Mechanistic Evaluation of Roxadustat for Pulmonary Fibrosis: Integrating Network Pharmacology, Transcriptomics, and Experimental Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result

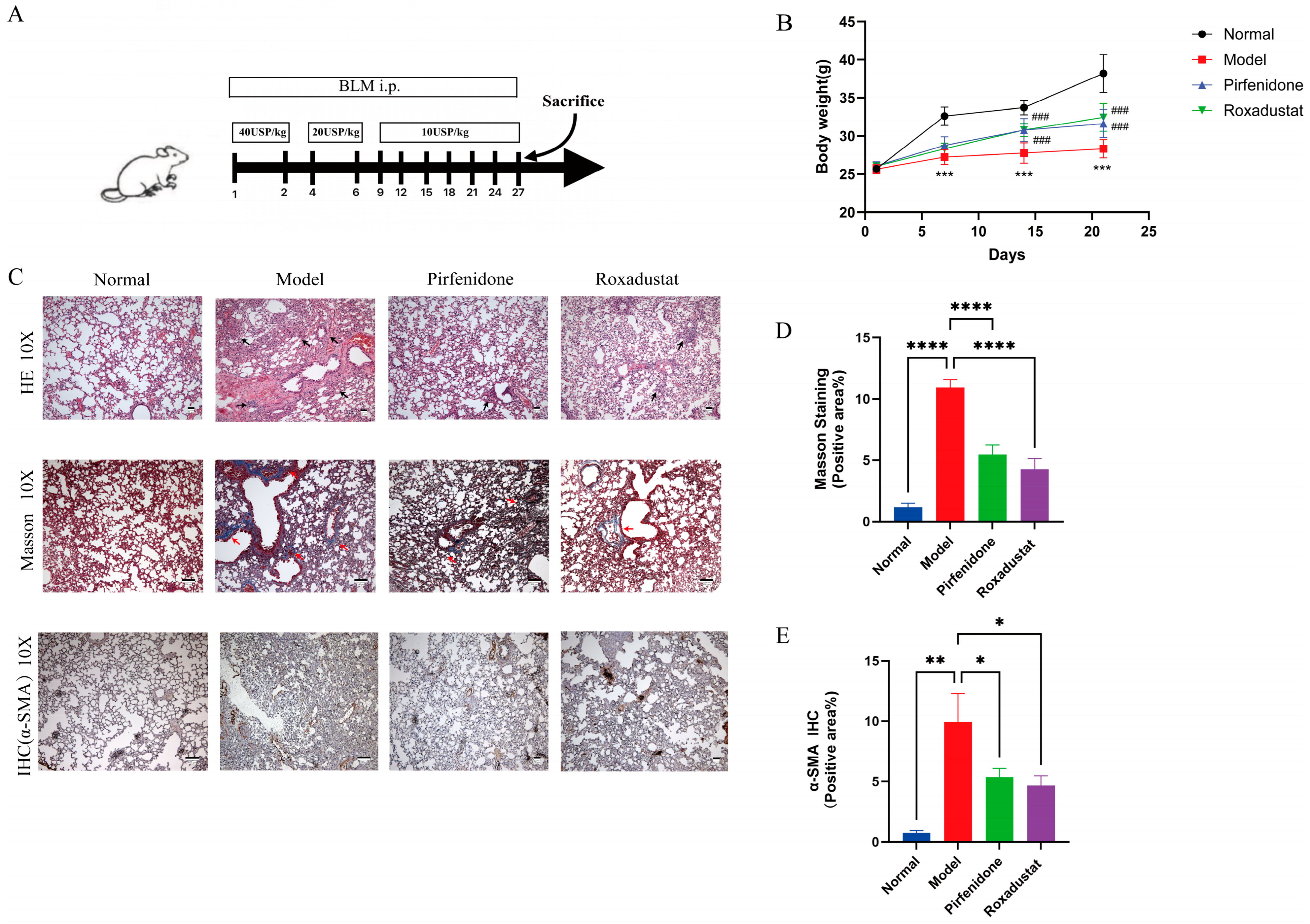

2.1. Roxadustat Improves Lung Tissue Metabolism in Mice with PF

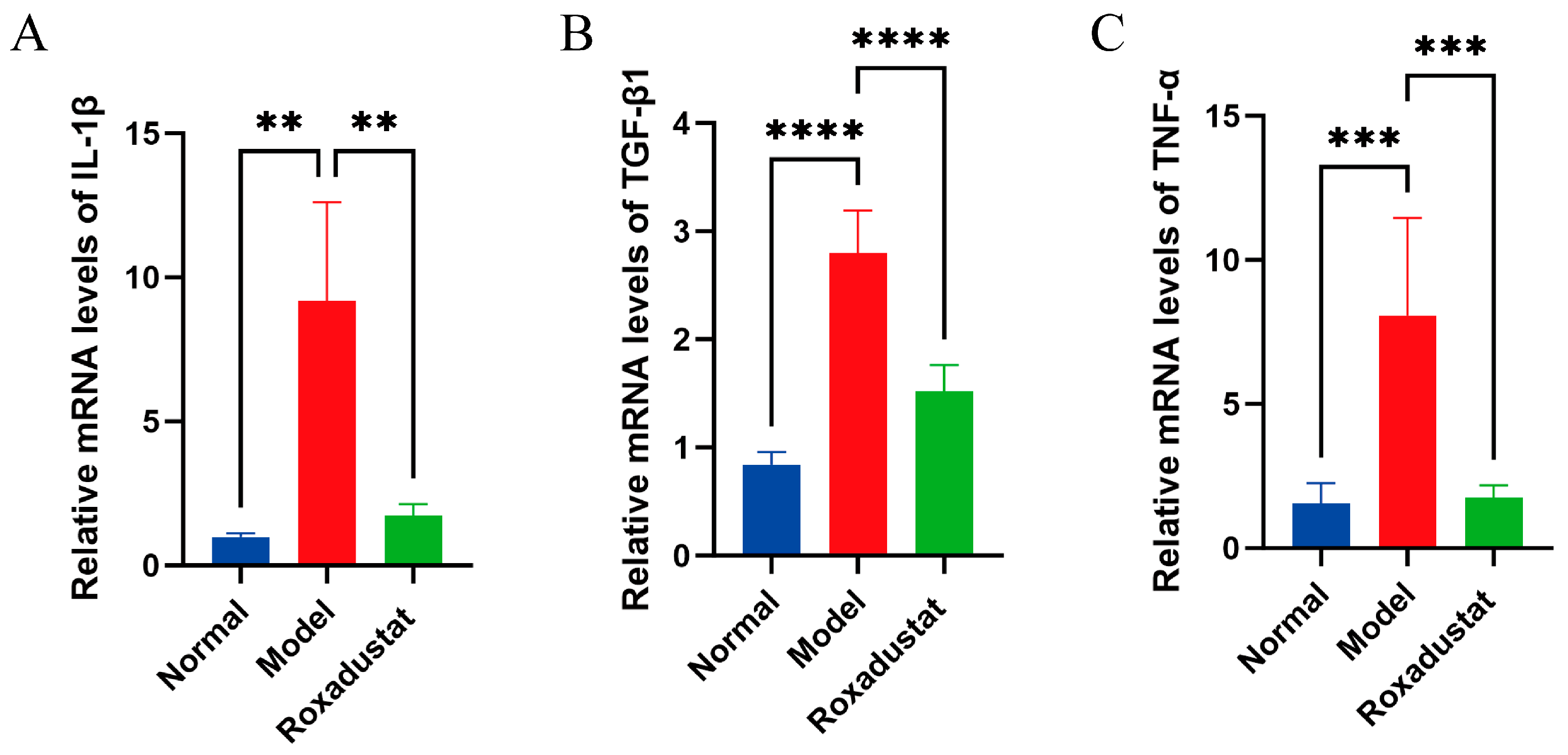

2.2. Roxadustat Reduces Inflammation in Mice Lung Tissue

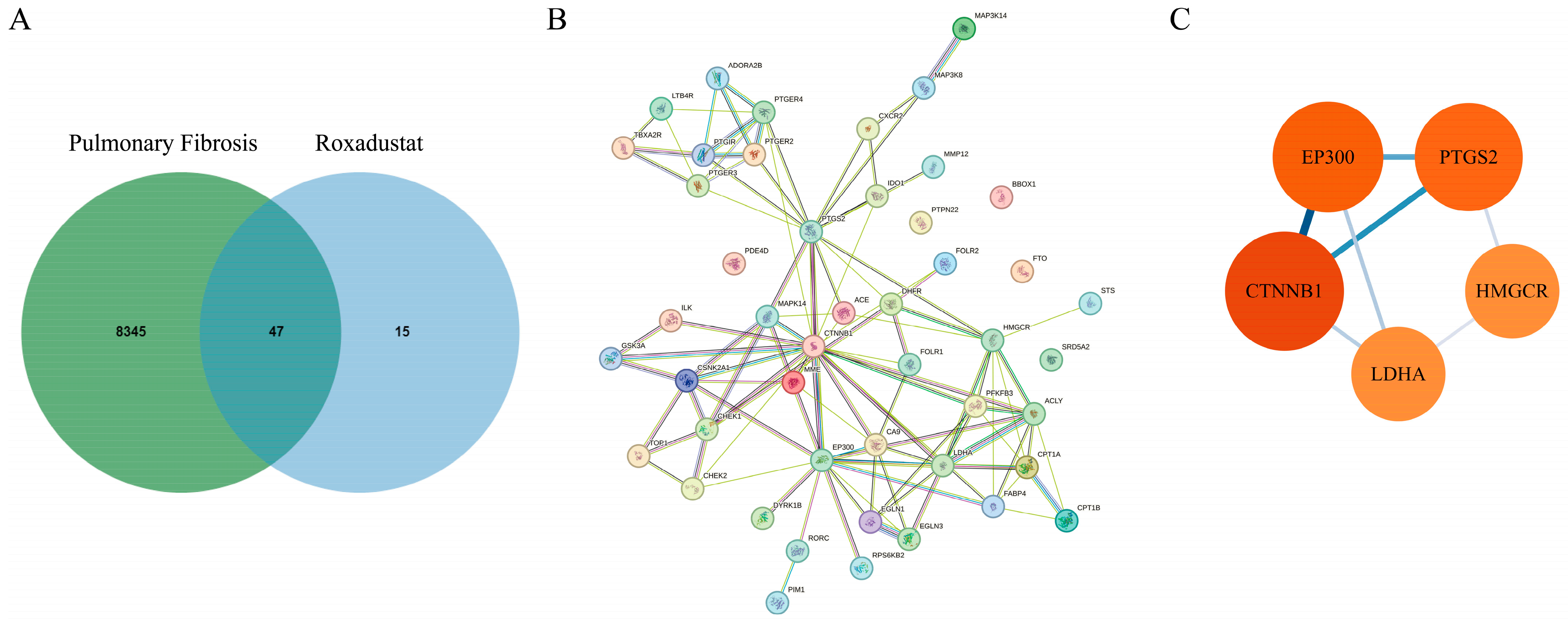

2.3. Identification of Roxadustat Targets in PF Treatment

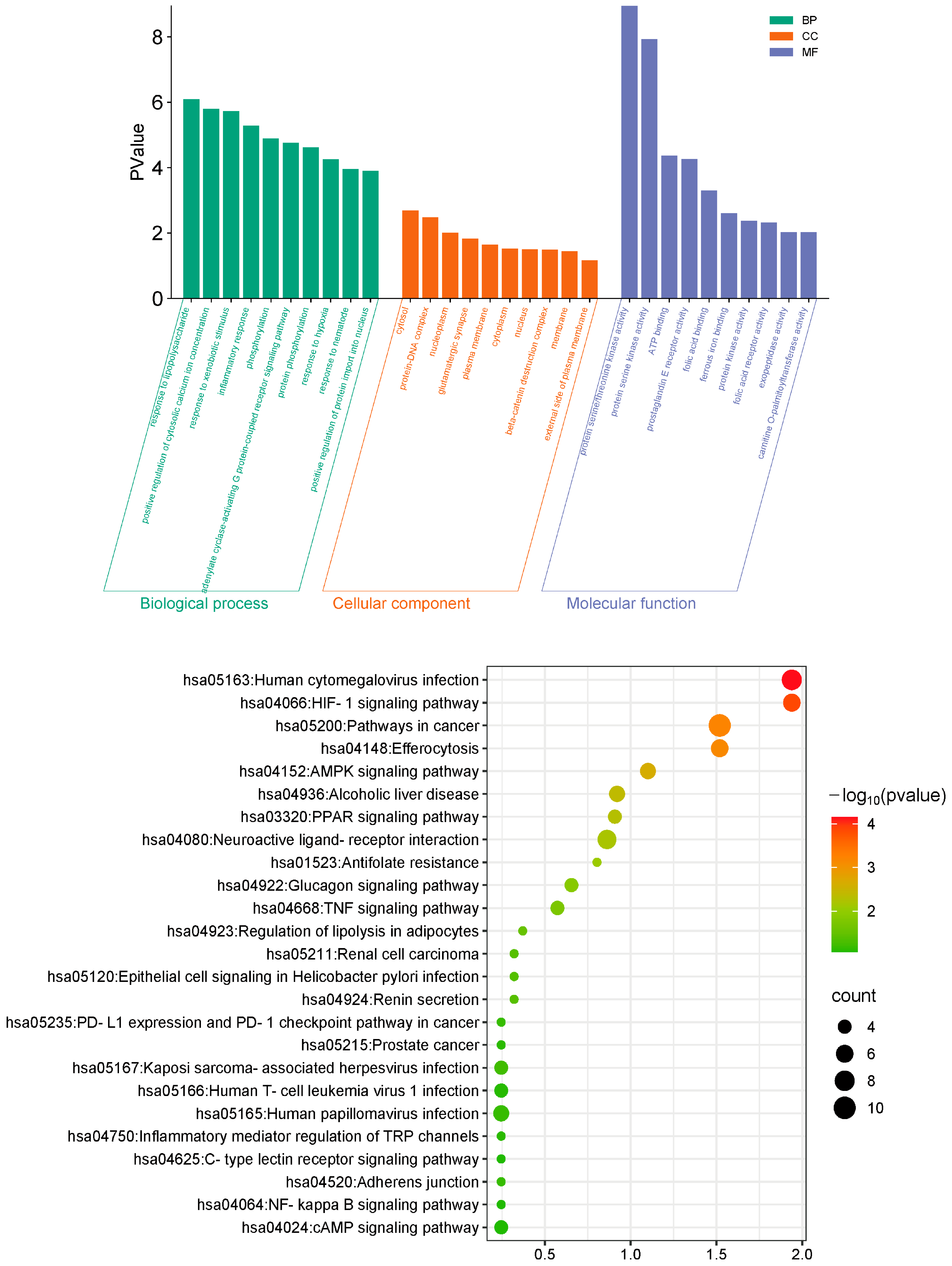

2.4. Functional Analysis of Common Targets of Roxadustat in PF Treatment

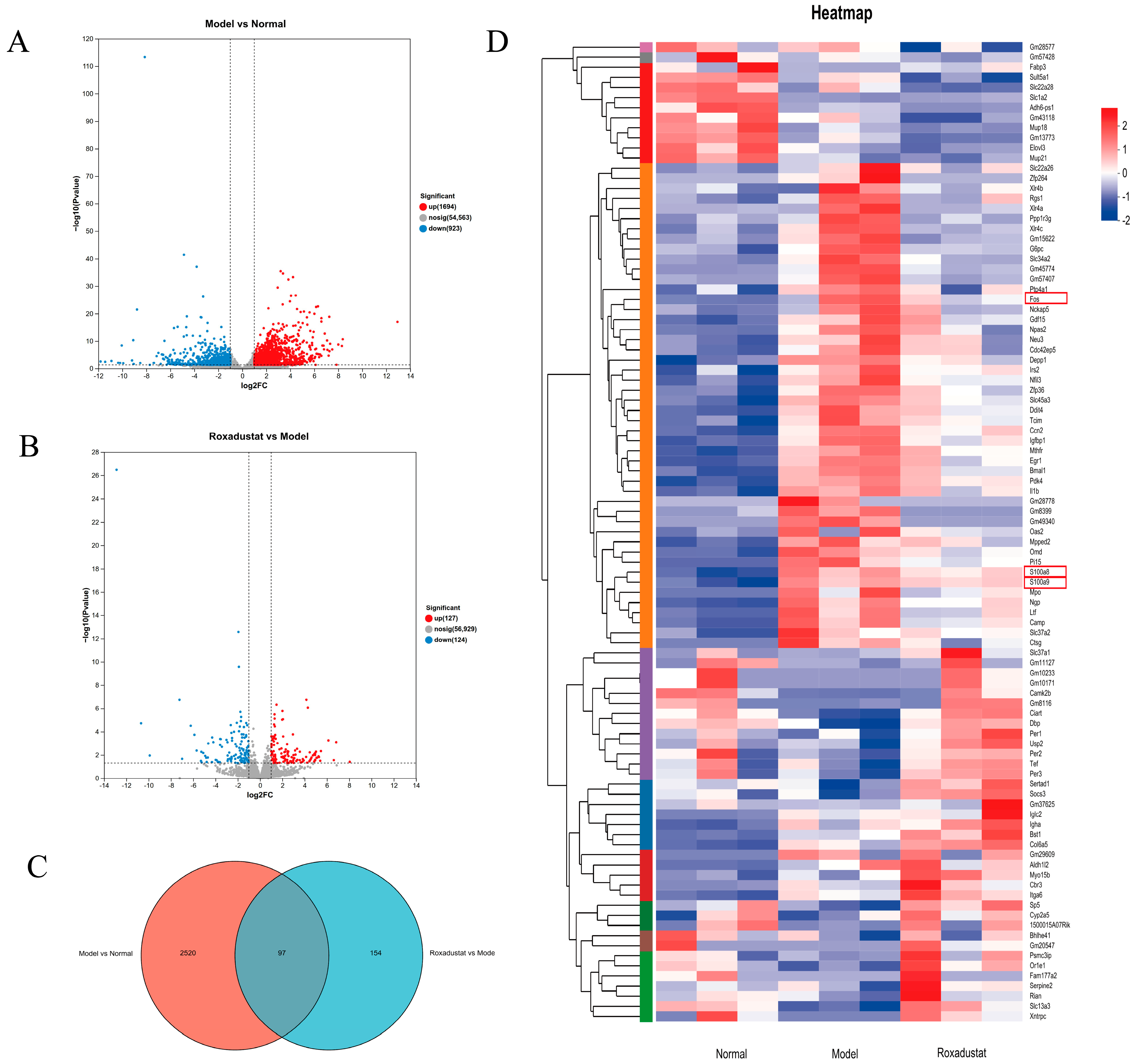

2.5. RNA-Seq Profiling and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

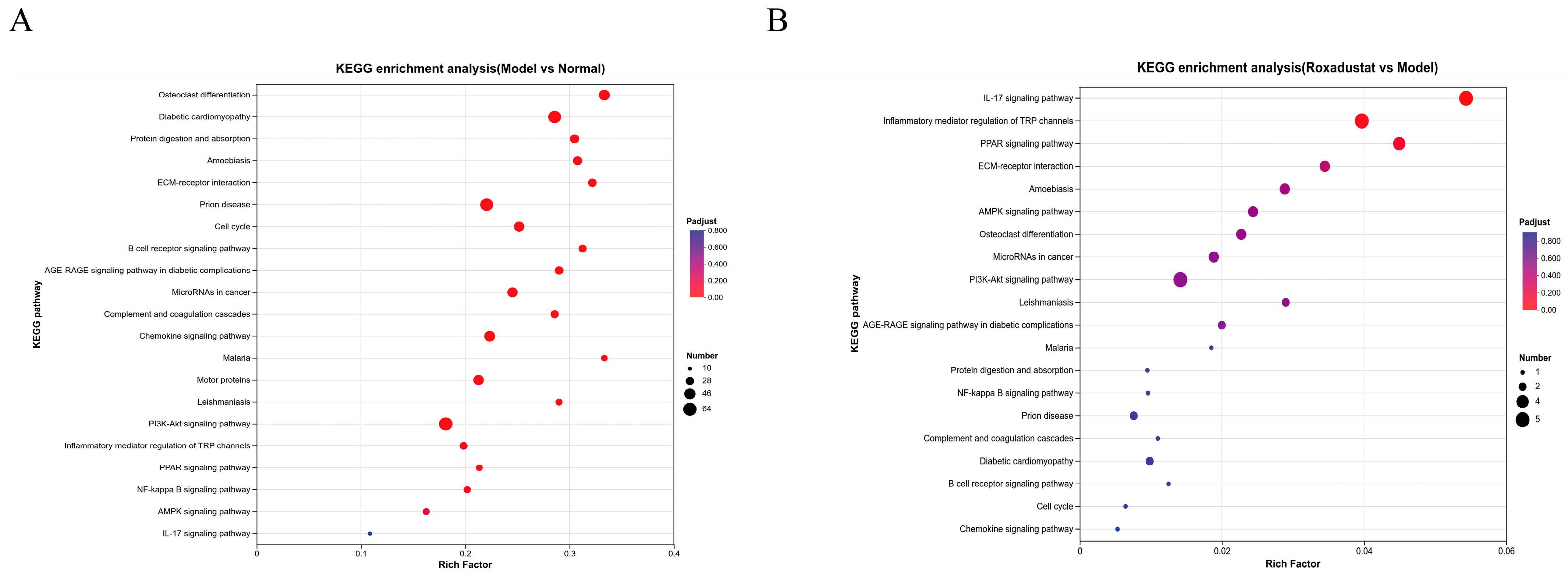

2.6. KEGG Analysis

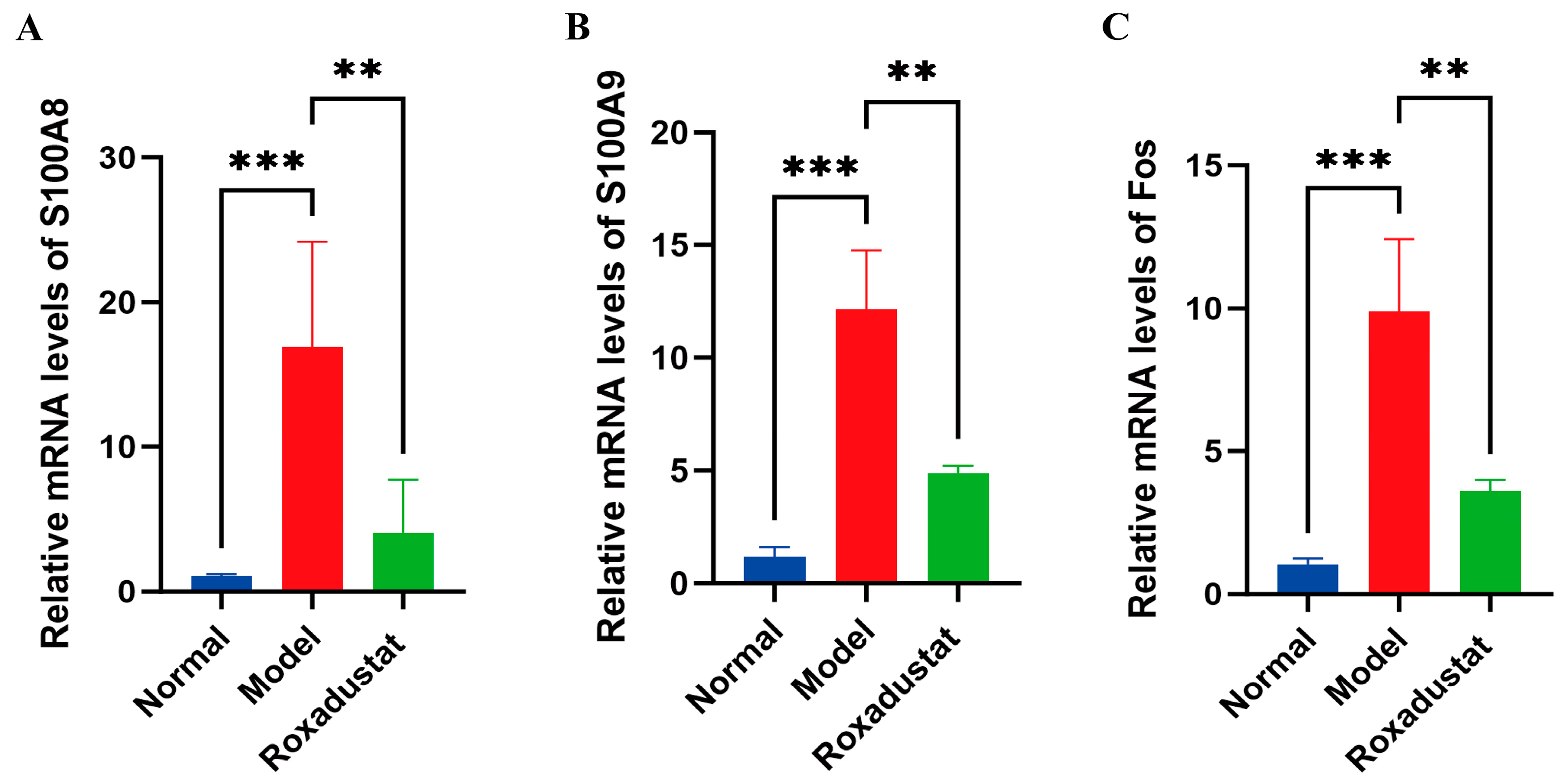

2.7. Validation of Gene Expression Profiles

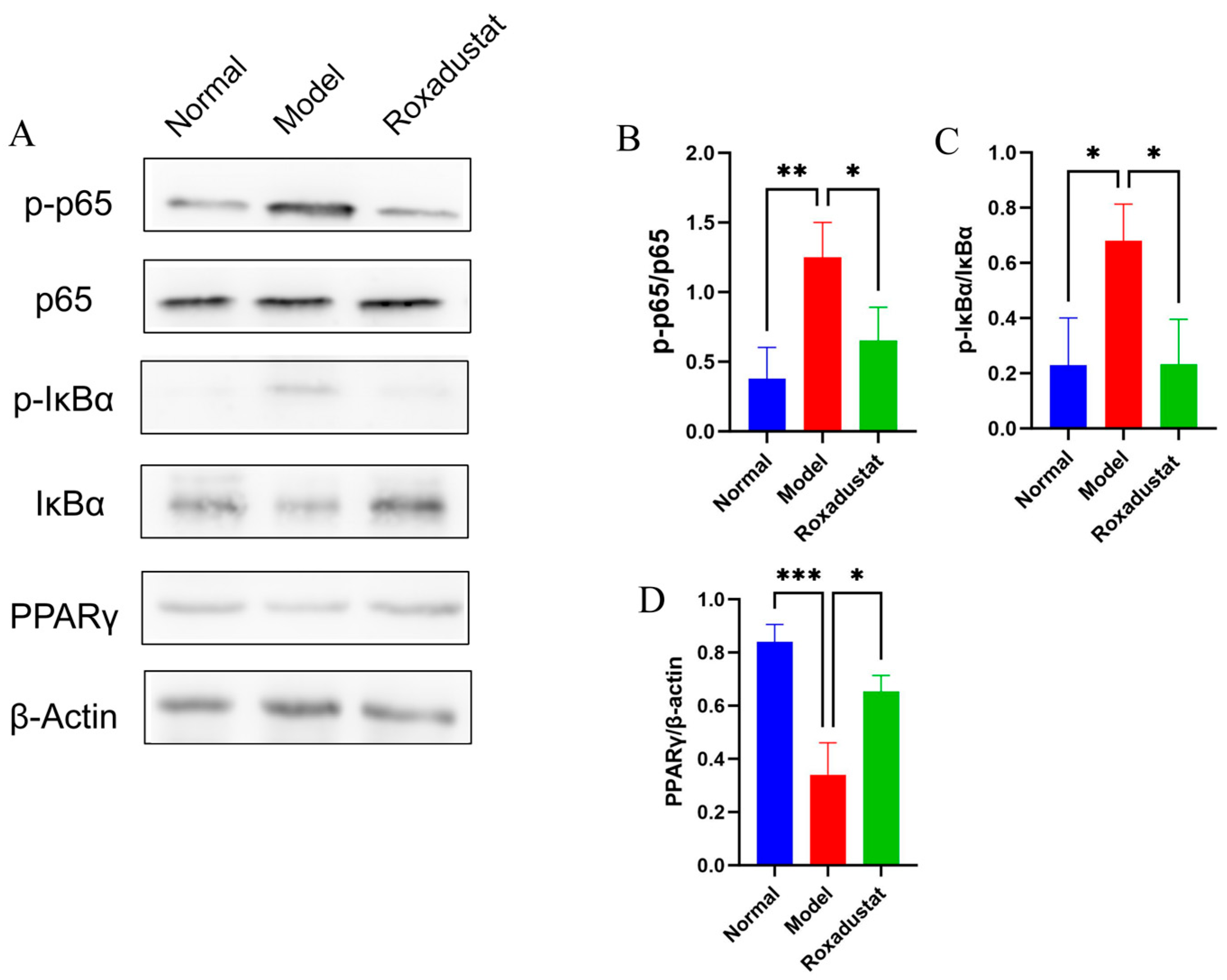

2.8. Roxadustat’s Impact on the NF-κB/PPARγ Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Experiment

4.2. Histopathology

4.3. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

4.4. Network Pharmacology

4.4.1. Compilation of Potential Roxadustat Targets

4.4.2. Collection of Gene Targets for PF

4.4.3. Identify Potential Therapeutic Targets

4.4.4. Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis of Shared Molecular Targets and PPI Networks

4.4.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Analysis of Transcriptomes

4.5.1. Sequencing and Separation of RNA

4.5.2. Gene Expression Variation Analysis and Biological Function Enrichment

4.6. Real-Time Reverse Transcription–Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analyses

4.7. Western Blot Analyses

4.8. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Fos | Fos Proto-Oncogene |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| PF | Pulmonary fibrosis |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium-binding protein A8 |

| S100A9 | S100 calcium-binding protein A9 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor-β1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

References

- Zhang, Y.S.; Tu, B.; Song, K.; Lin, L.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Lu, D.; Chen, Q.; Tao, H. Epigenetic hallmarks in pulmonary fibrosis: New advances and perspectives. Cell Signal. 2023, 110, 110842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassberg, M.K. Overview of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, evidence-based guidelines, and recent developments in the treatment landscape. Am. J. Manag. Care 2019, 25, S195–S203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kou, M.; Jiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, B.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wei, W. Real-world safety and effectiveness of pirfenidone and nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 80, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Gong, H.; Wei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, F. Hesperidin inhibits lung fibroblast senescence via IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway to suppress pulmonary fibrosis. Phytomedicine 2023, 112, 154680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeszczak, W.; Szczyra, D.; Śnit, M. Whether Prolyl Hydroxylase Blocker-Roxadustat-In the Treatment of Anemia in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Is the Future? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Fan, J.; Yang, T.; Shen, J.; Wang, L.; Ge, W. Investigating the therapeutic effects and mechanisms of Roxadustat on peritoneal fibrosis Based on the TGF-β/Smad pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 693, 149387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.G.; Gao, Y.Y.; Yin, Z.Q.; Wang, X.R.; Meng, X.S.; Zou, T.F.; Duan, Y.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Liao, C.Z.; Xie, Z.L.; et al. Roxadustat alleviates nitroglycerin-induced migraine in mice by regulating HIF-1α/NF-κB/inflammation pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, G.; Liu, F. HIF-α activation by the prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat suppresses chemoresistant glioblastoma growth by inducing ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Wang, K.; Meng, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhou, T.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. Roxadustat promotes hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/vascular endothelial growth factor signalling to enhance random skin flap survival in rats. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 3586–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, W. Roxadustat attenuates experimental pulmonary fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 331, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.P.; Baldi, A.; Kumar, N.; Pradhan, J. Harnessing network pharmacology in drug discovery: An integrated approach. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 4689–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, S. Integration of transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and systems pharmacology data to reveal the therapeutic mechanism underlying Chinese herbal Bufei Yishen formula for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 5247–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Fu, M.; Wang, M.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting TGF-β signal transduction for fibrosis and cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigdelioglu, R.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Meliton, A.Y.; O’Leary, E.; Witt, L.J.; Cho, T.; Sun, K.; Bonham, C.; Wu, D.; Woods, P.S.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β Promotes de Novo Serine Synthesis for Collagen Production. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 27239–27251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, B.; Azuelos, I.; Anastasiou, D.; Chambers, R.C. Fibrometabolism-An emerging therapeutic frontier in pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Signal 2021, 14, eaay1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Integrating mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoni, P.; Barisione, E.; Grosso, M.; Bertolotto, M.; Altieri, P.; Carbone, F.; Montecucco, F.; de Totero, D. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Derived Fibroblasts From Interstitial Lung Disease Patients: A Chance to Exploit 2D/3D Model of Pulmonary Fibrosis In Vitro. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2025, 30, 38726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.B.; Lawson, W.E.; Oury, T.D.; Sisson, T.H.; Raghavendran, K.; Hogaboam, C.M. Animal models of fibrotic lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratis, M.A.; Aidinis, V. Modeling pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2011, 17, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, A.L.; Lawson, W.E. Progress toward improving animal models for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 341, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, W.E.; Polosukhin, V.V.; Stathopoulos, G.T.; Zoia, O.; Han, W.; Lane, K.B.; Li, B.; Donnelly, E.F.; Holburn, G.E.; Lewis, K.G.; et al. Increased and prolonged pulmonary fibrosis in surfactant protein C-deficient mice following intratracheal bleomycin. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.B.; Hogaboam, C.M. Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2008, 294, L152–L160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, I.Y.; Bowden, D.H. The pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 1974, 77, 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Sheng, P.; Ma, B.; Xue, B.; Shen, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Hou, J.; Ren, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Elucidation of the mechanism of Yiqi Tongluo Granule against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury based on a combined strategy of network pharmacology, multi-omics and molecular biology. Phytomedicine 2023, 118, 154934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austermann, J.; Roth, J.; Barczyk-Kahlert, K. The Good and the Bad: Monocytes’ and Macrophages’ Diverse Functions in Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.B.; Cowley, C.J.; Sajjath, S.M.; Barrows, D.; Yang, Y.; Carroll, T.S.; Fuchs, E. Establishment, maintenance, and recall of inflammatory memory. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1758–1774.e1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyette, J.; Geczy, C.L. Inflammation-associated S100 proteins: New mechanisms that regulate function. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 821–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruenster, M.; Immler, R.; Roth, J.; Kuchler, T.; Bromberger, T.; Napoli, M.; Nussbaumer, K.; Rohwedder, I.; Wackerbarth, L.M.; Piantoni, C.; et al. E-selectin-mediated rapid NLRP3 inflammasome activation regulates S100A8/S100A9 release from neutrophils via transient gasdermin D pore formation. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Yeh, L.K.; Hung, K.H.; Chiu, Y.J.; Hsieh, C.H.; Ma, C.P. Machine Learning-Driven Transcriptome Analysis of Keratoconus for Predictive Biomarker Identification. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramasivam, S.; Murugesan, J.; Vedagiri, H.; Perumal, S.S.; Ekambaram, S.P. Virtual Probing on the Influence of Ca2+ and Zn2+ Bound S100A8 and S100A9 Proteins Towards their Interaction Against Pattern Recognition Receptors Aggravating Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 83, 1919–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruenster, M.; Vogl, T.; Roth, J.; Sperandio, M. S100A8/A9: From basic science to clinical application. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 167, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, R.; Bhatt, H.N.; Beaven, E.; Nurunnabi, M. Emerging delivery approaches for targeted pulmonary fibrosis treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 204, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Xiao, Y.; He, J.; Ren, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, C.; Shu, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. Euchrenone A10 attenuates septic lung injury though S100A8/A9-dependent TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.; Tian, Z.; Gao, P.; Xiao, H.; Qi, X.; Yu, Y.; Ding, X.; Yang, L.; Zong, L. HBsAg/β2GPI activates the NF-κB pathway via the TLR4/MyD88/IκBα axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, B.; Lin, C.; Gong, Z.; An, X. TREM2 inhibits inflammatory responses in mouse microglia by suppressing the PI3K/NF-κB signaling. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xuan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, L.; Guan, H.; Yang, S.; He, J.; Shi, D.; Wang, Y. Netrin-1 alleviates subarachnoid haemorrhage-induced brain injury via the PPARγ/NF-KB signalling pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2256–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, C.; Hoque, M.T.; Bendayan, R. PPAR agonists for the treatment of neuroinflammatory diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Q.; Costa, M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Sun, B.J.; Yu, L.M.; Chen, Q.Q.; Han, X.X.; Liu, Y.H. HIF-1α activator DMOG inhibits alveolar bone resorption in murine periodontitis by regulating macrophage polarization. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 107901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.D.; Smith, T.M.; Stewart, L.V.; Sakwe, A.M. Hypoxia-Inducible Expression of Annexin A6 Enhances the Resistance of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to EGFR and AR Antagonists. Cells 2022, 11, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kuai, Q.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Zhou, H.; Han, G.; Jiang, X.; Ren, S.; Yu, Q. Overexpression of TIM-3 in Macrophages Aggravates Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, H.; Fang, M.; Hang, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Chen, M. Pirfenidone modulates macrophage polarization and ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 8662–8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C. Cell tracing reveals the transdifferentiation fate of mouse lung epithelial cells during pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, A.; Yang, F.; Xie, C.; Du, W.; Mohammadtursun, N.; Wang, B.; Le, J.; Dong, J. Pulmonary fibrosis model of mice induced by different administration methods of bleomycin. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wei, Q.; Song, K.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; Su, G.; Peng, L.; Fu, B.; et al. Tangeretin attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1247800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ouyang, S.; Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; Huang, K.; Gong, J.; Zheng, S.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, H. PharmMapper server: A web server for potential drug target identification using pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W609–W614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, N.; Zhou, P.; Liu, F.; Su, H.; Han, L.; Lu, C. Integrating network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental validation to reveal the mechanism of Radix Rehmanniae in psoriasis. Medicine 2024, 103, e40211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Shen, X.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zeng, J.; Lin, J.; Yue, L.; Lai, J.; Li, Y.; et al. TMEA, a Polyphenol in Sanguisorba officinalis, Promotes Thrombocytopoiesis by Upregulating PI3K/Akt Signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 708331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequences | GenBankTM Accession No. |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | Forward AGGCATTGCTGACAGGATG | NM_133360 |

| Reverse TGCTGATCCACATCTGCTGG | ||

| TNF-α | Forward GAGAAGAGGCTGAGACATAG | NM_001278601.1 |

| Reverse GTGGAACTGGCAGAAGAG | ||

| IL-1β | Forward TTCTCCACAGCCACAATG | NM_008361.4 |

| Reverse CAGCAGCACATCAACAAG | ||

| TGF-β1 | Forward CTGTATTCCGTCTCCTTGG | NM_011577.2 |

| Reverse ATTCCTGGCGTTACCTTG | ||

| S100A8 | Forward TACTCCTTGTGGCTGTCT | NM_013650.2 |

| Reverse TTCCTTGCGATGGTGATAA | ||

| S100A9 | Forward TGTCCTTCCTTCCTAGAGTAT | NM_001281852.1 |

| Reverse GCAGCATAACCACCATCA | ||

| Fos | Forward GCAACGCAGACTTCTCAT | NM_010234.3 |

| Reverse GCTGACAGATACACTCCAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Ye, H.; Tang, H.; Huang, M.; Jia, S.; Shao, J.; Wu, J.; Yao, X. Mechanistic Evaluation of Roxadustat for Pulmonary Fibrosis: Integrating Network Pharmacology, Transcriptomics, and Experimental Validation. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010179

Zhang C, Huang X, Ye H, Tang H, Huang M, Jia S, Shao J, Wu J, Yao X. Mechanistic Evaluation of Roxadustat for Pulmonary Fibrosis: Integrating Network Pharmacology, Transcriptomics, and Experimental Validation. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010179

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Congcong, Xinyue Huang, Huina Ye, Haidong Tang, Minwei Huang, Shu Jia, Jingping Shao, Jingyi Wu, and Xiaomin Yao. 2026. "Mechanistic Evaluation of Roxadustat for Pulmonary Fibrosis: Integrating Network Pharmacology, Transcriptomics, and Experimental Validation" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010179

APA StyleZhang, C., Huang, X., Ye, H., Tang, H., Huang, M., Jia, S., Shao, J., Wu, J., & Yao, X. (2026). Mechanistic Evaluation of Roxadustat for Pulmonary Fibrosis: Integrating Network Pharmacology, Transcriptomics, and Experimental Validation. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010179