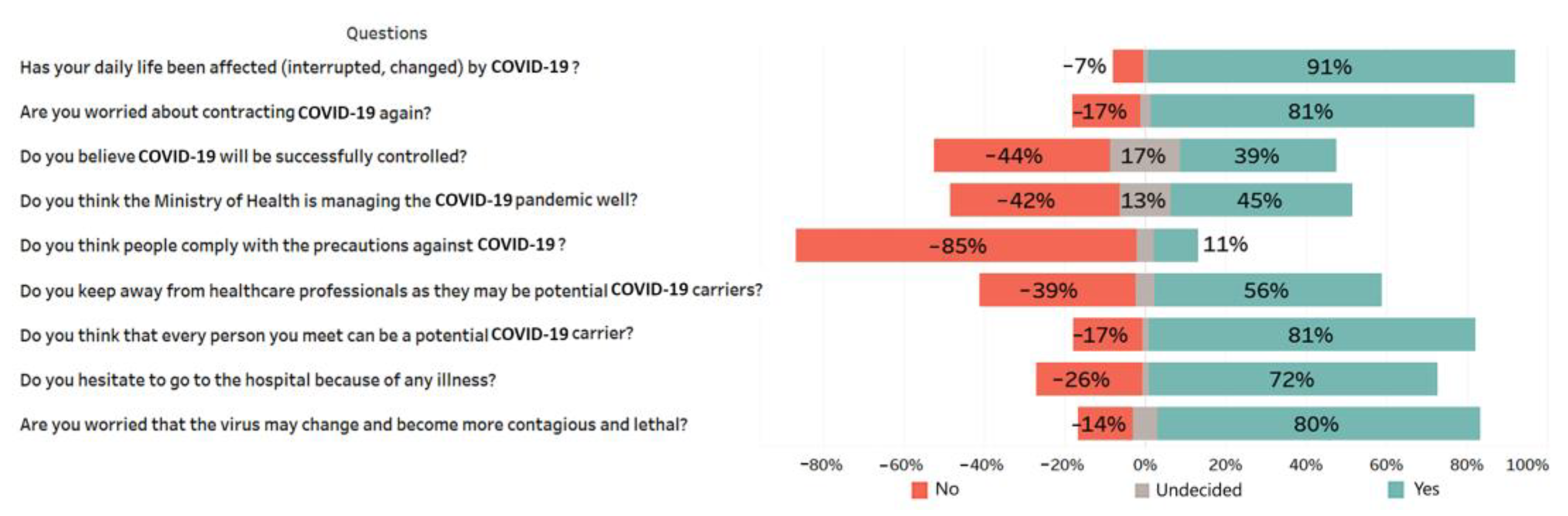

3.4. Attitudes of the Participants towards COVID-19

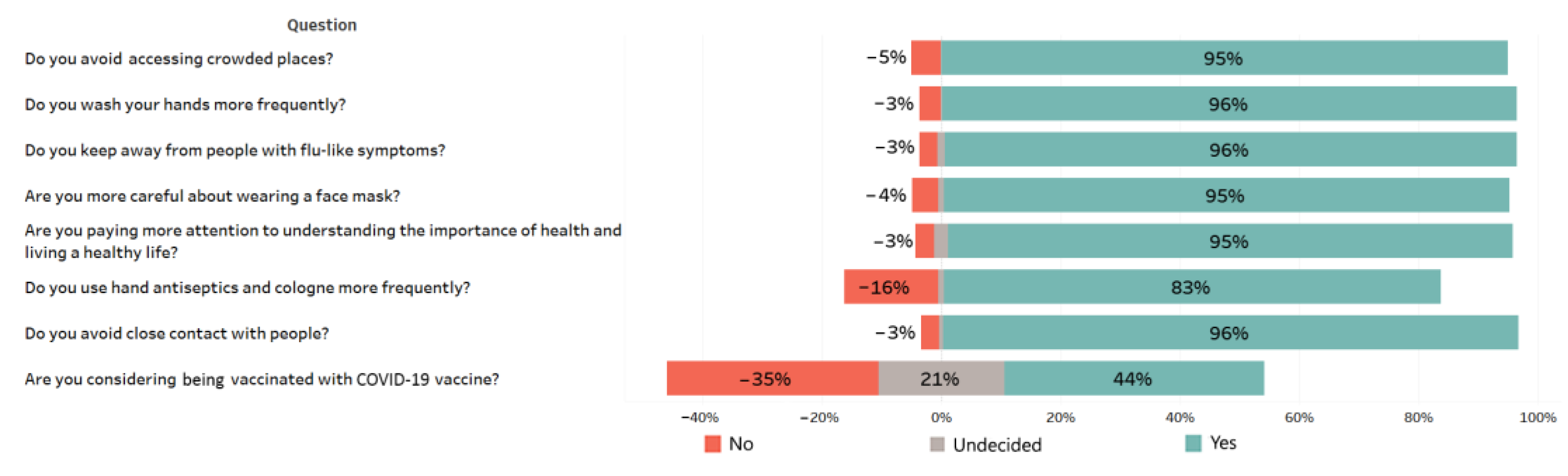

3.5. Practices of the Participants towards COVID-19

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbilek, Y.; Pehlivantürk, G.; Özgüler, Z.Ö.; Meşe, E.A. COVID-19 outbreak control, example of ministry of health of Turkey. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zwart, O.; Veldhuijzen, I.K.; Elam, G.; Aro, A.R.; Abraham, T.; Bishop, G.D.; Voeten, H.A.C.M.; Richardus, J.H.; Brug, J. Perceived Threat, Risk Perception, and Efficacy Beliefs Related to SARS and Other (Emerging) Infectious Diseases: Results of an International Survey. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Angawi, K.; Alshareef, N.; Qattan, A.M.N.; Helmy, H.Z.; Abudawood, Y.; AlQurashi, M.; Kattan, W.M.; Kadasah, N.A.; Chirwa, G.C.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Toward COVID-19 Among the Public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Tang, F.; Wang, Y.; Nie, H.; Zhang, L.; You, G. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azlan, A.A.; Hamzah, M.R.; Sern, T.J.; Ayub, S.H.; Mohamad, E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adela, N.; Nkengazong, L.; Ambe, L.A.; Ebogo, J.T.; Mba, F.M.; Goni, H.O.; Nyunai, N.; Nhgonde, M.C.; Oyono, J.-L.E. Knowledge, attitudes, practices of/towards COVID 19 preventive measures and symptoms: A cross-sectional study during the exponential rise of the out-break in Cameroon. PLoS Negl. Trop Dis. 2020, 14, e0008700. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Zhong, B.-L.; Luo, W.; Li, H.-M.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Liu, X.-G.; Li, W.-T.; Li, Y. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: A quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lian, J.S.; Hu, J.H.; Gao, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Hao, S.R.; Jia, H.Y.; Cai, H.; Zhang, X.L.; et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut 2020, 69, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillett, R.L.; Sevinsky, J.R.; Hartley, P.D.; Kerwin, H.; Crawford, N.; Gorzalski, A.; Laverdure, C.; Verma, S.C.; Rossetto, C.C.; Jackson, D.; et al. Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: A case study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 21, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Everden, S.; Nikitas, N. A case of COVID-19 reinfection in the UK. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e52–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, V.; Herman, K.; Dapaah-Afriyie, K. Severe, Symptomatic Reinfection in a Patient with COVID-19. Med. J. 2020, 103, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.; Xu, S.-B.; Lin, Y.-X.; Tian, D.; Zhu, Z.-Q.; Dai, F.-H.; Wu, F.; Song, Z.-G.; Huang, W.; Chen, J.; et al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Liao, X.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, T.; Qian, S. Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with Novel Coronavirus Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromos, C.; Rumschlag, T.; Perchyk, T. Hydroxychloroquine is protective to the heart, not harmful: A systematic review. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 37, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Nikitara, K. COVID-19 and smoking: A systematic review of the evidence. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 75, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Health Survey in Turkey. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Turkiye-Saglik-Arastirmasi-2019-33661 (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Kasemy, Z.A.; Bahbah, W.A.; Zewain, S.K.; Haggag, M.G.; Alkalash, S.H.; Zahran, E.; Desouky, D.E. Knowledge, Atti-tude and Practice toward COVID-19 among Egyptians. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.M. Knowledge and Behaviors toward COVID-19 among US Residents during the Early Days of the Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Online Questionnaire. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALdowyan, N.; Abdallah, A.S.; El-Gharabawy, R. Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study about middle east res-piratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) among population in Saudi Arabia. Int. Arch. Med. 2017, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Al-Khal, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards SARS. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2004, 124, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, S. Prevention and treatment knowledge towards SARS of urban population in Jinan. Prev. Med. Trib. 2004, 10, 659–660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Xiu, C.; Chu, Q. Prevention and treatment knowledge and attitudes towards SARS of urban residents in Qing-dao. Prev. Med. Trib. 2004, 10, 407–408. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Graham, M.S.; Joshi, A.D.; Guo, C.-G.; Ma, W.; Mehta, R.S.; Warner, E.T.; Sikavi, D.R.; Lo, C.-H.; et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e475–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. Clin. Med. 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohands, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2020, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 324 | 48.9 |

| Female | 340 | 51.1 | |

| Age range (year) | 15–25 | 124 | 18.7 |

| 25–36 | 241 | 36.3 | |

| 36–50 | 200 | 30.1 | |

| 51 and more | 99 | 14.9 | |

| Marital status | Married | 425 | 64.0 |

| Never married | 224 | 33.8 | |

| Divorced | 15 | 2.3 | |

| Education level | Uneducated | 20 | 3.0 |

| Primary school | 55 | 8.3 | |

| High school | 110 | 16.4 | |

| Associate’s/bachelor’s degree | 372 | 56.1 | |

| Postgraduate | 107 | 16.1 | |

| Residence | Province | 201 | 30.2 |

| Town | 425 | 64.1 | |

| Village | 38 | 5.7 | |

| Occupation | Civil servant | 392 | 59.0 |

| Employee | 83 | 12.5 | |

| Self-employment | 25 | 3.8 | |

| Unemployed | 164 | 24.7 |

| Questions | Answers | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you smoke? | Yes | 199 | 30 |

| No | 465 | 70 | |

| Has there been any change in your smoking habit after you recovered from the disease? | Likewise, I continue to smoke | 109 | 54.8 |

| I reduced smoking | 54 | 27.1 | |

| I quit smoking | 36 | 18.1 | |

| What type of food do you eat most? | Carbohydrate foods | 164 | 24.7 |

| Meat (red and white meat, fish) | 232 | 34.9 | |

| Fruit/vegetables | 176 | 26.5 | |

| Vegan/vegetarian | 6 | 0.9 | |

| Balanced diet | 86 | 13 | |

| Do you have a chronic illness? | Yes | 418 | 63 |

| No | 246 | 37 | |

| How many times did you contract COVID-19? | Once | 638 | 96.1 |

| Twice | 26 | 3.9 | |

| Where did you spend the treatment process of COVID-19? | At home | 627 | 94.4 |

| Polyclinic services | 34 | 5.1 | |

| Intensive care unit | 3 | 0.5 | |

| How long did your illness last? | 0–10 days | 384 | 57.8 |

| 11–20 days | 231 | 34.8 | |

| 21–30 days | 31 | 4.7 | |

| 31 days and more | 18 | 2.7 | |

| What kind of medical support did you receive during your illness? | Medication | 477 | 71.8 |

| Respiratory support | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Medication/respiratory support | 20 | 3 | |

| I refused treatment | 151 | 22.7 | |

| Alternative treatments (herbal herbs, vitamins) | 13 | 2 |

| Features | Number of Participants (%) | Knowledge Score (SD) | t/f | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 324 (48.9) | 10.12 (2.5) | −1.30 | 0.192 a |

| Female | 340 (51.1) | 10.37 (2.1) | |||

| Age range (year) | 15–25 | 124 (18.7) | 10.03 (2.6) | 0.85 | 0.468 b |

| 25–36 | 241 (36.3) | 10.31 (2.3) | |||

| 36–50 | 200 (30.1) | 10.40 (2.3) | |||

| 51 and more | 99 (14.9) | 10.08 (2.0) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 425 (64.0) | 10.20 (2.3) | 0.76 | 0.468 b |

| Never married | 224 (33.8) | 10.30 (2.4) | |||

| Divorced | 15 (2.3) | 10.93 (1.4) | |||

| Education level | Uneducated | 20 (3.0) | 10.00 (2.0) | 5.64 | <0.001 b |

| Primary school | 55 (8.3) | 9.87 (2.4) | |||

| High school | 110 (16.4) | 9.50 (2.4) | |||

| Associate’s/bachelor’s degree | 372 (56.1) | 10.34 (2.3) | |||

| Postgraduate * | 107 (16.1) | 10.94 (2.2) | |||

| Residence | Province | 201 (30.2) | 10.41 (2.3) | 2.40 | 0.09 b |

| Town | 425 (64.1) | 10.24 (2.6) | |||

| Village | 38 (5.7) | 9.50 (2.5) | |||

| Occupation | Civil servant | 392 (59.0) | 10.61 (2.4) | 8.05 | <0.001 b |

| Employee # | 83 (12.5) | 9.50 (2.2) | |||

| Self-employment | 25 (3.8) | 9.64 (2.4) | |||

| Unemployed | 164 (24.7) | 9.85 (2.3) |

| Features | Yes | No | Undecided | χ2 | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male * | 166 (51.2%) | 106 (32.7%) | 52 (16.0%) | 17.531 | <0.001 |

| Female | 123 (36.2%) | 129 (37.9%) | 88 (25.9%) | |||

| Age range (year) | 15–25 | 43 (34.7%) | 46 (37.1%) | 35 (28.2%) | 17.112 | 0.009 |

| 25–36 | 99 (41.1%) | 83 (34.4%) | 59 (24.5%) | |||

| 36–50 * | 97 (48.5%) | 77 (38.5%) | 26 (13.0%) | |||

| 51 and more | 50 (50.5%) | 29 (29.3%) | 20 (20.2%) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 198 (46.6%) | 146 (34.4%) | 81 (19.1%) | 6.489 | 0.165 |

| Never married | 84 (37.5%) | 83 (37.1%) | 57 (25.4%) | |||

| Divorced | 7 (46.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | |||

| Education level | Uneducated | 8 (40.0%) | 7 (35.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | 6.936 | 0.544 |

| Primary school | 23 (41.8%) | 23 (41.8%) | 9 (16.4%) | |||

| High school | 52 (47.3%) | 34 (30.9%) | 24 (21.8%) | |||

| Associate’s/bachelor’s degree | 155 (41.7%) | 130 (34.4%) | 87 (23.4%) | |||

| Postgraduate | 51 (47.7%) | 41 (38.3%) | 15 (14.0%) | |||

| Residence | Province | 83 (41.3%) | 84 (41.8%) | 34 (16.9%) | 6.735 | 0.151 |

| Town | 187 (44.0%) | 139 (32.7%) | 99 (23.3%) | |||

| Village | 19 (50.0%) | 12 (31.6%) | 7 (18.4%) | |||

| Occupation | Civil servant | 189 (48.2%) | 136 (34.7%) | 67 (17.1%) | 23.072 | 0.001 |

| Employee | 30 (36.1%) | 33 (39.8%) | 20 (24.1%) | |||

| Self-employment | 13 (52%) | 11 (44%) | 1 (4%) | |||

| Unemployed * | 57 (34.8%) | 55 (33.5%) | 52 (31.7%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yakut, S.; Karagülle, B.; Atçalı, T.; Öztürk, Y.; Açık, M.N.; Çetinkaya, B. Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Some Characteristic Features of People Recovered from COVID-19 in Turkey. Medicina 2021, 57, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050431

Yakut S, Karagülle B, Atçalı T, Öztürk Y, Açık MN, Çetinkaya B. Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Some Characteristic Features of People Recovered from COVID-19 in Turkey. Medicina. 2021; 57(5):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050431

Chicago/Turabian StyleYakut, Seda, Burcu Karagülle, Tuğçe Atçalı, Yasin Öztürk, Mehmet Nuri Açık, and Burhan Çetinkaya. 2021. "Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Some Characteristic Features of People Recovered from COVID-19 in Turkey" Medicina 57, no. 5: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050431

APA StyleYakut, S., Karagülle, B., Atçalı, T., Öztürk, Y., Açık, M. N., & Çetinkaya, B. (2021). Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices and Some Characteristic Features of People Recovered from COVID-19 in Turkey. Medicina, 57(5), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57050431