In Silico Identification of Molecular Interactions of the Emerging Contaminant Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) on HPT Axis: Implications for Humans and Zebrafish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Docking

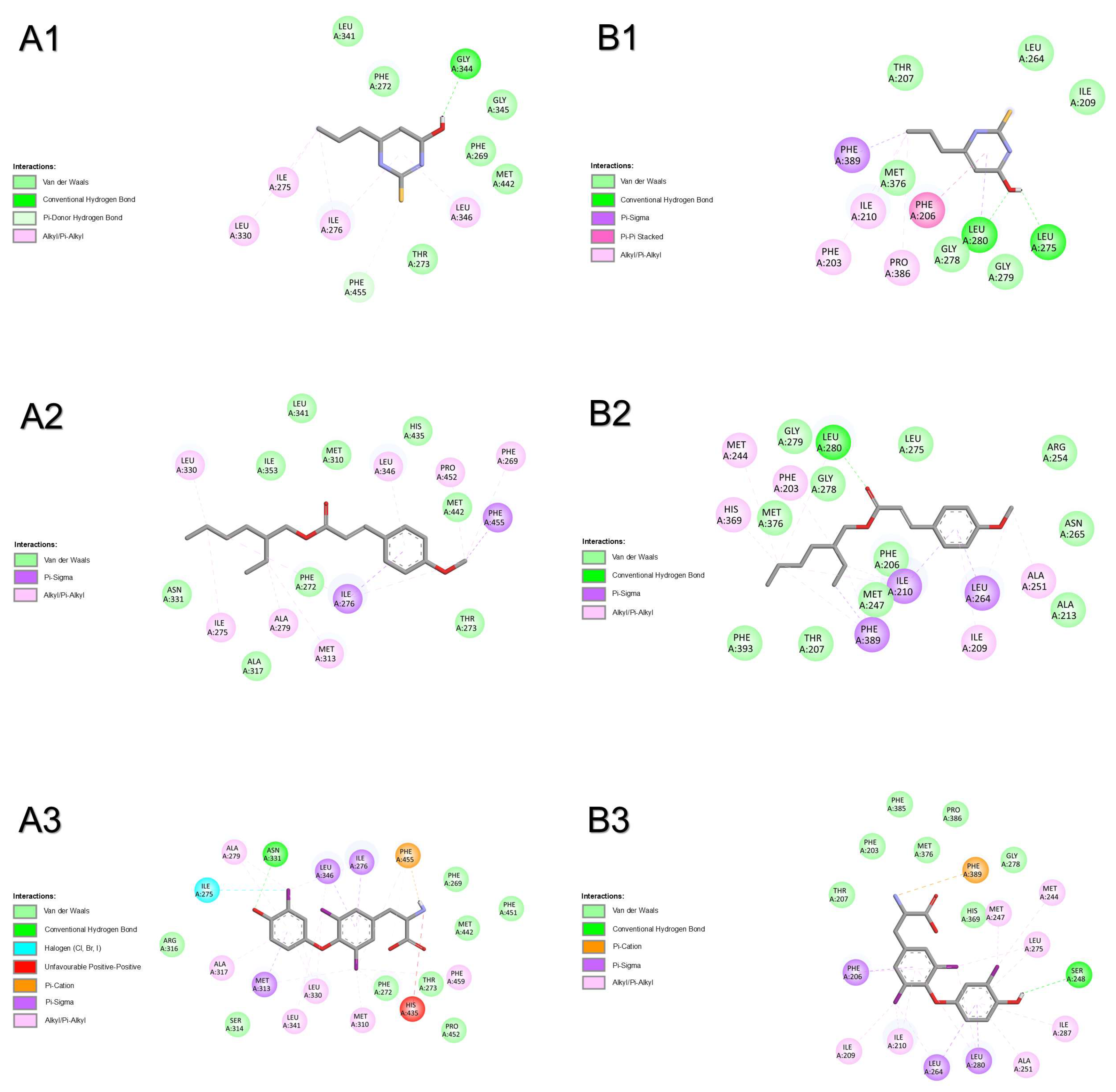

2.1.1. Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor

2.1.2. Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor 2

2.1.3. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor

2.1.4. Transthyretin

2.1.5. Thyroid Hormone Receptor Alpha

2.1.6. Thyroid Hormone Receptor Beta

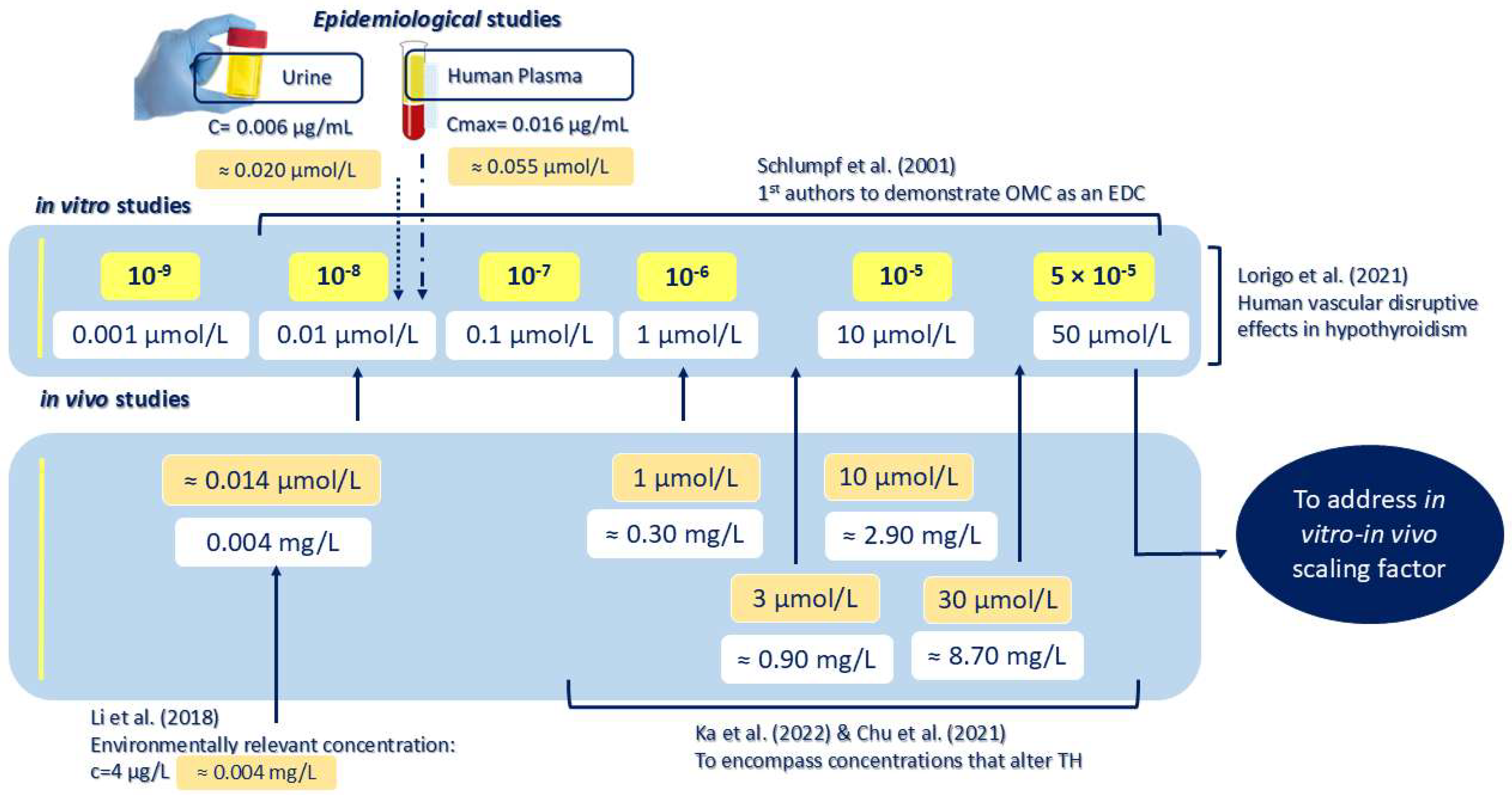

3. Discussion

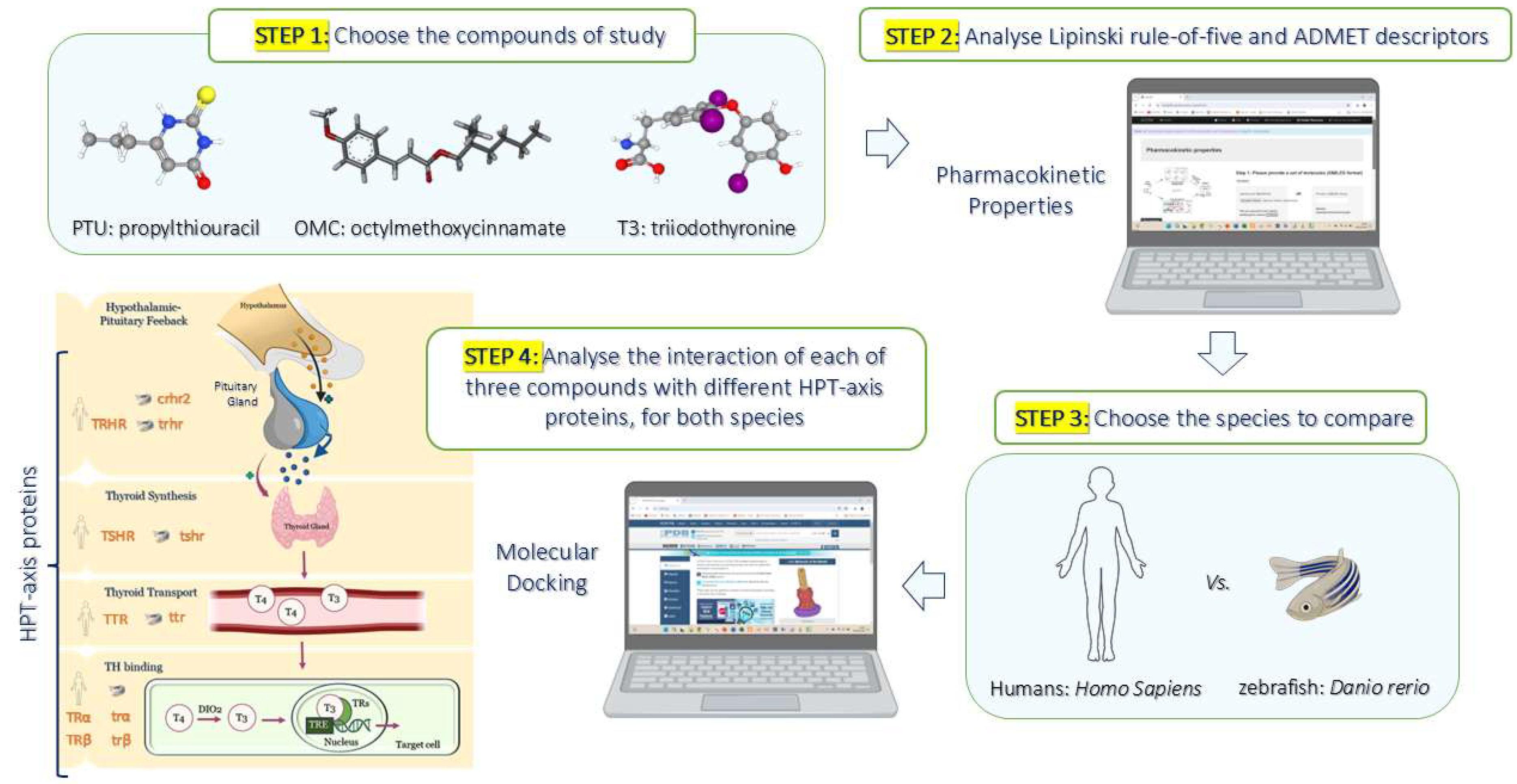

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Prediction of Pharmacokinetic Properties by Computational Analysis

4.2. In Silico Simulations by Molecular Docking

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yen, P.M. Physiological and molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 1097–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. New Scoping Document on In Vitro and Ex Vivo Assays for the Identification of Modulators of Thyroid Hormone Signalling; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noyes, P.D.; Friedman, K.P.; Browne, P.; Haselman, J.T.; Gilbert, M.E.; Hornung, M.W.; Barone, S., Jr.; Crofton, K.M.; Laws, S.C.; Stoker, T.E.; et al. Evaluating chemicals for thyroid disruption: Opportunities and challenges with in vitro testing and adverse outcome pathway approaches. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 95001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramhoj, L.; Axelstad, M.; Baert, Y.; Canas-Portilla, A.I.; Chalmel, F.; Dahmen, L.; De La Vieja, A.; Evrard, B.; Haigis, A.C.; Hamers, T.; et al. New approach methods to improve human health risk assessment of thyroid hormone system disruption-a parc project. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1189303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sharif, M.; Tsakovska, I.; Pajeva, I.; Alov, P.; Fioravanzo, E.; Bassan, A.; Kovarich, S.; Yang, C.; Mostrag-Szlichtyng, A.; Vitcheva, V.; et al. The application of molecular modelling in the safety assessment of chemicals: A case study on ligand-dependent ppargamma dysregulation. Toxicology 2017, 392, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, J. Identification of molecular initiating events (mie) using chemical database analysis and nuclear receptor activity assays for screening potential inhalation toxicants. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. RTP 2023, 141, 105391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Burden, N.; Bonnell, M.; Hecker, M.; Hutchinson, T.H.; Jagla, M.; LaLone, C.A.; Lagadic, L.; Lynn, S.G.; Shore, B.; et al. New approach methodologies for the endocrine activity toolbox: Environmental assessment for fish and amphibians. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golz, L.; Blanc-Legendre, M.; Rinderknecht, M.; Behnstedt, L.; Coordes, S.; Reger, L.; Sire, S.; Cousin, X.; Braunbeck, T.; Baumann, L. Development of a zebrafish embryo-based test system for thyroid hormone system disruption: 3rs in ecotoxicological research. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 44, 2485–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Anselmo, C.; Sardela, V.F.; de Sousa, V.P.; Pereira, H.M.G. Zebrafish (Danio rerio): A valuable tool for predicting the metabolism of xenobiotics in humans? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 212, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducharme, N.A.; Reif, D.M.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Bondesson, M. Comparison of toxicity values across zebrafish early life stages and mammalian studies: Implications for chemical testing. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 55, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kari, G.; Rodeck, U.; Dicker, A.P. Zebrafish: An emerging model system for human disease and drug discovery. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 82, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotrina, E.Y.; Oliveira, A.; Llop, J.; Quintana, J.; Biarnes, X.; Cardoso, I.; Diaz-Cruz, M.S.; Arsequell, G. Binding of common organic uv-filters to the thyroid hormone transport protein transthyretin using in vitro and in silico studies: Potential implications in health. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siller, A.; Blaszak, S.C.; Lazar, M.; Olasz Harken, E. Update about the effects of the sunscreen ingredients oxybenzone and octinoxate on humans and the environment. Plast. Surg. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Soc. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Nurses 2019, 39, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.C.P.; Santos, B.; Castro, H.C.; Rodrigues, C.R. Ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate and butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane: Toxicological effects on marine biota and human concerns. J. Appl. Toxicol. JAT 2022, 42, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fivenson, D.; Sabzevari, N.; Qiblawi, S.; Blitz, J.; Norton, B.B.; Norton, S.A. Sunscreens: Uv filters to protect us: Part 2-increasing awareness of uv filters and their potential toxicities to us and our environment. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2021, 7, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Exposure to uv-b filter octylmethoxycinnamate and human health effects: Focus on endocrine disruptor actions. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Effects associated with exposure to the emerging contaminant octyl-methoxycinnamate (a uv-b filter) in the aquatic environment: A review. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2024, 27, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmutzler, C.; Gotthardt, I.; Hofmann, P.J.; Radovic, B.; Kovacs, G.; Stemmler, L.; Nobis, I.; Bacinski, A.; Mentrup, B.; Ambrugger, P.; et al. Endocrine disruptors and the thyroid gland—A combined in vitro and in vivo analysis of potential new biomarkers. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Song, M.K.; Choi, H.S.; Ryu, J.C. Monitoring of deiodinase deficiency based on transcriptomic responses in sh-sy5y cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Uv-b filter octylmethoxycinnamate alters the vascular contractility patterns in pregnant women with hypothyroidism. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Kwon, B.R.; Lee, Y.M.; Zoh, K.D.; Choi, K. Effects of 2-ethylhexyl-4-methoxycinnamate (ehmc) on thyroid hormones and genes associated with thyroid, neurotoxic, and nephrotoxic responses in adult and larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka, Y.; Ji, K. Waterborne exposure to avobenzone and octinoxate induces thyroid endocrine disruption in wild-type and thralphaa(-/-) zebrafish larvae. Ecotoxicology 2022, 31, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reum Kwon, B.; Jo, A.R.; Lee, I.; Lee, G.; Joo Park, Y.; Pyo Lee, J.; Park, N.Y.; Kho, Y.; Kim, S.; Ji, K.; et al. Thyroid, neurodevelopmental, and kidney toxicities of common organic uv filters in embryo-larval zebrafish (Danio rerio), and their potential links. Environ. Int. 2024, 192, 109030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.T.; Scapolla, C.; Di Carro, M.; Magi, E. Rapid and selective determination of uv filters in seawater by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry combined with stir bar sorptive extraction. Talanta 2011, 85, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, M.E.; Buser, H.R.; Muller, M.D.; Poiger, T. Occurrence of some organic uv filters in wastewater, in surface waters, and in fish from swiss lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fent, K.; Zenker, A.; Rapp, M. Widespread occurrence of estrogenic uv-filters in aquatic ecosystems in Switzerland. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Cruz, M.S.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Llorca, M.; Barcelo, D. Analysis of uv filters in tap water and other clean waters in Spain. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 2325–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Law, J.C.; Lam, T.K.; Leung, K.S. Risks of organic uv filters: A review of environmental and human health concern studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjua, N.R.; Kongshoj, B.; Andersson, A.M.; Wulf, H.C. Sunscreens in human plasma and urine after repeated whole-body topical application. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2008, 22, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlumpf, M.; Kypke, K.; Wittassek, M.; Angerer, J.; Mascher, H.; Mascher, D.; Vokt, C.; Birchler, M.; Lichtensteiger, W. Exposure patterns of uv filters, fragrances, parabens, phthalates, organochlor pesticides, pbdes, and pcbs in human milk: Correlation of uv filters with use of cosmetics. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, L.; Alamer, M.; Darbre, P.D. Measurement of concentrations of four chemical ultraviolet filters in human breast tissue at serial locations across the breast. J. Appl. Toxicol. JAT 2018, 38, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, F.; Lu, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, S.; Shen, Z.; Yu, X.; Yuan, T. Exploring environmental obesogenous effects of organic ultraviolet filters on children from a case-control study. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 139883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, K.H.; Reid, M.J.; Fjeld, E.; Oxnevad, S.; Thomas, K.V. Environmental occurrence and risk of organic uv filters and stabilizers in multiple matrices in Norway. Environ. Int. 2015, 80, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, M.B.; Feo, M.L.; Corcellas, C.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Bertozzi, C.P.; Marigo, J.; Flach, L.; Meirelles, A.C.; Carvalho, V.L.; Azevedo, A.F.; et al. Toxic heritage: Maternal transfer of pyrethroid insecticides and sunscreen agents in dolphins from Brazil. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinwald, H.; Konig, A.; Ayobahan, S.U.; Alvincz, J.; Sipos, L.; Gockener, B.; Bohle, G.; Shomroni, O.; Hollert, H.; Salinas, G.; et al. Toxicogenomic fin(ger)prints for thyroid disruption aop refinement and biomarker identification in zebrafish embryos. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Revised Guidance Document 150 on Standardised Test Guidelines for Evaluating Chemicals for Endocrine Disruption; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Tg 248: Xenopus Eleutheroembryonic Thyroid Assay (XETA); OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa, B.; Hermsen, S.A.; Kessels, M.Y.; van den Berg, J.H.; Peijnenburg, A.A.; Aarts, J.M.; Piersma, A.H.; Rietjens, I.M. Developmental toxicity of thyroid-active compounds in a zebrafish embryotoxicity test. Altex 2014, 31, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, K.M.; Miller, G.W.; Chen, X.; Harvey, D.J.; Puschner, B.; Lein, P.J. Changes in thyroid hormone activity disrupt photomotor behavior of larval zebrafish. Neurotoxicology 2019, 74, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Jing, P.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, H. Thyroid hormone in the pathogenesis of congenital intestinal dysganglionosis. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2020, 23, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonyushkina, K.N.; Krug, S.; Ortiz-Toro, T.; Mascari, T.; Karlstrom, R.O. Low thyroid hormone levels disrupt thyrotrope development. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 2774–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groef, B.; Van der Geyten, S.; Darras, V.M.; Kuhn, E.R. Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone as a thyrotropin-releasing factor in non-mammalian vertebrates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 146, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Silva, A.P.; Andrade, M.N.; Pereira-Rodrigues, P.; Paiva-Melo, F.D.; Soares, P.; Graceli, J.B.; Dias, G.R.M.; Ferreira, A.C.F.; de Carvalho, D.P.; Miranda-Alves, L. Frontiers in endocrine disruption: Impacts of organotin on the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 460, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takefuji, M.; Murohara, T. Corticotropin-releasing hormone family and their receptors in the cardiovascular system. Circ. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circ. Soc. 2019, 83, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Khan, K.; Khan, S.W.; Ur Rashid, H.; Irum; Zahoor, M.; Umar, M.N.; Ullah, R.; Ali, E.A. Homology modeling and molecular docking study of corticotrophin-releasing hormone: An approach to treat stress-related diseases. Open Chem. 2024, 22, 20240069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerson, T.P.; Kauer, J.; Wolfe, H.C.; Mobtaker, H.; Wu, P.; Jackson, I.M.; Lechan, R.M. Thyroid hormone regulates trh biosynthesis in the paraventricular nucleus of the rat hypothalamus. Science 1987, 238, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, D.S.; Jones, R.A.; Miller, T.C. Thyrotropin in teleost fish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2009, 161, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shupnik, M.A.; Chin, W.W.; Habener, J.F.; Ridgway, E.C. Transcriptional regulation of the thyrotropin subunit genes by thyroid hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 2900–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.Y.; Dong, Y.J.; Chen, L.N.; Zang, S.K.; Wang, J.; Shen, D.D.; Guo, J.; Qin, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.W.; et al. Molecular basis for the activation of thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Ma, Z.; Feng, X.; Huang, R.; An, Q.; Pan, Y.; Chang, J.; Wan, B.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Comparative assessment of thyroid disrupting effects of ethiprole and its metabolites: In silico, in vitro, and in vivo study. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 155, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Gui, B.; Yuan, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Su, L. Application of machine learning to predict the inhibitory activity of organic chemicals on thyroid stimulating hormone receptor. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Begum, A.; Brannstrom, K.; Grundstrom, C.; Iakovleva, I.; Olofsson, A.; Sauer-Eriksson, A.E.; Andersson, P.L. Structure-based virtual screening protocol for in silico identification of potential thyroid disrupting chemicals targeting transthyretin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11984–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, S.J. Cell and molecular biology of transthyretin and thyroid hormones. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2007, 258, 137–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, H.; Kwon, B.R.; Lee, S.; Moon, H.B.; Choi, K. Adverse thyroid hormone and behavioral alterations induced by three frequently used synthetic musk compounds in embryo-larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahova, J.; Blahova, J.; Mares, J.; Hodkovicova, N.; Sauer, P.; Kroupova, H.K.; Svobodova, Z. Octinoxate as a potential thyroid hormone disruptor—A combination of in vivo and in vitro data. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, N.; Ahmadi, F.; Sadiqi, M.; Ziemnicka, K.; Minczykowski, A. Thyroid gland dysfunction and its effect on the cardiovascular system: A comprehensive review of the literature. Endokrynol. Pol. 2020, 71, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaker, L.; Razvi, S.; Bensenor, I.M.; Azizi, F.; Pearce, E.N.; Peeters, R.P. Hypothyroidism. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, I.A.; Beg, M.A.; Hamoda, T.A.A.; Mandourah, H.M.S.; Memili, E. An analysis of the structural relationship between thyroid hormone-signaling disruption and polybrominated diphenyl ethers: Potential implications for male infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zughaibi, T.A.; Sheikh, I.A.; Beg, M.A. Insights into the endocrine disrupting activity of emerging non-phthalate alternate plasticizers against thyroid hormone receptor: A structural perspective. Toxics 2022, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, M.A.; Sheikh, I.A. Endocrine disruption: Molecular interactions of environmental bisphenol contaminants with thyroid hormone receptor and thyroxine-binding globulin. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2020, 36, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.F.; Lin, Z.C.; Lu, S.Q.; Chen, X.F.; Liao, X.L.; Qi, Z.; Cai, Z. Azole-induced color vision deficiency associated with thyroid hormone signaling: An integrated in vivo, in vitro, and in silico study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13264–13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, Q.S.; Sun, Z.; Ren, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Assessment of thyroid endocrine disruption effects of parabens using in vivo, in vitro, and in silico approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ning, X.; Li, G.; Sang, N. Exposure to oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and endocrine dysfunction: Multi-level study based on hormone receptor responses. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.; Kar, A.; Singh, M.; Singh, R.K.; Ganeshpurkar, A. Syringic acid, a novel thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonist, ameliorates propylthiouracil-induced thyroid toxicity in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2021, 35, e22814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, F.; Rong, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, P.; Long, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, T.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Yang, H. Insights into spirotetramat-induced thyroid disruption during zebrafish (Danio rerio) larval development: An integrated approach with in vivo, in vitro, and in silico analyses. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul-Friedman, K.; Martin, M.; Crofton, K.M.; Hsu, C.W.; Sakamuru, S.; Zhao, J.; Xia, M.; Huang, R.; Stavreva, D.A.; Soni, V.; et al. Limited chemical structural diversity found to modulate thyroid hormone receptor in the tox21 chemical library. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 97009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Chen, Q.; Hong, H.; Benfenati, E.; Gini, G.C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Shi, W. Structures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals correlate with the activation of 12 classic nuclear receptors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16552–16562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; Zhu, Y. A new perspective on thyroid hormones: Crosstalk with reproductive hormones in females. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paisdzior, S.; Schuelke, M.; Krude, H. What is the role of thyroid hormone receptor alpha 2 (tralpha2) in human physiology? Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2022, 130, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.J.; Law, J.C.; Chow, C.H.; Huang, Y.; Li, K.; Leung, K.S. Joint effects of multiple uv filters on zebrafish embryo development. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9460–9467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, L.; Ros, A.; Rehberger, K.; Neuhauss, S.C.; Segner, H. Thyroid disruption in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae: Different molecular response patterns lead to impaired eye development and visual functions. Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 172, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, L.; Segner, H.; Ros, A.; Knapen, D.; Vergauwen, L. Thyroid hormone disruptors interfere with molecular pathways of eye development and function in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, K.M.; Miller, G.W.; Chen, X.; Yaghoobi, B.; Puschner, B.; Lein, P.J. Effects of thyroid hormone disruption on the ontogenetic expression of thyroid hormone signaling genes in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 272, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannetier, P.; Poulsen, R.; Golz, L.; Coordes, S.; Stegeman, H.; Koegst, J.; Reger, L.; Braunbeck, T.; Hansen, M.; Baumann, L. Reversibility of thyroid hormone system-disrupting effects on eye and thyroid follicle development in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2023, 42, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, M.; Golz, L.; Rinderknecht, M.; Koegst, J.; Braunbeck, T.; Baumann, L. Developmental exposure to triclosan and benzophenone-2 causes morphological alterations in zebrafish (Danio rerio) thyroid follicles and eyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 33711–33724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinckens, E.; Vergauwen, L.; Ankley, G.T.; Blust, R.; Darras, V.M.; Villeneuve, D.L.; Witters, H.; Volz, D.C.; Knapen, D. An aop-based alternative testing strategy to predict the impact of thyroid hormone disruption on swim bladder inflation in zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 200, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Z.; Arena, M.; Kienzler, A. Fish toxicity testing for identification of thyroid disrupting chemicals. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaan, K.; Haigis, A.C.; Weiss, J.; Legradi, J. Effects of 25 thyroid hormone disruptors on zebrafish embryos: A literature review of potential biomarkers. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbar, A.; Pingitore, A.; Pearce, S.H.; Zaman, A.; Iervasi, G.; Razvi, S. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat. reviews. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichiki, T. Thyroid hormone and vascular remodeling. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016, 23, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariana, M.; Soares, A.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Cairrao, E. Exposure to dep modifies the human umbilical artery vascular resistance contributing to hypertension in pregnancy. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, M.I.; Lorigo, M.; Cairrao, E. Evaluation of the bisphenol a-induced vascular toxicity on human umbilical artery. Environ. Res. 2023, 226, 115628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiteiro, J.; Rocha, S.M.; Mariana, M.; Maia, C.J.; Cairrao, E. Pathways involved in the human vascular tetrabromobisphenol a response: Calcium and potassium channels and nitric oxide donors. Toxicology 2022, 470, 153158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlumpf, M.; Cotton, B.; Conscience, M.; Haller, V.; Steinmann, B.; Lichtensteiger, W. In vitro and in vivo estrogenicity of uv screens. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ptak, D.; Zhang, L.; Walls, E.K.; Zhong, W.; Leung, Y.F. Phenylthiourea specifically reduces zebrafish eye size. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmi, P.; Giri, V.; Zickgraf, F.M.; Haake, V.; Henkes, S.; Driemert, P.; Michaelis, P.; Busch, W.; Scholz, S.; Flick, B.; et al. A metabolomics approach to reveal the mechanism of developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos exposed to 6-propyl-2-thiouracil. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 382, 110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Yuan, M.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X. Evaluation of structurally different brominated flame retardants interacting with the transthyretin and their toxicity on hepg2 cells. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Hogstrand, C.; Xue, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Li, D.; Yu, L. Bioaccumulation and thyroid endcrione disruption of 2-ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate at environmental concentration in zebrafish larvae. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 267, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte-Guterman, P.; Navarro-Martin, L.; Trudeau, V.L. Mechanisms of crosstalk between endocrine systems: Regulation of sex steroid hormone synthesis and action by thyroid hormones. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2014, 203, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergauwen, L.; Bajard, L.; Tait, S.; Langezaal, I.; Sosnowska, A.; Roncaglioni, A.; Hessel, E.; van den Brand, A.D.; Haigis, A.C.; Novak, J.; et al. A 2024 inventory of test methods relevant to thyroid hormone system disruption for human health and environmental regulatory hazard assessment. Open Res. Eur. 2024, 4, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinken, M.; Knapen, D.; Vergauwen, L.; Hengstler, J.G.; Angrish, M.; Whelan, M. Adverse outcome pathways: A concise introduction for toxicologists. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 3697–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhne, R.; Hilscherova, K.; Smutna, M.; Lessmollmann, F.; Schuurmann, G. In silico bioavailability triggers applied to direct and indirect thyroid hormone disruptors. Chemosphere 2024, 348, 140611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.H.; Hong, C.C. Zebrafish small molecule screens: Taking the phenotypic plunge. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Mangana, C.; Cairrao, E. Disrupting effects of the emerging contaminant octylmethoxycinnamate (OMC) on human umbilical artery relaxation. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Uv-b filter octylmethoxycinnamate is a modulator of the serotonin and histamine receptors in human umbilical arteries. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Maia, C.J.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Uv-b filter octylmethoxycinnamate impaired the main vasorelaxant mechanism of human umbilical artery. Chemosphere 2021, 277, 130302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Lemos, M.C.; Martinez-de-Oliveira, J.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Uv-b Filter octylmethoxycinnamate induces vasorelaxation by Ca(2+) channel inhibition and guanylyl cyclase activation in human umbilical arteries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiani, E.; Sella, F.; Astolfi, P.; Galeazzi, R.; Carnevali, O.; Maradonna, F. First in vivo insights on the effects of tempol-methoxycinnamate, a new uv filter, as alternative to octyl methoxycinnamate, on zebrafish early development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nataraj, B.; Maharajan, K.; Hemalatha, D.; Rangasamy, B.; Arul, N.; Ramesh, M. Comparative toxicity of uv-filter octyl methoxycinnamate and its photoproducts on zebrafish development. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 134546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Lu, G.; Yan, Z.; Jiang, R.; Shen, J.; Bao, X. Parental transfer of ethylhexyl methoxy cinnamate and induced biochemical responses in zebra fish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 206, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshavsky, J.; Smith, A.; Wang, A.; Hom, E.; Izano, M.; Huang, H.; Padula, A.; Woodruff, T.J. Heightened susceptibility: A review of how pregnancy and chemical exposures influence maternal health. Reprod. Toxicol. 2020, 92, 14–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maipas, S.; Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P. Sun lotion chemicals as endocrine disruptors. Hormones (Athens) 2015, 14, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, M.; Klit, A.; Jensen, M.B.; Soeborg, T.; Frederiksen, H.; Schlumpf, M.; Lichtensteiger, W.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Drzewiecki, K.T. Sunscreens: Are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of uv-filters. Int. J. Androl. 2012, 35, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, M.K.; Florian, J.; Zusterzeel, R.; Pilli, N.R.; Patel, V.; Volpe, D.A.; Yang, Y.; Oh, L.; Bashaw, E.; Zineh, I.; et al. Effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration of sunscreen active ingredients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelstad, M.; Boberg, J.; Hougaard, K.S.; Christiansen, S.; Jacobsen, P.R.; Mandrup, K.R.; Nellemann, C.; Lund, S.P.; Hass, U. Effects of pre- and postnatal exposure to the uv-filter octyl methoxycinnamate (omc) on the reproductive, auditory and neurological development of rat offspring. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 250, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwarcfarb, B.; Carbone, S.; Reynoso, R.; Bollero, G.; Ponzo, O.; Moguilevsky, J.; Scacchi, P. Octyl-methoxycinnamate (omc), an ultraviolet (uv) filter, alters lhrh and amino acid neurotransmitters release from hypothalamus of immature rats. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2008, 116, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Szwarcfarb, B.; Reynoso, R.; Ponzo, O.J.; Cardoso, N.; Ale, E.; Moguilevsky, J.A.; Scacchi, P. In vitro effect of octyl—Methoxycinnamate (omc) on the release of gn-rh and amino acid neurotransmitters by hypothalamus of adult rats. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2010, 118, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtensteiger, W.; Bassetti-Gaille, C.; Faass, O.; Axelstad, M.; Boberg, J.; Christiansen, S.; Rehrauer, H.; Georgijevic, J.K.; Hass, U.; Kortenkamp, A.; et al. Differential gene expression patterns in developing sexually dimorphic rat brain regions exposed to antiandrogenic, estrogenic, or complex endocrine disruptor mixtures: Glutamatergic synapses as target. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 1477–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela-Soria, F.; Gallardo-Torres, M.E.; Ballesteros, O.; Diaz, C.; Perez, J.; Navalon, A.; Fernandez, M.F.; Olea, N. Assessment of parabens and ultraviolet filters in human placenta tissue by ultrasound-assisted extraction and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1487, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlumpf, M.; Kypke, K.; Vöt, C.C.; Birchler, M.; Durrer, S.; Faass, O.; Ehnes, C.; Fuetsch, M.; Gaille, C.; Henseler, M.; et al. Endocrine active uv filters:: Developmental toxicity and exposure through breast milk. Chimia 2008, 62, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintaneiro, C.; Teixeira, B.; Benede, J.L.; Chisvert, A.; Soares, A.; Monteiro, M.S. Toxicity effects of the organic uv-filter 4-methylbenzylidene camphor in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Lee, B.H.; Song, S.H.; Kim, M.K. Revisiting the ramachandran plot based on statistical analysis of static and dynamic characteristics of protein structures. J. Struct. Biol. 2023, 215, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubec, D.; Skoda, P.; Krivak, R.; Novotny, M.; Hoksza, D. Prankweb 3: Accelerated ligand-binding site predictions for experimental and modelled protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W593–W597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivak, R.; Hoksza, D. P2rank: Machine learning based tool for rapid and accurate prediction of ligand binding sites from protein structure. J. Cheminform. 2018, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, K.A.; Altman, R.B. Databases of ligand-binding pockets and protein-ligand interactions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 1320–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. Autodock vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. Autodock vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulifa, D.L.; Amirah, S.R.; Rahayu, D.; Megantara, S.; Muchtaridi, M. Pharmacophore modeling and binding affinity of secondary metabolites from angelica keiskei to hmg co-a reductase. Molecules 2024, 29, 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmic, P. A steady state mathematical model for stepwise “slow-binding” reversible enzyme inhibition. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 380, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, A.; El Harrad, L.; Arduini, F.; Moscone, D.; Palleschi, G. Analytical aspects of enzyme reversible inhibition. Talanta 2014, 118, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaru, R.; Orchard, S.; UniProt, C. Uniprot tools: Blast, align, peptide search, and id mapping. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, E697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Compound | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ki (µmol/L) | H-Bridges | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRHR | T3 | −8.01 | 1.34 | ALA78 (2.454 Å) | H. sapiens (Humans) |

| PTU | −4.06 | 1060.00 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −5.21 | 150.97 | N/A | ||

| trhr | T3 | −6.86 | 9.33 | N/A | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| PTU | −4.53 | 477.19 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −5.77 | 59.27 | N/A | ||

| crhr2 | T3 | −0.13 | 809,260.00 | N/A | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| PTU | −5.50 | 92.27 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −6.45 | 18.6 | N/A | ||

| TSHR | T3 | −4.50 | 504.63 | GLN489 (2.631 Å) | H. sapiens (Humans) |

| PTU | −4.66 | 385.30 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −5.68 | 68.23 | N/A | ||

| tshr | T3 | −5.60 | 78.04 | N/A | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| PTU | −4.41 | 585.23 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −5.86 | 50.89 | N/A | ||

| TTR | T3 | −5.75 | 60.88 | N/A | H. sapiens (Humans) |

| T4 | −5.06 | 196.03 | N/A | ||

| PTU | −3.44 | 3010.00 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −3.66 | 2090.00 | N/A | ||

| ttr | T3 | −5.88 | 49.31 | (LEU132, 2.426 Å and SER137, 2.076 Å) | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| T4 | −5.11 | 179.92 | N/A | ||

| PTU | −3.60 | 2300.00 | (ALA130, 2.270 Å) | ||

| OMC | −3.53 | 2600.00 | N/A | ||

| TRα | T3 | −4.54 | 468.17 | ILE378 (2.203 Å) | H. sapiens (Humans) |

| PTU | −4.63 | 407.09 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −6.92 | 8.49 | N/A | ||

| trα | T3 | −6.42 | 19.81 | N/A | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| PTU | −5.23 | 146.05 | N/A | ||

| OMC | −7.83 | 1.83 | N/A | ||

| TRβ | T3 | −6.48 | 17.77 | N/A | H. sapiens (Humans) |

| PTU | −5.39 | 112.22 | (THR329, 2.323 Å) | ||

| OMC | −7.88 | 1.68 | N/A | ||

| trβ | T3 | −5.95 | 43.82 | (MET247, 1.872 Å) | D. rerio (Zebrafish) |

| PTU | −5.50 | 92.64 | (ASN265, 2.027 Å) | ||

| OMC | −8.13 | 1.09 | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorigo, M.; Breitenfeld, L.; Monteiro, M.S.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Cairrao, E. In Silico Identification of Molecular Interactions of the Emerging Contaminant Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) on HPT Axis: Implications for Humans and Zebrafish. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121897

Lorigo M, Breitenfeld L, Monteiro MS, Soares AMVM, Quintaneiro C, Cairrao E. In Silico Identification of Molecular Interactions of the Emerging Contaminant Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) on HPT Axis: Implications for Humans and Zebrafish. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121897

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorigo, Margarida, Luiza Breitenfeld, Marta S. Monteiro, Amadeu M. V. M. Soares, Carla Quintaneiro, and Elisa Cairrao. 2025. "In Silico Identification of Molecular Interactions of the Emerging Contaminant Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) on HPT Axis: Implications for Humans and Zebrafish" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121897

APA StyleLorigo, M., Breitenfeld, L., Monteiro, M. S., Soares, A. M. V. M., Quintaneiro, C., & Cairrao, E. (2025). In Silico Identification of Molecular Interactions of the Emerging Contaminant Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) on HPT Axis: Implications for Humans and Zebrafish. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121897