Unveiling the Cytotoxicity Potential of Nanoemulsion of Peltophorum pterocarpum Extract: A Natural Hemocompatible Injection Competing with Doxorubicin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Standardization of Bergenin in P. pterocarpum Extract Using HPLC

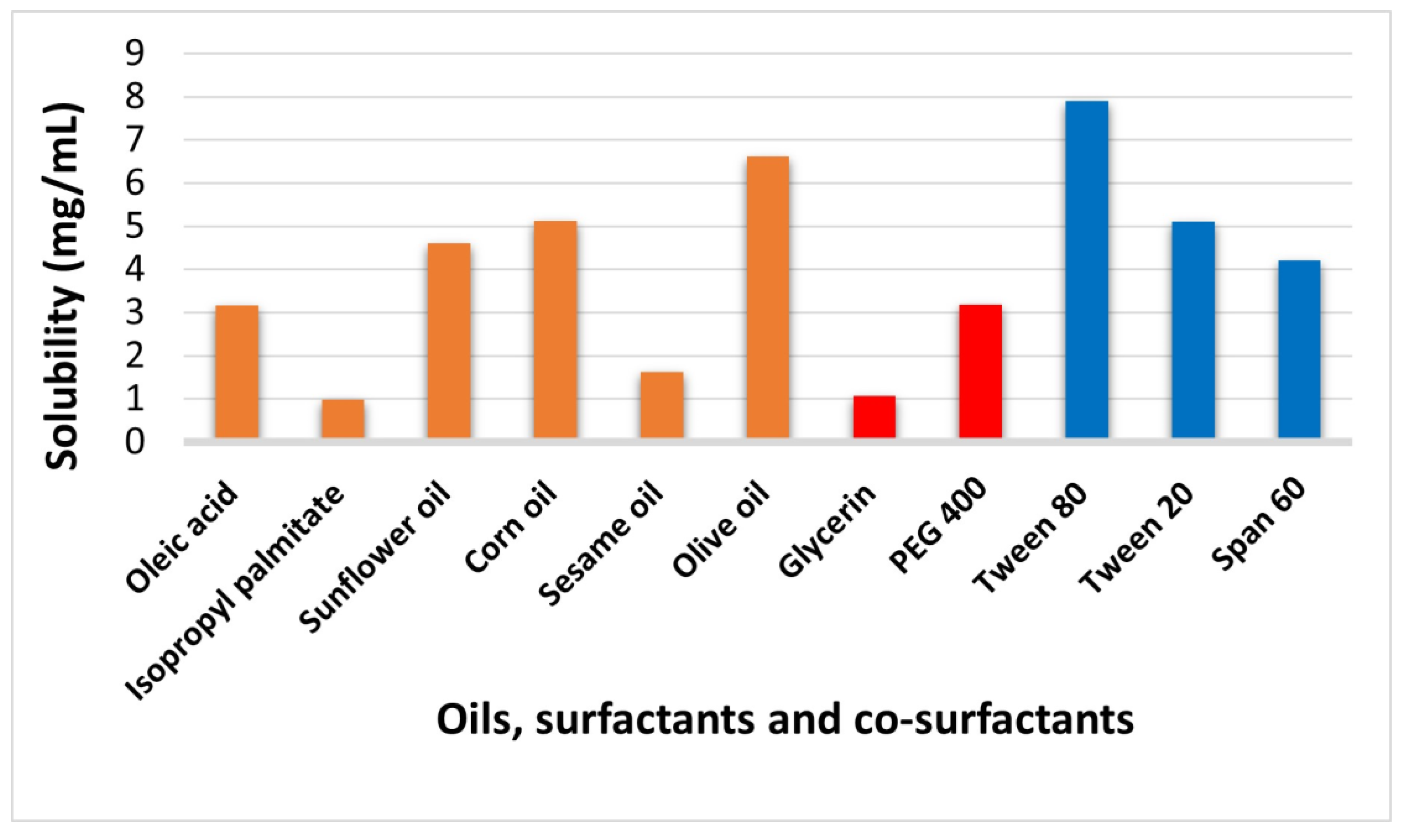

2.2. Saturation Solubility of P. pterocarpum Extract Using Different Oils, Surfactants, and Co-Surfactants

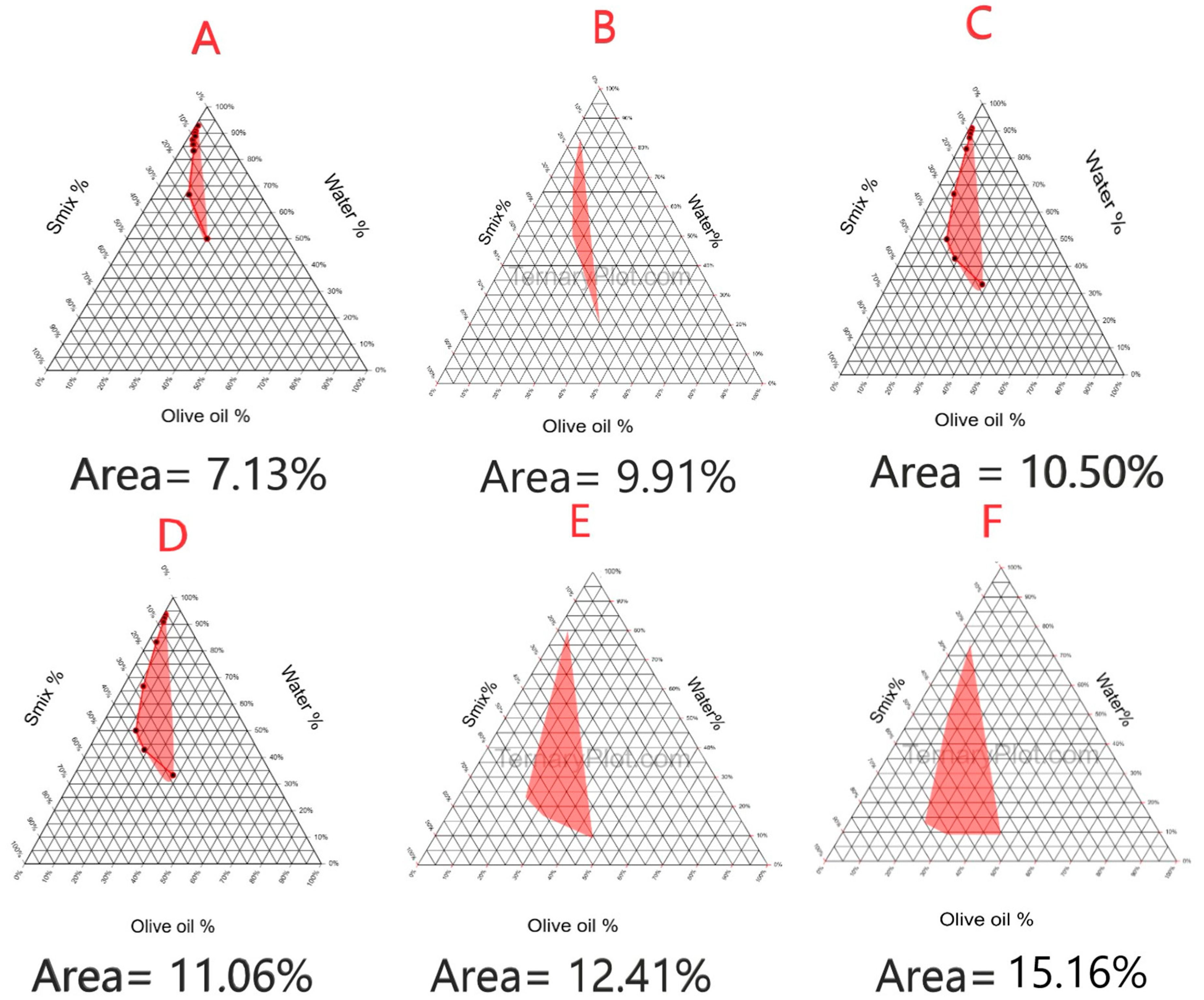

2.3. Construction of Pseudoternary Phase Diagram

2.4. Characterization of the Nanoemulsion

2.4.1. Percentage Transmittance, Dilution Test, Self-Emulsification Time, pH, and Viscosity

2.4.2. Determination of Drug Content, Droplet Size, Polydispersity Index (PDI), and Zeta Potential

2.5. TEM

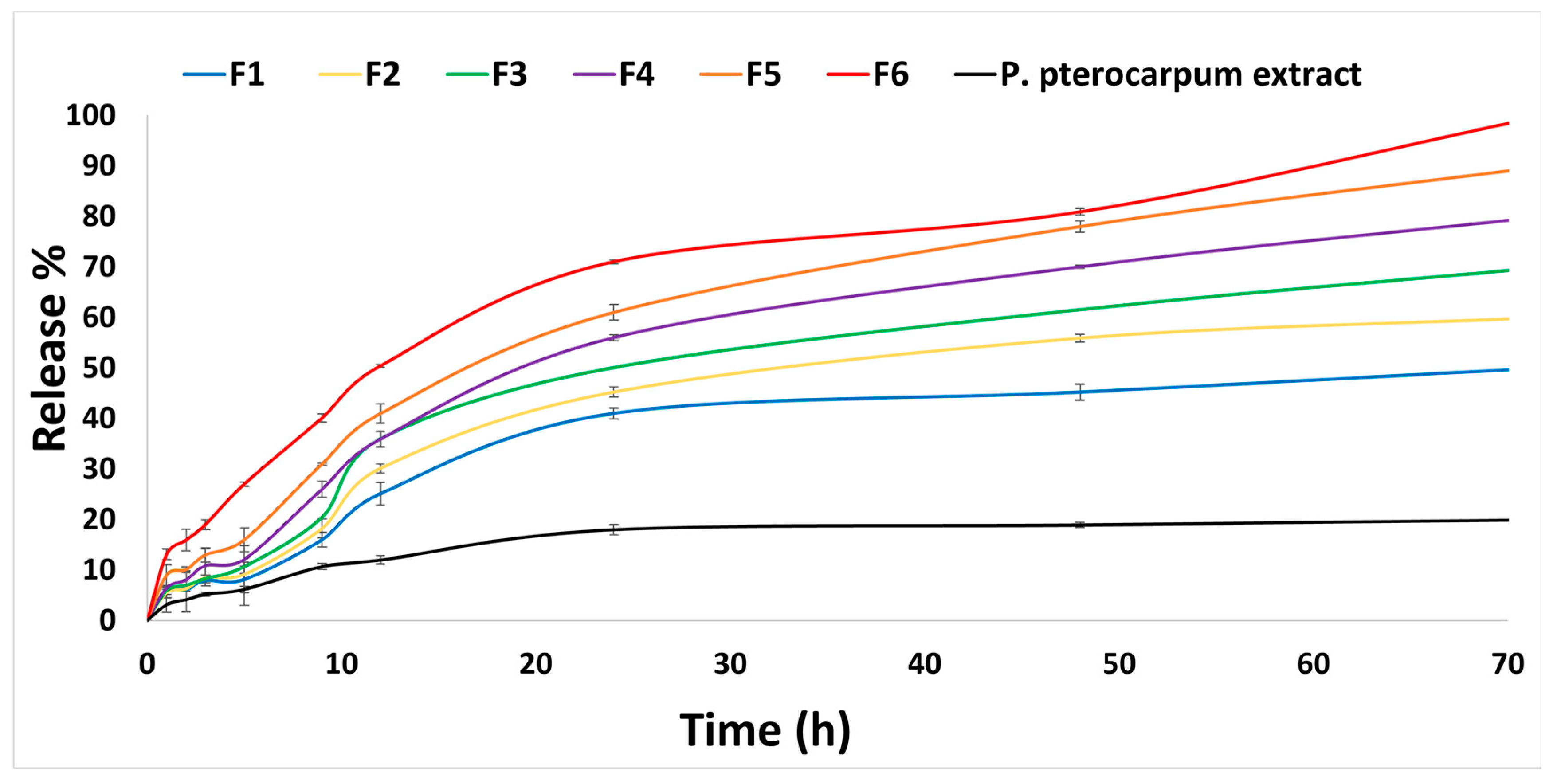

2.6. In Vitro Drug Release

2.7. Stability Study

2.8. In Vitro Hemolysis Assay

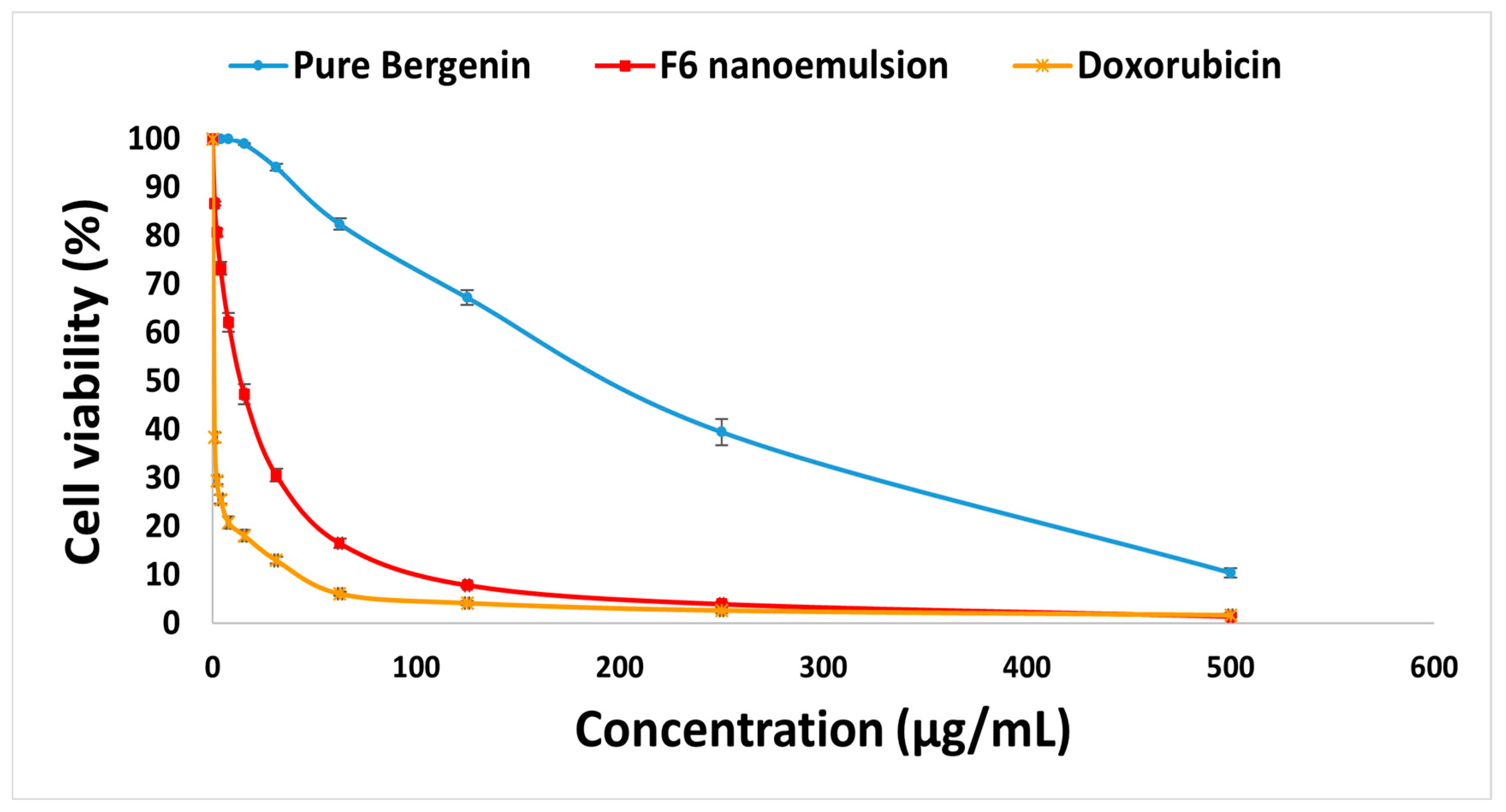

2.9. Cytotoxicity Evaluation Using Viability Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Plant Extraction and Isolation of Bergenin

3.3. Spectral Analysis (ES-MS, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, HSQC, and HMBC)

3.4. Standardization of P. pterocarpum Extract

3.5. Solubility of P. pterocarpum Extract in Different Oils, Surfactants, and Co-Surfactants

3.6. Construction of Pseudoternary Phase Diagram

3.7. Preparation of P. pterocarpum Extract-Loaded Nanoemulsion

3.8. Characterization of the Nanoemulsion Formulations

3.8.1. Percentage Transmittance, Dilution Test, and Self-Emulsification Time

3.8.2. pH and Viscosity Determination

3.8.3. Determination of Droplet Size, PDI, and Zeta Potential

3.8.4. Drug Content Measurement

3.8.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.9. In Vitro Drug Release

3.10. Stability Study

3.11. In Vitro Hemolysis Assay

3.12. Cytotoxicity Evaluation Using Viability Assay

3.13. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Smix | Surfactant to co-surfactant mixture |

| P. pterocarpum | Peltophorum pterocarpum |

| RFA | radiofrequency |

| MWA | microwave |

| TACE | trans-arterial chemoembolization |

| TARE | trans-arterial radioembolization |

| EASL | European Association for the Study of the Liver |

| AASLD | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases |

| BCLC | Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer |

| PDI | poly dispersibility index |

| DLC | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| HepG-2 cell line | human hepatocellular cancer cell line |

| OD | optical density |

| IC50 | The concentration needed to inhibit 50% of the cells |

References

- Mongalo, N.I.; Raletsena, M. Bioactive Molecules, Ethnomedicinal Uses, Toxicology, and Pharmacology of Peltophorum africanum Sond (Fabaceae): Systematic Review. Plants 2025, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.; Anand, A.; Hakkim, F.; Haq, Q. A review on phyto pharmacological aspects of Peltophorum pterocarpum (dc) baker ex. K heyne. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, F.O.; Khan, M.E.; Shehu, A.; Areh, E.T. Phytochemical analyses of extracts of the Peltophorum pterocarpum root bark and their anti-tyrosinase activities. J. Phytophamacol. 2025, 14, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Rizwani, G.H.; Shareef, H.; Cavar, S.; Zia-Ul-Haq, M. Assessment of total phenolic content and antioxidant potential of methanol extract of Peltophorum pterocarpum (DC.) Backer ex K. Heyne. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 26, 967–973. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Pancholi, B.; Jain, R. Peltophorum pterocarpum (DC.) Baker ex. K. Heyne flowers: Antimicrobial and antioxidant efficacies. Res. J. Med. Plants 2011, 5, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enechi, O.; Mbahotu, A.; Ikechukwu, U.R. Antibacterial Study of Flavonoid Extract of Peltophorum pterocarpum Stem Bark. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2016, 16, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monehin, J.A.; Oriola, A.O.; Olawuni, I.J.; Odediran, S.A.; Ige, O.O.; Idowu, T.O.; Ogundaini, A.O. Cholinesterase Inhibitory Compounds from Peltophorum pterocarpum Flowers. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 2899–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Xie, B.; Xie, K.; Liu, Q.; Sui, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, R.; Dai, J.; et al. Unravelling and reconstructing the biosynthetic pathway of bergenin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimo, Z.M.; Yakubu, M.N.; da Silva, E.L.; de Almeida, A.C.; Chaves, Y.O.; Costa, E.V.; da Silva, F.M.; Tavares, J.F.; Monteiro, W.M.; de Melo, G.C.; et al. Chemistry and Pharmacology of Bergenin or its derivatives: A promising molecule. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Lakhanpal, S.; Mahmood, D.; Kang, H.N.; Kim, B.; Kang, S.; Choi, J.; Moon, S.; Pandey, S.; Ballal, S.; et al. Bergenin, a bioactive flavonoid: Advancements in the prospects of anticancer mechanism, pharmacokinetics and nanoformulations. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1481587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, M.; Brandi, N.; Argalia, G.; Brocchi, S.; Farolfi, A.; Fanti, S.; Golfieri, R. Morphological, dynamic and functional characteristics of liver pseudolesions and benign lesions. Radiol. Med. 2022, 127, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, E.; de Castro, T.; Zeitlhoefler, M.; Sung, M.W.; Villanueva, A.; Mazzaferro, V.; Llovet, J.M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, A. Hepatology, E. Evolving global etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Insights and trends for 2024. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2024, 15, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Chan, S.; Dawson, L.; Kelley, R.; Llovet, J.; Meyer, T.; Ricke, J.; Rimassa, L.; Sapisochin, G.; Vilgrain, V.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals Oncol. 2025, 36, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.K.; Chong, M.C.; Gandhi, M.; Pokharkar, Y.M.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, L.; Lequn, L.; Chen, C.-H.; Kudo, M.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Real-world data on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific: The INSIGHT study. Liver Cancer 2024, 13, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Kaseb, A.; Elbaz, T.; El-Kassas, M.; El Fouly, A.; Hanno, A.F.; El Dorry, A.; Hosni, A.; Helmy, A.; Saad, A.S.; et al. Egyptian society of liver cancer recommendation guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2023, 10, 1547–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Yang, T.; Guo, X.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, P.; Guan, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; et al. CHB patients with rtA181T-mutated HBV infection are associated with higher risk hepatocellular carcinoma due to increases in mutation rates of tumour suppressor genes. J. Viral Hepat. 2023, 30, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, E.; Lee, H.M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2024: The multidisciplinary paradigm in an evolving treatment landscape. Cancers 2024, 16, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Wu, T.-C.; Lin, S.-M. Hepatocellular carcinoma systemic treatment update: From early to advanced stage. Biomed. J. 2024, 48, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, P.R.; Forner, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Mazzaferro, V.; Piscaglia, F.; Raoul, J.-L.; Schirmacher, P.; Vilgrain, V. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A.; et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Bruix, J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology 2003, 37, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R. Loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010, 52, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R.; Petruzzi, P.; Crocetti, L. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 30, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. The roles of doxorubicin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 1, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zeng, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, S.; Zheng, X.; Feng, W. Zingibroside R1 Isolated From Achyranthes bidentata Blume Ameliorates LPS/D-GalN-Induced Liver Injury by Regulating Succinic Acid Metabolism via the Gut Microbiota. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 4520–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahraa, G.; Balata, G.F. Formulation and in vitro characterization of nanoemulsions containing remdesivir or licorice extract: A potential subcutaneous injection for coronavirus treatment. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 234, 113703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, C. Precisely tailoring molecular structure of doxorubicin prodrugs to enable stable nanoassembly, rapid activation, and potent antitumor effect. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preeti; Sambhakar, S.; Malik, R.; Bhatia, S.; Al Harrasi, A.; Rani, C.; Saharan, R.; Kumar, S.; Geeta; Sehrawat, R. Nanoemulsion: An emerging novel technology for improving the bioavailability of drugs. Scientifica 2023, 2023, 6640103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, B.; Liu, T.-W.; Mei, H.-C.; Kuo, I.-C.; Surboyo, M.D.C.; Lin, H.-M.; Lee, C.-K.J. Herbal nanoemulsions in cosmetic science: A comprehensive review of design, preparation, formulation, and characterization. J. Food Drug Anal. 2024, 32, 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K. Herbal nanotechnology: Innovations and applications in modern medicine. Indian. J. Nat. Sci. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, M.K.; Chaerunisaa, A.Y.; Muhaimin, M.; Joni, I. Improved activity of herbal medicines through nanotechnology. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elufioye, T.O.; Obuotor, E.M.; Agbedahunsi, J.M.; Adesanya, S.A. Isolation and characterizations of Bergenin from Peltophorum pterocarpum leaves and its cholinesterase inhibitory activities. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2016, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, M.P.; Nunomura, S.M.; Lima, E.S.; Lima, A.S.; Almeida, P.D.d.; Nunomura, R.C. Quantification of bergenin, antioxidant activity and nitric oxide inhibition from bark, leaf and twig of Endopleura uchi. Quim. Nova 2020, 43, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, M.; Leri, M.; Nardiello, P.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Olive polyphenols: Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, Z.; Khoshkam, M.; Hamidi, M. Optimization of olive oil-based nanoemulsion preparation for intravenous drug delivery. Drug Res. 2019, 69, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.-N.; Dong, M.; Hou, Y.-Y.; Fan, G.; Pan, S.-Y. Effect of olive oil on the preparation of nanoemulsions and its effect on aroma release. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 4223–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Wadhwa, K.; Pahwa, R.; Ali, J.; Baboota, S. Screening of surfactant mixture ratio for preparation of oil-in-water nanoemulsion: A technical note. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 14, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musakhanian, J.; Osborne, D.W. Understanding Microemulsions and Nanoemulsions in (Trans) Dermal Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, A.; Rizwan, M.; Ahmad, F.J.; Iqbal, Z.; Khar, R.K.; Aqil, M.; Talegaonkar, S. Nanoemulsion components screening and selection: A technical note. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.M.; Basha, M.; Kamel, R. Nanoemulsions as parenteral drug delivery systems for a new anticancer benzimidazole derivative: Formulation and: In-vitro: Evaluation. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2015, 14, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shang, Z.; Gao, C.; Du, M.; Xu, S.; Song, H.; Liu, T. Nanoemulsion for solubilization, stabilization, and in vitro release of pterostilbene for oral delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.M.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Aziz, R.; Elmarzugi, N.A. The preparation and evaluation of self-nanoemulsifying systems containing Swietenia oil and an examination of its anti-inflammatory effects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 4685–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roethlisberger, D.; Mahler, H.-C.; Altenburger, U.; Pappenberger, A. If euhydric and isotonic do not work, what are acceptable pH and osmolality for parenteral drug dosage forms? J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorski, L.A.; Hagle, M.E.; Bierman, S. Intermittently delivered IV medication and pH: Reevaluating the evidence. J. Infus. Nurs. 2015, 38, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwa, A.; Jufri, M. Nanoemulsion curcumin injection showed significant anti-inflammatory activities on carrageenan-induced paw edema in Sprague-Dawley rats. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Arshad, M.U.; Imran, A.; Haroon Khalid, S.; Shah, M.A. Development, stabilization, and characterization of nanoemulsion of vitamin D3-enriched canola oil. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1205200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdany, A.T.; Saeed, A.M.; Alaayedi, M. Nanoemulsion and solid nanoemulsion for improving oral delivery of a breast cancer drug: Formulation, evaluation, and a comparison study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yati, K.; Amalia, A.; Puspasari, D. Effect of increasing concentrations of tween 80 and sorbitol as surfactants and cosurfactans against the physical stability properties of palm oil microemulsion. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 12506–12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.J.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhao, C.-X. Nanoemulsions for drug delivery. Particuology 2022, 64, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, C.; Partal, P.; Franco, J.M. Droplet-size distribution and stability of lipid injectable emulsions. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotta, S.; Khan, A.W.; Ansari, S.; Sharma, R.; Ali, J. Formulation of nanoemulsion: A comparison between phase inversion composition method and high-pressure homogenization method. J. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, P.L.; Sala, G.; Stieger, M.; Scholten, E. Clustering of oil droplets in o/w emulsions enhances perception of oil-related sensory attributes. Food Hydrocolloid 2019, 97, 105215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Kwon, S.; Gu, Z.; Selomulya, C. Stable nanoemulsions for poorly soluble curcumin: From production to digestion response in vitro. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 123720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguy, L.; Groo, A.-C.; Goux, D.; Hennequin, D.; Malzert-Fréon, A. Design of non-haemolytic nanoemulsions for intravenous administration of hydrophobic APIs. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, E.A.; Abd El-Hafeez, A.A.; Eldehna, W.M.; El Hassab, M.A.; Marzouk, H.M.M.; Elaasser, M.M.; Abou Taleb, N.A.; Amin, K.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Ghosh, P.; et al. Discovery of novel thiazolyl-pyrazolines as dual EGFR and VEGFR-2 inhibitors endowed with in vitro antitumor activity towards non-small lung cancer. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 37, 2265–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahramian, B.; Baygan, A.; Bostan, A. Preparation of O/W and W/O Nanoemulsions Based on Olive Oil and Investigation of Its Physicochemical Properties and Oxidative Stability. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2024, 43, 2259–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Kong, B.; Liu, Q.; Xia, X.; Liu, H. Characterization of nanoemulsions stabilized with different emulsifiers and their encapsulation efficiency for oregano essential oil: Tween 80, soybean protein isolate, tea saponin, and soy lecithin. Foods 2023, 12, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharmoria, P.; Bisht, M.; Gomes, M.C.; Martins, M.; Neves, M.C.; Mano, J.F.; Bdikin, I.; Coutinho, J.A.; Ventura, S.P. Protein-olive oil-in-water nanoemulsions as encapsulation materials for curcumin acting as anticancer agent towards MDA-MB-231 cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.E.; Lamprecht, A. Polyethylene glycol as an alternative polymer solvent for nanoparticle preparation. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 456, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAYAL, M.E.; Nasr, M.; Mortada, N.; Elkheshen, S.J.F. Optimization of the colloidal properties of different vesicular systems aiming to encapsulate (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Farmacia 2020, 68, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.M.; Gomaa, E.; Attia, M.S.; Abdelnaby, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.E.; Al-Harrasi, A.; El Deeb, S.; Al Ashmawy, A.Z.G. Albumin-Based Nanoparticles with Factorial Design as a Promising Approach for Remodeled Repaglinide: Evidence from In Silico, In Vitro, and In Vivo Evaluations. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, K.; Khan, M.F.A.; Alhodaib, A.; Ahmed, N.; Naz, I.; Mirza, B.; Tipu, M.K.; Fatima, H. Design and evaluation of pH-sensitive nanoformulation of bergenin isolated from Bergenia ciliata. Polymers 2022, 14, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-R.; Chuo, W.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.J.P. Optimization of formulation parameters in preparation of Fructus ligustri lucidi dropping pills by solid dispersion using 23 full experimental design. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya Rani, K.R.; Rajan, S.; Bhupathyraaj, M.; Priya, R.K.; Halligudi, N.; Al-Ghazali, M.A.; Sridhar, S.B.; Shareef, J.; Thomas, S.; Desai, S.M.J.P.; et al. The effect of polymers on drug release kinetics in nanoemulsion in situ gel formulation. Polymers 2022, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Shi, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, L.; Sun, K.; Li, Y. Relationship and improvement strategies between drug nanocarrier characteristics and hemocompatibility: What can we learn from the literature. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Clogston, J.D.; Neun, B.W.; Hall, J.B.; Patri, A.K.; McNeil, S.E. Method for analysis of nanoparticle hemolytic properties in vitro. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 2180–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, J.; Rotili, D.; Mai, A.; Steegborn, C.; Xu, S.; Jin, Z.G. SIRT6 protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in human pulmonary lung microvascular endothelial cells. Inflammation 2024, 47, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Veloso, D.M.; Barbosa, F.S.; de Oliveira, M.D.L.; de Oliveira, K.M.T.; de Almeida, P.D.O.; Lima, E.S. Evaluation of bergenin in amylase enzyme inhibition and lipid uptake in liver cells. Concilium 2023, 23, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Yasir, M.; Panda, D.S.; Singh, L. Bergenin nano-lipid carrier to improve the oral delivery: Development, optimization, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 96, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Roome, T.; Aziz, S.; Razzak, A.; Abbas, G.; Imran, M.; Jabri, T.; Gul, J.; Hussain, M.; Sikandar, B.; et al. Bergenin loaded gum xanthan stabilized silver nanoparticles suppress synovial inflammation through modulation of the immune response and oxidative stress in adjuvant induced arthritic rats. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 4486–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, N.; Sandeep, I.S.; Mohanty, S. Plant-derived natural products for drug discovery: Current approaches and prospects. Nucleus 2022, 65, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, W.H.; Abdelaziz, S.; Al Yousef, H.M. Chemical composition and biological activities of the aqueous fraction of Parkinsonea aculeata L. growing in Saudi Arabia. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, H.B.; Pramod, K.; Devanathan, R.; Sundaram, R. Use of bergenin as an analytical marker for standardization of the polyherbal formulation containing Saxifraga ligulata. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Huang, Y. Physicochemical properties of bergenin. Die Pharm.—Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 63, 366–371. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, S.; Chen, K.; Xu, L.; Wang, T.; Guo, C. Bergenin exerts hepatoprotective effects by inhibiting the release of inflammatory factors, apoptosis and autophagy via the PPAR-γ pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.J.; Alshetaili, A.; Aldayel, I.A.; Alablan, F.M.; Alsulays, B.; Alshahrani, S.; Alalaiwe, A.; Ansari, M.N.; Ur Rehman, N.; Shakeel, F. Formulation, characterization, in vitro and in vivo evaluations of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of luteolin. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2020, 14, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Mehta, S.; Mehta, A. Development and characterization of nanoemulsion as carrier for the enhancement of bioavailability of artemether. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2015, 43, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyavanandi, D.; Mandati, P.; Narala, S.; Alzahrani, A.; Kolimi, P.; Vemula, S.K.; Repka, M. Twin screw melt granulation: A single step approach for developing self-emulsifying drug delivery system for lipophilic drugs. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahraa, G.; Eissa, N.G.; El Nahas, H.M.; Balata, G.F. Fast disintegrating tablet of Doxazosin Mesylate nanosuspension: Preparation and characterization. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahraa, G.; Eissa, N.G.; Balata, G.F.; El Nahas, H.M. New Approach for Administration of Doxazosin Mesylate: Comparative Study between Liquid and Solid Self-nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 12, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, B.H.; Ahmed, H.Y.; El Gazzar, E.M.; Badawy, M. Enhancement the mycosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by using gamma radiation. Dose Response 2021, 19, 15593258211059323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayad, M.K.; Mowafy, H.A.; Zaky, A.A.; Samy, A.M. Chitosan caged liposomes for improving oral bioavailability of rivaroxaban: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2021, 26, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulmus, V.; Woodward, M.; Lin, L.; Murthy, N.; Stayton, P.; Hoffman, A. A new pH-responsive and glutathione-reactive, endosomal membrane-disruptive polymeric carrier for intracellular delivery of biomolecular drugs. J. Control Release 2003, 93, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangweni, N.F.; Dludla, P.V.; Chellan, N.; Mabasa, L.; Sharma, J.R.; Johnson, R. The implication of low dose dimethyl sulfoxide on mitochondrial function and oxidative damage in cultured cardiac and cancer cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomha, S.M.; Riyadh, S.M.; Mahmmoud, E.A.; Elaasser, M. Synthesis and anticancer activities of thiazoles, 1, 3-thiazines, and thiazolidine using chitosan-grafted-poly (vinylpyridine) as basic catalyst. Heterocycles 2015, 91, 1227–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Formula | Drug Content (%) | Droplet Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | PDI | Percentage Transmittance (%) | Dilution | Self-Emulsification Time (s) | pH | Viscosity (cP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 99.89 ± 0.06 | 253.26 ± 4.11 | −9.87 ± 0.45 | 0.225 | 100.03 ± 0.01 | √ | 13.11 ± 0.18 | 6.52 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.97 |

| F2 | 100.01 ± 0.01 | 145.36 ± 3.98 | −12.83 ± 1.45 | 0.209 | 99.99 ± 0.15 | √ | 15.23 ± 0.55 | 6.80 ± 0.17 | 0.73 ± 0.77 |

| F3 | 100.06 ± 0.11 | 121.65 ± 2.17 | −14.03 ± 3.99 | 0.204 | 100.01 ± 0.18 | √ | 17.88 ± 2.00 | 7.11 ± 0.77 | 0.69 ± 0.58 |

| F4 | 100.11 ± 0.05 | 89.50 ± 1.19 | −18.46 ± 5.71 | 0.219 | 99.89 ± 0.21 | √ | 21.55 ± 0.11 | 7.12 ± 0.81 | 0.61 ± 0.26 |

| F5 | 100.09 ± 0.11 | 70.11 ± 3.10 | −21.80 ± 1.11 | 0.251 | 100.00 ± 0.19 | √ | 25.11 ± 0.17 | 6.86 ± 0.32 | 0.59 ± 0.22 |

| F6 | 100.45 ± 0.99 | 50.12 ± 3.11 | −28.20 ± 2.90 | 0.229 | 100.01 ± 0.11 | √ | 29.64 ± 0.66 | 7.40 ± 0.18 | 0.57 ± 0.15 |

| Formula | Oil:Smix Ratio | Olive Oil (g) | Smix (g) | De-Ionized Water (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1:1 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.100 |

| F2 | 1:2 | 0.330 | 0.660 | 0.100 |

| F3 | 1:3 | 0.250 | 0.750 | 0.150 |

| F4 | 1:4 | 0.200 | 0.800 | 1.000 |

| F5 | 1:5 | 0.166 | 0.830 | 2.800 |

| F6 | 1:6 | 0.143 | 0.858 | 3.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Ashmawy, A.Z.G.; AbdelGhani, A.E.; Hassan, W.H.B.; El Weshahy, F.O.; Abdelmageed, W.M.; Al-Massarani, S.M.; Basudan, O.A.; Gamil, A.; El-Sayed, M.A. Unveiling the Cytotoxicity Potential of Nanoemulsion of Peltophorum pterocarpum Extract: A Natural Hemocompatible Injection Competing with Doxorubicin. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121818

Al Ashmawy AZG, AbdelGhani AE, Hassan WHB, El Weshahy FO, Abdelmageed WM, Al-Massarani SM, Basudan OA, Gamil A, El-Sayed MA. Unveiling the Cytotoxicity Potential of Nanoemulsion of Peltophorum pterocarpum Extract: A Natural Hemocompatible Injection Competing with Doxorubicin. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121818

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Ashmawy, Al Zahraa G., Afaf E. AbdelGhani, Wafaa H. B. Hassan, Fatma O. El Weshahy, Wael M. Abdelmageed, Shaza M. Al-Massarani, Omer A. Basudan, Aalaa Gamil, and May Ahmed El-Sayed. 2025. "Unveiling the Cytotoxicity Potential of Nanoemulsion of Peltophorum pterocarpum Extract: A Natural Hemocompatible Injection Competing with Doxorubicin" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121818

APA StyleAl Ashmawy, A. Z. G., AbdelGhani, A. E., Hassan, W. H. B., El Weshahy, F. O., Abdelmageed, W. M., Al-Massarani, S. M., Basudan, O. A., Gamil, A., & El-Sayed, M. A. (2025). Unveiling the Cytotoxicity Potential of Nanoemulsion of Peltophorum pterocarpum Extract: A Natural Hemocompatible Injection Competing with Doxorubicin. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121818