Pridopidine, a Potent and Selective Therapeutic Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Agonist for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases

Abstract

1. The Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R)

2. Neurodegenerative Diseases

3. Pridopidine

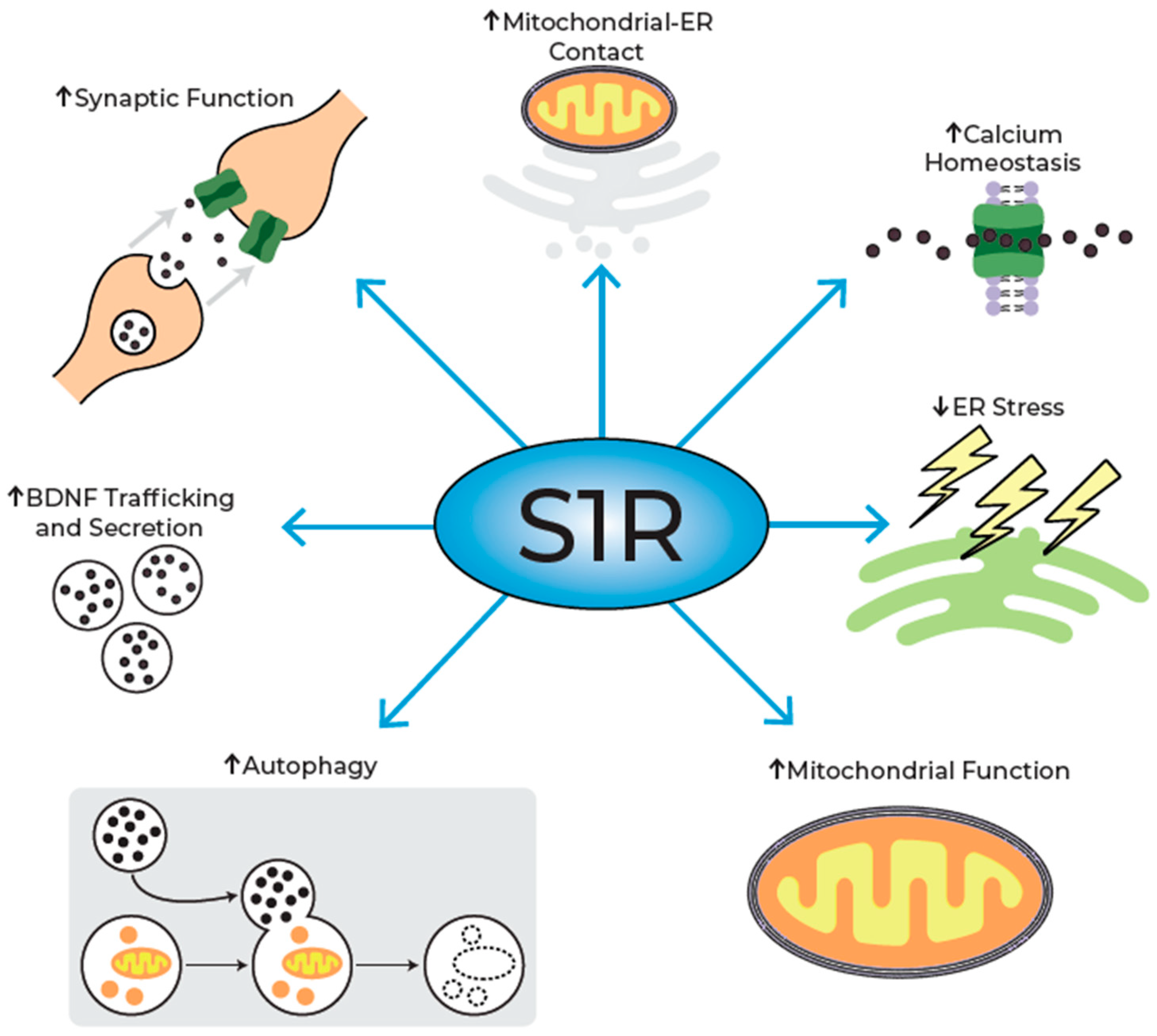

4. Mechanism of Action of Pridopidine

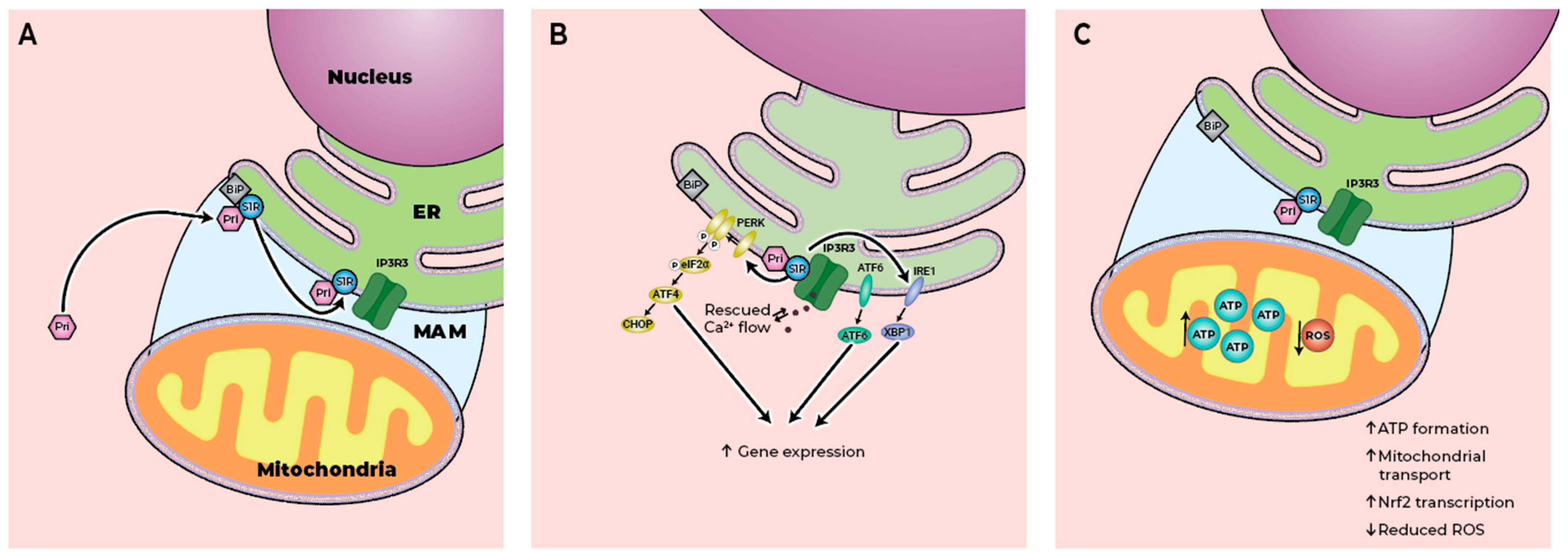

4.1. Preservation of MAM Integrity

4.2. Regulation of ER Stress

4.3. Modulation of Mitochondrial Function

4.4. Autophagy Enhancement

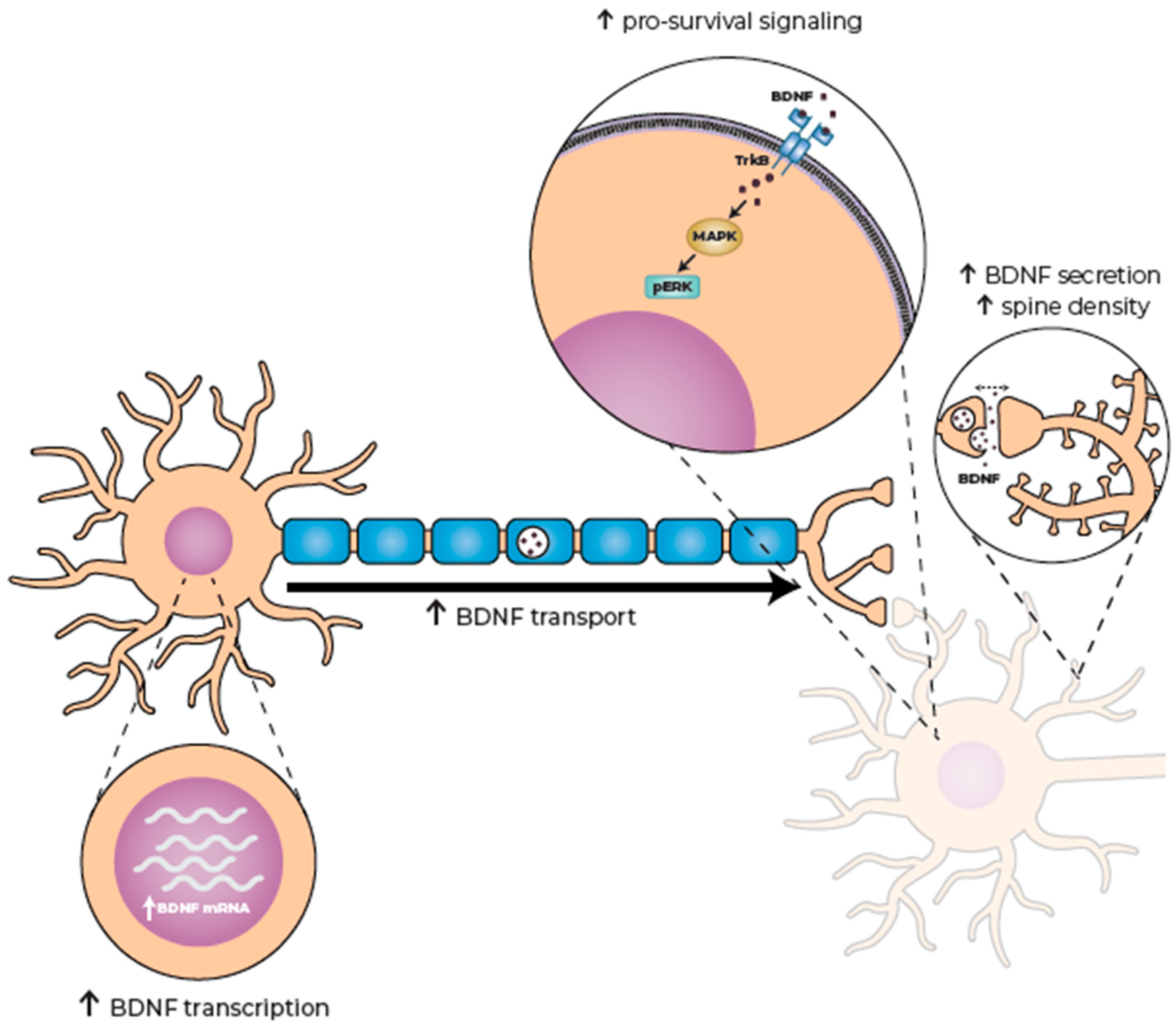

4.5. Increasing Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Availability

4.6. Preservation of Dendritic Spine Density

4.7. Restoration of Neuromuscular Junction Activity

4.8. Enhancement of Neuroprotection

5. The Biphasic Effect of S1R Activation

6. Beneficial Effects of Pridopidine in Models of Neurodegenerative Diseases

7. Clinical Evidence

7.1. Pridopidine Efficacy in HD

7.2. Pridopidine Efficacy in ALS

7.3. Safety

8. Potential Future Therapeutic Avenues

8.1. Parkinson’s Disease

8.2. Alzheimer’s Disease

8.3. Retinal Degeneration

8.4. Neurodevelopmental Disorders

8.5. Vanishing White Matter (VWM) Disease

8.6. Wolfram Syndrome (WFS)

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maurice, T. Bi-phasic dose response in the preclinical and clinical developments of sigma-1 receptor ligands for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.C. Distinct Regulation of sigma (1) Receptor Multimerization by Its Agonists and Antagonists in Transfected Cells and Rat Liver Membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 373, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryskamp, D.A.; Korban, S.; Zhemkov, V.; Kraskovskaya, N.; Bezprozvanny, I. Neuronal Sigma-1 Receptors: Signaling Functions and Protective Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Bezprozvanny, I. Structure-Based Modeling of Sigma 1 Receptor Interactions with Ligands and Cholesterol and Implications for Its Biological Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, N.; Fang, X.; Gupta, N.; Nie, D. Pharmacological and Pathological Implications of Sigma-1 Receptor in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhemkov, V.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; Bezprozvanny, I. Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Interaction with Cholesterol: Mechanisms of S1R Activation and Its Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delprat, B.; Crouzier, L.; Su, T.P.; Maurice, T. At the Crossing of ER Stress and MAMs: A Key Role of Sigma-1 Receptor? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1131, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovinovic, A.; Greig, J.; Martin-Guerrero, S.M.; Salam, S.; Paillusson, S. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria signaling in neurons and neurodegenerative diseases. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs248534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, J. Mitochondria-associated membranes: A hub for neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 149, 112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyamurthy, V.H.; Nagarajan, Y.; Parvathi, V.D. Mitochondria-Endoplasmic Reticulum Contact Sites (MERCS): A New Axis in Neuronal Degeneration and Regeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 6528–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, R.; De Vos, K.J.; Paillusson, S.; Mueller, S.; Sancho, R.M.; Lau, K.F.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Lin, W.L.; Xu, Y.F.; Lewis, J.; et al. ER-mitochondria associations are regulated by the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and are disrupted by ALS/FTD-associated TDP-43. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, R.; Paillusson, S.; Gomez-Suaga, P.; Mitchell, J.C.; Lau, D.H.; Gray, E.H.; Sancho, R.M.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; De Vos, K.J.; Shaw, C.E.; et al. ALS/FTD-associated FUS activates GSK-3beta to disrupt the VAPB-PTPIP51 interaction and ER-mitochondria associations. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cali, T.; Ottolini, D.; Negro, A.; Brini, M. Enhanced parkin levels favor ER-mitochondria crosstalk and guarantee Ca2+ transfer to sustain cell bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, N.S.; Dentoni, G.; Schreiner, B.; Naia, L.; Piras, A.; Graff, C.; Cattaneo, A.; Meli, G.; Hamasaki, M.; Nilsson, P.; et al. Amyloid Beta-Peptide Increases Mitochondria-Endoplasmic Reticulum Contact Altering Mitochondrial Function and Autophagosome Formation in Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Models. Cells 2020, 9, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca2+ signaling and cell survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Maurice, T.; Su, T.P. Ca2+ signaling via sigma(1)-receptors: Novel regulatory mechanism affecting intracellular Ca2+ concentration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Hayashi, T.; Hayashi, E.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperone at the ER-mitochondrion interface mediates the mitochondrion-ER-nucleus signaling for cellular survival. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.S.; Gorki, V.; Bhardwaj, R.; Punnakkal, P. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: Implications in Diseases. Protein J. 2025, 44, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhemkov, V.; Ditlev, J.A.; Lee, W.R.; Wilson, M.; Liou, J.; Rosen, M.K.; Bezprozvanny, I. The role of sigma 1 receptor in organization of endoplasmic reticulum signaling microdomains. Elife 2021, 10, e65192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T. The Sigma-1 Receptor in Cellular Stress Signaling. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariesen, A.D.; Tuomainen, R.E.; De Deyn, P.P.; Tucha, O.; Koerts, J. Let Us Talk Money: Subjectively Reported Financial Performance of People Living with Neurodegenerative Diseases-A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2024, 34, 668–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruge, A.; Ponimaskin, E.; Labus, J. Targeting the serotonergic system in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases-emerging therapies and unmet challenges. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wareham, L.K.; Liddelow, S.A.; Temple, S.; Benowitz, L.I.; Di Polo, A.; Wellington, C.; Goldberg, J.L.; He, Z.; Duan, X.; Bu, G.; et al. Solving neurodegeneration: Common mechanisms and strategies for new treatments. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugger, B.N.; Dickson, D.W. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Basic mechanisms of neurodegeneration: A critical update. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, R.K.; Gupta, T.; Kumar, V.; Rani, S.; Gupta, U. Aetiology and pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders. In Nanomedical Drug Delivery for Neurodegenerative Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J.; Alugoju, P.; Anthikapalli, N.V.A.; Jayaraman, S.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Gopathy, S.; Roy, J.R.; Janaki, C.S.; Thalamati, D.; et al. New strategies of neurodegenerative disease treatment with extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Theranostics 2023, 13, 4138–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Saura, G.; Bernardi, E.; Bojtos, L.; Martinez-Horta, S.; Pagonabarraga, J.; Kulisevsky, J.; Perez-Perez, J. Update on the Symptomatic Treatment of Huntington’s Disease: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, N.; Fruzzetti, F.; Farinazzo, G.; Candiani, G.; Marcuzzo, S. Perspectives in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Biomarkers, Omics, and Gene Therapy Informing Disease and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Sanchez, M.; Licitra, F.; Underwood, B.R.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Huntington’s Disease: Mechanisms of Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a024240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Yang, T.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Zhou, G.; Yang, S.; Yin, S.; Li, X.J.; Li, S. Huntington’s Disease: Complex Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubkova, A.E.; Yudkin, D.V. Regulation of HTT mRNA Biogenesis: The Norm and Pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Ghosh, R.; Leavitt, B.R. Huntingtin Lowering Strategies for Disease Modification in Huntington’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 102, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccato, C.; Cattaneo, E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2009, 5, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforet, G.A.; Sapp, E.; Chase, K.; McIntyre, C.; Boyce, F.M.; Campbell, M.; Cadigan, B.A.; Warzecki, L.; Tagle, D.A.; Reddy, P.H.; et al. Changes in cortical and striatal neurons predict behavioral and electrophysiological abnormalities in a transgenic murine model of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 9112–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roze, E.; Cahill, E.; Martin, E.; Bonnet, C.; Vanhoutte, P.; Betuing, S.; Caboche, J. Huntington’s Disease and Striatal Signaling. Front. Neuroanat. 2011, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, S.; Decker, L.; Freischmidt, A. Genetics of ALS—Genes and modifier. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2025, 38, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolochko, C.; Shiryaeva, O.; Alekseeva, T.; Dyachuk, V. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies (Part 2). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, K.; Belanger, S.M.; Lachance, V.; Kourrich, S. Repurposing Sigma-1 Receptor-Targeting Drugs for Therapeutic Advances in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando-Grabulosa, M.; Gaja-Capdevila, N.; Vela, J.M.; Navarro, X. Sigma 1 receptor as a therapeutic target for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 1336–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokr, M.M.; Badawi, G.A.; Elshazly, S.M.; Zaki, H.F.; Mohamed, A.F. Sigma 1 Receptor and Its Pivotal Role in Neurological Disorders. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aishwarya, R.; Abdullah, C.S.; Morshed, M.; Remex, N.S.; Bhuiyan, M.S. Sigmar1’s Molecular, Cellular, and Biological Functions in Regulating Cellular Pathophysiology. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 705575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Ilieva, H.; Tamada, H.; Nomura, H.; Komine, O.; Endo, F.; Jin, S.; Mancias, P.; Kiyama, H.; Yamanaka, K. Mitochondria-associated membrane collapse is a common pathomechanism in SIGMAR1- and SOD1-linked ALS. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saif, A.; Al-Mohanna, F.; Bohlega, S. A mutation in sigma-1 receptor causes juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruszak, A.; Karlström, H.; Brooks, W.S.; Coupland, K.G.; Tchorzewska, J.; Schofield, P.R.; Dobson-Stone, C.; Blair, I.P.; Kwok, J.B.J.; Loy, C.T.; et al. Sigma nonopioid intracellular receptor 1 mutations cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration-motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, Y.; Morino, H.; Miyamoto, R.; Matsuda, Y.; Ohsawa, R.; Kurashige, T.; Shimatani, Y.; Kaji, R.; Kawakami, H. Compound heterozygote mutations in the SIGMAR1 gene in an oldest-old patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 1519–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kwon, M.J.; Choi, W.J.; Oh, K.W.; Oh, S.I.; Ki, C.S.; Kim, S.H. Mutations in UBQLN2 and SIGMAR1 genes are rare in Korean patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1957.e7–1957.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregianin, E.; Pallafacchina, G.; Zanin, S.; Crippa, V.; Rusmini, P.; Poletti, A.; Fang, M.; Li, Z.; Diano, L.; Petrucci, A.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the SIGMAR1 gene cause distal hereditary motor neuropathy by impairing ER-mitochondria tethering and Ca2+ signalling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 3741–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.Y.; Van Karnebeek, C.D.M.; Drö, B.; Shyr, C.; Tarailo-Graovac, M.; Eydoux, P.; Ross, C.J.; Wasserman, W.W.; Bjö, B.; Wu, J.K. Further Validation of the SIGMAR1 c.151þ1G>T Mutation as Cause of Distal Hereditary Motor Neuropathy. Child Neurol. Open 2016, 3, 2329048X16669912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zi, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Xia, K.; Tang, B.; et al. A SIGMAR1 splice-site mutation causes distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Neurology 2015, 84, 2430–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Nazar, R.B.M.; Chen, S.; Qian, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. A novel SIGMAR1 missense mutation leads to distal hereditary motor neuropathy phenotype mimicking juvenile ALS: A case report of China. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1477518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, S.; Ciscato, F.; Petrucci, A.; Botta, A.; Chiossi, F.; Vazza, G.; Rizzuto, R.; Pallafacchina, G. Mutated sigma-1R disrupts cell homeostasis in dHMN patient cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehér, A.; Juhász, A.; László, A.; Kálmán, J.; Pákáski, M.; Kálmán, J.; Janka, Z. Association between a variant of the sigma-1 receptor gene and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 517, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, N.; Ujike, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Sakai, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujisawa, Y.; Kanzaki, A.; Kuroda, S. A variant of the sigma receptor type-1 gene is a protective factor for Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 13, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishina, M.; Ohyama, M.; Ishii, K.; Kitamura, S.; Kimura, Y.; Oda, K.-I.; Kawamura, K.; Sasaki, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Katayama, Y.; et al. Low density of sigma1 receptors in early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Nucl. Med. 2008, 22, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-Y.A.; Chuang, J.-Y.; Tsai, M.-S.; Wang, X.-F.; Xi, Z.-X.; Hung, J.-J.; Chang, W.-C.; Bonci, A.; Su, T.-P. Sigma-1 receptor mediates cocaine-induced transcriptional regulation by recruiting chromatin-remodeling factors at the nuclear envelope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6562–E6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. Sigma-1 receptor knockout increases alpha-synuclein aggregation and phosphorylation with loss of dopaminergic neurons in substantia nigra. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 59, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Fontanilla, D.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Chae, Y.K.; Markley, J.L.; Ruoho, A.E. The sigma-1 receptor protects against cellular oxidative stress and activates antioxidant response elements. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 682, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlyutov, T.A.; Epstein, M.L.; Verbny, Y.I.; Huerta, M.S.; Zaitoun, I.; Ziskind-Conhaim, L.; Ruoho, A.E. Lack of sigma-1 receptor exacerbates ALS progression in mice. Neuroscience 2013, 240, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T.H.; Geva, M.; Steiner, L.; Orbach, A.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Savola, J.M.; Reynolds, I.J.; Ravenscroft, P.; Hill, M.; Fox, S.H.; et al. Pridopidine, a clinic-ready compound, reduces 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-induced dyskinesia in Parkinsonian macaques. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, S.; Grimmer, T.; Teo, K.; O’Brien, T.J.; Woodward, M.; Grunfeld, J.; Mander, A.; Brodtmann, A.; Brew, B.J.; Morris, P.; et al. Blarcamesine for the treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Results from the ANAVEX2-73-AD-004 Phase IIB/III trial. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 12, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malar, D.S.; Thitilertdecha, P.; Ruckvongacheep, K.S.; Brimson, S.; Tencomnao, T.; Brimson, J.M. Targeting Sigma Receptors for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 399–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Robson, M.J.; Healy, J.R.; Scandinaro, A.L.; Matsumoto, R.R. Involvement of sigma-1 receptors in the antidepressant-like effects of dextromethorphan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nochi, S.; Asakawa, N.; Sato, T. Kinetic study on the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-indanon)-2-yl]methylpiperidine hydrochloride (E2020). Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 18, 1145–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Costa, B.R.; Dominguez, C.; He, X.S.; Williams, W.; Radesca, L.; Bowen, W. Synthesis and biological evaluation of conformationally restricted 2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-N-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-N-methylethylenediam ines as sigma receptor ligands. 1. Pyrrolidine, piperidine, homopiperidine, and tetrahydroisoquinoline classes. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 4334–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Activation of sigma-1 receptor chaperone in the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases and its clinical implication. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 127, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peprah, K.; Zhu, X.Y.; Eyunni, S.V.; Setola, V.; Roth, B.L.; Ablordeppey, S.Y. Multi-receptor drug design: Haloperidol as a scaffold for the design and synthesis of atypical antipsychotic agents. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C.I.; Mustafa, E.R.; Cornejo, M.P.; Yaneff, A.; Rodriguez, S.S.; Perello, M.; Raingo, J. Chlorpromazine, an Inverse Agonist of D1R-Like, Differentially Targets Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel (Ca(V)) Subtypes in mPFC Neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 2644–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanba, S.; Suzuki, E.; Nomura, S.; Nakaki, T.; Yagi, G.; Asai, M.; Richelson, E. Affinity of neuroleptics for D1 receptor of human brain striatum. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1994, 19, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Grachev, I.D.; Meyer, P.M.; Becker, G.A.; Bronzel, M.; Marsteller, D.; Pastino, G.; Voges, O.; Rabinovich, L.; Knebel, H.; Zientek, F.; et al. Sigma-1 and dopamine D2/D3 receptor occupancy of pridopidine in healthy volunteers and patients with Huntington disease: A [18F] fluspidine and [18F] fallypride PET study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlholm, K.; Århem, P.; Fuxe, K.; Marcellino, D. The dopamine stabilizers ACR16 and (−)-OSU6162 display nanomolar affinities at the σ-1 receptor. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskamp, D.A.; Zhemkov, V.; Bezprozvanny, I. Mutational Analysis of Sigma-1 Receptor’s Role in Synaptic Stability. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddings, C.R.; Arbez, N.; Akimov, S.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; Ross, C.A. Pridopidine protects neurons from mutant-huntingtin toxicity via the sigma-1 receptor. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 129, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez-Silva, H.M.; Cuesto, G.; Romero, N.; Brito-Armas, J.M.; Acevedo-Arozena, A.; Acebes, A.; Marcellino, D.J. Pridopidine Promotes Synaptogenesis and Reduces Spatial Memory Deficits in the Alzheimer’s Disease APP/PS1 Mouse Model. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1566–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez-Silva, H.M.; Mediavilla, T.; Giacobbo, B.L.; Liu, X.; Sultan, F.R.; Marcellino, D.J. Pridopidine modifies disease phenotype in a SOD1 mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 1356–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francardo, V.; Geva, M.; Bez, F.; Denis, Q.; Steiner, L.; Hayden, M.R.; Cenci, M.A. Pridopidine Induces Functional Neurorestoration Via the Sigma-1 Receptor in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Miralles, M.; Geva, M.; Tan, J.Y.; Yusof, N.; Cha, Y.; Kusko, R.; Tan, L.J.; Xu, X.; Grossman, I.; Orbach, A.; et al. Early pridopidine treatment improves behavioral and transcriptional deficits in YAC128 Huntington disease mice. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e95665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, M.; Birnberg, T.; Weiner, B.; Lysaght, A.; Cha, Y.; Wagner, A.M.; Orbach, A.; Laufer, R.; Kusko, R.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Pridopidine activates neuroprotective pathways impaired in Huntington Disease. Human. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 3975–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.; Gradus, T.; Altman, T.; Maimon, R.; Avraham, N.S.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.; Perlson, E. Targeting the Sigma-1 Receptor via Pridopidine Ameliorates Central Features of ALS Pathology in a SOD1G93A Model. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusko, R.; Dreymann, J.; Ross, J.; Cha, Y.; Escalante-Chong, R.; Garcia-Miralles, M.; Tan, L.J.; Burczynski, M.E.; Zeskind, B.; Laifenfeld, D.; et al. Large-scale transcriptomic analysis reveals that pridopidine reverses aberrant gene expression and activates neuroprotective pathways in the YAC128 HD mouse. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naia, L.; Ly, P.; Mota, S.I.; Lopes, C.; Maranga, C.; Coelho, P.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Ankarcrona, M.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. The Sigma-1 Receptor Mediates Pridopidine Rescue of Mitochondrial Function in Huntington Disease Models. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskamp, D.; Wu, J.; Geva, M.; Kusko, R.; Grossman, I.; Hayden, M.; Bezprozvanny, I. The sigma-1 receptor mediates the beneficial effects of pridopidine in a mouse model of Huntington disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 97, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryskamp, D.; Wu, L.; Wu, J.; Kim, D.; Geva, M.; Rammes, G.; Hayden, M.I. Pridopidine stabilizes mushroom spines in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease by acting on the sigma-1 receptor. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 124, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenkman, M.; Geva, M.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Hayden, M.R.; Lederkremer, G.Z. Pridopidine reduces mutant huntingtin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress by modulation of the Sigma-1 receptor. J. Neurochem. 2021, 158, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Dijak, A.I.; Nassrallah, W.B.; Zhang, L.Y.J.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; Raymond, L.A. Impairment and Restoration of Homeostatic Plasticity in Cultured Cortical Neurons From a Mouse Model of Huntington Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Wu, H.E.; Yasui, Y.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.; Maurice, T.; Cozzolino, M.; Su, T.P. Nucleoporin POM121 signals TFEB-mediated autophagy via activation of SIGMAR1/sigma-1 receptor chaperone by pridopidine. Autophagy 2023, 19, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, S.; Lahaye, R.A.; Vitet, H.; Scaramuzzino, C.; Virlogeux, A.; Capellano, L.; Genoux, A.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Pridopidine rescues BDNF/TrkB trafficking dynamics and synapse homeostasis in a Huntington disease brain-on-a-chip model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 173, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, C.; Ferorelli, S.; Niso, M.; Lovicario, C.; Infantino, V.; Convertini, P.; Perrone, R.; Berardi, F. 2-Aminopyridine derivatives as potential sigma(2) receptor antagonists. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, B.; Bogar, F.; Fulop, L. Protein Folding and Misfolding, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: In Trace of Novel Drug Targets. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2016, 17, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.T.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006, 443, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, C.; Vijayalakshmi, P.; Desai, D.; Manoharan, J. Proteostasis imbalance: Unraveling protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases and emerging therapeutic strategies. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2025, 146, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreser, A.; Vollrath, J.T.; Sechi, A.; Johann, S.; Roos, A.; Yamoah, A.; Katona, I.; Bohlega, S.; Wiemuth, D.; Tian, Y.; et al. The ALS-linked E102Q mutation in Sigma receptor-1 leads to ER stress-mediated defects in protein homeostasis and dysregulation of RNA-binding proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2017, 24, 1655–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollrath, J.T.; Sechi, A.; Dreser, A.; Katona, I.; Wiemuth, D.; Vervoorts, J.; Dohmen, M.; Chandrasekar, A.; Prause, J.; Brauers, E.; et al. Loss of function of the ALS protein SigR1 leads to ER pathology associated with defective autophagy and lipid raft disturbances. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, M.G.; Huesmann, H.; Nagel, H.; Kern, A.; Behl, C. Sigma-1 Receptor Activation Induces Autophagy and Increases Proteostasis Capacity In Vitro and In Vivo. Cells 2019, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gong, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Liu, H.; Li, X. From the regulatory mechanism of TFEB to its therapeutic implications. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristi, A.C.; Rapuri, S.; Coyne, A.N. Nuclear pore complex and nucleocytoplasmic transport disruption in neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 2546–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, A.N.; Rothstein, J.D. Nuclear pore complexes—A doorway to neural injury in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, J.C.; Daigle, J.G.; Arbez, N.; Cunningham, K.C.; Zhang, K.; Ochaba, J.; Geater, C.; Morozko, E.; Stocksdale, J.; Glatzer, J.C.; et al. Mutant Huntingtin Disrupts the Nuclear Pore Complex. Neuron 2017, 94, 93–107.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.J.; La Spada, A.R. TFEB dysregulation as a driver of autophagy dysfunction in neurodegenerative disease: Molecular mechanisms, cellular processes, and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 122, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K.M.; Maulding, K.; Ruan, K.; Senturk, M.; Grima, J.C.; Sung, H.; Zuo, Z.; Song, H.; Gao, J.; Dubey, S.; et al. TFEB/Mitf links impaired nuclear import to autophagolysosomal dysfunction in C9-ALS. Elife 2020, 9, e59419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodicka, P.; Chase, K.; Iuliano, M.; Tousley, A.; Valentine, D.T.; Sapp, E.; Kegel-Gleason, K.B.; Sena-Esteves, M.; Aronin, N.; DiFiglia, M. Autophagy Activation by Transcription Factor EB (TFEB) in Striatum of HDQ175/Q7 Mice. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2016, 5, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunemi, T.; Ashe, T.D.; Morrison, B.E.; Soriano, K.R.; Au, J.; Roque, R.A.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Damian, V.A.; Masliah, E.; La Spada, A.R. PGC-1alpha rescues Huntington’s disease proteotoxicity by preventing oxidative stress and promoting TFEB function. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 142ra97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.T.; Lievens, J.C.; Wang, S.M.; Chuang, J.Y.; Khalil, B.; Wu, H.E.; Chang, W.C.; Maurice, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones rescue nucleocytoplasmic transport deficit seen in cellular and Drosophila ALS/FTD models. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.Y.; Wu, H.E.; Weng, E.F.; Wu, H.C.; Su, T.P.; Wang, S.M. Fluvoxamine Exerts Sigma-1R to Rescue Autophagy via Pom121-Mediated Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of TFEB. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 5282–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, A.N.; Zaepfel, B.L.; Hayes, L.; Fitchman, B.; Salzberg, Y.; Luo, E.C.; Bowen, K.; Trost, H.; Aigner, S.; Rigo, F.; et al. G(4)C(2) Repeat RNA Initiates a POM121-Mediated Reduction in Specific Nucleoporins in C9orf72 ALS/FTD. Neuron 2020, 107, 1124–1140.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baydyuk, M.; Xu, B. BDNF signaling and survival of striatal neurons. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccato, C.; Ciammola, A.; Rigamonti, D.; Leavitt, B.R.; Goffredo, D.; Conti, L.; MacDonald, M.E.; Friedlander, R.M.; Silani, V.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease. Science 2001, 293, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans, A.P.; Horellou, P.; Pradier, L.; Brunet, I.; Colin, P.; Mallet, J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated protection of striatal neurons in an excitotoxic rat model of Huntington’s disease, as demonstrated by adenoviral gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hayden, M.R.; Xu, B. BDNF overexpression in the forebrain rescues Huntington’s disease phenotypes in YAC128 mice. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14708–14718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virlogeux, A.; Moutaux, E.; Christaller, W.; Genoux, A.; Bruyere, J.; Fino, E.; Charlot, B.; Cazorla, M.; Saudou, F. Reconstituting Corticostriatal Network on-a-Chip Reveals the Contribution of the Presynaptic Compartment to Huntington’s Disease. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L.R.; Charrin, B.C.; Borrell-Pages, M.; Dompierre, J.P.; Rangone, H.; Cordelieres, F.P.; De Mey, J.; MacDonald, M.E.; Lessmann, V.; Humbert, S.; et al. Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell 2004, 118, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.D.; Pozzo-Miller, L. The dynamics of excitatory synapse formation on dendritic spines. Cellscience 2009, 5, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.M.; Waxman, S.G. Spinal cord injury, dendritic spine remodeling, and spinal memory mechanisms. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 235, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, C.A.; King, J.F.; Reimer, M.L.; Kauer, S.D.; Waxman, S.G.; Tan, A.M. Dendritic Spines and Pain Memory. Neuroscientist 2024, 30, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ryskamp, D.A.; Liang, X.; Egorova, P.; Zakharova, O.; Hung, G.; Bezprozvanny, I. Enhanced Store-Operated Calcium Entry Leads to Striatal Synaptic Loss in a Huntington’s Disease Mouse Model. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.K.T.; Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S.; Palazzolo, M.J. Exosomes and Homeostatic Synaptic Plasticity Are Linked to Each other and to Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases by Database-Enabled Analyses of Comprehensively Curated Datasets. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.J.; Desai, N.S. Homeostatic Plasticity and STDP: Keeping a Neuron’s Cool in a Fluctuating World. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2010, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Dijak, A.I.; Sepers, M.D.; Raymond, L.A. Alterations in synaptic function and plasticity in Huntington disease. J. Neurochem. 2019, 150, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.; Rymar, V.V.; Sadikot, A.F.; Debonnel, G. Further evidence for an antidepressant potential of the selective sigma1 agonist SA 4503: Electrophysiological, morphological and behavioural studies. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, R.; Debonnel, G. Effects of low and high doses of selective sigma ligands: Further evidence suggesting the existence of different subtypes of sigma receptors. Psychopharmacology 1997, 129, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urani, A.; Romieu, P.; Roman, F.J.; Yamada, K.; Noda, Y.; Kamei, H.; Tran, H.M.; Nagai, T.; Nabeshima, T.; Maurice, T. Enhanced antidepressant efficacy of sigma1 receptor agonists in rats after chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of beta-amyloid-(1-40) protein. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 486, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatematteo, F.S.; Mosier, P.D.; Niso, M.; Brunetti, L.; Berardi, F.; Loiodice, F.; Contino, M.; Delprat, B.; Maurice, T.; Laghezza, A.; et al. Development of novel phenoxyalkylpiperidines as high-affinity Sigma-1 (sigma(1)) receptor ligands with potent anti-amnesic effect. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 228, 114038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mavlyutov, T.; Singh, D.R.; Biener, G.; Yang, J.; Oliver, J.A.; Ruoho, A.; Raicu, V. The sigma-1 receptors are present in monomeric and oligomeric forms in living cells in the presence and absence of ligands. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, U.B.; Ruoho, A.E. Biochemical Pharmacology of the Sigma-1 Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 89, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.P.; Su, T.C.; Nakamura, Y.; Tsai, S.Y. The Sigma-1 Receptor as a Pluripotent Modulator in Living Systems. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) form raft-like microdomains and target lipid droplets on the endoplasmic reticulum: Roles in endoplasmic reticulum lipid compartmentalization and export. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Intracellular dynamics of sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) in NG108-15 cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, N.J.; Colom-Cadena, M.; Riad, A.A.; Xu, J.; Singh, M.; Abate, C.; Cahill, M.A.; Spires-Jones, T.L.; Bowen, W.D.; Mach, R.H.; et al. Proceedings from the Fourth International Symposium on sigma-2 Receptors: Role in Health and Disease. eNeuro 2020, 7, ENEURO.0317-20.2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, A.; Lyu, J.; Braz, J.M.; Tummino, T.A.; Craik, V.; O’Meara, M.J.; Webb, C.M.; Radchenko, D.S.; Moroz, Y.S.; Huang, X.P.; et al. Structures of the sigma(2) receptor enable docking for bioactive ligand discovery. Nature 2021, 600, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Rothfuss, J.; Zhang, J.; Chu, W.; Vangveravong, S.; Tu, Z.; Pan, F.; Chang, K.C.; Hotchkiss, R.; Mach, R.H. Sigma-2 ligands induce tumour cell death by multiple signalling pathways. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakopoulos, G.; Gatos, C.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Christodoulidis, G.; Kagkouras, I.; Trakas, N.; Foroglou, N. Exploring the Role of Sigma Receptors in the Treatment of Cancer: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e70946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.F.; Ma, W.H.; Xie, X.Y.; Huang, Y.S. Sigma-2 Receptor as a Potential Drug Target. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 4172–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, C.; Chu, W.; Pan, F.; Rothfuss, J.M.; Zhang, F.; Tu, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zeng, D.; Vangveravong, S.; et al. Identification of the PGRMC1 protein complex as the putative sigma-2 receptor binding site. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, B.; Sahn, J.J.; Ardestani, P.M.; Evans, A.K.; Scott, L.L.; Chan, J.Z.; Iyer, S.; Crisp, A.; Zuniga, G.; Pierce, J.T.; et al. Small molecule modulator of sigma 2 receptor is neuroprotective and reduces cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesei, A.; Cortesi, M.; Pignatta, S.; Arienti, C.; Dondio, G.M.; Bigogno, C.; Malacrida, A.; Miloso, M.; Meregalli, C.; Chiorazzi, A.; et al. Anti-tumor Efficacy Assessment of the Sigma Receptor Pan Modulator RC-106. A Promising Therapeutic Tool for Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesei, A.; Cortesi, M.; Zamagni, A.; Arienti, C.; Pignatta, S.; Zanoni, M.; Paolillo, M.; Curti, D.; Rui, M.; Rossi, D.; et al. Sigma Receptors as Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress “Gatekeepers” and their Modulators as Emerging New Weapons in the Fight Against Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Hand, R.; Meltzer, M.; Abate, C.; Geva, M.; Hayden, M.R.; Ross, C.A. Sigma-2 receptor antagonism enhances the neuroprotective effects of pridopidine, a Sigma-1 receptor agonist, in Huntington’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 63, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Arbez, N.; Sahn, J.J.; Lu, Y.; Linkens, K.T.; Hodges, T.R.; Tang, A.; Wiseman, R.; Martin, S.F.; Ross, C.A. Neuroprotective Effects of sigma(2)R/TMEM97 Receptor Modulators in the Neuronal Model of Huntington’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limegrover, C.S.; Yurko, R.; Izzo, N.J.; LaBarbera, K.M.; Rehak, C.; Look, G.; Rishton, G.; Safferstein, H.; Catalano, S.M. Sigma-2 receptor antagonists rescue neuronal dysfunction induced by Parkinson’s patient brain-derived alpha-synuclein. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, A.; Zeng, C.; Weng, C.C.; Winters, H.; Xu, K.; Makvandi, M.; Metz, T.; Carlin, S.; Mach, R.H. Sigma-2 Receptor/TMEM97 and PGRMC-1 Increase the Rate of Internalization of LDL by LDL Receptor through the Formation of a Ternary Complex. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizama, B.N.; Keeling, E.; Cho, E.; Malagise, E.M.; Knezovich, N.; Waybright, L.; Watto, E.; Look, G.; Di Caro, V.; Caggiano, A.O.; et al. Sigma-2 receptor modulator CT1812 alters key pathways and rescues retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) functional deficits associated with dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfield, S.R.; Stenn, D.F.; Chen, H.; Kalisch, B.E. A Review of the Clinical Progress of CT1812, a Novel Sigma-2 Receptor Antagonist for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rishton, G.M.; Look, G.C.; Ni, Z.J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, X.; Izzo, N.J.; LaBarbera, K.M.; Limegrover, C.S.; et al. Discovery of Investigational Drug CT1812, an Antagonist of the Sigma-2 Receptor Complex for Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Zaheer, A.B.; Munawwar, A.; Sarfraz, Z.; Sarfraz, A.; Robles-Velasco, K.; Cherrez-Ojeda, I. The Allosteric Antagonist of the Sigma-2 Receptors-Elayta (CT1812) as a Therapeutic Candidate for Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: A Scoping Systematic Review. Life 2022, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Dar, Z.A.; Bajpai, A.; Singh, R.; Bansal, R. Clinical Update on an Anti-Alzheimer Drug Candidate CT1812: A Sigma-2 Receptor Antagonist. Clin. Ther. 2024, 46, e21–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squitieri, F.; Maglione, V.; Di Pardo, A.; Favellato, M.; Frati, L.; Amico, E. Pridopidine, a dopamine stabilizer, improves motor performance and shows neuroprotective effects in Huntington disease R6/2 mouse model. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 2540–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, F.; Ponten, H.; Waters, N.; Waters, S.; Sonesson, C. Synthesis and evaluation of a set of 4-phenylpiperidines and 4-phenylpiperazines as D2 receptor ligands and the discovery of the dopaminergic stabilizer 4-[3-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]-1-propylpiperidine (huntexil, pridopidine, ACR16). J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2510–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesan, S.; Svensson, K.A.; Reckless, G.E.; Nobrega, J.N.; Barlow, K.B.; Johansson, A.M.; Kapur, S. The dopamine stabilizers (S)-(-)-(3-methanesulfonyl-phenyl)-1-propyl-piperidine [(-)-OSU6162] and 4-(3-methanesulfonylphenyl)-1-propyl-piperidine (ACR16) show high in vivo D2 receptor occupancy, antipsychotic-like efficacy, and low potential for motor side effects in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoulson, I.; Fahn, S. Huntington disease: Clinical care and evaluation. Neurology 1979, 29, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, K.; McGarry, A.; McDermott, M.P.; Kayson, E.; Walker, F.; Goldstein, J.; Hyson, C.; Agarwal, P.; Deppen, P.; Fiedorowicz, J.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pridopidine in Huntington’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Yebenes, J.G.; Landwehrmeyer, B.; Squitieri, F.; Reilmann, R.; Rosser, A.; Barker, R.A.; Saft, C.; Magnet, M.K.; Sword, A.; Rembratt, A.; et al. Pridopidine for the treatment of motor function in patients with Huntington’s disease (MermaiHD): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilmann, R.; McGarry, A.; Grachev, I.D.; Savola, J.M.; Borowsky, B.; Eyal, E.; Gross, N.; Langbehn, D.; Schubert, R.; Wickenberg, A.T.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pridopidine in patients with Huntington’s disease (PRIDE-HD): A phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre, dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, A.; Leinonen, M.; Kieburtz, K.; Geva, M.; Olanow, C.W.; Hayden, M. Effects of Pridopidine on Functional Capacity in Early-Stage Participants from the PRIDE-HD Study. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2020, 9, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilmann, R.; Feigin, A.; Rosser, A.E.; Kostyk, S.K.; Saft, C.; Cohen, Y.; Schuring, H.; Hand, R.; Tan, A.M.; Chen, K.; et al. Pridopidine in early-stage manifest Huntington’s disease: A phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3780–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.M.; Geva, M.; Goldberg, Y.P.; Schuring, H.; Sanson, B.J.; Rosser, A.; Raymond, L.; Reilmann, R.; Hayden, M.R.; Anderson, K. Antidopaminergic medications in Huntington’s disease. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2025, 14, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, M.; Goldberg, Y.P.; Schuring, H.; Tan, A.M.; Long, J.D.; Hayden, M.R. Antidopaminergic Medications and Clinical Changes in Measures of Huntington’s Disease: A Causal Analysis. Mov. Disord. 2025, 40, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich-Guilatt, L.; Steiner, L.; Hallak, H.; Pastino, G.; Muglia, P.; Spiegelstein, O. Metoprolol-pridopidine drug-drug interaction and food effect assessments of pridopidine, a new drug for treatment of Huntington’s disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 2214–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellden, A.; Panagiotidis, G.; Johansson, P.; Waters, N.; Waters, S.; Tedroff, J.; Bertilsson, L. The dopaminergic stabilizer pridopidine is to a major extent N-depropylated by CYP2D6 in humans. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilmann, R.; Schubert, R. Motor outcome measures in Huntington disease clinical trials. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 144, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Takahashi, F.; Liu, S.; Tsuda, K.; Palumbo, J. Post-hoc analysis of randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study (MCI186-19) of edaravone (MCI-186) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing, G.; Edaravone, A.L.S.S.G. Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, M.; Shefner, J.; Oskarsson, B.; Lichtenstein, R.G.; Meltzer, M.; Cohen, Y.; Hand, R.; Chen, K.; Leitner, M.; Paganoni, S.; et al. Pridopidine for the Treatment of ALS–Improvements in the Subgroup of Definite, Probable, and Early (<18mo from Onset) Subjects in the Phase 2 Healey ALS Platform Trial (S5.010). Neurology 2025, 104, 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, M.; Goldberg, Y.P.; Leitner, M.L.; Cruz-Herranz, A.; Hand, R.; Chen, K.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Tan, A.M.; Paganoni, S.; Berry, J.; et al. Pridopidine Treatment in ALS: Subgroup Analyses from the HEALEY ALS Platform Trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scleoris Front. Dement. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, B.R.; Thisted, R.A.; Appel, S.H.; Bradley, W.G.; Olney, R.K.; Berg, J.E.; Pope, L.E.; Smith, R.A. for the AVP-923 ALS Study Group. Treatment of pseudobulbar affect in ALS with dextromethorphan/quinidine: A randomized trial. Neurology 2004, 63, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Pioro, E.; Myers, K.; Sirdofsky, M.; Goslin, K.; Meekins, G.; Yu, H.; Wymer, J.; Cudkowicz, M.; Macklin, E.A.; et al. Enhanced Bulbar Function in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: The Nuedexta Treatment Trial. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, A.; Auinger, P.; Kieburtz, K.; Geva, M.; Mehra, M.; Abler, V.; Grachev, I.D.; Gordon, M.F.; Savola, J.M.; Gandhi, S.; et al. Additional Safety and Exploratory Efficacy Data at 48 and 60 Months from Open-HART, an Open-Label Extension Study of Pridopidine in Huntington Disease. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2020, 9, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Writing Committee for the HEALEY ALS Platform Trial; Shefner, J.M.; Oskarsson, B.; Macklin, E.A.; Chibnik, L.B.; Quintana, M.; Saville, B.R.; Detry, M.A.; Vestrucci, M.; Marion, J.; et al. Pridopidine in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: The HEALEY ALS Platform Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darpo, B.; Geva, M.; Ferber, G.; Goldberg, Y.P.; Cruz-Herranz, A.; Mehra, M.; Kovacs, R.; Hayden, M.R. Pridopidine Does Not Significantly Prolong the QTc Interval at the Clinically Relevant Therapeutic Dose. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Y.P.; Navon-Perry, L.; Cruz-Herranz, A.; Chen, K.; Hecker-Barth, G.; Spiegel, K.; Cohen, Y.; Niethammer, M.; Tan, A.M.; Schuring, H.; et al. The Safety Profile of Pridopidine, a Novel Sigma-1 Receptor Agonist for the Treatment of Huntington’s Disease. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. Recent Advances on the Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.H.; Cui, Y.; Huang, S.M.; Zhang, B. The Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling in Central Nervous System Disease Pathogenesis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 924155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanuza, M.A.; Just-Borras, L.; Hurtado, E.; Cilleros-Mane, V.; Tomas, M.; Garcia, N.; Tomas, J. The Impact of Kinases in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at the Neuromuscular Synapse: Insights into BDNF/TrkB and PKC Signaling. Cells 2019, 8, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Dos Santos, A.; Carretero, V.J.; Campano, J.H.; de Pascual, R.; Xu, N.; Lee, S.M.; Wong, C.T.T.; Radis-Baptista, G.; Hernandez-Guijo, J.M. Inhibitory Activity of Calcium and Sodium Ion Channels of Neurotoxic Protoplaythoa variabilis V-Shape Helical Peptide Analogs and Their Neuroprotective Effect In Vitro. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Lei, Y.; Qin, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, P.; Yao, K. Sigma-1 Receptor in Retina: Neuroprotective Effects and Potential Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geva, M.; Gershoni-Emek, N.; Naia, L.; Ly, P.; Mota, S.; Rego, A.C.; Hayden, M.R.; Levin, L.A. Neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells by the sigma-1 receptor agonist pridopidine in models of experimental glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodrea, J.; Tran, M.N.; Besztercei, B.; Medveczki, T.; Szabo, A.J.; Orfi, L.; Kovacs, I.; Fekete, A. Sigma-1 Receptor Agonist Fluvoxamine Ameliorates Fibrotic Response of Trabecular Meshwork Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Haneveld, M.J.; Hieltjes, I.J.; Langendam, M.W.; Cornel, M.C.; Gaasterland, C.M.W.; van Eeghen, A.M. Improving care for rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review and critical appraisal of clinical practice guidelines using AGREE II. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.; Shovlin, S.; Moriarty, M.; Bardoni, B.; Tropea, D. Rett Syndrome and Fragile X Syndrome: Different Etiology With Common Molecular Dysfunctions. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 764761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, S.T.; Deacon, R.M.J.; Guo, S.G.; Altimiras, F.J.; Castillo, J.B.; van der Wildt, B.; Morales, A.P.; Park, J.H.; Klamer, D.; Rosenberg, J.; et al. Effects of the sigma-1 receptor agonist blarcamesine in a murine model of fragile X syndrome: Neurobehavioral phenotypes and receptor occupancy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmon, A.; Herrero, M.; Sharet-Eshed, R.; Gilad, Y.; Senderowitz, H.; Elroy-Stein, O. Drug Screening Identifies Sigma-1-Receptor as a Target for the Therapy of VWM Leukodystrophy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudejans, E.; Witkamp, D.; Hu, A.N.G.V.; Hoogterp, L.; van Rooijen-van Leeuwen, G.; Kruijff, I.; Schonewille, P.; El Mouttalibi, Z.L.; Bartelink, I.; van der Knaap, M.S.; et al. Pridopidine subtly ameliorates motor skills in a mouse model for vanishing white matter. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202302199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzier, L.; Danese, A.; Yasui, Y.; Richard, E.M.; Lievens, J.C.; Patergnani, S.; Couly, S.; Diez, C.; Denus, M.; Cubedo, N.; et al. Activation of the sigma-1 receptor chaperone alleviates symptoms of Wolfram syndrome in preclinical models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabh3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Family | Compound | Ki for S1R | S1R Activity | Ki for Other Target | Fold Selectivity for S1R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1R agonist in development | Pridopidine | 57 nM | agonist | ADRα2; 1600 nM | 28 |

| Blarcamesine | 3700 nM | agonist | M1; 500 nM | 0.14 | |

| S1R agonist/ NMDAR antagonist | Dextromethorphan | ~100 nM | agonist | NMDAR; 500 nM | 5 |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | Donepezil | 14.6 nM | agonist | AChEi; 5.7 nM | 0.4 |

| Antipsychotic | Chlorpromazine | 180 nM | antagonist | D1R, 56 nM | 0.3 |

| Haloperidol | 3.7 nM | antagonist | D2R; 0.89 nM | 0.24 | |

| Antidepressants | Imipramine | ~500 nM | agonist | SERT, 1–3 nM | <0.05 |

| Fluoxetine | 240 nM | agonist | |||

| Citalopram | 292 nM | agonist | |||

| Fluvoxamine | 36 nM | agonist | |||

| Sertraline | 57 nM | antagonist |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gershoni Emek, N.; Tan, A.M.; Geva, M.; Fekete, A.; Abate, C.; Hayden, M.R. Pridopidine, a Potent and Selective Therapeutic Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Agonist for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121900

Gershoni Emek N, Tan AM, Geva M, Fekete A, Abate C, Hayden MR. Pridopidine, a Potent and Selective Therapeutic Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Agonist for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121900

Chicago/Turabian StyleGershoni Emek, Noga, Andrew M. Tan, Michal Geva, Andrea Fekete, Carmen Abate, and Michael R. Hayden. 2025. "Pridopidine, a Potent and Selective Therapeutic Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Agonist for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121900

APA StyleGershoni Emek, N., Tan, A. M., Geva, M., Fekete, A., Abate, C., & Hayden, M. R. (2025). Pridopidine, a Potent and Selective Therapeutic Sigma-1 Receptor (S1R) Agonist for Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121900