Rebamipide as an Adjunctive Therapy for Gastrointestinal Diseases: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

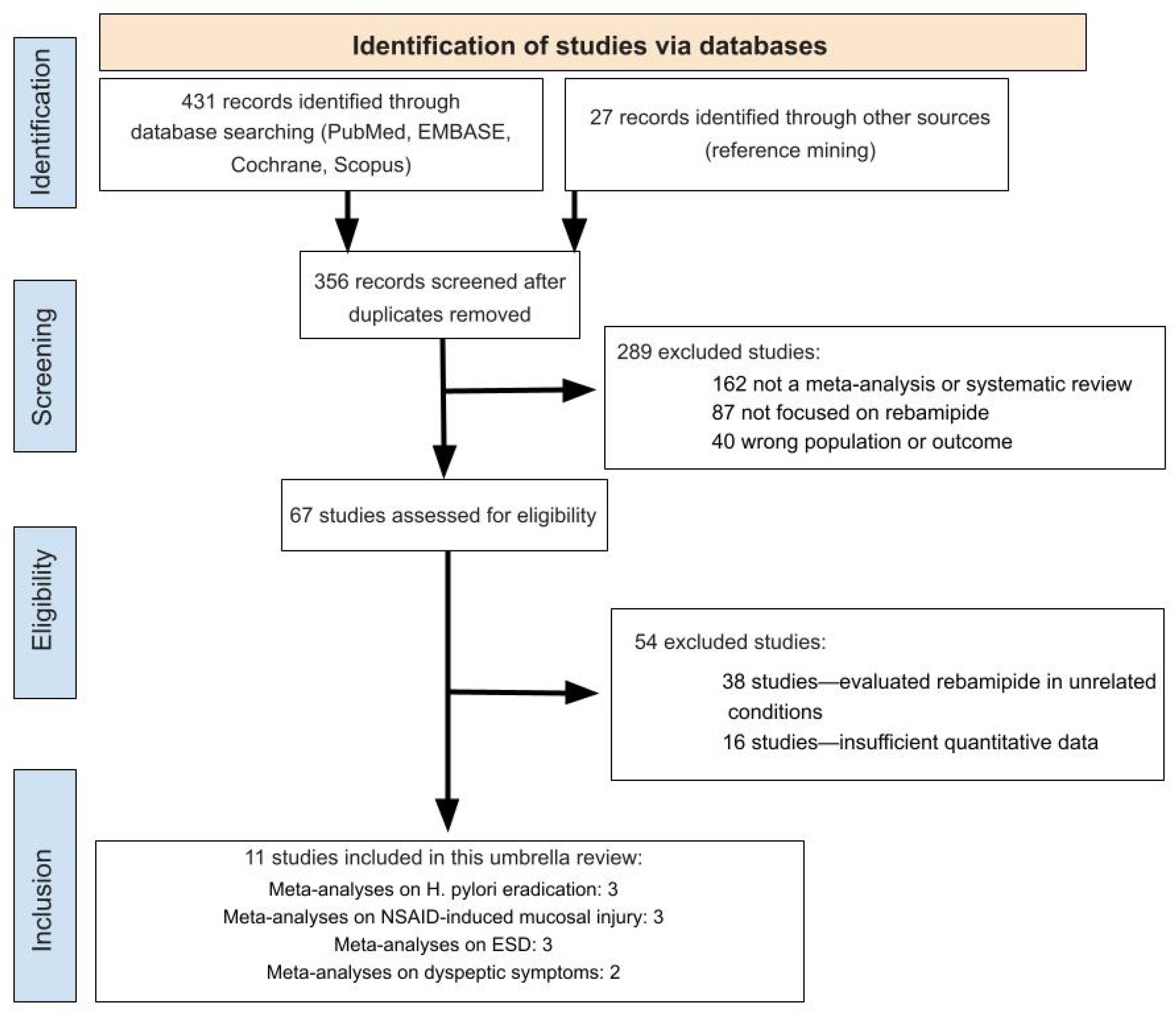

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. ROBIS Assessment

2.3. GROOVE Analysis

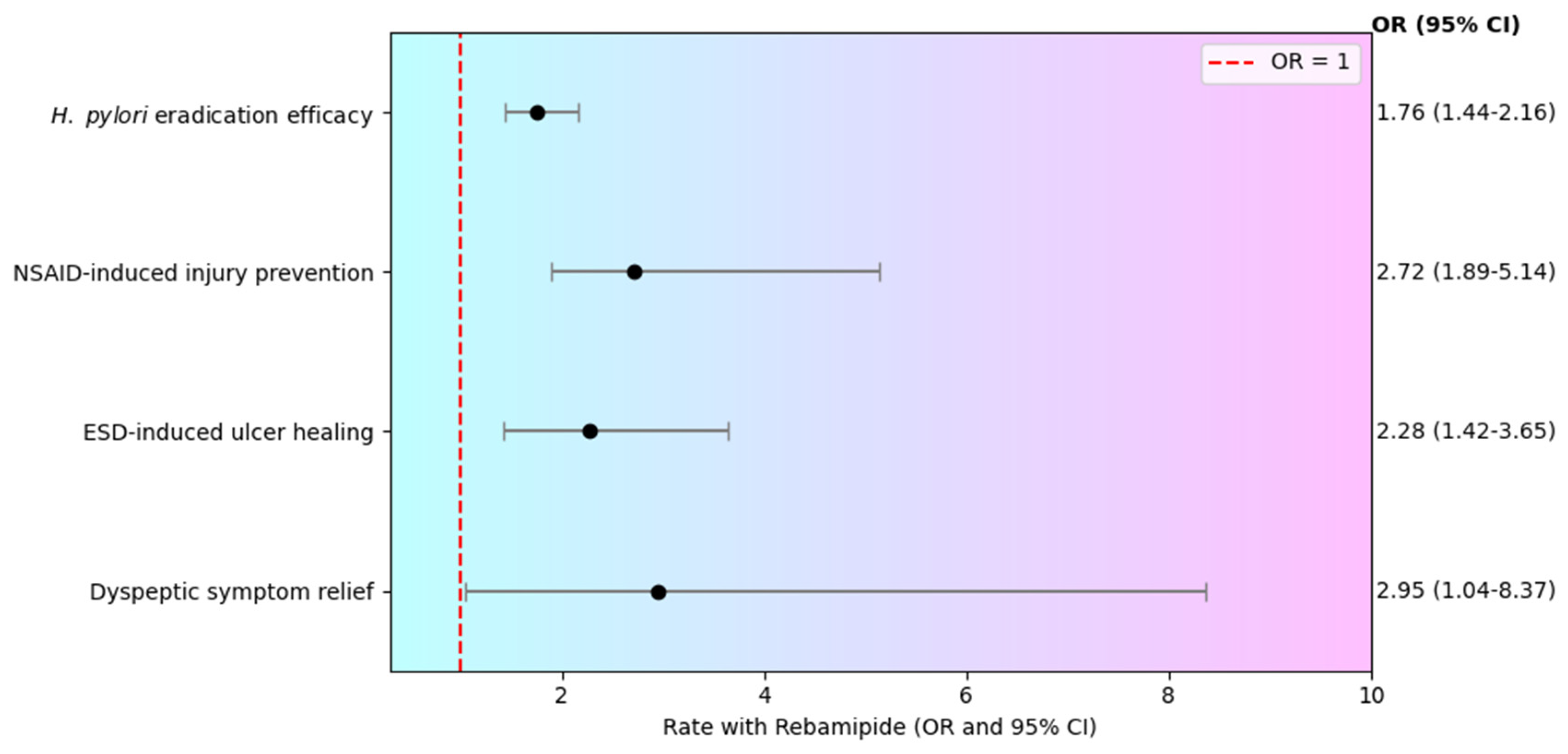

3. Effectiveness of Rebamipide Supplementation

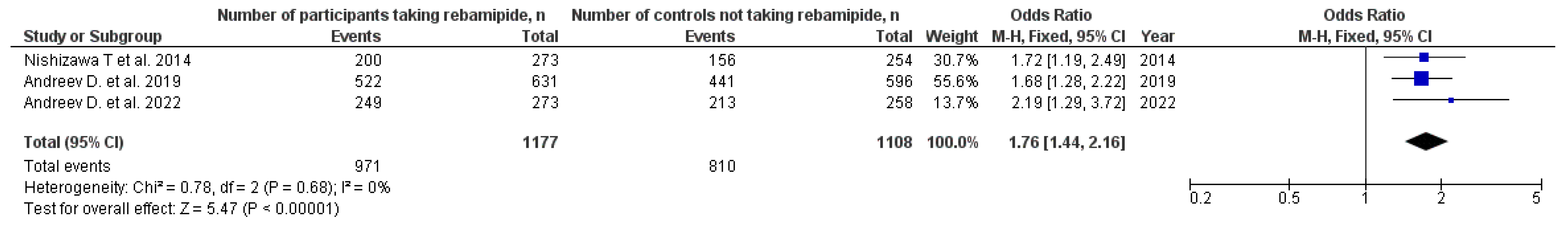

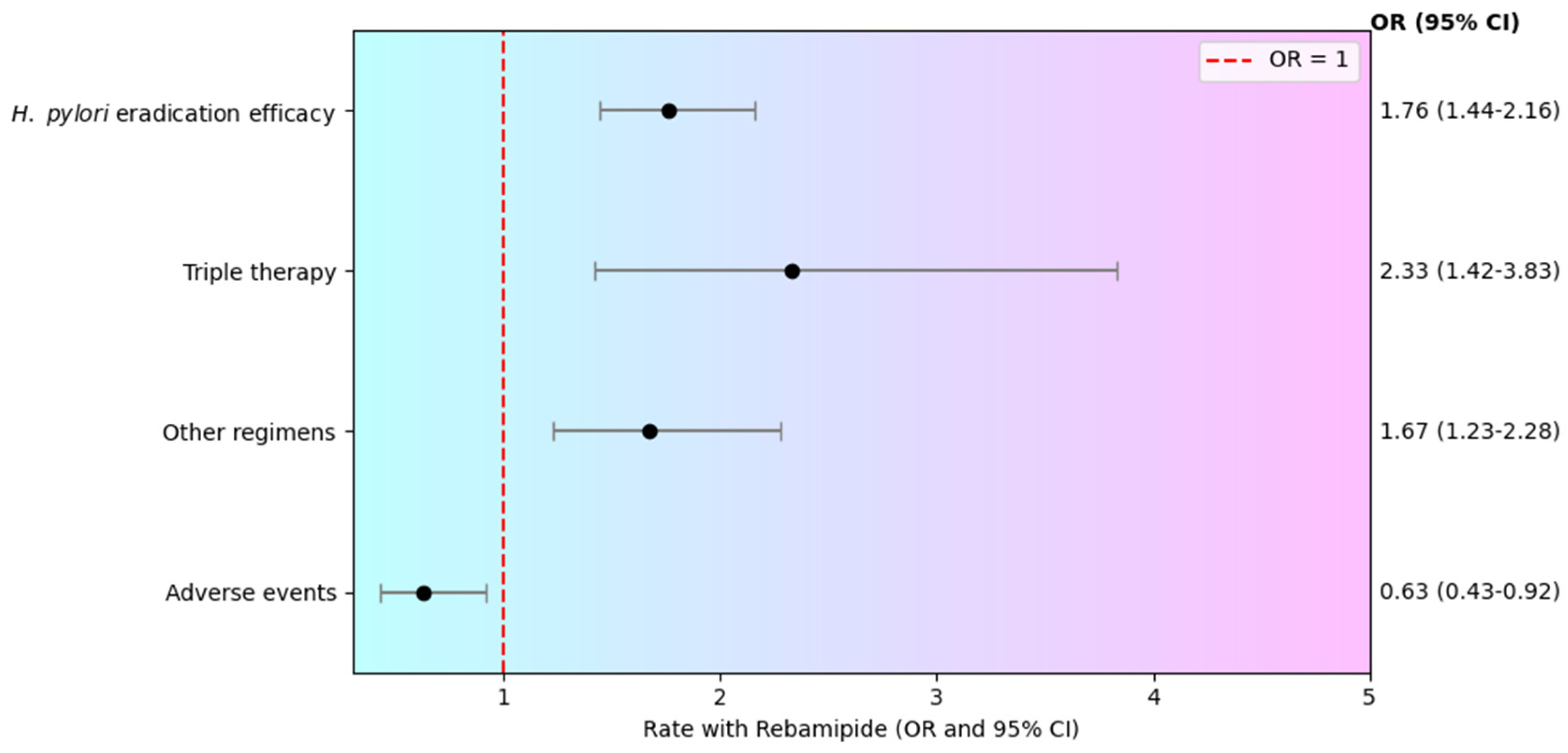

3.1. H. pylori Eradication

3.2. NSAID-Induced Mucosal Injury

3.3. ESD-Induced Ulcer Healing

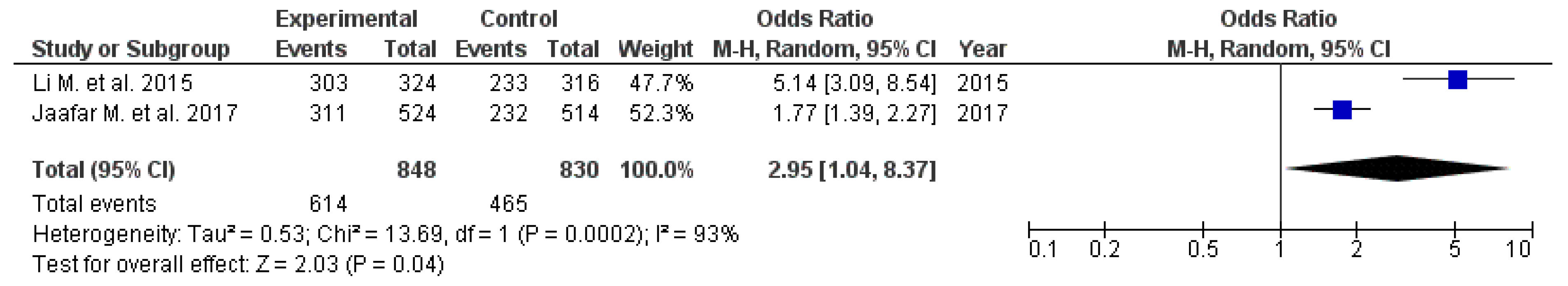

3.4. Management of Dyspeptic Symptoms

4. Discussion

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Search Strategy

5.2. Eligibility Criteria and Quality Assessment

5.3. Risk of Bias Evaluation

5.4. Overlap of Primary Studies

5.5. Data Extraction

5.6. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.; Yin, L.; Nesheli, D.N.; Yu, J.; Franzén, J.; Ye, W. Overall and cause-specific mortality among patients diagnosed with gastric precancerous lesions in Sweden between 1979 and 2014: An observational cohort study. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.A.; Lee, D.-K. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Peptic Ulcer Disease. Korean J. Helicobacter Up. Gastrointest. Res. 2025, 25, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.C.; Yuan, Y.; Park, J.Y.; Forman, D.; Moayyedi, P. Eradication Therapy to Prevent Gastric Cancer in Helicobacter pylori–Positive Individuals: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.J.Y.; Kuipers, E.J.; El-Serag, H.B. Systematic review: The global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Farooq, U.; Zahid, S.; Okolo, P.I. Endoscopic suturing for mucosal defect closure following endoscopic submucosal dissection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 2024, 12, E1150–E1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Tang, M.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Y. The relationship between the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the occurrence of stomach cancer: An updated meta-analysis and systemic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, S.; Hirabayashi, S.; Oda, I.; Ono, H.; Nashimoto, A.; Isobe, Y.; Miyashiro, I.; Tsujitani, S.; Seto, Y.; Fukagawa, T.; et al. Gastric cancer treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection or endoscopic mucosal resection in Japan from 2004 through 2006: JGCA nationwide registry conducted in 2013. Gastric Cancer 2017, 20, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, T.; Kato, M.; Yoshio, T.; Akasaka, T.; Yoshioka, T.; Michida, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Hayashi, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Tsujii, M.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in early gastric cancer in elderly patients and comorbid conditions. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 7, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Management of the complications of endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, S.; Tramèr, M.R.; Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; McQuay, H.J. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: Effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kak, M. Rebamipide in gastric mucosal protection and healing: An Asian perspective. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 16, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, D.N.; Maev, I.V.; Dicheva, D.T. Efficiency of the Inclusion of Rebamipide in the Eradication Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cion, R.I.A.; Juyad, I.G.A.; Yasay, E.B. Efficacy of Rebamipide in the Prevention of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Gastrointestinal Mucosal Breaks: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Ye, C.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Song, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Dong, W. Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) Plus Rebamipide for Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection-Induced Ulcers: A Meta-Analysis. Intern. Med. 2014, 53, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, T.; Higuchi, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Tominaga, K.; Sasaki, E.; Oshitani, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Tarnawski, A.S. 15th Anniversary of Rebamipide: Looking Ahead to the New Mechanisms and New Applications. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2005, 50, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakulina, N.V.; Tikhonov, S.V.; Okovityi, S.V.; Lutaenko, E.A.; Bolshakov, A.O.; Prikhodko, V.A.; Nekrasova, A.S. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rebamipide. New possibilities of therapy: A review. Ter. Arkh. 2023, 94, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, T.; Nishizawa, Y.; Yahagi, N.; Kanai, T.; Takahashi, M.; Suzuki, H. Effect of supplementation with rebamipide for Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreev, D.N.; Maev, I.V.; Bordin, D.S.; Lyamina, S.V.; Dicheva, D.T.; Fomenko, A.K.; Bagdasarian, A.S. Effectiveness of Rebamipide as a part of the Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Russia: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Cons. Medicum 2022, 24, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Qing, Q.; Bai, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Rebamipide Helps Defend Against Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Induced Gastroenteropathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.; Park, J.M.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, B.-W.; Choi, M.-G.; Kim, N.J. Drugs Effective for Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs or Aspirin-Induced Small Bowel Injuries. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2024, 58, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kanai, T.; Yahagi, N. Proton pump inhibitor alone vs proton pump inhibitor plus mucosal protective agents for endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2015, 56, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xiong, Z.; Geng, X.; Cui, M. Rebamipide with Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) Versus PPIs Alone for the Treatment of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection-Induced Ulcers: A Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7196782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yin, T.; Lin, B. Rebamipide for chronic gastritis: A meta-analysis. Chin. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 24, 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.H.; Safi, S.Z.; Tan, M.-P.; Rampal, S.; Mahadeva, S. Efficacy of Rebamipide in Organic and Functional Dyspepsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.R.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.G. The risk of pulmonary adverse drug reactions of rebamipide and other drugs for acid-related diseases: An analysis of the national pharmacovigilance database in South Korea. J. Dig. Dis. 2022, 23, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genta, R.M. Review article: The role of rebamipide in the management of inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamate, S.; Ishiguro, C.; Fukuda, H.; Hamai, S.; Nakashima, Y. Continuous co-prescription of rebamipide prevents upper gastrointestinal bleeding in NSAID use for orthopaedic conditions: A nested case-control study using the LIFE Study database. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyaglova, M.Y.; Knyazev, O.V.; Parfenov, A.I. Pharmacological and clinical feature of rebamipide: New therapeutic targets. Ter. Arkh. 2020, 92, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5042, Rebamipide. 2004. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Rebamipide (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Nishimura, Y.; Tagawa, M.; Ito, H.; Tsuruma, K.; Hara, H. Overcoming Obstacles to Drug Repositioning in Japan. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeji, Y.; Urashima, H.; Aoki, A.; Shinohara, H. Rebamipide Increases the Mucin-like Glycoprotein Production in Corneal Epithelial Cells. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 28, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, C.; Jing, L.; Mou, S.; Cao, X.; Yu, Z. Protective effect and mechanism of rebamipide on NSAIDs associated small bowel injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 90, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, A.S.; Chai, J.; Pai, R.; Chiou, S.-K. Rebamipide Activates Genes Encoding Angiogenic Growth Factors and Cox2 and Stimulates Angiogenesis: A Key to Its Ulcer Healing Action? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2004, 49, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, T. Rebamipide promotes healing of colonic ulceration through enhanced epithelial restitution. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, H.; Osada, T.; Nagahara, A.; Ohkusa, T.; Hojo, M.; Tomita, T.; Hori, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, N. Effect of a gastro-protective agent, rebamipide, on symptom improvement in patients with functional dyspepsia: A double-blind placebo-controlled study in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 21, 1826–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, L.; Ceulemans, M.; Schol, J.; Farré, R.; Tack, J.; Vanuytsel, T. The Role of Leaky Gut in Functional Dyspepsia. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 851012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovaleva, A.; Poluektova, E.; Maslennikov, R.; Karchevskaya, A.; Shifrin, O.; Kiryukhin, A.; Tertychnyy, A.; Kovalev, L.; Kovaleva, M.; Lobanova, O.; et al. Effect of Rebamipide on the Intestinal Barrier, Gut Microbiota Structure and Function, and Symptom Severity Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Dyspepsia Overlap: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N.; Kamada, K.; Tomatsuri, N.; Suzuki, T.; Takagi, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Management of Recurrence of Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Synergistic Effect of Rebamipide with 15 mg Lansoprazole. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 3393–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makushina, A.A.; Trukhmanov, A.S.; Storonova, O.A.; Paraskevova, A.V.; Ermishina, P.G.; Mironova, V.A.; Ivashkin, V.T. Changes in esophageal functional state during combined acid-suppressive and epithelial protective therapy in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Voprosy. Detskoj. Dietologii. 2025, 23, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Park, S.-H.; Moon, J.S.; Shin, W.G.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, Y.C.; Lee, D.H.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, H.L.; et al. The Benefits of Combination Therapy with Esomeprazole and Rebamipide in Symptom Improvement in Reflux Esophagitis: An International Multicenter Study. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: A primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. Cmaj 2009, 181, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Cuello, C.; Akl, E.A.; Mustafa, R.A.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Thayer, K.; Morgan, R.L.; Gartlehner, G.; Kunz, R.; Katikireddi, S.V.V.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracchiglione, J.; Meza, N.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Niño de Guzmán, E.; Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X.; Madrid, E. Graphical Representation of Overlap for OVErviews: GROOVE tool. Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Comparison of H. pylori Eradication Rates With and Without Rebamipide | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | Types of included studies and number of included studies, n | Number of participants taking rebamipide, n | Number of participants achieving successful eradication with rebamipide, n | Number of controls not taking rebamipide, n | Number of participants achieving successful eradication without rebamipide, n | Effect Measure | Quality evaluation, AMSTAR-2 | Quality evaluation, Grade |

| Nishizawa T. et al. 2014 [17] | 6 RCTs | 273 | 200 | 254 | 156 | OR 1.74 (95% CI: 1.19–2.53) | Moderate | Low |

| Andreev D. et al. 2019 [12] | 11 RCTs | 631 | 522 | 596 | 441 | OR 1.75 (95% CI: 1.31–2.34) | High | High |

| Andreev D. et al. 2022 [18] | 6 RCTs | 273 | 249 | 258 | 213 | OR 2.16 (95% CI: 1.27–3.69) | Moderate | Moderate |

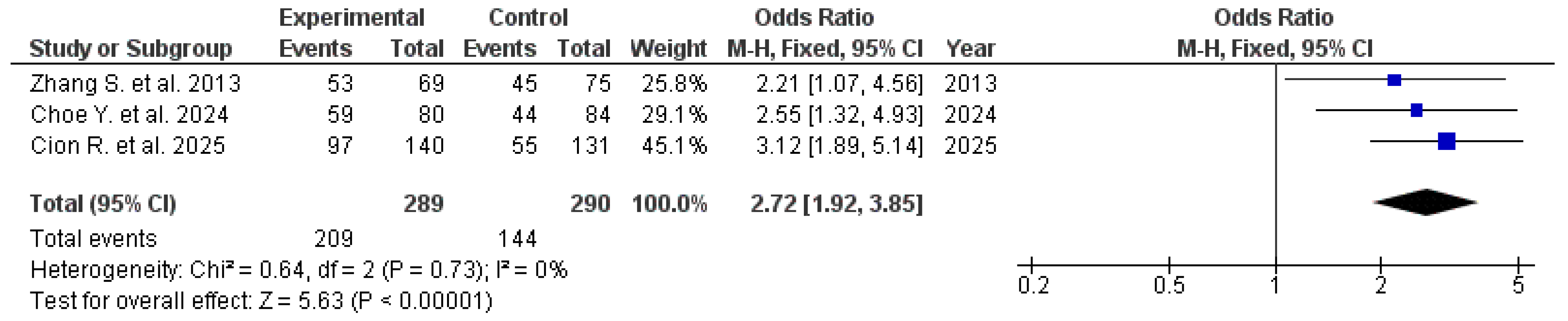

| Effect of Therapy in Patients Receiving Rebamipide vs. Controls During NSAID Therapy | ||||||||

| Author, year | Types of included studies and number of included studies, n | Number of participants taking rebamipide, n | Number of patients without NSAID-induced mucosal injury, n | Number of controls, n | Number of controls without NSAID-induced mucosal injury, n | Effect Measure | Quality evaluation, AMSTAR-2 | Quality evaluation, GRADE |

| Zhang S. et al. 2013 [19] | 15 RCTs | 69 | 53 | 75 | 45 | RR 2.70 (95% CI: 1.02–7.16) | High | Moderate |

| Choe Y. 2024 [20] | 5 RCTs | 80 | 59 | 84 | 40 | OR 2.55 (95% CI: 1.32–4.93) | High | Moderate |

| Cion R. et al. 2025 [13] | 13 RCTs | 140 | 97 | 131 | 55 | OR 3.12 (95% CI: 1.89–5.14) | Moderate | Moderate |

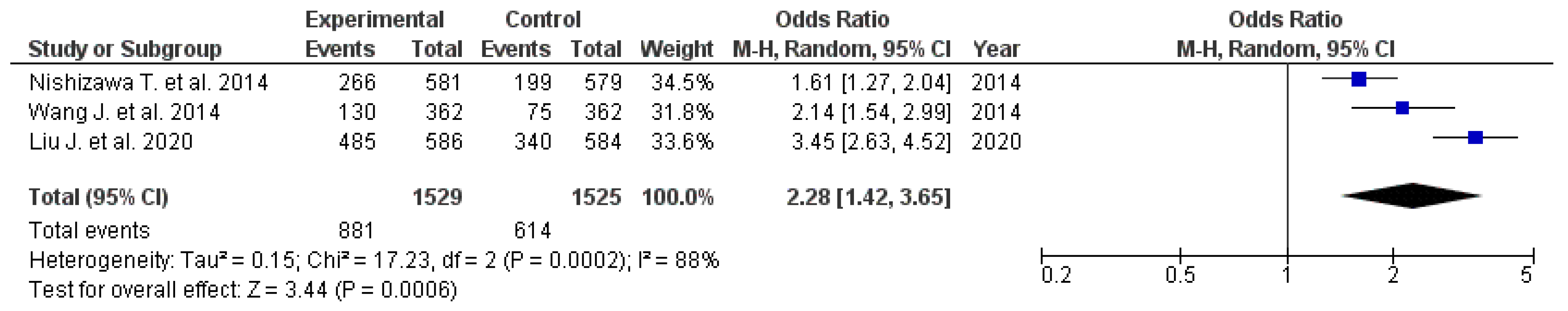

| Impact of Rebamipide Addition to PPI Therapy on ESD-Induced Ulcer Healing | ||||||||

| Author, year | Types of included studies and number of included studies, n | Participants Receiving Rebamipide + PPI, n | Pooled healing rates (Rebamipide + PPI), n | Participants Receiving PPI Only, n | Pooled healing rates (PPI Only), n | Effect Measure | Quality evaluation, AMSTAR-2 | Quality evaluation, GRADE |

| Nishizawa T. et al. 2015 [21] | 11 RCTs | 581 | 266 | 579 | 199 | OR 2.28 (95% CI: 1.57–3.31) | Moderate | Low |

| Wang J. et al. 2014 [14] | 6 RCTs | 362 | 130 | 362 | 75 | OR 2.40 (95% CI: 1.68–3.44) | High | Moderate |

| Liu J. et al. 2020 [22] | 9 RCTs | 586 | 485 | 584 | 340 | RR 1.42 (95% CI: 1.13–1.78) | High | High |

| The Effect of Rebamipide on Dyspeptic Symptoms | ||||||||

| Author, year | Types of included studies and number of included studies, n | Number of participants taking rebamipide, n | Number of patients who had relieved symptoms, n | Number of controls, n | Number of controls who had relieved symptoms, n | Effect Measure | Quality evaluation, AMSTAR-2 | Quality evaluation, GRADE |

| Li M. et al. 2015 [23] | 12 RCTs | 324 | 303 | 316 | 233 | RR 1.23 (95% CI: 1.06–1.41) | Moderate | High |

| Jaafar M. et al. 2018 [24] | 17 RCTs | 524 | 311 | 514 | 232 | OR 1.77 (95% CI: 1.39–2.27) | Low | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maev, I.V.; Khurmatullina, A.R.; Andreev, D.N.; Zaborovsky, A.V.; Kucheryavyy, Y.A.; Sokolov, P.S.; Beliy, P.A. Rebamipide as an Adjunctive Therapy for Gastrointestinal Diseases: An Umbrella Review. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010144

Maev IV, Khurmatullina AR, Andreev DN, Zaborovsky AV, Kucheryavyy YA, Sokolov PS, Beliy PA. Rebamipide as an Adjunctive Therapy for Gastrointestinal Diseases: An Umbrella Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaev, Igor V., Alsu R. Khurmatullina, Dmitrii N. Andreev, Andrew V. Zaborovsky, Yury A. Kucheryavyy, Philipp S. Sokolov, and Petr A. Beliy. 2026. "Rebamipide as an Adjunctive Therapy for Gastrointestinal Diseases: An Umbrella Review" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010144

APA StyleMaev, I. V., Khurmatullina, A. R., Andreev, D. N., Zaborovsky, A. V., Kucheryavyy, Y. A., Sokolov, P. S., & Beliy, P. A. (2026). Rebamipide as an Adjunctive Therapy for Gastrointestinal Diseases: An Umbrella Review. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010144