Production of a Dulaglutide Analogue by Apoptosis-Resistant Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in a 3-Week Fed-Batch Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Design of Expression Constructs

2.2. Generation and Amplification of a DHFR-Selectable Pool

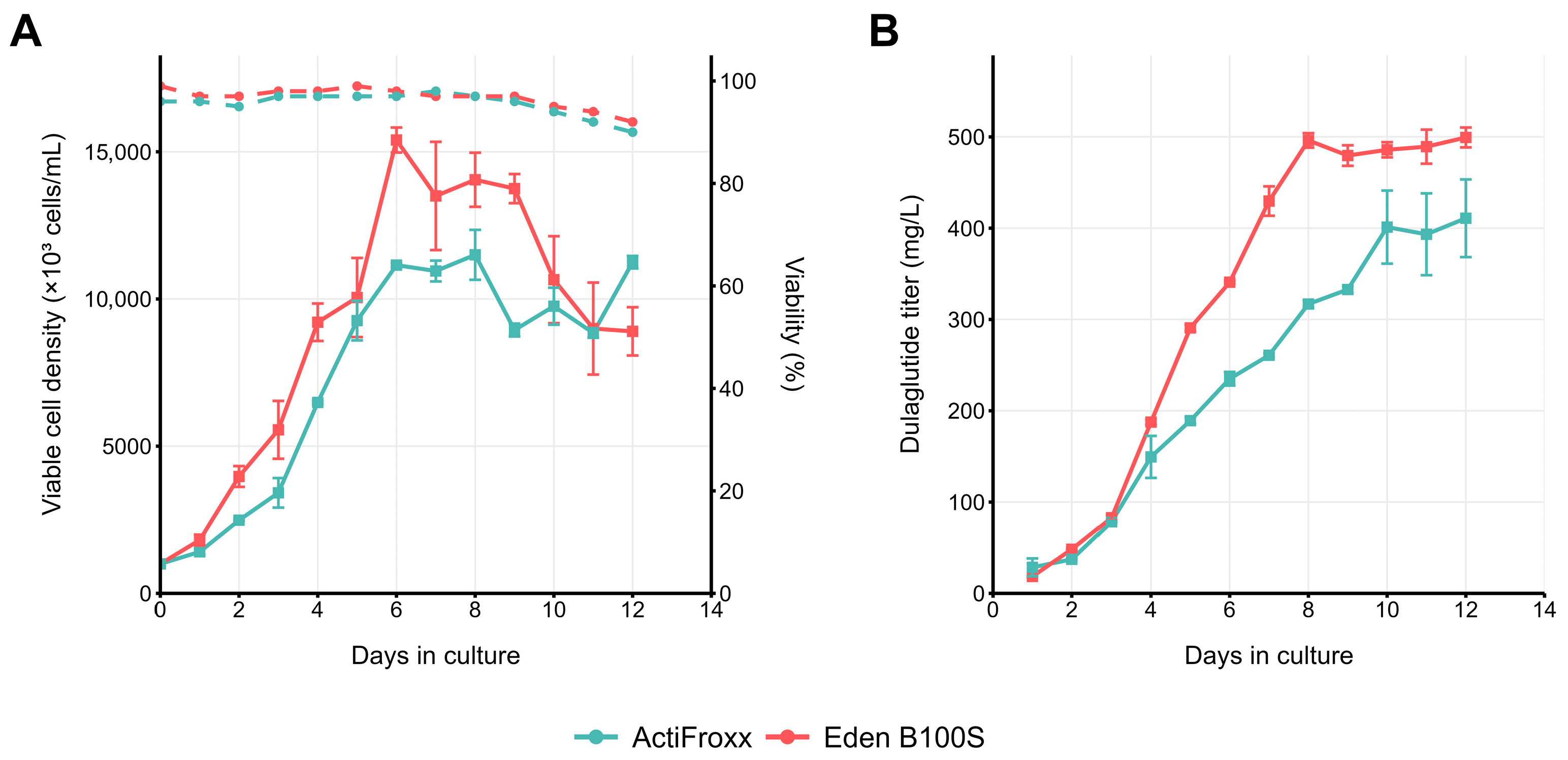

2.3. Pilot Fed-Batch Performance of the Dual-Selected Pool

2.4. Clonal Cell Lines Generation

2.5. Fed-Batch Culturing of Clonal Lines

2.6. Productivity Stability

2.7. Target Protein Quality and Bioactivity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Expression Vector Construction

4.2. Cell Culture and Transfection

4.3. Sequential Selection and Gene Amplification

4.4. Clone Isolation, Screening, and Upscaling

4.5. Fed-Batch Cultivation

4.5.1. Microbioreactor Experiments

4.5.2. Shake Flask Experiments

4.5.3. Process Monitoring and Sampling

4.6. Stability Studies

4.7. Dulaglutide Purification

4.8. Analytical Methods

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary |

| DHFR | Dihydrofolate reductase |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| MSX | Methionine sulfoximine |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| Fc | Fragment, crystallizable |

| qP | Specific productivity |

| VCD | Viable cell density |

| SEC-HPLC | Size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| IRES | Internal Ribosome Entry Site |

| EC50 | Half-Maximal Effective Concentration |

| EEF1A1 | Elongation factor 1-alpha 1 |

| EBVTRs | Epstein–Barr virus terminal repeats |

| HT | Hypoxanthine–thymidine |

| DPP-4 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 |

| GLP-1R | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor |

| CRE | cAMP response element |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| UPLC | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| WT | Wild type |

References

- Loh, W.J. Overview of diabetes agents in cardiovascular disease: It takes an orchestra to play Tchaikovsky in symphony. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2025, 32, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarti, H.N.; Kesavadev, J.; Kovil, R.; Sanyal, D.; Das, S.; Roy, N.; Kumar, D.; Deb, B.; Chaudhuri, S.R.; Aneja, P. Management of Hypertension, Obesity, Lipids, and Diabetes with Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists. Int. J. Diabetes Technol. 2024, 3, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentlein, R.; Gallwitz, B.; Schmidt, W.E. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 214, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaesner, W.; Vick, A.M.; Millican, R.; Ellis, B.; Tschang, S.H.; Tian, Y.; Bokvist, K.; Brenner, M.; Koester, A.; Porksen, N.; et al. Engineering and characterization of the long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue LY2189265, an Fc fusion protein. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2010, 26, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggio, L.L.; Huang, Q.; Brown, T.J.; Drucker, D.J. A recombinant human glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1-albumin protein (albugon) mimics peptidergic activation of GLP-1 receptor-dependent pathways coupled with satiety, gastrointestinal motility, and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 2004, 53, 2492–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assessment Report Trulicity International Non-Proprietary Name: Dulaglutide. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/trulicity-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kim, D.M.; Chu, S.H.; Kim, S.; Park, Y.W.; Kim, S.S. Fc fusion to glucagon-like peptide-1 inhibits degradation by human DPP-IV, increasing its half-life in serum and inducing a potent activity for human GLP-1 receptor activation. BMB Rep. 2009, 42, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xiao, H.-P.; Zhang, X.-Y. Expression and Characterization of Recombinant GLP-1-IgG4-Fc Fusion Protein. China Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, N.A.; Dayanova, L.K.; Gayamova, E.A.; Sinegubova, M.V.; Kovnir, S.V.; Vorobiev, I.I. Targeted Knockout of the dhfr, glul, bak1, and bax Genes by the Multiplex Genome Editing in CHO Cells. Doklady. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 502, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, N.A.; Sinegubova, M.V.; Kolesov, D.E.; Khodak, Y.A.; Tatarskiy, V.V.; Vorobiev, I.I. Genomic and Phenotypic Characterization of CHO 4BGD Cells with Quad Knockout and Overexpression of Two Housekeeping Genes That Allow for Metabolic Selection and Extended Fed-Batch Culturing. Cells 2025, 14, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, N.A.; Kovnir, S.V.; Hodak, J.A.; Vorobiev, I.I.; Gabibov, A.G.; Skryabin, K.G. Improved elongation factor-1 alpha-based vectors for stable high-level expression of heterologous proteins in Chinese hamster ovary cells. BMC Biotechnol. 2014, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, N.A.; Kovnir, S.V.; Gabibov, A.G.; Vorobiev, I.I. Stable high-level expression of factor VIII in Chinese hamster ovary cells in improved elongation factor-1 alpha-based system. BMC Biotechnol. 2017, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovnir, S.; Orlova, N.; Shakhparonov, M.; Skryabin, K.; Gabibov, A.; Vorobiev, I.I. A Highly Productive CHO Cell Line Secreting Human Blood Clotting Factor IX. Acta Naturae 2018, 10, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, N.A.; Kovnir, S.V.; Khodak, Y.A.; Polzikov, M.A.; Nikitina, V.A.; Skryabin, K.G.; Vorobiev, I.I. High-level expression of biologically active human follicle stimulating hormone in the Chinese hamster ovary cell line by a pair of tricistronic and monocistronic vectors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinegubova, M.V.; Orlova, N.A.; Vorobiev, I.I. Promoter from Chinese hamster elongation factor-1a gene and Epstein-Barr virus terminal repeats concatemer fragment maintain stable high-level expression of recombinant proteins. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinegubova, M.V.; Orlova, N.A.; Kovnir, S.V.; Dayanova, L.K.; Vorobiev, I.I. High-level expression of the monomeric SARS-CoV-2 S protein RBD 320-537 in stably transfected CHO cells by the EEF1A1-based plasmid vector. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0242890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesov, D.E.; Gaiamova, E.A.; Orlova, N.A.; Vorobiev, I.I. Dimeric ACE2-FC Is Equivalent to Monomeric ACE2 in the Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test. Biochemistry 2023, 88, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signal Peptide Database-Mammalia. Available online: http://www.signalpeptide.de/index.php?sess=&m=listspdb_mammalia&s=details&id=20579&listname= (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Torres, M.; Akhtar, S.; McKenzie, E.A.; Dickson, A.J. Temperature Down-Shift Modifies Expression of UPR-/ERAD-Related Genes and Enhances Production of a Chimeric Fusion Protein in CHO Cells. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, e2000081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wei, S.; Cao, C.; Chen, K.; He, H.; Gao, G. Retrovectors packaged in CHO cells to generate GLP-1-Fc stable expression CHO cell lines. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 41, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. GLP-1 Analog-Fc Fusion Protein, Its Preparation Method and Use. EP3029072A1, 19 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

| DUL | TRU | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | MW, Da | Relative Abundance | Number | MW, Da | Relative Abundance |

| 1 | 31,286.4645 | 55% | 1 | 31,286.3724 | 75% |

| 2 | 31,448.0186 | 14% | 2 | 31,448.4705 | 15% |

| 3 | 31,366.412 | 13% | - | - | - |

| 4 | 31,528.2998 | 7% | - | - | - |

| 5 | 31,609.9932 | 3% | 3 | 31,610.6656 | 3% |

| - | 4 | 31,140.7391 | 3% | ||

| 6 | 31,489.9405 | 3% | 5 | 31,488.6724 | 2% |

| 7 | 31,059.0143 | 2% | - | - | - |

| 8 | 31,083.534 | 1% | - | - | - |

| 9 | 31,759.2865 | 1% | - | - | - |

| 10 | 31,569.8966 | 1% | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | 6 | 31,377.2315 | 1% |

| - | - | - | 7 | 31,545.7189 | 1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaifutdinov, R.R.; Sinegubova, M.V.; Vorobiev, I.I.; Prokhorova, P.E.; Podkorytov, A.B.; Orlova, N.A. Production of a Dulaglutide Analogue by Apoptosis-Resistant Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in a 3-Week Fed-Batch Process. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121896

Shaifutdinov RR, Sinegubova MV, Vorobiev II, Prokhorova PE, Podkorytov AB, Orlova NA. Production of a Dulaglutide Analogue by Apoptosis-Resistant Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in a 3-Week Fed-Batch Process. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121896

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaifutdinov, Rolan R., Maria V. Sinegubova, Ivan I. Vorobiev, Polina E. Prokhorova, Alexey B. Podkorytov, and Nadezhda A. Orlova. 2025. "Production of a Dulaglutide Analogue by Apoptosis-Resistant Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in a 3-Week Fed-Batch Process" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121896

APA StyleShaifutdinov, R. R., Sinegubova, M. V., Vorobiev, I. I., Prokhorova, P. E., Podkorytov, A. B., & Orlova, N. A. (2025). Production of a Dulaglutide Analogue by Apoptosis-Resistant Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells in a 3-Week Fed-Batch Process. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121896