In Vivo Study of Osseointegrable Bone Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Implants Coated with a Vanillin Derivative

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

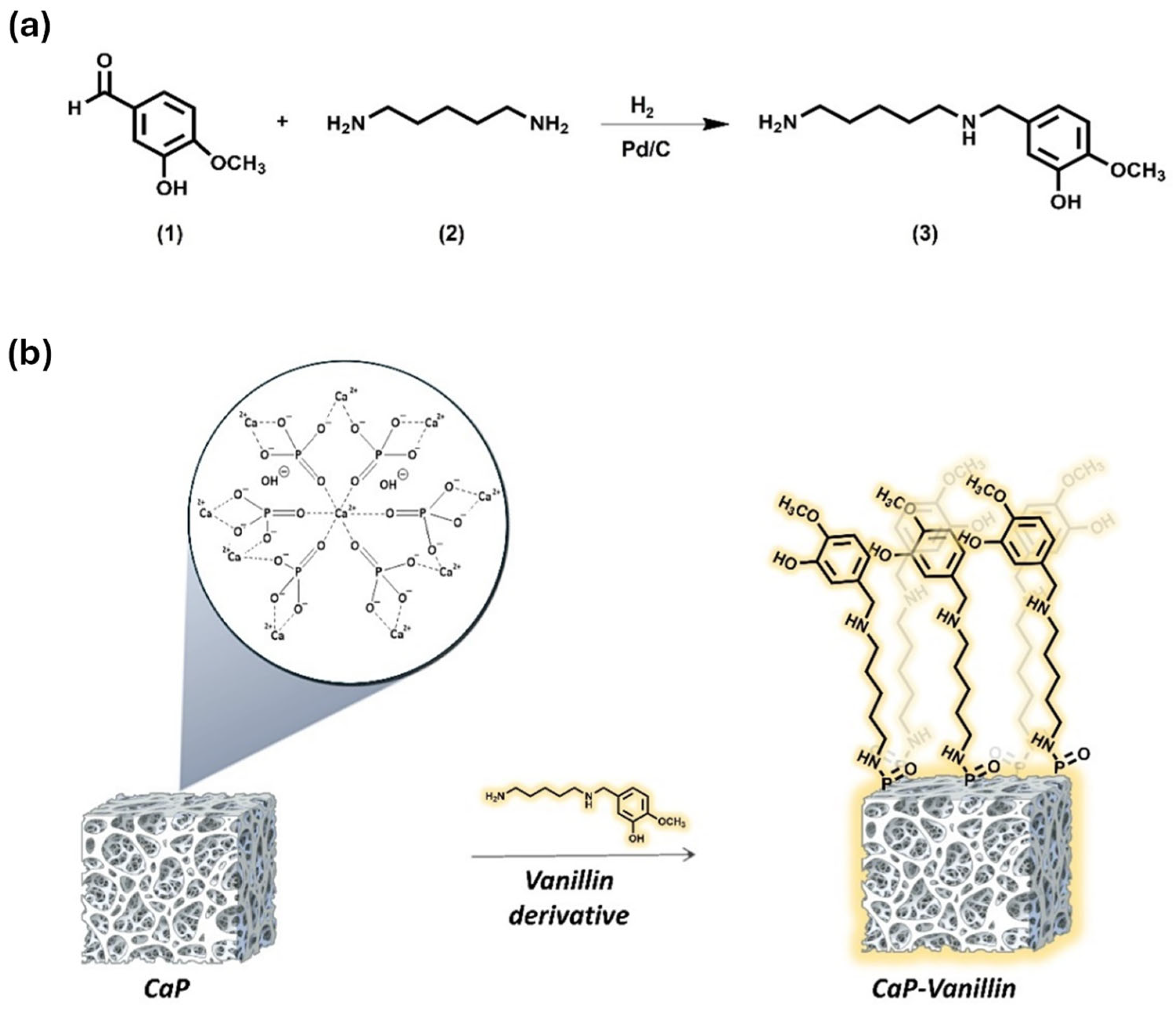

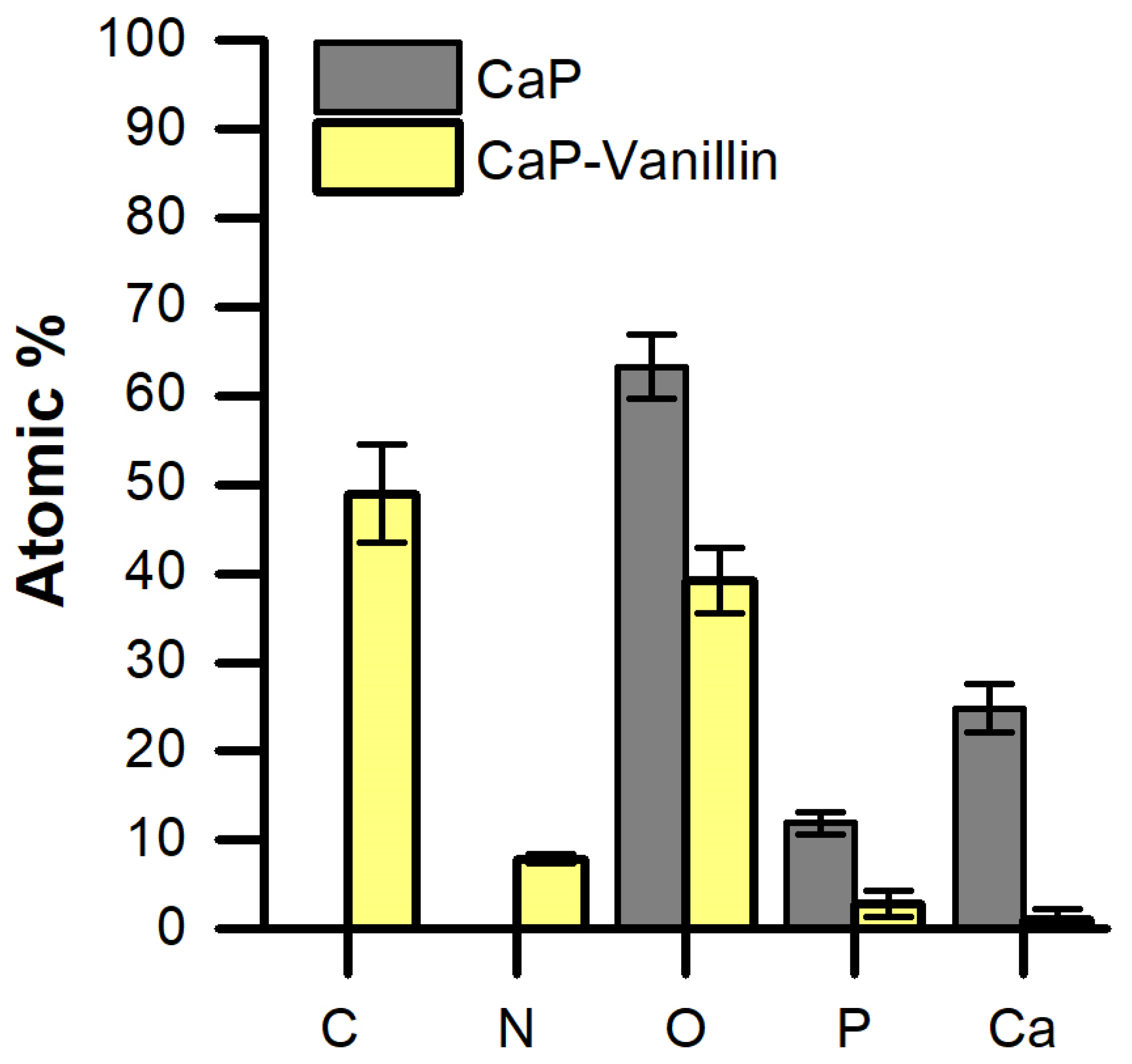

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the Functionalized CaP Material

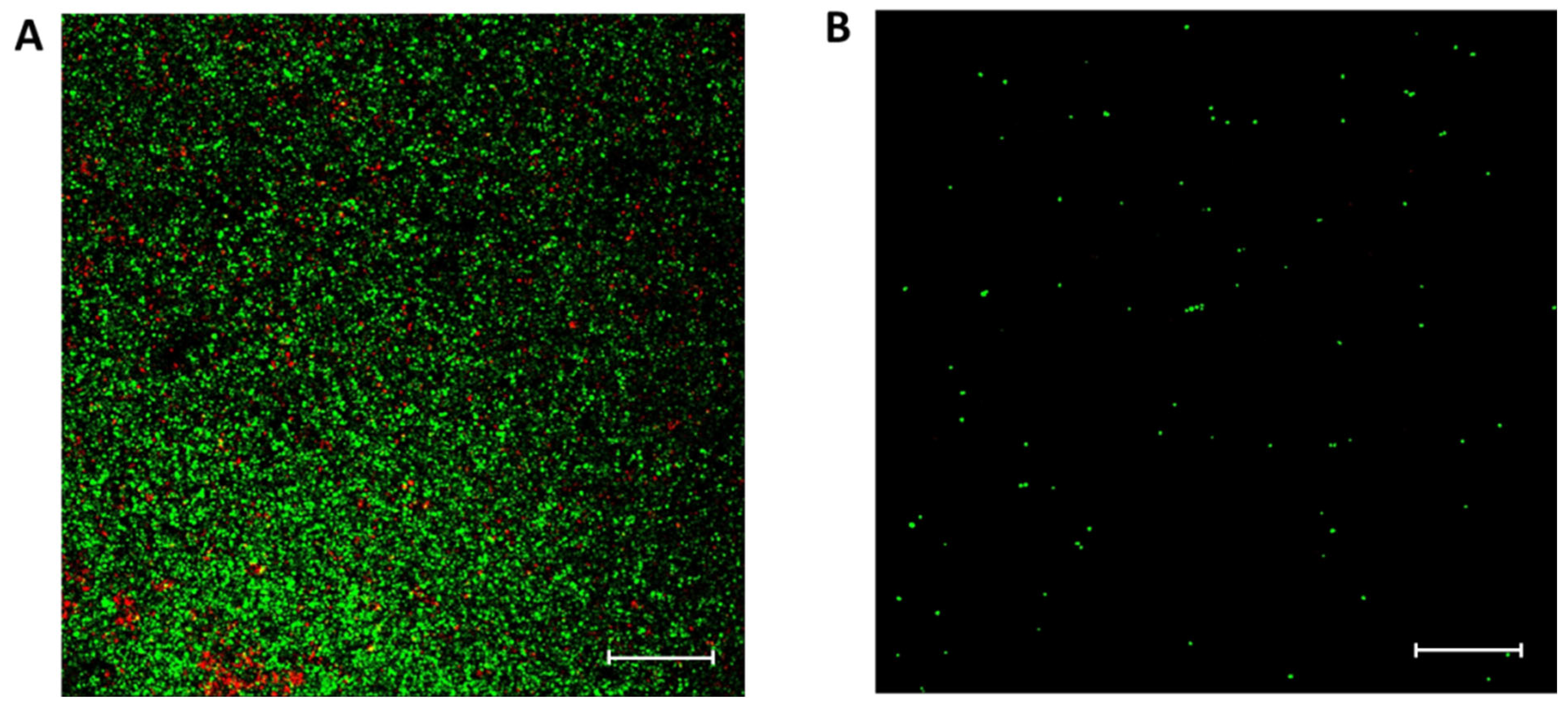

2.2. Antibacterial Capacity of CaP Material Functionalized with Vanillin

2.3. Antibiofilm Capacity of CaP Material Functionalized with Vanillin

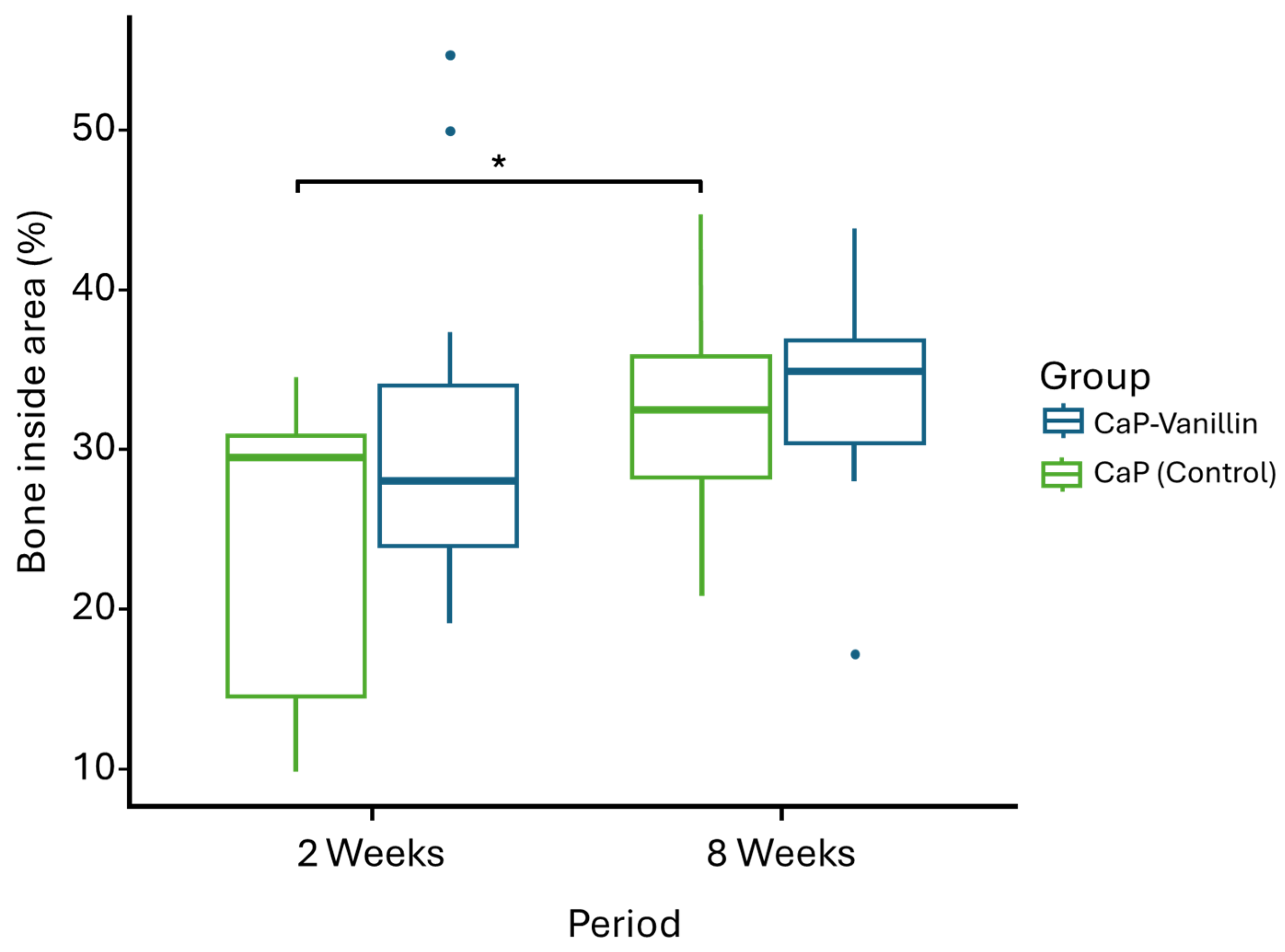

2.4. In Vivo Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents, Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions

3.2. Synthesis of Vanillin Derivative (3)

3.3. Preparation of CaP Functionalised with Vanillin Derivative (CaP-Vanillin)

3.4. Characterization Methods

3.5. Antibacterial Activity

3.5.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assays

3.5.2. Biofilm Formation Assays

3.5.3. Scanning Confocal Laser Microscopy

3.6. In Vivo Study

3.7. Histological Evaluation and Explanted Distal Femurs Histomorphometric Measurements

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hench, L.L.; Thompson, I. Twenty-first century challenges for biomaterials. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, S379–S391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daculsi, G. Biphasic calcium phosphate concept applied to artificial bone, implant coating and injectable bone substitute. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baino, F.; Novajra, G.; Vitale-Brovarone, C. Bioceramics and scaffolds: A winning combination for tissue engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Diefenbeck, M.; Mcnally, M. Ceramic Biocomposites as Biodegradable Antibiotic Carriers in the Treatment of Bone Infections. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2017, 2, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N.; Metoki, N. Calcium phosphate bioceramics: A review of their history, structure, properties, coating technologies and biomedical applications. Materials 2017, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattimani, V.S.; Kondaka, S.; Lingamaneni, K.P. Hydroxyapatite–-Past, Present, and Future in Bone Regeneration. Bone Tissue Regen. Insights 2016, 7, BTRI-S36138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskoković, V.; Wu, V.M. Calcium phosphate as a key material for socially responsible tissue engineering. Materials 2016, 9, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huzum, B.; Puha, B.; Necoara, R.; Gheorghevici, S.; Puha, G.; Filip, A.; Sirbu, P.; Alexa, O. Biocompatibility assessment of biomaterials used in orthopedic devices: An overview (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, J.M.; Mait, J.E.; Unnanuntana, A.; Hirsch, B.P.; Shaffer, A.D.; Shonuga, O.A. Materials in Fracture Fixation. In Comprehensive Biomaterials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.H.; Ben-Nissan, B.; Conway, R.C.; Macha, I.J. Advances in Calcium Phosphate Nanocoatings and Nanocomposites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 485–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, K.; Wolke, J.G.C.; Jansen, J.A. Calcium phosphate coatings for medical implants. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 1998, 212, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, J.; Cordero-Ampuero, J. Treatment of prosthetic osteoarticular infections. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2011, 12, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, W.L.; Della Valle, C.J.; Iorio, R.; Berend, K.R.; Cushner, F.D.; Dalury, D.F.; Lonner, J.H. Complications of total knee arthroplasty: Standardized list and definitions of the knee society knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciola, C.R.; Visai, L.; Testoni, F.; Arciola, S.; Campoccia, D.; Speziale, P.; Montanaro, L. Concise survey of Staphylococcus aureus virulence factors that promote adhesion and damage to peri-implant tissues. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 34, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tande, A.J.; Patel, R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 302–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mohler, J.; Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Bruggemann, L.; Aalinkeel, R. Microbial Biofilm: A Review on Formation, Infection, Antibiotic Resistance, Control Measures, and Innovative Treatment. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widerström, M.; Stegger, M.; Johansson, A.; Gurram, B.K.; Larsen, A.R.; Wallinder, L.; Edebro, H.; Monsen, T. Heterogeneity of Staphylococcus epidermidis in prosthetic joint infections: Time to reevaluate microbiological criteria? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 41, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomizawa, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Bello-Irizarry, S.N.; de Mesy Bentley, K.L.; Ito, H.; Kates, S.L.; Daiss, J.L.; Beck, C.; Matsuda, S.; Schwarz, E.M.; et al. Biofilm Producing Staphylococcus epidermidis (RP62A Strain) Inhibits Osseous Integration Without Osteolysis and Histopathology in a Murine Septic Implant Model. J. Orthop. Res. 2020, 38, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarch-Pérez, C.; Riool, M.; de Boer, L.; Kloen, P.; Zaat, S.A.J. Bacterial reservoir in deeper skin is a potential source for surgical site and biomaterial-associated infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 140, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severn, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus epidermidis and its dual lifestyle in skin health and infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzana, J.A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. Biomaterials approaches to treating implant-associated osteomyelitis. Biomaterials 2016, 81, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, N.; Galiana, I.; Hurtado, S.; Mondragón, L.; Bernardos, A.; Sancenón, F.; Marcos, M.D.; Amorós, P.; Abril-Utrillas, N.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; et al. Enhanced antifungal efficacy of tebuconazole using gated pH-driven mesoporous nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, L.; Gómez-Cerezo, N.; Aznar, E.; Vivancos, J.L.; Sancenón, F.; Arcos, D.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Martínez-Máñez, R. Molecular gates in mesoporous bioactive glasses for the treatment of bone tumors and infection. Acta Biomater. 2017, 50, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadekuzzaman, M.; Yang, S.; Mizan, M.F.R.; Ha, S.D. Current and Recent Advanced Strategies for Combating Biofilms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freires, I.; Denny, C.; Benso, B.; de Alencar, S.; Rosalen, P. Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils and Their Isolated Constituents against Cariogenic Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 7329–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-González, M.L.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Aguilar, C.N. Essential Oils: A Natutal Alternative to Combat Antibiotics Resistance. In Antibiotic Resistance, Mechanisms and New Antimicrobial Approaches; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, D. Plant-derived antimicrobial compounds: Alternatives to antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassolé, I.H.N.; Juliani, H.R. Essential Oils in Combination and Their Antimicrobial Properties. Molecules 2012, 17, 3989–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Dhanasekaran, D.K.; Zeb, F.; Faris, M.E.; Naja, F.; Radwan, H.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Hasan, H.; Hashim, M.; Obaid, R.S. A Status Review on Health-Promoting Properties and Global Regulation of Essential Oils. Molecules 2023, 28, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardos, A.; Bozik, M.; Alvarez, S.; Saskova, M.; Perez-Esteve, E.; Kloucek, P.; Lhotka, M.; Frankova, A.; Martinez-Manez, R. The efficacy of essential oil components loaded into montmorillonite against Aspergillus niger and Staphylococcus aureus. Flavour Fragr. J. 2019, 34, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S. Mediating bone regeneration by means of drug eluting implants: From passive to smart strategies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, D.; Torricelli, P.; Gentilomi, G.A.; Boanini, E.; Gazzano, M.; Bonvicini, F.; Benetti, E.; Soldati, R.; Martelli, G.; Rubini, K.; et al. Monocyclic β-lactams loaded on hydroxyapatite: New biomaterials with enhanced antibacterial activity against resistant strains. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, N.; Arcos, D.; Polo, L.; Aznar, E.; Sánchez-Salcedo, S.; Sancenón, F.; García, A.; Marcos, M.D.; Baeza, A.; Vallet-Regí, M.; et al. Towards the Development of Smart 3D “Gated Scaffolds” for On-Command Delivery. Small 2014, 10, 4859–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribes, S.; Ruiz-Rico, M.; Pérez-Esteve, É.; Fuentes, A.; Talens, P.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Barat, J.M. Eugenol and thymol immobilised on mesoporous silica-based material as an innovative antifungal system: Application in strawberry jam. Food Control 2017, 81, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rico, M.; Pérez-Esteve, É.; Bernardos, A.; Sancenón, F.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Marcos, M.D.; Barat, J.M. Enhanced antimicrobial activity of essential oil components immobilized on silica particles. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.; Teixeira, P.; Oliveira, R. Mini-review: Staphylococcus epidermidis as the most frequent cause of nosocomial infections: Old and new fighting strategies. Biofouling 2014, 30, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebuhr, W.; Hennig, S.; Eckart, M.; Kränzler, H.; Batzilla, C.; Kozitskaya, S. Nosocomial infections by Staphylococcus epidermidis: How a commensal bacterium turns into a pathogen. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2006, 28, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, V.; Causa, F.; Netti, P.A.; Ciapetti, G.; Pagani, S.; Martini, D.; Baldini, N.; Ambrosio, L. The role of hydroxyapatite as solid signal on performance of PCL porous scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 86, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenbasi, N.; Kalyon, D.M.; Birinci, E. Biocomposites of nanohydroxyapatite with collagen and poly(vinyl alcohol). Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2006, 48, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, J.S.; Meehan, J.P.; Di Cesare, P.E.; Jamali, A.A. Local antibiotic therapy in osteomyelitis. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 23, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConoughey, S.J.; Howlin, R.; Granger, J.F.; Manring, M.M.; Calhoun, J.H.; Shirtliff, M.; Kathju, S.; Stoodley, P. Biofilms in periprosthetic orthopedic infections. Future Microbiol. 2014, 9, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, S.S.; Rookes, J.E.; Cahill, D.M.; Lenka, S.K. Vanillin: A review on the therapeutic prospects of a popular flavouring molecule. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, C.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M.; Ruiz, M.J. Relevant essential oil components: A minireview on increasing applications and potential toxicity. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2021, 31, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héquet, A.; Humblot, V.; Berjeaud, J.-M.; Pradier, C.-M. Optimized grafting of antimicrobial peptides on stainless steel surface and biofilm resistance tests. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 84, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska, J.M.; Genoud, K.J.; Kelly, D.J.; O’Brien, F.J. Bone biomaterials for overcoming antimicrobial resistance: Advances in non-antibiotic antimicrobial approaches for regeneration of infected osseous tissue. Mater. Today 2021, 46, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boanini, E.; Cassani, M.; Rubini, K.; Boga, C.; Bigi, A. (9R)-9-Hydroxystearate-Functionalized Anticancer Ceramics Promote Loading of Silver Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silingardi, F.; Bonvicini, F.; Cassani, M.C.; Mazzaro, R.; Rubini, K.; Gentilomi, G.A.; Bigi, A.; Boanini, E. Hydroxyapatite Decorated with Tungsten Oxide Nanoparticles: New Composite Materials against Bacterial Growth. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, A.; Chaudhari, V.S.; Kushram, P.; Bose, S. 3D Printed SiO2 –Tricalcium Phosphate Scaffolds Loaded with Carvacrol Nanoparticles for Bone Tissue Engineering Application. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.P.N.; Arango-Ospina, M.; Oliveira, R.L.M.S.; Ferreira, I.M.; de Moraes, E.G.; Hartmann, M.; de Oliveira, A.P.N.; Boccaccini, A.R.; de Sousa Trichês, E. 3D-printed β-TCP/S53P4 bioactive glass scaffolds coated with tea tree oil: Coating optimization, in vitro bioactivity and antibacterial properties. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallukka, M.; Gamna, F.; Gobbo, V.A.; Prato, M.; Najmi, Z.; Cochis, A.; Rimondini, L.; Ferraris, S.; Spriano, S. Surface Functionalization of Ti6Al4V-ELI Alloy with Antimicrobial Peptide Nisin. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Jahani, A.; Moradi, A.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.H.; Jirofti, N. Different Modification Methods of Poly Methyl Methacrylate (PMMA) Bone Cement for Orthopedic Surgery Applications. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2023, 11, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegre, M.; Poljańska, E.; Caetano, L.A.; Gonçalves, L.; Bettencourt, A. Research progress on biodegradable polymeric platforms for targeting antibiotics to the bone. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 648, 123584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, R.A.; Kim, H.-W.; Ginebra, M.-P. Polymeric additives to enhance the functional properties of calcium phosphate cements. J. Tissue Eng. 2012, 3, 204173141243955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeching, N.J.; Thomas, M.G.; Roberts, S.; Lang, S.D.R. Comparative in-vitro activity of antibiotics incorporated in acrylic bone cement. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1986, 17, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-L.; Li, Y.-F.; Fang, T.-L.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-C.; Dong, J. Vancomycin-loaded nano-hydroxyapatite pellets to treat MRSA-induced chronic osteomyelitis with bone defect in rabbits. Inflamm. Res. 2012, 61, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Zuo, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Morsi, Y.S. Gentamicin-impregnated chitosan/nanohydroxyapatite/ethyl cellulose microspheres granules for chronic osteomyelitis therapy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 93, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amna, T.; Alghamdi, A.A.A.; Shang, K.; Hassan, M.S. Nigella Sativa-Coated Hydroxyapatite Scaffolds: Synergetic Cues to Stimulate Myoblasts Differentiation and Offset Infections. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, L.; Díaz de Greñu, B.; Della Bella, E.; Pagani, S.; Torricelli, P.; Vivancos, J.L.; Ruiz-Rico, M.; Barat, J.M.; Aznar, E.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of commercial calcium phosphate based materials functionalized with vanillin. Acta Biomater. 2018, 81, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.-M.; Kim, E.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Park, K.-R. Vanillin Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation, Mineral Apposition, and Antioxidant Effects in Pre-Osteoblasts. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadrazilova, I.; Pospisilova, S.; Pauk, K.; Imramovsky, A.; Vinsova, J.; Cizek, A.; Jampilek, J. In Vitro Bactericidal Activity of 4- and 5-Chloro-2-hydroxy-N-[1-oxo-1-(phenylamino)alkan-2-yl]benzamides against MRSA. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 49534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Comparison Factor | Mean ± SD (%) | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | Mean Difference (Effect Size) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 weeks: CaP vs. CaP-Vanillin | 30.65 ± 11.13 vs. 23.48 ± 9.25 | [−15.82, 1.50] | −7.16 | 0.101 |

| 8 weeks: CaP vs. CaP-Vanillin | 33.05 ± 7.11 vs. 31.56 ± 7.24 | [−7.56, 4.59] | −1.48 | 0.618 |

| Temporal CaP: 2w vs. 8w | 30.65 ± 11.13 vs. 33.05 ± 7.11 | [−11.45, 6.64] | 2.40 | 0.535 |

| Temporal CaP-Vanillin: 2w vs. 8w | 23.48 ± 9.25 vs. 31.56 ± 7.24 | [0.98, 15.18] | 8.08 | 0.0263 |

| 2 Weeks | 8 Weeks | |

|---|---|---|

| CaP group | 6 samples | 6 samples |

| CaP-Vanillin group | 6 samples | 6 samples |

| TOTAL | 12 samples (6 animals) | 12 samples (6 animals) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Medaglia, S.; Bernabé-Quispe, P.; Tomás-Chenoll, J.; Cebriá-Mendoza, M.; Tormo-Mas, M.Á.; Primo-Capella, V.J.; Bernardos, A.; Marcos, M.D.; Peris-Serra, J.L.; Aznar, E.; et al. In Vivo Study of Osseointegrable Bone Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Implants Coated with a Vanillin Derivative. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010091

Medaglia S, Bernabé-Quispe P, Tomás-Chenoll J, Cebriá-Mendoza M, Tormo-Mas MÁ, Primo-Capella VJ, Bernardos A, Marcos MD, Peris-Serra JL, Aznar E, et al. In Vivo Study of Osseointegrable Bone Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Implants Coated with a Vanillin Derivative. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedaglia, Serena, Patricia Bernabé-Quispe, Julia Tomás-Chenoll, María Cebriá-Mendoza, María Ángeles Tormo-Mas, Víctor Javier Primo-Capella, Andrea Bernardos, María Dolores Marcos, José Luis Peris-Serra, Elena Aznar, and et al. 2026. "In Vivo Study of Osseointegrable Bone Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Implants Coated with a Vanillin Derivative" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010091

APA StyleMedaglia, S., Bernabé-Quispe, P., Tomás-Chenoll, J., Cebriá-Mendoza, M., Tormo-Mas, M. Á., Primo-Capella, V. J., Bernardos, A., Marcos, M. D., Peris-Serra, J. L., Aznar, E., & Martínez-Máñez, R. (2026). In Vivo Study of Osseointegrable Bone Calcium Phosphate (CaP) Implants Coated with a Vanillin Derivative. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010091