1. Introduction

Wound, a common skin injury, has a complex healing process involving hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

1]. During the proliferative phase, angiogenesis, driven by factors like VEGF and FGF from inflammatory cells and fibroblasts, is crucial. These factors stimulate new capillary growth, supplying the wound with oxygen, nutrients, and immune cells [

2]. The inflammatory phase involves platelets, macrophages, and neutrophils releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines to clear pathogens and debris [

3]. Collagen remodeling provides a scaffold for cell migration and proliferation. Its degradation products act as chemotactic signals for macrophages, modulating inflammation and angiogenesis [

4]. In the remodeling phase, type III collagen is gradually replaced by type I collagen to strengthen the wound [

5]. These interconnected processes collectively determine the efficiency and quality of wound healing.

Shengji Yuhong Ointment (SJYHO), a traditional Chinese medicine, promotes wound healing by detoxifying, reducing swelling, forming new tissue, and alleviating pain [

6]. It stimulates granulation tissue growth and improves microcirculation, providing essential blood supply for healing. Its components, such as

Lithospermum erythrorhizon Siebold & Zucc. and

Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., have antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties that curb bacterial growth, reduce inflammation, lower infection risk, and enhance immune function by activating lymphocytes [

7,

8]. The ointment also regulates growth factors like bFGF, FGF, EGF, PDGF, TGF-β, and VEGF. In the early wound healing phase, it promotes angiogenesis and fibroblast proliferation. During the remodeling phase, it reduces bFGF levels to promote collagen degradation and inhibits angiogenesis to minimize scarring [

9,

10]. Additionally, it inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 to create a favorable healing environment [

11]. By facilitating epithelial cell growth and collagen synthesis, SJYHO accelerates wound repair and strengthens the wound [

9]. However, the specific targets and mechanism by which SJYHO promotes wound healing have not yet been reported.

Glycyrrhizic acid, a pentacyclic triterpenoid from glycyrrhiza, has broad pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-tumorigenesis, and immune regulation [

12]. It inhibits COX and LOX, reducing prostaglandin and leukotriene production, and suppresses the NF-κB pathway to lower pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, thus easing inflammation and creating a favorable environment for wound healing [

13,

14]. Glycyrrhizic acid modulates the immune response by enhancing macrophage phagocytosis, promoting lymphocyte proliferation, and balancing Th1/Th2 cells, thereby bolstering the body’s immune defense and aiding wound repair [

15,

16]. It also combats oxidative stress, further supporting tissue recovery [

17]. Glycyrrhizic acid is formulated into various products, including injectables (e.g., diammonium glycyrrhizate and compound glycyrrhizin injections), orals (e.g., diammonium glycyrrhizate capsules and compound glycyrrhizin tablets), topicals (e.g., glycyrrhizic acid gels), and glycyrrhizic acid tablets [

18]. Potassium glycyrrhizate and other glycyrrhizic acid-based drugs promote granulation tissue formation and fibroblast proliferation. They also speed up re-epithelialization and angiogenesis, collectively accelerating wound healing [

19].

All kinds of trauma can cause wounds and trigger an immune response to repair the damage. Without timely treatment, serious physical complications may occur [

20]. SJYHO is used to promote wound healing. However, its use requires caution due to potential allergy risks and possible long-term toxicity. Previous studies have primarily described the phenotypic effects of SJYHO, but a systems-level understanding of its key bioactive ingredients and their specific cellular targets is critically needed. To address this, our study employed an integrated strategy combining network pharmacology and machine learning to systematically identify the core active compound and its primary target from the complex mixture of SJYHO. We further sought to translate this discovery into a simplified, target-specific hydrogel formulation. This study explores its therapeutic mechanisms to develop new wound-healing drugs. Based on these mechanisms, the study finds and reveals how glycyrrhizic acid-based composite gels (GA-Gel) aid wound repair.

3. Discussion

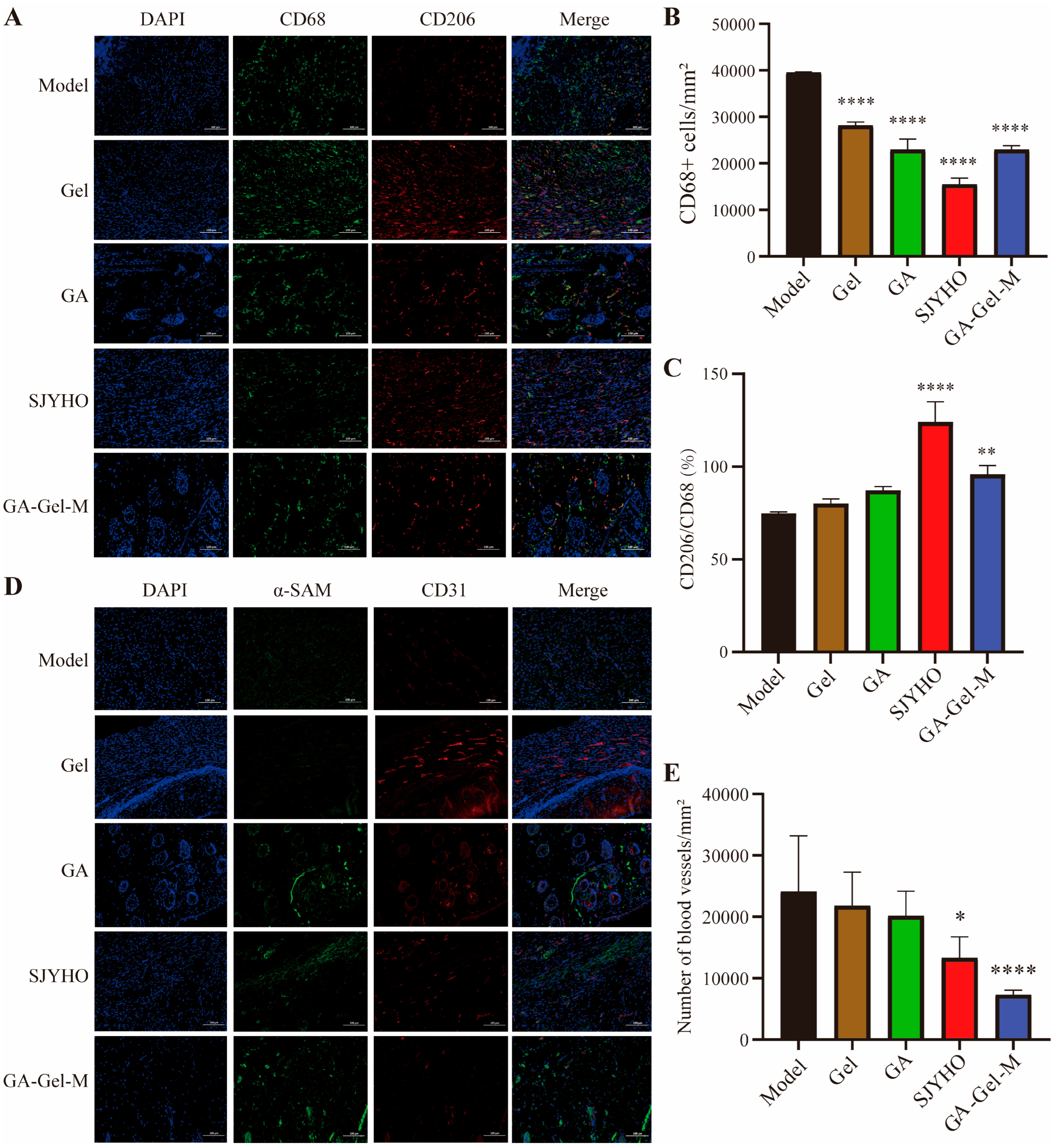

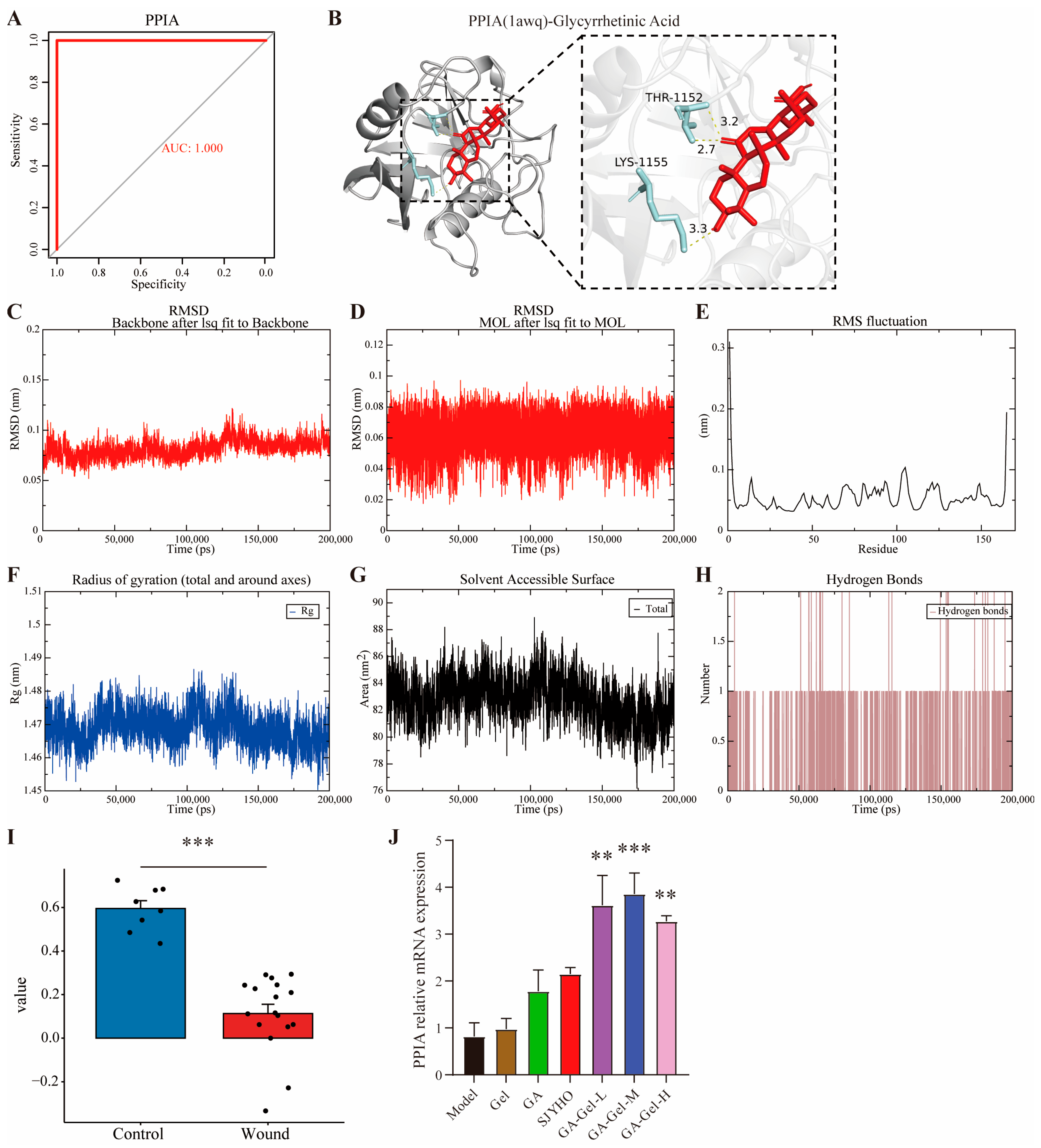

SJYHO is used clinically for wounds like acne, burns, diabetic foot ulcers, and pressure ulcers. Network pharmacology suggests PPIA and glycyrrhizic acid are key for its healing effects. When formulated into a composite gel (GA-Gel), animal studies confirm it accelerates wound healing by reducing inflammation, inhibiting late-stage angiogenesis, alleviating pain, and enhancing collagen deposition. PPIA likely mediates wound immune infiltration by regulating CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, and memory B cells. Importantly, GA-Gel achieves these effects by targeting PPIA.

Glycyrrhizic acid has been shown to significantly enhance wound healing. They exhibit potent anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities [

21], which help in reducing inflammation and preventing infections at the wound site. Glycyrrhizic acid can form hydrogels that create a moist environment conducive to efficient wound healing. These hydrogels, when combined with other materials like carboxymethyl chitosan, not only improve the mechanical properties and stability of the wound dressing but also promote angiogenesis and tissue regeneration [

22]. Furthermore, glycyrrhizic acid has been found to suppress wound inflammation, promote the formation of new granulation tissue, and stimulate tissue re-epithelialization [

23]. It also aids in the absorption of wound exudates and accelerates the healing process by promoting cell proliferation and migration [

24]. Overall, glycyrrhizic acid has shown great potential in promoting wound healing and tissue regeneration. Glycyrrhizic acid is used in medicine and as a natural sweetener and preservative in foods like candies, beverages, and ice creams. Its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties also make it useful in cosmetics for skin-whitening, freckle-removing, and anti-allergy products. Overall, glycyrrhizic acid has broad applications and promising prospects across these fields.

Immune cells play an important role in wound healing. Neutrophils are the first to arrive, clearing pathogens and debris via phagocytosis and releasing enzymes/ROS. Their activity peaks early and declines as healing progresses [

25]. Macrophages transition from pro-inflammatory (M1) to anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes [

26]. CD4

+ T cells (helper T cells) modulate the immune response by differentiating into subsets, which help activate B cells and macrophages [

27]. CD8

+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells) eliminate infected or damaged cells [

28]. In summary, immune cells act at different stages of wound healing to ensure efficient tissue repair. Their balanced activity is crucial for proper wound healing, and imbalance can lead to impaired healing or chronic inflammation. Studies show that PPIA expression is negatively correlated with immune checkpoint levels in B cells, CD4

+ T cells, CD8

+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, suggesting a role for PPIA in modulating these cells’ functions [

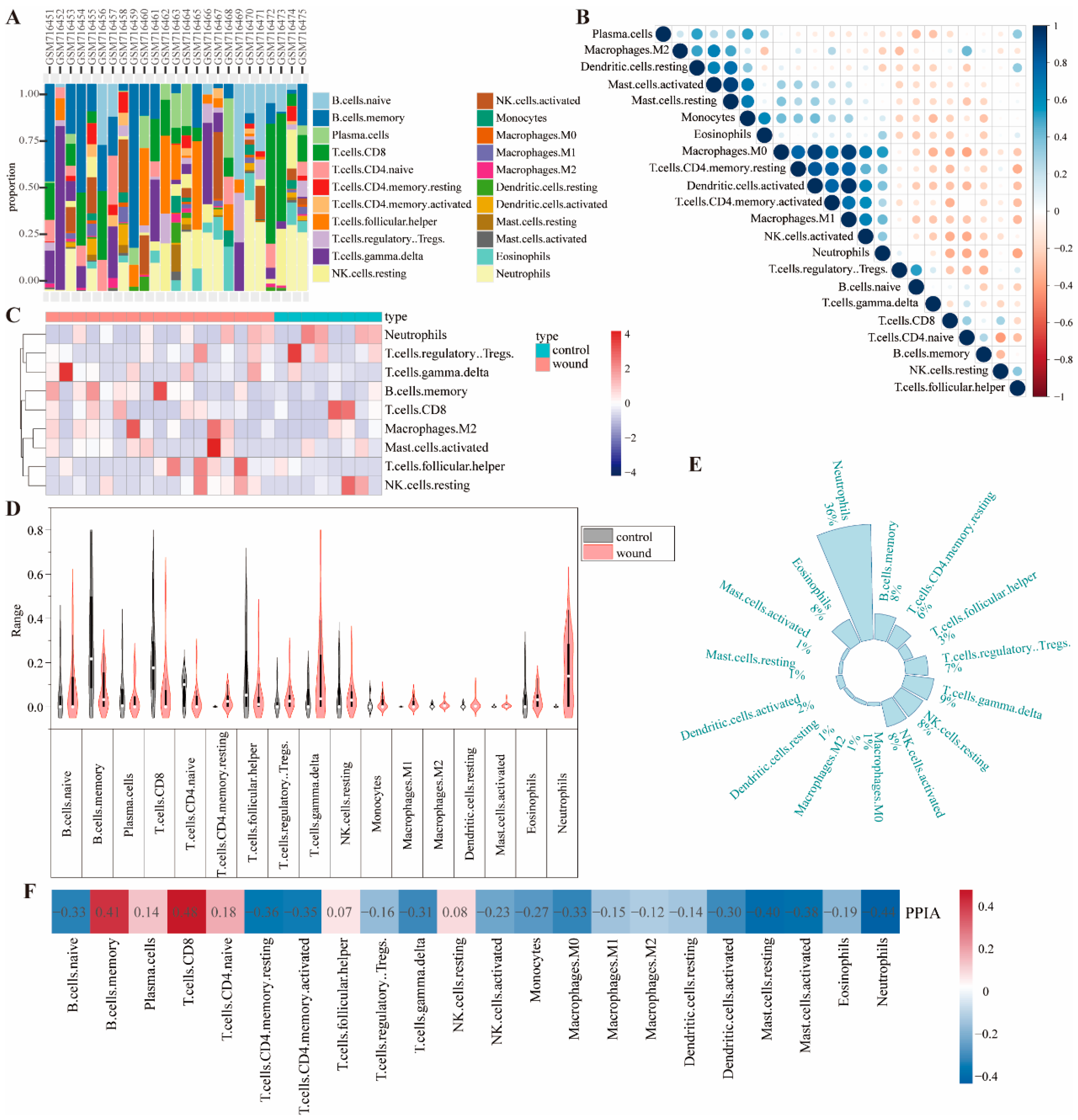

29]. Our research found that neutrophils are the most prevalent immune cells in wound sites, followed by T cells, and that PPIA exhibits strong correlations with CD8

+ T cells and neutrophils during wound healing.

Glycyrrhizic acid modulates immune cells to reduce inflammation and promote tissue repair [

23]. It inhibits neutrophil infiltration and activation by suppressing inflammatory mediators, reducing tissue damage. In macrophages, it downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) and upregulates anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10), enhancing phagocytic activity and promoting the M2 phenotype for tissue repair. In T lymphocytes, it suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IFN-γ), promotes regulatory T-cell differentiation, and enhances inhibitory receptor expression, preventing excessive immune responses and tissue damage. Overall, glycyrrhizic acid balances immune responses to facilitate wound healing. Glycyrrhizic acid has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects and may enhance its efficacy by interacting with PPIA. It might target the PPIA protein to regulate CD8

+ T cells and neutrophils, mediating the inflammatory phase of wound healing.

Wound healing begins as fibroblasts migrate to the wound site, producing collagen and other extracellular matrix components. Angiogenesis supplies the wound with oxygen and nutrients. As collagen and the matrix remodel, the wound’s structure and function gradually restore, with tensile strength increasing over time. PPIA protein may influence extracellular matrix remodeling by affecting collagen folding [

29]. Our study shows that glycyrrhizic acid affects collagen remodeling and inhibits late-stage wound angiogenesis, likely by targeting PPIA protein, thus accelerating scar-free wound healing. Gel formulations offer several benefits for wound healing [

30], so we prepared glycyrrhizic acid into a compound gel, which is beneficial for wound healing.

While our study confirmed the pivotal involvement of PPIA, its role as a multifunctional signaling hub suggests it orchestrates healing by modulating key pathways. Based on established literature, we propose that PPIA likely mediates GA-Gel’s effects through coordinated regulation of the NF-κB, MAPK, and TGF-β pathways. Firstly, the accelerated inflammation resolution observed in our model can be plausibly explained by PPIA’s documented interaction with the NF-κB pathway. Extracellular PPIA is known to activate NF-κB signaling via its receptor CD147 [

31,

32]. However, the precise temporal modulation of this axis is crucial. We hypothesize that GA-Gel-induced PPIA may contribute to a negative feedback mechanism that fine-tunes and ultimately dampens NF-κB activation, thereby preventing excessive inflammation and facilitating the transition to the proliferative phase. This aligns perfectly with our observed reduction in pro-inflammatory markers. Secondly, the robust promotion of cell proliferation and re-epithelialization strongly implies the involvement of the MAPK/ERK cascade. Literature firmly establishes that the PPIA-CD147 complex is a potent upstream activator of ERK1/2 signaling [

31]. It is therefore a reasonable inference that GA-Gel, through upregulating PPIA, potentiates the MAPK/ERK pathway, thereby driving the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and keratinocytes to accelerate tissue repair. Furthermore, the enhanced collagen deposition and improved tissue remodeling we documented are hallmarks of activated TGF-β signaling. PPIA has been identified as an enhancer of TGF-β signal transduction [

33]. Consequently, we postulate that PPIA serves as the critical link whereby GA-Gel amplifies the TGF-β1 pathway, promoting fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts and subsequent extracellular matrix synthesis. In summary, we propose an integrative model wherein GA-Gel, via the central signaling node PPIA, acts as a molecular conductor to synergistically temper NF-κB-driven inflammation, propel MAPK/ERK-mediated proliferation, and augment TGF-β-dependent tissue remodeling. This multi-targeted action provides a compelling theoretical foundation for GA-Gel’s efficacy and underscores PPIA’s role as a key coordinator in the healing process, directly addressing the reviewer’s insightful comment.

4. Methods

4.1. The Target of SJYHO

Use the TCM Integrative Pharmacology Research Platform (TCMIP 2.0) at

http://www.tcmip.cn (accessed on 11 August 2025), and select the herbs “Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.”, “Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm.) Benth. & Hook. f. ex Franch. & Sav.”, “Angelica sinensis (Oliv.)Diels”, “Lithospermum erythrorhizon Siebold & Zucc.” and “Resina Draconis” to collect active components and relevant targets of SJYHO. Retrieve SMILES sequences from PubChem, and use SwissTargetPrediction (

http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch (accessed on 11 August 2025)) by selecting “Homo sapiens” and “Probability > 0”. Obtain MOL2 component files from the Traditional Chinese Medicine System Pharmacology Database (TCMSP) at

https://www.tcmsp-e.com/ (accessed on 11 August 2025) and use Pharmmapper (

https://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025)) to predict targets by selecting “Human protein targets only”. Convert results to “Gene Name” via the UniProt database at

https://www.uniprot.org (accessed on 11 August 2025). Finally, integrate and deduplicate to obtain potential drug targets.

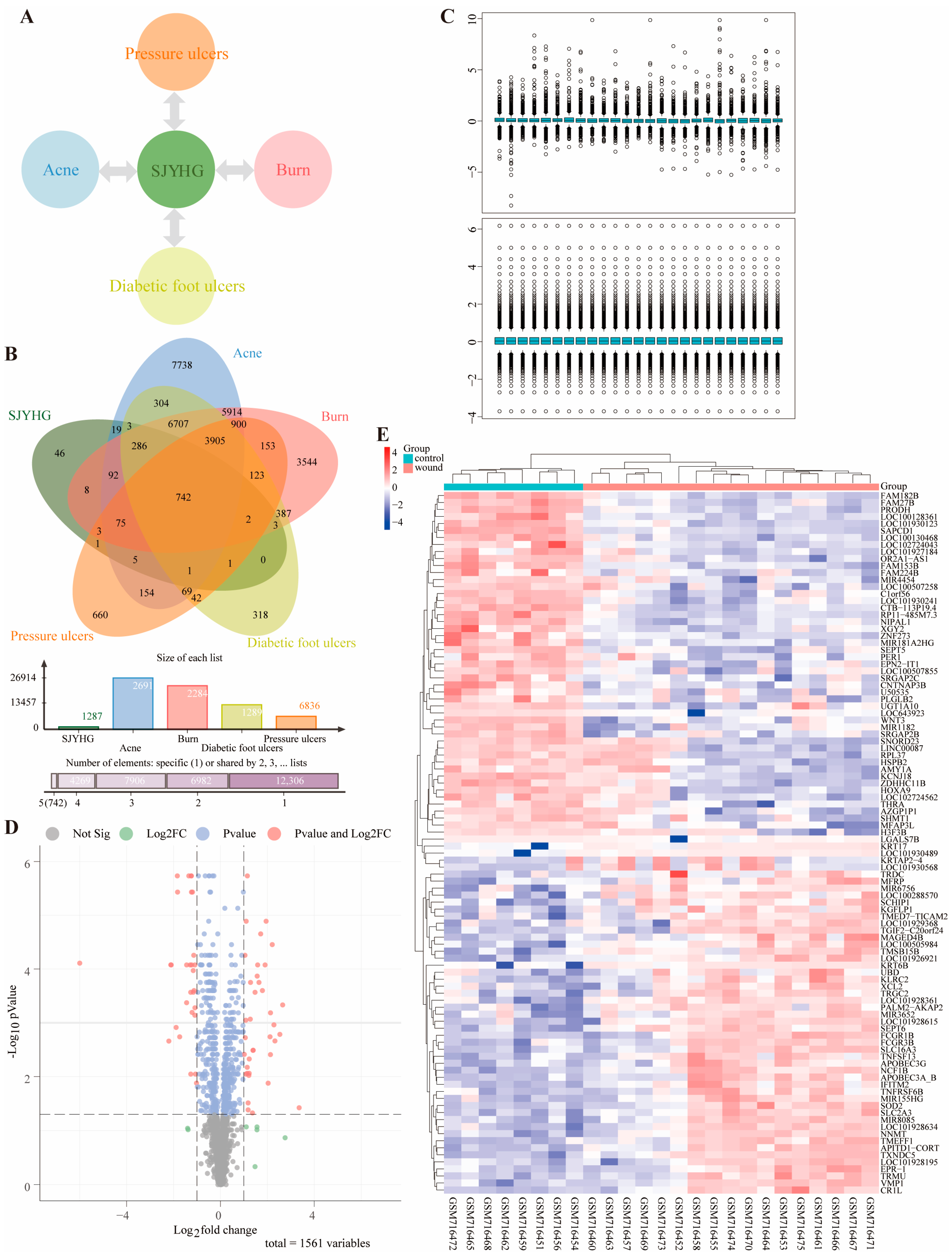

4.2. Targets Related to the Indications of SJYHO

Search GeneCards (

https://www.genecards.org (accessed on 11 August 2025)) and CTD (

https://ctdbase.org (accessed on 11 August 2025)) databases for targets related to Acne, Burns, Pressure ulcers, and Diabetic foot ulcers. Consolidate these targets to obtain disease-related ones. Use Wei Sheng Xin (

https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn (accessed on 11 August 2025)) to find the intersection between disease targets and SJYHO targets, and visualize the drug–disease relationship with a radiation diagram.

4.3. Analysis of Wound-Related Targets

Search GEO (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (accessed on 11 August 2025)) for wound-related datasets. In Rstudio2025.05.01, use the limma package for data cleaning, apply normalizeBetweenArrays for standardization, identify differentially expressed genes with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and control the FDR using Benjamini–Hochberg. Set |logFC| > 3 and FDR < 0.3 as the criteria. Present results via volcano plots and heatmaps.

4.4. Analysis of Immune Infiltration

Utilize the CIBERSORT algorithm in R to conduct immune cell infiltration analysis on genomic data. Use the LM22 signature matrix to deconvolve the data and calculate the abundance of 22 immune cell types. Visualize the infiltration levels by creating scatter plots, heatmaps, and stacked bar charts. Additionally, use Origin 2025 to draw violin plots for immune infiltration. Based on the CIBERSORT results, filter wound-healing samples, compute the median expression of immune cells, and plot a pie chart to show their overall expression in these samples.

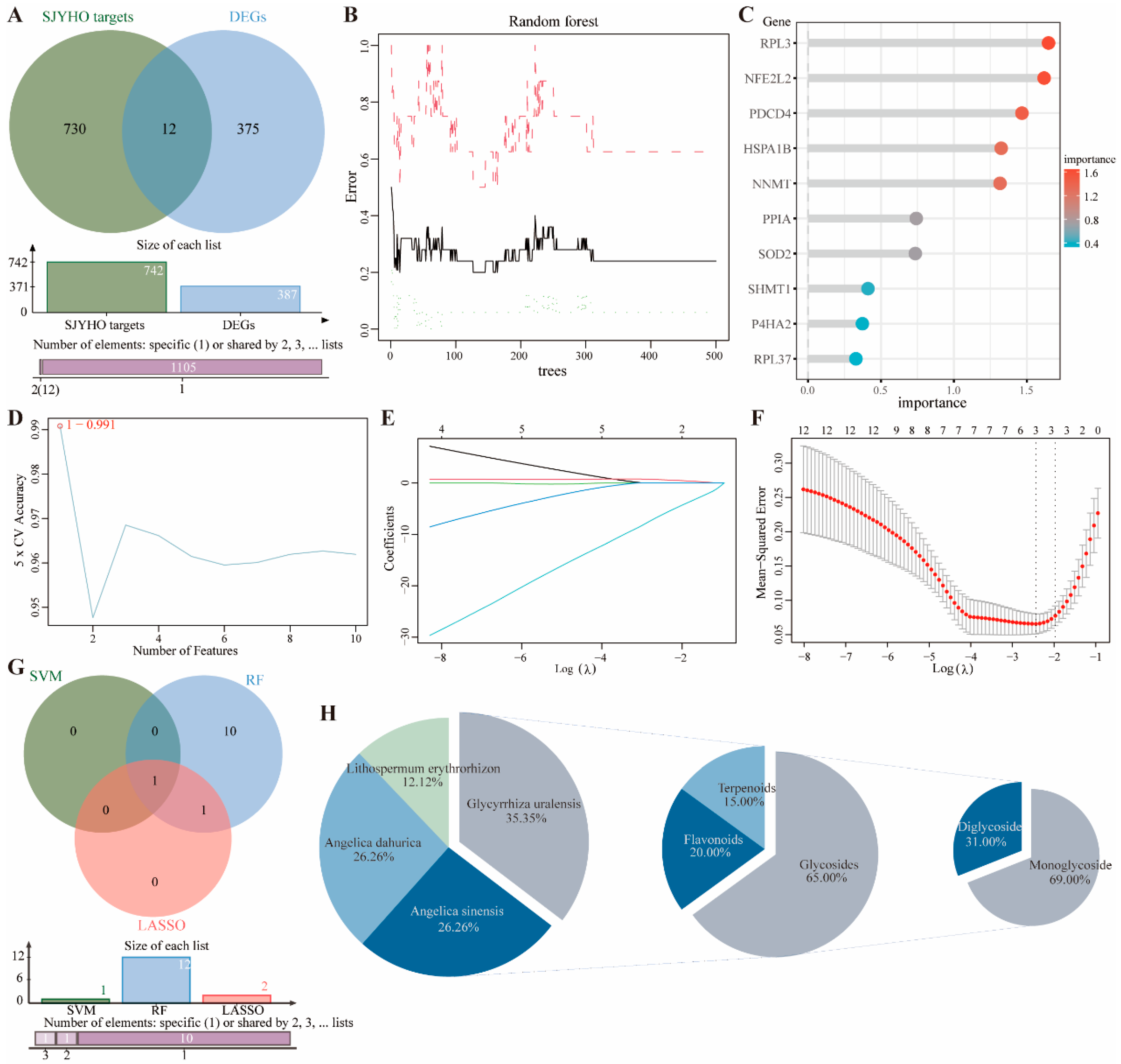

4.5. Machine Learning

Intersect the potential targets of SJYHO with GEO-identified differentially expressed genes to obtain the intersected genes. Then, perform dimensionality reduction on these genes using three machine learning methods: SVM-RFE, random forest, and LASSO. SVM-RFE: Use a five-fold cross-validation framework to assess feature importance. Determine the optimal feature subset via feature-number scanning and plot error rate vs. accuracy. Random Forest: Build a classification model with the randomForest package. Generate a random forest plot and rank genes by importance. LASSO: Confirm the best regularization parameter λ using five-fold cross-validation. Plot the cross-validation results to show MSE and standard error for different λ values. Extract λ.min and λ.1se, fit the LASSO regression path, and plot the path.

4.6. Component Backtracking of Core Targets

Identify core genes by intersecting genes screened via the three machine learning methods. Trace these core genes back to drug components. Integrate and classify the components hierarchically by TCM categories and compound types. Import the data into Wei Sheng Xin (

https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn (accessed on 15 August 2025)) to create a pie chart showing the proportion of drug components. Select the most critical potential components for the experiment.

4.7. Preparation of Glycyrrhizic Acid-Containing Composite Gel

Glycyrrhizic acid was purchased from Chengdu Push Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China (catalog no. PU0054-0025). Sodium diclofenac gel was obtained from Shenyang Luzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shenyang, China (catalog no. H19990010). SJYHO was from Huangshan Huibintang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Huangshan, China (catalog no. Wan GZ WZ 2015000527).

Accurately weigh carboxymethyl cellulose, xanthan gum, and glycerol using a balance, moisten them by stirring, and gradually add distilled water while continuously stirring with a glass rod. Grind for about an hour to allow the gel to fully swell. Add triethanolamine and continue grinding, then add glycyrrhizic acid, sodium hyaluronate, 1,2-hexanediol, 1,2-octanediol, and 1,3-butanediol. Stir until a gel forms. Glycyrrhizic acid concentration, determined by prior research, is divided into three groups: 5% (GA-Gel-L), 10% (GA-Gel-M), and 15% (GA-Gel-H). The blank glycyrrhizic acid (GA) group is made by mixing 8.5 mL distilled water with 1.5 g glycyrrhizic acid. The blank gel (Gel) group is the water gel without glycyrrhizic acid. After the preparation is completed, let the gel stand out of light to remove air bubbles. Among them, the dosage of carbomer, xanthan gum, compound humectant and triethanolamine was optimized through single-factor response surface experiments, and stability tests (properties, Ph, heat resistance, cold resistance, humectability, sensory evaluation, etc.) were passed to ensure the best performance of the gel agent.

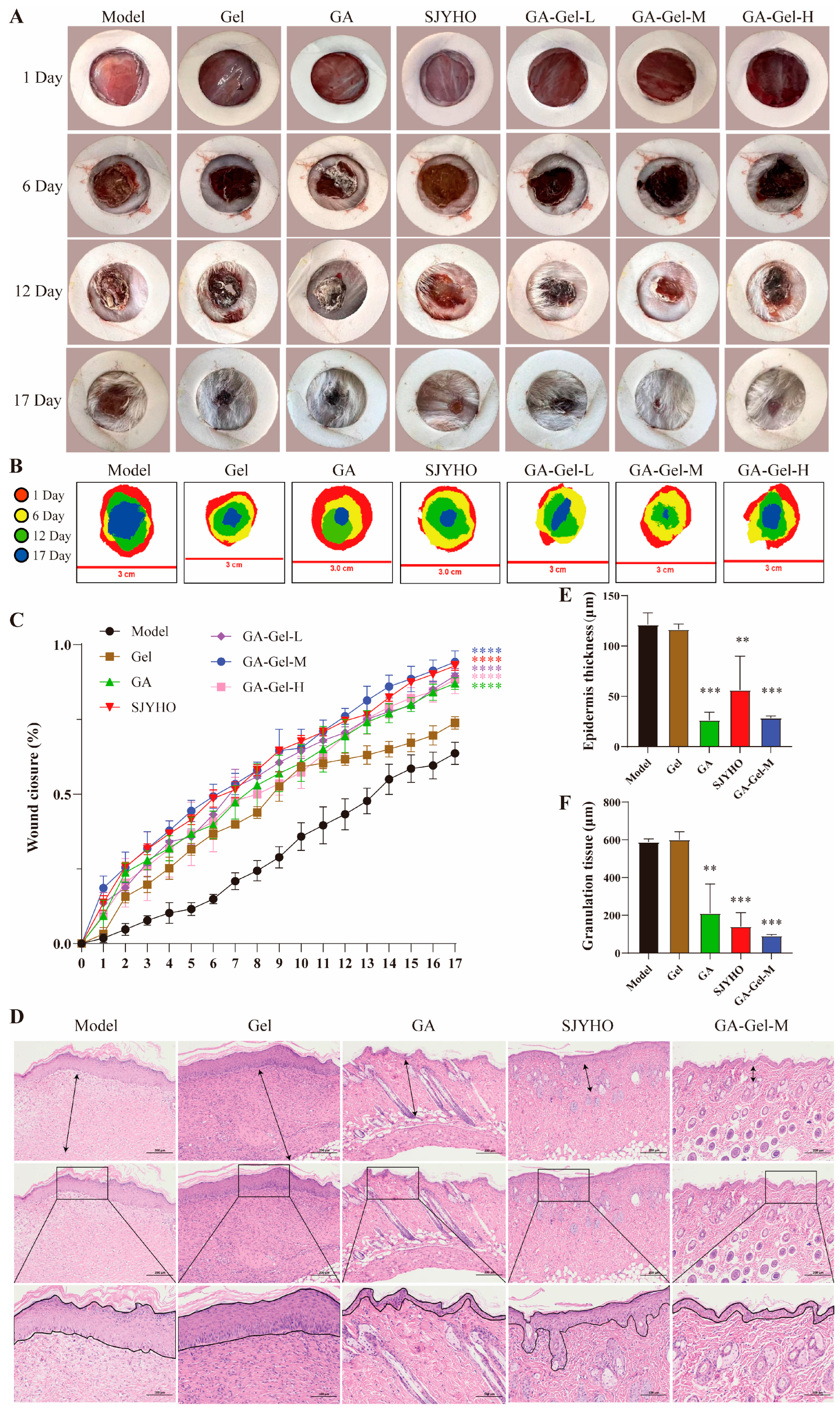

4.8. Wound Repair Experiment of Mice

Male BALB/c mice (20.0 ± 2.0 g, 6 weeks old) were purchased from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (License No.: SCXK (Jing) 2019-0010). Mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee of Shanxi University of Chinese Medicine (the permission number: AWE202503313), and the laws of animal experiments were strictly observed. Mice were housed in a controlled environment (25 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 5% humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to food and water for a week.

Mice were randomly divided into seven groups: Control group, GA group, Gel group, SJYHO group, GA-Gel-L group, GA-Gel-M group, and GA-Gel-H group, with six mice per group. After ether anesthesia, depilate the back skin, punch a 15.0 mm full-thickness skin defect, and dress with sterile gauze. House mice individually. The Control group receives 0.5 g of distilled water, while the other groups receive 0.5 g of respective drugs. Administer drugs twice daily for 17 days. Monitor mice for hair, movement, and eating changes. Cover the wound with PU membrane, take photograph, draw the outline, and measure the wound area using ImageJ 1.54p. Calculate the healing rate: [(Original area-unhealed area)/Original area] × 100%. Use GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 to draw line charts and conduct two-way ANOVA.

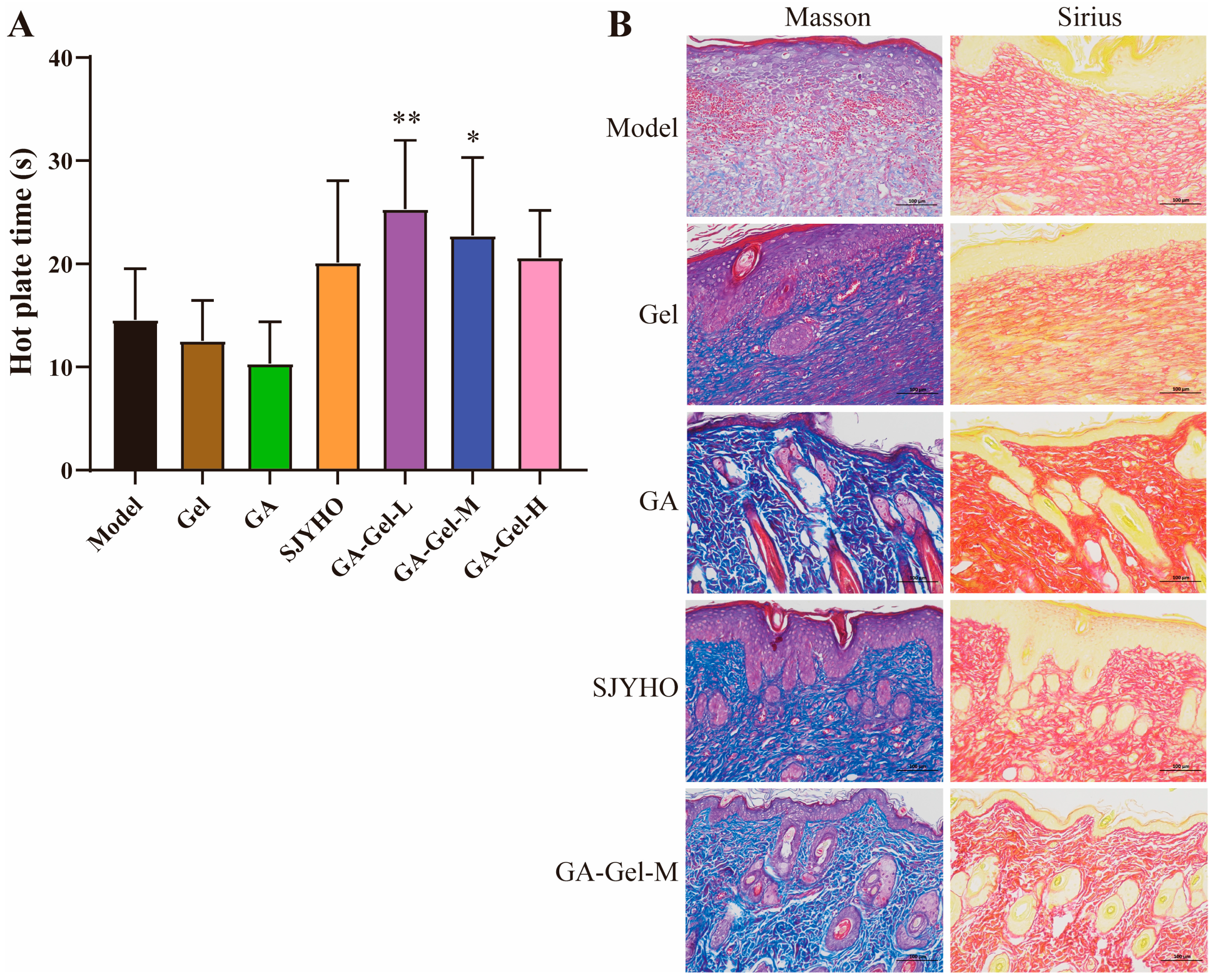

4.9. Histopathological Examination

On day 17 post-surgery, collect the wounded skin, fix it in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embed it in paraffin. Slice the embedded samples into 5 μm thick sections, and stain them with Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, and Sirius Red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Use H&E staining to evaluate granulation tissue formation and re-epithelialization, and quantify the granulation tissue and epithelium regeneration using ImageJ. Analyze collagen deposition and the ratio of types I and III collagen using Masson’s trichrome and Sirius Red staining.

To assess angiogenesis on day 17 post-surgery, perform immunofluorescence (IF) staining with CD31 (1:200, ab32457, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) and α-SMA (1:200, ab5831, Abcam, USA) antibodies. To evaluate the inflammatory response on day 17 post-surgery, conduct IF staining with CD68 (1:200, ab201340, Abcam, USA) and CD206 (1:200, Ab64693, Abcam, USA) antibodies for macrophages and M2-macrophages. Stain cell nuclei with DAPI.

Acquire IF and immunohistochemical images using a confocal microscope (Olympus FV10 inverted microscope, Tokyo, Japan) and an inverted microscope (Axio Vert A1, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Quantify the results with ImageJ and plot bar charts using GraphPad Prism 10.4.1. Perform one-way ANOVA to analyze significant differences.

4.10. Analgesia Experiment

Place mice on a heat plate preheated to 55 °C (±0.5 °C) at 25 °C room temperature. The time from contact with the hot plate to licking the hind paw was used as the pain threshold. Select mice with thresholds of 5–30 s. Measure pre-drug thresholds, then post-drug thresholds. Record the data, import it into GraphPad Prism 10.4.1, plot bar charts, and conduct one-way ANOVA for significant difference analysis.

4.11. Correlation Analysis

To clarify the role of immune cells in the sample, the CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm was used to calculate the relative abundance of 22 immune cells. Then, the Spearman rank-correlation coefficient matrix between immune cell abundance and gene expression was calculated. The correlation between core genes and immune cells was visualized using a heatmap. The pROC package in R was used to plot the ROC curve and calculate the area under the curve (AUC) value.

4.12. Molecular Docking

First, obtain the sequence of the PPIA protein from the UniProt database. Then, use the sequence name to download the crystal structure from the PDB database (

https://www.rcsb.org (accessed on 25 August 2025)). Retrieve the three-dimensional structure of glycyrrhizic acid from the PubChem database. Optimize the protein receptor and small-molecule ligand through a stepwise pre-processing procedure. Use AutoDockTools 1.5.7 to remove water molecules from the target protein and add hydrogen atoms, saving it as the receptor file. Import the small molecule into OpenBabel version3.1.1 and convert it to PDB format. Then, use AutoDockTools to add hydrogen atoms, assign molecular charges, and set the grid parameters for the docking area, generating a Vina-dedicated configuration file. Perform 10 independent docking calculations using AutoDock Vina to explore the best binding mode between the ligand and receptor. Screen for the lowest binding energy, retain the protein conformation with the optimal binding energy, and save it in PDB format. Visualize the best binding state of the ligand and receptor using PyMol version3.1.4.1 and analyze the ligand–receptor interaction pattern.

4.13. Molecular Dynamic

Use AlphaFold to remodel the protein receptor. Use PyMol to restore the protein position and convert it to standard PDB format. Complete the hydrogen atoms of the small molecule and save it as mol2 format. Generate molecular topology files using Sobtop1.0 software. Build the simulation system with GROMACS2020.6: create a water box model, parameterize with the AMBER99SB force field, solvate the system using the SPC water model, and neutralize the system by adding ions. Perform energy minimization using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient methods for 10,000 steps each. In the NVT and NPT equilibration stages, use the velocity Verlet integrator. Couple the temperature with V-rescale and the pressure with C-rescale. Each stage lasts for 2 ns. For the molecular dynamic simulation, set a time step of 2 fs for a total of 200 ns. Record trajectory frames every 10 ps to obtain 20,000 conformations. Maintain a constant temperature of 300 K. Apply a positional restraint of 1000 kJ/(mol·nm2) to the ligand. Analyze the structure using GROMACS commands to calculate Root mean square deviation (RMSD), Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of gyration (Rg), Solvent accessible surface area (SASA), and Hydrogen bonds (Hbond). Visualize the xvg data files with qtGrace0.2.6.

4.14. Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR was used to quantify PPIA expression. cDNA was synthesized from RNA using the SuperScript IV Reverse Transcription Kit. The cDNA was diluted to 1 ng/µL. All primer efficiencies were between 90 and 110%, ensuring reliable quantification. The primers were used as follows: PPIA (5′-AGCATACAGGTCCTGGCATCTTGT-3′, 5′-CAAAGACCACATGCTTGCCATCCA-3′), and GAPDH (5′-CGACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCC-3′, 5′-TGGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCCTT-3′). The PCR was performed on a C1000™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with these steps: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 30 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, the annealing temperature for 30 s, and a melting curve. Data were normalized to GAPDH using the ΔΔCt method.

4.15. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons were executed using GraphPad Prism. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM to reflect data variability. Intergroup differences were evaluated with a t-test, where p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.