Involvement of the Expression of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Schizophrenia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Items

3. Results

3.1. The Final Studies Included

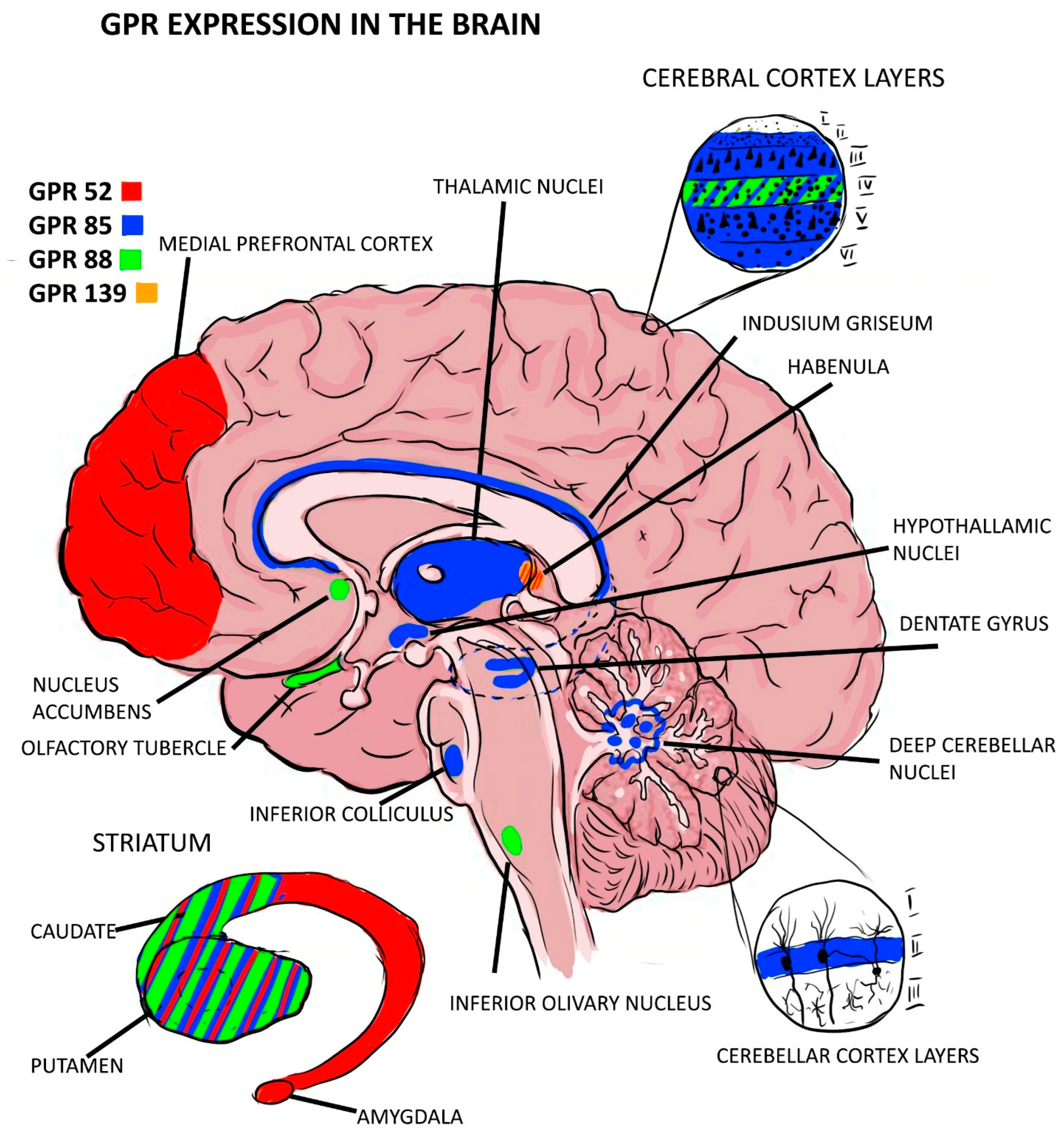

3.1.1. GPR-52

3.1.2. GPR-85

3.1.3. GPR-88

3.1.4. GPR-139

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpenter, W.T., Jr.; Buchanan, R.W. Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Kendler, K.S.; Neale, M.C. Schizophrenia as a Complex Trait: Evidence from a Meta-analysis of Twin Studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, D.P.; Goldsmith, C.A. Treatment of schizophrenia in the 21st Century: Beyond the neurotransmitter hy-pothesis. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattai, A.; Hosanagar, A.; Weisinger, B.; Greenstein, D.; Stidd, R.; Clasen, L.; Lalonde, F.; Rapoport, J.; Gogtay, N. Hippocampal volume development in healthy siblings of childhood-onset schizophrenia patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, A.M.; Owens, D.C.; Moorhead, W.J.; Whalley, H.C.; Stanfield, A.C.; Hall, J.; Johnstone, E.C.; Lawrie, S.M. Longitudinal volume reductions in people at high genetic risk of schizophrenia as they develop psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsson, T.; Suckling, J.; Maier, M.; Williams, S.C.; Bullmore, E.T.; Greenwood, K.E.; Fukuda, R.; Ron, M.A.; Toone, B.K. Structural abnormalities in frontal, temporal, and limbic regions and interconnecting white matter tracts in schizophrenic patients with prominent negative symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, T.J.; Johnstone, E.C.; Longden, A.; Owen, F. Dopamine and schizophrenia. Adv. Biochem. Psycho-Pharmacol. 1978, 19, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.M. Beyond the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia to three neural networks of psychosis: Dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. CNS Spectr. 2018, 23, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balu, D.T. The NMDA Receptor and Schizophrenia: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. Adv. Pharmacol. 2016, 76, 351–382. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, S.; Haque, E.; Jakaria, M.; Jo, S.-H.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in CNS: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Intervention in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Associated Cognitive Deficits. Cells 2020, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschet, C.; Dupuis, N.; Hanson, J. The G protein-coupled receptors deorphanization landscape. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 153, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Saito, T.; Takasaki, J.; Kamohara, M.; Sugimoto, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Tadokoro, M.; Matsumoto, S.-I.; Ohishi, T.; Furuichi, K. An evolutionarily conserved G-protein coupled receptor family, SREB, expressed in the central nervous system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 272, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellebrand, S.; Schaller, H.; Wittenberger, T. The brain-specific G-protein coupled receptor GPR85 with identical protein sequence in man and mouse maps to human chromosome 7q31. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gene Struct. Expr. 2000, 1493, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Maruyama, M.; Yao, S.; Shinohara, T.; Sakuma, K.; Imaichi, S.; Chikatsu, T.; Kuniyeda, K.; Siu, F.K.; Peng, L.S.; et al. Anatomical transcriptome of G protein-coupled receptors leads to the identification of a novel therapeutic candidate GPR52 for psychiatric disorders. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirvonen, J.; van Erp, T.G.; Huttunen, J.; Någren, K.; Huttunen, M.; Aalto, S.; Lönnqvist, J.; Kaprio, J.; Cannon, T.D.; Hietala, J. Striatal dopamine D1 and D2 receptor balance in twins at increased genetic risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2006, 146, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosal, S.; Hare, B.D.; Duman, R.S. Prefrontal Cortex GABAergic Deficits and Circuit Dysfunction in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Chronic Stress and Depression. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grottick, A.J.; Grayson, B.; Podda, G.; Idris, N.; Dorner-Ciossek, C.; Neill, J.; Hobson, S. T40. GPR52 Agonists Represent a Novel Approach to Treat Unmet Medical Need in Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellebrand, S.; Wittenberger, T.; Schaller, H.; Hermans-Borgmeyer, I. Gpr85, a novel member of the G-protein coupled receptor family, prominently expressed in the developing mouse cerebral cortex. Gene Expr. Patterns 2001, 1, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Straub, R.E.; Marenco, S.; Nicodemus, K.K.; Matsumoto, S.-I.; Fujikawa, A.; Miyoshi, S.; Shobo, M.; Takahashi, S.; Yarimizu, J.; et al. The evolutionarily conserved G protein-coupled receptor SREB2/GPR85 influences brain size, behavior, and vulnerability to schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6133–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kogan, J.H.; Gross, A.K.; Zhou, Y.; Walton, N.M.; Shin, R.; Heusner, C.L.; Miyake, S.; Tajinda, K.; Tamura, K.; et al. SREB2/GPR85, a schizophrenia risk factor, negatively regulates hippocampal adult neurogenesis and neurogenesis-dependent learning and memory. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 36, 2597–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, E.; Sambataro, F.; Mattay, V.S.; Callicott, J.H.; E Straub, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Weinberger, D.R.; Marenco, S. Effect of schizophrenia risk-associated alleles in SREB2 (GPR85) on functional MRI phenotypes in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massart, R.; Guilloux, J.; Mignon, V.; Sokoloff, P.; Diaz, J. Striatal GPR88 expression is confined to the whole projection neuron population and is regulated by dopaminergic and glutamatergic afferents. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logue, S.F.; Grauer, S.M.; Paulsen, J.; Graf, R.; Taylor, N.; Sung, M.A.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, Z.; Pulito, V.L.; Liu, F.; et al. The orphan GPCR, GPR88, modulates function of the striatal dopamine system: A possible therapeutic target for psychiatric disorders? Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009, 42, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingallinesi, M.; Galet, B.; Pegon, J.; Biguet, N.F.; Thi, A.D.; Millan, M.J.; la Cour, C.M.; Meloni, R. Knock-Down of GPR88 in the Dorsal Striatum Alters the Response of Medium Spiny Neurons to the Loss of Dopamine Input and L-3-4-Dyhydroxyphenylalanine. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Zompo, M.; Deleuze, J.; Chillotti, C.; Cousin, E.; Niehaus, D.; Ebstein, R.P.; Ardau, R.; Macé, S.; Warnich, L.; Mujahed, M.; et al. Association study in three different populations between the GPR88 gene and major psychoses. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2014, 2, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lee, G.; Kuei, C.; Yao, X.; Harrington, A.; Bonaventure, P.; Lovenberg, T.W.; Liu, C. GPR139 and Dopamine D2 Receptor Co-express in the Same Cells of the Brain and May Functionally Interact. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atienza, J.; Reichard, H.; Mulligan, V.; Cilia, J.; Monenschein, H.; Collia, D.; Ray, J.; Kilpatrick, G.; Brice, N.; Carlton, M.; et al. S39. GPR139 an Ophan Gpcr Affecting Negative Domains of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, S339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; MacDonald, M.L.; Elswick, D.E.; Sweet, R.A. The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia: Evidence from human brain tissue studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1338, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerton, A.; Grace, A.A.; Stone, J.; Bossong, M.G.; Sand, M.; McGuire, P. Glutamate in schizophrenia: Neurodevel-opmental perspectives and drug development. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 223, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bonaventure, P.; Lee, G.; Nepomuceno, D.; Kuei, C.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Joseph, V.; Sutton, S.W.; Eckert, W.; et al. GPR139, an Orphan Receptor Highly Enriched in the Habenula and Septum, Is Activated by the Essential Amino Acids l-Tryptophan and l-Phenylalanine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, H.; Watanabe, S.; Koshikawa, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Ichiba, H.; Nabeshima, T.; Fukushima, T. De-creased L-tryptophan concentration in distinctive brain regions of mice treated repeatedly with phencyclidine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 8137–8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serres, F.; Dassa, D.; Azorin, J.-M.; Jeanningros, R. Decrease in red blood cell l-tryptophan uptake in schizophrenic patients: Possible link with loss of impulse control. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1995, 19, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, K.; Uematsu, M.; Ofuji, M.; Morikiyo, M.; Kaiya, H. Substance P involved in mental disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1988, 12, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cronenwett, W.J.; Csernansky, J. Thalamic pathology in schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A Lieberman, J.; Girgis, R.R.; Brucato, G.; Moore, H.; Provenzano, F.; Kegeles, L.; Javitt, D.; Kantrowitz, J.; Wall, M.M.; Corcoran, C.M.; et al. Hippocampal dysfunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: A selective review and hypothesis for early detection and intervention. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1764–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cothren, T.O.; Evonko, C.J.; MacQueen, D.A. Olfactory Dysfunction in Schizophrenia: Evaluating Olfactory Abilities across Species. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 63, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCollum, L.A.; Roberts, R.C. Uncovering the role of the nucleus accumbens in schizophrenia: A postmortem analysis of tyrosine hydroxylase and vesicular glutamate transporters. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 169, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Abi-Dargham, A.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia, Dopamine and the Striatum: From Biology to Symptoms. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ősz, B.-E.; Jîtcă, G.; Sălcudean, A.; Rusz, C.M.; Vari, C.-E. Benzydamine—An Affordable Over-the-Counter Drug with Psychoactive Properties—From Chemical Structure to Possible Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Răchită, A.I.C.; Strete, G.E.; Sălcudean, A.; Ghiga, D.V.; Huțanu, A.; Muntean, L.M.; Suciu, L.M.; Mărginean, C. The Relationship between Psychological Suffering, Value of Maternal Cortisol during Third Trimester of Pregnancy and Breast-feeding Initiation. Medicina 2023, 59, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feier, A.M.; Portan, D.; Manu, D.R.; Kostopoulos, V.; Kotrotsos, A.; Strnad, G.; Dobreanu, M.; Salcudean, A.; Bataga, T. Primary MSCs for Personalized Medicine: Ethical Challenges, Isolation and Biocompatibility Evaluation of 3D Electrospun and Printed Scaffolds. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

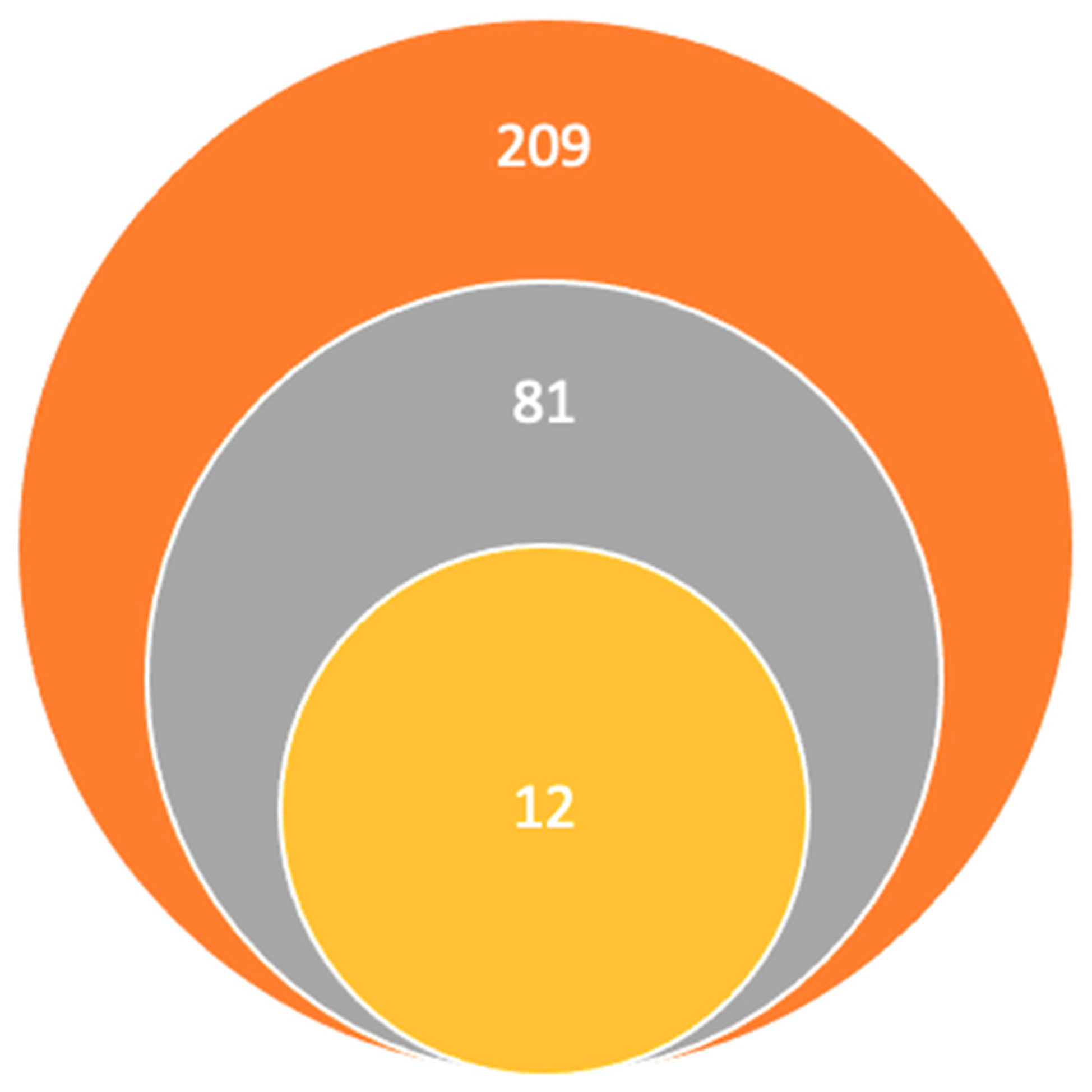

Titles and abstracts published in the last 5 years using keywords.

Titles and abstracts published in the last 5 years using keywords.  Studies remaining after the elimination of other titles for being unrelated, duplicates, and unavailable full texts.

Studies remaining after the elimination of other titles for being unrelated, duplicates, and unavailable full texts.  Articles included in the final study.

Articles included in the final study.

Titles and abstracts published in the last 5 years using keywords.

Titles and abstracts published in the last 5 years using keywords.  Studies remaining after the elimination of other titles for being unrelated, duplicates, and unavailable full texts.

Studies remaining after the elimination of other titles for being unrelated, duplicates, and unavailable full texts.  Articles included in the final study.

Articles included in the final study.

| GPR | Main Results | Tissue Distribution | Relationship to Schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPR-52 [13,14] | Is a druggable Gs-coupled receptor; has a 22-residue ECL2 that folds into a small module and occupies the orthosteric binding pocket of the receptor, establishing interactions with transmembrane helices to maintain its configuration | Exclusively in the brain, especially in the striatum. | Potentially protective |

| Agonists: 12c, 23a, 23d, 23e, 23f, and 23h Regulates various brain functions through activation of cAMPC-dependent pathways | |||

| KO group showed typical psychotic behaviors | |||

| GPR-52 receptor is selectively and dose-dependently activated by reserpine | |||

| GPR-52 agonists can reverse rat-induced phencyclidine (PCP) hyperlocomotion | |||

| GPR-85 [17,18,19,20] | Is a protein-coding gene. | In the central nervous system, highest expression in the thalamus, while it was hardly detectable in spinal cord and the corpus callosum. Is more intensely expressed in young neurons. | Potentially risky |

| Transgenic mice had a lower brain volume, an increase in the size of the cerebral ventricles, and the cortical neurons were smaller and compacted, with reduced arborizations. | |||

| After 2 weeks of birth, TG mice presented increased apoptotic levels | |||

| Human samples, two alleles of the GPR-85 gene were identified to be associated with schizophrenia and decrease in hippocampal cortex | |||

| GPR-88 [21,22,23,24] | Is a protein-coding gene. | In the striatum, olfactory tubercles and in the nucleus accumbens. | Potentially risky |

| Known agonists are: 2-PCCA, RTI-13951–33, and phenylglycinol derivatives. | |||

| Enables cytoskeletal motor activity. Involved in motor learning. | |||

| L-dopa treatment led to normalization of GPR-88 expression in striatopallidal and striatonigral MSNs in dopamine depleted mice through D1 and D2 receptor mediated mechanisms | |||

| Silencing of the GPR-88 gene in the nucleus accumbens reduces the typical manifestations of schizophrenia | |||

| Was directly associated with schizophrenia in a group study in South Africa Modulates the function of the dopamine system | |||

| GPR-139 [26] | The aromatic amino acids could be the endogenous signaling molecules for GPR-139. | In the CNS and the pituitary gland similar to the D2 dopamine receptors. | Potentially protective |

| Knock-out mice were significantly impaired in models that reflect aspects of negative symptoms | |||

| The small molecule agonist was observed to reverse deficits in models of schizophrenia including cognition in a subchronic PCP induced attentional set-shifting paradigm and social interaction | |||

| Plays a protective role in the development of negative symptoms in schizophrenia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalinovic, R.; Pascariu, A.; Vlad, G.; Nitusca, D.; Sălcudean, A.; Sirbu, I.O.; Marian, C.; Enatescu, V.R. Involvement of the Expression of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Schizophrenia. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17010085

Kalinovic R, Pascariu A, Vlad G, Nitusca D, Sălcudean A, Sirbu IO, Marian C, Enatescu VR. Involvement of the Expression of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Schizophrenia. Pharmaceuticals. 2024; 17(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalinovic, Raluka, Andrei Pascariu, Gabriela Vlad, Diana Nitusca, Andreea Sălcudean, Ioan Ovidiu Sirbu, Catalin Marian, and Virgil Radu Enatescu. 2024. "Involvement of the Expression of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Schizophrenia" Pharmaceuticals 17, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17010085

APA StyleKalinovic, R., Pascariu, A., Vlad, G., Nitusca, D., Sălcudean, A., Sirbu, I. O., Marian, C., & Enatescu, V. R. (2024). Involvement of the Expression of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Schizophrenia. Pharmaceuticals, 17(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17010085