Western Diet Induces Changes in Gene Expression in Multiple Tissues During Early Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in Male C57BL/6 Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Diet

2.2. RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

2.3. Statistical Analysis

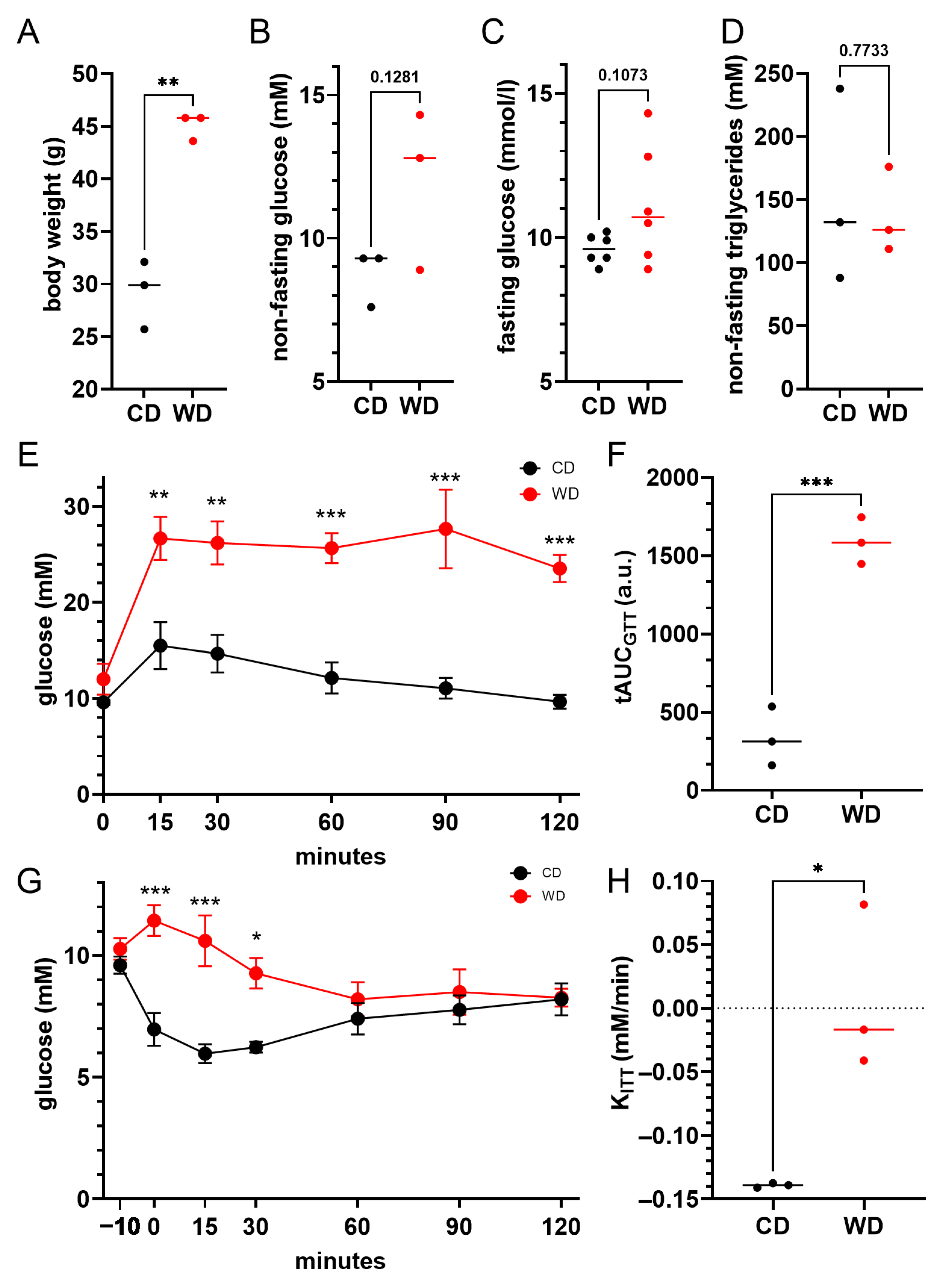

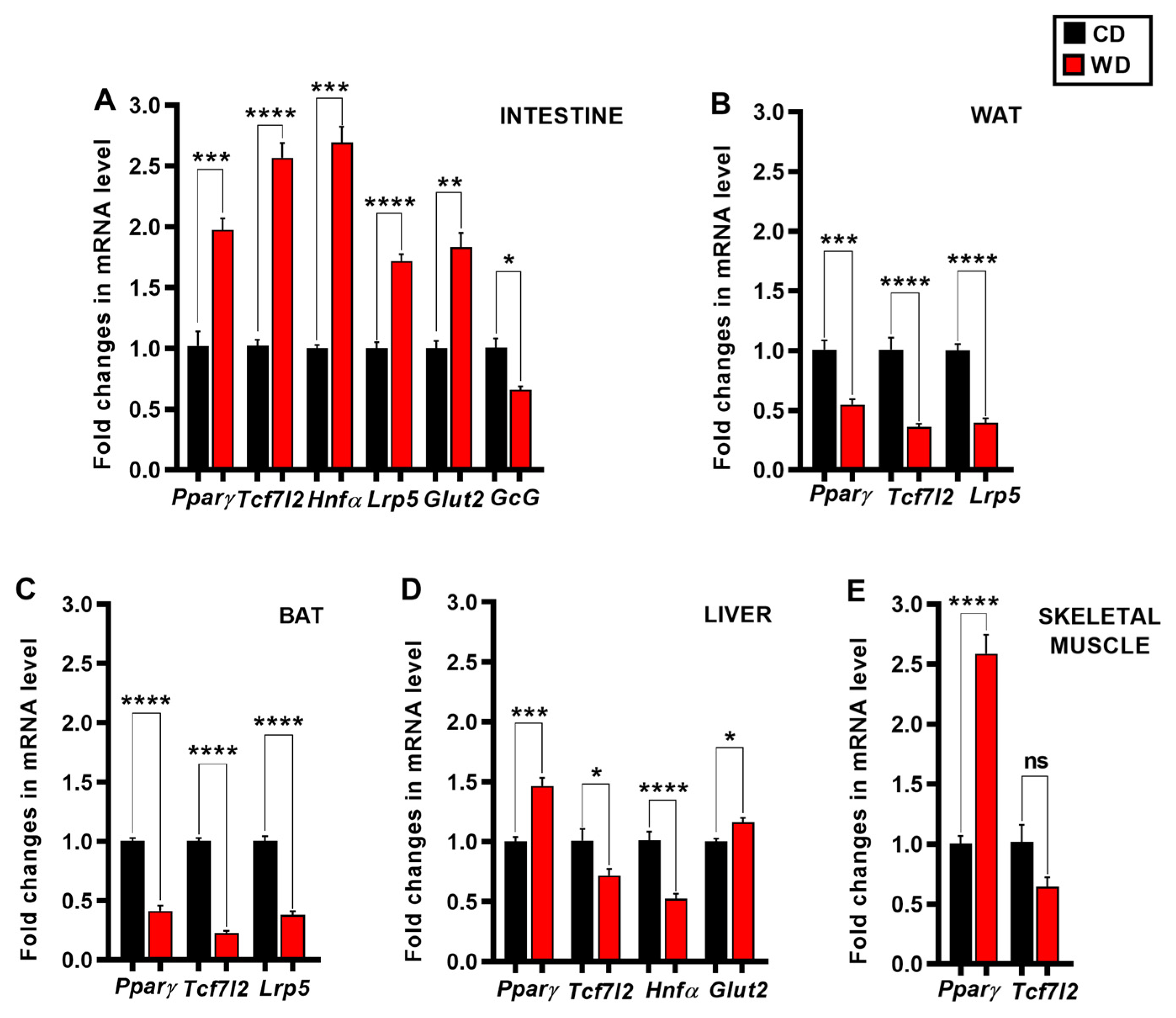

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| β2M | Beta 2 microglobulin |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| CD | Control diet |

| cDNA | Complementary Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| c-Myc | Myc myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| Ct | Cycle threshold value |

| FFAs | Free fatty acids |

| GcG | Glucagon |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| Glut2 | Glucose transporter 2 |

| GSIS | Glucose stimulated insulin secretion |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| Hnf-1α | Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| Ins2 | Insulin 2 |

| ipITT | Intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test |

| ipGTT | Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| IS | Insulin sensitivity |

| Lrp5 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 |

| MafA | MAF bZIP transcription factor A |

| MafB | MAF bZIP transcription factor B |

| MODY3 | Maturity-onset diabetes of the young 3 |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic acid |

| Ngn3 | Neurogenin 3 |

| Nkx2.2 | NK2 Homeobox 2 |

| NOD | Non obese diabetic |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| Pdx1 | Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 |

| PGC-1α | PPARγ coactivator-1 alpha |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma |

| RT-qPCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| SEM | The standard error of the mean |

| Slc2a2 | Solute carrier family 2 member 2 (Glut2) |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| Sox9 | SRY (Sex determining region Y)-box 9 |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| Tcf7L2 | T cell-specific transcription factor 7-like 2 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| WD | Western diet |

| Wnt | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family |

References

- Stozer, A.; Hojs, R.; Dolensek, J. Beta Cell Functional Adaptation and Dysfunction in Insulin Resistance and the Role of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron 2019, 143, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zuurmond, M.G.; van der Schaft, N.; Nano, J.; Wijnhoven, H.A.H.; Ikram, M.A.; Franco, O.H.; Voortman, T. Plant versus animal based diets and insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R.S.; Feresin, R.G. Plant-Based Diets in the Reduction of Body Fat: Physiological Effects and Biochemical Insights. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Liu, G.; Hu, F.B.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Sun, Q. Association Between Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Scott, D.; Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; Giles, G.G.; Ebeling, P.R.; Sanders, K.M. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Chen, C.; He, F.; Ye, Y.; Bai, X.; Cai, L.; Xia, M. Association between dietary protein intake and type 2 diabetes varies by dietary pattern. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigrezaei, S.; Ghiasvand, R.; Feizi, A.; Iraj, B. Relationship between Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rines, A.K.; Sharabi, K.; Tavares, C.D.; Puigserver, P. Targeting hepatic glucose metabolism in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, J.; Carvou, N.J.; Debnam, E.S.; Srai, S.K.; Unwin, R.J. Diabetes increases facilitative glucose uptake and GLUT2 expression at the rat proximal tubule brush border membrane. J. Physiol. 2003, 553, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.Q.; Debreceni, T.L.; Bambrick, J.E.; Chia, B.; Wishart, J.; Deane, A.M.; Rayner, C.K.; Horowitz, M.; Young, R.L. Accelerated intestinal glucose absorption in morbidly obese humans: Relationship to glucose transporters, incretin hormones, and glycemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheele, C.; Nielsen, S. Metabolic regulation and the anti-obesity perspectives of human brown fat. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, B.T.; Suchacki, K.J.; Stimson, R.H. Mechanisms in endocrinology: Human brown adipose tissue as a therapeutic target: Warming up or cooling down? Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 184, R243–R259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliszewska, K.; Kretowski, A. Brown Adipose Tissue and Its Role in Insulin and Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarelli, A.; Genchi, V.A.; Perrini, S.; Natalicchio, A.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F. Insulin and Insulin Receptors in Adipose Tissue Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, G.; Chen, X.; Ruiz, J.; White, J.V.; Rossetti, L. Mechanisms of fatty acid-induced inhibition of glucose uptake. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, J.; Neumann-Haefelin, C.; Belz, U.; Kalisch, J.; Juretschke, H.P.; Stein, M.; Kleinschmidt, E.; Kramer, W.; Herling, A.W. Intramyocellular lipid and insulin resistance: A longitudinal in vivo 1H-spectroscopic study in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes 2003, 52, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 2005, 365, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.R.; Nachbar, R.T.; Gorjao, R.; Vinolo, M.A.; Festuccia, W.T.; Lambertucci, R.H.; Cury-Boaventura, M.F.; Silveira, L.R.; Curi, R.; Hirabara, S.M. Mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle insulin resistance induced by fatty acids: Importance of the mitochondrial function. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: Integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, M.; Peschard, S.; Lestavel, S.; Staels, B. Intestine-liver crosstalk in Type 2 Diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 2021, 123, 154844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas-Boas, E.A.; Almeida, D.C.; Roma, L.P.; Ortis, F.; Carpinelli, A.R. Lipotoxicity and beta-Cell Failure in Type 2 Diabetes: Oxidative Stress Linked to NADPH Oxidase and ER Stress. Cells 2021, 10, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.G.; Shaw, J.A.; Taylor, R. Type 2 Diabetes: The Pathologic Basis of Reversible beta-Cell Dysfunction. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, D.Q.; Bussen, M.; Sehayek, E.; Ananthanarayanan, M.; Shneider, B.L.; Suchy, F.J.; Shefer, S.; Bollileni, J.S.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Breslow, J.L.; et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha is an essential regulator of bile acid and plasma cholesterol metabolism. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonzo, J.A.; Patterson, A.D.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.J. Metabolomics identifies novel Hnf1alpha-dependent physiological pathways in vivo. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.; Chiang, Y.T.; Jin, T. The involvement of the wnt signaling pathway and TCF7L2 in diabetes mellitus: The current understanding, dispute, and perspective. Cell Biosci. 2012, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, J. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling and Obesity. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.H.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, N.J.; Yang, Z.; Tao, X.M.; Du, Y.P.; Wang, X.C.; Lu, B.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Hu, R.M.; et al. TCF7L2 regulates pancreatic beta-cell function through PI3K/AKT signal pathway. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Suh, J.M.; Hah, N.; Liddle, C.; Atkins, A.R.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. PPARgamma signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernysheva, M.B.; Ruchko, E.S.; Karimova, M.V.; Vorotelyak, E.A.; Vasiliev, A.V. Development, regeneration, and physiological expansion of functional beta-cells: Cellular sources and regulators. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1424278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Chen, H.; Xue, J.; Li, P.; Fu, X. The role of GLUT2 in glucose metabolism in multiple organs and tissues. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6963–6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.M. Variation in the Evolution and Sequences of Proglucagon and the Receptors for Proglucagon-Derived Peptides in Mammals. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 700066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei, A.F. LRP5: A Multifaceted Co-Receptor in Development, Disease, and Therapeutic Target. Cells 2025, 14, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T. Current Understanding on Role of the Wnt Signaling Pathway Effector TCF7L2 in Glucose Homeostasis. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servitja, J.M.; Pignatelli, M.; Maestro, M.A.; Cardalda, C.; Boj, S.F.; Lozano, J.; Blanco, E.; Lafuente, A.; McCarthy, M.I.; Sumoy, L.; et al. Hnf1alpha (MODY3) controls tissue-specific transcriptional programs and exerts opposed effects on cell growth in pancreatic islets and liver. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2945–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefterova, M.I.; Haakonsson, A.K.; Lazar, M.A.; Mandrup, S. PPARgamma and the global map of adipogenesis and beyond. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luquero, A.; Pimentel, N.; Vilahur, G.; Badimon, L.; Borrell-Pages, M. Reduced Growth and Inflammation in Lrp5(-/-) Mice Adipose Tissue. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorens, B. GLUT2, glucose sensing and glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybutt, D.R.; Weir, G.C.; Kaneto, H.; Lebet, J.; Palmiter, R.D.; Sharma, A.; Bonner-Weir, S. Overexpression of c-Myc in beta-cells of transgenic mice causes proliferation and apoptosis, downregulation of insulin gene expression, and diabetes. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensellam, M.; Jonas, J.C.; Laybutt, D.R. Mechanisms of beta-cell dedifferentiation in diabetes: Recent findings and future research directions. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R109–R143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, P.A.; Freude, K.K.; Tran, M.N.; Mayes, E.E.; Jensen, J.; Kist, R.; Scherer, G.; Sander, M. SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1865–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, C.C.; Aranias, T.; Viel, T.; Chateau, D.; Le Gall, M.; Waligora-Dupriet, A.J.; Melchior, C.; Rouxel, O.; Kapel, N.; Gourcerol, G.; et al. Intestinal invalidation of the glucose transporter GLUT2 delays tissue distribution of glucose and reveals an unexpected role in gut homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuit, F.C.; Huypens, P.; Heimberg, H.; Pipeleers, D.G. Glucose sensing in pancreatic beta-cells: A model for the study of other glucose-regulated cells in gut, pancreas, and hypothalamus. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueckler, M.; Thorens, B. The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wemelle, E.; Carneiro, L.; Abot, A.; Lesage, J.; Cani, P.D.; Knauf, C. Glucose Stimulates Gut Motility in Fasted and Fed Conditions: Potential Involvement of a Nitric Oxide Pathway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.; Wood, I.S.; Palejwala, A.; Ellis, A.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. Expression of monosaccharide transporters in intestine of diabetic humans. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002, 282, G241–G248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencurel, F.; Waeber, G.; Antoine, B.; Rocchiccioli, F.; Maulard, P.; Girard, J.; Leturque, A. Requirement of glucose metabolism for regulation of glucose transporter type 2 (GLUT2) gene expression in liver. Biochem. J. 1996, 314, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Guerra, S.; Lupi, R.; Marselli, L.; Masini, M.; Bugliani, M.; Sbrana, S.; Torri, S.; Pollera, M.; Boggi, U.; Mosca, F.; et al. Functional and molecular defects of pancreatic islets in human type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005, 54, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrizas, M.; Maestro, M.A.; Boj, S.F.; Paniagua, A.; Casamitjana, R.; Gomis, R.; Rivera, F.; Ferrer, J. Hepatic nuclear factor 1-alpha directs nucleosomal hyperacetylation to its tissue-specific transcriptional targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 3234–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, D.Q.; Screenan, S.; Munoz, K.N.; Philipson, L.; Pontoglio, M.; Yaniv, M.; Polonsky, K.S.; Stoffel, M. Loss of HNF-1alpha function in mice leads to abnormal expression of genes involved in pancreatic islet development and metabolism. Diabetes 2001, 50, 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.; Yamada, Y.; Someya, Y.; Miyawaki, K.; Ihara, Y.; Hosokawa, M.; Toyokuni, S.; Tsuda, K.; Seino, Y. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha recruits the transcriptional co-activator p300 on the GLUT2 gene promoter. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luco, R.F.; Maestro, M.A.; del Pozo, N.; Philbrick, W.M.; de la Ossa, P.P.; Ferrer, J. A conditional model reveals that induction of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha in Hnf1alpha-null mutant beta-cells can activate silenced genes postnatally, whereas overexpression is deleterious. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Jimenez, C.; Garcia-Martinez, J.M.; Chocarro-Calvo, A.; De la Vieja, A. A new link between diabetes and cancer: Enhanced WNT/beta-catenin signaling by high glucose. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 52, R51–R66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, T.Y.; Park, J.; Scherer, P.E. Hyperglycemia as a risk factor for cancer progression. Diabetes Metab. J. 2014, 38, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, S.F.A. The TCF7L2 Locus: A Genetic Window Into the Pathogenesis of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.D.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wei, Y.J.; Jia, X.B.; Yin, W.; Shu, L. Geniposide promotes beta-cell regeneration and survival through regulating beta-catenin/TCF7L2 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Z.; Anini, Y.; Fang, X.; Mills, G.; Brubaker, P.L.; Jin, T. Transcriptional activation of the proglucagon gene by lithium and beta-catenin in intestinal endocrine L cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, N.M.; Pritchard, L.E.; Smith, D.M.; White, A. Processing of proglucagon to GLP-1 in pancreatic alpha-cells: Is this a paracrine mechanism enabling GLP-1 to act on beta-cells? J. Endocrinol. 2011, 211, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habener, J.F.; Stanojevic, V. Alpha cells come of age. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, D.A.; D’Alessio, D.A. Physiology of proglucagon peptides: Role of glucagon and GLP-1 in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbus, J.; Chiang, Y.; Shao, W.; Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Gaisano, H.Y.; Wang, Q.; Irwin, D.M.; Jin, T. Insulin treatment and high-fat diet feeding reduces the expression of three Tcf genes in rodent pancreas. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 207, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, D.J.; Leitner, J.W.; Watson, P.; Nesterova, A.; Reusch, J.E.; Goalstone, M.L.; Draznin, B. Insulin-induced adipocyte differentiation. Activation of CREB rescues adipogenesis from the arrest caused by inhibition of prenylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 28430–28435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, T.J.J.; Nusse, R. Running Against the Wnt: How Wnt/beta-Catenin Suppresses Adipogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldes, M.; Zuo, Y.; Morrison, R.F.; Silva, D.; Park, B.H.; Liu, J.; Farmer, S.R. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma suppresses Wnt/beta-catenin signalling during adipogenesis. Biochem. J. 2003, 376, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ayala, I.; Shannon, C.; Fourcaudot, M.; Acharya, N.K.; Jenkinson, C.P.; Heikkinen, S.; Norton, L. The Diabetes Gene and Wnt Pathway Effector TCF7L2 Regulates Adipocyte Development and Function. Diabetes 2018, 67, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, T.; Asaba, H.; Kang, M.J.; Ikeda, Y.; Sone, H.; Takada, S.; Kim, D.H.; Ioka, R.X.; Ono, M.; Tomoyori, H.; et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) is essential for normal cholesterol metabolism and glucose-induced insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.F.; Xiong, D.H.; Shen, H.; Zhao, L.J.; Xiao, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, T.L.; Recker, R.R.; Deng, H.W. Polymorphisms of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene are associated with obesity phenotypes in a large family-based association study. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 43, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, N.Y.; Neville, M.J.; Marinou, K.; Hardcastle, S.A.; Fielding, B.A.; Duncan, E.L.; McCarthy, M.I.; Tobias, J.H.; Gregson, C.L.; Karpe, F.; et al. LRP5 regulates human body fat distribution by modulating adipose progenitor biology in a dose- and depot-specific fashion. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foer, D.; Zhu, M.; Cardone, R.L.; Simpson, C.; Sullivan, R.; Nemiroff, S.; Lee, G.; Kibbey, R.G.; Petersen, K.F.; Insogna, K.L. Impact of gain-of-function mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) on glucose and lipid homeostasis. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, C.; Lagathu, C.; Sethi, J.K.; Vidal-Puig, A. Adipogenesis and WNT signalling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.L.; Vidal-Puig, A.J. Adipose tissue expandability in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, S7–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, N.A.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B. Lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue and lipotoxicity. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braissant, O.; Foufelle, F.; Scotto, C.; Dauca, M.; Wahli, W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): Tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology 1996, 137, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansen, A.; Guardiola-Diaz, H.; Rafter, J.; Branting, C.; Gustafsson, J.A. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) in the mouse colonic mucosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 222, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, S.; Auwerx, J.; Argmann, C.A. PPARgamma in human and mouse physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1771, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettor, R.; Milan, G.; Franzin, C.; Sanna, M.; De Coppi, P.; Rizzuto, R.; Federspil, G. The origin of intermuscular adipose tissue and its pathophysiological implications. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 297, E987–E998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammone, G.; Karaz, S.; Lukjanenko, L.; Winkler, C.; Sizzano, F.; Jacot, G.; Migliavacca, E.; Palini, A.; Desvergne, B.; Gilardi, F.; et al. PPARgamma Controls Ectopic Adipogenesis and Cross-Talks with Myogenesis During Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggio, A.; Spada, F.; Rosina, M.; Massacci, G.; Zuccotti, A.; Fuoco, C.; Gargioli, C.; Castagnoli, L.; Cesareni, G. The immunosuppressant drug azathioprine restrains adipogenesis of muscle Fibro/Adipogenic Progenitors from dystrophic mice by affecting AKT signaling. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Shan, T.; Wang, Y. Betaine promotes lipid accumulation in adipogenic-differentiated skeletal muscle cells through ERK/PPARgamma signalling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 447, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talchai, C.; Xuan, S.; Lin, H.V.; Sussel, L.; Accili, D. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic beta cell failure. Cell 2012, 150, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, G.A.; Pullen, T.J.; Hodson, D.J.; Martinez-Sanchez, A. Pancreatic beta-cell identity, glucose sensing and the control of insulin secretion. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; York, N.W.; Nichols, C.G.; Remedi, M.S. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation in diabetes and redifferentiation following insulin therapy. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinti, F.; Bouchi, R.; Kim-Muller, J.Y.; Ohmura, Y.; Sandoval, P.R.; Masini, M.; Marselli, L.; Suleiman, M.; Ratner, L.E.; Marchetti, P.; et al. Evidence of beta-Cell Dedifferentiation in Human Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ustinov, J.; Pulkkinen, M.A.; Lundin, K.; Korsgren, O.; Otonkoski, T. Characterization of endocrine progenitor cells and critical factors for their differentiation in human adult pancreatic cell culture. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2007–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.P.; Kopp, J.L.; Sandhu, M.; Dubois, C.L.; Seymour, P.A.; Grapin-Botton, A.; Sander, M. A Notch-dependent molecular circuitry initiates pancreatic endocrine and ductal cell differentiation. Development 2012, 139, 2488–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.J.; Sussel, L. Nkx2.2 regulates beta-cell function in the mature islet. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1999–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.J.; Loomis, Z.L.; Sussel, L. Nkx2.2-repressor activity is sufficient to specify alpha-cells and a small number of beta-cells in the pancreatic islet. Development 2007, 134, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, L.A.; Gu, D.; Sarvetnick, N.; Edlund, H.; Phillips, J.M.; Fulford, T.; Cooke, A. alpha-Cell neogenesis in an animal model of IDDM. Diabetes 1997, 46, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.H.; Ko, S.H.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, J.M.; Ahn, Y.B.; Song, K.H.; Yoo, S.J.; Kang, M.I.; Cha, B.Y.; Lee, K.W.; et al. Selective beta-cell loss and alpha-cell expansion in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Korea. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2300–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Sun, L.; Chen, B.; Han, Y.; Pang, J.; Wu, W.; Qi, R.; Zhang, T.M. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for RT-qPCR studies in three metabolism related tissues of mice after caloric restriction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshima, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Kawashimo, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Ohkohchi, N.; Taniguchi, H. Isolation of mouse pancreatic ductal progenitor cells expressing CD133 and c-Met by flow cytometric cell sorting. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.L.; Liu, F.F.; Sander, M. Nkx6.1 is essential for maintaining the functional state of pancreatic beta cells. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martovetsky, G.; Tee, J.B.; Nigam, S.K. Hepatocyte nuclear factors 4alpha and 1alpha regulate kidney developmental expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badders, N.M.; Goel, S.; Clark, R.J.; Klos, K.S.; Kim, S.; Bafico, A.; Lindvall, C.; Williams, B.O.; Alexander, C.M. The Wnt receptor, Lrp5, is expressed by mouse mammary stem cells and is required to maintain the basal lineage. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, T.A.; Kaneto, H.; Miyatsuka, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kato, K.; Shimomura, I.; Stein, R.; Matsuhisa, M. Regulation of MafA expression in pancreatic beta-cells in db/db mice with diabetes. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Kudo, T.; Ogata, K.; Hamada, M.; Nakamura, M.; Kito, K.; Abe, Y.; Ueda, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Engel, J.D.; et al. Neither MafA/L-Maf nor MafB is essential for lens development in mice. Genes Cells 2009, 14, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, T.; Hamada, M.; Morito, N.; Terunuma, T.; Hasegawa, K.; Zhang, C.; Yokomizo, T.; Esaki, R.; Kuroda, E.; Yoh, K.; et al. MafB is essential for renal development and F4/80 expression in macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 5715–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bribian, A.; Fontana, X.; Llorens, F.; Gavin, R.; Reina, M.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Torres, J.M.; de Castro, F.; del Rio, J.A. Role of the cellular prion protein in oligodendrocyte precursor cell proliferation and differentiation in the developing and adult mouse CNS. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisle, J.C.; Martignat, L.; Bach, J.M.; Bosch, S.; Louzier, V. Bipotential mouse embryonic liver (BMEL) cells spontaneously express Pdx1 and Ngn3 but do not undergo further pancreatic differentiation upon Hes1 down-regulation. BMC Res. Notes 2008, 1, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawki, H.H.; Oishi, H.; Usui, T.; Kitadate, Y.; Basha, W.A.; Abdellatif, A.M.; Hasegawa, K.; Okada, R.; Mochida, K.; El-Shemy, H.A.; et al. MAFB is dispensable for the fetal testis morphogenesis and the maintenance of spermatogenesis in adult mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.; Shao, W.; Chiang, Y.T.; Jin, T. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 is upregulated by insulin and represses hepatic gluconeogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E1166–E1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alquier, T.; Poitout, V. Considerations and guidelines for mouse metabolic phenotyping in diabetes research. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, C.C.; Wasserman, D.H.; Lee-Young, R.S.; Lantier, L. Approach to assessing determinants of glucose homeostasis in the conscious mouse. Mamm. Genome 2014, 25, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burant, C.F.; Flink, S.; DePaoli, A.M.; Chen, J.; Lee, W.S.; Hediger, M.A.; Buse, J.B.; Chang, E.B. Small intestine hexose transport in experimental diabetes. Increased transporter mRNA and protein expression in enterocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, V.; Le Gall, M.; Fioramonti, X.; Stolarczyk, E.; Blazquez, A.G.; Klein, C.; Prigent, M.; Serradas, P.; Cuif, M.H.; Magnan, C.; et al. Insulin internalizes GLUT2 in the enterocytes of healthy but not insulin-resistant mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, G.L.; Brot-Laroche, E. Apical GLUT2: A major pathway of intestinal sugar absorption. Diabetes 2005, 54, 3056–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Kerschner, J.L.; Harris, A. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 coordinates multiple processes in a model of intestinal epithelial cell function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1859, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Vardarli, I.; Deacon, C.F.; Holst, J.J.; Meier, J.J. Secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in type 2 diabetes: What is up, what is down? Diabetologia 2011, 54, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.J.; Nauck, M.A. Is the diminished incretin effect in type 2 diabetes just an epi-phenomenon of impaired beta-cell function? Diabetes 2010, 59, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, J.J.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsboll, T.; Krarup, T.; Madsbad, S. Loss of incretin effect is a specific, important, and early characteristic of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, S251–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahren, B. Incretin dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: Clinical impact and future perspectives. Diabetes Metab. 2013, 39, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Sun, J.; Lim, G.E.; Fantus, I.G.; Brubaker, P.L.; Jin, T. Cross talk between the insulin and Wnt signaling pathways: Evidence from intestinal endocrine L cells. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.T.; Ip, W.; Jin, T. The role of the Wnt signaling pathway in incretin hormone production and function. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszka, K.; Picard, A.; Ellero-Simatos, S.; Chen, J.; Defernez, M.; Paramalingam, E.; Pigram, A.; Vanoaica, L.; Canlet, C.; Parini, P.; et al. Intestinal PPARgamma signalling is required for sympathetic nervous system activation in response to caloric restriction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.H.; Huang, J.; Duvel, K.; Boback, B.; Wu, S.; Squillace, R.M.; Wu, C.L.; Manning, B.D. Insulin stimulates adipogenesis through the Akt-TSC2-mTORC1 pathway. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, G.; Simcox, J.; Seldin, M.M.; Parnell, T.J.; Stubben, C.; Just, S.; Begaye, L.; Lusis, A.J.; Villanueva, C.J. Targeted deletion of Tcf7l2 in adipocytes promotes adipocyte hypertrophy and impaired glucose metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2019, 24, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, J.K.; Vidal-Puig, A.J. Thematic review series: Adipocyte biology. Adipose tissue function and plasticity orchestrate nutritional adaptation. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Hegde, V.; Dubuisson, O.; Gao, Z.; Dhurandhar, N.V.; Ye, J. Interplay of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines to determine lipid accretion in adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Berger, J.; Hu, E.; Szalkowski, D.; White-Carrington, S.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Moller, D.E. Negative regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma gene expression contributes to the antiadipogenic effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Mol. Endocrinol. 1996, 10, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, W.P.; Sethi, J.K. TNF-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastard, J.P.; Hainque, B.; Dusserre, E.; Bruckert, E.; Robin, D.; Vallier, P.; Perche, S.; Robin, P.; Turpin, G.; Jardel, C.; et al. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma, leptin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA expression during very low calorie diet in subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese women. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 1999, 15, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festuccia, W.T.; Blanchard, P.G.; Deshaies, Y. Control of Brown Adipose Tissue Glucose and Lipid Metabolism by PPARgamma. Front. Endocrinol. 2011, 2, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.J.; Park, J.; Kim, S.S.; Oh, H.; Choi, C.S.; Koo, S.H. TCF7L2 modulates glucose homeostasis by regulating CREB- and FoxO1-dependent transcriptional pathway in the liver. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Ohtake, T.; Motomura, W.; Takahashi, N.; Hosoki, Y.; Miyoshi, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Saito, H.; Kohgo, Y.; Okumura, T. Increased expression of PPARgamma in high fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 336, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Xu, J.; Wei, G.; Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Wang, G.; Li, F.; Jiang, F. HNF1alpha Controls Liver Lipid Metabolism and Insulin Resistance via Negatively Regulating the SOCS-3-STAT3 Signaling Pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 5483946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Deng, X.; Huang, Z.W.; Wei, J.; Ding, C.H.; Feng, R.X.; Zeng, X.; Chen, Y.X.; Ding, J.; Qiu, L.; et al. An HNF1alpha-regulated feedback circuit modulates hepatic fibrogenesis via the crosstalk between hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Ding, K.; Wang, K.Q.; He, J.; Yin, C.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, W.F.; Shi, Y.Q. Deletion of HNF1alpha in hepatocytes results in fatty liver-related hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, T.H.; Song, X.L.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.I.; Ahn, Y.H. Identification and characterization of peroxisome proliferator response element in the mouse GLUT2 promoter. Exp. Mol. Med. 2005, 37, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postic, C.; Burcelin, R.; Rencurel, F.; Pegorier, J.P.; Loizeau, M.; Girard, J.; Leturque, A. Evidence for a transient inhibitory effect of insulin on GLUT2 expression in the liver: Studies in vivo and in vitro. Biochem. J. 1993, 293, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patitucci, C.; Couchy, G.; Bagattin, A.; Caneque, T.; de Reynies, A.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Rodriguez, R.; Pontoglio, M.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Pende, M.; et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha suppresses steatosis-associated liver cancer by inhibiting PPARgamma transcription. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1873–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, F.; Le Grand, F. Wnt Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Development and Regeneration. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2018, 153, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, K.; Naito, A.T.; Higo, T.; Nakagawa, A.; Shibamoto, M.; Sakai, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Kuramoto, Y.; Sumida, T.; Nomura, S.; et al. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Contributes to Skeletal Myopathy in Heart Failure via Direct Interaction with Forkhead Box O. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K.; Kuang, S.; Taketo, M.M.; Rudnicki, M.A. Canonical Wnt signaling induces BMP-4 to specify slow myofibrogenesis of fetal myoblasts. Skelet. Muscle 2013, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertino, A.M.; Taylor-Jones, J.M.; Longo, K.A.; Bearden, E.D.; Lane, T.F.; McGehee, R.E., Jr.; MacDougald, O.A.; Peterson, C.A. Wnt10b deficiency promotes coexpression of myogenic and adipogenic programs in myoblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; De Aguiar, R.B.; Naik, S.; Mani, S.; Ostadsharif, K.; Wencker, D.; Sotoudeh, M.; Malekzadeh, R.; Sherwin, R.S.; Mani, A. LRP6 enhances glucose metabolism by promoting TCF7L2-dependent insulin receptor expression and IGF receptor stabilization in humans. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewska-Kupczewska, M.; Stefanowicz, M.; Matulewicz, N.; Nikolajuk, A.; Straczkowski, M. Wnt Signaling Genes in Adipose Tissue and Skeletal Muscle of Humans with Different Degrees of Insulin Sensitivity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3079–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Abrams-Carter, L.; Mudaliar, S.; Nikoulina, S.E.; Henry, R.R. PPAR-gamma gene expression is elevated in skeletal muscle of obese and type II diabetic subjects. Diabetes 1997, 46, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszynska, Y.T.; Mukherjee, R.; Jow, L.; Dana, S.; Paterniti, J.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-gamma expression in obesity and non- insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, R.H.; Mathews, S.T.; Camp, H.S.; Ding, L.; Leff, T. Selective activation of PPARgamma in skeletal muscle induces endogenous production of adiponectin and protects mice from diet-induced insulin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 298, E28–E37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, B.S.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Carter, L.; Nikoulina, S.E.; Mudaliar, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Paterniti, J.R., Jr.; Henry, R.R. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma and retinoid X receptor (RXR) agonists have complementary effects on glucose and lipid metabolism in human skeletal muscle. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, C.; Nie, H.; Pang, Q.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Z.; Song, Y. G Allele of the rs1801282 Polymorphism in PPARgamma Gene Confers an Increased Risk of Obesity and Hypercholesterolemia, While T Allele of the rs3856806 Polymorphism Displays a Protective Role Against Dyslipidemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 919087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Xing, Y.; Lv, X.; Ma, H.; Song, G. The role of CD36-Fabp4-PPARgamma in skeletal muscle involves insulin resistance in intrauterine growth retardation mice with catch-up growth. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoio, D.M.; Koves, T.R. Skeletal muscle adaptation to fatty acid depends on coordinated actions of the PPARs and PGC1 alpha: Implications for metabolic disease. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martin, J.M.; Torres-Mata, L.B.; Cazorla-Rivero, S.; Fernandez-Santana, C.; Gomez-Bentolila, E.; Clavo, B.; Rodriguez-Esparragon, F. An Artificial Intelligence Prediction Model of Insulin Sensitivity, Insulin Resistance, and Diabetes Using Genes Obtained through Differential Expression. Genes 2023, 14, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Cui, X.; Maianu, L.; Rhees, B.; Rosinski, J.; So, W.V.; Willi, S.M.; Osier, M.V.; Hill, H.S.; et al. The effect of insulin on expression of genes and biochemical pathways in human skeletal muscle. Endocrine 2007, 31, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, W.; Iwasa, H.; Tumurkhuu, M. Role of the Transcription Factor MAFA in the Maintenance of Pancreatic beta-Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artner, I.; Blanchi, B.; Raum, J.C.; Guo, M.; Kaneko, T.; Cordes, S.; Sieweke, M.; Stein, R. MafB is required for islet beta cell maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3853–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M.C.; Jung, Y.; Ugboma, C.M.; Shimbo, M.; Kuno, A.; Basha, W.A.; Kudo, T.; Oishi, H.; Takahashi, S. MafB Is Critical for Glucagon Production and Secretion in Mouse Pancreatic alpha Cells in Vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2018, 38, e00504-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.; Katoh, M.C.; Abdellatif, A.M.; Xiafukaiti, G.; Elzeftawy, A.; Ojima, M.; Mizuno, S.; Kuno, A.; Takahashi, S. Uncovering the role of MAFB in glucagon production and secretion in pancreatic alpha-cells using a new alpha-cell-specific Mafb conditional knockout mouse model. Exp. Anim. 2020, 69, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiafukaiti, G.; Maimaiti, S.; Ogata, K.; Kuno, A.; Kudo, T.; Shawki, H.H.; Oishi, H.; Takahashi, S. MafB Is Important for Pancreatic beta-Cell Maintenance under a MafA-Deficient Condition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2019, 39, e00080-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelin Klemen, M.; Kopecky, J.; Dolensek, J.; Stozer, A. Human Beta Cell Functional Adaptation and Dysfunction in Insulin Resistance and Its Reversibility. Nephron 2024, 148, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calanna, S.; Christensen, M.; Holst, J.J.; Laferrere, B.; Gluud, L.L.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F.K. Secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analyses of clinical studies. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovsek, S.; Dolensek, J.; Daris, B.; Valladolid-Acebes, I.; Vajs, T.; Leitinger, G.; Stozer, A.; Klemen, M.S. Western diet-induced ultrastructural changes in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1380564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamoto, I.; Kubota, N.; Nakaya, K.; Kumagai, K.; Hashimoto, S.; Kubota, T.; Inoue, M.; Kajiwara, E.; Katsuyama, H.; Obata, A.; et al. TCF7L2 in mouse pancreatic beta cells plays a crucial role in glucose homeostasis by regulating beta cell mass. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Su, J.; Bailey, K.; Ottosson-Laakso, E.; Shcherbina, L.; Oskolkov, N.; Zhang, E.; Thevenin, T.; Fadista, J.; et al. TCF7L2 is a master regulator of insulin production and processing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6419–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogh, K.L.; Craig, M.N.; Uy, C.E.; Nygren, H.; Asadi, A.; Speck, M.; Fraser, J.D.; Rudecki, A.P.; Baker, R.K.; Oresic, M.; et al. Overexpression of PPARgamma specifically in pancreatic beta-cells exacerbates obesity-induced glucose intolerance, reduces beta-cell mass, and alters islet lipid metabolism in male mice. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 3843–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Haneda, M.; Tsuyama, T.; Mizumoto, T.; Yoshizawa, T.; Kitamura, T.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Yamamura, K.I.; Yamagata, K. HNF1alpha controls glucagon secretion in pancreatic alpha-cells through modulation of SGLT1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.M.; Jiang, B.G.; Sun, L.L. HNF1A: From Monogenic Diabetes to Type 2 Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 829565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrat, S. Beta-Cell Dedifferentiation in Type 2 Diabetes: Concise Review. Stem. Cells 2019, 37, 1267–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.; Zervou, S.; Mattsson, G.; Abouna, S.; Zhou, L.; Ifandi, V.; Pelengaris, S.; Khan, M. c-Myc directly induces both impaired insulin secretion and loss of beta-cell mass, independently of hyperglycemia in vivo. Islets 2010, 2, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, S.; Roy, N.; Russ, H.A.; Leonhardt, L.; French, E.K.; Roy, R.; Bengtsson, H.; Scott, D.K.; Stewart, A.F.; Hebrok, M. Replication confers beta cell immaturity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner-Weir, S.; Toschi, E.; Inada, A.; Reitz, P.; Fonseca, S.Y.; Aye, T.; Sharma, A. The pancreatic ductal epithelium serves as a potential pool of progenitor cells. Pediatr. Diabetes 2004, 5, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner-Weir, S.; Weir, G.C. New sources of pancreatic beta-cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Wu, H. Regenerating beta cells of the pancreas-potential developments in diabetes treatment. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujadas, G.; Cervantes, S.; Tutusaus, A.; Ejarque, M.; Sanchez, L.; Garcia, A.; Esteban, Y.; Fargas, L.; Alsina, B.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Wnt9a deficiency discloses a repressive role of Tcf7l2 on endocrine differentiation in the embryonic pancreas. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nutritional Ingredients | CD | WD |

|---|---|---|

| Arachidonic acid, % | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Carbohydrates, % | 60.1 | 50.0 |

| Cholesterol, % | 0.018 | 0.21 |

| Essential amino acids | 5.5 | 7.3 |

| Fat, % | 4.5 | 21.0 |

| Fiber, % | 4.9 | 0.2 |

| Linoleic acid, % | 0.19 | 1.48 |

| Minerals, % | 2.65 | 0.04 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids, % | 23.0 | 12.6 |

| Nonessential amino acids | 8.0 | 12.8 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids, % | 53.8 | 2.86 |

| Proteins, % | 14.5 | 20.0 |

| Saturated fatty acids, % | 22.0 | 25.8 |

| Vitamins, % | <5 | 0.01 |

| Water, % | <11 | <9 |

| Energy profile | ||

| Carbohydrates, % of kcal | 71.7 | 43.0 |

| Energy, kcal/g | 3.0 | 4.7 |

| Fat, % of kcal | 10.5 | 40.0 |

| Proteins, % of kcal | 40.0 | 17.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radulović, D.; Dolenšek, J.; Stožer, A.; Potočnik, U. Western Diet Induces Changes in Gene Expression in Multiple Tissues During Early Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in Male C57BL/6 Mice. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121053

Radulović D, Dolenšek J, Stožer A, Potočnik U. Western Diet Induces Changes in Gene Expression in Multiple Tissues During Early Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in Male C57BL/6 Mice. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121053

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadulović, Djordje, Jurij Dolenšek, Andraž Stožer, and Uroš Potočnik. 2025. "Western Diet Induces Changes in Gene Expression in Multiple Tissues During Early Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in Male C57BL/6 Mice" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121053

APA StyleRadulović, D., Dolenšek, J., Stožer, A., & Potočnik, U. (2025). Western Diet Induces Changes in Gene Expression in Multiple Tissues During Early Insulin Resistance and Glucose Intolerance in Male C57BL/6 Mice. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121053