4.1. The Effects of Maternal Supplementation of Clofibrate on Carnitine Concentrations in Sow Milk Throughout Lactation

There have been several previous studies evaluating milk carnitine concentration in sows; however, unlike the present study, they focused only on a single day of lactation [

31]). The total concentration of carnitine measured in our study was higher than that in milk measured on d11 by Ramanau et al. [

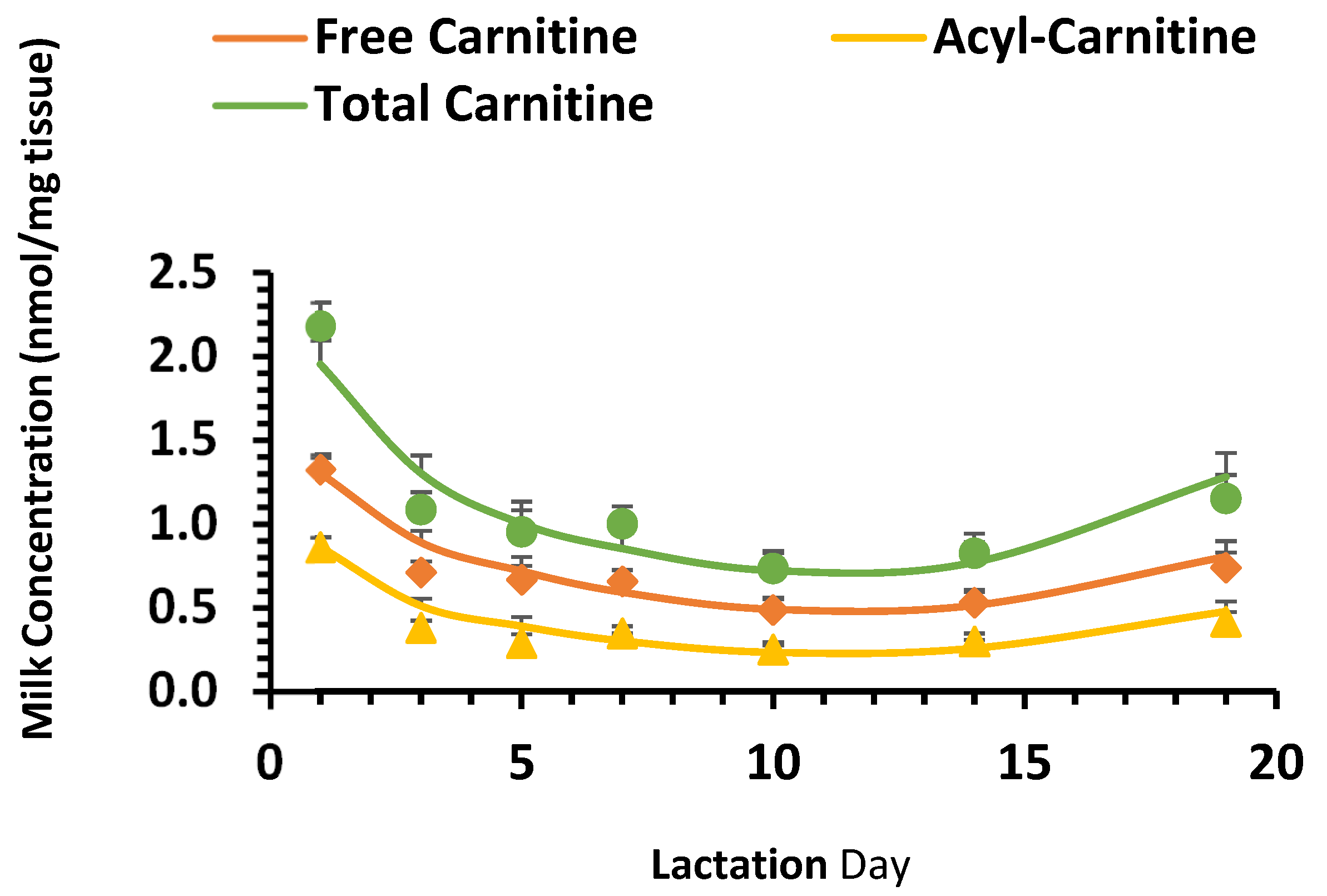

31]. Considering that the data in sow milk reported previously was from a single day mid-lactation and from sows of different breeds, the observed differences could be due to variations in dietary carnitine level, the capacity of carnitine synthesis, and metabolic (physiological) status. The reproductive productivity of sows such as litter size and milk production could also affect milk carnitine concentrations. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine milk carnitine repeatedly over the course of the entire lactation period. The data presented here greatly improves our knowledge of the dynamic changes during the lactation period (

Figure A1). The strong correlations between sow’s milk, piglet’s plasma, and intestinal mucosa, as well as the total measured (plasma+ intestinal mucosa + liver) carnitines suggest that the carnitine in sow’s milk plays an important role in carnitine intake and metabolic development in neonatal piglets.

Maternal treatment with clofibrate during the last week of gestation and the first week of lactation had no impact on milk free carnitine level but tended to increase (p = 0.089) milk acyl-carnitine and total carnitine concentrations. Very limited information about the effect of clofibrate dosage and treatment duration on milk carnitine concentrations can be found in the literature. The subdued response that we observed could be due, at least partially, to the duration of clofibrate treatment and/or the efficiency of clofibrate absorption, which is supported by the result from milk clofibrate analysis.

No clofibrate or its metabolites were detected in the milk samples collected in our study. Clofibrate transfer from mother to offspring via milk was observed in rats [

32]; however, clofibrate (500 mg kg

−1) was administered to the lactating rats via intraperitoneal injection rather than provided as a feed additive as in the present study. In addition, reports from human studies indicate that infant drug exposure via breast milk is low and the relative infant dose expressed as a percentage of the similarly adjusted mother’s dose is <10% for most drugs [

33]. This suggests that the dietary clofibrate level used in our study may have been lower than was needed to produce a substantial response in milk clofibrate concentration.

The carnitine concentrations in milk were significantly influenced by the stage of lactation. Free carnitine, acyl-carnitine, and total carnitine follow the same nonlinear pattern (

Figure A1), which is the highest at d1, then decreases after d1, with the lowest levels at d10. Similar patterns were reported in human milk; the concentration of carnitine decreased by about 50% by postpartum d40–50 [

14,

34]. The changes through lactation were not associated with diet as this remained constant during the lactation period, although feed intake per day could vary. The carnitine levels were examined previously in sow colostrum on d1 and milk on d7 [

35] and the total carnitine concentration in colostrum was 1.54-fold of that in milk on d7. Consistent with Birkenfeld’s report [

35], the total carnitine measured on d1 was 1.5-fold of that on d7 in our study. With a piglet’s limited capacity for the de novo biosynthesis of carnitine [

36], it would be expected that the levels of milk carnitine are higher at birth and decrease with lactation days due to the downregulation of PPARα in sows [

23].

A broad range of acyl-carnitine concentrations (13–47%) have been reported in milk from different species [

15]. It is generally believed that variation is related to maternal systemic and/or breast metabolic status. The mild increase in acyl-carnitine and Ac/Fc in the milk of clofibrate-treated sows appeared to be associated with maternal/mammary metabolic status, implying that a metabolic change might occur in mammary tissue after clofibrate supplementation. However, there was no detectable interaction between clofibrate and lactation days. Consistent with the acyl-carnitine concentration, the percentage of acyl-carnitine decreased while the percentage of free carnitine increased quadratically as lactation progressed. Ac/Fc followed the same pattern. These results are in agreement with the results observed in other mammals; the maternal metabolic rate is usually the highest immediately postpartum and gradually decreases as lactation progresses through mid and late stages [

37].

4.2. The Effects of Maternal Supplementation of Clofibrate and Lactation Days on Carnitine Concentrations in Plasma, Liver and Intestinal Mucosa of the Suckling Piglets

The plasma levels of carnitine and acyl-carnitine were similar as that reported by Lyvers Peffer et al. [

38] but were higher than that reported by Birkenfeld et al. [

35] and Kaup et al. [

39]. Compared to other species, the plasma carnitine concentration is similar to that of the breast-fed human infant [

40], higher than that of rabbits [

41] and rats [

42], and lower than piglets receiving milk formula composed primarily of whey [

13]. This difference illustrates both inter-species differences as well as the differences in concentrations between milk sources. No differences were detected in the plasma carnitine levels or its distribution and Ac/Fc in piglets from sows with or without the supplementation of clofibrate. However, the results showed that the percentage of free carnitine tended to decrease, with the percentage of acyl-carnitine increasing by maternal clofibrate, suggesting that clofibrate could affect the plasma carnitine component by altering the metabolic status. Additionally, the carnitine in all forms examined decreased with postnatal age. Linear and/or quadratic responses to postnatal age were detected in carnitine, acyl-carnitine, and total carnitine. These observations are consistent with the results reported previously [

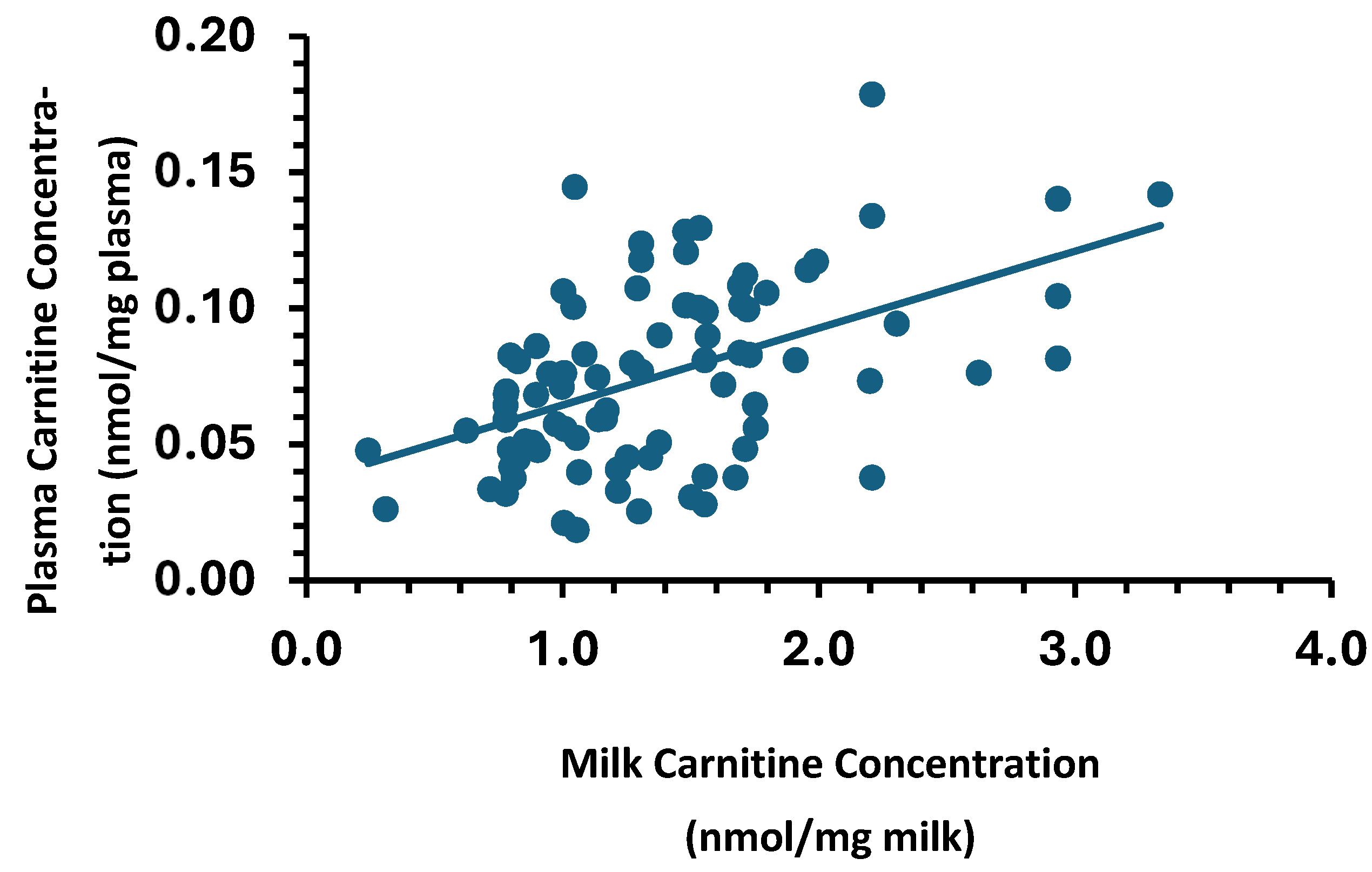

43]. The changes followed the same pattern as observed in sow milk. The correlation assay indicated that the concentrations of carnitine, acyl-carnitine, and total carnitine are closely associated with the levels in sow milk (

Figure A2), demonstrating that plasma carnitine status in neonates was affected by the status of the mother’s milk. However, the concentration of carnitine in maternal milk was much higher than that in the plasma of the piglets. Especially Ac/Fc, which was five-fold higher in sow milk than in piglets’ plasma, suggesting that absorption might differ for carnitine and carnitine esters, possibly due to differing affinities of carnitine transporters. The plasma percentage of free carnitine in total carnitines and Ac/Fc are considered to be markers of carnitine deficiency and insufficiency [

44], respectively. It was suggested that the percentage of free carnitine being less than 70% indicated carnitine deficiency and Ac/Fc being greater than 0.40 indicated carnitine insufficiency. Although there were differences in the percentage of free carnitine and Ac/Fc at different postnatal stages, all measured values for the percentage of free carnitine were higher than 70% and for Ac/Fc were lower than 0.40. These results imply that carnitine status and FA oxidation were typical of postnatal development.

Numerous studies have examined the intestinal ability to absorb carnitine and its relationship to the expression of

OCTNs within the intestines, but very few studies have examined the carnitine levels present in the intestine mucosa and their changes throughout postnatal development. A previous study with rats showed that carnitine concentration in the mucosa of the proximal small intestine was 0.31 (nmol/mg wet tissue) in a fasting state and 2.5 nmol after enteral loading with 5 mL of a 2 mM carnitine solution [

42]. A study with suckling guinea pigs showed that carnitine concentration peaked after 3 days (0.79) and ranged from 0.35 to 0.91 nmol/mg from d1 to d29 [

25]. Carnitine content of the small intestinal mucosa of rats decreases postnatally, reaching adult levels at the time of weaning [

45]. In agreement with previous findings in other mammals, the total concentration of carnitine measured in the intestinal mucosa of piglets on average was 0.86 (nmol/mg wet tissue), from our previous work [

13] and in this study. Maternal supplementation of clofibrate had no impact on carnitine content, and similar results were also observed in our previous work with one-week-old piglets receiving milk formula with and without supplementation of clofibrate [

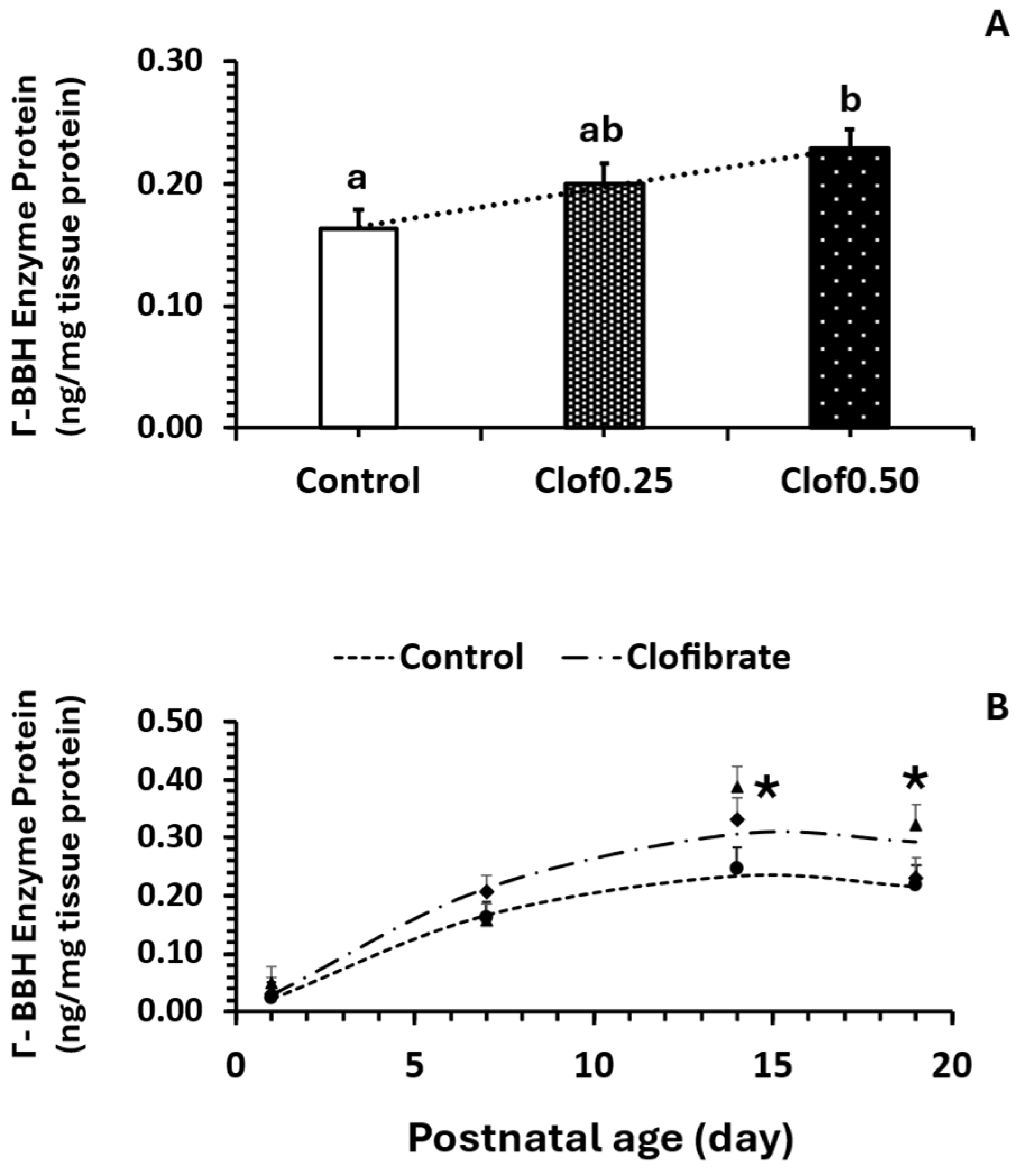

13]. Although the influences of maternal clofibrate on intestinal carnitine concentration were not detected, we noticed that the expression of

OCTN2, the primary carnitine transporter, tended to increase in pigs from sows treated with clofibrate (

p = 0.052) and was on average 93% higher than that from control sows, consistent with the result observed in rats [

20,

21]. In addition, the key enzyme protein of carnitine synthesis, BBH, increased linearly with maternal clofibrate dose. These results suggest that PPARα, indeed, played a regulatory role in intestinal uptake and synthesis of carnitine. Similarly to rodents [

46], piglets might be capable of synthesizing carnitine in the intestinal mucosa during the suckling period. In support of this, we examined the mucosa expression of genes associated with carnitine synthesis such as

ALDH9A1,

BBH, and

TMLH during the suckling period. We found that

ALDH9A1 and

TMLH had no change and maintained a low level compared to newborns, while the expression of

BBH remained at a high level throughout the lactation period and was influenced by maternal clofibrate (

p = 0.09). These findings imply that carnitine may not be synthesized from lysine, but we speculate it may be obtained by hydrolyzing 4-trimethlammoniobutanoic acid in the intestinal mucosa. Nonetheless, it is most likely that endogenously synthesized carnitine is very limited in the intestinal mucosa during the suckling period compared to the liver and kidney [

47], stressing the importance of milk as the primary source of carnitine.

Carnitine concentration increased significantly after one week, although the impact of clofibrate on concentration was limited. The increase is likely not related to an increase in transporters as we did not detect significant changes in

OCTN2 gene expression with respect to age. It has been shown in 4-week-old piglets that the level of carnitine absorption at the proximal end of the intestines can reach as high as 95% [

48], and even with high levels of carnitine supplementation, the absorption rate was still around 90%, suggesting that OCTN2 might not be a limiting factor for carnitine absorption. Moreover, a correlation between milk and intestine but not between intestine and plasma carnitine concentration was detected, emphasizing the role of the small intestine in carnitine absorption. However, BBH protein increased with the postnatal age. This link between the carnitine levels in the intestine might need to be investigated further as 4-trimethylammoniobutanoic acid can be produced by intestinal microbes [

49].

The total carnitine concentration, in general, was similar to previous work from our laboratory [

38], and others [

19,

50] for neonatal pigs. Concentrations were also similar to reports for rats [

51] and dogs [

8]. However, the acyl-carnitine concentrations varied over a wide range among these studies, demonstrating that the carnitine status in liver is sensitive to alterations to hepatic metabolism. The proportion of acyl-carnitine measured was over 50% and was higher on d1 than other days. This is consistent with increased FA oxidation, in which acetyl-carnitine is the main component of the acid-soluble products [

11]. The liver is the predominant site of carnitine biosynthesis in the sow with the kidney providing a relatively small amount, while the contribution of other tissues is negligible [

50]. Evidence from early studies showed that carnitine synthesis in the liver and kidney and uptake in the hepatocyte could be increased by the activation of PPARα [

19,

52]. Indeed, long-term clofibrate administration markedly increased the concentration of carnitine as well as the activity of mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyl-transferase in the liver [

53]. Consistent with these early findings, we also observed that liver carnitines increased greatly in newborn pigs when fed with clofibrate directly [

13]. However, here, only a small increase in free carnitine induced by maternal clofibrate supplementation was observed. Regarding the status of carnitines in milk, we postulate that the lack of response was related to the maternal clofibrate dosage, the lapsed time between supplementation and sample collection, and low efficiency of clofibrate transfer via milk. This was consistent with the tendency for an increase to

TMLH at the higher dose of maternal clofibrate.

The pattern of carnitine changes during the postnatal period looks similar to that in piglets reported by Li et al. [

54]. The concentrations increased with postnatal age from d1 to d7, and no further increase was observed after d7, though the increase in acyl-carnitine differed from the level of free carnitine. Significant quadratic responses were detected. The increase in hepatic carnitines seems not to be associated with milk concentrations but is possibly due to increased carnitine synthetic capacity and ingestion, because the milk concentration decreased at the same stage while the measured genes associated with carnitine synthesis such as

TMLH,

ALD, and

BBH as well as the transporter OCTN2 increased [

11]. This suggests that endogenously synthesized carnitine could play an important role in the liver where carnitine synthesis and metabolism exhibit robust activity with an increase in capacity as they age [

55,

56]. This likely accounts for the trends seen in the liver of these piglets. As the sow’s supply of carnitine reduced in the milk, the biosynthesis capacity of the piglets increased to compensate for the difference. The sow was still supplying ample carnitine and the piglet’s own capacity to synthesize carnitine was beginning to develop.