Assessing and Monitoring of Building Performance by Diverse Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context

- Elemental method—specific U-values were given for different construction elements;

- Target U-value method—average U-values were calculated using the total floor area, the total area of exposed elements, the proportion of windows and heating efficiency;

- Energy Rating method—ventilation rate, fabric losses, water heating requirements, internal heat and solar gains were simultaneously taken into account using the Government Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP).

- The SAP 2005 for dwellings smaller than 450 m2;

- The Simplified Building Energy model for dwellings greater than the above.

- The primary energy rate and the target primary energy rate, alongside TER and TFEE. These represent the primary energy used (kWhPE/m2/year) by the dwelling;

- The near-zero-energy requirements for new buildings state that “where a building is erected, it must be a nearly zero-energy building” [6].

1.2. Envelope

1.3. Airtightness

1.4. Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) and Ventilation

- Lack of adequate skills in installation;

- Control and operation uncertainties due to occupants’ behavior;

- No implementation of occupants’ preferences and needs at the early stage when energy-saving measures are to be placed.

2. Energy Consumption and Carbon Emissions

- Monitoring, controlling, and communicating building energy consumption;

- Planning energy consumption according to users’ patterns and needs, looking as well at the energy cost;

- Managing the energy demand via home appliances, energy storage and renewable systems.

3. Building Energy Modeling

- The traditional approach—white box;

- The data-driven approach—black box;

- The hybrid approach—grey box.

4. Surveys and Interviews

- Might take longer, with BUS survey for non-domestic buildings generally undertaken in one day;

- Appear more resistant to setting benchmarks to compare the survey’s results, due to the scale of the survey for domestic buildings;

- Might be inaccurate due to reluctant responses.

5. Assessment Schemes

5.1. Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP)

- 55% reduction in carbon emissions produced by electricity;

- Overheating risk increase, with more deep consideration of natural ventilation, which could also be impacted by noise;

- Building performance calculation could be affected negatively if thermal bridging details are not provided.

5.2. Energy Performance Certificate (EPC)

- The asset rating for the building;

- A reference value (A to G);

- Recommendation report;

- Relevant reference number;

- Address of the building;

- The date on which it was issued.

- Higher validity of the software used for the EPC;

- Improvement with deep renovation and recommendations of online tools that could compare the different options;

- An on-site inspection is mandatory.

5.3. Building Performance Evaluation (BPE)

- Review of project delivery—at this stage the team and the client experience should be evaluated;

- Project outcomes, which include interpretation and analysis of the brief;

- Building use/occupant behavior, which looks at the building fabric and its connection with the building use, and the occupant patterns;

- Occupant feedback;

- Energy use;

- System, including health and safety strategy, ventilation strategy, lighting, water and HVAC systems, control, and maintenance;

- Environmental performance, a measure of the thermal and acoustic performances, indoor air quality, heat loss, airtightness, and light levels;

- Comparisons, predicted performance versus the actual one, and use of previous studies;

- Report, to share with the client and the design team for future references.

- Design and construction audit, with analysis of quantitative data, such as SAP calculation, and qualitative data, such as photographic surveys and team interviews;

- Building envelope tests, regarding its thermal properties.

- Analysis of the commissioning and handover process;

- Building energy evaluation;

- Building environmental conditions, such as internal temperature, relative humidity, and indoor air quality;

- Analysis of occupant satisfaction, with qualitative data based on interviews, activity logging, and thermal comfort diaries.

- Aspiration, driven by investors and developers, with targets set since the beginning;

- Control, with collaboration in the supply chain for the contracting and delivery processes;

- Design for performance;

- Feedback, to address better delivery and handover;

- Knowledge improvement for all the parties involved.

5.4. Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE)

- Identify the strategy and needs;

- Identify the issues to address;

- Form a statement or brief for the POE;

- POE planning;

- POE execution;

- Report;

- Actions in response to the POE.

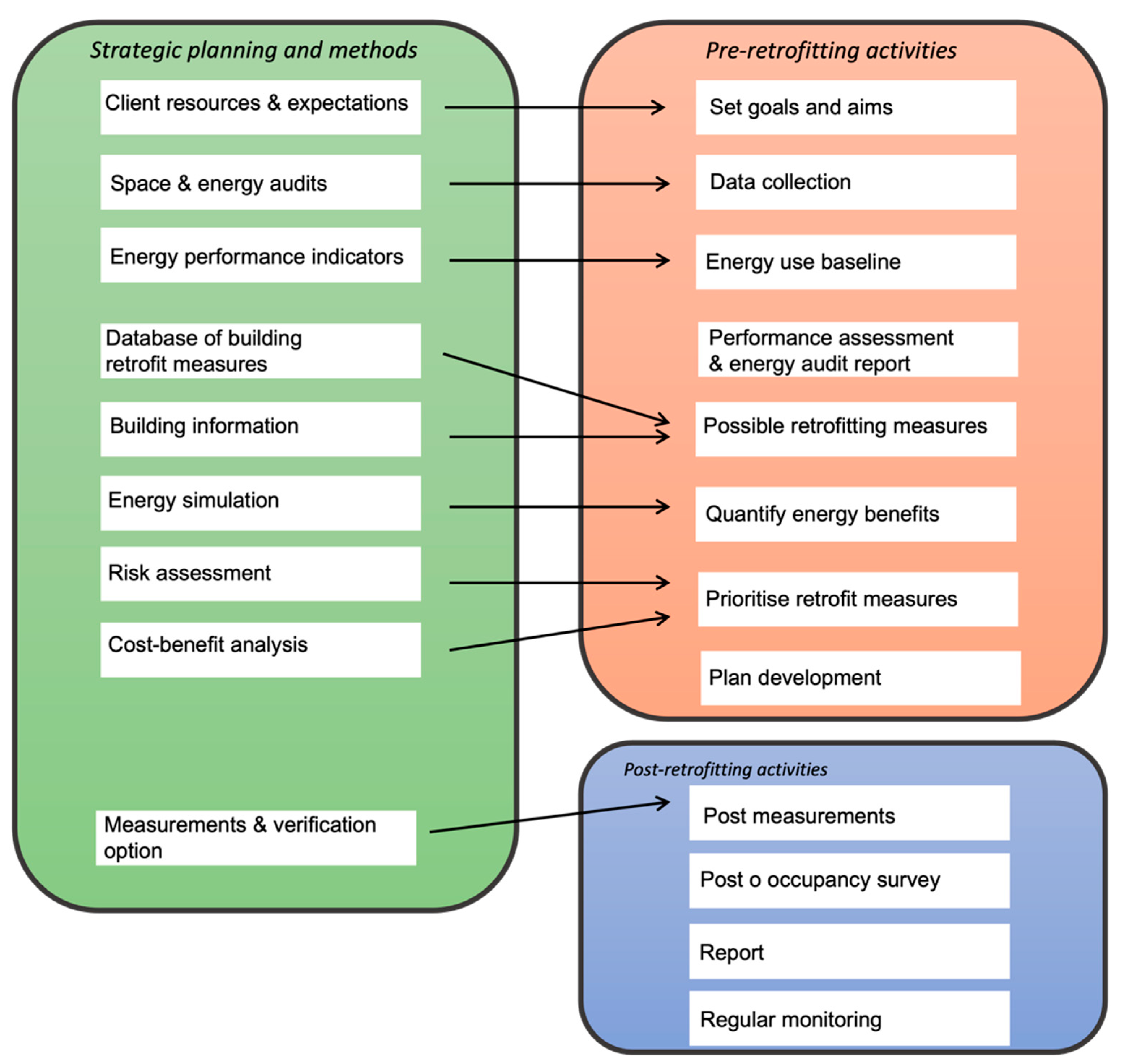

5.5. Energy Retrofit Measures (ERMs)

- Energy modeling and assessment, through surveys, simulations and interviews, to establish the building’s energy demand and the building’s physical characteristics;

- Energy retrofit design, with several options taken into considerations;

- Decision-making criteria assessment, including the economic, environmental and social aspects, and their weight for the decision-making;

- Optimal allocation of resources, evaluating the whole approach, and its objectives and constraints;

- Risk valuation.

- Consumer protection, with certified bodies that guarantee the professionality and validity of the measures adopted. Training might be necessary;

- Development of guidelines, and advice for consumers and the construction industry;

- Introduction of quality and standards, which could lead to compliance and enforcement.

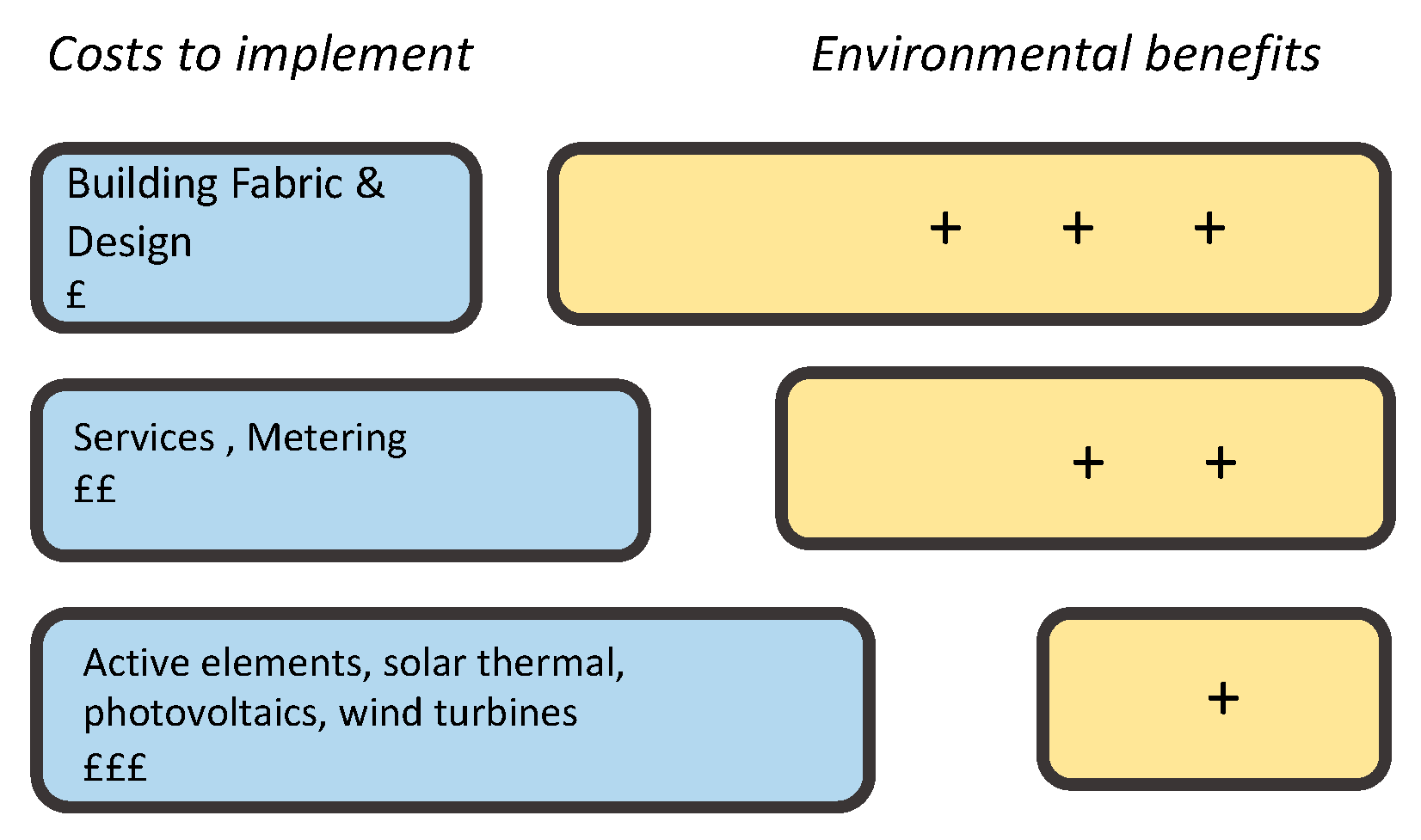

- Insulation and fabric, using a holistic approach in which environment, heritage, occupancy, and the householders’ improvement objectives drive the chosen retrofit measures;

- Smart meters, with their installation operated by skilled staff that could advise and inform the consumers;

- Home energy technologies, with the use of existing and new technologies supported by advice documents for the benefit of the supply chain and consumers.

5.6. Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM)

- Design stage (DS)—leading to an Interim BREEAM Certificate;

- Post-construction stage (PCS)—leading to a Final BREEAM Certificate;

- New benchmarks and assessment methodologies for determining energy efficiency and operational GHG emissions. Reductions in energy demand, energy consumption, and GHG emissions are key requirements in the 2011 versions;

- Updated benchmarks for construction waste and water consumption;

- Introduction of new standards for sustainable procurement and post-construction operational aftercare;

- New and updated reporting requirements of key performance indicators.

- BREEAM Communities, for the master-planning of a larger community of buildings;

- BREEAM New Construction: Buildings, for new-build, domestic and non-domestic buildings;

- BREEAM New Construction: Infrastructure, for new-build infrastructure projects;

- BREEAM In-Use, for existing non-domestic buildings in use;

- BREEAM Refurbishment and Fit Out, for domestic and non-domestic building fit-outs and refurbishments.

- The BREEAM rating level benchmarks;

- The minimum BREEAM standards;

- The environmental section weightings;

- The BREEAM assessment issues and credits.

- Outstanding: Less than the top 1% of UK new non-domestic buildings (innovator);

- Excellent: Top 10% of UK new non-domestic buildings (best practice);

- Very Good: Top 25% of UK new non-domestic buildings (advanced good practice);

- Good: Top 50% of UK new non-domestic buildings (intermediate good practice);

- Pass: Top 75% of UK new non-domestic buildings (standard good practice).

5.7. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)

- Building Design Construction, for new constructions and major renovations, core and shell development, schools, retail, data centers, warehouses and distribution centers, hospitality, and healthcare;

- Interior Design and Construction, for commercial interiors, retail, and hospitality buildings;

- Operations and Maintenance, for existing buildings and existing interiors;

- Residential, for single-family homes, multifamily homes and multifamily homes core and shell;

- Cities and Communities, regarding planning and design, or applied to existing cities and communities.

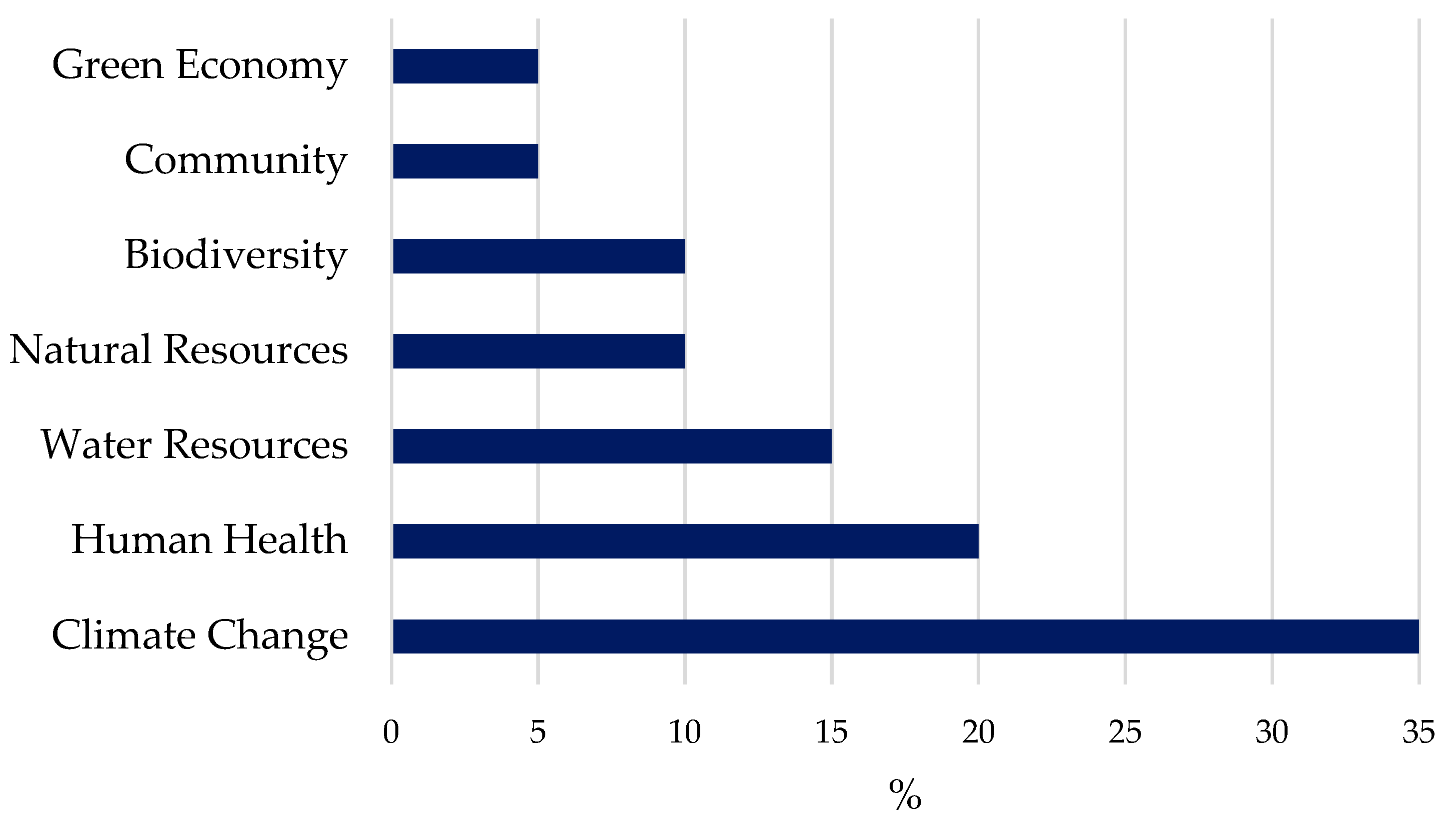

- Having less impact on global climate change;

- Adding value for human health and well-being;

- Protecting biodiversity and water resources;

- Promoting the use of sustainable materials;

- Enhancing a sustainable approach, which looks at green economy, social equity, environmental justice, and community quality of life.

- Owner’s Project Requirements Document, where the missions and goals of the projects are determined, addressing social, economic and environmental values;

- Preliminary Rating Goals, specifying the targeted certification that the project wants to obtain;

- Having an Integrated Project Team and a design charrette (at least four hours).

- LEED Pre-Assessment;

- Pre-Certification (optional);

- Design Review by GBCI after the design documentation’s submittal;

- Construction Review by the GBCI after the construction documentation’s submittal;

- Certification Awarded.

- +40 credits—Certified;

- +50 credits—Silver;

- +60 credits—Gold;

- +80 credits—Platinum.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Building Regulations 2010-Part, L. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1045920/ADL1.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- The Building Regulations 2002-Part L1A. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20141202124314/https://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/br/BR_PDF_ADL1_2002.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- The Building Regulations 2006-Part L1A. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20141202124243/https://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/br/BR_PDF_ADL1A_2006.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- The Building Regulations 2010-Part L1A. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20141202124319/https://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/br/BR_PDF_AD_L1A_2010.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- The Building Regulations 2013-Part L1A. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20150601171016/http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/br/BR_PDF_AD_L1A_2013.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- The Building Regulations 2021 edition. Available online: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/inforce/current/sl-2021-0126 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Scottish Government. Building Standards Technical Handbook 2020: Domestic. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/publications/building-standards-technical-handbook-2020-domestic/6-energy/6-2-building-insulation-envelope/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Wales Government. Building Regulations Guidance: Part L (Conservation of Fuel and Power). Available online: https://gov.wales/building-regulations (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- EN ISO 8990; Thermal insulation —Determination of Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties. Calibrated and Guarded Hot Box. BSI Standards: London, UK, 1996.

- Kelly, S.; Crawford-Brown, D.; Pollitt, M.G. Building performance evaluation and certification in the UK: Is SAP fit for purpose? Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2012, 16, 6861–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9869-1; Thermal Insulation—Building Elements—In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Part 1: Heat Flow Meter Method. ISO: Vernier, Geneva, 2014.

- Asdrubali, F.; D’Alessandro, F.; Baldinelli, G.; Bianchi, F. Evaluating in situ thermal transmittance of green buildings masonries—A case study. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2014, 1, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmina, L. BRE Guide to In-Situ U-Value Measurement of Walls in Existing Dwellings. In-Situ Measurement of U-Value. BRE. 2016. Available online: https://www.bre.co.uk/filelibrary/In-situ-measurement-of-thermal-resistance-and-thermal-transmittance-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Baker, P. Technical Paper 10. U-values and Traditional Buildings. In Situ Measurements and Their Comparisons to Calculated Values; Glasgow Caledonian University: Glasgow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, U. Clarifying the new interpretations of the concept of sustainable building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2013, 8, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.H.; Chan, W.R. Building air tightness: Research and practice. In Building Ventilation. The State of the Art, 1st ed.; Santamouris, M., Wouters, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Saving Trust. In Enhanced Construction Details: Thermal Bridging and Airtightness; Energy Saving Trust: London, UK, 2009.

- Pan, W. Relationships between air-tightness and its influencing factors of post-2006 new-build dwellings in the UK. Build Environ. 2010, 45, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamees, T. Air tightness and air leakages of new lightweight single-family detached houses in Estonia. Build Environ. 2007, 42, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Miles-Shenton, D. Airtightness of UK dwellings. In Proceedings of the Construction and Building Research Conference, London, UK; 2009; pp. 271–280. Available online: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/644/1/cobra04-3.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Salehi, A.; Torres, I.; Ramos, A. Experimental analysis of building airtightness in traditional residential Portuguese buildings. Energy Build 2017, 151, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN ISO 9972; Thermal Performance of Buildings—Determination of Air Permeability of Buildings—Fan Pressurization Method. ISO: Vernier, Geneva, 2015.

- Zheng, X.; Mazzon, J.; Wallis, I.; Wood, C.J. Airtightness measurement of an outdoor chamber using the pulse and blower door methods under various wind and leakage scenarios. Build Environ. 2020, 179, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air Tightness Testing & Measurement Association (ATTMA). Air Tightness Testing & Measurement Association Technical Standard L1. Measuring Air Permeability of Building Envelopes (Dwellings); ATTMA: Wycombe, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Šenitková, I.J. Indoor air quality—buildings design. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 93, 03001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shrestha, P.M.; Humphrey, J.L.; Barton, K.E.; Carlton, E.J.; Adgate, J.L.; Root, E.D.; Miller, S.L. Impact of low-income home energy-efficiency retrofits on building air tightness and healthy home indicators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Oreszczyn, T. The unintended consequences of decarbonising the built environment: A UK case study. Energy Build 2012, 46, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Thornton, C.R.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J. Higher energy efficient homes are associated with increased risk of doctor diagnosed asthma in a UK subpopulation. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SeppȨnen, O. Ventilation strategies for good indoor air quality and energy efficiency. Int. J. Vent. 2008, 6, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, M.; Itard, L.; Bluyssen, P.M. Indoor environmental quality related risk factors with energy-efficient retrofitting of housing: A literature review. Energy Build 2020, 221, 110102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Data & Statistics. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics?country=WORLD&fuel=Energy%20supply&indicator=TPESbySource (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- IEA. Energy Efficiency Indicators—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-indicators (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- United Nations Environment Programme. 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction. Towards a Zero-Emissions, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector. 2020. Available online: https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2020%20Buildings%20GSR_FULL%20REPORT.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- EU. Parliament Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and the Council on the Energy Performance of Buildings; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UK Green Building Council. Net Zero Carbon Buildings: A Framework Definition; UK Green Building Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; De Masi, R.F.; Dousi, M.; Hionidis, S.; Kaliakos, S.; Mastrapostoli, E.; Nomikos, M.; Santamouris, M.; Synnefa, A.; et al. Design and performance analysis of a zero-energy settlement in Greece. Int. J. Low Carbon Technol. 2017, 12, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagentoft, C.-E.; Pallin, S. A conceptual model for how to design for building envelope characteristics. Impact of thermal comfort intervals and thermal mass on commercial buildings in U.S. climates. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brounen, D.; Kok, N.; Quigley, J.M. Residential energy use and conservation: Economics and demographics. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, M.; Kessler, S. Decarbonizing the Building Sector—10 Key Measures; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: http://globalabc.org/resources/publications/decarbonizing-building-sector-10-key-measures (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Estiri, H. A Structural equation model of energy consumption in the United States: Untangling the complexity of per-capita residential energy use. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musall, E.; Weiss, T.; Voss, K.; Lenoir, A.; Donn, M.; Cory, S.; Garde, F. Net Zero Energy Solar Buildings: An Overview and Analysis on Worldwide Building Projects; EuroSun: Graz, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ubinas, E.; Montero, C.; Porteros, M.; Vega, S.; Navarro, I.; Castillo-Cagigal, M.; Matallanas, E.; Gutiérrez, A. Passive design strategies and performance of net energy plus houses. Energy Build 2014, 83, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohanis, Y.G.; Mondol, J.D.; Wright, A.; Norton, B. Real-life energy use in the UK: How occupancy and dwelling characteristics affect domestic electricity use. Energy Build 2008, 40, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcellini, P.; Pless, S.; Deru, M. Zero Energy Buildings: A Critical Look at the Definition. National Renewable Energy Laboratory; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Passivehous Trust. Passivehous: The Route to Zero Carbon? Report. Available online: https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/guidance_detail.php?gId=40 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Alimohammadisagvand, B. Influence of Demand Response Actions on Thermal Comfort and Electricity Cost for Residential Houses. Article Dissertation, Aalto University: Espoo, Finland. 2018. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/33143 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Shaikh, P.H.; Nor, N.B.M.; Nallagownden, P.; Elamvazuthi, I.; Ibrahim, T. Intelligent multi-objective control and management for smart energy efficient buildings. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2016, 74, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Li, W.; Chan, K.W.; Cao, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Smart home energy management systems: Concept, configurations, and scheduling strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2016, 61, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailas, A.; Cecchi, V.; Mukherjee, A. A survey of communications and networking technologies for energy management in buildings and home automation. J. Comput. Netw. Commun. 2012, 2012, 932181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating & Air-Conditioning Engineers. ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals; American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Xia, L.; Pan, S.; Wu, J.; Han, M.; Zhao, X. A review of data-driven approaches for prediction and classification of building energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2018, 82, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M. Simplified 32RC Building Thermal Network Model: A Case Study. Int. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. 2019, 13, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, K.; Jradi, M.; Shaker, H.R.; Veje, C.T. Comparative Analysis of White-, Gray- and Black-Box Models for Thermal Simulation of Indoor Environment: Teaching Building Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2018 Building Performance Modeling Conference and SimBuild, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 September 2018; pp. 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Amara, F.; Agbossou, K.; Cardenas, A.; Dubé, Y.; Kelouwani, S. Comparison and simulation of building thermal models for effective energy management. Smart Grid Renew. Energy 2015, 6, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, D.; Raftery, P.; Keane, M. A review of methods to match building energy simulation models to measured data. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2014, 37, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, Z.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Vega, R. A hybrid model approach for forecasting future residential electricity consumption. Energy Build 2016, 117, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Lund, H.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Leahy, M. A review of computer tools for analysing the integration of renewable energy into various energy systems. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1059–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadian, S.M. Risk Identification in the Early Design Stage Using Thermal Simulations—A Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadian, S.M. Dynamic modelling of solar storage system: A case study of leisure centre. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Hand, J.W.; Kummert, M.; Griffith, B.T. Contrasting the capabilities of building energy performance simulation programs. Build Environ. 2008, 43, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Building Regulations Review of Energy Standards ’Call for Evidence’. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-building-regulations-review-energy-standards-call-evidence/documents/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Hamedani, M.N.; Smith, R. Evaluation of performance modelling: Optimizing simulation tools to stages of architectural design. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, F.; Blight, T.; Natarajan, S.; Shea, A. The use of passive house planning package to reduce energy use and CO2 emissions in historic dwellings. Energy Build 2014, 75, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bros-Williamson, J.; Garnier, C.; Currie, J.I. A longitudinal building fabric and energy performance analysis of two homes built to different energy principles. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, N.; Pearson, A. Ultra-low-energy perspectives for regional Scottish dwellings. Intell. Build. Int. 2013, 5, 221–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Y.; Raslan, R. Variations in results of building energy simulation tools, and their impact on BREEAM and LEED ratings: A case study. Energy Build 2013, 62, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bat, A.M.; Romani, Z.; Bozonnet, E.; Draoui, A. Thermal impact of street canyon microclimate on building energy needs using TRNSYS: A case study of the city of Tangier in Morocco. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 24, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageler, P.; Schweiger, G.; Pichler, M.; Brandl, D.; Mach, T.; Heimrath, R.; Schranzhofer, H.; Hochenauer, C. Validation of dynamic building energy simulation tools based on a Real test-box with thermally activated building systems (TABS). Energy Build 2018, 168, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Ren, P.; Ling, J. Analysis of energy efficiency retrofit scheme for hotel buildings using EQuest software: A case study from Tianjin, China. Energy Build 2015, 87, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, L.; Fabbri, K. Energy performance building evaluation in Mediterranean countries: Comparison between software simulations and operating rating simulation. Energy Build 2008, 40, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usable Buildings. The Building Use Studies (BUS) Occupant Survey: Origins and Approach. Q&A. 2011. Available online: https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/Unprotected/BUSOccupantSurveyQ&A.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Bunn, R.; Marjanovic-Halburd, L. Comfort signatures: How long-term studies of occupant satisfaction in office buildings reveal on-going performance. Build Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 38, 663–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usable Buildings. BUS Occupant Survey Method: Details for Licensees, n.d. Available online: http://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/BUSMethodology.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Huizenga, C.; Zagreus, L.; Arens, E.; Lehrer, D. Measuring Indoor Environmental Quality: A Web-Based Occupant Satisfaction Survey. UC Berkeley: Center for the Built Environment. 2013. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zc5c32z (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Altomonte, S.; Schiavon, S. Occupant satisfaction in LEED and non-LEED certified buildings. Build Environ. 2013, 68, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.T.; Parkinson, T.; Schiavon, S. Lessons learned from 20 Years of CBE’s occupant surveys. B&C 2021, 2, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatioto, A.; Leone, G.; Milone, D.; Pitruzzella, S.; Franzitta, V. Indoor environmental quality survey: A brief comparison between different post occupancy evaluation methods. Adv. Mat. Res. 2014, 864–867, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar]

- AMA WorkWare. Available online: http://aleximarmot.com/workware/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Building Services Research and Information Association (BSRIA). The Soft Landings Framework for Better Briefing, Design, Handover and Building Performance In-Use. 2009. Available online: https://www.usablebuildings.co.uk/UsableBuildings/Unprotected/SoftLandingsFramework.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Stone, A.; Shipworth, D.; Biddulph, P.; Oreszczyn, T. Key factors determining the energy rating of existing English houses. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. Guidance Standard Assessment Procedure. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/standard-assessment-procedure (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Tillson, A.-A.; Oreszczyn, T.; Palmer, J. Assessing impacts of summertime overheating: Some adaptation strategies. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Research Establishment (BRE). The Government’s Standard Assessment Procedure for Energy Rating of Dwellings; BRE: Watford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Killip, G. Can market transformation approaches apply to service markets? An investigation of innovation, learning, risk and reward in the case of low-carbon housing refurbishment in the UK. In Proceedings of the 2011 ECEEE Summer Study on Energy Efficiency: Energy Efficiency First: The Foundation of a Low-Carbon Society, Belambra Presquile de Giens, Belambra Presquile de Giens, France, 6–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gokarakonda, S.; Venjakob, M.; Thomas, S.; Kostova, D. Report on Local EPC Situation and Cross-Country Comparison Matrix. QualDeEPC Project. 2020. Available online: https://qualdeepc.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/QualDeEPC_D2.1_Final_V2.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Kostova, D.; Gokarakonda, S.; Venjakob, M.; Thomas, S. Report on EPC Best Practices. QualDeEPC Project. 2020. Available online: https://qualdeepc.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/QualDeEPC_D2.2-Report-on-EPC-best-practices_Final_28052020.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Gokarakonda, S.; Thomas, S.; Venjakob, M.; Kostova, D. Report on EPC Short Comings and National Priority Approaches to Their Resolution. QualDeEPC Project. 2020. Available online: https://qualdeepc.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/QualDeEPC_D2.3_EPC-shortcomings-and-national-priority-approaches_final-20200422.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Kostova, D.; Thomas, S.; Gokarakonda, S. Development Strategy Plan for the Development of next Generation EPC Schemes. QualDeEPC Project. 2020. Available online: https://qualdeepc.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/QualDeEPC_D2.4-Development-Strategy-plan_200630_final.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Preiser, W.F.E.; Hardy, A.E.; Schramm, U. From linear delivery process to life cycle phases: The validity of the concept of building performance evaluation. In Building Performance Evaluation: From Delivery Process to Life Cycle Phases; Preiser, W.F.E., Hardy, A.E., Schramm, U., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kapsali, M.; Howard, A. Evaluating the influence of building fabric, services and occupant related factors on the actual performance of low energy social housing dwellings in UK. Energy Build 2018, 174, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19208; Framework for Specifying Performance in Buildings. ISO: Vernier, Geneva, 2016.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Post Occupancy Evaluation and Building Performance Evaluation Primer; RIBA: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Low Carbon Building Group. Building Performance Evaluation Research: Testing, Monitoring and Post-Occupancy Evaluation; Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C. Sustainable Renovation Improving Homes for Energy, Health and Environment. The Pebble Trust: Dingwall, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UK Green Building Council. Delivering Building Performance; UK Green Building Council: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UK Green Building Counci. Practical How-to Guide: How to: Execute a High Impact Post Occupancy Evaluation, n.d; UK Green Building Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Froese, T.M.; Brager, G. Post-occupancy evaluation: State-of-the-art analysis and state-of-the-practice review. Build Environ. 2018, 133, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, W.F.E.; White, E.; Rabinowitz, H. Post-Occupancy Evaluation (Routledge Revivals), 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Learning from Our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, S. Post-occupancy evaluation of UK library building projects: Some examples of current activity. LIBER Q. 2002, 12, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Building Knowledge: Pathways to Post Occupancy Evaluation; RIBA: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- HEFCE; AUDE; University of Westminster. Guide to Post Occupancy Evaluation. 2006. Available online: http://www.smg.ac.uk/documents/POEBrochureFinal06.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Jafari, A.; Valentin, V. An optimization framework for building energy retrofits decision-making. Build Environ. 2017, 115, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Status Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Xia, X.; Zhang, J. A Multi-objective optimization model for the life-cycle cost analysis and retrofitting planning of buildings. Energy Build. 2014, 77, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, A.G.; Gabrielli, L.; Scarpa, M. Energy retrofit in European building portfolios: A review of five key aspects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashempour, N.; Taherkhani, R.; Mahdikhani, M. Energy performance optimization of existing buildings: A literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy; Department for Communities and Local Government. Each Home Counts. An Independent Review of Consumer Advice, Protection, Standards and Enforcement for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. 2016. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/578749/Each_Home_Counts__December_2016_.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- PAS 2035/2030; 2019 Retrofitting Dwellings for Improved Energy Efficiency. Specification and Guidance. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2019.

- Jones, P.; Li, X.; Perisoglou, E.; Patterson, J. Five energy retrofit houses in South Wales. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. Altering existing buildings in the UK. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4482–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Saving Trust. Domestic Energy Primer—An Introduction to Energy Efficiency in Existing Home. 2006. Available online: https://www.southend.gov.uk/downloads/file/416/energy-efficiency-introductory-guide (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Baeli, M. Residential Retrofit: Twenty Case Studies; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Whiffen, T.; Pasquale, L.; National Energy Foundation. Energy efficiency—Technology Landscaping; Scotland’s Energy Efficiency Programme: 2017. Available online: https://www.climatexchange.org.uk/media/1331/technology_landscaping_report_energy_efficiency_technologies.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Almeida, M.; Ferreira, M. Cost effective energy and carbon emissions optimization in building renovation (Annex 56). Energy Build. 2017, 152, 718–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, H.; Steemers, K. Energy retrofit and occupant behaviour in protected housing: A case study of the Brunswick Centre in London. Energy Build. 2014, 80, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, A. BREEAM—History and Future; Building Research Establishment: Watford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Building Research Establishment. BREEAM Scheme Document SD 5052; Building Research Establishment: Watford, UK , 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, A. Briefing: BREEAM 2008: Moving beyond excellence. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. -Civ. Eng. 2008, 161, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Research Establishment. BREEAM 2011 FAQs. Available online: https://tools.breeam.com/filelibrary/BREEAM%202011/BREEAM_2011FAQs_6.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Building Research Establishment. Global BREEAM 2011. Open Letter and Summary Paper. Available online: https://tools.breeam.com/filelibrary/BREEAM%202011/BREEAM_2011_Open_letter_and_summary_paper_PDF.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Sezer, A. Environmental assessment tools and efficiency in housing and office refurbishment. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ARCOM Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 September 2012; Smith, S.D., Ed.; Association of Researchers in Construction Management; pp. 1331–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, R.; Xiao, H. Is BREEAM suitable for small and medium refurbishment/maintenance projects? In Proceedings of the 48th ASC Annual International Conference, Birmingham, UK, 11–14 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Building Research Establishment. BREEAM New Construction 2018 (UK). Available online: https://www.breeam.com/NC2018/#01_introduction_newcon/2introductiontobreeam_nc.htm%3FTocPath%3DIntroduction%2520to%2520BREEAM%7C_____0 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Parker, J. The Value of BREEAM; BSRIA: Bracknell, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doggart, J.; Baldwin, D.R. BREEAM international: Regional similarities and differences of an international strategy for environmental assessment of buildings. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference: Buildings and the Environment, Paris, France, 9–12 June 1997; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, I.A.S.; Zhang, X. Green building rating systems in Swedish market—A comparative analysis between LEED, BREEAM SE, GreenBuilding and Miljöbyggnad. Energy Procedia 2018, 153, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubba, S. Chapter 2—Basic LEEDTM concepts. In LEED Practices, Certification, and Accreditation Handbook; Kubba, S., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Green Building Council. Green Building Rating System for New Construction & Major Renovations (LEED-NC), Version 2.1. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/sites/default/files/LEEDv2.1RS%204-8-03.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Steelcase. Understanding LEED Version 3. Available online: https://www.steelcase.com/content/uploads/2015/05/understanding_leed_version_31.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- U.S. Green Building Council. LEED v4, the Newest Version of LEED Green Building Program Launches at USGBC’s Annual Greenbuild Conference. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/leed-v4-newest-version-leed-green-building-program-launches-usgbc%E2%80%99s-annual-greenbuild-confe (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- U.S. Green Building Council. LEED v4 Impact Category and Point Allocation Process Overview. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/resources/leed-v4-impact-category-and-point-allocation-process-overview (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- U.S. Green Building Council. LEED v4.1 Building Design and Construction. Getting Started Guide for Beta Participants; U.S. Green Building Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scofield, J.H. Do LEED-certified buildings save energy? Not really… Energy Build. 2009, 41, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H. Efficacy of LEED-certification in reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emission for large New York city office buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 67, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | U-Values (W/m2K) For Each Updates of “Part L—Conservation of Fuel and Power” | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 Target Emission Rate (TER) Introduced | 2013 Target Fabric Energy Efficiency (TFEE) Introduced | Consultation Version, January 2021 Target Primary Energy Rate Introduced | |

| Roof | 0.20–0.25 1 | 0.16–0.25 2 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| Exposed walls | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.26 |

| Exposed floor and ground floors | 0.35–0.45 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.18 |

| Semi-exposed walls and floors | 0.6 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Windows, doors, and rooflights | 3.0–3.3 1 | 2.0-2.2 3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | Windows and doors 1.6 Rooflight 2.2 |

| Air permeability | - | - | - | 10 m3/(hm2) at 50 Pa | 10 m3/(hm2) at 50 Pa | 8 m3/(hm2) at 50 Pa |

| MethodMethod | Techniques Used | Focus | When | Length of the Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Montfort Method | Walk through the building | Process review, functional performance | 1 year after occupancy | 1 day |

| Design Quality Indicators | Online questionnaire | Quality of the building | Design stage and after completion | 20–30 min |

| Overall Linking Score | Online/hard copy questionnaire | Users’ satisfaction | 1 year after occupancy | 10–12 min per person |

| PROBE | Questionnaire, focus groups, energy, and space audits | Users’ satisfaction and systems performance | Time suggested after 1 year | From 2 days to over a month |

| BUS Occupant Survey | Questionnaire, walk through the building | Users’ satisfaction | Time suggested after 1 year | 10–15 min per person |

| Energy Assessment and Reporting Methodology | Energy use survey | Energy saved | After building completion | Up to 1 person per week |

| Learning from Experience | Group discussions | Process review | During the whole construction process, or at the end | 1 seminar, or continuous evaluation |

| 1910 | 1975 | 1995 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space Heating | 63% | 44% | 33% |

| Hot Water | 16% | 25% | 25% |

| Lighting | 17% | 25% | 34% |

| Cooking | 4% | 6% | 8% |

| BREEAM Rating | % Score |

|---|---|

| Outstanding | ≥85 |

| Excellent | ≥70 |

| Very good | ≥55 |

| Good | ≥45 |

| Pass | ≥30 |

| Rating System | Category |

|---|---|

| LEED for New Construction | Green Building Design and Construction |

| LEED for Core and Shell | |

| LEED for School | |

| LEED for Healthcare | |

| LEED for Retail | |

| LEED for Commercial Interiors | Green Interior Design and Construction |

| LEED for Retail Interiors | |

| LEED for Existing Buildings | Green Buildings Operations and Maintenance |

| LEED for Existing Schools | |

| LEED for Neighbourhood Development | Green Neighbourhood Development |

| LEED for Homes | Green Home Design and Construction |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seminara, P.; Vand, B.; Sajjadian, S.M.; Tupenaite, L. Assessing and Monitoring of Building Performance by Diverse Methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031242

Seminara P, Vand B, Sajjadian SM, Tupenaite L. Assessing and Monitoring of Building Performance by Diverse Methods. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031242

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeminara, Paola, Behrang Vand, Seyed Masoud Sajjadian, and Laura Tupenaite. 2022. "Assessing and Monitoring of Building Performance by Diverse Methods" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031242

APA StyleSeminara, P., Vand, B., Sajjadian, S. M., & Tupenaite, L. (2022). Assessing and Monitoring of Building Performance by Diverse Methods. Sustainability, 14(3), 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031242