Protection by Vitis vinifera L. Against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Ferroptosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

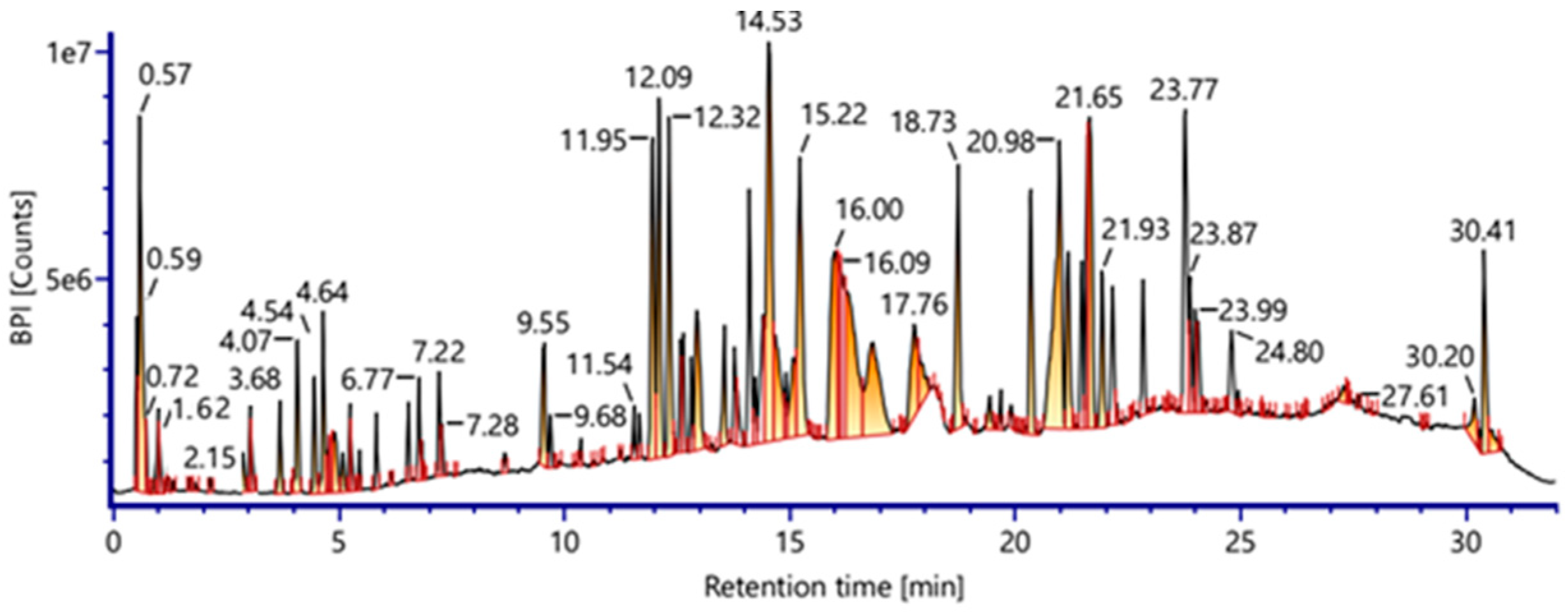

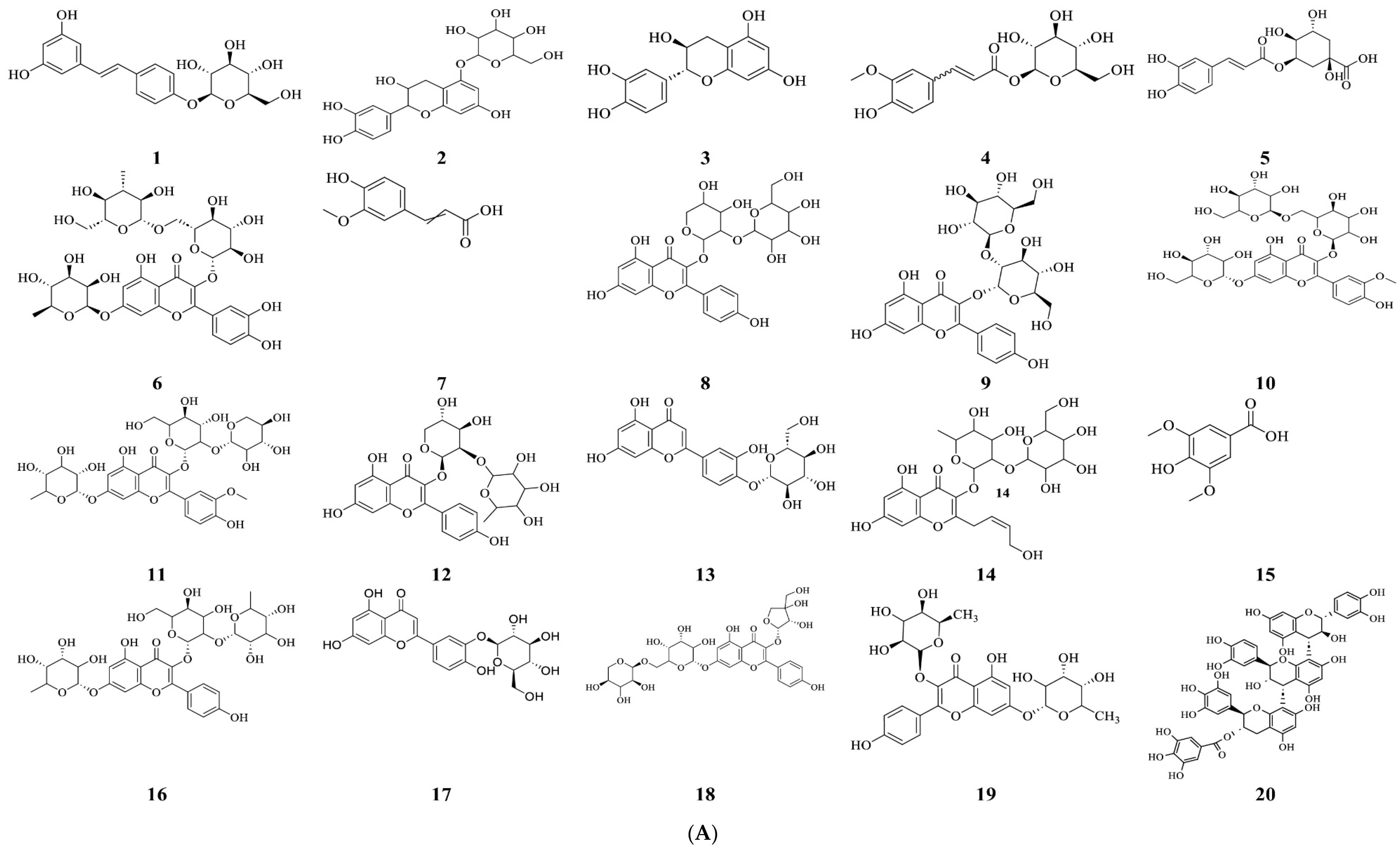

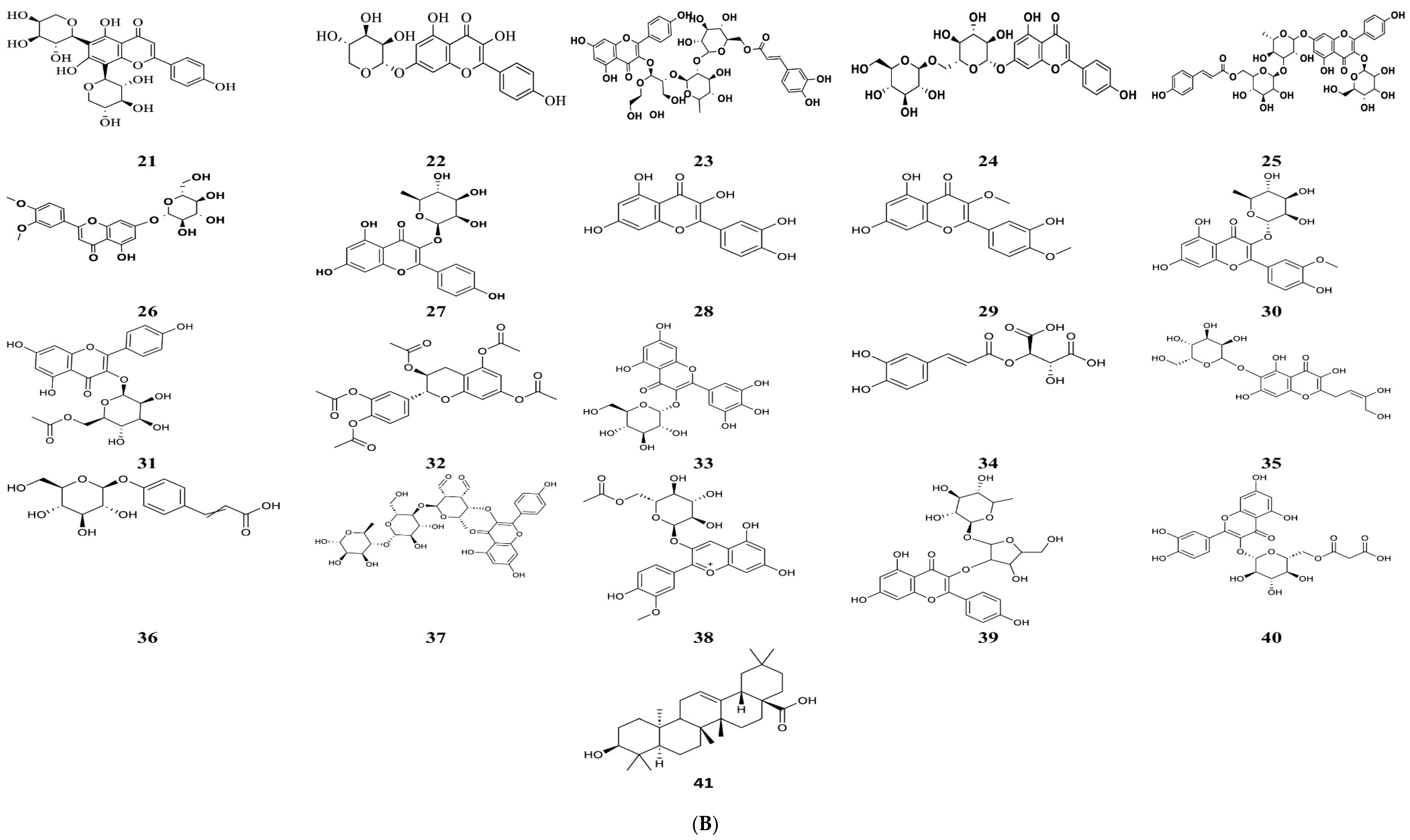

2.1. Phytochemical Characterization of Vitis vinifera Seed Extract

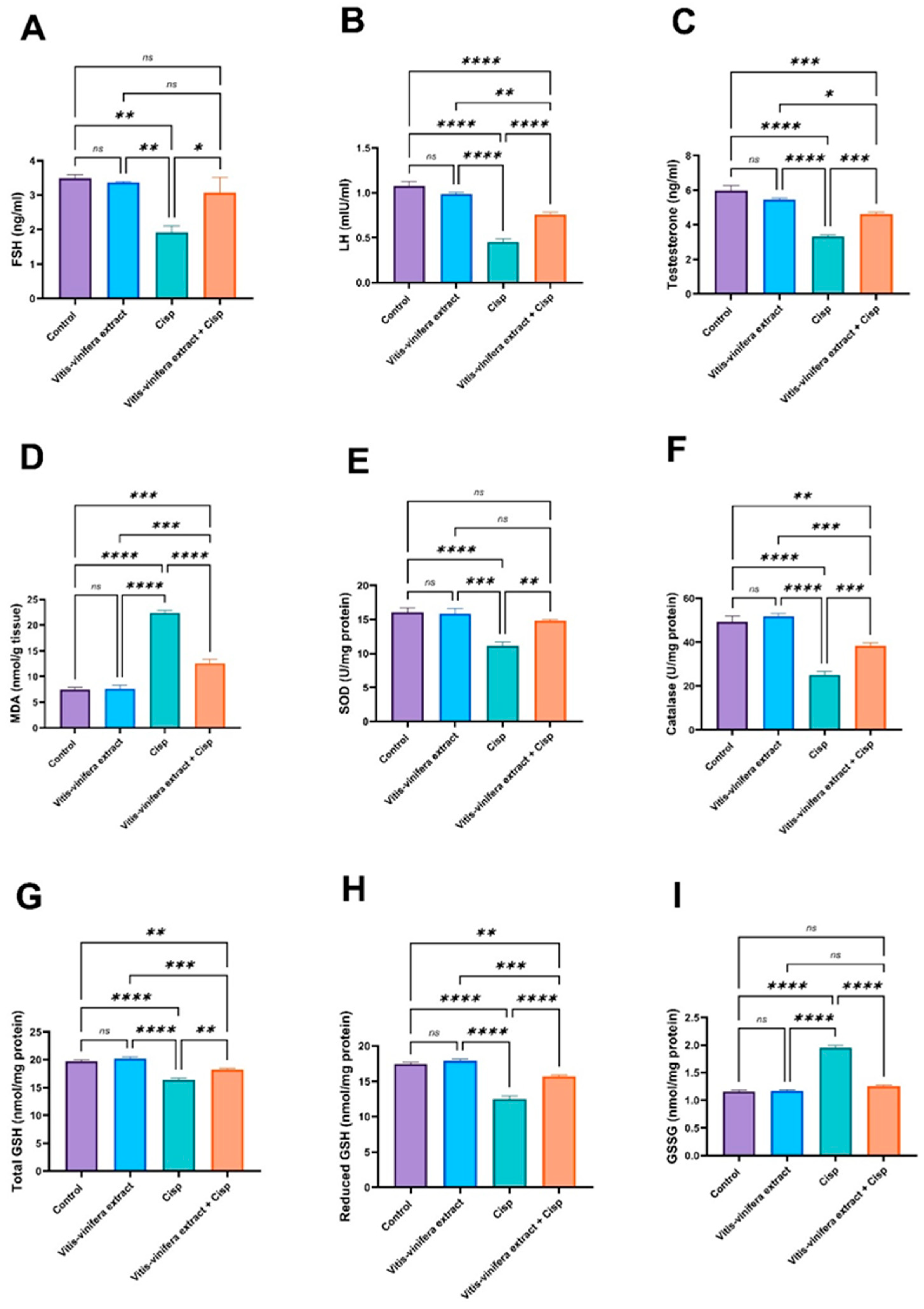

2.2. The Effect of Vitis vinifera Extract on Blood FSH, LH, and Testosterone Levels in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats

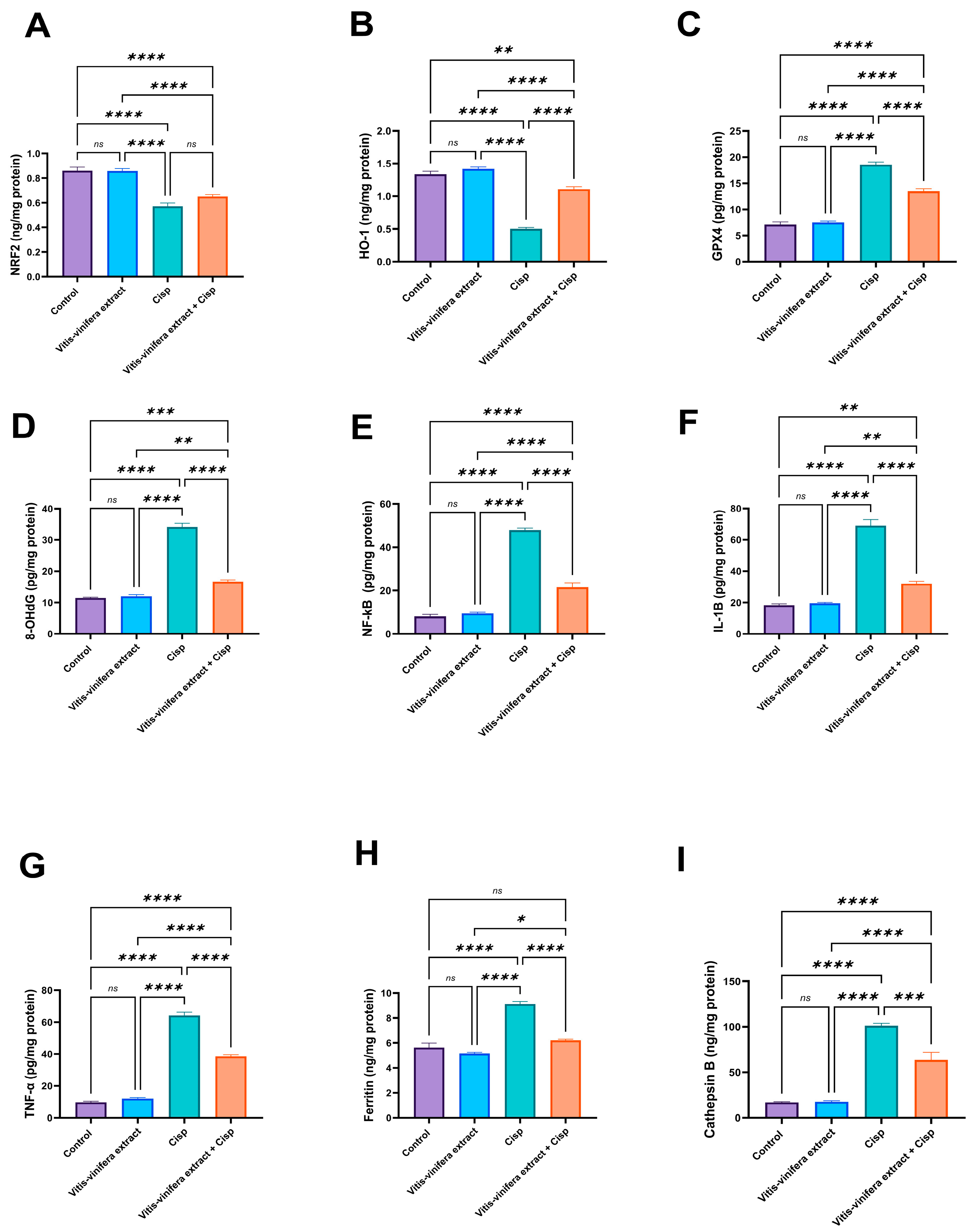

2.3. Effect of Vitis vinifera Extract on the Testicular Oxidative/Anti-Oxidative Biomarkers (MDA, SOD, CAT, Total GSH, Reduced GSH, GSSG, NRF2, Ho-1, Gpx4, and 8-OHDG) in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats

2.4. Effect of Vitis vinifera Extract on Testicular Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines as NFκB IL-1β, TNF-α and Some Ferroptosis Factors, in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats

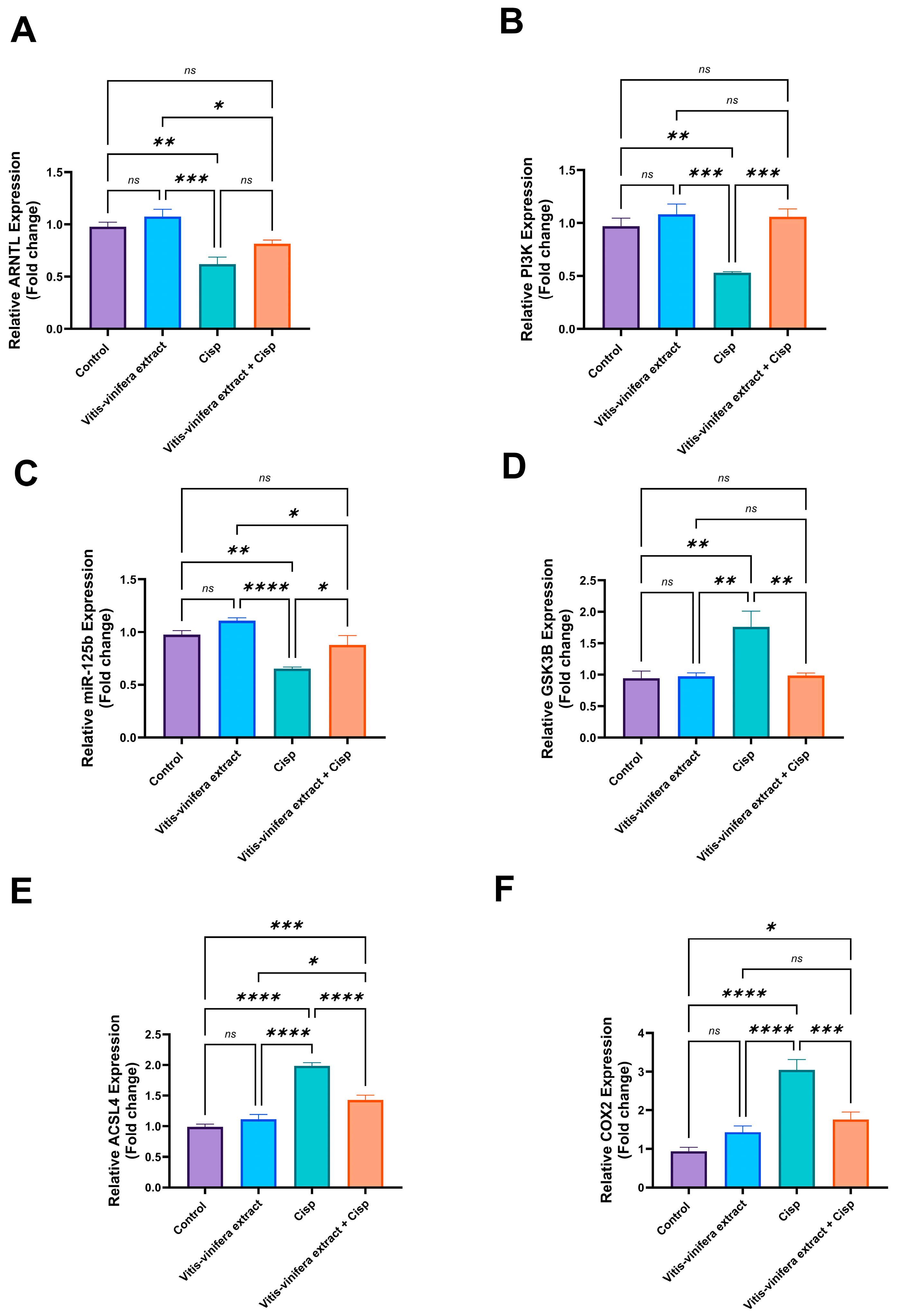

2.5. Effect of Vitis vinifera Extract on Gene Expression of ARNTL, ASCL4, PI3K, GSK3B, COX2, and miRNA 125-b in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Damage in Rats

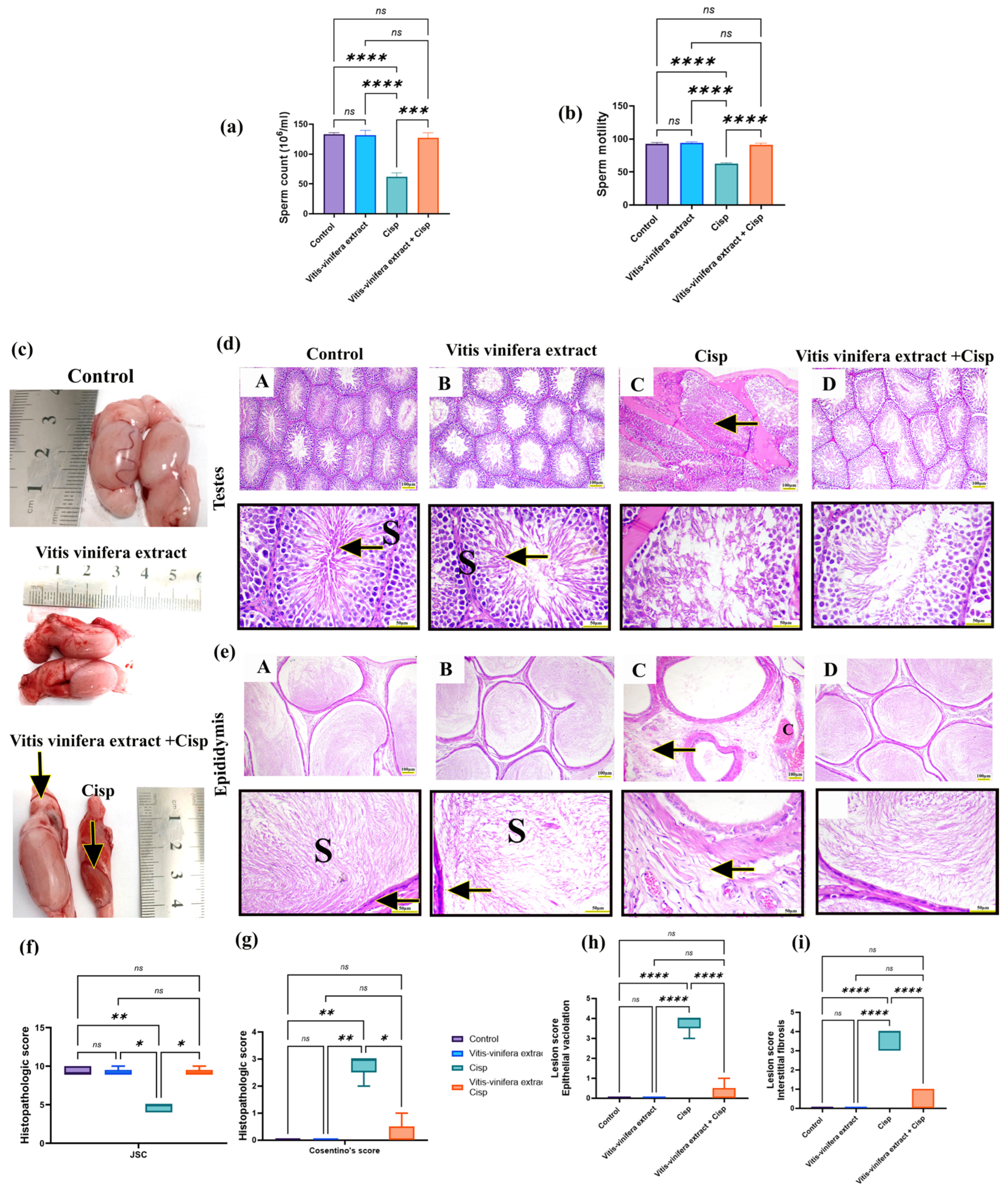

2.6. Effect of Vitis vinifera L. Extract on Sperm Count and Motility in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury in Rats

2.7. Effect of Vitis vinifera L. Extract on Testicular and Epididymal Histoarchitecture in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury in Rats

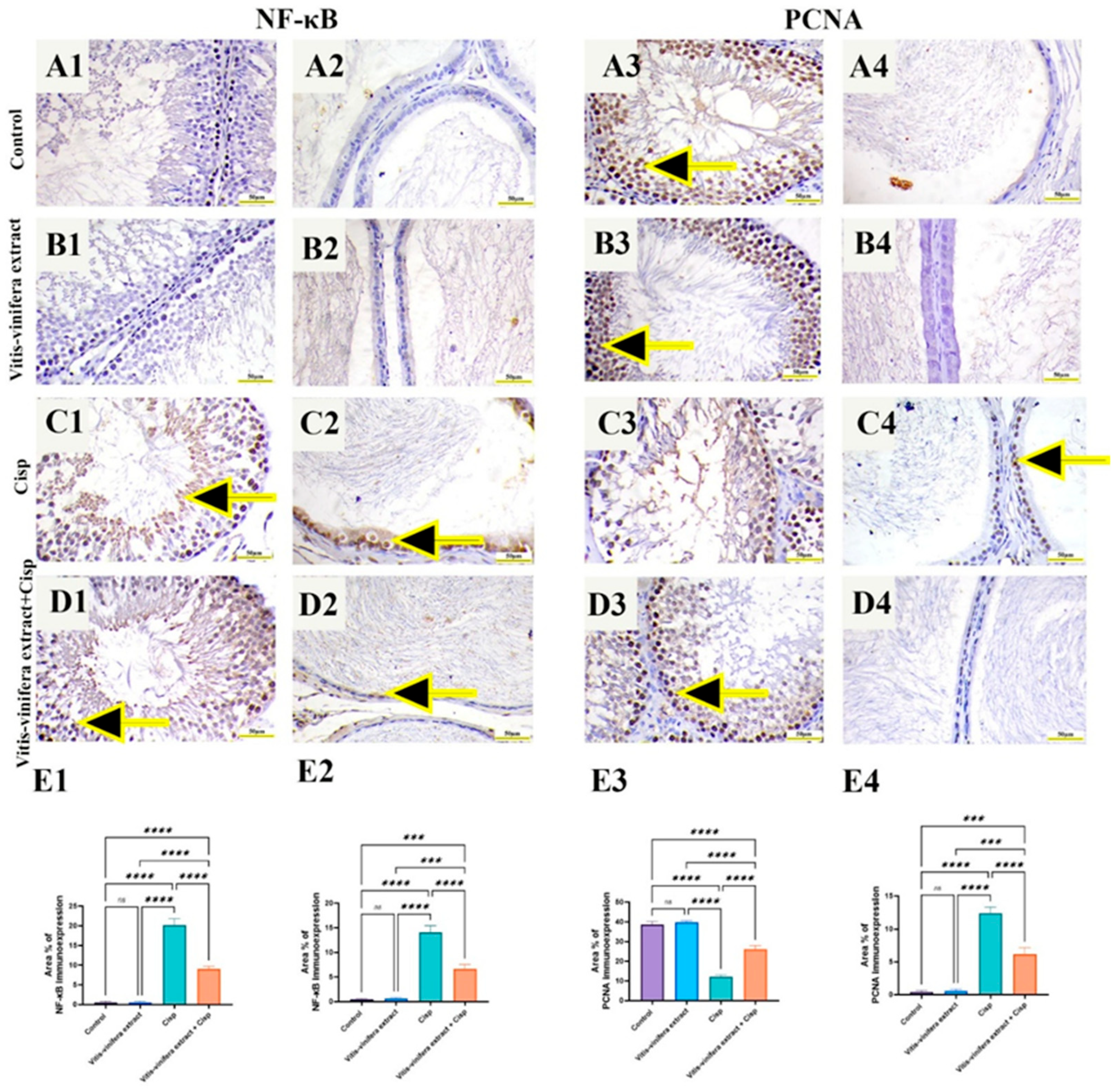

2.8. Effect of Vitis vinifera L. Extract on NF-kB p65 and PCNA Immune-Expression in Cisplatin-Induced Testicular and Epididymal Damage in Rats

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Chemicals

4.2. Plant Materials

4.3. Preparation of Crude Vitis vinifera L. Seeds Extract

4.4. QTOF-HRMS/MS

4.5. Experimental Animals

4.6. Experimental Design

4.7. Blood and Tissue Collection

4.8. Sperm Parameters Measurements

4.9. Sperm Counting

4.10. Sperm Motility

4.11. Serum FSH, LH, and Testosterone Measurement

4.12. Testicular Oxidative and Antioxidant Biomarkers Evaluation

4.13. Testicular Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Some Ferroptosis Biomarkers Assessments

4.14. Gene Expression Analysis Using Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

4.15. Relative Quantification of the Expression of miR-155 Using PCR

4.16. Histopathologic Examination

4.17. Immunohistochemical Protein Assay

4.18. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilbert, K.; Nangia, A.K.; Dupree, J.M.; Smith, J.F.; Mehta, A. Fertility preservation for men with testicular cancer: Is sperm cryopreservation cost effective in the era of assisted reproductive technology? Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 92.e91–92.e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, S. Fertility preservation in male patients with cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 55, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famurewa, A.C.; Ekeleme-Egedigwe, C.A.; Onwe, C.S.; Egedigwe, U.O.; Okoro, C.O.; Egedigwe, U.J.; Asogwa, N.T. Ginger juice prevents cisplatin-induced oxidative stress, endocrine imbalance and NO/iNOS/NF-κB signalling via modulating testicular redox-inflammatory mechanism in rats. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakalopoulos, I.; Dimou, P.; Anagnostou, I.; Zeginiadou, T. Impact of cancer and cancer treatment on male fertility. Hormones 2015, 14, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami Jourabi, F.; Yari, S.; Amiri, P.; Heidarianpour, A.; Hashemi, H. The ameliorative effects of methylene blue on testicular damage induced by cisplatin in rats. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbarz, N.; Shafiei Seifabadi, Z.; Moaiedi, M.Z.; Mansouri, E. Assessment of the effect of sodium hydrogen sulfide (hydrogen sulfide donor) on cisplatin-induced testicular toxicity in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8119–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-E.; Lai, Y.-H.; Yang, K.-C.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, C.-L.; Tsai, P.-S. Counteracting cisplatin-induced testicular damages by natural polyphenol constituent honokiol. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.A.; Qutub, H.O.; Fouad, A.E.A.; Audeh, A.M.; Al-Melhim, W.N. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate counters cisplatin toxicity of rat testes. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeba, G.H.; Hamza, A.A.; Hassanin, S.O. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 with hemin alleviates cisplatin-induced reproductive toxicity in male rats and enhances its cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cell line. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 264, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iman, M.; Araghi, M.; Heidari, T.; Mohammadi, V. Melissa officinalis and vitamin E as the potential therapeutic candidates for reproductive toxicity caused by anti-cancer drug, cisplatin, in male rats. Recent Pat. Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2017, 12, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.H.; Abdelkader, N.F.; Abd El-Raouf, O.M.; Fawzy, H.M.; El-Denshary, E.-E.-D.S. Carvedilol alleviates testicular and spermatological damage induced by cisplatin in rats via modulation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2016, 39, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famurewa, A.C.; Prabhune, N.M.; Prabhu, S. Natural product mitigation of ferroptosis in platinum-based chemotherapy toxicity: Targeting the underpinning oxidative signaling pathways. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2025, 77, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R.; Mathai, M.L.; Zulli, A. Cisplatin for cancer therapy and overcoming chemoresistance. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro Fernandes, C.; Santana, L.F.; Dos Santos, J.R.; Fernandes, D.S.; Hiane, P.A.; Pott, A.; Freitas, K.d.C.; Bogo, D.; do Nascimento, V.A.; Filiú, W.F.d.O.; et al. Nutraceutical potential of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seed oil in oxidative stress, inflammation, obesity and metabolic alterations. Molecules 2023, 28, 7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ashmawy, I.M.; Saleh, A.; Salama, O.M. Effects of marjoram volatile oil and grape seed extract on ethanol toxicity in male rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 101, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chedea, V.S.; Braicu, C.; Socaciu, C. Antioxidant/prooxidant activity of a polyphenolic grape seed extract. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Liu, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Hou, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Chang, X.; Sun, Y. Grape seed procyanidins extract attenuates Cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and testosterone synthase inhibition in rat testes. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2018, 64, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tarras, A.E.-S.; Attia, H.F.; Soliman, M.M.; El Awady, M.A.; Amin, A.A. Neuroprotective effect of grape seed extract against cadmium toxicity in male albino rats. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.M.; Elekhnawy, E.; Shaldam, M.A.; Alqahtani, M.J.; Altwaijry, N.; Attallah, N.G.M.; Hussein, I.A.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Negm, W.A.; Salem, E.A. Rosuvastatin and diosmetin inhibited the HSP70/TLR4/NF-κB p65/NLRP3 signaling pathways and switched macrophage to M2 phenotype in a rat model of acute kidney injury induced by cisplatin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaberi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Grapes (Vitis vinifera) as a potential candidate for the therapy of the metabolic syndrome. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-G.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Wu, Y.-J.; Tian, X. Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism of proanthocyanidins from grape seeds. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2001, 22, 1117–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, T.; Schieber, A.; Kammerer, D.R.; Carle, R. Residues of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seed oil production as a valuable source of phenolic antioxidants. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Tan, X.; Yang, D.; Lv, Z.; Jiang, H.; Lu, J.; Baiyun, R.; Zhang, Z. GSPE reduces lead-induced oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2 pathway and suppressing miR153 and GSK-3β in rat kidney. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 42226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Dai, X.; Ma, X.; Bao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extracts prevent high glucose-induced endothelia dysfunction via PKC and NF-κB inhibition. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 79, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.A.; Edrees, G.M.; El-Gamel, E.M.; El-Sayed, E.A. Proanthocyanidin and fish oil potent activity against cisplatin-induced renal cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in rats. Ren. Fail. 2015, 37, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitters, B.; Masquelier, J. OPC in Practice: Biflavanals and Their Application; Alfa Omega: Rome, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carini, M.; Aldini, G.; Bombardelli, E.; Morazzoni, P.; Morelli, R. Free radicals scavenging action and anti-enzyme activities of procyanidines from Vitis vinifera. A mechanism for their capillary protective action. Arzneimittel-Forschung 1994, 44, 592–601. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Yu, J.; Pohorly, J.E.; Kakuda, Y. Polyphenolics in grape seeds—Biochemistry and functionality. J. Med. Food 2003, 6, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozak Yıldız, H.; Kalkan, K.T.; Baydilli, N.; Gönen, Z.B.; Cengiz Mat, Ö.; Köseoğlu, E.; Önder, G.Ö.; Yay, A. Extracellular vesicles therapy alleviates cisplatin-ınduced testicular tissue toxicity in a rat model. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, K.K.; Kim, H.K.; Choi, B.R.; Karna, K.K.; You, J.H.; Cha, J.S.; Shin, Y.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, J.K. Dose-dependent effects of cisplatin on the severity of testicular injury in Sprague Dawley rats: Reactive oxygen species and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 3959–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahab, D.K.; Ibrahim, W.W.; Abd El-Aal, R.A.; Abdel-Latif, H.A.; Abdelkader, N.F. Grape seed extract improved the fertility-enhancing effect of atorvastatin in high-fat diet-induced testicular injury in rats: Involvement of antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.G.; Zoheir, M.A.; Hashem, F.E.Z.A.; Zewail, M.; Abd-el-Moneim, R.A. Histological and Biochemical Evaluation of the Possible Protective Effect of Thymoquinone Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers Versus Thymoquinone on Cisplatin Induced Testicular Toxicity in Adult Rats. Egypt. J. Histol. 2023, 46, 1911–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, Y.; Badr, A.M.; Aloyouni, S.; Alkahtani, M.M.; Sarawi, W.S.; Ali, R.; Alsultan, D.; Almufadhili, S.; Almasud, D.H.; Hasan, I.H. Morin hydrate protects against cisplatin-induced testicular toxicity by modulating ferroptosis and steroidogenesis genes’ expression and upregulating Nrf2/Heme oxygenase-1. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heibashy, D.M.; Morsy, W.A. Effectiveness of hesperidin and rutin on cisplatin-induced testicular dysfunction in rats. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2025, 86, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, M.; Sawires, S. Possible Ameliorating Role of Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Extract on Seminiferous Tubules Toxicity Induced by Aluminium Oxide Nanoparticles in Adult Rats: Histological and Biochemical Study. Egypt. J. Histol. 2023, 46, 1512–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Gao, L.; Rudebush, T.L.; Yu, L.; Zucker, I.H. Extracellular vesicles regulate sympatho-excitation by Nrf2 in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.A.; Demir, S.; Mungan, S.A.; Alemdar, N.T.; Menteşe, A.; Aliyazıcıoǧlu, Y. Chlorogenic acid protects against cisplatin-induced testicular damage: A biochemical and histological study. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2025, 76, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.-g. Reactive oxygen species in TNFα-induced signaling and cell death. Mol. Cells 2010, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Maes, M. Role of the Toll Like receptor (TLR) radical cycle in chronic inflammation: Possible treatments targeting the TLR4 pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, C.; Mei, G.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, Y.; Gao, C.; Yao, P. Quercetin alleviates ferroptosis of pancreatic β cells in type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, H.; Shen, W.; Zha, X.; Gao, M.; Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, Q. Proanthocyanidin promotes functional recovery of spinal cord injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2020, 107, 101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Xin, P.; Zhao, L.; Kong, C.; Piao, C.; Wu, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z. Ferroptosis is crucial for cisplatin induced sertoli cell injury via n6-methyladenosine dependent manner. World J. Men’s Health 2024, 42, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Hamano, H.; Horinouchi, Y.; Miyamoto, L.; Hirayama, T.; Nagasawa, H.; Tamaki, T.; Tsuchiya, K. Role of ferroptosis in cisplatin-induced acute nephrotoxicity in mice. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 67, 126798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Zheng, Z.; Tang, D.; Lu, X.; He, Y. Inhibition of ferroptosis protects House Ear Institute-Organ of Corti 1 cells and cochlear hair cells from cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 12065–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.; Guru, D.; Pradhan, A.; Jena, S.R.; Goutami, L.; Nayak, J.; Sahu, A.; Samanta, L. Is Ferroptosis a cause for concern in Male Infertility. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025, 137, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Xia, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yuan, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, M.; Li, E. High concentration of iron ions contributes to ferroptosis-mediated testis injury. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.-W.; Du, Y.; Ma, S.-S.; Shi, Y.-C.; Xu, H.-C.; Deng, L.; Chen, X.-Y. Proanthocyanidins attenuates ferroptosis against influenza-induced acute lung injury in mice by reducing IFN-γ. Life Sci. 2023, 314, 121279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Hansen, A.; Ord, T.; Bebas, P.; Chappell, P.E.; Giebultowicz, J.M.; Williams, C.; Moss, S.; Sehgal, A. The circadian clock protein BMAL1 is necessary for fertility and proper testosterone production in mice. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2008, 23, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodžić, A.; Ristanović, M.; Zorn, B.; Tulić, C.; Maver, A.; Novaković, I.; Peterlin, B. Genetic variation in circadian rhythm genes CLOCK and ARNTL as risk factor for male infertility. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Zhu, B.; Shao, S.; Yuan, L. Grape seed procyanidin suppresses inflammation in cigarette smoke-exposed pulmonary arterial hypertension rats by the PPAR-γ/COX-2 pathway. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, R.M.; Cortés-Espinar, A.J.; Soliz-Rueda, J.R.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Casas, F.; Colom-Pellicer, M.; Aragonès, G.; Avila-Román, J.; Muguerza, B.; Mulero, M.; et al. Time-of-day circadian modulation of grape-seed procyanidin extract (GSPE) in hepatic mitochondrial dynamics in cafeteria-diet-induced obese rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Isagawa, T.; Oshima, M.; Iwama, A.; Shimba, S.; Okamura, H.; Manabe, I. Bmal1 regulates inflammatory responses in macrophages by modulating enhancer RNA transcription. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.; Mirizio, G.G.; Barin, G.R.; De Andrade, R.V.; Nimer, N.F.S.; La Sala, L. Clock genes, inflammation and the immune system—Implications for diabetes, obesity and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiey, S.I.; Ahmed, K.A.; Abo-Saif, A.A.; Abo-Youssef, A.M.; Mohamed, W.R. Galantamine mitigates testicular injury and disturbed spermatogenesis in adjuvant arthritic rats via modulating apoptosis, inflammatory signals, and IL-6/JAK/STAT3/SOCS3 signaling. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altyar, A.E.; Albadrani, G.M.; Farouk, S.M.; Alamoudi, M.K.; Sayed, A.A.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Al-Ghadi, M.Q.; Saleem, R.M.; Sakr, H.I.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects of sesamin against cisplatin-induced renal and testicular toxicity in rats. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2378212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, N.; Aoyagi, T.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, T. Amelioration of cisplatin nephrotoxicity by genetic or pharmacologic blockade of prostaglandin synthesis. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriu, T.; Bolfa, P.; Suciu, S.; Cimpean, A.; Daradics, Z.; Catoi, C.; Armencea, G.; Baciut, G.; Bran, S.; Dinu, C.; et al. Grape seed extract reduces the degree of atherosclerosis in ligature-induced periodontitis in rats–an experimental study. J. Med. Life 2020, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Gao, H.-Q.; Xu, L.; Li, B.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.-H. Cardioprotective effects of grape seed proanthocyanidins extracts in streptozocin induced diabetic rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2007, 50, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-H.; Tseng, P.-C.; Satria, R.D.; Lin, C.-F. Pharmacologically inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase-3β ameliorates renal inflammation and nephrotoxicity in an animal model of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, F.; Gao, J.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Hou, X.; Li, L.; Li, C.; et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract ameliorates cisplatin-induced testicular apoptosis via PI3K/Akt/mTOR and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways in rats. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwana, H.; Terada, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Okado, T.; Penninger, J.; Irie-Sasaki, J.; Sasaki, T.; Sasaki, S. The phosphoinositide-3 kinase γ–Akt pathway mediates renal tubular injury in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, T.; Sun, J.; Luo, J.; Shu, G.; Wang, S.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. MiR-125b-2 knockout in testis is associated with targeting to the PAP gene, mitochondrial copy number, and impaired sperm quality. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Yu, Q.; Tan, W.-F.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Ma, H. MicroRNA-125b mimic inhibits ischemia reperfusion-induced neuroinflammation and aberrant p53 apoptotic signalling activation through targeting TP53INP1. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 74, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; He, S.; Wu, K.; Wei, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, Q.; Lian, S.; Wang, L.; Wan, F.; Peng, F.; et al. MiR-125b-5p ameliorates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats by suppressing ferroptosis via the regulation of the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, C. Ferroptosis contributing to cardiomyocyte injury induced by silica nanoparticles via miR-125b-2-3p/HO-1 signaling. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2024, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, M.; Han, Y. MiR-125b-5p ameliorates ox-LDL-induced vascular endothelial cell dysfunction by negatively regulating TNFSF4/TLR4/NF-κB signaling. BMC Biotechnol. 2025, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmiki, S.; Ahuja, V.; Puri, N.; Paul, J. miR-125b and miR-223 contribute to inflammation by targeting the key molecules of NFκB pathway. Front. Med. 2020, 6, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Altındağ, F. Sinapic acid ameliorates cisplatin-induced disruptions in testicular steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis by modulating androgen receptor, proliferating cell nuclear antigen and apoptosis in male rats. Andrologia 2022, 54, e14369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M.J.; Negm, W.A.; Saad, H.M.; Salem, E.A.; Hussein, I.A.; Ibrahim, H.A. Fenofibrate and Diosmetin in a rat model of testicular toxicity: New insight on their protective mechanism through PPAR-α/NRF-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Morris, G.F. p53-Mediated regulation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzgummer, S.; Bizzaro, N. The PCNA antigen. Riv. Ital. Med. Lab. 2005, 1, 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cazzalini, O.; Sommatis, S.; Tillhon, M.; Dutto, I.; Bachi, A.; Rapp, A.; Nardo, T.; Scovassi, A.I.; Necchi, D.; Cardoso, M.C.; et al. CBP and p300 acetylate PCNA to link its degradation with nucleotide excision repair synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8433–8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Ortega, J.; Gu, L.; Chang, Z.; Li, G.M. Phosphorylation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen promotes cancer progression by activating the ATM/Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 7037–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Chang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, Q. Post-translational modifications of proliferating cell nuclear antigen: A key signal integrator for DNA damage response (review). Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, H.; Mahmoud, M.; Mahmoud, H. Chemical studies and phytochemical screening of Grape seeds (Vitis vinifera L.). Minia J. Agric. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 313–325. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Toledo, R.T. Oxygen radical absorbance capacities of grape/wine industry byproducts and effect of solvent type on extraction of grape seed polyphenols. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.R.; McWhinney, B.C. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry: A Paradigm Shift in Toxicology Screening Applications. Clin. Biochemist. Rev. 2019, 40, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chis, I.C.; Ungureanu, M.I.; Marton, A.; Simedrea, R.; Muresan, A.; Postescu, I.D.; Decea, N. Antioxidant effects of a grape seed extract in a rat model of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2009, 6, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raafat, M.H.; Hamam, G.G. The possible protective role of royal jelly against cisplatin-induced testicular lesions in adult albino rats: A histological and immunohistochemical study. Egypt. J. Histol. 2012, 35, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, H.; Fuquay, J. Applied Animal Reproduction; Reston Publishing Co. Inc.: Reston, VA, USA, 1980; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tietz, N.W. Clinical Guide to Laboratory Tests; W.B. Saunders, Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995; p. 1096. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, H.H.; Hadley, M. [43] Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid Peroxidation. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 186, pp. 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikimi, M.; Rao, N.A.; Yagi, K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1972, 46, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, R.F.; Sizer, I.W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 1952, 195, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, O.W. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal. Biochem. 1980, 106, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohé, L.; Günzler, W.A. [12] Assays of glutathione peroxidase. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvarna, K.S.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, M.J.; Nishida, M.; Rabinowitz, R.; Cockett, A.T. Histological changes occurring in the contralateral testes of prepubertal rats subjected to various durations of unilateral spermatic cord torsion. J. Urol. 1985, 133, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang-Cong, T.; Nguyen-Thanh, T. Testicular histopathology and spermatogenesis in mice with scrotal heat stress. In Male Reproductive Anatomy; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Olivier, A.K.; Meyerholz, D.K. Principles for valid histopathologic scoring in research. Vet. Pathol. 2013, 50, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbs, D.J. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry E-Book: Theranostic and Genomic Applications; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Festing, M.F.; Altman, D.G. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | RT (min) | Precursor, m/z [M-H]− | Error (ppm) | Tentative Assignment (Compound Name) | Molecular Formula | Ontology | Confidence Level | Basis for Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.57 | 389.1260 | 3.2 | Resveratroloside (Resveratrol glycoside) | C20H22O8 | Stilbenoid glucoside | Level 2 | Resveratrol fragments + sugar neutral loss |

| 2 | 0.59 | 451.1235 | −2.4 | Catechin 5-O-glucoside | C21H24O11 | Flavanol glucoside | Level 3 | Aglycone confirmed; glycosylation position uncertain |

| 3 | 0.72 | 289.0706 | −4.0 | Catechin (Cianidanol) | C15H14O6 | Flavanol | Level 2 | Strong library MS/MS match |

| 4 | 1.24 | 355.1042 | 2.0 | Ferulic acid β-glucoside | C16H20O9 | Phenolic glycosides | Level 2 | Ferulic acid diagnostic ions + sugar loss |

| 5 | 1.62 | 353.0884 | 1.6 | Chlorogensaure (Neochlorogenic acid) | C16H18O9 | Phenolic acids | Level 2 | Characteristic caffeoylquinic acid fragmentation |

| 6 | 1.84 | 771.1996 | 0.8 | Quercetin 3-O-gentiobioside-7-O-rhamnoside | C33H40O21 | Flavonol glycosides | Level 3 | Multiglycosylation prevents structural confirmation |

| 7 | 2.15 | 193.0515 | 4.5 | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | Ferulic acids | Level 2 | Excellent match with libraries |

| 8 | 3.23 | 579.1363 | 1.3 | Kaempferol 3-O-α-arabinopyranosyl (1‴-6″)-β- glucopyranoside | C26H28O15 | Flavonol O-glycosides | Level 3 | Linkage and sugar identity tentative |

| 9 | 3.58 | 609.1465 | 0.7 | kaempferol 3-O-sophoroside | C27H30O16 | Flavonol O-glycosides | Level 2/3 | Aglycone clear; disaccharide linkage tentative |

| 10 | 3.68 | 801.2086 | −1.1 | Isorhamnetin 3-gentiobioside-7-glucoside | C34H42O22 | Flavonol Glycosides | Level 3 | Multiple sugars; tentative configuration |

| 11 | 3.69 | 755.2033 | −1.0 | Isorhamnetin 3-xylosyl-(1-2)-glucoside-7-rhamnoside | C33H40O20 | Methoxyflavonol Glycosides | Level 3 | Complex glycoside; tentative |

| 12 | 3.72 | 563.1416 | 1.7 | Kaempferol 3-O- α-L-rhamnosyl (1-2)β-D-arabinoside | C26H28O14 | Flavonol Glycosides | Level 3 | Class-level identification |

| 13 | 3.93 | 447.0942 | 2.0 | Luteolin 4′-β-D-O-glucoside | C21H20O11 | Flavone Glycoside | Level 2/3 | Luteolin fragments clear; position partially tentative |

| 14 | 4.04 | 593.1520 | 1.3 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucosyl-(1-2)-rhamnoside | C27H30O15 | Flavonol Glycoside | Level 3 | Sugar linkage unresolved |

| 15 | 4.07 | 197.0465 | 4.9 | Syringic acid | C9H10O5 | Gallic acid derivative | Level 2 | Simple phenolic; strong match |

| 16 | 4.08 | 739.2086 | −0.6 | Kaempferol 3-neohesperidoside-7-rhamnoside | C33H40O19 | Flavonol O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Multiglycosylated flavonol |

| 17 | 4.11 | 447.0940 | 1.5 | Luteolin 3′-glucoside (Dracocephaloside) | C21H20O11 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 2 | Known MS/MS pattern |

| 18 | 4.16 | 725.1940 | 0.8 | Kaempferol 3-apioside-7-rhamnosyl-(1-6)-galactoside | C32H38O19 | Flavonol O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Multiple sugars; class-level identification |

| 19 | 4.44 | 577.1571 | 1.4 | kaempferol 3,7-di-O-α-L-rhamnoside | C27H30O14 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Di-glycosylation ambiguous |

| 20 | 4.46 | 1033.2018 | 2.4 | Galloylated prodelphinidin (trimers) | C52H42O23 | Proanthocyanidins | Level 3 | Proanthocyanidin class identifiable; composition tentative |

| 21 | 4.47 | 533.1310 | 1.7 | Apigenin 6-C-alpha-L-arabinopyranosyl-8-C-beta-D-xylopyranoside | C25H26O13 | Flavone C-Glycosides | Level 3 | C-glycoside isomerism unresolved |

| 22 | 4.54 | 431.0996 | 2.9 | Kaempferol-7-O-alpha-L-rhamnoside | C21H20O10 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 2/3 | Good match; position not fully confirmed |

| 23 | 4.64 | 917.2364 | 0.8 | Kaempferol 7-O-(6-trans-caffeoyl)-beta-glucopyranosyl-(1-3)-alpha-rhamnopyranoside-3-O-beta-glucopyranoside | C42H46O23 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Highly complex; class-level |

| 24 | 4.71 | 593.1529 | 2.9 | Apigenin-7-O-gentiobioside | C27H30O15 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 2/3 | Aglycone clear; sugar linkage tentative |

| 25 | 4.82 | 901.2410 | 0.2 | Kaempferol 7-O-(6-trans-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranosyl-(1-3)-α-rhamnopyranoside-3-O-β-glucopyranoside | C42H46O22 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Class-level only |

| 26 | 5.20 | 475.1246 | 0.0 | Luteolin 7,3′-dimethyl ether 5-glucoside | C23H24O11 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 2/3 | Known fragmentation; methylation pattern tentative |

| 27 | 6.03 | 431.0988 | 1.1 | kaempferol-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside | C21H20O10 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 2/3 | Common glycoside; minor ambiguity |

| 28 | 6.77 | 301.0344 | −3.1 | Quercetin Dihydrate | C15H10O7 | Flavonols | Level 2 | Aglycone match; hydration commonly observed |

| 29 | 7.28 | 329.0662 | −1.4 | Quercetin 3,4′-dimethyl ether | C17H14O7 | Flavonols | Level 2/3 | Fragmentation consistent with dimethyl quercetin |

| 30 | 7.67 | 461.1093 | 0.7 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-Rhamnoside | C22H22O11 | Flavonol O-Glycosides | Level 2 | Good MS/MS match |

| 31 | 7.68 | 489.1048 | 2.0 | Kaempferol-3-O-(6′′-O-acetyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside | C23H22O12 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Acetylation position uncertain |

| 32 | 11.54 | 499.1236 | −1.0 | Catechin Pentaacetate | C25H24O11 | Flavanols | Level 2/3 | Aglycone identifiable; acetylation tentative |

| 33 | 14.53 | 479.0808 | −1.8 | Myricetin 3-O-α-D-glucopyranoside | C21H20O13 | Flavonol O-Glycosides | Level 2 | Strong literature/library match |

| 34 | 15.22 | 311.1709 | 1.3 | (2S,3R)-trans-Caftaric acid | C13H12O9 | Esterified phenolic acid | Level 2 | Known tartaric ester fragmentation |

| 35 | 15.49 | 479.0853 | 4.6 | Quercetin 6-glucoside | C21H20O13 | Flavonol C-Glycosides | Level 2/3 | Aglycone clear; position tentative |

| 36 | 16.00 | 325.1859 | 2.3 | Trans-p-Coumaric acid 4-glucoside | C15H18O8 | Phenolic glycosides | Level 2 | Clear diagnostic ions |

| 37 | 17.76 | 763.2097 | 0.8 | Kaempferol-3-O-lysimachiatrioside | C35H40O19 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Rare trisaccharide; tentative |

| 38 | 18.73 | 504.1272 | 3.3 | Peonidin 3-O-(6-O-acetyl-β-D-glucoside) | C24H25O12+ | Anthocyanin cation | Level 2/3 | Anthocyanin fragmentation clear; acetylation uncertain |

| 39 | 19.44 | 563.1412 | 1.1 | Kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnosyl (1-2)β-D-xyloside | C26H28O14 | Flavone O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Glycosylation linkage unresolved |

| 40 | 21.65 | 549.0878 | −1.4 | Quercetin 3-O-(6″-o-malonyl)-β-D-glucoside | C24H22O15 | Flavonol O-Glycosides | Level 3 | Malonylation position tentative |

| 41 | 23.87 | 455.3535 | −0.4 | Oleanolic Acid | C30H48O3 | Pentacyclic triterpenoid | Level 2 | Diagnostic triterpenoid MS/MS pattern |

| Gene | Accession No. | Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K | NM_013005.2 | F | TGCTATGCCTGCTCTGTAGTGGT |

| R | GTGTGACATTGAGGGAGTCGTTG | ||

| GSK3B | NM_032080.1 | F | GGAACTCCAACAAGGGAGCA |

| R | TTCGGGGTCGGAAGACCTTA | ||

| ARNTL | NM_024362.2 | F | ACCTCGCAGAATGTCACAGGCA |

| R | CTGAACCATCGACTTCGTAGCG | ||

| ACSL4 | NM_001431651.1 | F | CCTTTGGCTCATGTGCTGGAAC |

| R | GCCATAAGTGTGGGTTTCAGTAC | ||

| COX2 | NM_017232.4 | F | GCGACATACTCAAGCAGGAGCA |

| R | AGTGGTAACCGCTCAGGTGTTG | ||

| miR-125b | MIMAT0000830 | UCCCUGAGACCCUAACUUGUGA | |

| 18s rRNA | NR_046237.2 | F | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mohammed, S.A.A.; Saad, H.M.; Esmail, K.A.; Eliwa, D.; Rohiem, A.H.; Awad, A.A.; El-Adawy, S.A.; Amer, S.S.; Abdelhiee, E.Y. Protection by Vitis vinifera L. Against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Ferroptosis. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010178

Mohammed SAA, Saad HM, Esmail KA, Eliwa D, Rohiem AH, Awad AA, El-Adawy SA, Amer SS, Abdelhiee EY. Protection by Vitis vinifera L. Against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Ferroptosis. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010178

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammed, Salman A. A., Hebatallah M. Saad, Kariman A. Esmail, Duaa Eliwa, Aya H. Rohiem, Amal A. Awad, Samar A. El-Adawy, Shimaa S. Amer, and Ehab Y. Abdelhiee. 2026. "Protection by Vitis vinifera L. Against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Ferroptosis" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010178

APA StyleMohammed, S. A. A., Saad, H. M., Esmail, K. A., Eliwa, D., Rohiem, A. H., Awad, A. A., El-Adawy, S. A., Amer, S. S., & Abdelhiee, E. Y. (2026). Protection by Vitis vinifera L. Against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Injury: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Ferroptosis. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010178