Efficacy of Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Acute and Maintenance Randomised Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility Criteria, Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.3. Meta-Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bipolar Disorder

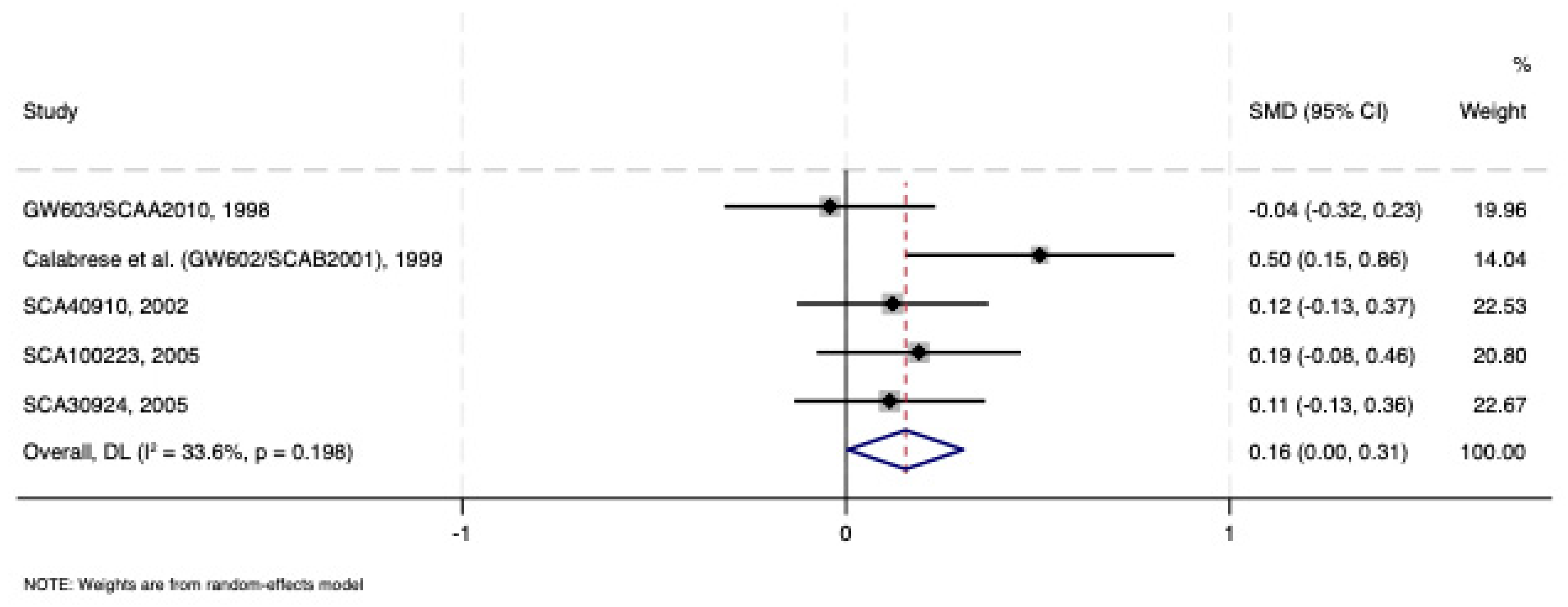

3.1.1. Acute Lamotrigine Monotherapy Treatment vs. Placebo

3.1.2. Acute Lamotrigine vs. Placebo as Adjunctive Treatment

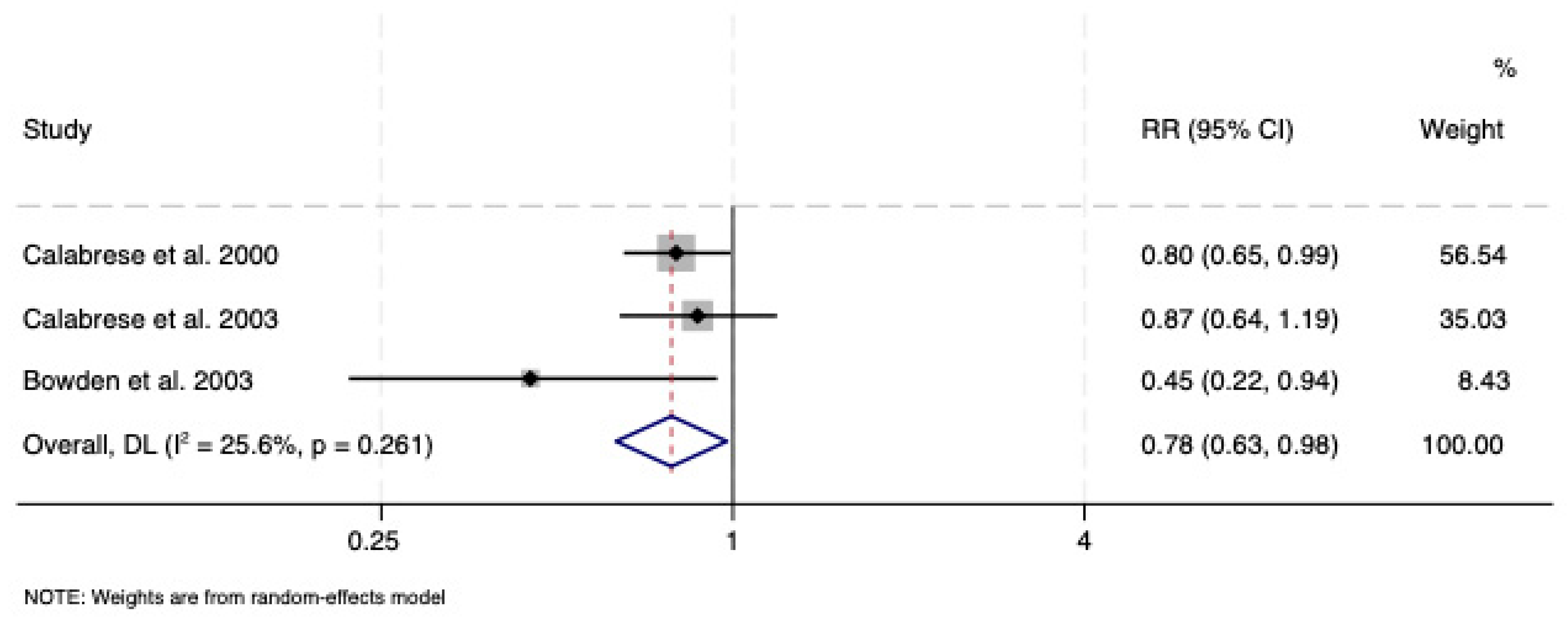

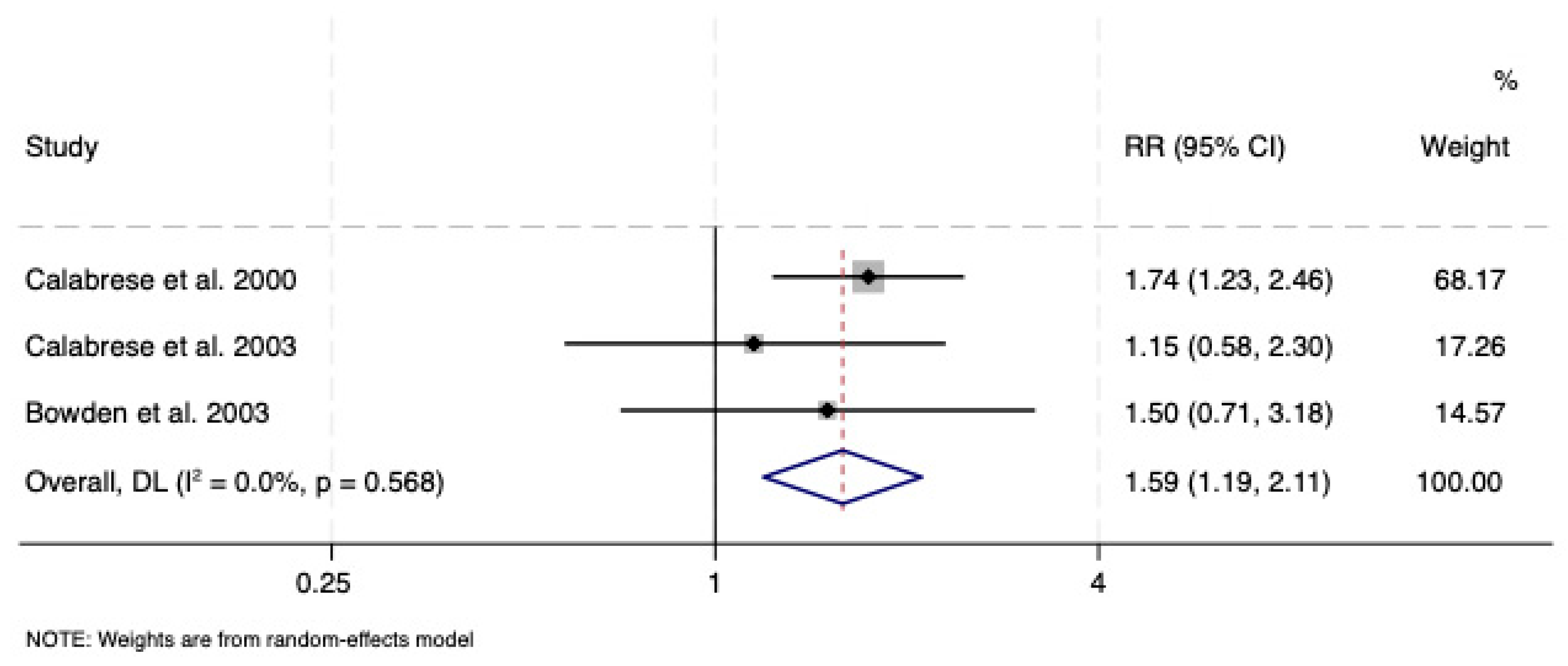

3.2. Maintenance Treatment

3.2.1. Lamotrigine vs. Placebo

3.2.2. Lamotrigine vs. Lithium

3.2.3. Lamotrigine vs. Olanzapine/Fluoxetine Combination

3.3. Unipolar Depression

3.3.1. Acute Monotherapy Treatment

3.3.2. Acute Adjunctive Treatment

3.3.3. Acute Comparison with an Active Compound

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, B.; Vale, N. Understanding Lamotrigine’s Role in the CNS and Possible Future Evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 3878, Lamotrigine. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lamotrigine (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- European Medicine Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/lamictal (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Yildiz, A.; Siafis, S.; Mavridis, D.; Vieta, E.; Leucht, S. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological interventions for acute bipolar depression in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, A.; Pariante, C.M.; Young, A.H.; Anderson, I.M.; Christmas, D.; Cowen, P.J.; Dickens, C.; Ferrier, I.N.; Geddes, J.; Gilbody, S.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: A revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 29, 459–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.W.; Kennedy, S.H.; Adams, C.; Bahji, A.; Beaulieu, S.; Bhat, V.; Blier, P.; Blumberger, D.M.; Brietzke, E.; Chakrabarty, T.; et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023: Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2024, 69, 641–687. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, J.R.; Calabrese, J.R.; Goodwin, G.M. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: Independent meta-analysis and meta-regression of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenen, N.; Kamperman, A.M.; Prodan, A.; Nolen, W.A.; Boks, M.P.; Wesseloo, R. The efficacy of lamotrigine in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2024, 26, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Zaninotto, L.; van der Loos, M.L.; Gao, K.; Schaffer, A.; Reis, C.; Normann, C.; Anghelescu, I.G.; Correll, C.U.; et al. Lamotrigine compared to placebo and other agents with antidepressant activity in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression: A comprehensive meta-analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes in short-term trials. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, K.K.; Chen, C.-H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Lu, M.-L. Lamotrigine augmentation in treatment-resistant unipolar depression: A comprehensive meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Cochrane Collaboration. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, S.; Adams, R.; Walsh, C. The use of continuous data versus binary data in MTC models: A case study in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royston, P.; Altman, D.G.; Sauerbrei, W. Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: A bad idea. Stat. Med. 2006, 25, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnone, D.; Ramaraj, R.; Östlundh, L.; Arora, T.; Javaid, S.; Govender, R.D.; Stip, E.; Young, A.H. Assessment of cognitive domains in major depressive disorders using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): Systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 138, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnone, D.; McIntosh, A.M.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Munafò, M.R.; Anderson, I.M. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: Systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Cavanagh, J.; Gerber, D.; Lawrie, S.M.; Ebmeier, K.P.; McIntosh, A.M. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Karmegam, S.R.; Östlundh, L.; Alkhyeli, F.; Alhammadi, L.; Alhammadi, S.; Alkhoori, A.; Selvaraj, S. Risk of suicidal behavior in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder—A systematic review and meta-analysis of registry-based studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 159, 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Omar, O.; Arora, T.; Östlundh, L.; Ramaraj, R.; Javaid, S.; Govender, R.D.; Ali, B.R.; Patrinos, G.P.; Young, A.H.; et al. Effectiveness of pharmacogenomic tests including CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genomic variants for guiding the treatment of depressive disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 144, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H. Difference in Means Calculation. Available online: https://stattrek.com/sampling/difference-in-means (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook. Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook/current (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials. 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridis, D.; White, I.R. Dealing with missing outcome data in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 2020, 11, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, J.R.; Bowden, C.L.; Sachs, G.S.; Ascher, J.A.; Monaghan, E.; Rudd, G.D. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSK SR. GW603/SCAA2010. 1998. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCAA2010 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- GSK SR. SCA40910. 2002. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCA40910 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- GSK SR. SCA100223. 2005. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCA100223 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- GSK SR. SCA30924. 2005. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCA30924 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Suppes, T.; Marangell, L.B.; Bernstein, I.H.; Kelly, D.I.; Fischer, E.G.; Zboyan, H.A.; Snow, D.E.; Martinez, M.; Al Jurdi, R.; Shivakumar, G.; et al. A single blind comparison of lithium and lamotrigine for the treatment of bipolar II depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 111, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Dunner, D.L.; McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E.; Adams, D.H.; Degenhardt, E.; Tohen, M.; Houston, J.P. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination vs. lamotrigine in the 6-month treatment of bipolar I depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 12, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Loos, M.L.; Mulder, P.G.; Hartong, E.G.; Blom, M.B.; Vergouwen, A.C.; de Keyzer, H.J.; Notten, P.J.; Luteijn, M.L.; Timmermans, M.A.; Vieta, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of lamotrigine as add-on treatment to lithium in bipolar depression: A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.E.; Gao, K.; Fein, E.B.; Chan, P.K.; Conroy, C.; Obral, S.; Ganocy, S.J.; Calabrese, J.R. Lamotrigine as add-on treatment to lithium and divalproex: Lessons learned from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012, 14, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes, J.R.; Gardiner, A.; Rendell, J.; Voysey, M.; Tunbridge, E.; Hinds, C.; Yu, L.M.; Hainsworth, J.; Attenburrow, M.J.; Simon, J.; et al. Comparative evaluation of quetiapine plus lamotrigine combination versus quetiapine monotherapy (and folic acid versus placebo) in bipolar depression (CEQUEL): A 2 × 2 factorial randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, J.R.; Suppes, T.; Bowden, C.L.; Sachs, G.S.; Swann, A.C.; McElroy, S.L.; Kusumakar, V.; Ascher, J.A.; Earl, N.L.; Greene, P.L.; et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Lamictal 614 Study Group. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, J.R.; Bowden, C.L.; Sachs, G.; Yatham, L.N.; Behnke, K.; Mehtonen, O.P.; Montgomery, P.; Ascher, J.; Paska, W.; Earl, N.; et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, C.L.; Calabrese, J.R.; Sachs, G.; Yatham, L.N.; Asghar, S.A.; Hompland, M.; Montgomery, P.; Earl, N.; Smoot, T.M.; DeVeaugh-Geiss, J.; et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licht, R.W.; Nielsen, J.N.; Gram, L.F.; Vestergaard, P.; Bendz, H. Lamotrigine versus lithium as maintenance treatment in bipolar I disorder: An open, randomized effectiveness study mimicking clinical practice. The 6th trial of the Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG-6). Bipolar Disord. 2010, 12, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSK SR. SCAA2011. 1998. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCAA2011 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- GSK SR. SCA20022. 1999. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCA20022 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- GSK SR. SCA20025. 2000. Available online: https://www.gsk-studyregister.com/en/trial-details/?id=SCA20025 (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Santos, M.A.; Rocha, F.L.; Hara, C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine in patients with treatment-resistant depression: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 10, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.; Berk, M.; Vorster, M. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation with lamotrigine or placebo in patients concomitantly treated with fluoxetine for resistant major depressive episodes. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, C.; Hummel, B.; Schärer, L.O.; Hörn, M.; Grunze, H.; Walden, J. Lamotrigine as adjunct to paroxetine in acute depression: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2002, 63, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbee, J.G.; Thompson, T.R.; Jamhour, N.J.; Stewart, J.W.; Conrad, E.J.; Reimherr, F.W.; Thompson, P.M.; Shelton, R.C. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of lamotrigine as an antidepressant augmentation agent in treatment-refractory unipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, F.; Anghelescu, I.G. Lithium versus lamotrigine augmentation in treatment resistant unipolar depression: A randomized, open-label study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 22, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, G.; Ricciardi, T.; Tavella, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. A Single-Blind Randomized Comparison of Lithium and Lamotrigine as Maintenance Treatments for Managing Bipolar II Disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrocea, G.V.; Dunn, R.M.; Frye, M.A.; Ketter, T.A.; Luckenbaugh, D.A.; Leverich, G.S.; Speer, A.M.; Osuch, E.A.; Jajodia, K.; Post, R.M. Clinical predictors of response to lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory affective disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.B.; McElroy, S.L.; Keck, P.E.; Deldar, A.; Adams, D.H.; Tohen, M.; Williamson, D.J. A 7-week, randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination versus lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar I depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Arnold, J.G.; Prihoda, T.J.; Quinones, M.; Singh, V.; Schinagle, M.; Conroy, C.; D’Arcangelo, N.; Bai, Y.; Calabrese, J.R.; et al. Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Treatment (SMART) for Bipolar Disorder at Any Phase of Illness and at least Mild Symptom Severity. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2020, 50, 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg, A.A.; Ostacher, M.J.; Calabrese, J.R.; Ketter, T.A.; Marangell, L.B.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Miyahara, S.; Bauer, M.S.; Thase, M.E.; Wisniewski, S.R.; et al. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: A STEP-BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, A.; Zuker, P.; Levitt, A. Randomized, double-blind pilot trial comparing lamotrigine versus citalopram for the treatment of bipolar depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 96, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, W.A.; Kupka, R.W.; Hellemann, G.; Frye, M.A.; Altshuler, L.L.; Leverich, G.S.; Suppes, T.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; McElroy, S.; Grunze, H.; et al. Tranylcypromine vs. lamotrigine in the treatment of refractory bipolar depression: A failed but clinically useful study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007, 115, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Loos, M.L.; Mulder, P.; Hartong, E.G.; Blom, M.B.; Vergouwen, A.C.; van Noorden, M.S.; Timmermans, M.A.; Vieta, E.; Nolen, W.A.; LamLit Study Group. Efficacy and safety of two treatment algorithms in bipolar depression consisting of a combination of lithium, lamotrigine or placebo and paroxetine. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 122, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, K.; Kemp, D.E.; Chan, P.K.; Serrano, M.B.; Conroy, C.; Fang, Y.; Ganocy, S.J.; Findling, R.L.; Calabrese, J.R. Lamotrigine adjunctive therapy to lithium and divalproex in depressed patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder and a recent substance use disorder: A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2010, 43, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- van der Loos, M.L.; Mulder, P.; Hartong, E.G.; Blom, M.B.; Vergouwen, A.C.; van Noorden, M.S.; Timmermans, M.A.; Vieta, E.; Nolen, W.A.; LamLit Study Group. Long-term outcome of bipolar depressed patients receiving lamotrigine as add-on to lithium with the possibility of the addition of paroxetine in nonresponders: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a novel design. Bipolar Disord. 2011, 13, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, C.L.; Singh, V.; Weisler, R.; Thompson, P.; Chang, X.; Quinones, M.; Mintz, J. Lamotrigine vs. lamotrigine plus divalproex in randomized, placebo-controlled maintenance treatment for bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012, 126, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Mean Difference, Standardized Mean Difference (SMD), and Their Use in Meta-Analysis: As Simple as It Gets. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joober, R.; Schmitz, N.; Annable, L.; Boksa, P. Publication bias: What are the challenges and can they be overcome? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012, 37, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golder, S.; Loke, Y.K.; Bland, M. Unpublished data can be of value in systematic reviews of adverse effects: Methodological overview. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stip, E.; Rizvi, T.A.; Mustafa, F.; Javaid, S.; Aburuz, S.; Ahmed, N.N.; Abdel Aziz, K.; Arnone, D.; Subbarayan, A.; Al Mugaddam, F.; et al. The Large Action of Chlorpromazine: Translational and Transdisciplinary Considerations in the Face of COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 577678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, S.; Walker, C.; Arnone, D.; Cao, B.; Faulkner, P.; Cowen, P.J.; Roiser, J.P.; Howes, O. Effect of Citalopram on Emotion Processing in Humans: A Combined 5-HT1A [11C]CUMI-101 PET and Functional MRI Study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Bipolar Type | Comparator | Lamotrigine Target Dose | Lamotrigine N. | Comparator N. | Mean Age | Women (Cases) N. | Duration Weeks | Rating Scale | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar depression: Acute phase monotherapy | ||||||||||

| Calabrese et al. (GW602/SCAB2001), 1999 [28] | I | Placebo | 200 | 63 | 66 | 42 | 35 | 7 | HDRS17/MÅDRS/CGI-S | Low |

| GW603/SCAA2010, 1998 [29] | I/II | Placebo | 400 | 103 | 101 | 40.5 | 66 | 10 | HDRS17/MÅDRS/CGI-S | Low |

| SCA40910, 2002 [30] | I | Placebo | 200 | 129 | 118 | 37.6 | 74 | 8 | HDRS17/MÅDRS/CGI-S | Low |

| SCA100223, 2005 [31] | II | Placebo | 200 | 109 | 109 | 38.1 | 70 | 8 | HDRS17/MÅDRS/CGI-S | Low |

| SCA30924, 2005 [32] | I | Placebo | 200 | 127 | 122 | 40.5 | 69 | 8 | HDRS17/MÅDRS/CGI-S | Low |

| Suppes et al., 2008 [33] | II | Lithium | 400 | 41 | 49 | 36.9 | 30 | 16 | HDRS17 | Medium |

| Brown et al., 2009 [34] | I | Olanzapine + Fluoxetine | 200 | 205 | 205 | 36.8 | 128 | 25 | MÅDRS | Medium |

| 777 | 770 | 38.9 | 472 | 11.7 | ||||||

| Bipolar depression: Acute phase add-on | Weeks | |||||||||

| van Der Loos et al., 2009 [35] | I/II | Lithium + Placebo | 200 | 64 | 60 | 45.2 | 37 | 8 | MÅDRS | Low |

| Kemp et al., 2012 [36] | I/II | Lithium/Divalproate + Placebo | 200 | 23 | 26 | 35.7 | 12 | 12 | MÅDRS | Low |

| Geddes et al., 2016 [37] | I/II | Quetiapine + Placebo | 300 | 101 | 101 | 57 | 12 | QIDS SR 16 | Medium | |

| 188 | 187 | 40.45 | 106 | 10.6 | ||||||

| Bipolar depression: Maintenance phase | Months | |||||||||

| Calabrese et al. 2000 [38] | I/II | Placebo | 500 | 92 | 88 | 38.5 | 55 | 6 | HAM-D-17 | Low |

| Calabrese et al., 2003 [39] | I | Placebo | 500 | 215 | 119 | 44.1 | 99 | 18 | HAM-D-17 | Low |

| Calabrese et al., 2003 [39] | I | Lithium | 500 | NA | 120 | NA | NA | 18 | HAM-D-17 | |

| Bowden et al., 2003 [40] | I | Placebo | 400 | 58 | 69 | 40.6 | 32 | 18 | HAM-D-17 | Low |

| Bowden et al., 2003 [40] | I | Lithium | 400 | NA | 44 | NA | NA | 18 | HAM-D-17 | |

| Brown et al., 2009 [34] | I | Olanzapine + Fluoxetine | 200 | 205 | 205 | 36.8 | 128 | 25 | MÅDRS | Medium |

| Licht et al., 2010 [41] | I | Lithium | 400 | 77 | 78 | 38.2 | 40 | 69.59 | MES | Medium |

| 647 | 723 | 39.64 | 354 | 24.6 | ||||||

| Unipolar depression: Acute phase monotherapy | Weeks | |||||||||

| SCAA2011, 1998 [42] | NA | Placebo | 200 | 152 | 150 | 39 | 99 | 8 | HAM-D 17/MÅDRS/CGI-I | Low |

| SCA20022, 1999 [43] | NA | Placebo | 200 | 75 | 77 | 41.9 | 32 | 7 | HAM-D 17/MÅDRS/CGI-I | Low |

| SCA20025, 2000 [44] | NA | Placebo | 200 | 151 | 150 | 41.1 | 40 | 7 | HAM-D 17/MÅDRS/CGI-I | Low |

| Santos et al., 2008 [45] | NA | Placebo | 200 | 17 | 17 | 38.2 | 171 | 8 | MÅDRS | Low |

| 395 | 394 | 40.05 | 342 | 7.5 | ||||||

| Unipolar depression: Acute phase add-on | ||||||||||

| Barbosa et al., 2003 [46] | NA | Fluoxetine + Placebo | 100 | 13 | 10 | 30.2 | 5 | 6 | HAM-D-17 | Medium |

| Normann et al., 2002 [47] | NA | Paroxetine + Placebo | 200 | 20 | 20 | 39.6 | 14 | 9 | HAM-D-21 | Medium |

| Barbee et al., 2011 [48] | NA | Paroxetine + Placebo | 400 | 48 | 48 | 44.59 | 33 | 10 | HAM-D 17/MÅDRS | Low |

| 81 | 78 | 38.13 | 52 | 8.3 | ||||||

| Unipolar depression: Direct comparison | Weeks | |||||||||

| SCAA2011, 1998 [42] | NA | Desipramine | 200 | 152 | 151 | 39 | 86 | 8 | HAM-D 17/MÅDRS/CGI-I | Low |

| Schindler and Anghelescu, 2007 [49] | NA | Lithium | 250 | 17 | 17 | 41.1 | 9 | 8 | HAM-D 17 | High |

| 169 | 168 | 40.05 | 95 | 8 |

| Bipolar Depression | Unipolar Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute phase in monotherapy | Evidence of superior efficacy of lamotrigine vs. placebo but not vs. lithium or vs. olanzapine/fluoxetine combination | No superior efficacy of lamotrigine vs. placebo or vs. desipramine |

| Acute phase as add-on treatment | No superior efficacy of lamotrigine when added to lithium or valproate compared to placebo | No superior efficacy of lamotrigine when added to fluoxetine or paroxetine |

| Maintenance phase | Evidence of superior efficacy of lamotrigine vs. placebo but not vs. lithium or vs. olanzapine/fluoxetine combination | No available studies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnone, D.; Östlundh, L.; Mosa, M.; MacDonald, B.; Oldershaw, J.; Qassem, T.; Young, A.H. Efficacy of Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Acute and Maintenance Randomised Controlled Trials. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101590

Arnone D, Östlundh L, Mosa M, MacDonald B, Oldershaw J, Qassem T, Young AH. Efficacy of Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Acute and Maintenance Randomised Controlled Trials. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(10):1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101590

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnone, Danilo, Linda Östlundh, Meena Mosa, Brianne MacDonald, Jonathan Oldershaw, Tarik Qassem, and Allan H. Young. 2025. "Efficacy of Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Acute and Maintenance Randomised Controlled Trials" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 10: 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101590

APA StyleArnone, D., Östlundh, L., Mosa, M., MacDonald, B., Oldershaw, J., Qassem, T., & Young, A. H. (2025). Efficacy of Lamotrigine in the Treatment of Unipolar and Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Acute and Maintenance Randomised Controlled Trials. Pharmaceuticals, 18(10), 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101590