Advances in Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

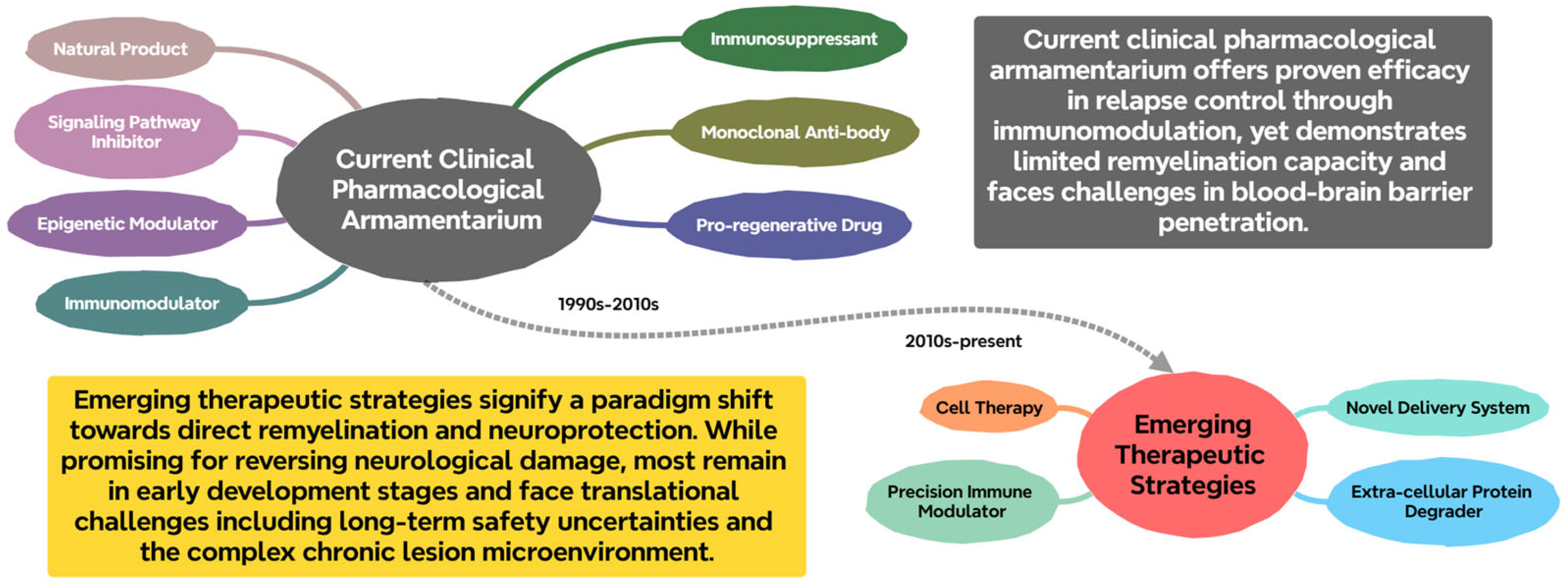

2. Current Landscape of Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases

2.1. Immunomodulatory and Immunosuppressive Agents

2.1.1. Immunomodulators

2.1.2. Immunosuppressants

2.2. Monoclonal Antibody-Based Therapeutics

2.3. Promyelinating and Neuroprotective Agents

2.3.1. Pro-Regenerative Drugs Targeting Oligodendrocyte Maturation

GPR17 Antagonists

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Antagonists

GABA-A Receptor Modulators

2.3.2. Epigenetic Modulators

HDAC Inhibitors (HDACi)

DNA Demethylating Agents

Histone Methylation Modulators

2.3.3. Signaling Pathway Inhibitors and Targeted Therapies

BTK Inhibitors

CCR5 Inhibitors

Nogo-A Antagonists

2.4. Natural Products from Traditional Chinese Medicine

2.4.1. Gastrodin

2.4.2. Astragaloside IV

2.4.3. Triptolide

2.4.4. Tanshinone IIA

2.4.5. Resveratrol

2.5. Novel Therapeutic Strategies and Technologies

2.5.1. Novel Delivery Systems

Exosome-Based Combination Therapy

Nanodrug Delivery Systems

2.5.2. Targeted Antibody Clearance Strategy

Extracellular Protein Degradation Technology

Precision Immune Modulators

2.5.3. Cell Therapies

BCMA CAR-T Cell Therapy

Microglial Replacement Therapy

Engineered Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy

2.5.4. Gene Therapy

2.5.5. Re-Myelination Method Based on CRISPR/Cas9

3. Challenges and Strategies in Drug Development

3.1. Challenges

3.1.1. Disease Heterogeneity and the Lack of Precision Medicine

3.1.2. The Blood–Brain Barrier Limitation and Central Delivery Hurdles

3.1.3. Long-Term Drug Safety and Tolerability Issues

3.1.4. The Translational Gap Between Preclinical Models and Human Disease

3.2. Strategies

3.2.1. Precision Medicine and Biomarker Development

3.2.2. Development and Application of Novel Delivery Systems

3.2.3. Multi-Target Synergistic Therapeutic Strategies

3.2.4. Non-Immune Directed Repair Therapies

3.2.5. Innovation in Clinical Research Paradigms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Compston, A.; Coles, A. Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet 2008, 372, 1502–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, G.; Michaud, M.; Pittion-Vouyovitch, S.; Debouverie, M. Classification and Diagnostic Criteria for Demyelinating Diseases of the Central Nervous System: Where Do We Stand Today? Rev. Neurol. 2018, 174, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftimov, F.; Lucke, I.M.; Querol, L.A.; Rajabally, Y.A.; Verhamme, C. Diagnostic Challenges in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy. Brain J. Neurol. 2020, 143, 3214–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höftberger, R.; Lassmann, H. Inflammatory Demyelinating Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 145, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal Analysis Reveals High Prevalence of Epstein-Barr Virus Associated with Multiple Sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Multiple Sclerosis Genomic Map Implicates Peripheral Immune Cells and Microglia in Susceptibility. Science 2019, 365, eaav7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchroo, V.K.; Weiner, H.L. How Does Epstein-Barr Virus Trigger MS? Immunity 2022, 55, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, T.; Zheng, Z.; Su, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, C.; Yu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; et al. Oligodendroglial Precursor Cells Modulate Immune Response and Early Demyelination in a Murine Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadn9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Shao, Q.; Wu, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Chang, X.; Zhu, K.; et al. GSDME-Mediated Pyroptosis in Microglia Exacerbates Demyelination and Neuroinflammation in Multiple Sclerosis: Insights from Humans and Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination Model Mice. Cell Death Differ. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren-Rose, Å.; Natarajan, C.; Matta, P.; Pandey, A.; Upender, I.; Sriram, S. Anacardic Acid Induces IL-33 and Promotes Remyelination in CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 21527–21535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brola, W.; Steinborn, B. Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis—Current Status of Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2020, 54, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez, M.; Rivas, V.; Sanín, L.H.; Trujillo, M.; Castillo, R.; Flores, J.; Blaisdell, C. Epidemiology of Demyelinating Diseases in Mexico: A Registry-Based Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 75, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, H.; Fujihara, K. Demyelinating Diseases in Asia. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2016, 29, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, M.; Makosa, B.; Walczak, A.; Selmaj, K. Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Resisted to Glucocorticoid Therapy: Abnormal Expression of Heat-Shock Protein 90 in Glucocorticoid Receptor Complex. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Vidal-Jordana, A.; Montalban, X. Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Aspects. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.P. Glatiramer Acetate and the Glatiramoid Class of Immunomodulator Drugs in Multiple Sclerosis: An Update. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus Farber, R.; Harel, A.; Lublin, F. Novel Agents for Relapsing Forms of Multiple Sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 2016, 67, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comi, G.; Martinelli, V.; Rodegher, M.; Moiola, L.; Bajenaru, O.; Carra, A.; Elovaara, I.; Fazekas, F.; Hartung, H.P.; Hillert, J.; et al. Effect of Glatiramer Acetate on Conversion to Clinically Definite Multiple Sclerosis in Patients with Clinically Isolated Syndrome (PreCISe Study): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 1503–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.; Filippi, M.; Arnason, B.; Comi, G.; Cook, S.; Goodin, D.; Hartung, H.-P.; Jeffery, D.; Kappos, L.; Boateng, F.; et al. 250 Microg or 500 Microg Interferon Beta-1b versus 20 Mg Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Prospective, Randomised, Multicentre Study. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikol, D.D.; Barkhof, F.; Chang, P.; Coyle, P.K.; Jeffery, D.R.; Schwid, S.R.; Stubinski, B.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J.; REGARD study group. Comparison of Subcutaneous Interferon Beta-1a with Glatiramer Acetate in Patients with Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis (the REbif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing MS Disease [REGARD] Study): A Multicentre, Randomised, Parallel, Open-Label Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadavid, D.; Wolansky, L.J.; Skurnick, J.; Lincoln, J.; Cheriyan, J.; Szczepanowski, K.; Kamin, S.S.; Pachner, A.R.; Halper, J.; Cook, S.D. Efficacy of Treatment of MS with IFNbeta-1b or Glatiramer Acetate by Monthly Brain MRI in the BECOME Study. Neurology 2009, 72, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.D.; Rossman, H.; Bar-Or, A.; Miller, A.; Miller, D.H.; Schmierer, K.; Lublin, F.; Khan, O.; Bormann, N.M.; Yang, M.; et al. GLANCE: Results of a Phase 2, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Neurology 2009, 72, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, T.; Panitch, H.; Bar-Or, A.; Dunn, J.; Freedman, M.S.; Gazda, S.K.; Campagnolo, D.; Deutsch, F.; Arnold, D.L. Glatiramer Acetate after Induction Therapy with Mitoxantrone in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggeri, A.; Schepers, M.; Tiane, A.; Rombaut, B.; van Veggel, L.; Hellings, N.; Prickaerts, J.; Pittaluga, A.; Vanmierlo, T. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Modulators and Oligodendroglial Cells: Beyond Immunomodulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, P.K.; Freedman, M.S.; Cohen, B.A.; Cree, B.A.C.; Markowitz, C.E. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Modulators in Multiple Sclerosis Treatment: A Practical Review. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2024, 11, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Quan, C. Effectiveness and Tolerability of Immunosuppressants and Monoclonal Antibodies in Preventive Treatment of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 35, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, S.A. In MS: Immunosuppression Is Passé. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 40, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittock, S.J.; Zekeridou, A.; Weinshenker, B.G. Hope for Patients with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders—From Mechanisms to Trials. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briani, C.; Visentin, A. Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody Therapies in Chronic Autoimmune Demyelinating Neuropathies. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xue, B.; Li, X.; Xia, J. Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Current and Future. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, P.; Roszkowska, Z.; Adamus, S.; Kasarełło, K. Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Overview of Current Pharmacotherapies and Emerging Treatment Prospects. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, S.R.; Faissner, S.; Linker, R.A.; Rammohan, K. Key Characteristics of Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies and Clinical Implications for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 1515–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewash, M.; Kostenis, E.; Müller, C.E. GPR17—Orphan G Protein-Coupled Receptor with Therapeutic Potential. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucci, G.; Dal Ben, D.; Lambertucci, C.; Santinelli, C.; Spinaci, A.; Thomas, A.; Volpini, R.; Buccioni, M. The G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR17: Overview and Update. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 2567–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, S.; Clausen, B.H.; Mannella, F.C.; Wirenfeldt, M.; Marangon, D.; Tidgen, S.B.; Corradini, S.; Madsen, K.; Lecca, D.; Abbracchio, M.P.; et al. Characterisation of GPR17-Expressing Oligodendrocyte Precursors in Human Ischaemic Lesions and Correlation with Reactive Glial Responses. J. Pathol. 2025, 265, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Koito, H.; Li, J.; Ye, F.; Hoang, J.; Escobar, S.S.; Gow, A.; Arnett, H.A.; et al. The Oligodendrocyte-Specific G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR17 Is a Cell-Intrinsic Timer of Myelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamoya, S.; Leopold, P.; Becker, B.; Beyer, C.; Hustadt, F.; Schmitz, C.; Michel, A.; Kipp, M. G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr17 Expression in Two Multiple Sclerosis Remyelination Models. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Dong, L.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Huang, G.; Bai, S.J.; Liao, L. G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr17 Regulates Oligodendrocyte Differentiation in Response to Lysolecithin-Induced Demyelination. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp, M. Remyelination Strategies in Multiple Sclerosis: A Critical Reflection. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2016, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plemel, J.R.; Liu, W.-Q.; Yong, V.W. Remyelination Therapies: A New Direction and Challenge in Multiple Sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Park, E.; Abd-Elrahman, K.S. Enhancing Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis via M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2025, 107, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ren, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Wu, S.; Gao, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, F.; Yu, B.; et al. Ospemifene, a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator, Enhances Oligodendrocyte Myelination and Preserves Neurofunctions Against Injuries. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caverzasi, E.; Papinutto, N.; Cordano, C.; Kirkish, G.; Gundel, T.J.; Zhu, A.; Akula, A.V.; Boscardin, W.J.; Neeb, H.; Henry, R.G.; et al. MWF of the Corpus Callosum Is a Robust Measure of Remyelination: Results from the ReBUILD Trial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217635120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Uriza, F.; Ordaz, R.P.; Garay, E.; Cisneros-Mejorado, A.J.; Arellano, R.O. N-Butyl-β-Carboline-3-Carboxylate (β-CCB) Systemic Administration Promotes Remyelination in the Cuprizone Demyelinating Model in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Ji, B.; Chen, H.; Liu, D.; Li, L.; Du, G. The Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Belinostat Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Mice by Inhibiting TLR2/MyD88 and HDAC3/NF-κB P65-Mediated Neuroinflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 176, 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, N.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Loers, G.; Siebert, H.-C.; Wen, M.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.; et al. HDAC3 Inhibitor RGFP966 Ameliorated Neuroinflammation in the Cuprizone-Induced Demyelinating Mouse Model and LPS-Stimulated BV2 Cells by Downregulating the P2X7R/STAT3/NF-κB65/NLRP3 Activation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2579–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.W.Y.; Chang, C.-B.; Tung, C.-H.; Sun, J.; Suen, J.-L.; Wu, S.-F. Low-Dose 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine Pretreatment Inhibits Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Induction of Regulatory T Cells. Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, K.; Fagone, P.; Bendtzen, K.; Meroni, P.L.; Quattrocchi, C.; Mammana, S.; Di Rosa, M.; Malaguarnera, L.; Coco, M.; Magro, G.; et al. Hypomethylating Agent 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine (DAC) Ameliorates Multiple Sclerosis in Mouse Models. J. Cell Physiol. 2014, 229, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S.; Villar, L.M.; Costa, C.; Midaglia, L.; Cubedo, M.; Medina, S.; Fissolo, N.; Río, J.; Castilló, J.; Álvarez-Cermeño, J.C.; et al. Circulating EZH2-Positive T Cells Are Decreased in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Zong, L.; Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Luo, C.; Yang, X.; Fang, H.; Kong, X.; et al. Development of a First-in-Class DNMT1/HDAC Inhibitor with Improved Therapeutic Potential and Potentiated Antitumor Immunity. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 16480–16504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.J.; Bar-Or, A.; Traboulsee, A.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Giovannoni, G.; Vermersch, P.; Syed, S.; Li, Y.; Vargas, W.S.; Turner, T.J.; et al. Tolebrutinib in Nonrelapsing Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Li, H.; Chang, T.; He, W.; Kong, Y.; Qi, C.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, P.; et al. Bone Marrow Hematopoiesis Drives Multiple Sclerosis Progression. Cell 2022, 185, 2234–2247.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatakis, I.; Papagianni, F.; Theodorakis, K.; Karagogeos, D. Nogo-A and LINGO-1: Two Important Targets for Remyelination and Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; He, Y.; Ge, M.; Liu, P.; Zheng, P.; Li, Z. Gastrodin Promotes CNS Myelinogenesis and Alleviates Demyelinating Injury by Activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 1610–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, R.J.M. Why Does Remyelination Fail in Multiple Sclerosis? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedoni, S.; Scherma, M.; Camoglio, C.; Siddi, C.; Dazzi, L.; Puliga, R.; Frau, J.; Cocco, E.; Fadda, P. An Overall View of the Most Common Experimental Models for Multiple Sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 184, 106230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Mu, B.; Guo, M.; Liu, C.; Meng, T.; Yan, Y.; Song, L.; Yu, J.; Kumar, G.; Ma, C. Astragaloside IV Inhibits Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Modulating the Polarization of Both Microglia/Macrophages and Astrocytes. Folia Neuropathol. 2023, 61, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xing, F.; Han, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, H.; Shi, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, F.; Wu, X. Astragaloside IV Regulates Differentiation and Induces Apoptosis of Activated CD4+ T Cells in the Pathogenesis of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 362, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, F. Tripterygium Glycoside Tablets and Triptolide Alleviate Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Mice Involving the PACAP/cAMP Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 347, 119748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yang, X.; Han, D.; Feng, J. Tanshinone IIA Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, J. Treatment with Tanshinone IIA Suppresses Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier and Reduces Expression of Adhesion Molecules and Chemokines in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 771, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sun, K.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhu, H.; Yu, F.; Zhao, W. Resveratrol-Loaded Macrophage Exosomes Alleviate Multiple Sclerosis through Targeting Microglia. J. Control. Release 2023, 353, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsher, E.; Khan, R.S.; Davis, B.M.; Dine, K.; Luong, V.; Somavarapu, S.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Shindler, K.S. Nanoparticles Enhance Solubility and Neuroprotective Effects of Resveratrol in Demyelinating Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1138–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-J.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Wei, B.; Tao, X.; Yu, C.-C.; Shi, L.-N.; Wang, Z.-H.; Li, X.; Wang, L.-B. Olig2-Enriched Exosomes: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination. Neuroscience 2024, 555, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasaniani, N.; Nouri, S.; Shirzad, M.; Rostami-Mansoor, S. Potential Therapeutic and Diagnostic Approaches of Exosomes in Multiple Sclerosis Pathophysiology. Life Sci. 2024, 347, 122668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komlakh, K.; Aghamiri, S.H.; Farshadmoghadam, H. The Role and Therapeutic Applications of Exosomes in Multiple Sclerosis Disease. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhabi, B.M.; Asfour, H.Z.; Okbazghi, S.Z.; Al-Rabia, M.W.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Sirwi, A.; Badr-Eldin, S.M.; Abdel-Naim, A.B.; Ashour, O.M. Glatiramer–Diclofenac Nanocomplex Enhances Remyelination in a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, R.R.; Lu, D.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Monroy, E.Y.; Wang, J. Targeted Protein Degradation via Lysosomes. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, T.; Muley, S. Early Deterioration of CIDP Following Transition from IVIG to FcRn Inhibitor Treatment. J. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 468, 123313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.-H.; Mei, Z.-C.; Zhou, L.-Q.; Heming, M.; Xu, L.-L.; Liu, Y.-X.; Pang, X.-W.; Chu, Y.-H.; Cai, S.-B.; Ye, H.; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR-T Cell Therapy in Relapsed/Refractory Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. Med 2025, 6, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Lu, R.; Lü, L.; Yao, Q.; Yang, K.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X.; Pan, R.; Ma, Y. Olig2+ Single-Colony-Derived Cranial Bone-Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Achieve Improved Regeneration in a Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination Mouse Model. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2024, 25, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargiannidou, I.; Kagiava, A.; Kleopa, K.A. Gene Therapy Approaches Targeting Schwann Cells for Demyelinating Neuropathies. Brain Res. 2020, 1728, 146572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, G.N.; Namaganda, S.J.; Kumar, M.M.; Hamilton, J.R.; Sharma, R.; Chow, K.G.; Workley, L.A.; Macklin, B.L.; Sun, M.; Ha, A.S.; et al. Characterizing and Controlling CRISPR Repair Outcomes in Nondividing Human Cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadarevian, J.P.; Davtyan, H.; Chadarevian, A.L.; Nguyen, J.; Capocchi, J.K.; Le, L.; Escobar, A.; Chadarevian, T.; Mansour, K.; Deynega, E.; et al. Harnessing Human iPSC-Microglia for CNS-Wide Delivery of Disease-Modifying Proteins. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 914–934.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug/Therapy Name | Category | Primary Target/Mechanism | Indication (or Research Model) | Stage of Development | Key Features/Challenges | Cited References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon-beta (IFN-β) | Immunomodulator | Inhibits T-cell migration across BBB; downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines | RRMS, CIS | Approved | First-line injectable; reduces relapse rate; ineffective for PPMS | [15,17] |

| Glatiramer Acetate (GA) | Immunomodulator | Mimics MBP to induce immune tolerance; promotes Th2/Treg cells | RRMS, CIS | Approved | First-line injectable; delays conversion from CIS to CDMS | [15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23] |

| Fingolimod, Ozanimod, Ponesimod, Siponimod | S1P Receptor Modulator | Modulates S1P receptors; sequesters lymphocytes in lymph nodes | Relapsing MS forms (CIS, RRMS, active SPMS) | Approved | Oral administration; sustained efficacy; first-dose cardiac effects, infection risk | [24,25] |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) | Immunosuppressant | Inhibits purine synthesis; blocks T/B cell proliferation | NMOSD (Off-label) | Clinical Use/Off-label | Good tolerability; superior EDSS Improvement Vs. CTX; mostly mild AEs | [26,27] |

| Tacrolimus | Immunosuppressant | Inhibits calcineurin pathway; suppresses T-cell activation | NMOSD (Off-label) | Clinical Use/Off-label | Promotes early neurological recovery; significant corticosteroid-sparing effect | [26,27] |

| Eculizumab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-C5 complement; inhibits CDC and MAC formation | AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD | Approved | High efficacy (96-week relapse-free rate of 96%); requires meningococcal infection prophylaxis | [28,29,30] |

| Satralizumab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-IL-6 receptor; inhibits plasmablast differentiation and antibody production | AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD | Approved | Subcutaneous administration; no benefit in seronegative subgroup | [28,29,30] |

| Inebilizumab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-CD19; depletes B-cell lineages (including plasmablasts) | NMOSD | Approved | Broader B-cell depletion; reduces relapse risk by 73% at 28 weeks | [28,29,30] |

| Rituximab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-CD20; depletes B cells | RRMS (Off-label) | Off-label/Clinical Use | Rapidly suppresses new lesion formation in RRMS | [31,32] |

| Ocrelizumab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-CD20; depletes B cells; downregulates CD8+ T cell and NK cell cytotoxicity | RRMS, PPMS | Approved | Stabilizes disability progression; reduces serum NfL levels; long-term B-cell depletion may increase infection risk | [31,32] |

| Natalizumab | Monoclonal Antibody | Anti-α4β1-integrin; blocks immune cell migration across BBB | RRMS | Approved | Highly effective in reducing relapses and lesions; requires rigorous PML monitoring | [31,32] |

| GPR17 Antagonists (e.g., Pranlukast, PTD802) | Pro-regenerative Drug | Antagonizes GPR17 (Gi-coupled), relieving inhibition of OPC differentiation and promoting remyelination | MS (EAE, Cuprizone, LPC models) | Preclinical | Promotes remyelination in models; animal models primarily assess “acceleration” of repair, not “de novo” regeneration; clinical assessment challenging | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] |

| Ospemifene | Pro-regenerative Drug | Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM); promotes OPC differentiation and maturation | MS, Neonatal WMI (In vitro, EAE model) | Preclinical/Translational | FDA-approved for other indications; crosses BBB; efficacy in multiple injury models; precise molecular target unclear | [42] |

| Clemastine | Pro-regenerative Drug | M1 muscarinic receptor antagonist; promotes OPC differentiation and remyelination | MS (ReBUILD Trial) | Phase II Completed | Significantly increased corpus callosum MWF and shortened VEP latency; efficacy may be region-specific | [43] |

| β-CCB | Pro-regenerative Drug | Positive allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors (containing α3γ1 subunit) on OLs; promotes OPC differentiation | MS (Cuprizone model) | Preclinical | High target specificity; effective upon systemic administration without inducing convulsions; suboptimal repair efficacy in gray matter | [44] |

| RGFP966 | Epigenetic Modulator | Selective HDAC3 inhibitor; suppresses microglial P2X7R/NLRP3/NF-κB/STAT3 signaling | Demyelination (Cuprizone model, BV2 cells) | Preclinical | Ameliorates demyelination and motor deficits; selective targeting may reduce toxicity vs. pan-HDACi; lacks human trial data | [45,46] |

| Decitabine (DAC) | Epigenetic Modulator | DNA demethylating agent; upregulates Foxp3, increases Tregs, inhibits Th17 | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Preventive and therapeutic effects in EAE; disease relapse after discontinuation; long-term use raises concerns about genomic instability and tumor risk | [47,48] |

| RG108 | Epigenetic Modulator | Non-nucleoside DNMT inhibitor; induces genomic DNA demethylation, promotes OPC differentiation | MS (Cell models) | Preclinical | Promotes OPC differentiation; broad suppression of genomic methylation may disrupt epigenetic homeostasis; only cell model data | - |

| Tolebrutinib | Signaling Pathway Inhibitor | BTK inhibitor (BBB-penetrant); inhibits peripheral B cells & myeloid cells; modulates CNS microenvironment | Non-relapsing SPMS (Phase III HERCULES) | Phase III | Reduces risk of disability progression and new MRI lesions; dual immunomodulatory and central actions; hepatotoxicity risk requires monitoring | [51] |

| Thioraviroc | Signaling Pathway Inhibitor | CCR5 inhibitor; blocks migration of bone marrow-derived myeloid cells into CNS | MS (EAE models: acute, relapsing, progressive) | Phase I Completed | Oral small molecule; superior to teriflunomide in preclinical models; efficacy and long-term safety in MS patients require larger trials | [52] |

| Nogo-A Antagonists | Signaling Pathway Inhibitor | Blocks Nogo-A interaction with NgR1/S1PR2; inhibits RhoA/ROCK pathway | MS, ALS (EAE, LPC models) | Phase II (Primary endpoints not met) | Preclinical improvement in demyelination and functional recovery; limited BBB penetration of antibodies; inconsistent clinical efficacy | [53] |

| Gastrodin | Natural Product | Activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling; enhances myelinating capacity of mature OLs | MS (Zebrafish, LPC, EAE models) | Preclinical | Reduces lesion volume, increases myelin thickness, promotes mature OLs; all data from animal models | [54,55,56] |

| Astragaloside IV | Natural Product | Inhibits TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway; modulates microglia/macrophage (M1/M2) and astrocyte (A1/A2) polarization | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Multi-target synergy (anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective); low toxicity; lacks human trial data | [57,58] |

| Triptolide (TP) | Natural Product | Modulates PACAP/cAMP axis; inhibits NF-κB; activates PI3K/AKT; inhibits oligodendrocyte apoptosis | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Core component of Tripterygium glycosides; improves EAE scores; extremely narrow therapeutic window; reproductive toxicity concerns | [59] |

| Tanshinone IIA (TSIIA) | Natural Product | Multi-target: reduces T cell infiltration, blocks IL-23/IL-17 axis, potential antioxidant | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Multi-target immunomodulation; lipophilicity and low oral bioavailability; lacks human data | [60,61] |

| Resveratrol (RSV) | Natural Product | Inhibits NF-κB; reduces ROS via SIRT1; (RSV-Exo) delivered via macrophage exosomes for microglia targeting | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Exosome delivery enables CNS targeting and avoids systemic exposure; low aqueous solubility and rapid metabolism of free RSV; complex manufacturing of exosomes | [62,63] |

| Drug/Therapy Name | Category | Primary Target/Mechanism | Indication (or Research Model) | Stage of Development | Key Features/Challenges | Cited References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exosome-Based Therapy | Novel Delivery System | Natural carriers for targeted drug delivery (e.g., miR-219, anti-inflammatory agents) to CNS | MS | Preclinical | High biocompatibility, ability to cross BBB; challenges include heterogeneity in sources/cargo and standardization of isolation | [64,65,66] |

| GA-DCL Nanocomplex | Novel Delivery System | Nano-co-encapsulation of GA and Dexamethasone for synergistic immunomodulation & targeted delivery | MS (EAE model) | Preclinical | Enhances BBB penetration and lesion targeting; improves efficacy and safety vs. free drugs; not yet in clinical trials | [67] |

| MoDE Platform (e.g., KJ103, BHV-1300) | Extracellular Protein Degrader | Bifunctional molecule binds pathogenic IgG and hepatocyte ASGPR, directing it to lysosomal degradation | AIDP, CIDP (KJ103: Phase III; BHV-1300: Phase I) | Phase I/Phase III | Rapidly clears pathogenic antibodies; KJ103 received Breakthrough Therapy Designation in China; CNS delivery remains a challenge | [68] |

| FcRn Inhibitors (e.g., Efgartigimod) | Precision Immune Modulator | Blocks FcRn in endothelial cells, inhibiting IgG recycling and accelerating autoantibody degradation | CIDP (Approved in EU), NMOSD | Phase III/Approved (varies) | Subcutaneous administration; precise mechanism; ineffective in T-cell dominated diseases (e.g., MS); risk of deterioration during transition from IVIg | [69] |

| BCMA CAR-T | Cell Therapy | Targets and clears BCMA+ plasmablasts/plasma cells; blocks autoantibody production | Refractory CIDP (Case Reports) | Early Clinical Research | Achieved drug-free remission (sustained in one patient > 24 months); single infusion; relapse risk exists | [70] |

| AAV-mediated Gene Replacement | Gene Therapy | Delivers normal genes (e.g., GJB1/Cx32 for CMT1X, SH3TC2 for CMT4C) to Schwann cells via viral vectors | Demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) | Preclinical | Partial phenotypic rescue in animal models; challenges include limited transduction efficiency in Schwann cells and durability of gene expression | [72] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, X.; Fu, H. Advances in Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121835

Jiang J, Sun Y, Ma Y, Xu C, Zhao X, Fu H. Advances in Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121835

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Jinhui, Yuchen Sun, Yuan Ma, Chenhui Xu, Xiaofeng Zhao, and Hui Fu. 2025. "Advances in Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121835

APA StyleJiang, J., Sun, Y., Ma, Y., Xu, C., Zhao, X., & Fu, H. (2025). Advances in Therapeutics Research for Demyelinating Diseases. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121835