Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A, and ABCG2 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Disposition in Chinese Healthy Subjects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Population

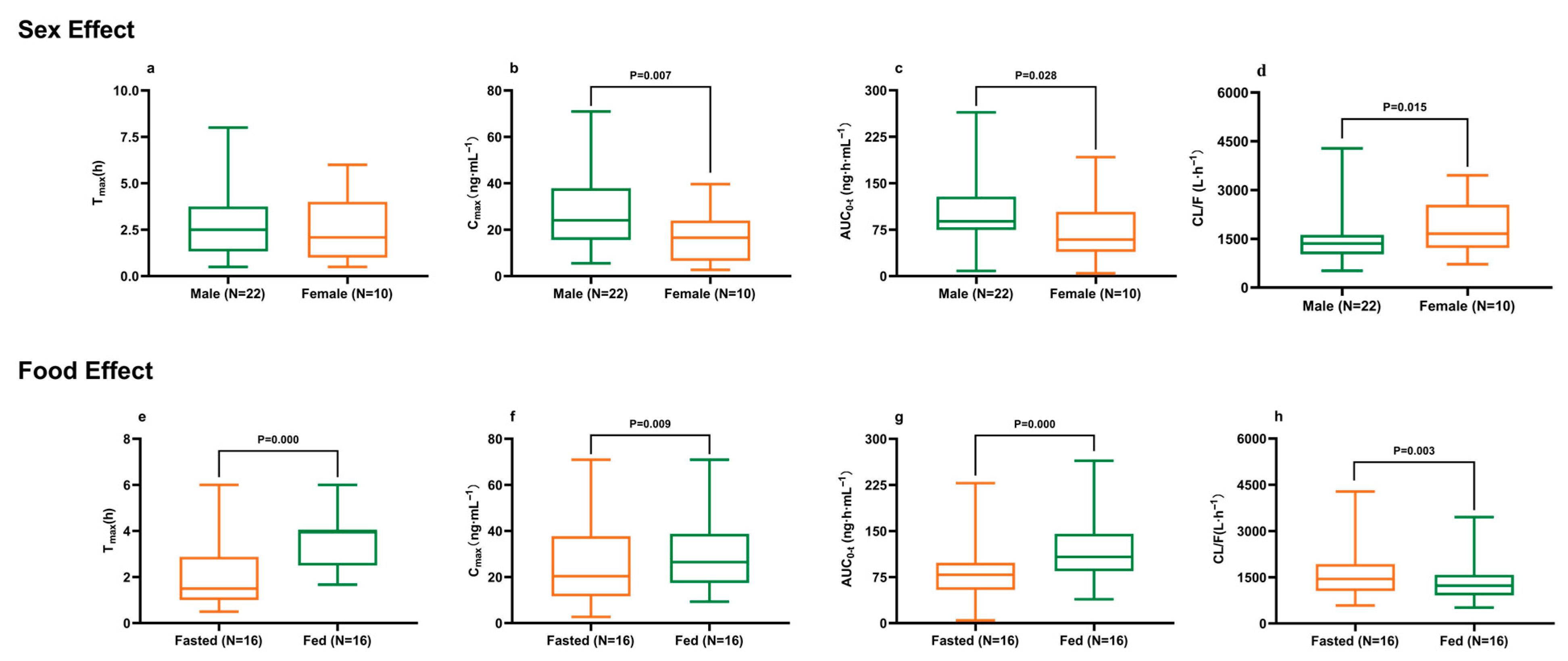

2.2. Demographics and Dietary Impact on Ibrutinib Pharmacokinetics

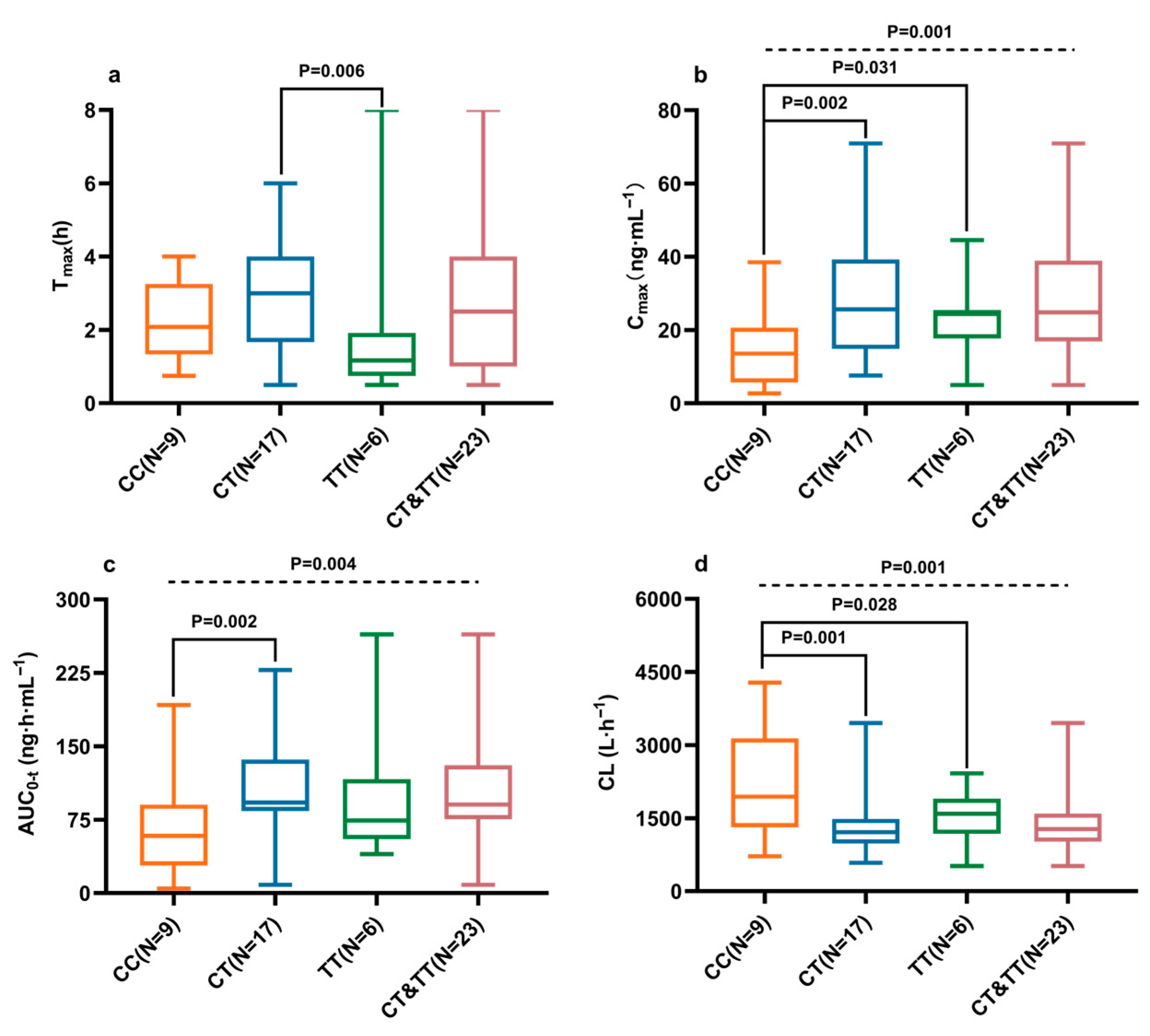

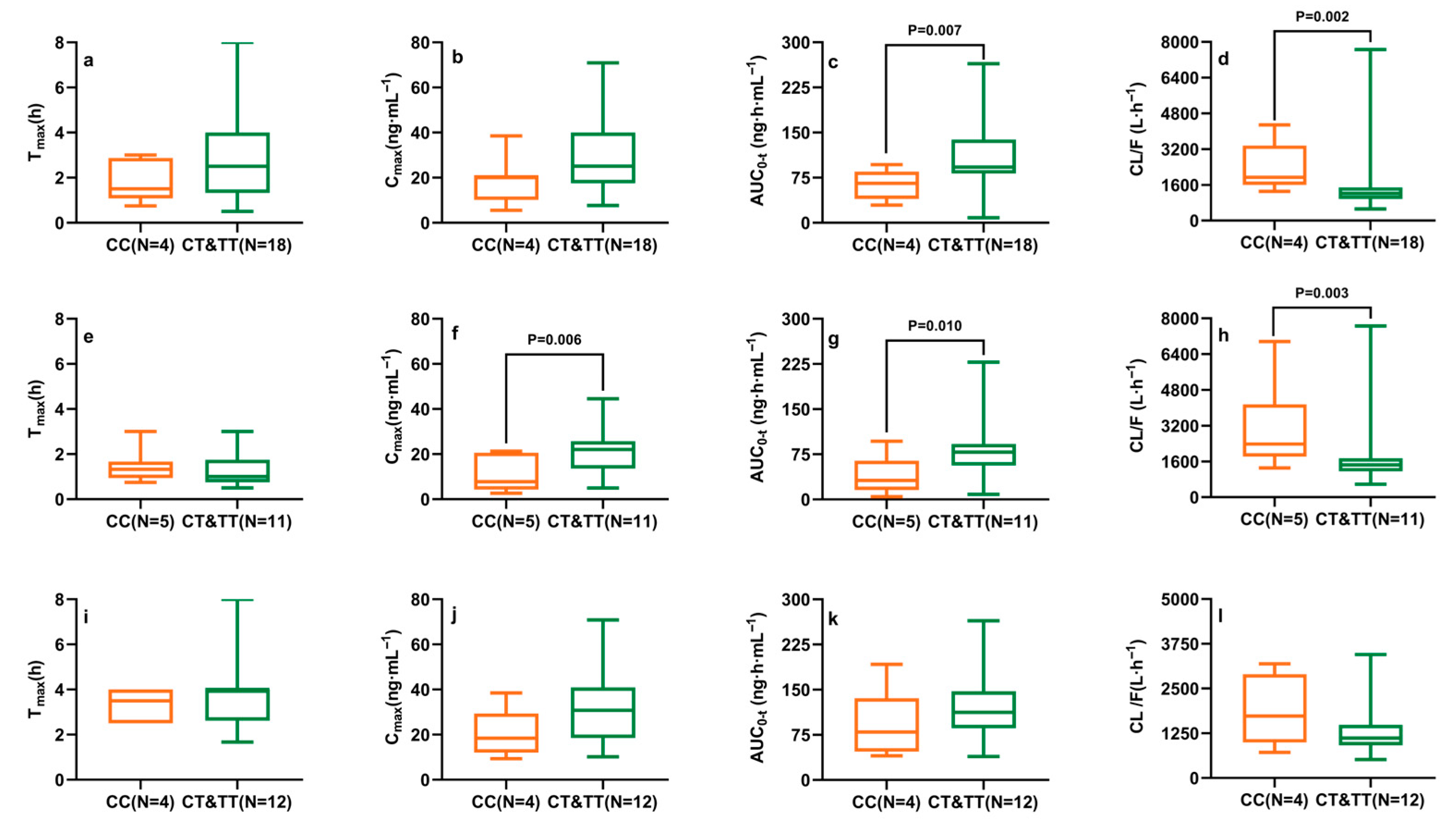

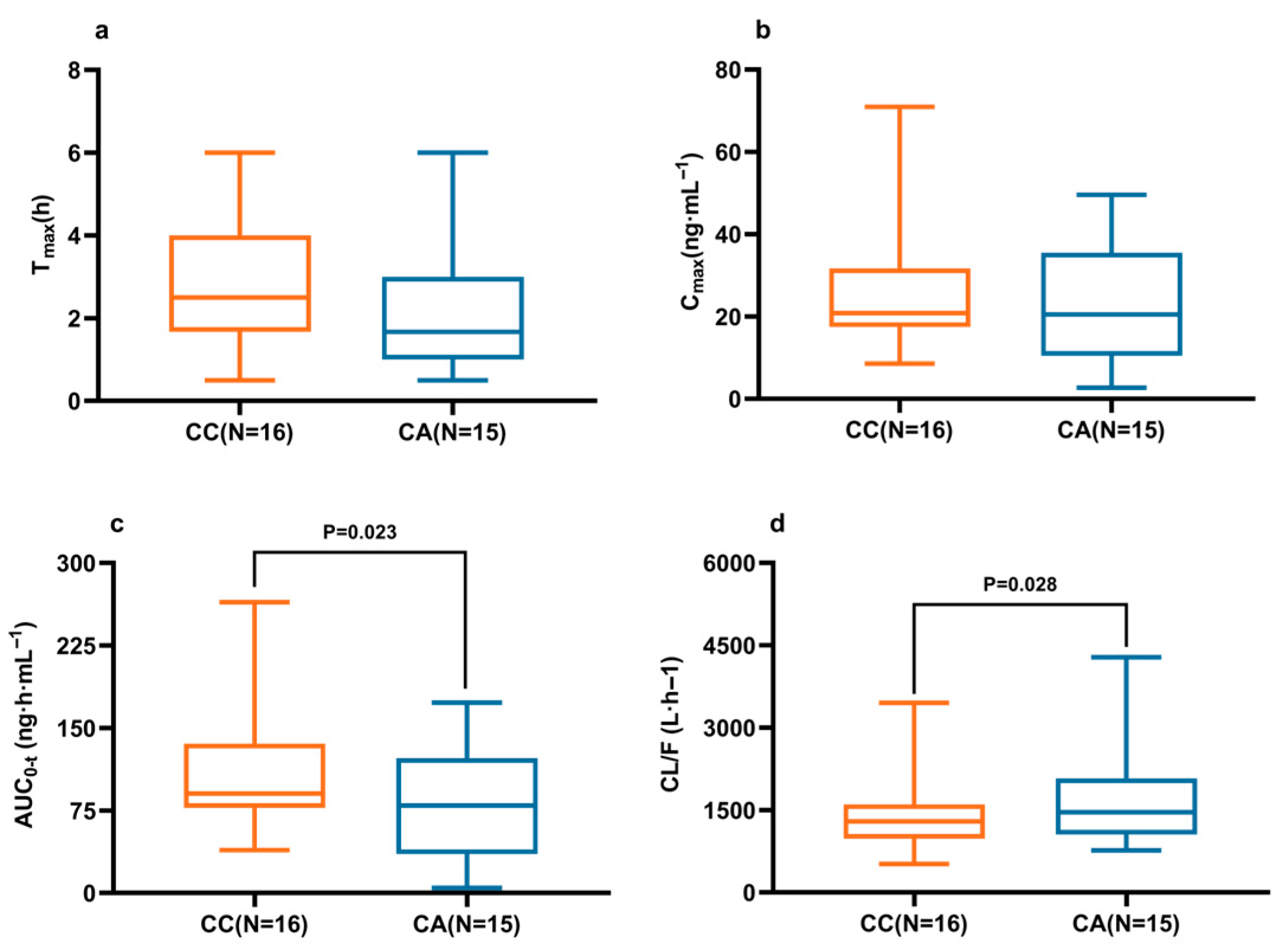

2.3. Effects of CYP2D6, CYP3A4/5, and ABCG2 Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Pharmacokinetics

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Determination of Ibrutinib in Human Plasma

4.3. Genotyping Analysis

4.4. Pharmacokinetic and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CL/F | Apparent clearance |

| Cmax | Maximum plasma concentration |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| Tmax | Time to maximum concentration |

| CLL | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| SLL | Small lymphocytic lymphoma |

| BTK | Bruton’s tyrosine kinase |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ALT | Serum alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Serum aspartate aminotransferase |

| CREA | Serum creatinine |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| MAF | Minor allele frequencies |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium |

References

- McDermott, J.; Jimeno, A. Ibrutinib for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma. Drugs Today 2014, 50, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wang, T.; Pan, L.; Xu, W.; Jin, J.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Hu, J.; Feng, R.; Li, P.; et al. Improved efficacy and safety of zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (R/R CLL) in China: A subgroup of ALPINE. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 4183–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-J.; Liu, X.; Pang, X.-J.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Yu, G.-X.; Li, Y.-R.; Guan, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Song, J.; Zhang, Q.-R.; et al. Progress in the development of small molecular inhibitors of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) as a promising cancer therapy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 47, 116358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolska-Washer, A.; Robak, T. Zanubrutinib for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies: Current status and future directions. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1130595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herishanu, Y.; Pérez-Galán, P.; Liu, D.; Biancotto, A.; Pittaluga, S.; Vire, B.; Gibellini, F.; Njuguna, N.; Lee, E.; Stennett, L.; et al. The lymph node microenvironment promotes B-cell receptor signaling, NF-kappaB activation, and tumor proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, M.F.M.; Kuil, A.; Geest, C.R.; Eldering, E.; Chang, B.Y.; Buggy, J.J.; Pals, S.T.; Spaargaren, M. The clinically active BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 targets B-cell receptor- and chemokine-controlled adhesion and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2012, 119, 2590–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Scheerens, H.; Li, S.; Schultz, B.E.; Sprengeler, P.A.; Burrill, L.C.; Mendonca, R.V.; Sweeney, M.D.; Scott, K.C.K.; Grothaus, P.G.; et al. Discovery of selective irreversible inhibitors for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Chem. Med. Chem. 2007, 2, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoppe, S.; Rood, J.J.M.; Buil, L.; Wagenaar, E.; Sparidans, R.W.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. P-Glycoprotein (MDR1/ABCB1) Restricts Brain Penetration of the Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib, While Cytochrome P450-3A (CYP3A) Limits Its Oral Bioavailability. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 5124–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharmacyclics LLC. Imbruvica (Ibrutinib) [Prescribing Information]; Pharmacyclics LLC: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/205552s043,210563s019,217003s004lbl.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Rood, J.J.M.; Jamalpoor, A.; van Hoppe, S.; van Haren, M.J.; Wasmann, R.E.; Janssen, M.J.; Schinkel, A.H.; Masereeuw, R.; Beijnen, J.H.; Sparidans, R.W. Extrahepatic metabolism of ibrutinib. Investig. New Drugs 2021, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yuan, J.-J.; Kan, Q.-C.; Zhang, L.-R.; Chang, Y.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-S. Influence of CYP3A5*3 polymorphism and interaction between CYP3A5*3 and CYP3A4*1G polymorphisms on post-operative fentanyl analgesia in Chinese patients undergoing gynaecological surgery. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 28, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Hernandez, S.; Aquilante, C.L.; Deininger, K.M.; Lindenfeld, J.; Schlendorf, K.H.; Van Driest, S.L. Composite CYP3A (CYP3A4 and CYP3A5) phenotypes and influence on tacrolimus dose adjusted concentrations in adult heart transplant recipients. Pharmacogenom. J. 2024, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Xiang, J.; Wang, N.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J. The impact of ABCB1, CYP3A4/5 and ABCG2 gene polymorphisms on rivaroxaban trough concentrations and bleeding events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Hum. Genom. 2023, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Yang, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Yan, Y.; Fu, K.; Jiang, W.; Xu, Y.; Wu, R.; et al. Effect of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on plasma concentration and therapeutic effect of risperidone. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rostami, G.; Hamid, M.; Shafiei, M.; Azizi, M.; Bahmani, H. Association of ABCB1, ABCG2 drug transporter polymorphisms and smoking with disease risk and cytogenetic response to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Leuk. Res. 2023, 126, 107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Ning, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; et al. Influences of ABC transporter and CYP3A4/5 genetic polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics of lenvatinib in Chinese healthy subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Ren, G.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; et al. ABCC2 c.-24 C>T single-nucleotide polymorphism was associated with the pharmacokinetic variability of deferasirox in Chinese subjects. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.; Skee, D.; Hellemans, P.; Jiao, J.; de Vries, R.; Swerts, D.; Lawitz, E.; Marbury, T.; Smith, W.; Sukbuntherng, J.; et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of ibrutinib in subjects with varying degrees of hepatic impairment. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marostica, E.; Sukbuntherng, J.; Loury, D.; de Jong, J.; de Trixhe, X.W.; Vermeulen, A.; De Nicolao, G.; O’bRien, S.; Byrd, J.C.; Advani, R.; et al. Population pharmacokinetic model of ibrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with B cell malignancies. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.; Sukbuntherng, J.; Skee, D.; Murphy, J.; O’bRien, S.; Byrd, J.C.; James, D.; Hellemans, P.; Loury, D.J.; Jiao, J.; et al. The effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of oral ibrutinib in healthy participants and patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chong, R.; Yang, S.; He, K.; Wen, Q. Bioequivalence of generic and branded ibrutinib capsules in healthy Chinese volunteers under fasting and fed conditions: A randomized, four-period, fully replicated, crossover study. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2025, 21, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrouri, B.; Yang, F.; Schwing, Q.; Dürig, T.; Fassihi, R. Hot-melt extrusion based sustained release ibrutinib delivery system: An inhibitor of Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK). Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 607, 120981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Product Quality Review: NDA 210563Orig1s000–210563Orig2s000. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2018/210563Orig1s000,210563Orig2s000ChemR.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2017).

- Hu, K.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Sheng, X.; Li, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ye, X.; Cui, Y. Effects of Vitamin D Receptor, Cytochrome P450 3A, and Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase Genetic Polymorphisms on the Pharmacokinetics of Remimazolam in Healthy Chinese Volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2021, 10, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratte, C.D.; Polesel, J.; Gagno, S.; Posocco, B.; De Mattia, E.; Roncato, R.; Orleni, M.; Puglisi, F.; Guardascione, M.; Buonadonna, A.; et al. Impact of ABCG2 and ABCB1 Polymorphisms on Imatinib Plasmatic Exposure: An Original Work and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Gómez, N.; Sanz-Solas, A.; Cuevas, B.; Cuevas, M.V.; Alonso-Madrigal, C.; Loscertales, J.; Álvarez-Nuño, R.; García, C.; Zubiaur, P.; Villapalos-García, G.; et al. Pharmacogenetic Biomarkers of Ibrutinib Response and Toxicity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Insights from an Observational Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Wen, J.; Tang, P.; Wang, C.; Xie, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Hu, G. Functional Characterization of 22 CYP3A4 Protein Variants to Metabolize Ibrutinib In Vitro. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 122, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean (95% Confidence Interval) | Median (Quartile) |

|---|---|---|

| Male, N (%) | 22 (68.8) | |

| Age (years) | 33 (31, 35) | 32 (29, 35) |

| Body Weight (kg) | 69.2 (66.6, 71.8) | 70.5 (62.4, 74.4) |

| Height (cm) | 169.8 (167.3, 172.2) | 170.3 (166.0, 173.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (23.4, 24.5) | 24.4 (22.9, 25.3) |

| ALT (U/L) | 28 (23, 32) | 26 (16, 43) |

| AST (U/L) | 25 (22, 28) | 23 (19, 29) |

| CREA (μmol/L) | 70.5 (65.2, 75.8) | 71.4 (61.2, 82.7) |

| SNP | rs ID | Genotypic Frequency N (%) | Mutant Allele | MAF 2 | HWE 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild | Hetero | Variant | Study | East Asian 1 | American 1 | Europe 1 | ||||

| CYP2D6 c.100C>T | rs1065852 | CC, 9 (28.1) | CT, 17 (53.1) | TT, 6 (18.8) | T | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.919 |

| CYP2D6 c.2851 C>T | rs16947 | CC, 17 (53.1) | CT, 13 (40.6) | TT, 2 (6.3) | T | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.974 |

| CYP3A4 c.22545G>A | rs2242480 | GG, 18 (56.2) | GA, 12 (37.5) | AA, 2 (6.3) | A | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 1.000 |

| CYP3A5 c.6986 G>A | rs776746 | GG, 20 (62.5) | GA, 11 (34.4) | AA, 1 (3.1) | A | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.938 |

| ABCG2 c.34 G>A | rs2231137 | GG, 12 (37.5) | GA, 13 (40.6) | AA, 7 (21.9) | A | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.632 |

| ABCG2 c.421 C>A | rs2231142 | CC, 16 (50.0) | CA, 15 (46.88) | AA, 1 (3.13) | A | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.532 |

| Sex | Male (N = 22) | Female (N = 10) | p 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax (h) | 2.50 (1.33, 3.75) | 2.09 (1.00, 4.00) | 0.635 |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 24.07 (15.60, 37.88) | 16.58 (6.60, 23.92) | 0.007 ** |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 88.54 (74.56, 128.34) | 58.91 (39.15, 103.80) | 0.028 * |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1413 (1031, 1702) | 2021 (1242, 3177) | 0.015 * |

| Food | Fasted (N = 16) | Fed (N = 16) | p 1 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.33 (0.75, 1.67) | 4.00 (2.50, 4.00) | 0.000 *** |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 18.68 (8.68, 24.88) | 26.51 (17.44, 38.77) | 0.009 ** |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 73.56 (35.45, 88.52) | 107.73 (84.76, 145.50) | 0.000 *** |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1692 (1313, 2615) | 1225 (913, 1581) | 0.003 ** |

| CYP2D6 c.100C>T | CC (N = 9) | CT (N = 17) | TT (N = 6) | CT&TT (N = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax (h) | 2.09 (1.33, 3.25) | 3.00 (1.67, 4.00) | 1.17 (0.75, 1.92) | 2.50 (1.00, 4.00) |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 13.59 (5.71, 20.61) | 25.66 (14.88, 39.27) | 24.4 (17.73, 25.48) | 24.84 (16.89, 38.93) |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 58.54 (28.21, 90.50) | 92.49 (83.83, 136.53) | 74.15 (55.13, 116.32) | 90.47 (75.45, 130.79) |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 2124 (1481, 3910) | 1222 (1003, 1560) | 1591 (1178, 1900) | 1356 (1021, 1618) |

| CYP2D6 c.2851 C>T | CC (N = 17) | CT (N = 13) | TT (N = 2) | p |

| Tmax (h) | 1.67 (1.00, 3.25) | 3.00 (1.33, 4.00) | 2.50 (2.50, 2.88) | 0.400 |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 22.53 (16.89, 32.87) | 18.43 (10.47, 34.81) | 26 (16.68, 37.00) | 0.445 |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 86.12 (60.90, 115.65) | 84.48 (38.53, 131.77) | 79.46 (63.92, 131.59) | 0.744 |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1468 (1133, 1729) | 1293 (1003, 3152) | 1731 (1059, 2113) | 0.889 |

| CYP3A4 c.22545 G>A | GG (N = 18) | GA (N = 12) | AA (N = 2) | p 1 |

| Tmax (h) | 4.25 (1.19, 6.00) | 3.00 (1.75, 4.00) | 1.67 (1.00, 3.75) | 0.077 |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 18.92 (12.81, 39.40) | 22.03 (15.57, 35.64) | 20.40 (10.38, 28.48) | 0.531 |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 78.72 (51.74, 114.23) | 92.27 (81.83, 133.09) | 74.89 (39.19, 107.13) | 0.075 |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1663 (1208, 2693) | 1249 (1016, 1524) | 1653 (1110, 3177) | 0.033 * |

| CYP3A5 c.6986 G>A | GG (N = 20) | GA (N = 11) | AA (N = 1) | p 2 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.67 (1.00, 4.00) | 2.50 (1.59, 3.25) | -- | 0.038 * |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 20.40 (11.00, 31.58) | 24.07 (16.80, 36.64) | 13.15 | 0.251 |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 82.92 (40.62, 121.79) | 92.27 (75.70, 129.08) | 64.67 | 0.134 |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1559 (1078, 3024) | 1249 (990, 1618) | 2273.82 | 0.066 |

| ABCG2 c.34G>A | GG (N = 12) | GA (N = 13) | AA (N = 7) | p |

| Tmax (h) | 1.84 (1.08, 3.00) | 2.50 (1.00, 4.00) | 2.75 (1.92, 4.00) | 0.278 |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 19.26 (9.43, 35.36) | 21.18 (16.61, 32.87) | 24.4 (13.54, 36.09) | 0.502 |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 83.9 (60.80, 103.8) | 85.48 (54.43, 112.27) | 98.18 (56.02, 152.79) | 0.676 |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1531 (1091, 1936) | 1452 (1104, 2159) | 1347 (867, 2302) | 0.744 |

| ABCG2 c.421C>A | CC (N = 16) | CA (N = 15) | AA (N = 1) | p 3 |

| Tmax (h) | 2.50 (1.67, 4.00) | 1.67 (1.00, 3.00) | 1.34 | 0.158 |

| Cmax (ng·mL−1) | 20.81 (17.44, 31.71) | 20.48 (10.47, 35.49) | 7.04 | 0.095 |

| AUC0-t (ng·h·mL−1) | 90.47 (77.28, 135.64) | 74.89 (32.78, 116.06) | 50.33 | 0.023 * |

| CL/F (L·h−1) | 1293 (980, 1602) | 1631 (1129, 3339) | 1879 | 0.028 * |

| SNP (rs ID) | Primer Name | Primer Sequence | Sequencing Sequence | Sequencing Primer | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 c.100C>T | CYP2D6-rs1065852-F | TGCCATGTATA AATGCCCTTCT | CYP2D6-rs1065852-RS | TGAGGCAGGT ATGGGGCTAG | 355 |

| (rs1065852) | CYP2D6-rs1065852-R | TTGGTAGTGAG GCAGGTATGG | |||

| CYP2D6 c.2851 C>T | CYP2D6-rs16947-F | CGGGTGTCCC AGCAAAGTT | CYP2D6-rs16947-FS | CCTCGGCCCC TGCACTGTT | 264 |

| (rs16947) | CYP2D6-rs16947-R | CTACCCCGTT CTGTCCCGA | |||

| CYP3A4 c.22545G>A | CYP3A4-1G-F | AGAGCCTTCCTA CATAGAGTCAG | CYP3A4-1G-S | GCAGTGTTCTCT CCTTCATTATG | 394 |

| (rs2242480) | CYP3A4-1G-R | CCTTAGGGAT TTGAGGGCTT | |||

| CYP3A5 c.6986A>G | CYP3A5-2-F | TAGTAGACAGA TGACACAGCTC | CYP3A5-S | GAGAGTGGCAT AGGAGATACC | 569 |

| (rs776746) | CYP3A5-2-R | TCACTAGCACT GTTCTGATCAC | |||

| ABCG2 c.34G>A | rs2231137-F | TGCCTGTCTTC CCATTTAGGTT | rs2231137-F | TGCCTGTCTTC CCATTTAGGTT | 474 |

| (rs2231137) | rs2231137-R | AGCCAAAACCTG TGAGGTTCACTG | |||

| ABCG2 c.421G>T | rs2231142-F | AAACAGTCATGGT CTTAGAAAAGAC | rs2231142-F | AAACAGTCATGGT CTTAGAAAAGAC | 197 |

| (rs2231142) | rs2231142-R | AGACCTAACTCT TGAATGACCCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, K.; Wang, Y.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Qian, J.; Chen, X.; Liang, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhao, D. Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A, and ABCG2 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Disposition in Chinese Healthy Subjects. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111615

Fu K, Wang Y, Duan L, Zhang Z, Qian J, Chen X, Liang Y, Lu C, Zhao D. Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A, and ABCG2 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Disposition in Chinese Healthy Subjects. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111615

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Kejia, Yao Wang, Lingyan Duan, Zhenyuan Zhang, Jialing Qian, Xijing Chen, Yi Liang, Chengcan Lu, and Di Zhao. 2025. "Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A, and ABCG2 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Disposition in Chinese Healthy Subjects" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111615

APA StyleFu, K., Wang, Y., Duan, L., Zhang, Z., Qian, J., Chen, X., Liang, Y., Lu, C., & Zhao, D. (2025). Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A, and ABCG2 Genetic Polymorphisms on Ibrutinib Disposition in Chinese Healthy Subjects. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111615