Structure-Based Virtual Screening and In Silico Evaluation of Marine Algae Metabolites as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Validation of Molecular Docking Protocol

2.2. Virtual Screening Analysis

2.3. Drug-Likeness and ADME-Tox Profile Assessment

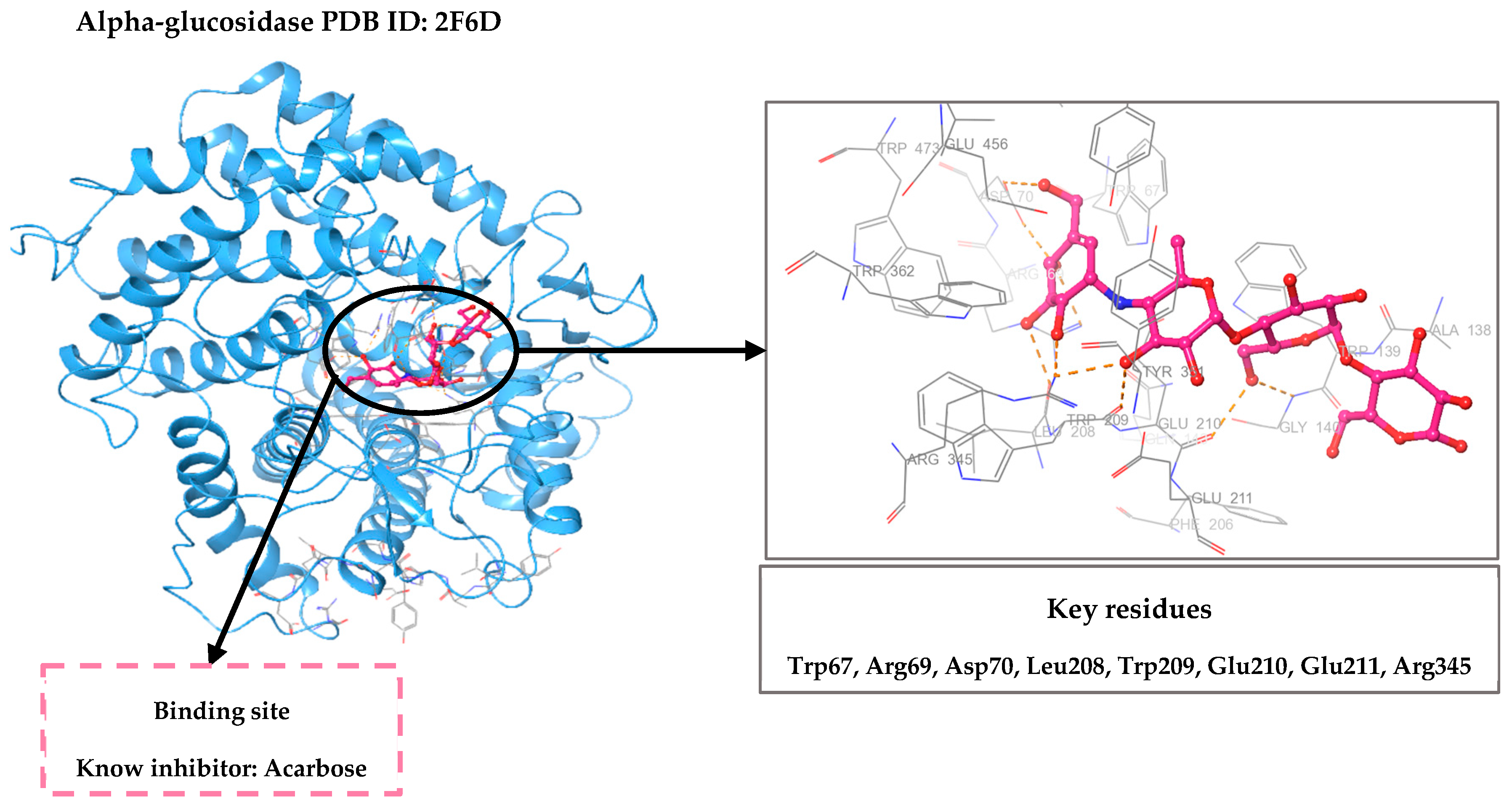

2.4. Protein–Ligand Interactions Analysis

2.5. DFT Study

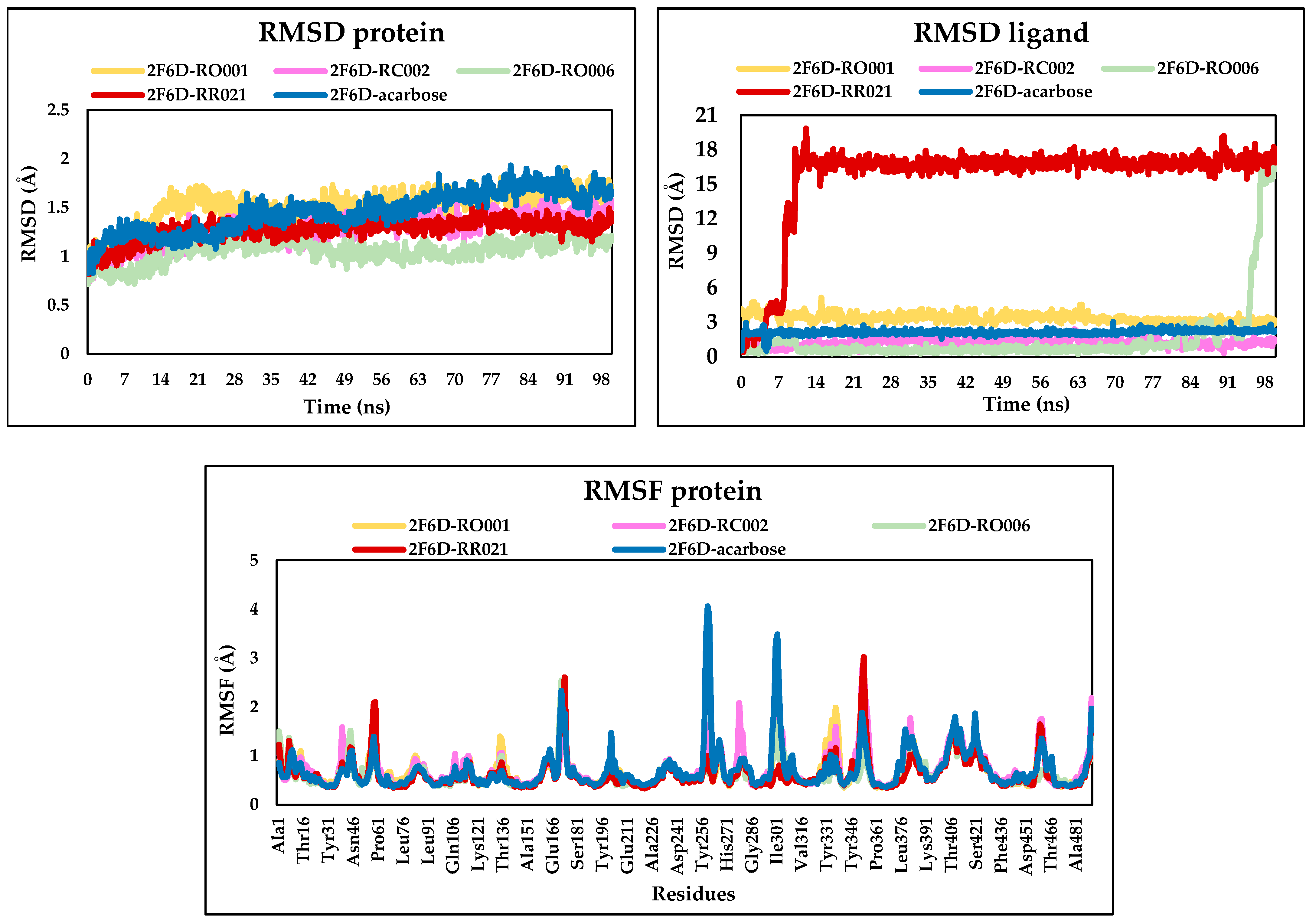

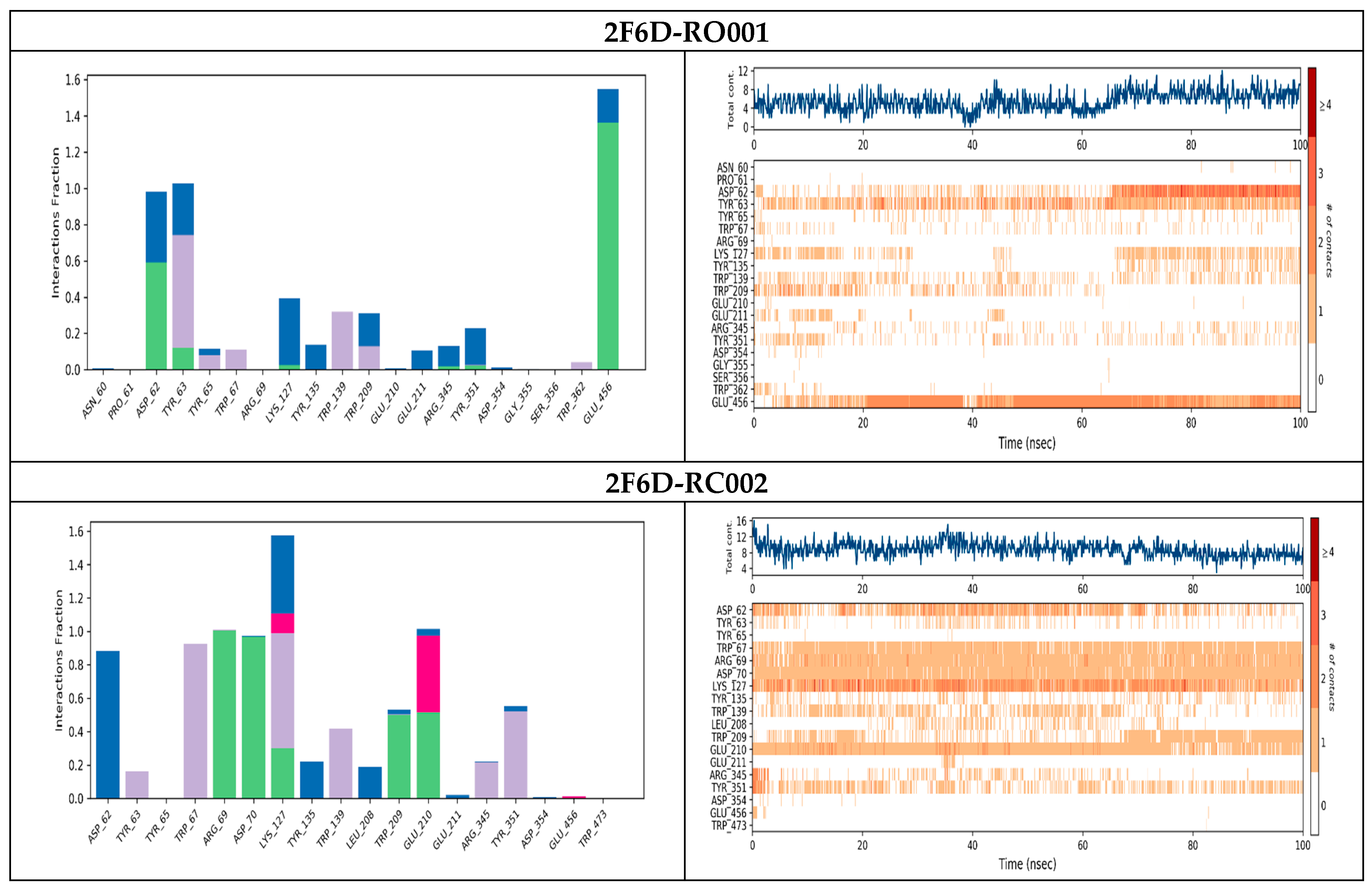

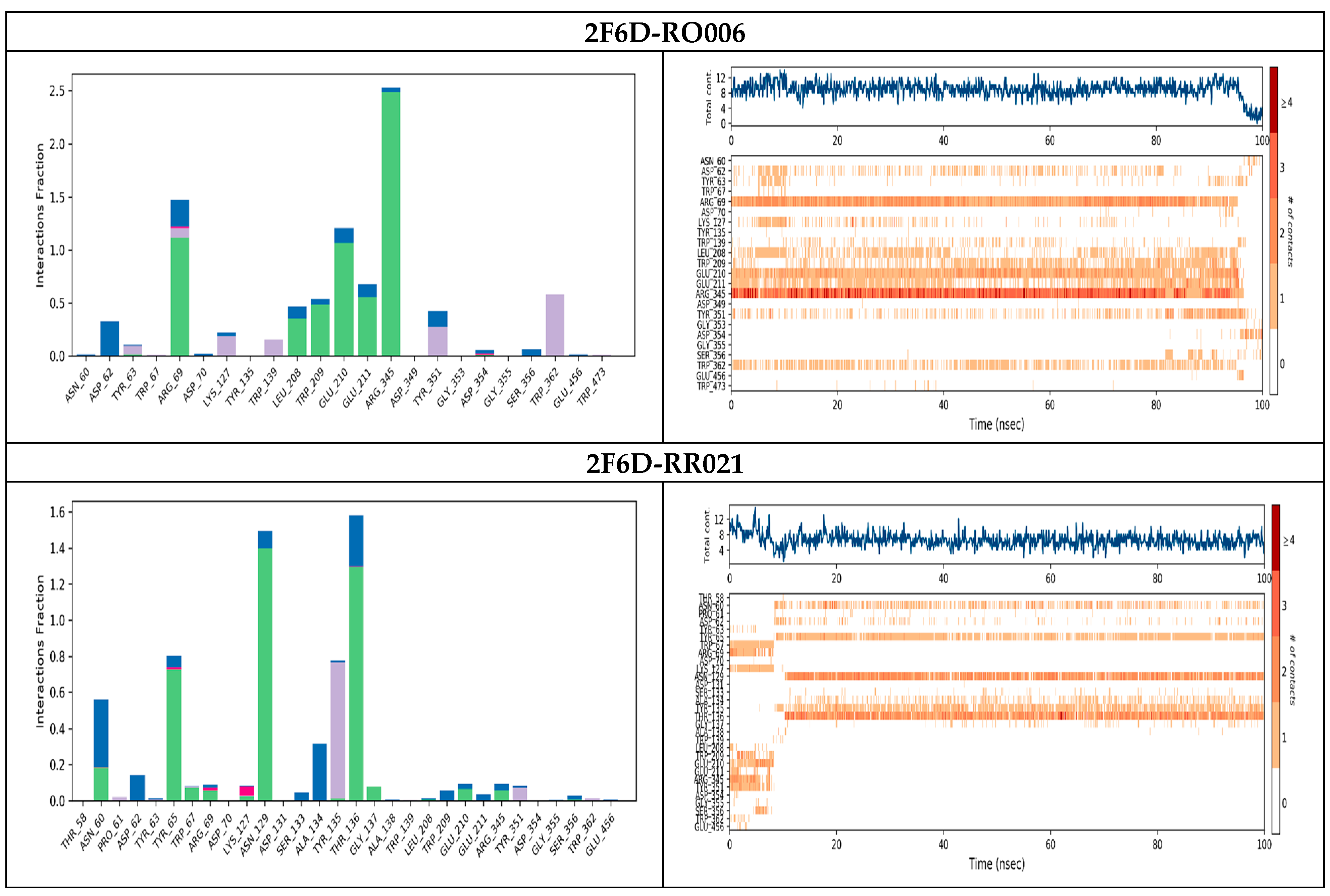

2.6. Molecular Dynamics Analysis

2.7. Limitations of the Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Preparation of Ligands

3.3. Selection and Preparation of Protein

3.4. Molecular Docking

3.5. Drug-likeness and ADMET Filtering

3.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3.7. DFT Calculations

| Ionization potential | Electron affinity | Energy gap |

| IP = −EHOMO | EA = −ELUMO | ΔE= ELUMO − EHOMO |

| Hardness | Softness | Electronegativity |

| η = (IP − EA)/2 | σ = 1/η | χ = (IP + EA)/2 |

| Chemical potential | Electrophilicity index | |

| μ = − χ | ω = μ2/2η | |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; McCoy, R.G.; Aleppo, G.; Balapattabi, K.; Beverly, E.A. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S27–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossafi, B.; Abchir, O.; El Kouali, M.; Chtita, S. Advancements in Computational Approaches for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery: A Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 1123–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameny, A.A. Diabetes Mellitus Overview 2024. J. Biosci. Appl. Res. 2024, 10, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Aroda, V.R.; Collins, B.S.; Gabbay, R.A.; Green, J.; Maruthur, N.M.; Rosas, S.E.; Del Prato, S.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2753–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.d.J.; Al-Mamun Md Islam, M.d.R. Diabetes mellitus, the fastest growing global public health concern: Early detection should be focused. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhefnawy, M.E.; Ghadzi, S.M.S.; Noor Harun, S. Predictors Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Complications over Time: A Literature Review. J. Vasc. Dis. 2022, 1, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abchir, O.; Yamari, I.; Shtaiwi, A.M.; Nour, H.; Kouali, M.E.; Talbi, M.; Chtita, S. Insights into the inhibitory potential of novel hydrazinyl thiazole-linked indenoquinoxaline against alpha-amylase: A comprehensive QSAR, pharmacokinetic, and molecular modeling study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 43, 5701–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; ElSayed, N.A.; McCoy, R.G.; Aleppo, G.; Balapattabi, K.; Beverly, E.A.; Early, K.B.; Bruemmer, D.; Callaghan, B.C.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; et al. 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S252–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossafi, B.; Bouribab, A.; Abchir, O.; Khedraoui, M.; El Kouali, M.; Chtita, S. Antidiabetic potential of Moroccan medicinal plant extracts: A virtual screening using in silico approaches. Results Chem. 2025, 16, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldan, A.; Bouamrane, S.; El-Mernissi, R.; Maghat, H.; Ajana, M.; Sbai, A.; Bouachrine, M.; Lakhlifi, T. In silico design of new α-glucosidase inhibitors through 3D-QSAR study, molecular docking modeling and ADMET analysis. Mor. J. Chem. 2022, 10, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, T.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, F. Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Peptides: Sources, Preparations, Identifications, and Action Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clissold, S.P.; Edwards, C. Acarbose: A Preliminary Review of its Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Properties, and Therapeutic Potential. Drugs 1988, 35, 214–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumaran, K.; Janagili, M.; Rajana, N.; Papureddy, S.; Anireddy, J. Development and Validation of Miglitol and Its Impurities by RP-HPLC and Characterization Using Mass Spectrometry Techniques. Sci. Pharm. 2016, 84, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebovitz, H.E. Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 26, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirir, A.M.; Daou, M.; Yousef, A.F.; Yousef, L.F. A review of alpha-glucosidase inhibitors from plants as potential candidates for the treatment of type-2 diabetes. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1049–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdigaliyev, N.; Aljofan, M. An Overview of Drug Discovery and Development. Future Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.B.; Lee, K.Y. Integrative metabolomics and system pharmacology reveal the antioxidant blueprint of Psoralea corylifolia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento IJdos, S. Applied Computer-Aided Drug Design: Models and Methods; Bentham Science Publishers: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mekkanti, M.R.; Rinku, M. A Review on Computer Aided Drug Design (Caad) and It’s Implications in Drug Discovery and Development Process. Int. J. Health Care Biol. Sci. 2020, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. The Science and Art of Structure-Based Virtual Screening. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, J.; Luttens, A. Structure-based virtual screening of vast chemical space as a starting point for drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2024, 87, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.B.; Baiseitova, A.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.H.; Park, K.H. Analogues of Dihydroflavonol and Flavone as Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibitors from the Leaves of Artocarpus elasticus. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 9053–9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, M.N.; de Sousa, D.S.; da Silva Mendes, F.R.; dos Santos, H.S.; Marinho, G.S.; Marinho, M.M.; Marinho, E.S. Ligand and structure-based virtual screening approaches in drug discovery: Minireview. Mol. Divers. 2025, 29, 2799–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtita, S.; Fouedjou, R.T.; Belaidi, S.; Djoumbissie, L.A.; Ouassaf, M.; Qais, F.A.; Bakhouch, M.; Efendi, M.; Tok, T.T.; Bouachrine, M.; et al. In silico investigation of phytoconstituents from Cameroonian medicinal plants towards COVID-19 treatment. Struct. Chem. 2022, 33, 1799–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yu, S.; Zhou, M.; Wang, P.; Li, W.; Jin, X.; Pan, Y.; Sheng, Y.; Li, H.; Qin, L.; et al. Diterpenoids of Marine Organisms: Isolation, Structures, and Bioactivities. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamani, M.; Melnychuk, T.; Eisenhauer, A.; Gäbler, R.; Schultz, C. Investigating Past, Present, and Future Trends on Interface Between Marine and Medical Research and Development: A Bibliometric Review. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.-G.; Chang, Y.-C.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Lo, Y.-H.; Chi, W.-C.; Zhang, M.M.; Tsou, L.K.; Wen, Z.-H.; Hwang, T.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; et al. Systematic Review of Natural Briaranes in Marine Organisms (2020–2024): Chemical Structures and Bioactivities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2025, 73, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesco, K.C.; Williams, S.K.R.; Laurens, L.M.L. Marine Algae Polysaccharides: An Overview of Characterization Techniques for Structural and Molecular Elucidation. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Avni, D.; Varela, J.; Barreira, L. The Ocean’s Pharmacy: Health Discoveries in Marine Algae. Molecules 2024, 29, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.; Mayer, V.; Swanson-Mungerson, M.; Pierce, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Nakamura, F.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Marine Pharmacology in 2019–2021: Marine Compounds with Antibacterial, Antidiabetic, Antifungal, Anti-Inflammatory, Antiprotozoal, Antituberculosis and Antiviral Activities; Affecting the Immune and Nervous Systems, and Other Miscellaneous Mechanisms of Action. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banday, A.H.; Azha, N.U.; Farooq, R.; Sheikh, S.A.; Ganie, M.A.; Parray, M.N.; Mushtaq, H.; Hameed, I.; Lone, M.A. Exploring the potential of marine natural products in drug development: A comprehensive review. Phytochem. Lett. 2024, 59, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, H.; Salhy, A.; Rossafi, B.; Mounadi, N.; Chtita, S. Identification of Potent Hepcidin Antagonists for Anemia Treatment: An In Silico Drug Repositioning Study. Phys. Chem. Res. 2025, 13, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, F.; Demirpolat, A.; Kazachenko, A.S.; Kazachenko, A.S.; Issaoui, N.; Al-Dossary, O. Molecular Structure, Electronic Properties, Reactivity (ELF, LOL, and Fukui), and NCI-RDG Studies of the Binary Mixture of Water and Essential Oil of Phlomis bruguieri. Molecules 2023, 28, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.D.J.; Vasanthi, A.H.R. Seaweed metabolite database (SWMD): A database of natural compounds from marine algae. Bioinformation 2011, 5, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, K.; Wu, C.; Damm, W.; Reboul, M.; Stevenson, J.M.; Lu, C.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Mondal, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; et al. OPLS3e: Extending Force Field Coverage for Drug-Like Small Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerguer, F.Z.; Rossafi, B.; Abchir, O.; Raouf, Y.S.; Albalushi, D.B.; Samadi, A.; Chtita, S. Potential Azo-8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives as multi-target lead candidates for Alzheimer’s disease: An in-depth in silico study of monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibitors. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ševčík, J.; Hostinová, E.; Solovicová, A.; Gašperík, J.; Dauter, Z.; Wilson, K.S. Structure of the complex of a yeast glucoamylase with acarbose reveals the presence of a raw starch binding site on the catalytic domain. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.E.; Montgomery, P.A. Acarbose: An α-glucosidase inhibitor. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 1996, 53, 2277–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.D.; Friedman, A.J.; Rogers, K.E.; McCammon, J.A. Comparing Neural-Network Scoring Functions and the State of the Art: Applications to Common Library Screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 1726–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalekshmi, V.; Balakrishnan, N.; Ajay Kumar, T.V.; Parthasarathy, V. In Silico Molecular Screening and Docking Approaches on Antineoplastic Agent-Irinotecan Towards the Marker Proteins of Colon Cancer. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2023, 15, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestro. Schrödinger n.d. Available online: https://www.schrodinger.com/platform/products/maestro/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Mark, P.; Nilsson, L. Structure and Dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E Water Models at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 9954–9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossafi, B.; Abchir, O.; Guerguer, F.Z.; Khedraoui, M.; Kouali, M.E.; Chtita, S. Integrated Computational Approach for Designing Novel Pyridone-Based α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: Insights From 2D-QSAR, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulations, and MM-GBSA Analysis. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e02869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Yang, W. Challenges for Density Functional Theory. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 289–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, A.; Ramazani, A. Using Gaussian and GaussView software for effective teaching of chemistry by drawing molecules. Res. Chem. Educ. 2024, 6, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M. Gaussian 09, Revision d. 01; Gaussian. Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.W.; Gill, P.M.W.; Nobes, R.H.; Radom, L. 6-31IG(MC)(d,p): A Second-Row Analogue of the 6-31IG(d,p) Basis Set. Calculated Heats of Formation for Second-Row Hydrides. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 4875–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, E.E.; Richards, W.G. Molecular similarity based on electrostatic potential and electric field. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1987, 32, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | Name | Source | Structure | XP Score (kcal/mol) | Molecule | Name | Source | Structure | XP Score (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

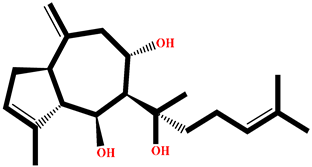

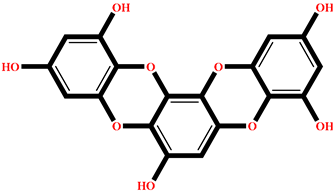

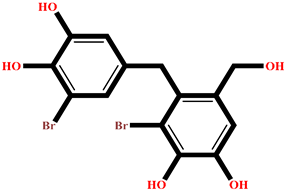

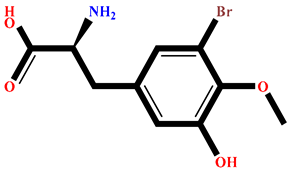

| RO001 | Colensolide A | Osmundaria colensoi |  | −10.58 | BD008 | 8α,11-dihydroxypachydictyol A | Dictyota sp. |  | −8.459 |

| BE013 | Eckstolon | Ecklonia stolonifera |  | −9.708 | GA001 | 5-hydroxyisoavrainvilleol | Avrainvillea nigricans |  | −8.367 |

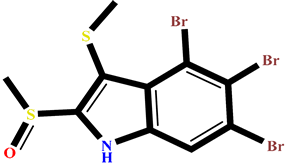

| RR023 | (2S)-2-amino-3-(3-bromo-5-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid | Rhodomela confervoides |  | −9.304 | RL495 | 2-methylsulfinyl-3-methylthio-4,5,6-tribromoindole | Laurencia brongniartii |  | −8.233 |

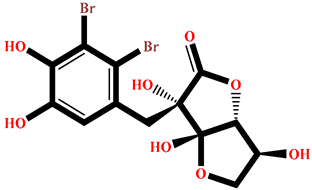

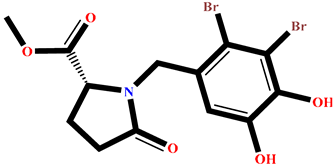

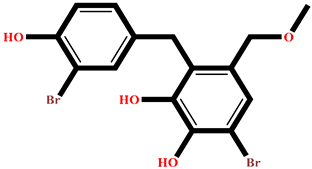

| RO006 | Rhodomelol | Osmundaria colensoi |  | −8.817 | RR016 | N-(2,3-Dibromo-4,5-dihydroxybenzyl)methyl pyroglutamate | Rhodomela confervoides |  | −8.163 |

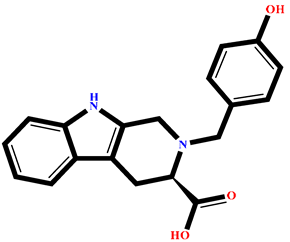

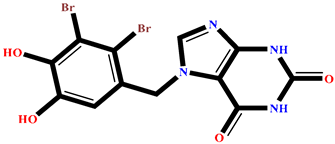

| RC002 | Callophycin A | Callophycus oppositifolius |  | −8.493 | RR021 | 7-(2,3-dibromo-4,5-dihydroxybenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione | Rhodomela confervoides |  | −8.113 |

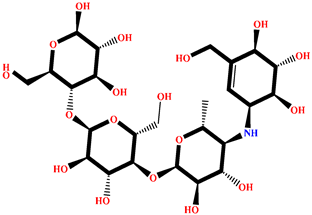

| GA009 | Avrainvilleol methyl ether | Avrainvillea rawsonii |  | −8.462 | Reference drug | Acarbose | --- |  | −12.33 |

| Molecule | QPlogPo/w | QLogS | QLogHERG | QPPCaco | QLogBB | QLogKp | PSA | Rule of Five | Rule of Three |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO001 | 0.952 | −2.505 | −4.93 | 40.40 | −0.79 | −6.38 | 110.72 | 0 | 0 |

| BE013 | 0.825 | −3.546 | −5.847 | 26.89 | −2.39 | −4.95 | 141.37 | 0 | 0 |

| RR023 | −1.168 | −1.438 | −2.40 | 11.44 | −0.75 | −6.17 | 101.45 | 0 | 1 |

| RO006 | 0.030 | −2.585 | −3.73 | 48.51 | −1.68 | −5.17 | 146.16 | 0 | 0 |

| RC002 | 0.730 | −3.811 | −4.66 | 18.06 | −0.82 | −5.03 | 86.91 | 0 | 1 |

| GA009 | 3.164 | −4.212 | −4.74 | 692.88 | −0.63 | −2.57 | 69.93 | 0 | 0 |

| BD008 | 3.779 | −4.363 | −4.22 | 2154.73 | −0.49 | −1.84 | 49.94 | 0 | 1 |

| GA001 | 1.373 | −2.974 | −4.29 | 72.11 | −1.64 | −4.52 | 105.52 | 0 | 0 |

| RL495 | 3.357 | −3.343 | −4.11 | 104.45 | 0.44 | −2.19 | 33.49 | 0 | 0 |

| RR016 | 0.903 | −1.913 | −1.94 | 144.31 | −0.88 | −3.98 | 100.97 | 0 | 0 |

| RR021 | 0.425 | −3.105 | −3.88 | 27.91 | −1.71 | −5.77 | 143.99 | 0 | 0 |

| Molecule | RO001 | BE013 | RR023 | RO006 | RC002 | GA009 | BD008 | GA001 | RL495 | RR016 | RR021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C13H15Br2N3O4 | C18H10O9 | C10H12BrNO4 | C13H12Br2O8 | C19H18N2O3 | C15H14Br2O4 | C20H32O3 | C14H12Br2O5 | C10H8Br3NOS2 | C13H13Br2NO5 | C12H8Br2N4O4 |

| MW | 437.08 | 370.27 | 290.11 | 456.04 | 322.36 | 418.08 | 320.47 | 420.05 | 462.02 | 423.05 | 432.02 |

| Rotatable bonds | 3 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| H-bond acceptors | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| H-bond donors | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Log P | 1.26 | 2.05 | −1.25 | 0.02 | 1.79 | 3.01 | 2.85 | 2.21 | 3.76 | 1.53 | 1.05 |

| GI absorption | High | Low | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| BBB permeant | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Lipinski violations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bioavailability Score | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Synthetic Accessibility | 3.46 | 3.48 | 2.41 | 4.09 | 2.96 | 2.73 | 5.39 | 2.59 | 3.09 | 2.68 | 2.28 |

| Molecule | Toxicity Risk | Drug Likeness | Drug Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic | Tumorigenic | Irritant | Reproductive Effective | |||

| RO001 |  |  |  |  | 2.35 | 0.75 |

| BE013 |  |  |  |  | −1.28 | 0.21 |

| RR023 |  |  |  |  | −10.96 | 0.47 |

| RO006 |  |  |  |  | −0.43 | 0.55 |

| RC002 |  |  |  |  | 2.44 | 0.85 |

| GA009 |  |  |  |  | −2.59 | 0.35 |

| BD008 |  |  |  |  | −2.6 | 0.24 |

| GA001 |  |  |  |  | −2.74 | 0.39 |

| RL495 |  |  |  |  | −1.13 | 0.2 |

| RR016 |  |  |  |  | −1.27 | 0.49 |

| RR021 |  |  |  |  | 2.98 | 0.75 |

| No risk |  | Moderate risk |  | High risk | |

| Complex | XP Score (kcal/mol) | Involved Residues | Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2F6D-RO001 | −10.580 | Arg69, Asp70, Glu210, Glu211, Glu456 | Hydrogen bond |

| 2F6D-RO006 | −8.817 | Arg69, Asp70, Leu208, Trp209, Glu210, Glu211 | Hydrogen bond |

| 2F6D-RC002 | −8.493 | Arg69, Asp70, Glu210 Trp139 | Hydrogen bond π–π stacking |

| 2F6D-RR021 | −8.113 | Arg69, Asp70, Leu208, Glu211, Arg345 | Hydrogen bond |

| 2F6D-Acarbose | −12.330 | Arg69, Asp70, Gly140, Leu208, Trp209, Glu210, Glu211 | Hydrogen bond |

| Molecules | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | ΔE (eV) | χ (eV) | η (eV) | µ (eV) | σ (eV−1) | ω (eV) | Dipol Moment (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO001 | −6.054 | −0.696 | 5.358 | 3.375 | 2.679 | −3.375 | 0.373 | 2.125 | 8.463 |

| RO006 | −5.871 | −0.476 | 5.395 | 3.174 | 2.698 | −3.174 | 0.371 | 1.867 | 7.864 |

| RC002 | −5.529 | −0.329 | 5.200 | 2.929 | 2.600 | −2.929 | 0.385 | 1.650 | 5.081 |

| RR021 | −6.090 | −1.086 | 5.004 | 3.588 | 2.502 | −3.588 | 0.400 | 2.572 | 7.560 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rossafi, B.; Abchir, O.; Guerguer, F.; Abass, K.S.; Yamari, I.; El Kouali, M.; Samadi, A.; Chtita, S. Structure-Based Virtual Screening and In Silico Evaluation of Marine Algae Metabolites as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010098

Rossafi B, Abchir O, Guerguer F, Abass KS, Yamari I, El Kouali M, Samadi A, Chtita S. Structure-Based Virtual Screening and In Silico Evaluation of Marine Algae Metabolites as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleRossafi, Bouchra, Oussama Abchir, Fatimazahra Guerguer, Kasim Sakran Abass, Imane Yamari, M’hammed El Kouali, Abdelouahid Samadi, and Samir Chtita. 2026. "Structure-Based Virtual Screening and In Silico Evaluation of Marine Algae Metabolites as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010098

APA StyleRossafi, B., Abchir, O., Guerguer, F., Abass, K. S., Yamari, I., El Kouali, M., Samadi, A., & Chtita, S. (2026). Structure-Based Virtual Screening and In Silico Evaluation of Marine Algae Metabolites as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Antidiabetic Drug Discovery. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010098