Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma―Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and RNA Extraction

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatics Databases

3. Results

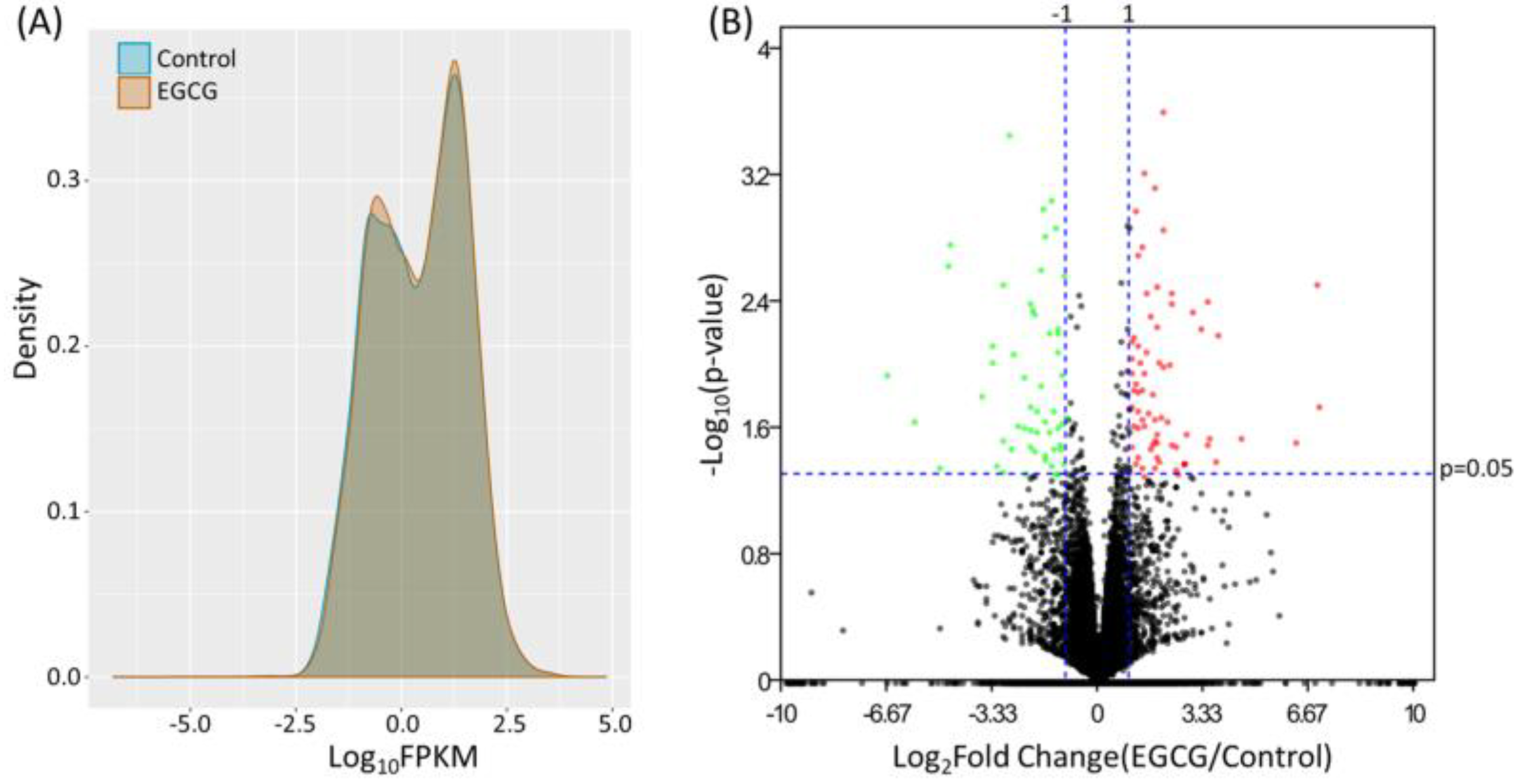

3.1. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes in EGCG-Treated Bladder TCC Cells

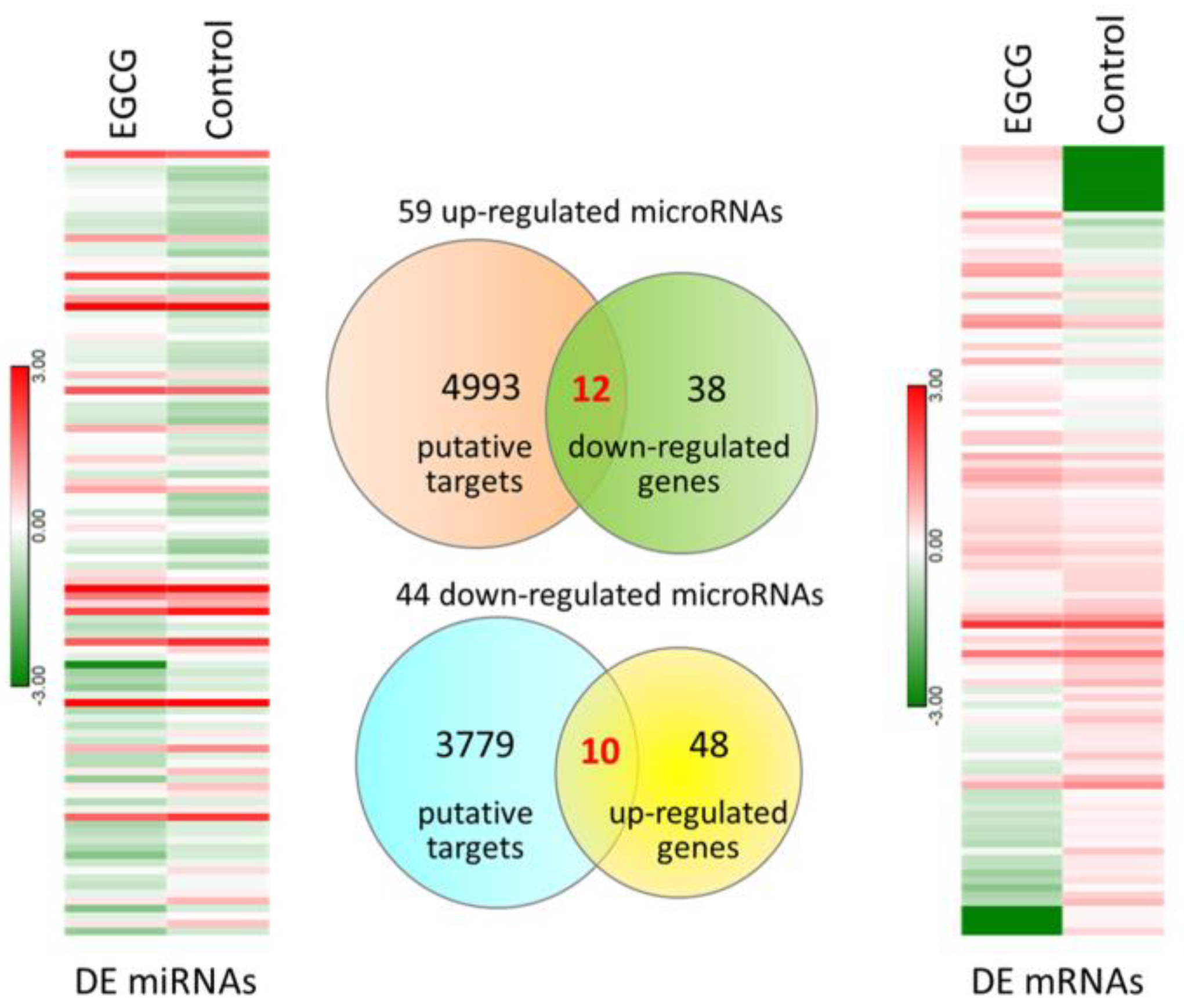

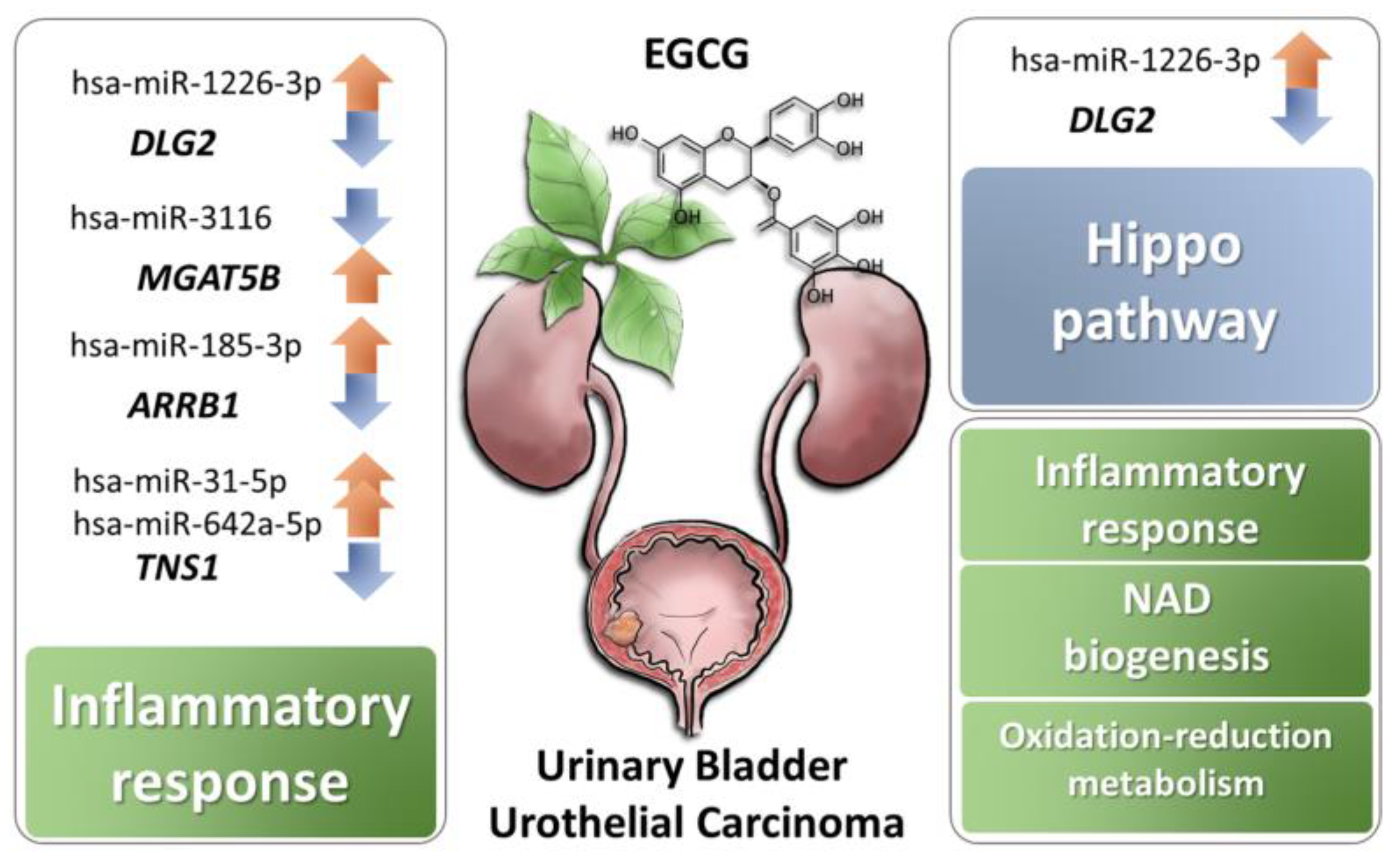

3.2. Exploring Potentially Altered miRNA–mRNA Interactions in EGCG-Treated Bladder TCC Cells

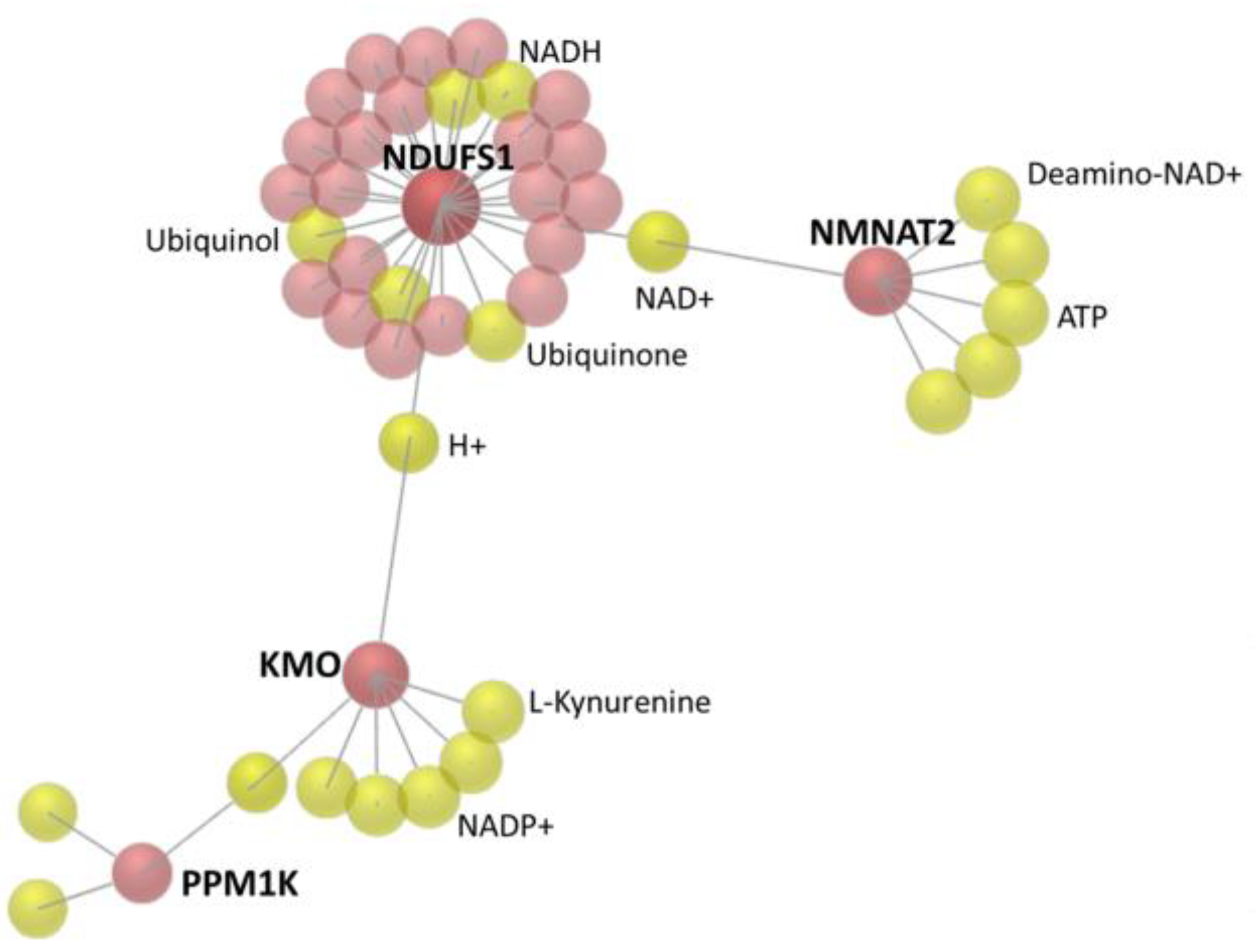

3.3. The 22 Candidate Genes were Involved in NAD Biosynthesis, Inflammatory Response and Cancer

3.4. Enriched Biological Functions Among Differentially Expressed Genes in EGCG-Treated Bladder TCC Cells

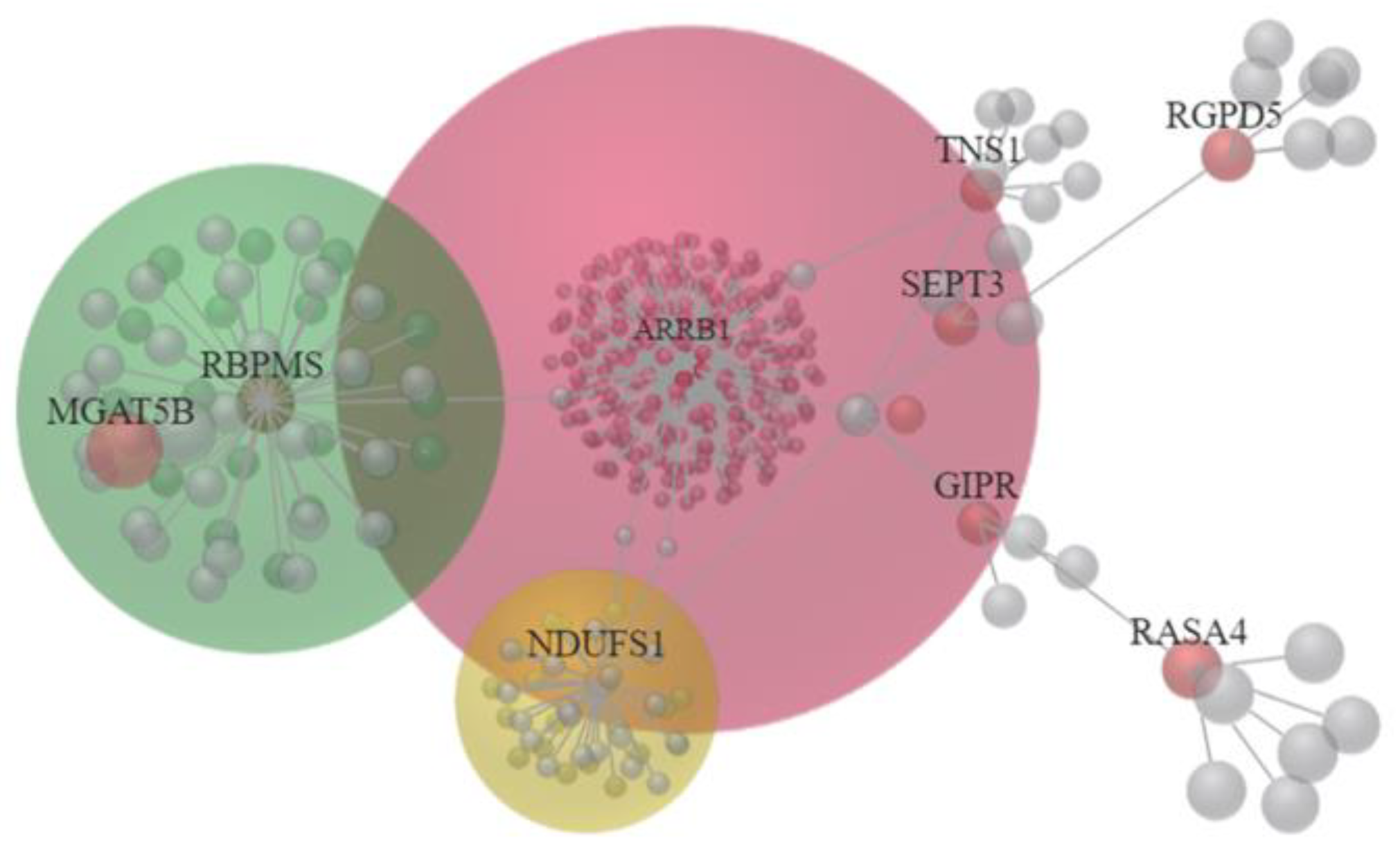

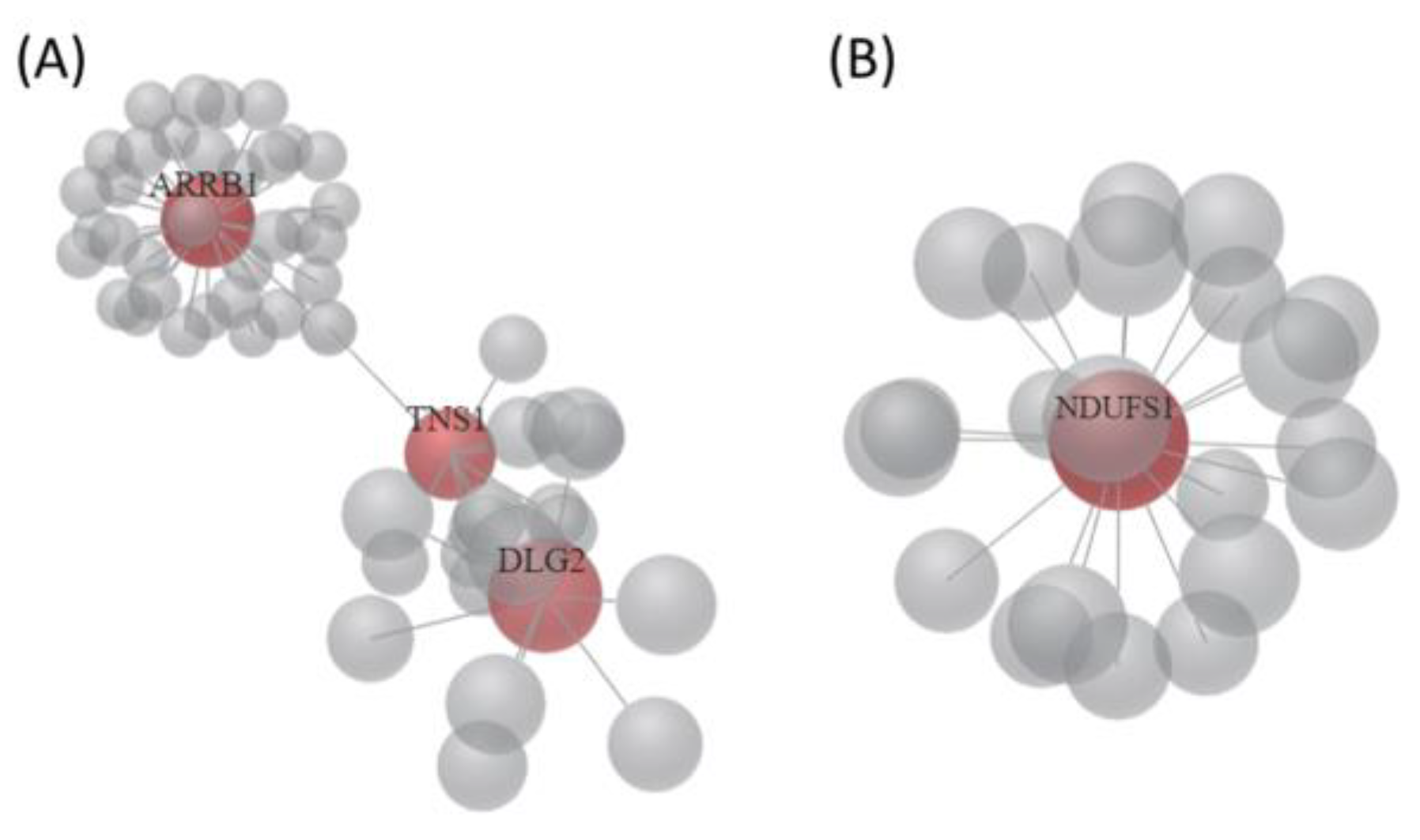

3.5. Identification of Potential miRNA Interactions in EGCG-Treated Bladder TCC Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Comperat, E.M.; Gontero, P.; Mostafid, A.H.; Palou, J.; van Rhijn, B.W.G.; Roupret, M.; Shariat, S.F.; Sylvester, R.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (TaT1 and Carcinoma In Situ)—2019 Update. Eur. Urol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.B.; Chen, K.T.; Guo, H.R. Clinical and epidemiological features of patients with genitourinary tract tumour in a blackfoot disease endemic area of Taiwan. BJU Int. 2008, 102, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfred Witjes, J.; Lebret, T.; Comperat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; De Santis, M.; Bruins, H.M.; Hernandez, V.; Espinos, E.L.; Dunn, J.; Rouanne, M.; et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomer, R.; Sarrats, A.; Lupu, R.; Puig, T. Natural Polyphenols and their Synthetic Analogs as Emerging Anticancer Agents. Curr. Drug Targets 2017, 18, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, A.; Korkmaz, A.; Oter, S.; Coskun, O. Contribution of flavonoid antioxidants to the preventive effect of mesna in cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis in rats. Arch. Toxicol. 2005, 79, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazi, T.; Hajj-Hussein, I.A.; Awwad, J.; Shams, A.; Hijaz, M.; Jurjus, A. A modulating effect of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a tea catechin, on the bladder of rats exposed to water avoidance stress. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2013, 32, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, C.H.; Philips, B.J.; Morrisroe, S.N.; Chancellor, M.B.; Yoshimura, N. Antioxidant effects of green tea and its polyphenols on bladder cells. Life Sci. 2008, 83, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Ho, Y.; Sun, C.; Xia, G.; Ding, Q.; Gu, B. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits the growth and promotes the apoptosis of bladder cancer cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3513–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.W.; Lung, W.Y.; Chun, X.; Luo, X.L.; Huang, W.R. EGCG inhibited bladder cancer T24 and 5637 cell proliferation and migration via PI3K/AKT pathway. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12261–12272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, S.H.; Keck, R.W. A comparative study of the inhibiting effects of mitomycin C and polyphenolic catechins on tumor cell implantation/growth in a rat bladder tumor model. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettlaff, K.; Stawny, M.; Ogrodowczyk, M.; Jelinska, A.; Bednarski, W.; Watrobska-Swietlikowska, D.; Keck, R.W.; Khan, O.A.; Mostafa, I.H.; Jankun, J. Formulation and characterization of EGCG for the treatment of superficial bladder cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, J.R.; Saltzstein, D.R.; Kim, K.; Kolesar, J.; Huang, W.; Havighurst, T.C.; Wollmer, B.W.; Stublaski, J.; Downs, T.; Mukhtar, H.; et al. A Phase II Randomized, Double-blind, Presurgical Trial of Polyphenon E in Bladder Cancer Patients to Evaluate Pharmacodynamics and Bladder Tissue Biomarkers. Cancer Prev Res. 2017, 10, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, M.R.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Rajewsky, N. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J., Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xia, J. OmicsNet: A web-based tool for creation and visual analysis of biological networks in 3D space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W514–W522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang da, W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejnar, C.E.; Zdobnov, E.M. MiRmap: Comprehensive prediction of microRNA target repression strength. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11673–11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; Bell, G.W.; Nam, J.W.; Bartel, D.P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife 2015, 4, e05005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, N.; Wang, X. miRDB: An online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D146–D152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.E.; Sharif, T.; Martell, E.; Dai, C.; Kim, Y.; Lee, P.W.; Gujar, S.A. NAD(+) salvage pathway in cancer metabolism and therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacarelli, T.; Zhang, R. NAD(+) metabolism controls inflammation during senescence. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2019, 6, 1605819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.Z.; Ahn, D.G.; Sharif, T.; Clements, D.; Gujar, S.A.; Lee, P.W. The NAD+ synthesizing enzyme nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 (NMNAT-2) is a p53 downstream target. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kusumanchi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jani, M.B.; Jayaram, N.H.; Khan, R.A.; Tang, Y.; Antony, A.C.; Jayaram, H.N. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase2 overexpression enhances colorectal cancer cell-kill by Tiazofurin. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013, 20, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, H. Decreased NAD Activates STAT3 and Integrin Pathways to Drive Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Mol. Cell Proteom. MCP 2018, 17, 2005–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewska, P.; Gawlik-Jakubczak, T.; Jablonska, P.; Czajkowski, M.; Kutryb-Zajac, B.; Smolenski, R.T.; Matuszewski, M.; Slominska, E.M. Nicotinamide metabolism alterations in bladder cancer: Preliminary studies. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2018, 37, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhu, J.H.; Chen, M.B.; Shen, W.X.; He, J. The association between NQO1 Pro187Ser polymorphism and urinary system cancer susceptibility: A meta-analysis of 22 studies. Cancer Invest. 2015, 33, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Chen, P.; Wilkins, H.M.; Wang, T.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Chen, Q. Pharmacologic ascorbate induces neuroblastoma cell death by hydrogen peroxide mediated DNA damage and reduction in cancer cell glycolysis. Free Radic Biol. Med. 2017, 113, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Ku, J.H. Systemic Inflammatory Response Based on Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Marker in Bladder Cancer. Dis Markers 2016, 2016, 8345286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Lei, L.; Chen, L.; Xie, T.; Li, X. Inflammatory microenvironment in the initiation and progression of bladder cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 93279–93294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Zhang, H.; Qi, R.; Tsao, R.; Mine, Y. Recent Advances in the Understanding of the Health Benefits and Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Green Tea Polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Kao, C.L.; Liu, C.M. The Cancer Prevention, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidation of Bioactive Phytochemicals Targeting the TLR4 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoury, V.; Beland, M.; Schritz, A.; Kim, S.Y.; Nazarov, P.V.; Gaboury, L.; Sertamo, K.; Bernardin, F.; Batutu, R.; Antunes, L.; et al. Identification of beta-arrestin-1 as a diagnostic biomarker in lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tan, S.; Ke, B.; Tao, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.; Wu, B. β-Arrestin1 enhances hepatocellular carcinogenesis through inflammation-mediated Akt signalling. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallifatidis, G.; Smith, D.K.; Morera, D.S.; Gao, J.; Hennig, M.J.; Hoy, J.J.; Pearce, R.F.; Dabke, I.R.; Li, J.; Merseburger, A.S.; et al. β-Arrestins Regulate Stem Cell-Like Phenotype and Response to Chemotherapy in Bladder Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, G.; Ren, S.; Su, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Y. miR-185-3p regulates the invasion and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting WNT2B in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Xie, W.; Li, L.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; He, X. Elevated transgelin/TNS1 expression is a potential biomarker in human colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Liu, H.; Cai, Z.; Dong, W.; Jiang, N.; Yang, M.; Huang, J.; Lin, T. Circ-BPTF promotes bladder cancer progression and recurrence through the miR-31-5p/RAB27A axis. Aging 2018, 10, 1964–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Qin, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhong, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xia, L.; et al. MicroRNA-31 functions as a tumor suppressor and increases sensitivity to mitomycin-C in urothelial bladder cancer by targeting integrin α5. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27445–27457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Zeng, M.; Zhu, H.; Chen, X.; Weng, Z.; Li, S. Emerging role of Hippo signalling pathway in bladder cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Gu, K.; Wang, Q.; Chen, X.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate affects the proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion of tongue squamous cell carcinoma through the hippo-TAZ signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2615–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.W.; Wood, G.A.; Lu, J.; Tang, Q.L.; Liu, J.; Molyneux, S.; Chen, Y.; Fang, H.; Adissu, H.; McKee, T.; et al. Cross-species genomics identifies DLG2 as a tumor suppressor in osteosarcoma. Oncogene 2019, 38, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.J.; Bai, X.X.; Liu, W. MicroRNA-23a depletion promotes apoptosis of ovarian cancer stem cell and inhibits cell migration by targeting DLG2. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | EGCG FPKM | Control FPKM | Fold-Change (EGCG/Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTF2H2C | GTF2H2 family member C | 1.38 | 0.00 | 137677.00 |

| PRRT2 | proline rich transmembrane protein 2 | 21.44 | 0.17 | 126.48 |

| RASA4 | RAS p21 protein activator 4 | 1.81 | 0.17 | 10.92 |

| TMEM92 | transmembrane protein 92 | 1.85 | 0.53 | 3.52 |

| RGPD5 | RANBP2-like and GRIP domain containing 5 | 2.70 | 0.78 | 3.47 |

| SEPT3 | septin 3 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 3.42 |

| MGAT5B | mannosyl (alpha-1,6-)-glycoprotein beta-1,6-N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase, isozyme B | 0.69 | 0.23 | 2.95 |

| GOLGA8B | golgin A8 family member B | 2.59 | 0.93 | 2.79 |

| TSPAN2 | tetraspanin 2 | 2.23 | 0.91 | 2.45 |

| SBNO2 | strawberry notch homolog 2 | 2.08 | 0.91 | 2.28 |

| PPM1K | protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+ dependent 1K | 1.31 | 2.66 | −2.04 |

| FCGRT | Fc fragment of IgG receptor and transporter | 2.05 | 4.95 | −2.41 |

| CDON | cell adhesion associated, oncogene regulated | 0.91 | 2.25 | −2.47 |

| NMNAT2 | nicotinamide nucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 | 1.06 | 3.45 | −3.27 |

| DLG2 | discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 2 | 0.65 | 2.18 | −3.33 |

| ARRB1 | arrestin beta 1 | 0.34 | 1.37 | −4.01 |

| RBPMS | RNA binding protein with multiple splicing | 0.28 | 1.24 | −4.45 |

| TXNDC2 | thioredoxin domain containing 2 | 0.13 | 0.68 | −5.06 |

| TNS1 | tensin 1 | 0.10 | 0.72 | −6.96 |

| GIPR | gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor | 0.51 | 4.77 | −9.44 |

| NDUFS1 | NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S1 | 0.07 | 1.81 | −26.61 |

| KMO | kynurenine 3-monooxygenase | 0.02 | 0.61 | −33.32 |

| Canonical Pathway | p-Value | Overlap | Molecules |

| NAD biosynthesis II | 7.73 × 10−5 | 14.3% | KMO, NMNAT2 |

| NAD biosynthesis III | 5.67 × 10−3 | 16.7% | NMNAT2 |

| NAD biosynthesis from 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate semialdehyde | 6.62 × 10−3 | 14.3% | KMO |

| Thioredoxin pathway | 6.62 × 10−3 | 14.3% | TXNDC2 |

| NAD salvage pathway III | 6.62 × 10−3 | 14.3% | NMNAT2 |

| Diseases and Disorders | p-Value Range | Number of Molecules | |

| Inflammatory response | 3.36 × 10−2 to 1.86 × 10−4 | 8 | TSPAN2, TNS1, MGAT5B, SBNO2, GIPR, FCGRT, ARRB1, KMO |

| Cancer | 4.54 × 10−2 to 2.86 × 10−4 | 21 | |

| Organismal injury and abnormalities | 4.54 × 10−2 to 2.86 × 10−4 | 21 | |

| Reproductive system disease | 1.49 × 10−2 to 6.33 × 10−4 | 15 | |

| Dermatological diseases and conditions | 2.62 × 10−2 to 8.26 × 10−4 | 14 |

| Top Diseases and Functions | Score | Focus Molecules | Molecules in Network | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nervous System Development and Function, Tissue Morphology, Neurological Disease | 24 | 10 | APP, ↓ARRB1, Akt, ↓CDON, Cytochrome bc1, ECE2, ↓GIPR, HNRNPL, Jnk, MYC, NDUFB8, ↓NDUFS1, NDUFS4, NEDD4, NFATC2, ↓NMNAT2, NTRK1, Nedd4, ↓PPM1K, ↑RASA4, ↑RGPD5, ↑TMEM92, ↑TSPAN2, Trhr2, XPO1, miR-1229-3p, miR-27a-3p, miR-3691-5p, miR-376b-5p, miR-4435, miR-4752, miR-550b-3p, miR-6811-3p, miR-8056, quinolinic acid |

| 2 | Inflammatory Response, Antimicrobial Response, Cellular Development | 24 | 10 | CDH1, ↓DLG2, EP300, F2RL1, ↓FCGRT, GOLGA8A/↑GOLGA8B, ↑GTF2H2C, GTF2H2C_2, Holo RNA polymerase II, IFNG, IL6, ↓KMO, MDM2, NFATC2, ↑PRRT2, ↑SBNO2, ↑SEPT3, SRC, ↓TNS1, ↓TXNDC2, XPO1, miR-103b, miR-1243, miR-1281, miR-1307-3p, miR-20a-3p, miR-217-5p, miR-3060-5p, miR-3187-3p, miR-4638-5p, miR-4684-3p, miR-4707-3p, miR-4743-3p, miR-499b-5p, miR-924 |

| 3 | Connective Tissue Development and Function, Embryonic Development, Organismal Development | 4 | 2 | CAMK2B, CREB5, DMRT3, FNDC11, HOXA1, KRTAP12-2, KRTAP19-5, ↑MGAT5B, OTX1, PITX1, ↓RBPMS, TRIP13, miR-1285-3p, miR-3473b, miR-4749-3p, miR-485-5p, miR-6132, miR-6850-3p, miR-744-5p |

| Canonical Pathway | p-Value | Overlap | Molecules |

| NAD biosynthesis II | 1.77 × 10−3 | 14.3% | KMO, NMNAT2 |

| Hippo signaling | 6.74 × 10−3 | 3.5% | DLG2, SCRIB, SMAD1 |

| Dopamine degradation | 8.08 × 10−3 | 6.7% | ALDH1A1, SULT1A3 |

| Spliceosomal cycle | 9.01 × 10−3 | 50.0% | U2AF1 |

| Asparagine degradation I | 9.01 × 10−3 | 50.0% | ASPG |

| Diseases and Disorders | p-Value Range | Number of Molecules | |

| Cancer | 4.86 × 10−2 to 1.12 × 10−4 | 94 | |

| Organismal injury and abnormalities | 4.86 × 10−2 to 1.12 × 10−4 | 96 | |

| Infectious diseases | 4.42 × 10−2 to 1.08 × 10−3 | 3 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4.42 × 10−2 to 1.62 × 10−3 | 13 | |

| Hereditary disorder | 4.42 × 10−2 to 1.62 × 10−3 | 25 |

| Biological Process | Genes | p Value | Fold Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation-reduction process | P3H2, ALDH1A1, PXDN, TXNDC2, PYROXD2, NCF1, KMO, SDR9C7, PRODH | 0.0108 | 2.934 |

| Positive regulation of IκB kinase/NFκB signaling | CD36, EEF1D, GPR89A, S100A12 | 0.0497 | 4.795 |

| NAD metabolic process | NMNAT2, KMO | 0.0549 | 35.093 |

| xenobiotic metabolic process | NAT1, SULT1A3, S100A12 | 0.0606 | 7424 |

| carboxylic acid metabolic process | GAD1, PDXDC1 | 0.0646 | 29.694 |

| response to fatty acid | CD36, GIPR | 0.0836 | 22.707 |

| superoxide metabolic process | IMMP2L, NCF1 | 0.0976 | 19.301 |

| KEGG pathway | Genes | p value | Fold Enrichment |

| Metabolic pathways | ALDH1A1, NMNAT2, MGAT5B, NAT1, KMO, PLCD1, ITPK1, GAD1, POLR2J2, NDUFS1, PRODH | 0.0651 | 1.774 |

| Putative mRNA | mRNA Fold Change (EGCG/Ctrl) | Predicted miRNA | miRNA Fold Change (EGCG/Ctrl) | miRmap Score | TargetScan | miRDB | Seed Region of 3′UTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARRB1 | −4.01 | hsa-miR-185-3p | 3.92 | 98.87 | Yes | Yes | 815–821, 1723–1729 |

| ARRB1 | −4.01 | hsa-miR-3139 | 2.88 | 98.04 | Yes | No | |

| RBPMS | −4.45 | hsa-miR-3176 | 2.17 | 97.23 | Yes | No | |

| MGAT5B | 2.95 | hsa-miR-3116 | −4.65 | 98.69 | Yes | Yes | 201–207, 492–499, 537–543, 1263–1270 |

| MGAT5B | 2.95 | hsa-miR-6724-5p | −3.96 | 99.88 | Yes | No | |

| NDUFS1 | −26.61 | hsa-miR-1285-3p | 3.43 | 97.99 | Yes | No | |

| TNS1 | −6.96 | hsa-miR-1285-3p | 3.43 | 98.55 | Yes | No | |

| TNS1 | −6.96 | hsa-miR-18a-3p | 3.13 | 99.36 | Yes | No | |

| TNS1 | −6.96 | hsa-miR-31-5p | 2.14 | 97.84 | Yes | Yes | 2786–2793, 4195–4202 |

| TNS1 | −6.96 | hsa-miR-3176 | 2.17 | 99.13 | Yes | No | |

| TNS1 | −6.96 | hsa-miR-642a-5p | 8.27 | 99.85 | Yes | Yes | 137–144, 3071–3077, 3157–3164, 3437–3443, 4219–4225 |

| DLG2 | −3.33 | hsa-miR-1226-3p | 2.28 | 99.63 | Yes | Yes | 3812–3819, 3825–3831, 3846–3853 |

| DLG2 | −3.33 | hsa-miR-484 | 2.68 | 80.73 | Yes | Yes | 1104–1110 |

| NMNAT2 | −3.27 | hsa-miR-185-3p | 3.92 | 98.12 | Yes | No | |

| NMNAT2 | −3.27 | hsa-miR-93-3p | 2.64 | 97.35 | Yes | No | |

| KMO | −33.32 | hsa-miR-18a-3p | 3.13 | 97.34 | Yes | No | |

| PPM1K | −2.04 | hsa-miR-22-3p | 2.04 | 97.03 | Yes | Yes | 299–306 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chang, W.-A.; Li, W.-M.; Ke, H.-L.; Wu, W.-J.; Kuo, P.-L. Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma―Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Approaches. Medicina 2019, 55, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120768

Lee H-Y, Chen Y-J, Chang W-A, Li W-M, Ke H-L, Wu W-J, Kuo P-L. Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma―Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Approaches. Medicina. 2019; 55(12):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120768

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hsiang-Ying, Yi-Jen Chen, Wei-An Chang, Wei-Ming Li, Hung-Lung Ke, Wen-Jeng Wu, and Po-Lin Kuo. 2019. "Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma―Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Approaches" Medicina 55, no. 12: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120768

APA StyleLee, H.-Y., Chen, Y.-J., Chang, W.-A., Li, W.-M., Ke, H.-L., Wu, W.-J., & Kuo, P.-L. (2019). Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Urinary Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma―Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics Approaches. Medicina, 55(12), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55120768