Dihydromyricetin Remodels the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.2. Data Preprocessing and Standardization

2.3. DHM-Related Target Acquisition

2.4. HCC Differential Gene Screening

2.5. Prognostic Gene Modeling

2.6. Construction of Nomogram

2.7. Immune Infiltration Analysis

2.8. Drug Sensitivity Analysis

2.9. Molecular Docking

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening for DHM-Associated Genes Relevant to Prognosis

3.2. Construction and Evaluation of Prognostic Models Based on DHM-Related Targets

3.3. Survival Analysis and Nomogram Construction

3.4. Validation of Prognostic Model for DHMGs

3.5. Nomogram Construction

3.6. Immunization Landscapes of Different Risk Groups

3.6.1. Immune Cell Infiltration

3.6.2. The Seven Steps of the Anti-Tumor Immune Cycle

3.6.3. Immune-Related Molecules

3.6.4. Immune-Related Scores

3.6.5. Immunization Landscapes of Validation Dataset

3.7. Drug Sensitivity Analysis

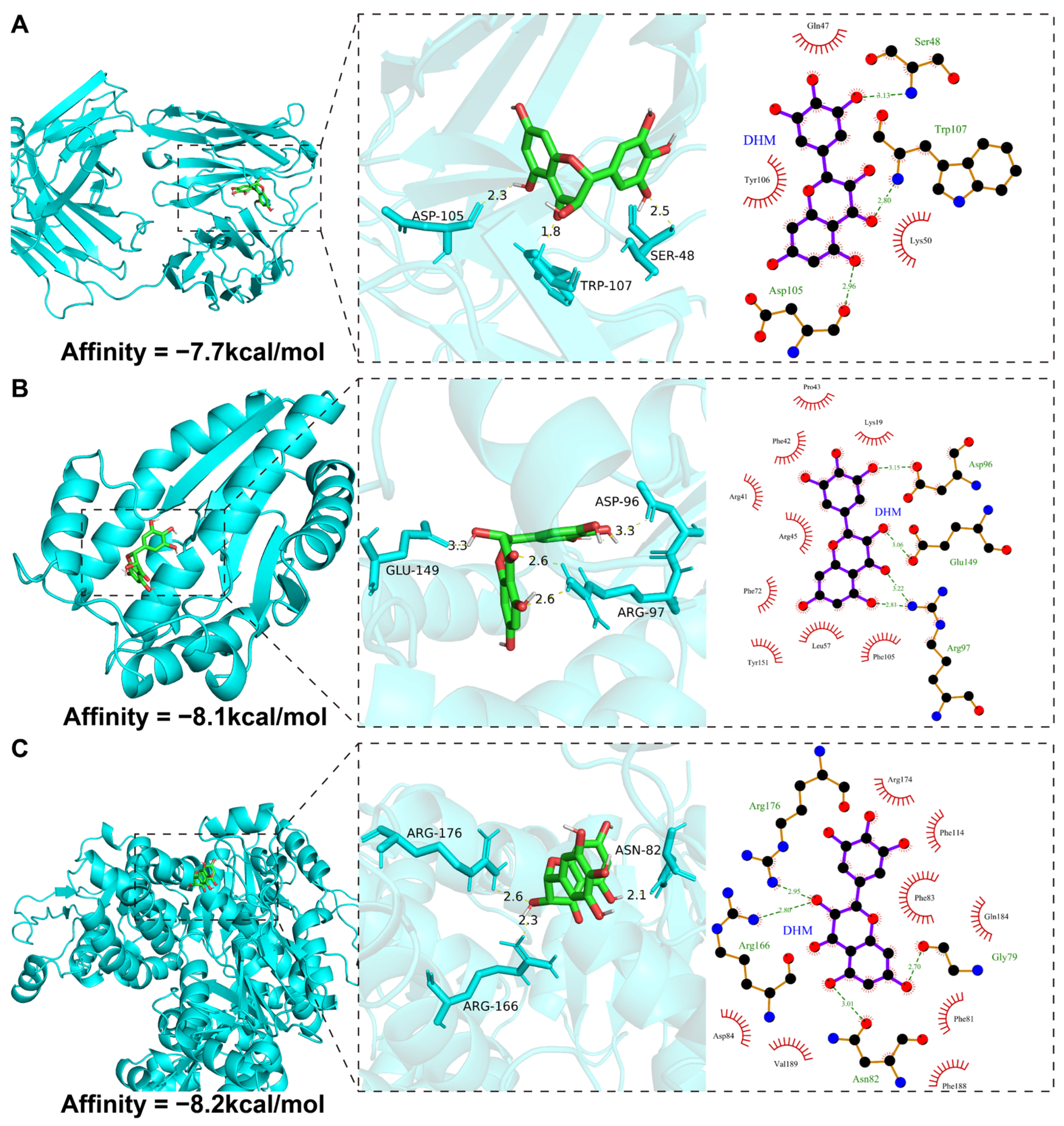

3.8. Molecular Docking Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| DHM | Dihydromyricetin |

| DHMGs | 7 DHM-related genes |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GDSC | The Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GSVA | Gene Set Variation Analysis |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage And Selection Operator |

| MSI Expr Sig | Microsatellite Instability Expression Signature |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| RNA-Seq | RNA sequencing |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SMILES | Simplified molecular input line entry system |

| SRGs | Sorafenib Resistance Genes |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas Program |

| TIDE | Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion |

| TIP | Tracking Tumor Immunophenotype |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Geng, H.; Zhu, A.X.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Fan, J.; Wang, C.; Gao, Q. Precision treatment in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, A.X.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Wang, C. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, S.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Ai, Q.; et al. Mechanism of Dihydromyricetin on Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 794563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhu, M.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Hu, L.; Jing, W.; Lu, H.; Wang, S. Dihydromyricetin improves DSS-induced colitis in mice via modulation of fecal-bacteria-related bile acid metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 171, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Peng, L.; Tian, X.; Qiu, X.; Cao, H.; Yang, Q.; Liao, R.; Yan, F. Dihydromyricetin protects HUVECs of oxidative damage induced by sodium nitroprusside through activating PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a signalling pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4829–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, Y.N.; Gu, J.; He, P.; Ai, Q.D.; Zhou, X.D.; Wang, W.; Qin, L. Mechanisms of dihydromyricetin against hepatocellular carcinoma elucidated by network pharmacology combined with experimental validation. Pharm. Biol. 2023, 61, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Yu, X.; Moradian, R.; Folk, C.; Spatz, M.H.; Kim, P.; Bhatti, A.A.; Davies, D.L.; Liang, J. Dihydromyricetin Protects the Liver via Changes in Lipid Metabolism and Enhanced Ethanol Metabolism. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 44, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ye, W.C.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Dai, W.; Li, M. Anticancer effects of dihydromyricetin on the proliferation, migration, apoptosis and in vivo tumorigenicity of human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.J.; He, Y.F.; Yuan, W.Z.; Xiang, L.J.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.R.; Duan, J.; He, Y.H.; Li, M.Y. Dihydromyricetin-mediated inhibition of the Notch1 pathway induces apoptosis in QGY7701 and HepG2 hepatoma cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6242–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, K.; Czerwińska, P.; Wiznerowicz, M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): An immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol. 2015, 19, A68–A77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Miao, Y.; Deng, K.; Yang, F.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; You, R.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; et al. HCCDB v2.0: Decompose Expression Variations by Single-cell RNA-seq and Spatial Transcriptomics in HCC. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2024, 22, qzae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinyol, R.; Montal, R.; Bassaganyas, L.; Sia, D.; Takayama, T.; Chau, G.Y.; Mazzaferro, V.; Roayaie, S.; Lee, H.C.; Kokudo, N.; et al. Molecular predictors of prevention of recurrence in HCC with sorafenib as adjuvant treatment and prognostic factors in the phase 3 STORM trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan-Fendt, K.; Li, D.; Reyes, R.; Yu, L.; Wani, N.A.; Hu, P.; Jacob, S.T.; Ghoshal, K.; Payne, P.R.O.; Motiwala, T. Transcriptomics-Based Drug Repurposing Approach Identifies Novel Drugs against Sorafenib-Resistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Lai, L.; Pei, J.; Li, H. PharmMapper 2017 update: A web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W356–W360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, U. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Deng, C.; Pang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Liao, G.; Yuan, H.; Cheng, P.; Li, F.; Long, Z.; et al. TIP: A Web Server for Resolving Tumor Immunophenotype Profiling. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 6575–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, B.; Wong, C.N.; Tong, Y.; Zhong, J.Y.; Zhong, S.S.W.; Wu, W.C.; Chu, K.C.; Wong, C.Y.; Lau, C.Y.; Chen, I.; et al. TISIDB: An integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4200–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Classification of triple-negative breast cancers based on Immunogenomic profiling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Gu, S.; Pan, D.; Fu, J.; Sahu, A.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Traugh, N.; Bu, X.; Li, B.; et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Soares, J.; Greninger, P.; Edelman, E.J.; Lightfoot, H.; Forbes, S.; Bindal, N.; Beare, D.; Smith, J.A.; Thompson, I.R.; et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): A resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D955–D961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Adegboro, A.A.; Fasoranti, D.O.; Dai, L.; Pan, Z.; Liu, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Mime: A flexible machine-learning framework to construct and visualize models for clinical characteristics prediction and feature selection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2798–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhatt, R.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Biester, A.; Biswas, P.; Bittrich, S.; Blaumann, S.; Brown, R.; Chao, H.; et al. Updated resources for exploring experimentally-determined PDB structures and Computed Structure Models at the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D564–D574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, S.; Bordoloi, M. Molecular Docking: Challenges, Advances and its Use in Drug Discovery Perspective. Curr. Drug Targets 2019, 20, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhou, M. Analysis of the role of dihydromyricetin derived from vine tea (Ampelopsis grossedentata) on multiple myeloma by activating STAT1/RIG-I axis. Oncol. Res. 2024, 32, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, K.J.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Tian, X.D.; Wang, B. Inhibition of human lung cancer proliferation through targeting stromal fibroblasts by dihydromyricetin. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 9758–9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X. Semaphoring 4D is required for the induction of antioxidant stress and anti-inflammatory effects of dihydromyricetin in colon cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 67, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, M.; Yang, Q.; Ouyang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, W. Ampelopsin induces MDA-MB-231 cell cycle arrest through cyclin B1-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharm. 2023, 73, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Z.S.; Cai, W.W.; Deng, Y.; Chen, L.; Tan, S.L. Dihydromyricetin Inhibits Tumor Growth and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through regulating miR-455-3p in Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 6058–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, Y.; Gong, T.; Pan, Q.; Xiang, T.; Zhao, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, H.; Han, Y.; Song, M.; et al. Inhibition of DTYMK significantly restrains the growth of HCC and increases sensitivity to oxaliplatin. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hao, Z.; He, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Shu, X.; Sun, B.; Hu, Z.; Hu, S.; Hou, X.; et al. Accumulation of microtubule-associated protein tau promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis through inhibiting autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 3621–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, N.; Zhou, B.; Hou, G.; Xi, Z.; Wang, W.; Yan, M.; He, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The protection of UCK2 protein stability by GART maintains pyrimidine salvage synthesis for HCC growth under glucose limitation. Oncogene 2025, 44, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Shan, Y.; Tan, H. Rabdosia rubescens (Hemsl.) H. Hara: A potent anti-tumor herbal remedy—Botany, phytochemistry, and clinical applications and insights. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 340, 119200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Shan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Tan, H. Polysaccharides from Lonicera japonica Thunb.: Extraction, purification, structural features and biological activities—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, J.; Gu, C.; Huo, R.; Ding, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; et al. Juglone induces ferroptotic effect on hepatocellular carcinoma and pan-cancer via the FOSL1-HMOX1 axis. Phytomedicine 2025, 139, 156417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mao, Y.; Ding, L.; Zeng, X.A. Dihydromyricetin: A review on identification and quantification methods, biological activities, chemical stability, metabolism and approaches to enhance its bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Lin, X.H.; Guo, H.Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, D.Y.; Sun, J.L.; Zhang, G.C.; Xu, R.C.; Wang, F.; Yu, X.N.; et al. Multi-Omics profiling identifies aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 as a critical mediator in the crosstalk between Treg-mediated immunosuppression microenvironment and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 2763–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finotello, F.; Trajanoski, Z. New strategies for cancer immunotherapy: Targeting regulatory T cells. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Wei, X.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, X. Zn-DHM nanozymes regulate metabolic and immune homeostasis for early diabetic wound therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 49, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K.; Tang, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y. Regulation of Concanavalin A-induced Immune Hepatitis in Mice by Dihydromyricetin at the M1/M2 Type Macrophage Level. Discov. Med. 2025, 37, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, H.; Ma, S.; Lu, C.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Li, M.; Zhu, R. Dihydromyricetin Enhances the Chemo-Sensitivity of Nedaplatin via Regulation of the p53/Bcl-2 Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.H.; Lang, H.D.; Wang, X.L.; Hui, S.C.; Zhou, M.; Kang, C.; Yi, L.; Mi, M.T.; Zhang, Y. Synergy between dihydromyricetin intervention and irinotecan chemotherapy delays the progression of colon cancer in mouse models. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Azami, N.L.B.; Sun, M.; Li, Q. Dihydromyricetin reverses MRP2-induced multidrug resistance by preventing NF-κB-Nrf2 signaling in colorectal cancer cell. Phytomedicine 2021, 82, 153414, Erratum in Phytomedicine 2022, 100, 153732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Sui, H.; Ji, Q.; E, Q.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Dihydromyricetin reverses MRP2-mediated MDR and enhances anticancer activity induced by oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2017, 28, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Yan, T.; Liu, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, H.; Jiang, S. Link of sorafenib resistance with the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanistic insights. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 991052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C. Salt Cocrystallization—A Method to Improve Solubility and Bioavailability of Dihydromyricetin. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Mean | Std | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTYMK | 33.960534 | 23.7597 | 0.0439839051614121 |

| MAPT | 1.609325 | 9.508439 | 0.024687244385511 |

| UCK2 | 9.508439 | 7.874771 | 0.134099098314701 |

| Characteristic | High Risk | Low Risk | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 115 | 114 | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.262 | ||

| <60 | 65 (56.5%) | 55 (48.2%) | |

| <60 | 50 (43.5%) | 59 (51.8%) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.505 | ||

| Female | 39 (33.9%) | 33 (28.9%) | |

| Male | 76 (66.1%) | 81 (71.1%) | |

| T stage, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| T1–2 | 75 (65.2%) | 90 (78.9%) | |

| T3–4 | 40 (34.8%) | 24 (21.1%) | |

| N stage, n (%) | 0.622 | ||

| N0 | 112 (97.4%) | 113 (99.1%) | |

| N1 | 3 (2.61%) | 1 (0.88%) | |

| M stage, n (%) | 0.622 | ||

| M0 | 114 (99.1%) | 112 (98.2%) | |

| M1 | 1 (0.87%) | 2 (1.75%) | |

| Stage, n (%) | 0.023 | ||

| Stage I–II | 73 (63.5%) | 89 (78.1%) | |

| Stage III–IV | 42 (36.5%) | 25 (21.9%) | |

| Grade, n (%) | 0.003 | ||

| G1–2 | 53 (46.1%) | 76 (66.7%) | |

| G3–4 | 62 (53.9%) | 38 (33.3%) | |

| Status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Alive | 64 (55.7%) | 92 (80.7%) | |

| Dead | 51 (44.3%) | 22 (19.3%) |

| Characteristic | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | FDR | HR (95%CI) | FDR | |

| Age (<60 vs. ≥ 60) | 1.206 (0.761–1.911) | 0.4863 | ||

| Gender (FEMALE vs. MALE) | 0.750 (0.468–1.204) | 0.3745 | ||

| Grade (G1–2 vs. G3–4) | 1.073 (0.675–1.704) | 0.7666 | ||

| Stage (stage I–II vs. stage III–IV) | 2.974 (1.874–4.720) | <0.001 | 1.354 (0.184–9.947) | 0.7659 |

| T stage (T1–2 vs. T3–4) | 2.991 (1.884–4.749) | <0.001 | 1.707 (0.231–12.618) | 0.7659 |

| N stage (N0 vs. N1) | 2.123 (0.518–8.695) | 0.3937 | ||

| M stage (M0 vs. M1) | 4.055 (1.270–12.947) | 0.0363 | 2.890 (0.866–9.644) | 0.1688 |

| Risk score | 57.037 (16.725–194.506) | <0.001 | 41.050 (11.493–146.614) | <0.001 |

| Target | PDB ID | Refinement Resolution (Å) | Affinity (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTYMK | 1NN0 | 1.60 | −8.1 |

| MAPT | 6PXR | 1.556 | −7.7 |

| UCK2 | 7SQL | 2.40 | −8.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Gu, C.; Li, W.; Lan, F.; Mao, J.; Tan, X.; Li, P. Dihydromyricetin Remodels the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121010

Xu Y, Gu C, Li W, Lan F, Mao J, Tan X, Li P. Dihydromyricetin Remodels the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121010

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yang, Chao Gu, Wei Li, Fei Lan, Jingkun Mao, Xiao Tan, and Pengfei Li. 2025. "Dihydromyricetin Remodels the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121010

APA StyleXu, Y., Gu, C., Li, W., Lan, F., Mao, J., Tan, X., & Li, P. (2025). Dihydromyricetin Remodels the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Model. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121010