Investigating the Role of Glycolysis in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule-Promoted Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Bioinformatics Analysis of Peripheral Artery Disease

2.1.1. Targets Associated with Peripheral Artery Disease

2.1.2. Gene Functional Enrichment Analysis of PAD-Associated Targets

2.2. Network Pharmacology Analysis

2.2.1. Active Compounds in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule and Target Prediction

2.2.2. Drug-Compound-Target Network Construction and Analysis

2.2.3. GO Functional and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Drug-Disease Intersection Targets

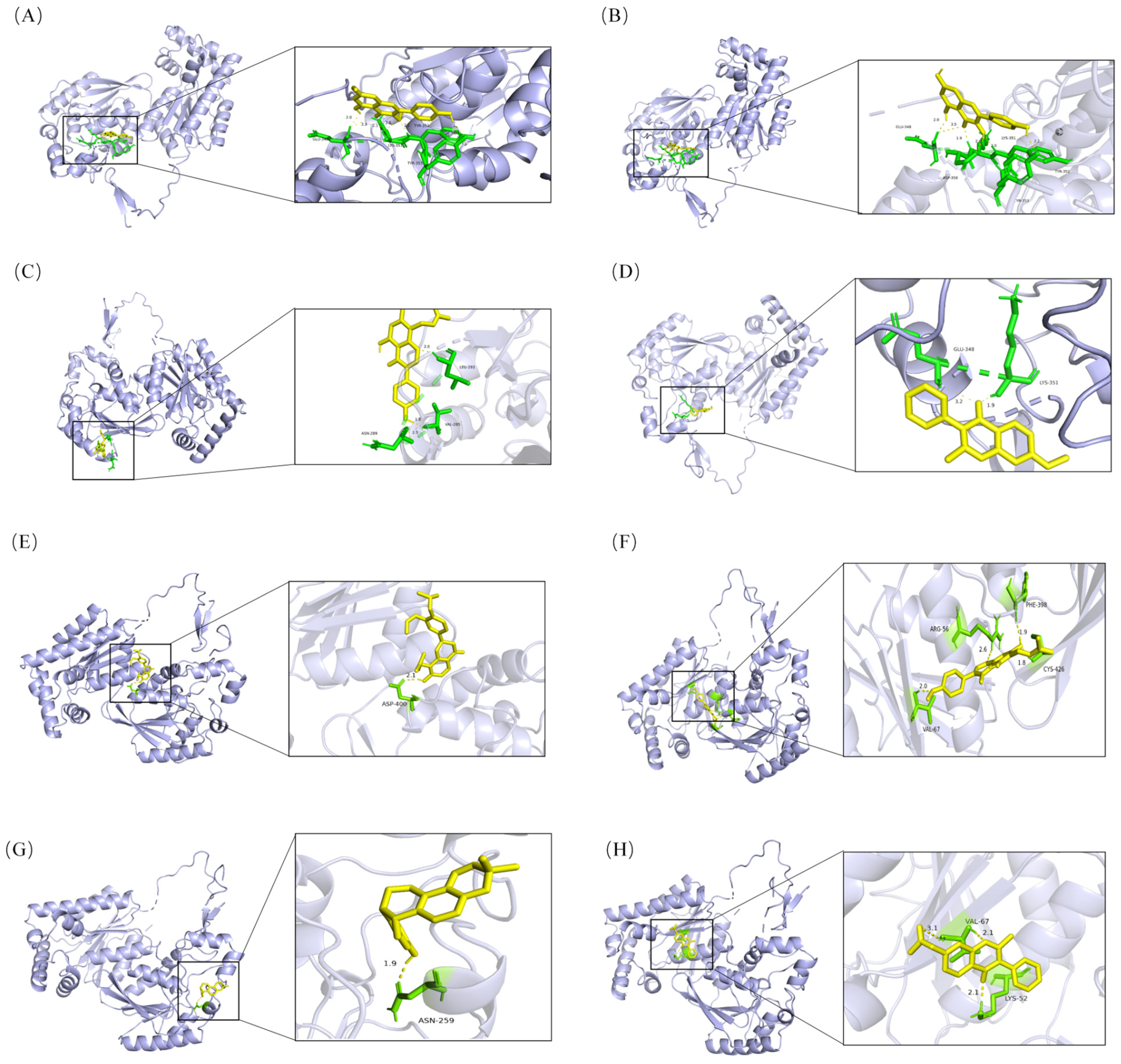

2.3. Molecular Docking

2.4. Effects of XFZYC-Containing Serum on In Vitro Tube Formation Ability and HIF-1α, HK2, and PFKFB3 Protein Expression in Endothelial Cells

2.5. Effects of XFZYC-Containing Serum and the Glycolytic Inhibitor 3PO on Endothelial Cell Angiogenic Behavior

2.6. Effects of XFZYC-Containing Serum and the Glycolytic Inhibitor 3PO on Glycolysis in Endothelial Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Cells

4.2. Medicine

4.3. Reagents

4.4. Screening of Active Drug Components and Action Targets

4.5. Acquisition of Peripheral Artery Disease-Related Targets

4.6. Enrichment Analysis

4.7. Molecular Docking Validation

4.8. Preparation of Drug-Containing Serum and Blank Serum

4.9. Cell Culture

4.10. Cell Behavior Analysis

4.10.1. In Vitro Tube Formation Assay

4.10.2. CCK-8 Assay

4.10.3. Scratch Wound Healing Assay

4.10.4. Transwell Assay

4.10.5. Cell Adhesion Assay

4.11. Colorimetric Assay for Glycolysis-Related Metabolite Levels and Key Enzyme Activities

4.12. Western Blot Analysis of PFKFB3, HK2, and HIF-1α Protein Levels

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3PO | 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (a glycolytic inhibitor) |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid |

| BP | Biological Process |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| EC | Endothelial Cell |

| ECL | Enhanced Chemiluminescence |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HEMC-1 | Human Microvascular Endothelial Cell line-1 |

| HERB | A high-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database of traditional Chinese medicine |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha |

| HK | Hexokinase |

| HK2 | Hexokinase 2 |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KLF2 | Krüppel-like Factor 2 |

| LA | Lactic Acid |

| MF | Molecular Function |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| OB | Oral Bioavailability |

| PAD | Peripheral Artery Disease |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PC | Pyruvate Carboxylase |

| PFK | Phosphofructokinase |

| PFKFB3 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/Fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 |

| PK | Pyruvate Kinase |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate Kinase Isoenzyme M2 |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Difluoride |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System |

| SPF | Specific Pathogen-Free |

| TBST | Tris-Buffered Saline with Tween |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid |

| TCMSP | Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| XFZYC | Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule |

Appendix A

| Mol ID/Name | Binding Protein | Binding Energy (kcal∙mol−1) |

|---|---|---|

| MOL000422 | PFKFB3 | −6.95 |

| MOL004598 | PFKFB3 | −5.63 |

| MOL000239 | PFKFB3 | −6.99 |

| MOL000392 | PFKFB3 | −5.98 |

| MOL000417 | PFKFB3 | −5.84 |

| MOL000422 | PFKFB3 | −6.68 |

| MOL003656 | PFKFB3 | −6.68 |

| MOL003896 | PFKFB3 | −6.76 |

| MOL004806 | PFKFB3 | −6.14 |

| MOL004814 | PFKFB3 | −5.45 |

| MOL004828 | PFKFB3 | −5.72 |

| MOL004835 | PFKFB3 | −7.15 |

| MOL004856 | PFKFB3 | −6.38 |

| MOL004857 | PFKFB3 | −6.29 |

| MOL004863 | PFKFB3 | −5.72 |

| MOL004866 | PFKFB3 | −7.22 |

| MOL004891 | PFKFB3 | −6.34 |

| MOL004908 | PFKFB3 | −5.8 |

| MOL004915 | PFKFB3 | −6.2 |

| MOL004949 | PFKFB3 | −6.29 |

| MOL004957 | PFKFB3 | −5.66 |

| MOL004990 | PFKFB3 | −7.36 |

| MOL004991 | PFKFB3 | −5.9 |

| MOL005007 | PFKFB3 | −5.96 |

| MOL005016 | PFKFB3 | −5.49 |

| MOL000006 | PFKFB3 | −4.73 |

| MOL002695 | PFKFB3 | −5.29 |

| MOL002712 | PFKFB3 | −5.96 |

| MOL002714 | PFKFB3 | −5.55 |

| MOL002717 | PFKFB3 | −3.49 |

| MOL002151 | PFKFB3 | −5.14 |

| MOL000173 | PFKFB3 | −4.1 |

| MOL001002 | PFKFB3 | −4.39 |

| MOL000785 | PFKFB3 | −1.98 |

| MOL004702 | HIF-1α | −5.03 |

| MOL004820 | HIF-1α | −5.39 |

| MOL006992 | HIF-1α | −3.35 |

| MOL005008 | HIF-1α | −5.5 |

| MOL004824 | HIF-1α | −2.17 |

| Rehmaglutin C | HK2 | −6.95 |

References

- Hussain, M.A.; Al-Omran, M.; Creager, M.A.; Anand, S.S.; Verma, S.; Bhatt, D.L. Antithrombotic Therapy for Peripheral Artery Disease: Recent Advances. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2450–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboyans, V.; Canonico, M.E.; Chastaingt, L.; Anand, S.S.; Brodmann, M.; Couffinhal, T.; Criqui, M.H.; Debus, E.S.; Mazzolai, L.; McDermott, M.M.; et al. Peripheral artery disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, A.; Menard, M.T.; Conte, M.S.; Kaufman, J.A.; Powell, R.J.; Choudhry, N.K.; Hamza, T.H.; Assmann, S.F.; Creager, M.A.; Cziraky, M.J.; et al. Surgery or Endovascular Therapy for Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, A.C.; Griffioen, A.W. Pathological angiogenesis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 313–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelen, G.; Treps, L.; Li, X.; Carmeliet, P. Basic and Therapeutic Aspects of Angiogenesis Updated. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Sun, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Wei, F. PFKFB3 in neovascular eye disease: Unraveling mechanisms and exploring therapeutic strategies. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, D.; Lin, F. Glycometabolic Regulation of Angiogenesis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, K.M.; Chaube, B.; Fernández-Hernando, C.; Suárez, Y. Intracellular endothelial cell metabolism in vascular function and dysfunction. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 36, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annex, B.H.; Cooke, J.P. New Directions in Therapeutic Angiogenesis and Arteriogenesis in Peripheral Arterial Disease. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1944–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; He, C.; Bi, Y.; Zhu, X.; Deng, D.; Ran, T.; Ji, X. Synergistic effect of VEGF and SDF-1α in endothelial progenitor cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 914347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Sun, W.; Fang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C. Clinical features, treatment, and outcomes of patients with carfilzomib induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 134, 112178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; He, F.; Hu, Z.; He, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Xiang, J.; Li, J.; He, B.; et al. Analysis of Potential Mechanism of Herbal Formula Taohong Siwu Decoction against Vascular Dementia Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 1235552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Tang, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, W.; Tan, S.; He, B. Potential and applications of capillary electrophoresis for analyzing traditional Chinese medicine: A critical review. Analyst 2021, 146, 4724–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xie, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, W.; Lei, J. Isoorientin Ameliorates Macrophage Pyroptosis and Atherogenesis by Reducing KDM4A Levels and Promoting SKP1-Cullin1-F-box E3 Ligase-mediated NLRP3 Ubiquitination. Inflammation 2025, 48, 3629–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, J.; Rotili, D.; Mai, A.; Steegborn, C.; Xu, S.; Jin, Z.G. SIRT6 Protects Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation in Human Pulmonary Lung Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Inflammation 2024, 47, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, R.; Kuruburu, M.G.; Leihang, Z.; Bovilla, V.R.; Rajashetty, R.; Madhusetty, R.C.; Vaagesh, V.Y.; Madhunapantula, S.V. Variations in the fetal bovine serum and glucose concentration in the culture medium impact the viability of glioblastoma cells as evidenced through the modulation of cell cycle and reactive oxygen species: An in vitro study. J. Biol. Methods 2025, 12, e99010071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Yang, J.; Ye, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chai, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y. Bioactive components and mechanisms of the traditional Chinese herbal formula Xuefu Zhuyu formula in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 348, 119873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Nie, S.; Yi, M.; Wu, N.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Wang, D. UPLC-QTOF/MS-based metabolomics analysis of plasma reveals an effect of Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu capsules on blood-stasis syndrome in CHD rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 241, 111908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Qiu, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, D. (1)H NMR-based metabolomics study of the dynamic effect of Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu capsules on coronary heart disease rats induced by high-fat diet, coronary artery ligation. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 195, 113869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.L.; Tang, Y.P.; Duan, J.L.; Yao, K.W. Efficacy and Safety of Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu Decoction for Patients with Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9931826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, X.; Lu, Z.; Han, X.; Zhao, M. Effectiveness and safety of Xuefu Zhuyu decoction for treating coronary heart disease angina: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e14708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.L.; Lu, P.F.; Gao, D.; Song, J.; Chen, K.J. Effect of Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule on Angiogenesis in Hindlimb Ischemic Rats. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yizheng, W.; Xiaoling, X.; Ruyu, L.; Xiaohui, L.; Yu, C. Effect of Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule on the expression of Dll4 in human microvascular endothelial cells. J. Li Shizhen Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 29, 1311–1313. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yizheng, W.; Fan, L.; Fei, C.; Yaqiong, H.; Dong, G. Mechanism of Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule in Regulating Angiogenesis via the Jagged1/Notch Signaling Pathway. Chin. J. Exp. Tradit. Med. Formulae 2017, 23, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.E.; Yamaguchi, D.J.; Schmidt, C.A.; Zeczycki, T.N.; Shaikh, S.R.; Brophy, P.; Green, T.D.; Tarpey, M.D.; Karnekar, R.; Goldberg, E.J.; et al. Extensive skeletal muscle cell mitochondriopathy distinguishes critical limb ischemia patients from claudicants. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e123235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, K.; Georgiadou, M.; Schoors, S.; Kuchnio, A.; Wong, B.W.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Quaegebeur, A.; Ghesquière, B.; Cauwenberghs, S.; Eelen, G.; et al. Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 2013, 154, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liang, X.; Gao, Y.; Fu, G.; Shen, Q. Hexokinase2 controls angiogenesis in melanoma by promoting aerobic glycolysis and activating the p38-MAPK signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 19721–19729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Guan, S.; Zhang, P.; Chen, D.; Luo, T. Deficiency of Microglial Hv1 Protects Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation via the NF-κB Signaling Pathway and HIF1α-Mediated Metabolic Reprogramming. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liang, S. HIF-1α depletion regulates autophagy to improve arteriosclerosis obliterans of the lower extremities via the TSP-1/CD47 axis. Life Sci. 2025, 378, 123817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqiong, H.; Jingsi, Z.; Fan, L.; Yizheng, W.; Dong, G.; Jun, S. Experimental Study on the Effect of Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule in Promoting Moderate Angiogenesis via Regulating EphB4/EphrinB2. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 2017, 37, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yizheng, W.; He, W.; Fei, C.; Fan, L.; Dong, G. Effect of Drug-Containing Serum from Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule on KLF2 Expression in Human Microvascular Endothelial Cells. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 62, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chi, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yin, S.; Qiu, Q. Identification of Bioactive Ingredients and Mechanistic Pathways of Xuefu Zhuyu Decoction in Ventricular Remodeling: A Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2025, 32, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, M.; Hu, E.; Yan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Luo, W.; Su, H.; Yu, Z.; Guo, X.; et al. Metabolomics integrated with network pharmacology of blood-entry constituents reveals the bioactive component of Xuefu Zhuyu decoction and its angiogenic effects in treating traumatic brain injury. Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Zeng, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Liao, D.; Li, R.; He, S.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; et al. A feedback loop driven by H3K9 lactylation and HDAC2 in endothelial cells regulates VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlenova, K.; Veys, K.; Miranda-Santos, I.; De Bock, K.; Carmeliet, P. Endothelial Cell Metabolism in Health and Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiyesimi, O.; Kuppuswamy, S.; Zhang, G.; Batan, S.; Zhi, W.; Ganta, V.C. Glycolytic PFKFB3 and Glycogenic UGP2 Axis Regulates Perfusion Recovery in Experimental Hind Limb Ischemia. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1764–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Xia, Y. Metabolic reprogramming and interventions in angiogenesis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 70, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Antognazza, M.R.; Lodola, F. Towards Novel Geneless Approaches for Therapeutic Angiogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 616189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelen, G.; de Zeeuw, P.; Treps, L.; Harjes, U.; Wong, B.W.; Carmeliet, P. Endothelial Cell Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 3–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Yuan, J.; Nan, Y.; Liu, J. Endothelial GABBR2 Regulates Post-ischemic Angiogenesis by Inhibiting the Glycolysis Pathway. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 696578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Patysheva, M.; Iamshchikov, P.; Kazakova, E.; Kazakova, A.; Rakina, M.; Grigoryeva, E.; Tarasova, A.; Afanasiev, S.; Bezgodova, N.; et al. PFKFB3 overexpression in monocytes of patients with colon but not rectal cancer programs pro-tumor macrophages and is indicative for higher risk of tumor relapse. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, J.A.; Dvorak, A.M.; Dvorak, H.F. VEGF-A and the induction of pathological angiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2007, 2, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Meng, L.; Huang, J. Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) improve symptoms of post-ischemic stroke depression by activating VEGF to mediate the MAPK/ERK pathway. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoors, S.; De Bock, K.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Georgiadou, M.; Ghesquière, B.; Cauwenberghs, S.; Kuchnio, A.; Wong, B.W.; Quaegebeur, A.; Goveia, J.; et al. Partial and transient reduction of glycolysis by PFKFB3 blockade reduces pathological angiogenesis. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, B.; Huang, C.; Li, P.; Guo, Z.; Tao, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Bu, D.; Liu, X.; Huo, P.; Cao, W.; et al. HERB: A high-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database of traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1197–D1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New Docking Methods, Expanded Force Field, and Python Bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; He, X.; Shu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G. Integrating serum pharmacochemistry, network pharmacology, and metabolomics to explore the protective mechanism of Hua-Feng-Dan in ischemic stroke. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Herb Name | Number of Active Components | Number of Predicted Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Chaihu | 13 | 374 |

| Chishao | 15 | 195 |

| Chuanxiong | 4 | 253 |

| Danggui | 2 | 44 |

| Gancao | 86 | 775 |

| Honghua | 11 | 343 |

| Jiegeng | 2 | 101 |

| Niuxi | 8 | 408 |

| Shengdihuang 1 | 3 | 55 |

| Taoren | 19 | 251 |

| Zhiqiao | 4 | 168 |

| Total | 167 | 2967 |

| Mol ID | Name | Herbal Sources | Binding Energy (kcal∙mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOL000422 | Kaempferol | Caihu, Honghua, Niuxi, Gancao | −6.95 |

| MOL000239 | Jaranol | Gancao | −6.99 |

| MOL003656 | Lupiwighteone | Gancao | −6.68 |

| MOL003896 | 7-Methoxy-2-methyl isoflavone | Gancao | −6.68 |

| MOL004806 | Euchrenone | Gancao | −6.76 |

| MOL004856 | Gancaonin A | Gancao | −7.15 |

| MOL004891 | Shinpterocarpin | Gancao | −7.22 |

| MOL004991 | 7-Acetoxy-2-methylisoflavone | Gancao | −7.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, F.; Yao, Z.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Fu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, C.; et al. Investigating the Role of Glycolysis in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule-Promoted Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Validation. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121902

Lin F, Yao Z, Yu J, Chen X, Chen X, Li Y, Fu J, Cheng Y, Li J, Fang C, et al. Investigating the Role of Glycolysis in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule-Promoted Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Validation. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121902

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Fan, Zhifeng Yao, Jiaming Yu, Xiaoqi Chen, Xinlei Chen, Yuxia Li, Juanli Fu, Ye Cheng, Junting Li, Chang Fang, and et al. 2025. "Investigating the Role of Glycolysis in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule-Promoted Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Validation" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121902

APA StyleLin, F., Yao, Z., Yu, J., Chen, X., Chen, X., Li, Y., Fu, J., Cheng, Y., Li, J., Fang, C., Wang, Y., Wang, H., & Cai, J. (2025). Investigating the Role of Glycolysis in Xuefu Zhuyu Capsule-Promoted Angiogenesis in Endothelial Cells: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Validation. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1902. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121902