Understanding the Role of Polyols and Sugars in Reducing Aggregation in IgG2 and IgG4 Monoclonal Antibodies During Low-pH Viral Inactivation Step

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of pH on the Stability of Pembrolimumab (PEM) and Denosumab (DENO)

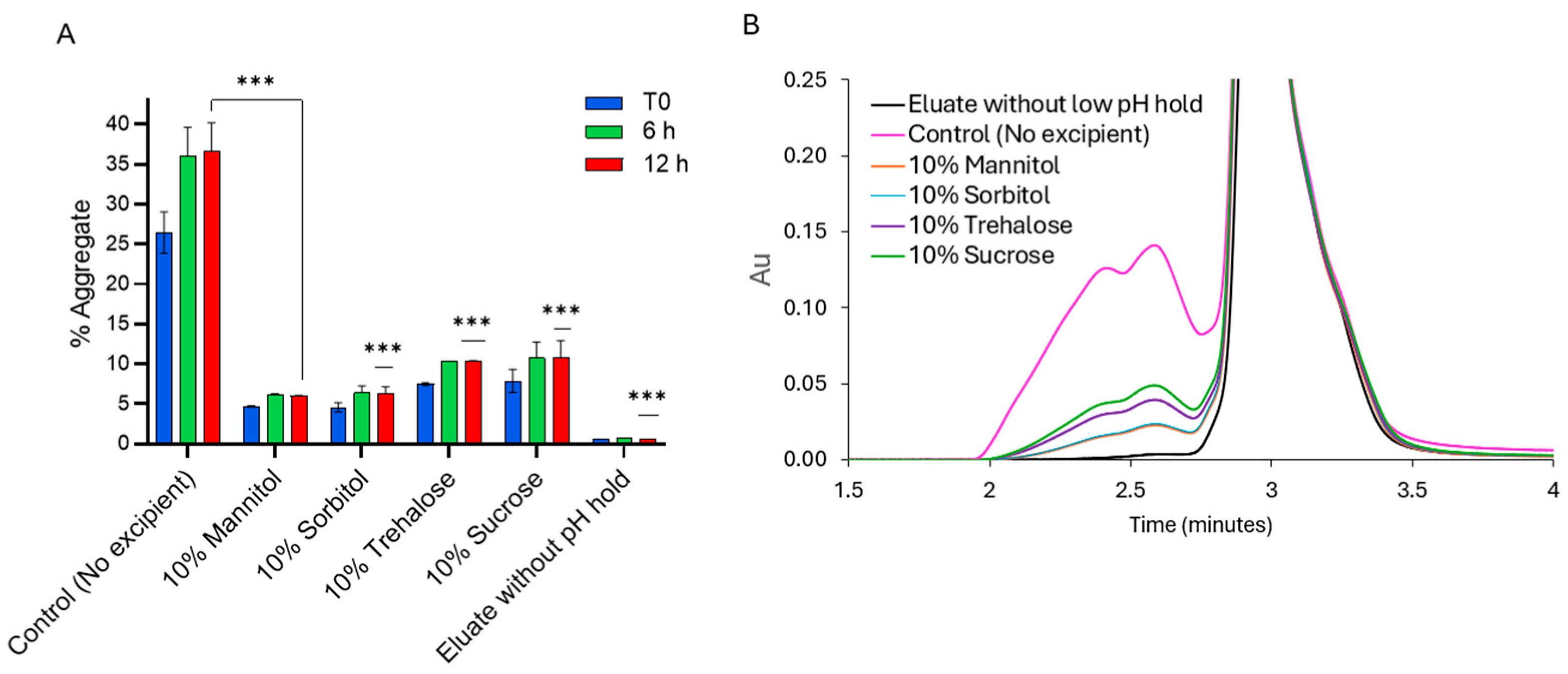

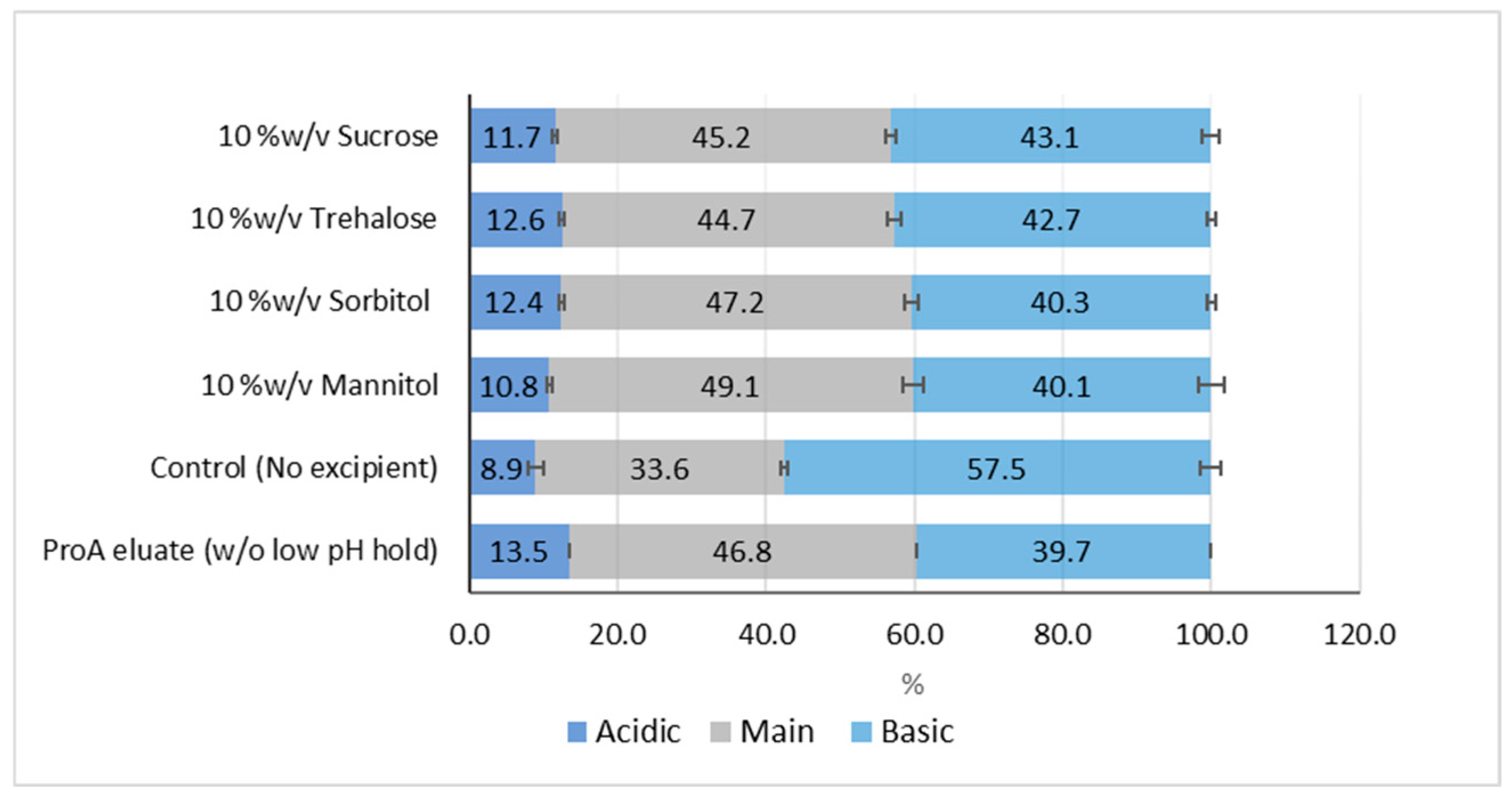

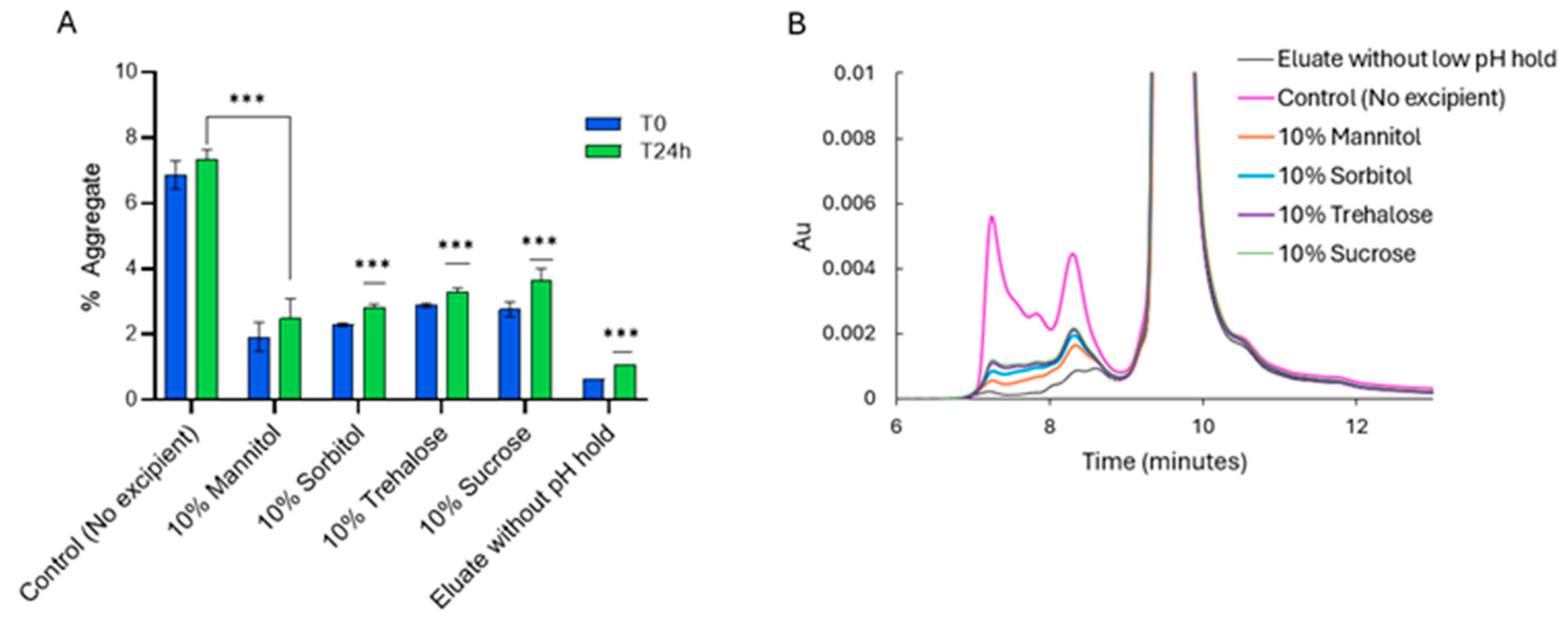

2.2. Effect of Additives on the Stability of PEM During Low-pH VI Operation

Aggregation and Charge Variant Profiles

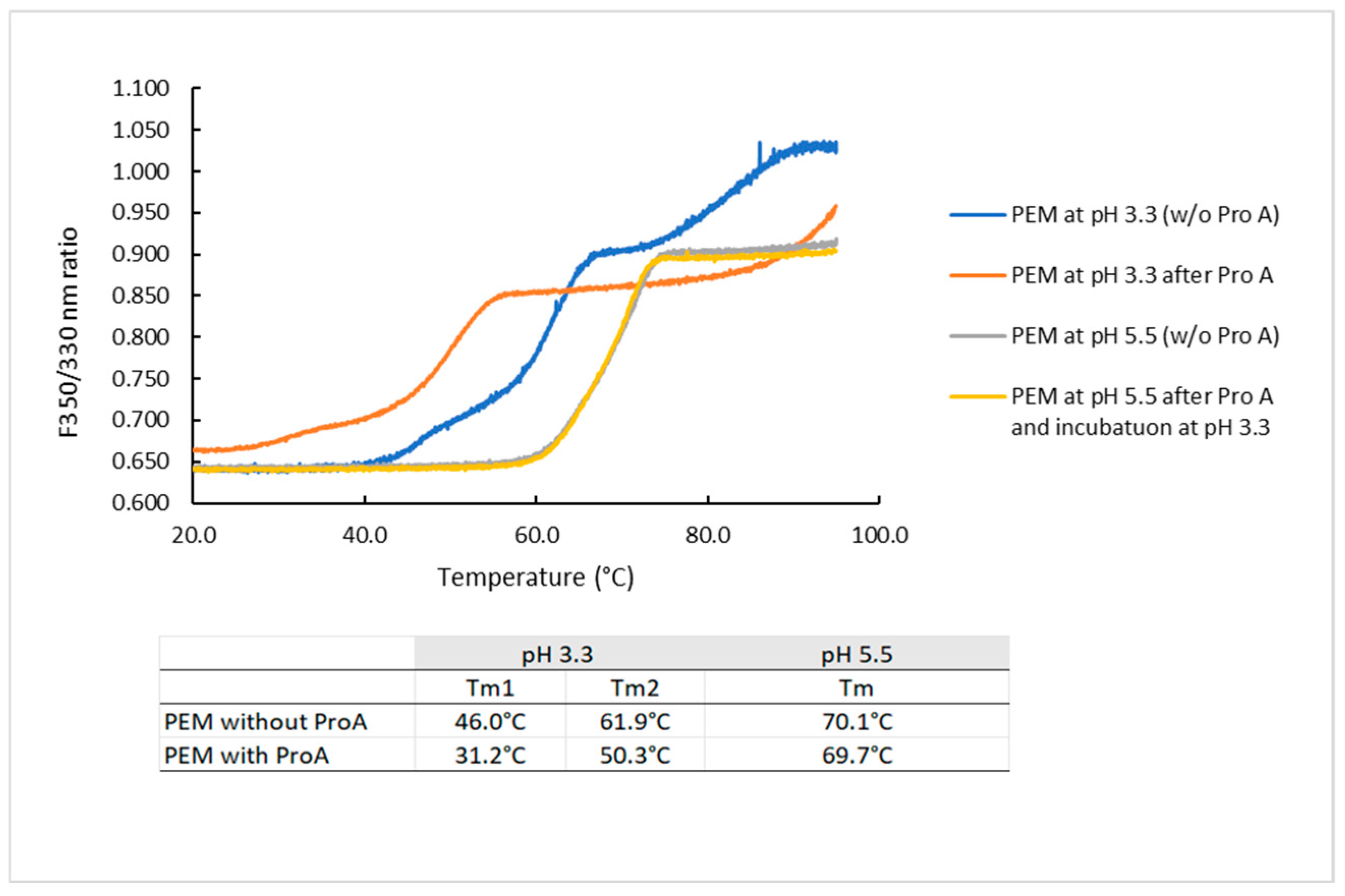

2.3. Conformational Changes in mAb Structure Following Protein a Chromatography and Low-pH Treatment

2.3.1. Effect of Protein a Chromatography and Low pH on the Melting Temperature of PEM

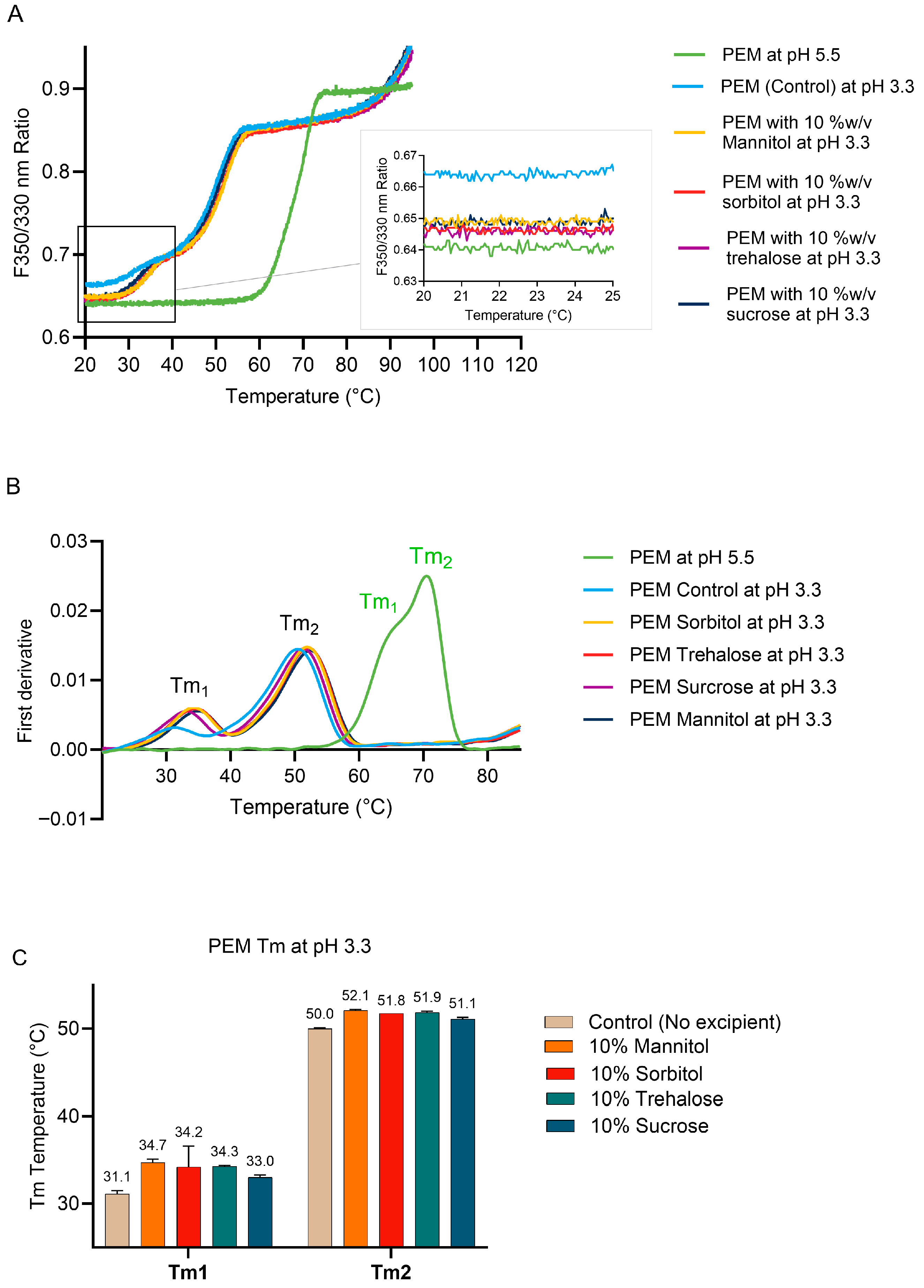

2.3.2. Effect of Excipients on PEM Conformational Stability During Low-pH Treatment

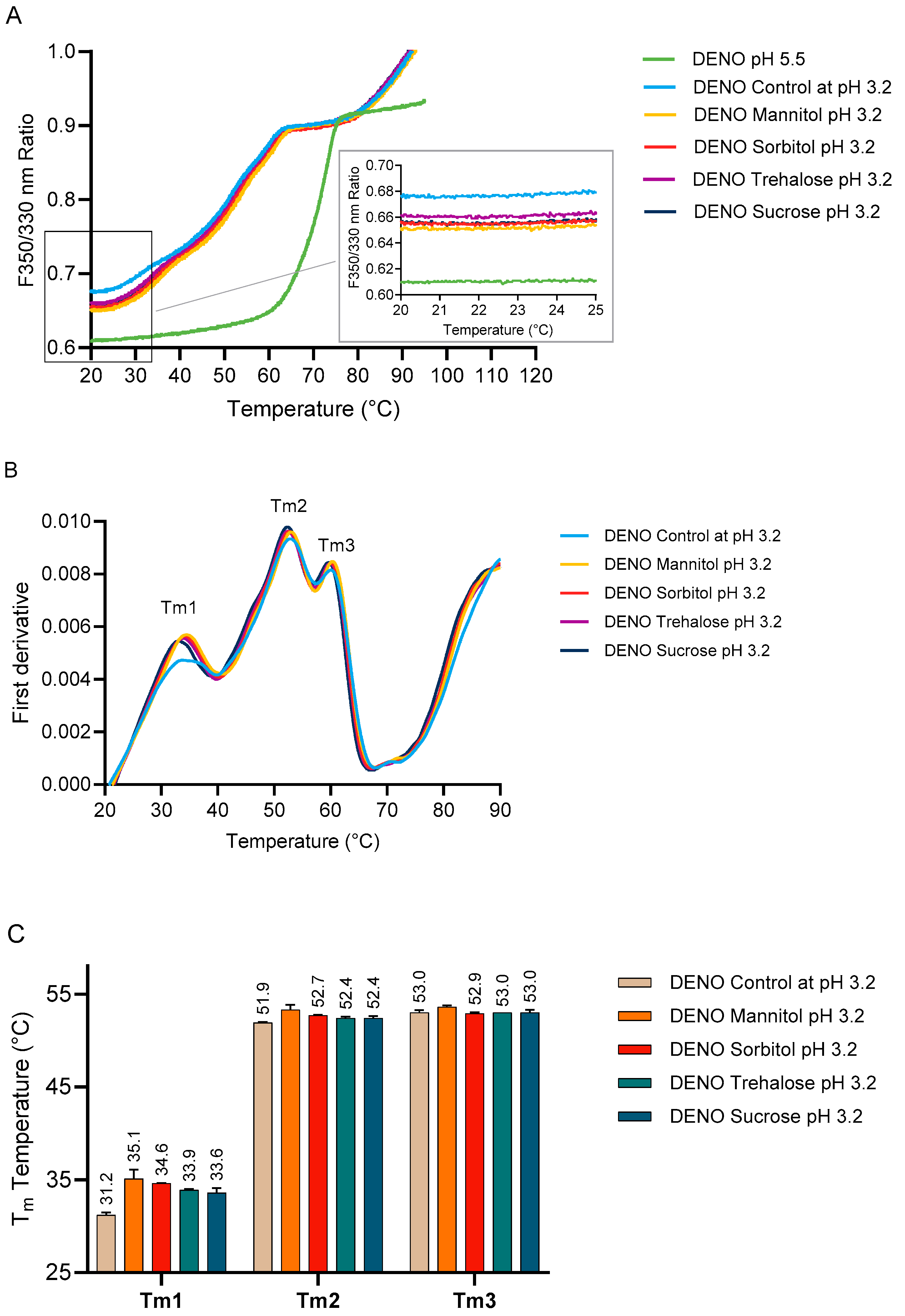

2.4. Effect of Excipients on the Stability of DENO at Low pH

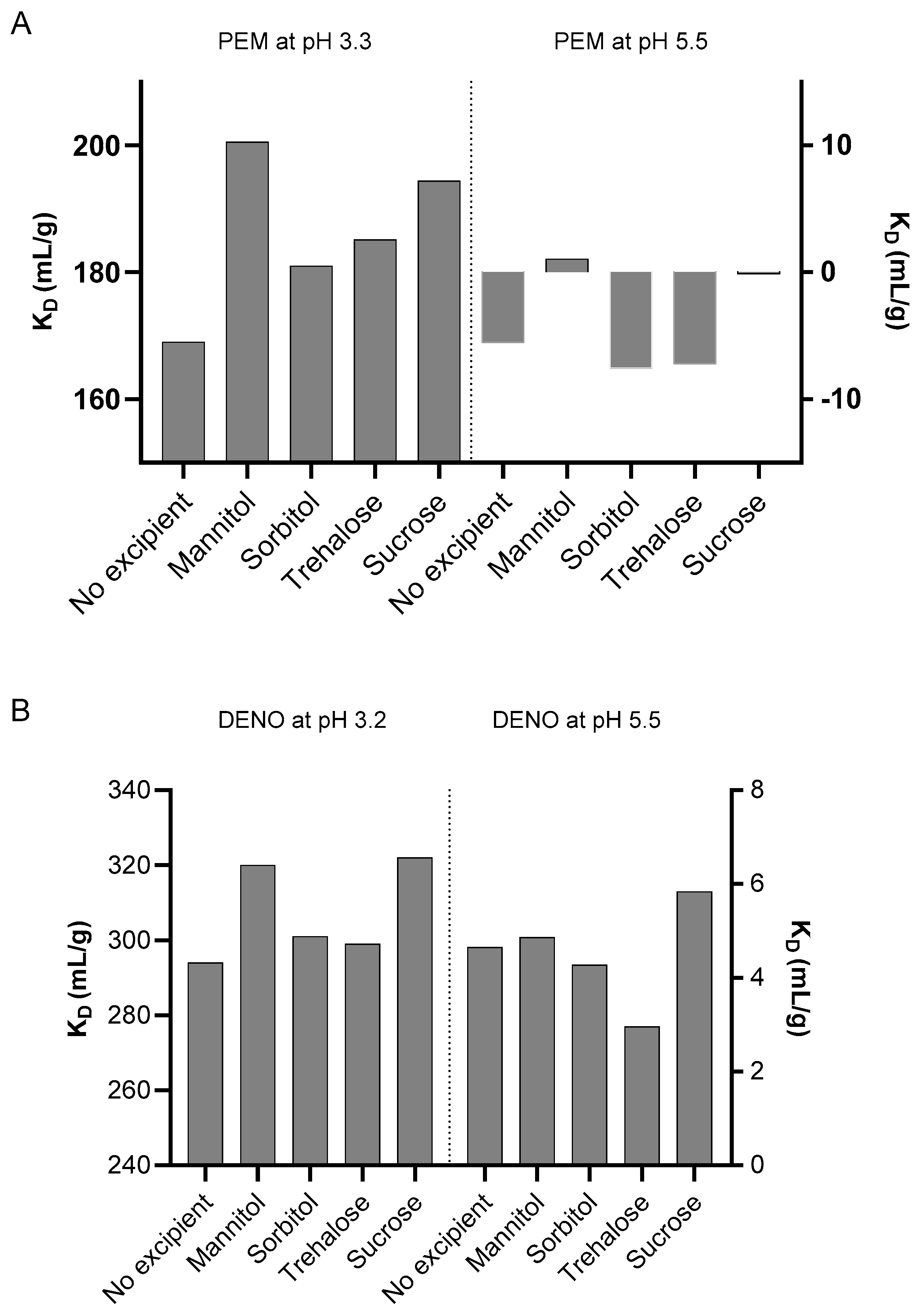

2.5. Effect of Excipients on Colloidal Stability at Low pH and Post-Neutralization Conditions

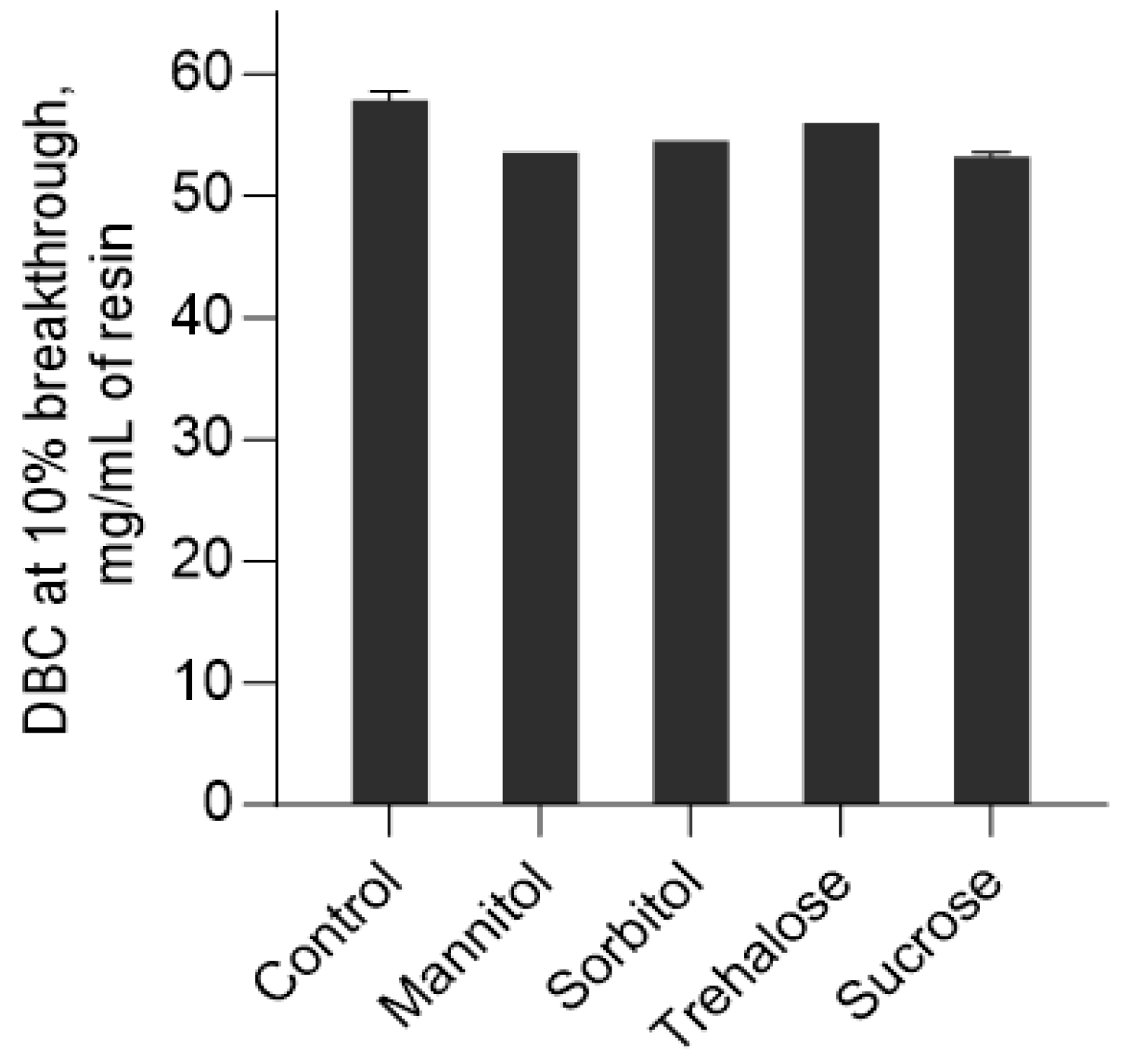

2.6. Effect of Polyols and Sugars on the Dynamic Binding Capacity of CIEX Column

3. Discussion

- Low pH causes partial or complete unfolding of mAbs. This effect is further exacerbated by prior Protein A chromatography, which increases the likelihood of structure destabilization.

- During low-pH incubation, mAbs remain in a partially unfolded state but typically do not aggregate due to strong electrostatic repulsion. The addition of polyols or sugars enhances the conformational stability of mAbs by reducing the exposure of hydrophobic residues. This enhances colloidal stability by reducing attractive forces between mAb molecules.

- Upon neutralization, with improved conformational and colloidal stability in the presence of polyols and sugars at low pH, the conformational equilibrium of the mAbs is shifted more toward the native state rather than the partially unfolded state. As a result, partially unfolded mAbs are more likely to refold correctly, rather than self-associate, thereby reducing aggregation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Antibody Batch Protein a Purification, Low-pH Incubation and Neutralization

4.2.2. Aggregate and Protein Recovery Determination by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)-HPLC

4.2.3. Cation-Exchange Chromatography (CEX) for Charge Heterogeneity Profiling of Pembrolizumab

4.2.4. Buffer Exchange of Proteins to Different pH Conditions

4.2.5. Nano Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (NanoDSF) Analysis and Tm Determination

4.2.6. Determination of KD and B22 Values from Dynamic and Static Light Scattering

4.2.7. Dynamic Binding Capacity Measurements

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lyu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Hui, J.; Wang, T.; Lin, M.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Shentu, J.; Dalby, P.A.; Zhang, H.; et al. The global landscape of approved antibody therapies. Antib. Ther. 2022, 5, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.-M.; Hwang, Y.-C.; Liu, I.-J.; Lee, C.-C.; Tsai, H.-Z.; Li, H.-J.; Wu, H.-C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenzel, A.; Hust, M.; Schirrmann, T. Expression of Recombinant Antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, P.W.; Wiebe, M.E.; Leung, J.C.; Hussein, I.T.M.; Keumurian, F.J.; Bouressa, J.; Brussel, A.; Chen, D.; Chong, M.; Dehghani, H.; et al. Viral contamination in biologic manufacture and implications for emerging therapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Anderson, J.; Utiger, E.; Ferreira, G. Viral clearance capability of monoclonal antibody purification. Biologicals 2024, 85, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzer, A.R.; Perraud, X.; Halley, J.; O’hara, J.; Bracewell, D.G. Protein A chromatography increases monoclonal antibody aggregation rate during subsequent low pH virus inactivation hold. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1415, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamris, T.; Tian, X.; Thorolfsson, M.; Karkov, H.S.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Langkilde, A.E.; Vestergaard, B. Monoclonal Antibodies Follow Distinct Aggregation Pathways During Production-Relevant Acidic Incubation and Neutralization. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH. Guidance on Viral Safety Evaluation of Biotechnology Products Derived from Cell Lines of Human or Animal Origin, Q5A. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. 1998. Available online: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q5A%28R1%29%20Guideline_0.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Shukla, A.A.; Gupta, P.; Han, X. Protein aggregation kinetics during Protein A chromatography. Case study for an Fc fusion protein. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1171, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejima, D.; Tsumoto, K.; Fukada, H.; Yumioka, R.; Nagase, K.; Arakawa, T.; Philo, J.S. Effects of acid exposure on the conformation, stability, and aggregation of monoclonal antibodies. Proteins 2007, 66, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, S.B.; Lau, H.; Razinkov, V.I.; Chen, S.; Latypov, R.F. Acid-induced aggregation of human monoclonal IgG1 and IgG2: Molecular mechanism and the effect of solution composition. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 9328–9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, H.; Honda, S. Kinetics of Antibody Aggregation at Neutral pH and Ambient Temperatures Triggered by Temporal Exposure to Acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 9581–9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latypov, R.F.; Hogan, S.; Lau, H.; Gadgil, H.; Liu, D. Elucidation of acid-induced unfolding and aggregation of human immunoglobulin IgG1 and IgG2 Fc. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Tsumoto, K. Effects of subclass change on the structural stability of chimeric, humanized, and human antibodies under thermal stress. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Vestergaard, B.; Thorolfsson, M.; Yang, Z.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Langkilde, A.E. In-depth analysis of subclass-specific conformational preferences of IgG antibodies. IUCrJ 2015, 2 Pt 1, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Ito, T.; Endo, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Sawa, E.; Wakamatsu, K. Influence of pH on heat-induced aggregation and degradation of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 1413–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Langkilde, A.E.; Thorolfsson, M.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Vestergaard, B. Small-Angle X-ray Scattering Screening Complements Conventional Biophysical Analysis: Comparative Structural and Biophysical Analysis of Monoclonal Antibodies IgG1, IgG2, and IgG4. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, H.; Xu, J.; Qin, T.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qian, W.; Li, B.; et al. Acid-induced aggregation propensity of nivolumab is dependent on the Fc. MAbs 2016, 8, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.A.; Feng, A.Z.; Ramineni, C.K.; Wallace, M.R.; Culyba, E.K.; Guay, K.P.; Mehta, K.; Mabry, R.; Farrand, S.; Xu, J.; et al. L(445)P mutation on heavy chain stabilizes IgG(4) under acidic conditions. MAbs 2019, 11, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duret, A.; Duarte, L.; Cahuzac, L.; Rondepierre, A.; Lambercier, M.; Mette, R.; Recktenwald, A.; Giovannini, R.; Bertschinger, M. Viral inactivation for pH-sensitive antibody formats such as multi-specific antibodies. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 384, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.A.; Fan, Y.; Chung, W.K.; Dutta, A.; Fiedler, E.; Haupts, U.; Peyser, J.; Kuriyel, R. Evaluation of mild pH elution protein A resins for antibodies and Fc-fusion proteins. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1713, 464523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stange, C.; Hafiz, S.; Korpus, C.; Skudas, R.; Frech, C. Influence of excipients in Protein A chromatography and virus inactivation. J. Chromatogr. B 2021, 1179, 122848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Xing, Z.; Song, Y.; Huang, C.; Xu, X.; Ghose, S.; Li, Z.J. Protein aggregation and mitigation strategy in low pH viral inactivation for monoclonal antibody purification. MAbs 2019, 11, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wälchli, R.; Ressurreição, M.; Vogg, S.; Feidl, F.; Angelo, J.; Xu, X.; Ghose, S.; Li, Z.J.; Le Saoût, X.; Souquet, J.; et al. Understanding mAb aggregation during low pH viral inactivation and subsequent neutralization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cao, C.; Wei, S.; He, H.; Chen, K.; Su, L.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Lai, Y.; Li, J. Decreasing hydrophobicity or shielding hydrophobic areas of CH2 attenuates low pH-induced IgG4 aggregation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1257665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, E.; Demarest, S.J. A broad range of Fab stabilities within a host of therapeutic IgGs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 355, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Uchida, M.; Cheung, J.; Antochshuk, V.; Shameem, M. Method qualification and application of diffusion interaction parameter and virial coefficient. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 62, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saluja, A.; Fesinmeyer, R.M.; Hogan, S.; Brems, D.N.; Gokarn, Y.R. Diffusion and sedimentation interaction parameters for measuring the second virial coefficient and their utility as predictors of protein aggregation. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoud, L.; Cohrs, N.; Arosio, P.; Norrant, E.; Morbidelli, M. Effect of Polyol Sugars on the Stabilization of Monoclonal Antibodies. Biophys. Chem. 2014, 197, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, D.D.; Hambly, D.M.; Scavezze, J.L.; Siska, C.C.; Stackhouse, N.L.; Gadgil, H.S. The effect of sucrose hydrolysis on the stability of protein therapeutics during accelerated formulation studies. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 4501–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, H.S.; Bondarenko, P.V.; Pipes, G.; Rehder, D.; McAuley, A.; Perico, N.; Dillon, T.; Ricci, M.; Treuheit, M. The LC/MS analysis of glycation of IgG molecules in sucrose containing formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 96, 2607–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, W.; Valente, J.J.; Ilott, A.; Chennamsetty, N.; Liu, Z.; Rizzo, J.M.; Yamniuk, A.P.; Qiu, D.; Shackman, H.M.; Bolgar, M.S. Investigation of anomalous charge variant profile reveals discrete pH-dependent conformations and conformation-dependent charge states within the CDR3 loop of a therapeutic mAb. MAbs 2020, 12, 1763138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Bourret, J.; Cano, T. Isolation and characterization of therapeutic antibody charge variants using cation exchange displacement chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 5079–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A.; Paisley-Flango, K.; Tangarone, B.S.; Porter, T.J.; Rouse, J.C. Cation exchange–HPLC and mass spectrometry reveal C-terminal amidation of an IgG1 heavy chain. Anal. Biochem. 2007, 360, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasak, J.; Ionescu, R. Heterogeneity of Monoclonal Antibodies Revealed by Charge-Sensitive Methods. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2008, 9, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, P.; Nian, R. Conformational plasticity of IgG during protein A affinity chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1433, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lord, H.; Knutson, N.; Wikström, M. Nano differential scanning fluorimetry for comparability studies of therapeutic proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 593, 113581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, E.J.; Na, D.H. Nano Differential Scanning Fluorimetry-Based Thermal Stability Screening and Optimal Buffer Selection for Immunoglobulin G. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooran, N.; Kopra, K. Fluorescence-Based Protein Stability Monitoring-A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PEM | DENO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate (%) | Protein Recovery (%) | Aggregate (%) | Protein Recovery (%) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| T0 | 0.36 (0.01) | 100.0 | 1.77 | 100.0 |

| pH 3.5 | 2.05 (0.00) | 99.6 (0.00) | 2.63 | 99.5 |

| pH 3.4 | 12.10 (0.02) | 93.7 (0.1) | 3.59 | 98.4 |

| pH 3.3 | 36.05 (0.05) | 85.2 (0.2) | 5.82 | 98.7 |

| pH 3.2 | 40.94 (0.21) | 77.0 (0.9) | 11.51 | 96.0 |

| pH 3.1 | 35.68 (0.37) | 69.2 (2.5) | 30.54 | 88.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.; Peng, T.; Goh, L.Y.H.; Chow, K.T.; Bahl, D.; Tuliani, V. Understanding the Role of Polyols and Sugars in Reducing Aggregation in IgG2 and IgG4 Monoclonal Antibodies During Low-pH Viral Inactivation Step. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121846

Hong S, Peng T, Goh LYH, Chow KT, Bahl D, Tuliani V. Understanding the Role of Polyols and Sugars in Reducing Aggregation in IgG2 and IgG4 Monoclonal Antibodies During Low-pH Viral Inactivation Step. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121846

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Shiqi, Tao Peng, Lucas Yuan Hao Goh, Keat Theng Chow, Deepak Bahl, and Vinod Tuliani. 2025. "Understanding the Role of Polyols and Sugars in Reducing Aggregation in IgG2 and IgG4 Monoclonal Antibodies During Low-pH Viral Inactivation Step" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121846

APA StyleHong, S., Peng, T., Goh, L. Y. H., Chow, K. T., Bahl, D., & Tuliani, V. (2025). Understanding the Role of Polyols and Sugars in Reducing Aggregation in IgG2 and IgG4 Monoclonal Antibodies During Low-pH Viral Inactivation Step. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121846