Vatairea Genus as a Potential Therapeutic Agent—A Comprehensive Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

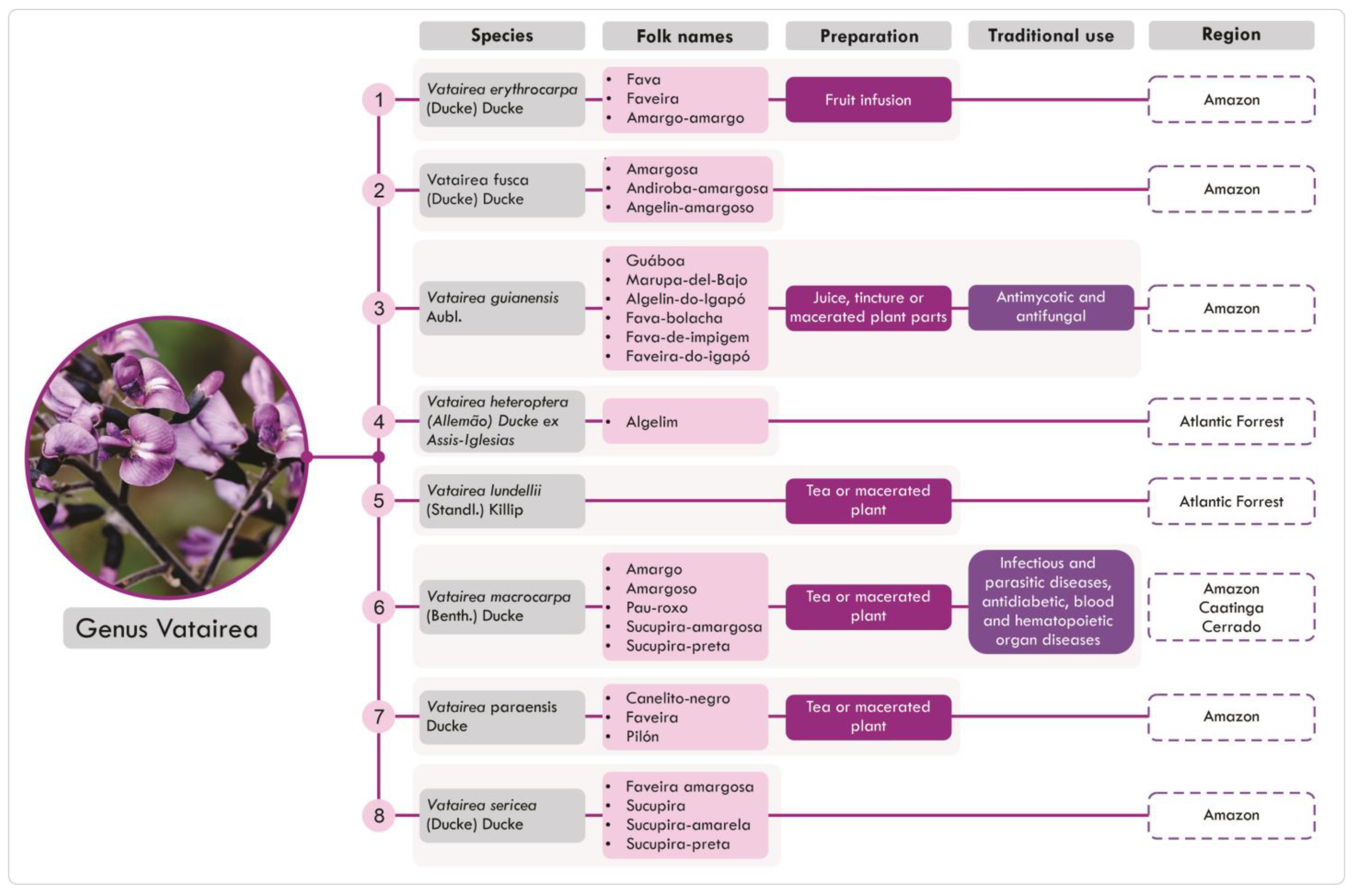

2. Ethnobotanical Features

2.1. Taxonomy and Botanical Aspects

2.2. Distribution and Traditional Uses

3. Phytochemical Aspects

3.1. Vatairea guianensis

3.2. Vatairea macrocarpa

3.3. Vatairea heteroptera

4. Pharmacological Properties

4.1. Toxicity Studies

4.2. Pharmacological Studies

4.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

4.2.2. Antifungal Activity

4.2.3. Endocrine System

4.2.4. Cardiovascular and Renal Systems

4.2.5. Immune System

4.2.6. Central Nervous System

4.2.7. Nociception

4.2.8. Wound-Healing

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braga, F.C. Brazilian traditional medicine: Historical basis, features and potentialities for pharmaceutical development. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2021, 8, S44–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REFLORA. Public Search of Virtual Herbarium. Available online: https://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herbarioVirtual/ (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Miguéis, G.d.S.; da Silva, R.H.; Júnior, G.A.D.; Guarim-Neto, G. Plants used by the rural community of Bananal, Mato Grosso, Brazil: Aspects of popular knowledge. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, R.V.; Bieski, I.G.C.; Balogun, S.O.; Martins, D.T.d.O. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Ribeirinhos in the North Araguaia microregion, Mato Grosso, Brazil. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 205, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, L.D.M.; Sousa, L.d.O.F.d.; Oliveira, F.F.M.; Camacho, R.G.V.; de Melo, J.I.M. Fabaceae na Floresta Nacional (FLONA) de Assú, semiárido potiguar, nordeste do Brasil. Rodriguésia 2016, 67, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.S.; Miotto, S. A família Fabaceae no Morro Santana, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: Aspectos taxonômicos e ecológicos. Rev. Bras. Biociências 2013, 11, 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, G.C.; Gomes, J.I.; Hopkins, M.J.G. Estudo anatômico das espécies de Leguminosae comercializadas no estado do Pará como “angelim”. Acta Amaz. 2004, 34, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.B.O.S.; Ramos, G.; Lima, H.C. Flora e Funga do Brasil. 2020. Available online: https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB23208 (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- De Lima, H.C. Revisão Taxonômica Do Gênero Vataireopsis Ducke (LEG. FAB.). Rodriguésia 1980, 32, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropicos. Available online: https://tropicos.org/image/101098123 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Tropicos. Available online: https://tropicos.org/image/100495992 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Plants of the World Online. Plants of the World Online|Kew Science. Available online: http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Grenand, P.; Moretti, C.; Jacquemin, H.; Prévost, M.-F. Pharmacopées Traditionnelles en Guyane. In IRD Éditions eBooks; IRD Éditions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; p. 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W. Antraquinonas de Vatairea guianensis AUBI. (FABACEAE). Available online: https://repositorio.inpa.gov.br/bitstream/1/13726/1/artigo-inpa.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Araújo, G.d.M.L.d.; de Araújo, N.D.; de Farias, R.P.; Cavalcanti, F.C.N.; Lima, M.D.L.F.; Braz, R.A.F.d.S. Micoses superficiais na Paraíba: Análise comparativa e revisão literária. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2010, 85, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.T.L.; Medeiros, B.J.S.; dos Santos, K.C.; Pereira-Filho, R.; de Albuquerque-Júnior, R.L.C.; Sousa, P.J.d.C.; Carvalho, J.C.T. Topical healing activity of the hydroethanolic extract from the seeds of Vatairea guianensis (AUBLET) Research Article. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2011, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.A.; Segovia, J.F.; Sousa, V.Y.; Mata, E.C.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Bezerra, R.M.; Junior, P.O.; Kanzaki, L.I. Antimicrobial activity of amazonian medicinal plants. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottobelli, I.; Facundo, V.A.; Zuliani, J.; Luz, C.C.; Brasil, H.O.B.; Militão, J.S.L.T.; Braz-Filho, R. Estudo químico de duas plantas medicinais da amazônia: Philodendron scabrum k. Krause (araceae) e Vatairea guianensis aubl. (fabaceae). Acta Amaz. 2011, 41, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.F.; Marinho, V.H.S.; da Silva, G.A.; Costa-Júnior, L.M.; da Silva, J.K.R.; Bastos, G.N.T.; Arruda, A.C.; da Silva, M.N.; Arruda, M.S.P. New Isoflavones from the Leaves of Vatairea guianensis Aublé. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2013, 24, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, D.B.; Da Costa, R.C.; Araújo, R.M.; De Paula, J.E.; Silveira, E.R.; Filho, R.B.; Espíndola, L.S. Activity of Fabaceae species extracts against fungi and Leishmania: Vatacarpan as a novel potent anti-Candida agent. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Cruz, E.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, F.; Valdez-Hernández, J.I.; Mendoza-Cruz, E.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, F.; Valdez-Hernández, J.I. Actividad de la guacamaya escarlata Ara macao cyanoptera (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae) y características estructurales de su hábitat en Marqués de Comillas, Chiapas. Acta Zool. Mex. 2017, 33, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.; da Silva, G.; Arruda, A.; da Silva, M.; Santos, A.; Grisólia, D.; Silva, M.; Salgado, C.; Arruda, M.S. A New Prenylisoflavone from the Antifungal Extract of Leaves of Vatairea guianensis Aubl. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 28, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, N.Z.T.; Lima, J.C.d.S.; da Silva, R.M.; Espinosa, M.M.; Martins, D.T.d.O. Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas popularmente utilizadas como antiúlceras e antiinflamatórias pela comunidade de Pirizal, Nossa Senhora do Livramento-MT, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2009, 19, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, E.; Silva-Filho, S.E.; Radai, J.A.S.; Arena, A.C.; Fraga, T.L.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Croda, J.; Kassuya, C.A.L. Anti-inflammatory properties of ethanolic extract from Vatairea macrocarpa leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.R.; Santos, A.M.; Barreto, F.S.; Costa, P.M.; Roma, R.R.; Rocha, B.A.; Oliveira, C.V.; Duarte, A.E.; Pessoa, C.; Teixeira, C.S. In vitro antiproliferative effects of Vatairea macrocarpa (Benth.) Ducke lectin on human tumor cell lines and in vivo evaluation of its toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 190, 114815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.C.; dos Santos, M.P.; Grigulo, R.; Lima, L.L.; Martins, D.T.; Lima, J.C.; Stoppiglia, L.F.; Lopes, C.F.; Kawashita, N.H. Antidiabetic activity of Vatairea macrocarpa extract in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviloni, P.D.; dos Santos, M.P.; Aiko, G.M.; Reis, S.R.d.L.; Latorraca, M.Q.; da Silva, V.C.; Dall’oglio, E.L.; Júnior, P.T.d.S.; Lopes, C.F.; Baviera, A.M.; et al. Mechanism of anti-hyperglycemic action of Vatairea macrocarpa (Leguminosae): Investigation in peripheral tissues. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 131, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddouks, M.; Bidi, A.; El Bouhali, B.; Hajji, L.; Zeggwagh, N.A. Antidiabetic plants improving insulin sensitivity. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatupang, M.H.; Dietrichs, H.H.; Gottwald, H. Über die hautreizenden Stoffe in Vatairea guianensis Aubl. Holzforschung 1967, 21, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.F.; da Silva, J.K.R.; da Silva, G.A.; Arruda, A.C.; da Silva, M.N.; Arruda, M.S.P. Chemical Study and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Potential of Sapwood of Vatairea guianensis Aubl. Rev. Virtual Quim. 2015, 7, 1893–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formiga, M.D.; Gottlieb, O.R.; Mendes, P.H.; Koketsu, M.; de Almieda, M.L.; Pereira, M.O.d.S.; Magalhães, M.T. Constituents of Brazilian leguminosae. Phytochemistry 1975, 14, 828–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, V.N.; Verma, P.; Khurana, A. Anthralin/dithranol in dermatology. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, e449–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, P.O.; Campos, P.R.b.; Noffs, M.A.; Oliveira, J.G.; Shimizu, M.T.; da Silva, D.M. Application of microbial lipases to concentrate polyunsaturated fatty acids. Química Nova 2003, 26, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenborre, G.; Smagghe, G.; Van Damme, E.J. Plant lectins as defense proteins against phytophagous insects. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1538–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeiner, P.; Mislovičová, D.; Tkáč, J.; Švitel, J.; Pätoprstý, V.; Hrabárová, E.; Kogan, G.; Kožár, T. Lectinomics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwierzina, H.; Bergmann, L.; Fiebig, H.; Aamdal, S.; Schöffski, P.; Witthohn, K.; Lentzen, H. The preclinical and clinical activity of aviscumine: A potential anticancer drug. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, C.; Lehr, C.-M.; Woodley, J.F. Lectin-mediated drug targeting: History and applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003, 56, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.C.; Nagano, C.S.; Souza, L.A.; Nascimento, K.S.; Isídro, R.; Delatorre, P.; Rocha, B.A.M.; Sampaio, A.H.; Assreuy, A.M.S.; Pires, A.F.; et al. Purification and primary structure determination of a galactose-specific lectin from Vatairea guianensis Aublet seeds that exhibits vasorelaxant effect. Process. Biochem. 2012, 47, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavada, B.S.; Osterne, V.J.S.; Pinto-Junior, V.R.; Souza, L.A.G.; Lossio, C.F.; Silva, M.T.L.; Correia-Neto, C.; Oliveira, M.V.; Correia, J.L.A.; Neco, A.H.B.; et al. Molecular dynamics and binding energy analysis of Vatairea guianensis lectin: A new tool for cancer studies. J. Mol. Model. 2020, 26, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.A.; Arruda, F.V.S.; Carneiro, V.A.; Silva, H.C.; Nascimento, K.S.; Sampaio, A.H.; Cavada, B.; Teixeira, E.H.; Henriques, M.; Pereira, M.O. Effect of Algae and Plant Lectins on Planktonic Growth and Biofilm Formation in Clinically Relevant Bacteria and Yeasts. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 365272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.; Napimoga, M.; Carneiro, V.; de Oliveira, T.; Cunha, R.; Havt, A.; Martins, J.; Pinto, V.; Goncalves, R.; Cavada, B. In vitro inhibition of Streptococci binding to enamel acquired pellicle by Plant Lectins. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.F.; Costa, M.S.; Campina, F.F.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Santos, A.L.E.; Pereira, F.M.; Batista, K.L.R.; Silva, R.C.; Pereira, R.O.; Rocha, B.A.M.; et al. The Galactose-Binding Lectin Isolated from Vatairea macrocarpa Seeds Enhances the Effect of Antibiotics Against Staphylococcus aureus–Resistant Strain. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 12, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véras, J.H.; Cardoso, C.G.; Puga, S.C.; Bisneto, A.V.d.M.; Roma, R.R.; Silva, R.R.S.; Teixeira, C.S.; Chen-Chen, L. Lactose-binding lectin from Vatairea macrocarpa seeds induces in vivo angiogenesis via VEGF and TNF-ɑ expression and modulates in vitro doxorubicin-induced genotoxicity. Biochimie 2022, 194, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, N.Z.T.; Júnior, I.F.S.; Lima, J.C.S.; Colodel, E.M.; Martins, D.T.O. Hippocratic screening and subchronic oral toxicity assessments of the methanol extract of Vatairea macrocarpa heartwood in rodents. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2012, 22, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.T.L.; Mendonça, L.C.; Chagas Monteiro, M.; Carvalho, J.C.T. Antimicrobial activity of extracts obtained from the seeds of Vatairea guianensis (Aublet). Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2011, 10, 456–462. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, A.M.O.; Havt, A.; Barbosa, P.S.F.; Soares, T.F.; Evangelista, J.S.A.M.; Alencar, N.M.N.; Monteiro, H.S.A.; Martins, A.M.C.; de Menezes, D.B.; Fonteles, M.C.; et al. Renal effects induced by the lectin from Vatairea macrocarpa seeds. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2005, 57, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, N.M.; Assreuy, A.M.; Alencar, V.B.; Melo, S.C.; Ramos, M.V.; Cavada, B.S.; Cunha, F.Q.; Ribeiro, R.A. The galactose-binding lectin from Vatairea macrocarpa seeds induces in vivo neutrophil migration by indirect mechanism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 35, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, N.M.N.; Assreuy, A.M.S.; Havt, A.; Benevides, R.G.; de Moura, T.R.; de Sousa, R.B.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Cunha, F.Q.; Cavada, B.S. Vatairea macrocarpa (Leguminosae) lectin activates cultured macrophages to release chemotactic mediators. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2006, 374, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, G.F.; Osterne, V.J.; Almeida, L.M.; Oliveira, M.V.; Brizeno, L.A.; Pinto-Junior, V.R.; Santiago, M.Q.; Neco, A.H.; Mota, M.R.; Souza, L.A.; et al. Contribution of the carbohydrate-binding ability of Vatairea guianensis lectin to induce edematogenic activity. Biochimie 2017, 140, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.M.; Freitas, A.E.; Peres, T.V.; Rieger, D.K.; Ben, J.; Maestri, M.; Costa, A.P.; Tramontina, A.C.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Rodrigues, A.L.S.; et al. Vatairea macrocarpa Lectin (VML) Induces Depressive-like Behavior and Expression of Neuroinflammatory Markers in Mice. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, G.d.O.; Santos, S.A.A.R.; Bezerra, F.M.D.H.; de Silva, F.E.S.; Ribeiro, A.D.d.C.; Roma, R.R.; Silva, R.R.S.; Santos, M.H.C.; Santos, A.L.E.; Teixeira, C.S.; et al. Is the orofacial antinociceptive effect of lectins intrinsically related to their specificity to monosaccharides? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, J.R.C.; Coelho, C.B.; Campos, A.R.; Moreira, R.d.A.; Monteiro-Moreira, A.C.d.O. Animal Galectins and Plant Lectins as Tools for Studies in Neurosciences. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosso, M.Y.; Chan, K.Y.; Gregory, R.; Chang, C.-W.T. Library Synthesis and Antibacterial Investigation of Cationic Anthraquinone Analogs. ACS Comb. Sci. 2012, 14, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Chu, J.; Cheng, H. Physcion, a novel anthraquinone derivative against Chlamydia psittaci infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 279, 109664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comini, L.R.; Vieyra, F.E.M.; Mignone, R.A.; Páez, P.L.; Mugas, M.L.; Konigheim, B.S.; Cabrera, J.L.; Montoya, S.C.N.; Borsarelli, C.D. Parietin: An efficient photo-screening pigment in vivo with good photosensitizing and photodynamic antibacterial effects in vitro. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2016, 16, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sosa, K.; Villareal-Alvarez, N.; Lübben, P.; Peña-Rodríguez, L.M. Chrysophanol, an Antimicrobial Anthraquinone from the Root Extract of Colubrina greggii. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2020, 50, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.; dos Santos, N.S.S.; Torres, A.; Siqueira, M.; da Cunha, A.; Manzoni, V.; Provasi, P.F.; Gester, R.; Canuto, S. Role of the Solvent and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds in the Antioxidative Mechanism of Prenylisoflavone from Leaves of Vatairea guianensis. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 10807–10816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.V.d.O.; Porto, A.L.F.; Cavalcanti, I.M.F. Potential Application of Combined Therapy with Lectins as a Therapeutic Strategy for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Collection Sites | Plant Parts | Type of Extraction | Phytoconstituents Identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. guianensis | Unspecified | Heartwood | Hot extraction Solvent: benzene | Chrysophanic acid-9-anthrone, physcion-9-anthrone and physcion-10-anthrone | [29] |

| Ilha do Marapatá, Manaus—Brazil | Stem bark | Soxhlet extraction. Solvent: ethanol | Chrysophanol, physcion, emodin, and triterpenes | [14] | |

| Parque Ecológico de Porto Velho, Rondônia—Brazil | Fruits | Essential oil hydrodistillation with ethanol | Aldehydes (hexanal, (2Z)-heptenal, (2E,4E)-decadienal, undecenal, dodecanal) and carboxylic acids (docosahexaenoic acid, hexadecanoic acid, and stearic acid) | [18] | |

| Belém, Pará—Brazil | Leaves | Maceration extraction; Solvent: ethanol | Chrysophanol and physcion | [19] | |

| Maceration extraction; Solvent: ethanol | 5,3′-dihydroxy-4′-methoxy-2″,2″-dimethylpyrano-(5″,6″:8,7)-isoflavone; 5,7-dihydroxy-3′,4′-methylenedioxy-8-prenyl-isoflavone; 5,3′-dihydroxy-4′-methoxy-7-O-β-glucopyranoside-8-prenyl-isoflavone; and derrone | ||||

| Belém, Pará—Brazil | Sapwood | Maceration extraction; Solvent: ethanol | Crysophanol, physcion, formononetin, bolusantol D, betulinic acid, sitosterol, and stigmasterol | [30] | |

| Belém, Pará—Brazil | Leaves | Maceration extraction; Solvent: ethanol | 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxy-8-prenyl-isoflavone; upiwighteone; and 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-3′-methoxy-8-prenyl isoflavone | [22] | |

| V. heteroptera | Linhares Forest Reserve, Rio Doce, Espírito Santo—Brazil | Trunk wood | Maceration extraction; Solvent: benzene | Chrysophanol, sitosterol, stigmasterol, emodin, (2S)-7-hydroxiflavone, and formononetin | [31] |

| V. macrocarpa | Campo Grande, Mato Grosso—Brazil | Leaves | Maceration extraction; Solvent: ethanol | Catechin, epicatechin, kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside, tannins | [24] |

| Experimental Model | Specie | Extract (Part) | Dose/Concentration (via) | Key Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Studies | |||||

| In vitro toxicity | |||||

| Leukocyte viability (mice) | V. macrocarpa | Ethanolic (leaves) | 3–90 μg/mL | No cytotoxicity (MTT). | [24] |

| Lymphocyte culture (human) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 0.5–45 µM | Trypan blue assay—concentration-dependent cytotoxicity (≥1 µM) | [43] |

| 0.5–8 µM | Comet assay: 8 µM—increases DNA damage 0.5–2 µM—decreases doxorubicin-induced DNA damage | ||||

| In vivo toxicity | |||||

| Acute (male mice) | V. guianensis | Hydroethanolic (seed) | 2000 and 5000 mg/kg (oral) | No signals of toxicity, or death. LD50 > 5000 mg/kg | [16] |

| V. macrocarpa | Methanolic (heartwood) | 100–5000 mg/kg (oral) | No behavioral changes, or death. LD50 > 5000 mg/kg | [44] | |

| Ethanolic (stembark) | 250–5000 mg/kg (oral) | No signals of toxicity, or death. LD50 > 5000 mg/kg | [26] | ||

| Subchronic 30 days (male rats) | V. macrocarpa | Methanolic (heartwood) | 20–500 mg/kg (oral) | No behavioral, anatomical, or histological changes, either death ↑ Segmented neutrophils (500 mg/kg). ↑ Alkaline phosphatase ↑ Plasma protein ↓ γ-glutamyl transferase (100 mg/kg). ↓ Triacylglyceride | [44] |

| Communicable diseases | |||||

| In vitro antibacterial test | |||||

| Enterococcus faecalis | V. guianensis | Hydroalcoholic (seed) Hexane (seed) Chloroform (seed) Methanolic (seed) | 0.4–100 μg/mL | MIC 12.5 μg/mL; MBC 25 μg/mL MIC 12.5 μg/mL; MBC 25 μg/mL MIC 3.12 μg/mL; MBC 12.5 μg/mL MIC 12.5 μg/mL; MBC 50 μg/mL | [45] |

| Escherichia coli | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 1.0–1024 μg/mL | No antibiotic activity (MIC ≥ 1024 μg/mL) Decrease norfloxacin antibiotic activity | [42] |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 31.25–250 μg/mL | No antibiotic activity (MIC > 250 μg/mL) | [40] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 31.25–250 μg/mL | Weakly inhibition of planktonic growth (250 μg/mL). | [40] |

| V. guianensis | Hydroalcoholic (seed) Hexane (seed) Chloroform (seed) Methanolic (seed) | 0.4–100 μg/mL | MIC 25 μg/mL; MBC 100 μg/mL MIC 25 μg/mL; MBC 100 μg/mL MIC 25 μg/mL; MBC 100 μg/mL MIC 25 μg/mL; MBC 50 μg/mL | [45] | |

| Salmonella sp. | V. guianensis | Hydroalcoholic (seed) Hexane (seed) Chloroform (seed) Methanolic (seed) | 0.4–100 μg/mL | No activity No activity MIC 50 μg/mL; MBC 100 μg/mL MIC 50 μg/mL; MBC 100 μg/mL | [45] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | V. guianensis | Aqueous (leaves) | 2.275 mg/mL (30 μL/hole) | Antibacterial activity at 44.4% of ciprofloxacin (agar diffusion test). | [17] |

| Hydroalcoholic (seed) Hexane (seed) Chloroform (seed) Methanolic (seed) | 0.4–100 μg/mL | MIC 3.12 μg/mL; MBC 6.25 μg/mL MIC 6.25 μg/mL; MBC 12.5 μg/mL MIC 3.12 μg/mL; MBC 12.5 μg/mL MIC 6.25 μg/mL; MBC 12.5 μg/mL | [45] | ||

| V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 1.0–1024 μg/mL | No antibiotic activity (MIC ≥ 1024 μg/mL) Increase in norfloxacin, penicillin, and gentamicin antibiotic activity | [42] | |

| V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 31.25–250 μg/mL | Complete inhibition of planktonic growth (250 μg/mL) Inhibition of biomass formation in biofilms Decrease in the number of viable cells in the biofilm | [40] | |

| S. epidermidis | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 31.25–250 μg/mL | Complete inhibition of planktonic growth (250 μg/mL) Influence in biofilm formation Decrease in the number of viable cells in the biofilm | [40] |

| Streptococcus sanguis | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 100 μg/mL | Inhibition of bacterial adhesion to the acquired pellicle on tooth enamel | [41] |

| In vivo antibacterial test | |||||

| Mycobacterium bovis | V. macrocarpa | Ethanolic (leaves) | 30–300 mg/kg | Antimycobacterial activity | [24] |

| In vitro antifungal test | |||||

| Candida albicans | V. macrocarpa | Ethyl acetate (root bark) Vatacarpan (root bark) | - | MIC 0.98 µg/mL MIC 0.98 µg/mL | [20] |

| Lectin (seed) | 31.25–250 µg/mL | Weakly inhibition of planktonic growth (250 µg/mL) | [40] | ||

| V. guianensis | Ethanolic extract (leaves) Hexanic fraction Ethyl acetate fraction Methanol/H2O fraction | 0.125–1024 µg/mL | MIC 128 µg/mL; MFC 512 µg/mL No activity MIC 16 µg/mL; MFC 32 µg/mL. No activity | [22] | |

| 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxy-8-prenylisoflavone | 0.125–256 µg/mL | No activity | |||

| C. dubliniensis | V. guianensis | Ethanolic extract (leaves) Hexanic fraction Ethyl acetate fraction Methanol/H2O fraction | 0.125–1024 µg/mL | MIC 32 µg/mL MIC 64 µg/mL MIC 8 µg/mL; MFC 16 µg/mL No activity | [22] |

| 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxy-8-prenylisoflavone | 0.125–256 µg/mL | MIC 8 µg/mL | |||

| C. krusei | V. guianensis | Ethanolic extract (leaves) Hexanic fraction Ethyl acetate fraction Methanol/H2O fraction | 0.125–1024 µg/mL | MIC 128 µg/mL MIC 512 µg/mL; MFC 512 µg/mL MIC 8 µg/mL; MFC 32 µg/mL No activity | [22] |

| 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxy-8-prenylisoflavone | 0.125–256 µg/mL | No activity | |||

| C. parapsilosis | V. macrocarpa | Ethyl acetate | - | MIC 0.98 µg/mL | [20] |

| V. guianensis | Ethanolic extract (leaves) Hexanic fraction Ethyl acetate fraction Methanol/H2O fraction | No activity MIC 64 µg/mL MIC 8 µg/mL; MFC 32 µg/mL No activity | [22] | ||

| 5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxy-8-prenylisoflavone | 0.125–256 µg/mL | MIC 32 µg/mL | |||

| In vitro antiprotozoal test | |||||

| Leishmania amazonensis | V. macrocarpa | Ethyl acetate (root bark) | - | Antileishmanial activity (IC50 71.47 µg/mL) | [20] |

| Non-communicable diseases | |||||

| Endocrine system | |||||

| Type 2 diabetes (streptozotocin; male rats) | V. macrocarpa | Ethanolic (stembark) | 250 and 500 mg/kg (oral, 22 days) | Reductions observed include postprandial glycemia, food and fluid intake, urinary volume, and the excretion of glucose and urea in urine Improvement in weight gain Reduction in HOMA-R index | [26] |

| 500 mg/kg (oral, 21 days) | Increase insulin receptor and AKT phosphorylation in the liver, extensor digitorum longus muscles, and retroperitoneal white adipose tissue | [27] | |||

| Cardiovascular and renal systems | |||||

| Ex vivo aortic contraction (rat) | V. guianensis | Lectin (seed) | 1–100 μg/mL | Concentration-dependent relaxation of phenylephrine-induced aortic contraction This effect appears to involve the release of nitric oxide (NO) by the vascular endothelium Galactose abolishes the lectin’s vasorelaxant effect | [38] |

| In situ kidney perfusion (rat) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 10 μg/mL | Increase perfusion pressure, renal vascular resistance, urinary flow, and glomerular filtration rate Galactose abolishes the lectin’s kidney effect Moderate protein buildup in tubules and urinary spaces Renal tubules with eosinophilic casts | [46] |

| Angiogenic activity Embryo chorioallantoic membrane (chicken) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 0.5–8 μM | ↑ Vascularization and number of blood vessels (angiogenesis) ↑ Length, size, number of complexes, and blood vessel junctions ↑ Inflammatory cells and fibroblasts ↑ Thickening of CAM ↑ VEGF and TNF-α expression Lactose reduced the lectin’s effects | [43] |

| Immune system | |||||

| In vitro inflammation | |||||

| Neutrophil phagocytic activity | V. macrocarpa | Ethanolic (leaves) | 3–30 μg/mL | Reduction in neutrophil phagocytic activity | [24] |

| In vivo inflammation | |||||

| Carrageenan-induced pleurisy, BCG-induced pleurisy, CFA-induced paw edema | V. macrocarpa | Ethanolic (leaves) | 10–300 mg/kg (oral) | Dose-dependent reduction in leukocyte migration and protein concentration in pleural exudate CFA-induced paw edema: no effect in hyperalgesia, reduction in paw edema, and cold sensitivity | [24] |

| Neutrophil migration (female rat) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 9.6 × 10−7, 1.9 × 10−6, or 3.8 × 10−6 M (1 mL, intraperitoneal) | Neutrophil and mononuclear cell migration to the peritoneal cavity is induced in a dose-dependent manner through macrophage-mediated mechanisms (cytokine release) Galactose abolishes the lectin’s proinflammatory effect, suggesting it acts via its carbohydrate-binding site. | [47] |

| V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 4.8 × 10−7, 9.6 × 10−7, or 1.9 × 10−6 mol | Lectin induces cultured macrophages to release a neutrophil chemotactic mediator | [48] | |

| Paw edema (rat) | V. guianensis | Lectin (seed) | 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mg/kg | Time- and dose-dependent paw edema, with polymorphonuclear infiltrate Indomethacin (COX blocker) partially inhibits this effect, but L-NAME (NOS inhibitor) does not | [49] |

| Central nervous system | |||||

| Neuroinflammation (male mice) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 0.3–3 μg/site (intracerebroventricular) | Depressive-like effect (forced swimming test) Proinflammatory effect in the hippocampus: (↑ COX-2, GFAP, and S100B) | [50] |

| Nociception | |||||

| Orofacial nociception (zebrafish) | V. macrocarpa | Lectin (seed) | 0.025, 0.05 or 0.1 mg/mL (20 μL; intraperitoneal) | No pain relief effect | [51] |

| Wound-healing | |||||

| Dorsal wound (rat) | V. guianensis | Hydroethanolic (seed) | 100–500 mg/kg (topical) | Improve wound contraction from the third day of treatment (100 mg/kg) Inflammatory response reduction Stimulation of collagen synthesis | [16] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toledo, S.A.; Reis, L.D.d.S.; da Conceição, B.C.; Pantoja, L.V.P.d.S.; de Souza-Junior, F.J.C.; Garcez, F.C.S.; Maia, C.S.F.; Fontes-Junior, E.A. Vatairea Genus as a Potential Therapeutic Agent—A Comprehensive Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030422

Toledo SA, Reis LDdS, da Conceição BC, Pantoja LVPdS, de Souza-Junior FJC, Garcez FCS, Maia CSF, Fontes-Junior EA. Vatairea Genus as a Potential Therapeutic Agent—A Comprehensive Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(3):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030422

Chicago/Turabian StyleToledo, Sarah Andrade, Laryssa Danielle da Silva Reis, Brenda Costa da Conceição, Lucas Villar Pedrosa da Silva Pantoja, Fábio José Coelho de Souza-Junior, Flávia Cristina Santos Garcez, Cristiane Socorro Ferraz Maia, and Eneas Andrade Fontes-Junior. 2025. "Vatairea Genus as a Potential Therapeutic Agent—A Comprehensive Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 3: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030422

APA StyleToledo, S. A., Reis, L. D. d. S., da Conceição, B. C., Pantoja, L. V. P. d. S., de Souza-Junior, F. J. C., Garcez, F. C. S., Maia, C. S. F., & Fontes-Junior, E. A. (2025). Vatairea Genus as a Potential Therapeutic Agent—A Comprehensive Review of Ethnobotanical, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals, 18(3), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030422