Pine-Extracted Phytosterol β-Sitosterol (APOPROSTAT® Forte) Inhibits Both Human Prostate Smooth Muscle Contraction and Prostate Stromal Cell Growth, Without Cytotoxic Effects: A Mechanistic Link to Clinical Efficacy in LUTS/BPH

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

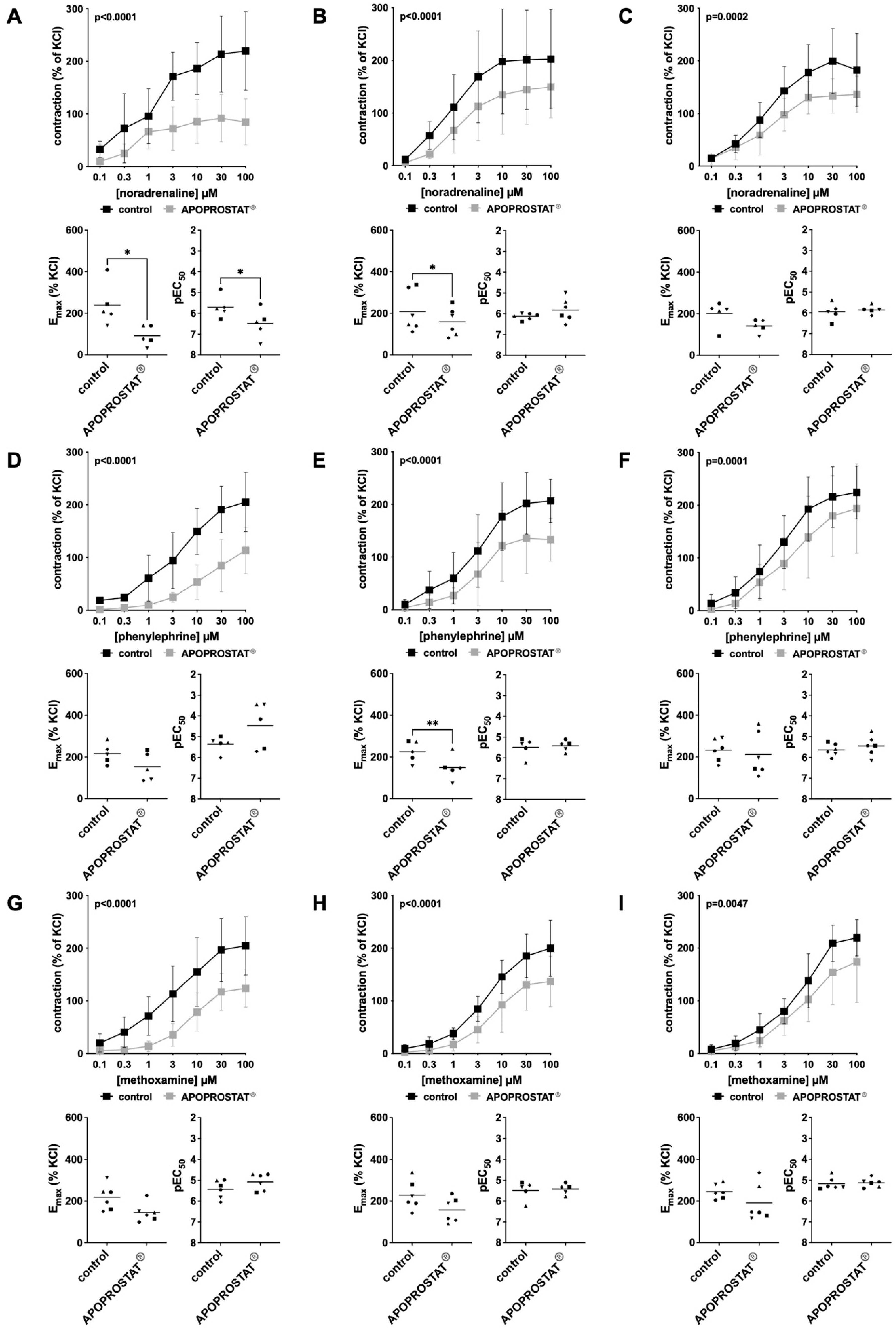

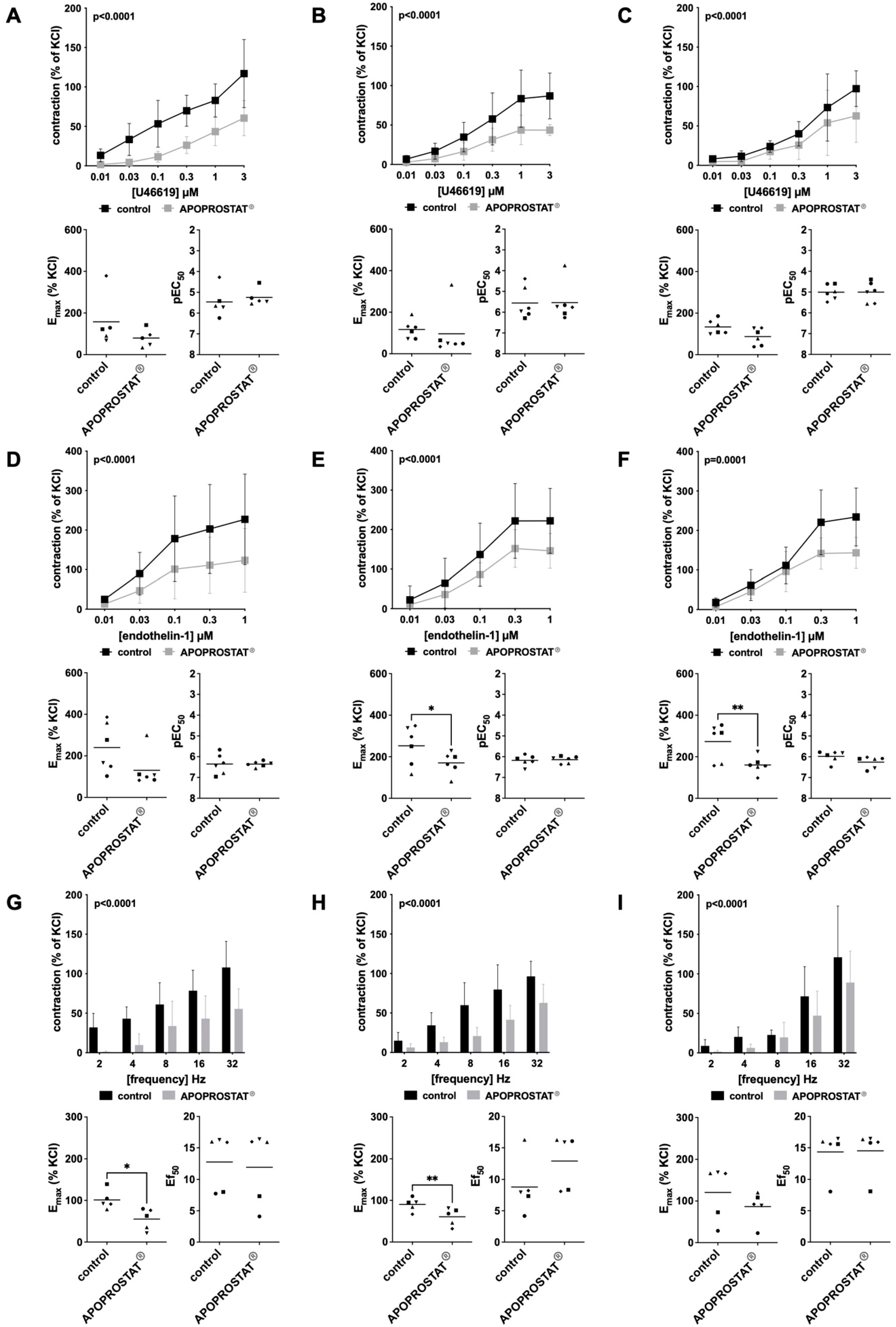

2.1. Contractility Measurements

2.1.1. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Adrenergic Contractions of Human Prostate Tissues

2.1.2. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Non-Adrenergic Contractions of Human Prostate Tissues

2.1.3. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Neurogenic Contractions of Human Prostate Tissues

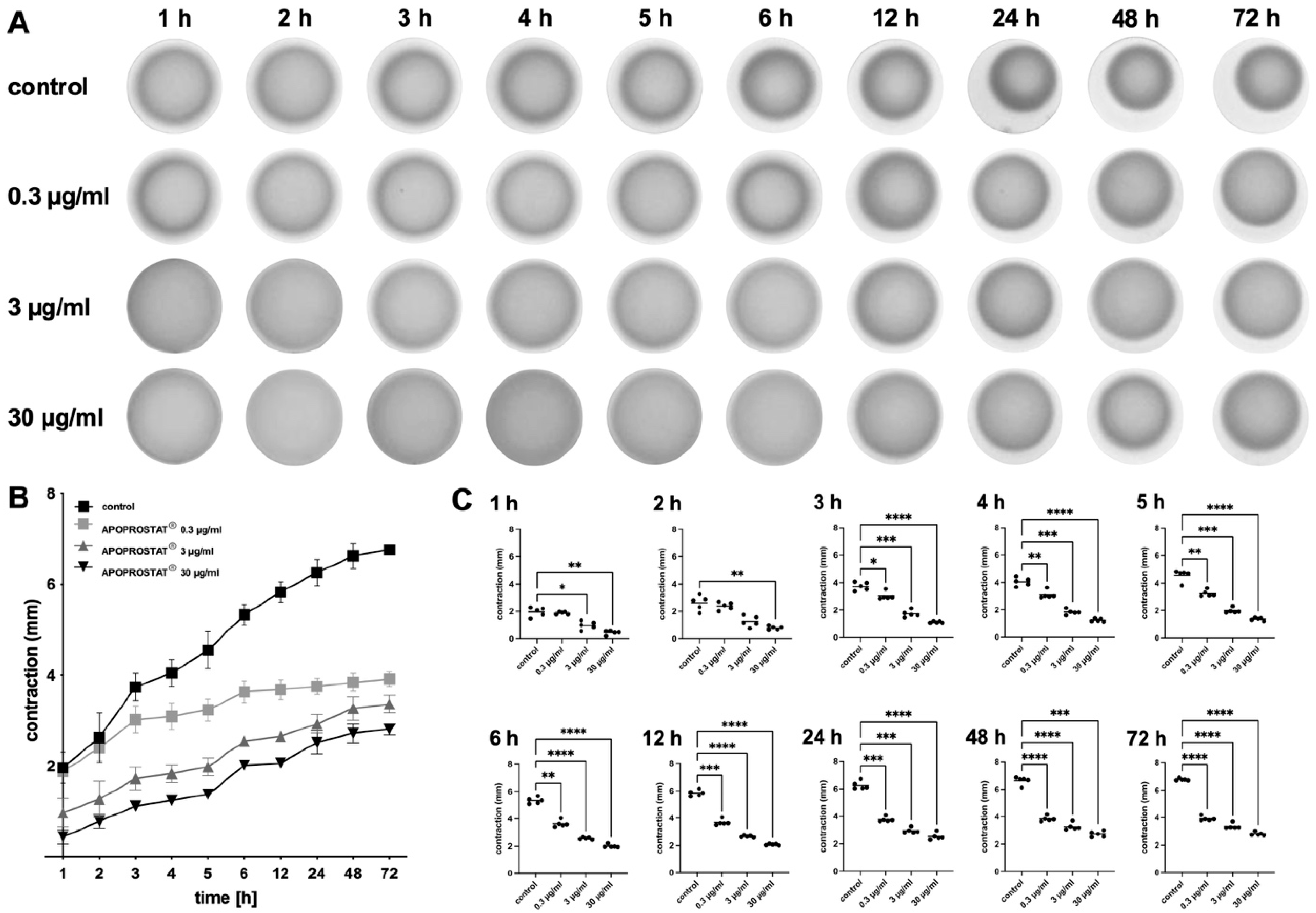

2.1.4. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on the Contractility of WPMY-1 Cells

2.2. Cell Culture Studies

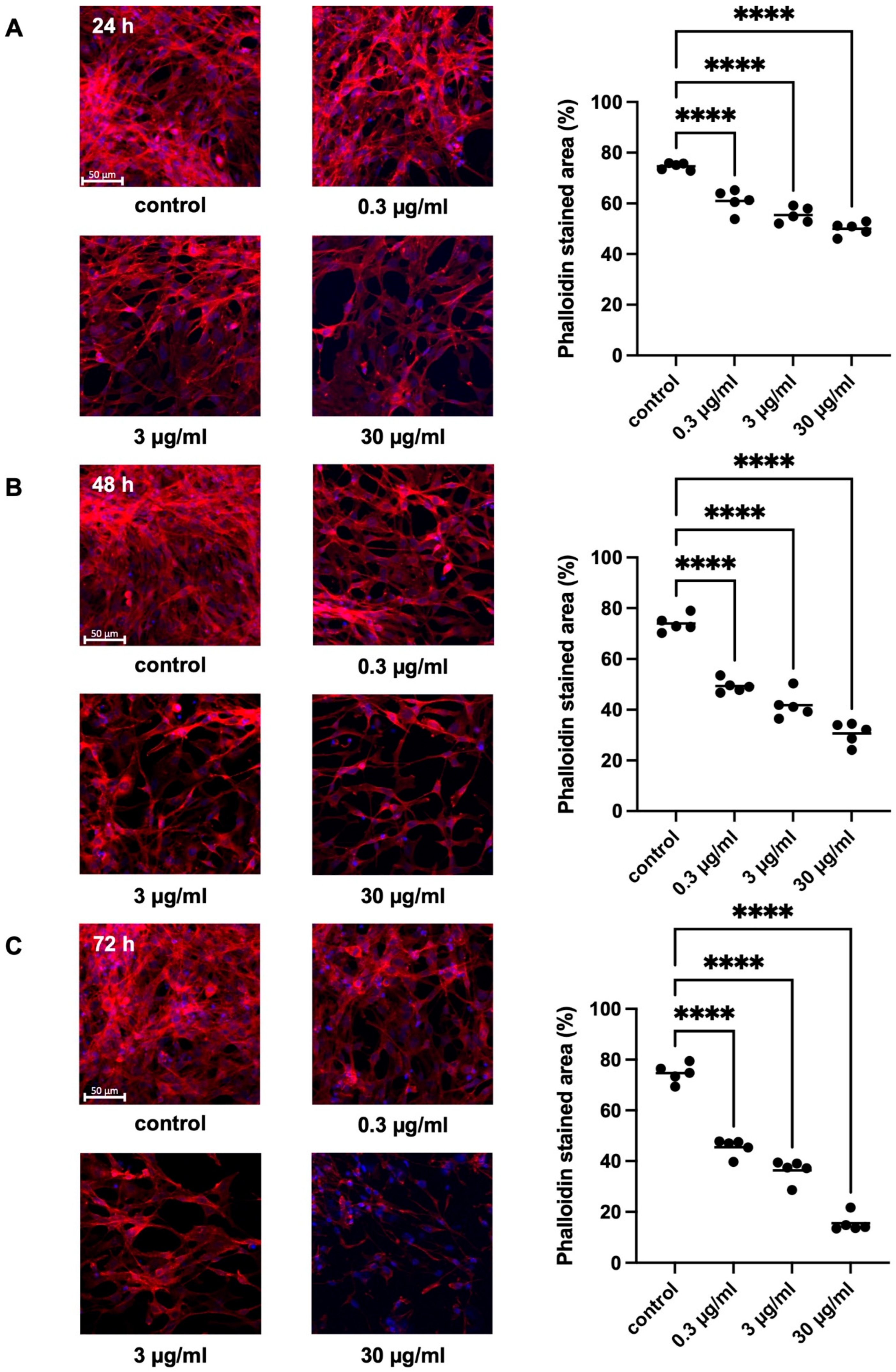

2.2.1. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Actin Organization of WPMY-1 Cells

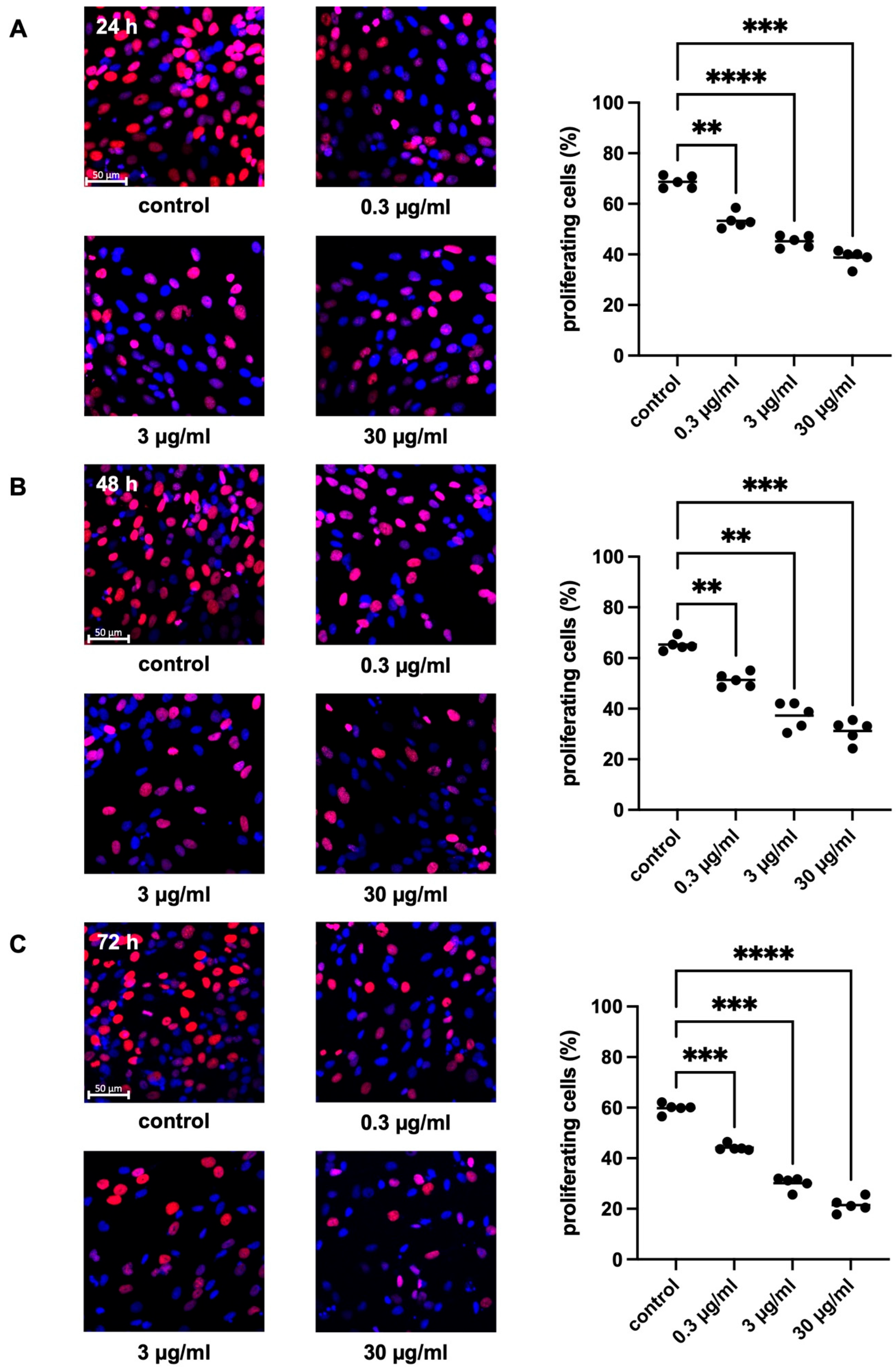

2.2.2. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Proliferation of WPMY-1 Cells

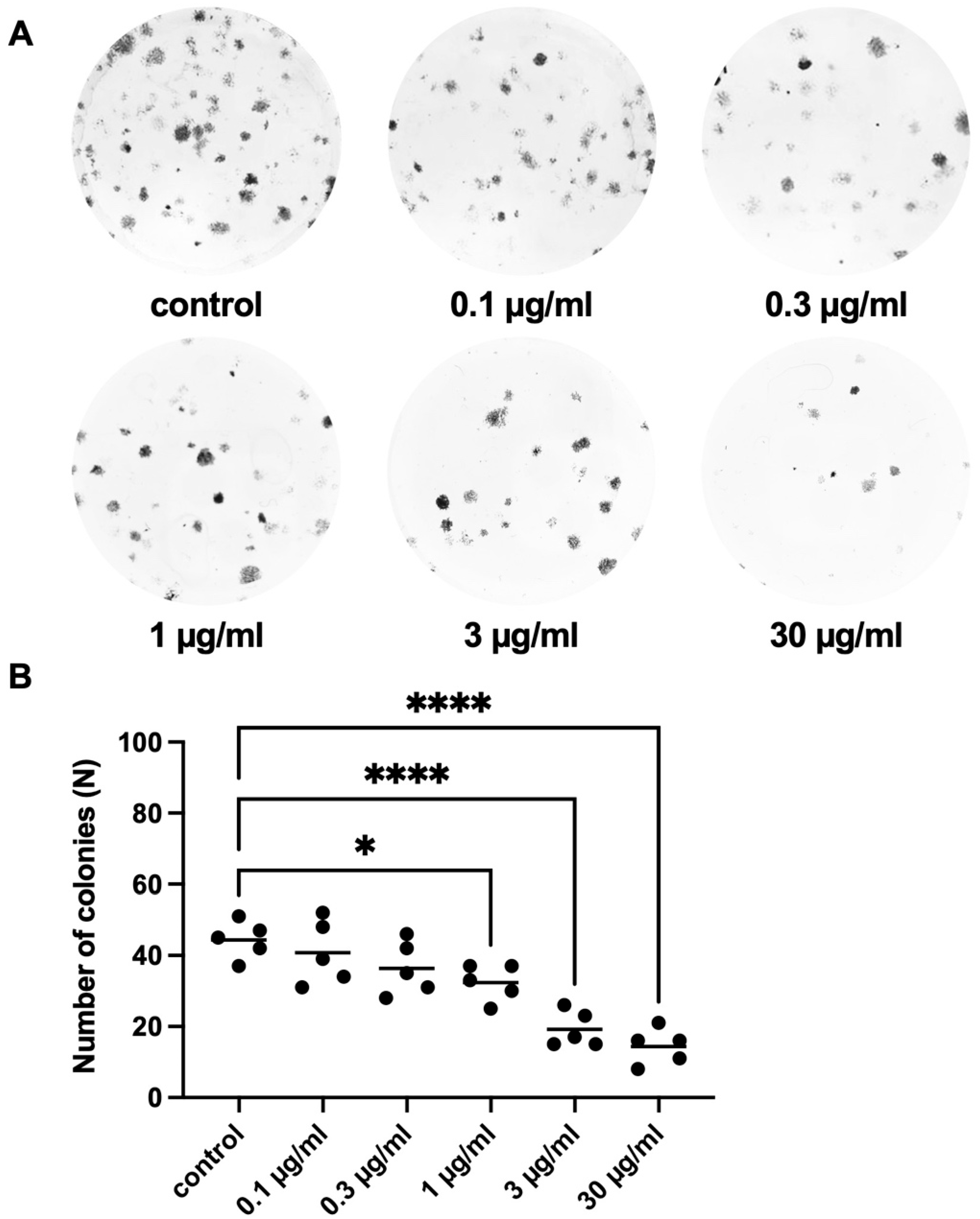

2.2.3. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Colony Formation of WPMY-1 Cells

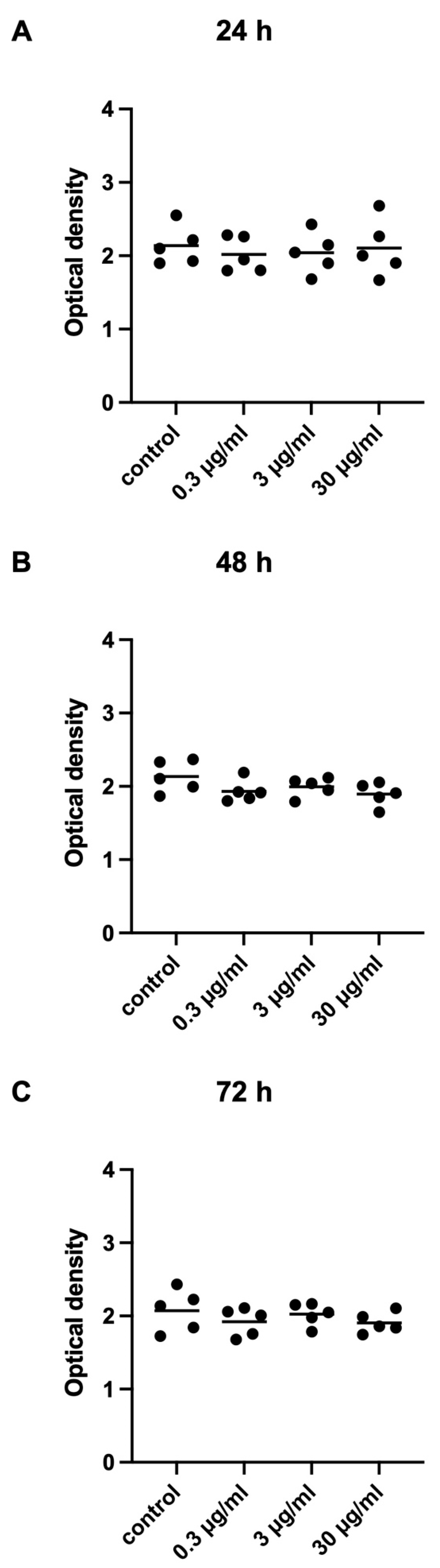

2.2.4. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Viability of WPMY-1 Cells

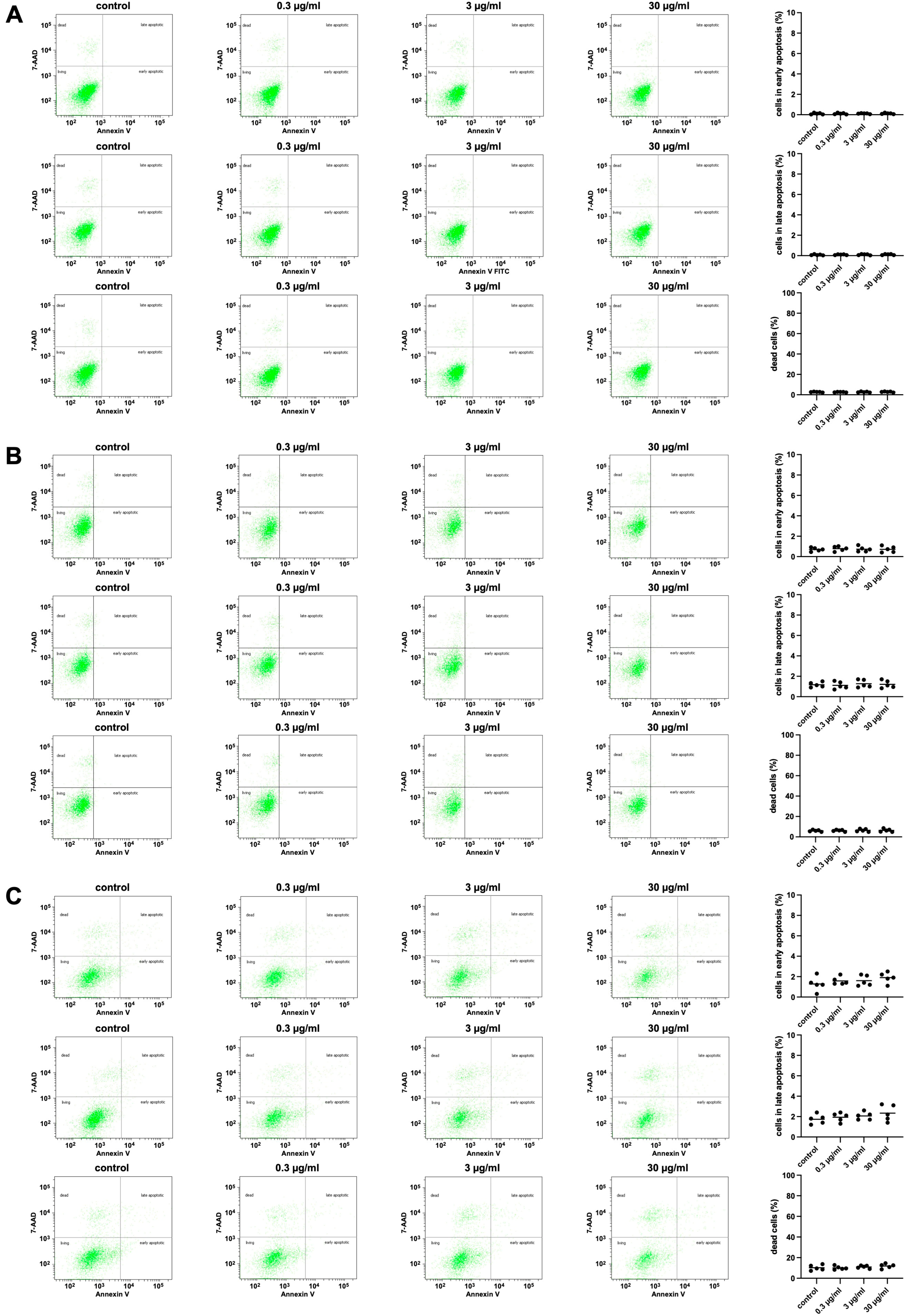

2.2.5. Effects of APOPROSTAT® Forte on Apoptosis and Cell Death of WPMY-1 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials, Drugs, and Nomenclature

4.2. Preparation of APOPROSTAT® Forte

4.3. Organ Bath

4.4. Cell Culture

4.4.1. Cell Contraction Assay

4.4.2. Phalloidin Staining

4.4.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.4.4. Plate Colony Assay

4.4.5. Cell Viability Assay

4.4.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis for Apoptosis and Cell Death

4.5. Data and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-AR | 5α-reductase |

| 5-ARI | 5α-reductase inhibitor |

| 7-AAD | 7-aminoactinomycin D |

| APC | allophycocyanin |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BPH | benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| CCK-8 | cell counting kit 8 |

| DHT | dihydrotestosterone |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| EdU | 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine |

| ETA | endothelin receptor A |

| ETB | endothelin receptor B |

| FCS | fetal calf serum |

| HeSr | hexane-extracted Serenoa repens |

| LUTS | lower urinary tract symptoms |

| OAB | overactive bladder |

| OD | optical density |

| OTC | over the counter |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| WPMY-1 | immortalized human prostate stromal cell line (benign) |

References

- Roehrborn, C.G. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: An overview. Rev. Urol. 2005, 7 (Suppl. S9), S3–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Gravas, S.; Cornu, J.N.; Gacci, M.; Gratzke, C.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Mamoulakis, C.; Rieken, M.; Speakman, M.J.; Tikkinen, K.A.O. Management of Non-Neurogenic Male LUTS. EAU Guidelines; Edn. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan; European Association of Urology: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-94-92671-13-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chapple, C. Overview on the lower urinary tract. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepor, H. Pathophysiology, epidemiology, and natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev. Urol. 2004, 6 (Suppl. S9), S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roehrborn, C.G. Pathology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2008, 20 (Suppl. S3), S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeb, S.; Kettermann, A.; Carter, H.B.; Ferrucci, L.; Metter, E.J.; Walsh, P.C. Prostate volume changes over time: Results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 1458–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Kopp, Z.S.; Agatep, B.; Milsom, I.; Abrams, P. Worldwide prevalence estimates of lower urinary tract symptoms, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence and bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1132–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazala, S.; Tul, Y.; Wagg, A.; Widder, S.L.; Khadaroo, R.G.; Acute Care and Emergency Surgery (ACES) Group. Quality of life and long-term outcomes of octo- and nonagenarians following acute care surgery: A cross sectional study. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2013, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebell, P.J.; El-Khadra, S.; Horstmann, M.; Kollenbach, P.; Ludecke, G.; Quack, T.; Rug, M.; Stephan-Odenthal, M.; Bode-Greuel, K.; Zink, S.; et al. What do urologist do in daily practice? A first “unfiltered” look at patient care. Urol. A 2021, 60, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennenberg, M.; Stief, C.G.; Gratzke, C. Prostatic alpha1-adrenoceptors: New concepts of function, regulation, and intracellular signaling. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2014, 33, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oelke, M.; Gericke, A.; Michel, M.C. Cardiovascular and ocular safety of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in the treatment of male lower urinary tract symptoms. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindolo, L.; Pirozzi, L.; Fanizza, C.; Romero, M.; Tubaro, A.; Autorino, R.; De Nunzio, C.; Schips, L. Drug Adherence and Clinical Outcomes for Patients Under Pharmacological Therapy for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Related to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Population-based Cohort Study. Eur. Urol. 2014, 68, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksym, R.B.; Kajdy, A.; Rabijewski, M. Post-finasteride syndrome—Does it really exist? Aging Male 2019, 22, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, C.C.; Notte, S.M.; Maroulis, C.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Cardozo, L.; Subramanian, D.; Coyne, K.S. Persistence and adherence in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome with anticholinergic therapy: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2011, 65, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novara, G.; Giannarini, G.; Alcaraz, A.; Cozar-Olmo, J.M.; Descazeaud, A.; Montorsi, F.; Ficarra, V. Efficacy and Safety of Hexanic Lipidosterolic Extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon) in the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Due to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. Urol. Focus 2016, 2, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela-Navarrete, R.; Alcaraz, A.; Rodríguez-Antolín, A.; Minana Lopez, B.; Fernández-Gómez, J.M.; Angulo, J.C.; Castro Diaz, D.; Romero-Otero, J.; Brenes, F.J.; Carballido, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a hexanic extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon(R)) for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH): Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BJU Int. 2018, 122, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Paktiaval, R.; Lenau, P.; Stadelmeier, L.F.; Buchner, A.; Kolben, T.; Magistro, G.; Stief, C.G.; Hennenberg, M. Phytomedicines in Pharmacotherapy of LUTS/BPH—What Do Patients Think? Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 2507–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Buchner, A.; Hennenberg, M.; Stadelmeier, L.F.; Höhn, H.; Vilsmaier, T.; Mumm, M.L.; Kolben, T.; Stief, C.G.; Mumm, J.N. Choosing a Specialist: An Explanatory Study of Factors Influencing Patients in Choosing a Urologist. Urol. Int. 2021, 105, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Benard, P.; Cousse, H.; Bengone, T. Distribution study of radioactivity in rats after oral administration of the lipido/sterolic extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon®) supplemented with [1-14C]-lauric acid, [1-14C]-oleic acid or [4-14C]-β-sitosterol. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 1997, 22, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, M.; Garcia de Boto, M.J.; Cantabrana, B.; Hidalgo, A. Mechanisms involved in the spasmolytic effect of extracts from Sabal serrulata fruit on smooth muscle. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996, 27, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, T.; Eise, N.T.; Simpson, J.S.; Ventura, S. Pharmacological characterization and chemical fractionation of a liposterolic extract of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens): Effects on rat prostate contractility. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 152, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepel, M.; Dinh, L.; Mitchell, A.; Schafers, R.F.; Rubben, H.; Michel, M.C. Do saw palmetto extracts block human alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes in vivo? Prostate 2001, 46, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madersbacher, S.; Berger, I.; Ponholzer, A.; Marszalek, M. Plant extracts: Sense or nonsense? Curr. Opin. Urol. 2008, 18, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Wendt, A.; Springer, F.; Vigodski, V.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Wang, R.; Huang, R.; Liu, Y.; Schulz, H.; et al. Permixon®, hexane-extracted Serenoa repens, inhibits human prostate and bladder smooth muscle contraction and exerts growth-related functions in human prostate stromal cells. Life Sci. 2022, 308, 120931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penugonda, K.; Lindshield, B.L. Fatty acid and phytosterol content of commercial saw palmetto supplements. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3617–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macoska, J.A. The use of beta-sitosterol for the treatment of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2023, 11, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klippel, K.F.; Hiltl, D.M.; Schipp, B. A multicentric, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of beta-sitosterol (phytosterol) for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. German BPH-Phyto Study group. Br. J. Urol. 1997, 80, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Jurincic-Winkler, C.D.; Klippel, K.F. Konservative Therapie der benignen Prostatahyperplasie mit hochdosiertem ß-Sitosterin (65 mg). UROSCOP 1993, 1/93, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Berges, R.R.; Windeler, J.; Trampisch, H.J.; Senge, T. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of beta-sitosterol in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Beta-sitosterol Study Group. Lancet 1995, 345, 1529–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, F.K.; Wyllie, M.G. Not all brands are created equal: A comparison of selected components of different brands of Serenoa repens extract. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2004, 7, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buț, M.G.; Jîtcă, G.; Imre, S.; Vari, C.E.; Ősz, B.E.; Jîtcă, C.M.; Tero-Vescan, A. The Lack of Standardization and Pharmacological Effect Limits the Potential Clinical Usefulness of Phytosterols in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Plants 2023, 12, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, T.J.; MacDonald, R.; Ishani, A. beta-sitosterol for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review. BJU Int. 1999, 83, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touriño, S.; Selga, A.; Jiménez, A.; Juliá, L.; Lozano, C.; Lizárraga, D.; Cascante, M.; Torres, J.L. Procyanidin fractions from pine (Pinus pinaster) bark: Radical scavenging power in solution, antioxidant activity in emulsion, and antiproliferative effect in melanoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4728–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Allkanjari, O.; Vitalone, A.; Busetto, G.M.; Cai, T.; Larganà, G.; Russo, G.I.; Magri, V.; Perletti, G.; Della Cuna, F.S.R.; et al. Nutraceutical treatment and prevention of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2019, 91, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennenberg, M.; Acevedo, A.; Wiemer, N.; Kan, A.; Tamalunas, A.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Rutz, B.; Ciotkowska, A.; Herlemann, A.; et al. Non-Adrenergic, Tamsulosin-Insensitive Smooth Muscle Contraction is Sufficient to Replace alpha1-Adrenergic Tension in the Human Prostate. Prostate 2017, 77, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- But, M.G.; Tero-Vescan, A.; Puscas, A.; Jitca, G.; Marc, G. Exploring the Inhibitory Potential of Phytosterols beta-Sitosterol, Stigmasterol, and Campesterol on 5-Alpha Reductase Activity in the Human Prostate: An In Vitro and In Silico Approach. Plants 2024, 13, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madalina-Georgiana, B.; Imre, S.; Vari, C.; Osz, B.E.; Stefanescu, R.; Puscas, A.; Jitca, G.; Matei, C.M.; Tero-Vescan, A. Assessing beta-Sitosterol Levels in Dietary Supplements for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Implications for Therapeutic Efficacy. Cureus 2024, 16, e60309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudeep, H.V.; Venkatakrishna, K.; Amrutharaj, B.; Anitha; Shyamprasad, K. A phytosterol-enriched saw palmetto supercritical CO2 extract ameliorates testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia by regulating the inflammatory and apoptotic proteins in a rat model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.; Li, B.; Rutz, B.; Ciotkowska, A.; Huang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Strittmatter, F.; Waidelich, R.; Stief, C.G.; et al. Purinergic smooth muscle contractions in the human prostate: Estimation of relevance and characterization of different agonists. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2021, 394, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlemann, A.; Keller, P.; Schott, M.; Tamalunas, A.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Waidelich, R.; Strittmatter, F.; et al. Inhibition of smooth muscle contraction and ARF6 activity by the inhibitor for cytohesin GEFs, secinH3, in the human prostate. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2018, 314, F47–F57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Erlander, M.G.; Ridinger, M.; Wang, R.; Tamalunas, A.; Waidelich, R.; Stief, C.G.; et al. Onvansertib, a polo-like kinase 1 inhibitor, inhibits prostate stromal cell growth and prostate smooth muscle contraction, which is additive to inhibition by alpha1-blockers. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 873, 172985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Crespo, F.J.; Aragón-Gastélum, J.L.; Gutiérrez-Alcántara, E.J.; Zamora-Crescencio, P.; Gómez-Galicia, D.L.; Alatriste-Kurzel, D.R.; Alvarez, G.; Hernández-Núñez, E. β-Sitosterol Mediates Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle Relaxation Induced by Coccoloba uvifera via Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subtype 3. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Z.Y.; Wong, S.L.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.T.; Lau, C.W.; Lee, H.K.; Huang, Y.; Tsang, S.Y. β-Sitosterol oxidation products attenuate vasorelaxation by increasing reactive oxygen species and cyclooxygenase-2. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 97, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promprom, W.; Kupittayanant, P.; Indrapichate, K.; Wray, S.; Kupittayanant, S. The effects of pomegranate seed extract and beta-sitosterol on rat uterine contractions. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Meng, Z.Y.; Wen, H.; Lu, C.H.; Qin, Y.; Xie, Y.M.; Chen, Q.; Lv, J.H.; Huang, F.; Zeng, Z.Y. beta-sitosterol alleviates pulmonary arterial hypertension by altering smooth muscle cell phenotype and DNA damage/cGAS/STING signaling. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berges, R.R.; Kassen, A.; Senge, T. Treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia with beta-sitosterol: An 18-month follow-up. BJU Int. 2000, 85, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.J.; Williford, W.O.; Chang, Y.; Machi, M.; Jones, K.M.; Walker-Corkery, E.; Lepor, H. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: How much change in the American Urological Association symptom index and the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index is perceptible to patients? J. Urol. 1995, 154, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, J.D.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Bautista, O.M.; Andriole, G.L., Jr.; Dixon, C.M.; Kusek, J.W.; Lepor, H.; McVary, K.T.; Nyberg, L.M., Jr.; Clarke, H.S.; et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2387–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrborn, C.G.; Siami, P.; Barkin, J.; Damiao, R.; Major-Walker, K.; Nandy, I.; Morrill, B.B.; Gagnier, R.P.; Montorsi, F.; CombAT Study Group. The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study. Eur. Urol. 2010, 57, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaraz, A.; Rodriguez-Antolin, A.; Carballido-Rodriguez, J.; Castro-Diaz, D.; Medina-Polo, J.; Fernandez-Gomez, J.M.; Ficarra, V.; Palou, J.; de Leon Roca, J.P.; Angulo, J.C.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the hexanic extract of Serenoa repens compared to tamsulosin in moderate-severe LUTS-BPH patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, C.; Terraza, A.; Devillier, C.; Carilla, E.; Briley, M.; Loire, C.; Descomps, B. Inhibition of androgen metabolism and binding by a liposterolic extract of “Serenoa repens B” in human foreskin fibroblasts. J. Steroid Biochem. 1984, 20, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, C.W.; Donnelly, F.; Ross, M.; Habib, F.K. Serenoa repens (Permixon): A 5alpha-reductase types I and II inhibitor-new evidence in a coculture model of BPH. Prostate 1999, 40, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savory, J.G.; May, D.; Reich, T.; La Casse, E.C.; Lakins, J.; Tenniswood, M.; Raymond, Y.; Hache, R.J.; Sikorska, M.; Lefebvre, Y.A. 5 alpha-Reductase type 1 is localized to the outer nuclear membrane. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1995, 110, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, N.S.; Habib, F.K. Partial purification of human prostatic 5 alpha-reductase (3-oxo-5 alpha-steroid:NADP+ 4-ene-oxido-reductase; EC 1.3.1.22) in a stable and active form. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1991, 38, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naslund, M.J.; Miner, M. A review of the clinical efficacy and safety of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors for the enlarged prostate. Clin. Ther. 2007, 29, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, N.; Bickett, K.; French, N.; Marcovici, G. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of botanically derived inhibitors of 5-alpha-reductase in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2002, 8, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, M.; Bratoeff, E.; Heuze, I.; Ramirez, E.; Sanchez, M.; Flores, E. Effect of beta-sitosterol as inhibitor of 5 alpha-reductase in hamster prostate. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 2003, 46, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, Z.; Nath, N.; Rauf, A.; Emran, T.B.; Mitra, S.; Islam, F.; Chandran, D.; Barua, J.; Khandaker, M.U.; Idris, A.M.; et al. Multifunctional roles and pharmacological potential of beta-sitosterol: Emerging evidence toward clinical applications. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 365, 110117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, L. Molecular Mechanism of beta-Sitosterol and its Derivatives in Tumor Progression. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 926975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, C.; Tenca, G.; Deguercy, A.; Troplin, P.; Poelman, D. In-vitro effects of polyphenols from cocoa and beta-sitosterol on the growth of human prostate cancer and normal cells. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 15, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassen, A.; Berges, R.; Senge, T. Effect of beta-sitosterol on transforming growth factor-beta-1 expression and translocation protein kinase C alpha in human prostate stromal cells in vitro. Eur. Urol. 2000, 37, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, H.L.; Yang, E.Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. TGF-beta stimulation and inhibition of cell proliferation: New mechanistic insights. Cell 1990, 63, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, N.; Untergasser, G.; Plas, E.; Berger, P. The ageing male reproductive tract. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salm, S.N.; Burger, P.E.; Coetzee, S.; Goto, K.; Moscatelli, D.; Wilson, E.L. TGF-β maintains dormancy of prostatic stem cells in the proximal region of ducts. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, A.C. Is there a scientific basis for the therapeutic effects of serenoa repens in benign prostatic hyperplasia? Mechanisms of action. J. Urol. 2004, 172 Pt 1, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paubert-Braquet, M.; Cousse, H.; Raynaud, J.P.; Mencia-Huerta, J.M.; Braquet, P. Effect of the lipidosterolic extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon) and its major components on basic fibroblast growth factor-induced proliferation of cultures of human prostate biopsies. Eur. Urol. 1998, 33, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengstler, J.G.; Sjogren, A.K.; Zink, D.; Hornberg, J.J. In vitro prediction of organ toxicity: The challenges of scaling and secondary mechanisms of toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Sauckel, C.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Wang, R.; Huang, R.; Li, B.; Stief, C.G.; Gratzke, C.; Hennenberg, M. Lenalidomide and pomalidomide inhibit growth of prostate stromal cells and human prostate smooth muscle contraction. Life Sci. 2021, 281, 119771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Wendt, A.; Springer, F.; Vigodski, V.; Trieb, F.; Eitelberger, N.; Poth, H.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Hu, S.; et al. Inhibition of Human Prostate and Bladder Smooth Muscle Contraction, Vasoconstriction of Porcine Renal and Coronary Arteries, and Growth-Related Functions of Prostate Stromal Cells by Presumed Small Molecule Gαq/11 Inhibitor, YM-254890. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 884057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamalunas, A.; Wendt, A.; Springer, F.; Vigodski, V.; Trieb, M.; Eitelberger, N. Immunomodulatory imide drugs inhibit human detrusor smooth muscle contraction and growth of human detrusor smooth muscle cells, and exhibit vaso-regulatory functions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, R.; Wang, R.; Tamalunas, A.; Waidelich, R.; Stief, C.G.; Hennenberg, M. Isoform-independent promotion of contractility and proliferation, and suppression of survival by with no lysine/K kinases in prostate stromal cells. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, K.; Kirsch, J.; Radbruch, A.; Chang, H.D.; Kaiser, T. Cell population identification using fluorescence-minus-one controls with a one-class classifying algorithm. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3372–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.C.; Murphy, T.J.; Motulsky, H.J. New Author Guidelines for Displaying Data and Reporting Data Analysis and Statistical Methods in Experimental Biology. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 97, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, M.J.; Alexander, S.; Cirino, G.; Docherty, J.R.; George, C.H.; Giembycz, M.A.; Hoyer, D.; Insel, P.A.; Izzo, A.A.; Ji, Y.; et al. Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: Updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tamalunas, A.; Schierholz, F.; Poth, H.; Vigodski, V.; Brandstetter, M.; Ciotkowska, A.; Rutz, B.; Hu, S.; Stadelmeier, L.F.; Schulz, H.; et al. Pine-Extracted Phytosterol β-Sitosterol (APOPROSTAT® Forte) Inhibits Both Human Prostate Smooth Muscle Contraction and Prostate Stromal Cell Growth, Without Cytotoxic Effects: A Mechanistic Link to Clinical Efficacy in LUTS/BPH. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121864

Tamalunas A, Schierholz F, Poth H, Vigodski V, Brandstetter M, Ciotkowska A, Rutz B, Hu S, Stadelmeier LF, Schulz H, et al. Pine-Extracted Phytosterol β-Sitosterol (APOPROSTAT® Forte) Inhibits Both Human Prostate Smooth Muscle Contraction and Prostate Stromal Cell Growth, Without Cytotoxic Effects: A Mechanistic Link to Clinical Efficacy in LUTS/BPH. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121864

Chicago/Turabian StyleTamalunas, Alexander, Felix Schierholz, Henrik Poth, Victor Vigodski, Michael Brandstetter, Anna Ciotkowska, Beata Rutz, Sheng Hu, Leo Federico Stadelmeier, Heiko Schulz, and et al. 2025. "Pine-Extracted Phytosterol β-Sitosterol (APOPROSTAT® Forte) Inhibits Both Human Prostate Smooth Muscle Contraction and Prostate Stromal Cell Growth, Without Cytotoxic Effects: A Mechanistic Link to Clinical Efficacy in LUTS/BPH" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121864

APA StyleTamalunas, A., Schierholz, F., Poth, H., Vigodski, V., Brandstetter, M., Ciotkowska, A., Rutz, B., Hu, S., Stadelmeier, L. F., Schulz, H., Ledderose, S., Rogenhofer, N., Kolben, T., Stief, C. G., & Hennenberg, M. (2025). Pine-Extracted Phytosterol β-Sitosterol (APOPROSTAT® Forte) Inhibits Both Human Prostate Smooth Muscle Contraction and Prostate Stromal Cell Growth, Without Cytotoxic Effects: A Mechanistic Link to Clinical Efficacy in LUTS/BPH. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121864