Oral Wound Healing Potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Cell Viability—MTT Assay

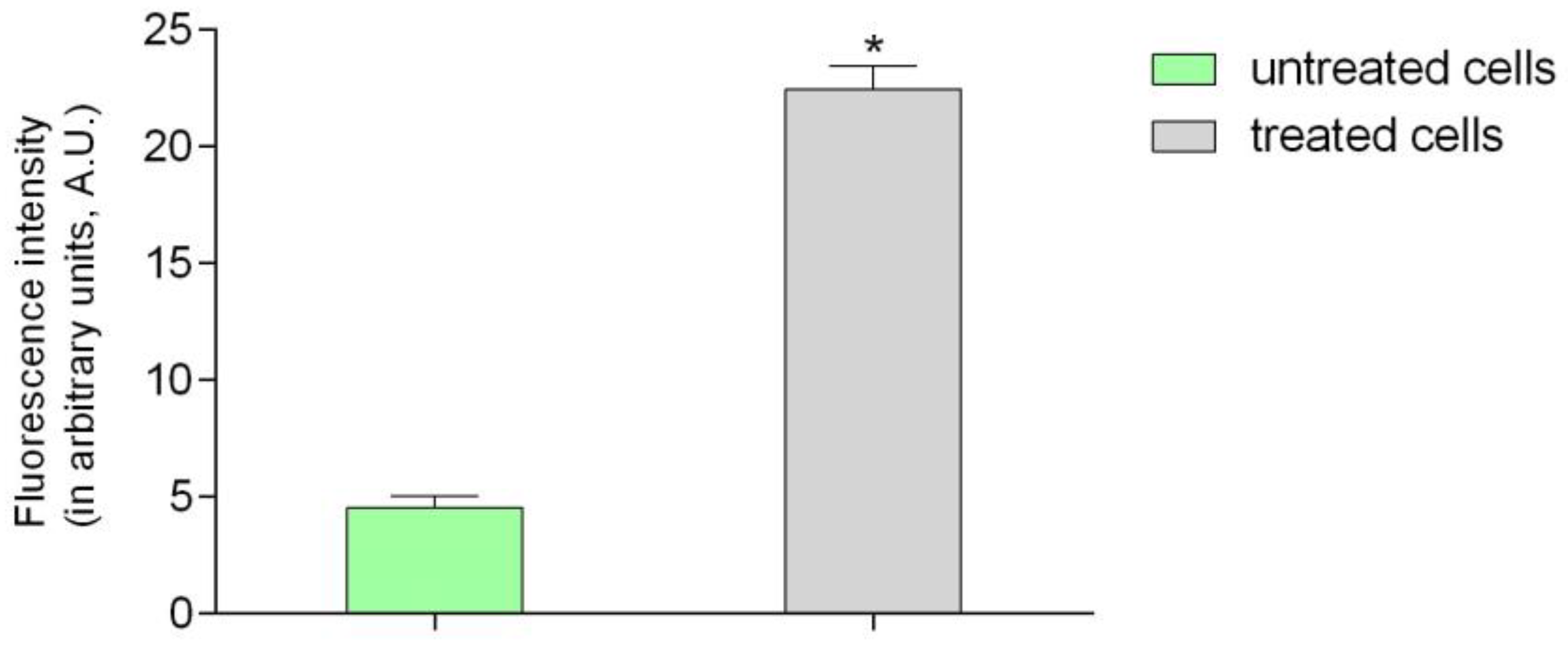

2.2. Confocal Laser Microscopy Study

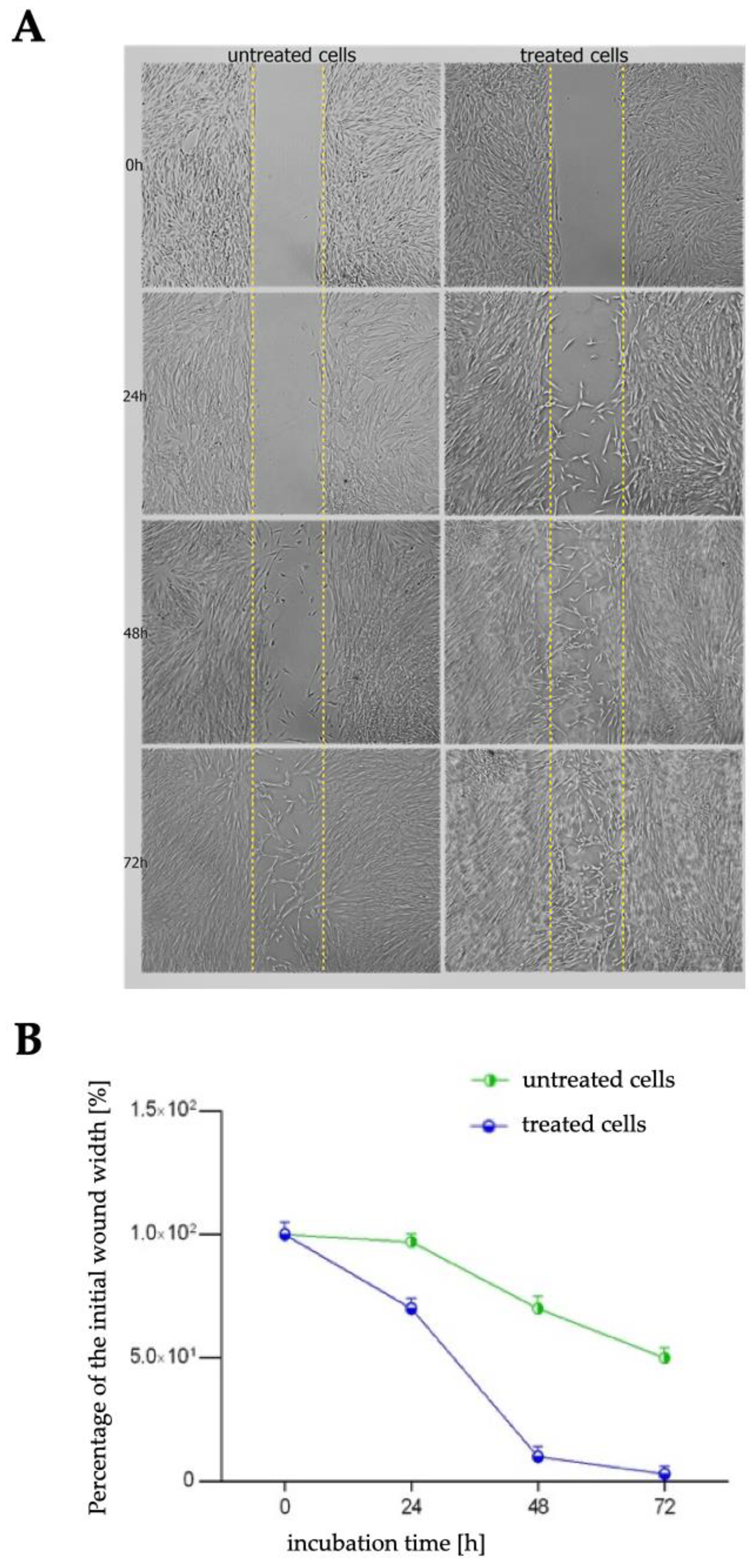

2.3. Wound Healing Assay

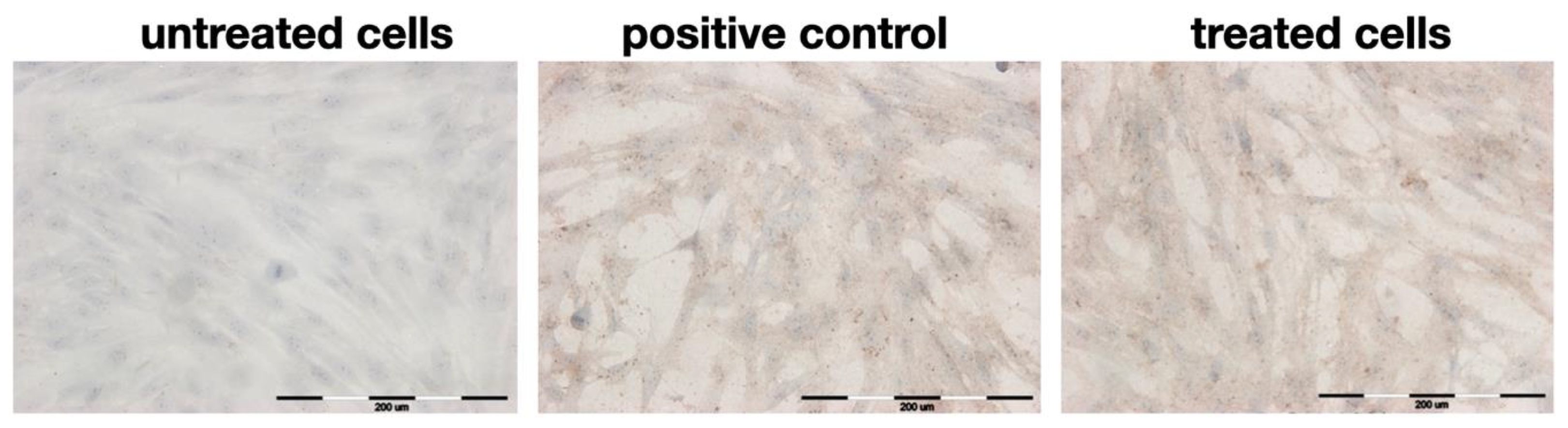

2.4. Immunocytochemical Staining

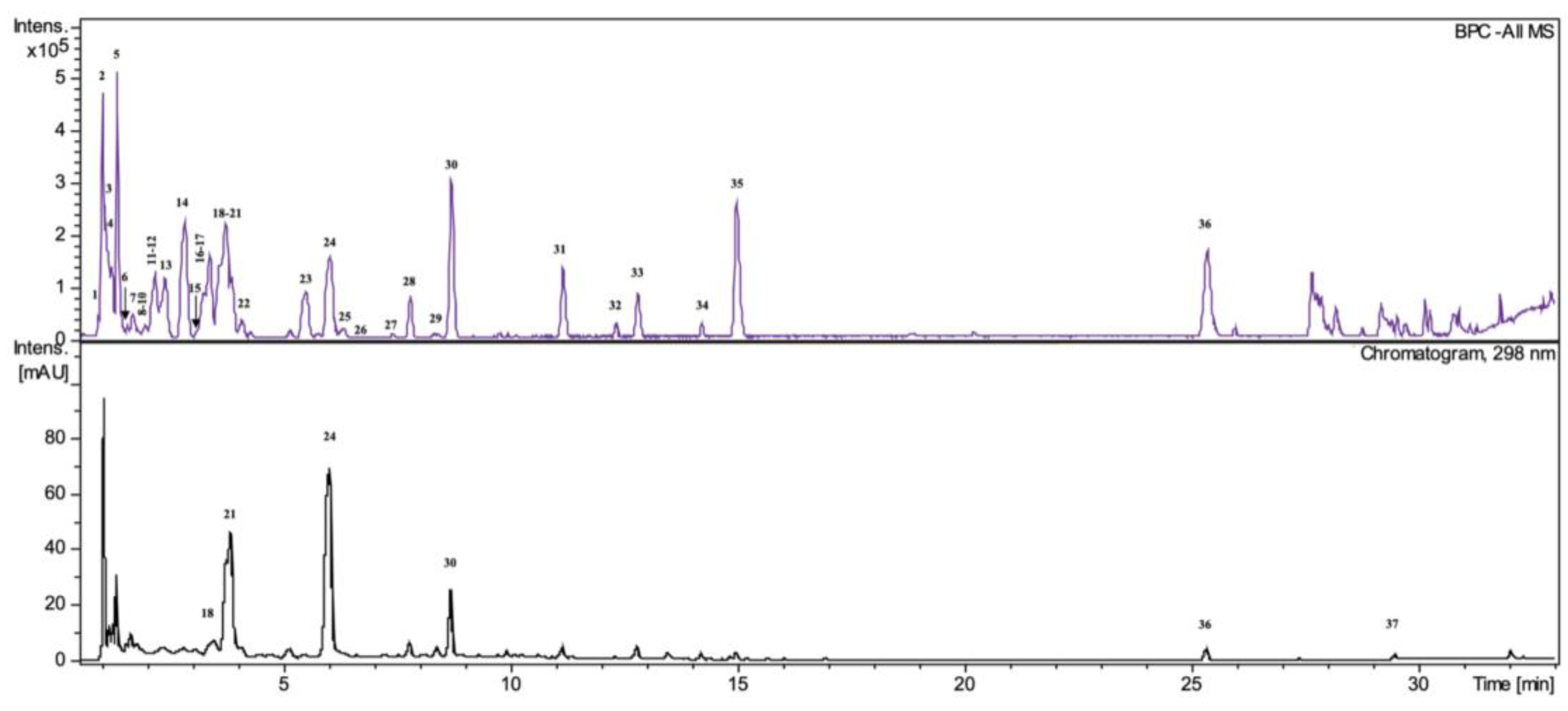

2.5. HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-TOF-MS Analysis

2.6. Total Polyphenols and Tannins Content

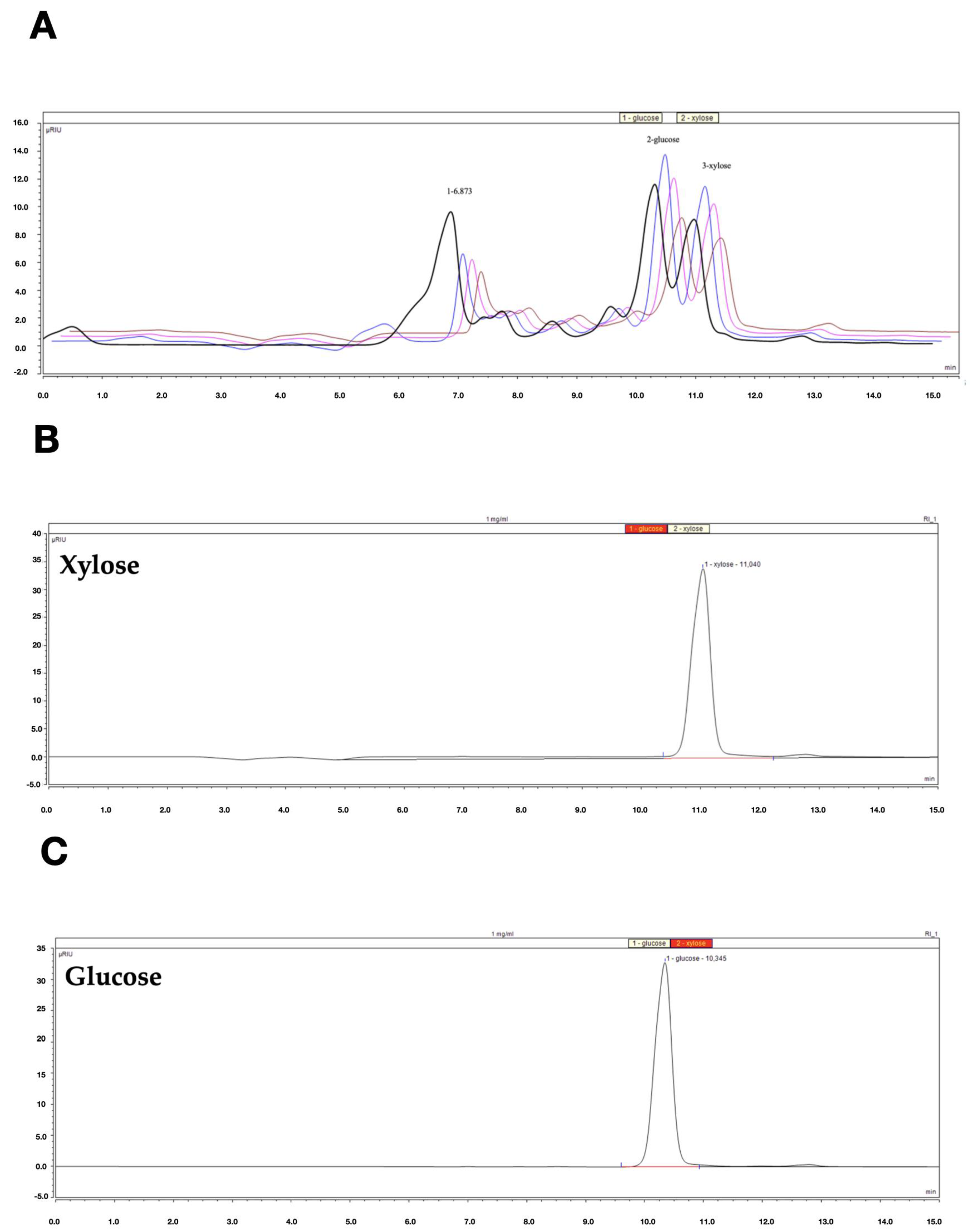

2.7. HPLC-RI Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Decoction Preparation

3.2. Cell Culture

3.3. Cell Viability Assay

3.4. Confocal Laser Microscopy Study

3.5. In Vitro Wound Healing Assay

3.6. Immunocytochemical Staining

3.7. HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-QTOF-MS Analysis

3.8. Total Polyphenols and Tannins Content

3.9. HPLC-RI Analysis

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Pharmacopoeia, 9th ed.; European Director- ate for the Quality of Medicines: Strasburg, France, 2017; pp. 1481–1483.

- Peng, W.; Qin, R.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and potential application of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb.et Zucc.: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Granica, S.; Hadzik, J.; Matkowski, A. Phytochemical Diversity in Rhizomes of Three Reynoutria Species and their Antioxidant Activity Correlations Elucidated by LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Zmudzinski, M.; Matkowski, A.; Preissner, R.; Kęsik-Brodacka, M.; Hadzik, J.; Drag, M.; Abel, R. Reynoutria Rhizomes as a Natural Source of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors–Molecular Docking and In Vitro Study. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Hadzik, J.; Fleischer, M.; Choromańska, A.; Sterczała, B.; Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Saczko, J.; Gałczyńska-Rusin, M.; Gedrange, T.; Matkowski, A. Chemical composition of east Asian invasive knotweeds, their cytotoxicity and antimicrobial efficacy against cariogenic pathogens: An in-vitro study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 3279–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alperth, F.; Melinz, L.; Fladerer, J.P.; Bucar, F. Uhplc analysis of reynoutria japonica houtt. Rhizome preparations regarding stilbene and anthranoid composition and their antimycobacterial activity evaluation. Plants 2021, 10, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matkowski, A.; Pitułaj, A.; Sterczała, B.; Olchowy, C.; Szewczyk, A.; Choromańska, A. In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, H.; Krenn, L.; Jiang, R.; Sutherland, I.; Ignatova, S.; Marmann, A.; Liang, X.; Sendker, J. The potential of metabolic fingerprinting as a tool for the modernisation of TCM preparations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 140, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranasukhon, W.; Athikomkulchai, S.; Tadtong, S.; Chittasupho, C. Wound healing activity of Pluchea indica leaf extract in oral mucosal cell line and oral spray formulation containing nanoparticles of the extract. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, E.A.; Allan, R.B. Review article: Oral ulceration--aetiopathogenesis, clinical diagnosis and management in the gastrointestinal clinic. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranasin, P.; Mizutani, K.; Iwasaki, K.; Mahasarakham, C.P.N.; Kido, D.; Takeda, K.; Izumi, Y. High glucose-induced oxidative stress impairs proliferation and migration of human gingival fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matkowski, A.; Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Hadzik, J. Proanthocyanidins and Flavan-3-ols in the Prevention and Treatment of Periodontitis—Immunomodulatory Effects, Animal and Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, M.; Oyarzun, A.; Smith, P.C. Defective wound-healing in aging gingival tissue. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, A.I.; Fuller, J.M.; Willett, N.J.; Goudy, S.L. Oral wound healing models and emerging regenerative therapies. Transl. Res. 2021, 236, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Fleischer, M.; Pitułaj, A.; Hadzik, J.; Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Bortkiewicz, O.; Dominiak, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Evaluation of the three methods of bacterial decontamination on implants with three different surfaces. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clément, C.; Orsi, G.A.; Gatto, A.; Boyarchuk, E.; Forest, A.; Hajj, B.; Miné-Hattab, J.; Garnier, M.; Gurard-Levin, Z.A.; Quivy, J.P.; et al. High-resolution visualization of H3 variants during replication reveals their controlled recycling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komar, D.; Juszczynski, P. Rebelled epigenome: Histone H3S10 phosphorylation and H3S10 kinases in cancer biology and therapy. Clin. Epigenetics 2020, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Granica, S.; Domaradzki, K.; Pecio, Ł.; Matkowski, A. Isolation and Determination of Phenolic Glycosides and Anthraquinones from Rhizomes of Various Reynoutria Species. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, P.B.S.; de Oliveira, W.F.; dos Santos Silva, P.M.; dos Santos Correia, M.T.; Kennedy, J.F.; Coelho, L.C.B.B. Skincare application of medicinal plant polysaccharides—A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Niu, Y.; Xing, P.; Wang, C. Bioactive polysaccharides from natural resources including Chinese medicinal herbs on tissue repair. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.L.; Lin, J.A.; Chen, S.Y.; Lin, J.H.; Lin, H.T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yen, G.C. Effects of Hsian-tsao (: Mesona procumbens Hemsl.) extracts and its polysaccharides on the promotion of wound healing under diabetes-like conditions. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Pi, F.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H. Extraction, purification, structural characteristics, biological activities and pharmacological applications of acemannan, a polysaccharide from aloe vera: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jettanacheawchankit, S.; Sasithanasate, S.; Sangvanich, P.; Banlunara, W.; Thunyakitpisal, P. Acemannan stimulates gingival fibroblast proliferation; expressions of keratinocyte growth factor-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, and type I collagen; and wound healing. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 109, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majtan, J.; Jesenak, M. β-Glucans: Multi-functional modulator of wound healing. Molecules 2018, 23, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterczala, B.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J.; Dominiak, M. The effect of dental gel formulation on human primary fibroblasts—An in vitro study. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2020, 58, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak, A.; Zmora, P.; Matkowski, A.; Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Pers-Kamczyc, E.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Bryszak, M.; Szumacher-Strabel, M. Tannins from sanguisorba officinalis affect in vitro rumen methane production and fermentation. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2016, 26, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Granica, S.; Abel, R.; Czapor-Irzabek, H.; Matkowski, A. Analysis of antioxidant polyphenols in loquat leaves using HPLC-based activity profiling. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pińkowska, H.; Krzywonos, M.; Wolak, P.; Złocińska, A. Pectin and Neutral Monosaccharides Production during the Simultaneous Hydrothermal Extraction of Waste Biomass from Refining of Sugar—Optimization with the Use of Doehlert Design. Molecules 2019, 24, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time of the Incubation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| untreated cells | 3% | 30% | 50% |

| treated cells | 30% | 90% | 97% |

| Sample | Intensity of Staining | HGF Stained [% ± SD] |

|---|---|---|

| untreated cells | − | 96 ± 2 |

| positive control | ++ | 95 ± 1.5 * |

| decoction | ++ | 99 ± 1 * |

| Nr. | Compound | Rt. [min] | UV Max [nm] | m/z [M-H]− | Error (ppm) | Ion Formula | MS2 Main-Ion (Relative Intensity %) | MS2 Fragments (Relative Intensity %) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown carbohydrate | 1.0 | ND | 341.1093 | −1.0 | C12H21O11 | 113.0239(100) | 119(80), 101(65), 179 (28), 173(21) | HMDB0000258 |

| 2 | Unknown carbohydrate | 1.05 | ND | 719.2028 | 1.8 | C30H39O20 | 377.0864(100) | 379(26), 341(13), 215 (1.9), 179(0.2) | - |

| 3 | Unknown | 1.1 | ND | 439.0815 | 4.5 | C26H15O7 | 96.9632(100) | 241(2) | - |

| 4 | Organic acid e.g., malic acid | 1.15 | ND | 133.0145 | −2.2 | C4H5O5 | 115.0058(100) | HMDB0000156 | |

| 5 | Organic acid e.g., citric acid | 1.3 | ND | 191.0200 | −1.4 | C6H7O7 | 111.0109(100) | HMDB0000094 | |

| 6 | Unknown | 1.57 | 225, 280 | 443.1931 | −1.9 | C21H31O10 | 189.0588(100) | 119(7), 113(7), 101 (7) | - |

| 7 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 1.6–1.8 | 225, 280 | 577.1358 | −1.1 | C30H25O12 | 289.0737(100) | 407(60), 125(30), 425(18) | [3] |

| 8 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 1.8–1.9 | 225, 280 | 865.197 | 1.8 | C45H37O18 | 575(100) | 287(92), 577(79), 695(57) | [3] |

| 9 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 1.9–2.0 | 225, 280 | 577.1349 | 0.4 | C30H25O12 | 289.0719(100) | 407(68), 125(42), 425(20) | [3] |

| 10 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 2.0–2.1 | 225, 280 | 865.1983 | 0.3 | C45H37O18 | 577.1353(100) | 287(90), 575(87), 865(75), 425(58), 289(45), 695(44), 713(42) | [3] |

| 11 | Catechin | 2.1 | 225, 280 | 289.0721 | −1.1 | C15H13O6 | 123.0452(100) | 109(92), 125(70), 245(35) | [3] |

| 12 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 2.2 | 225, 280 | 577.1356 | −0.8 | C30H25O12 | 289.0744(100) | 407(60), 125(34), 425(19) | [3] |

| 13 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 2.4 | 225, 280 | 577.1363 | −1.9 | C30H25O12 | 289.0744(100) | 407(61), 125(39), 425(16) | [3] |

| 14 | Epicatechin | 2.8 | 225, 280 | 289.0723 | −0.8 | C15H13O6 | 109.0292(100) | 123(93), 221(80), 125(76) | [3] |

| 15 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 3.15 | 225, 280 | 865.1966 | 2.3 | C45H37O18 | 577.1344(100) | 287(85), 575(77), 865(64), 425(55), 713(44), 413(41), 695(40) | [3] |

| 16 | Unknown | 3.25 | 280 | 499.1293 | 2.3 | C18H27O16 | 499.1298(100) | 97(10), 111(6) | - |

| 17 | Unknown | 3.38 | 280 | 499.1291 | 2.6 | C18H27O16 | 499.1299(100) | 97(9), 111(5) | - |

| 18 | Piceatannol glucoside | 3.4 | 220, 290, 318 | 405.1187 | 0.9 | C20H21O9 | 243.0671(100) | 244(15), 245(2), 201(1) | [19] |

| 19 | Unknown | 3.6 | 282, 325 | 439.1085 | 1.8 | C16H23O14 | 439.1089(100) | 97(21), 424(2) | - |

| 20 | Procyanidin dimer monogallate | 3.7 | 225, 280 | 729.1448 | 1.8 | C37H29O16 | 407.0787(100) | 289(46), 577(29), 451(21) | [3] |

| 21 | Resveratrolside | 3.8 | 220, 304, 315 | 389.1237, 435.1291 [M+COO]− | 1.2 | C20H21O8 | 227.0713(100) | 228(16), 225(9), 185(2) | [19] |

| 22 | Procyanidin dimer monogallate | 4.1 | 225, 280 | 729.1446 | 2.1 | C37H29O16 | 407.0777(100) | 289(71), 577(47), 441(31), 451(27) | [3] |

| 23 | Unknown | 5.5 | 220, 275 | 269.0147 | 1.3 | C7H9O11 | 189.0584 (100) | - | |

| 24 | Piceid | 6.0 | 220, 304, 315 | 389.1245 | −0.8 | C20H21O8 | 227.0716(100) | 228(13), 185(2), 225(0.5) | [19] |

| 25 | Epicatechin-3-O-gallate | 6.3 | 220, 279 | 441.0825 | 0.6 | C22H17O10 | 169.0145(100) | 289(51), 125(22), 245(14) | [19] |

| 26 | Procyanidin trimer monogallate | 6.7–6.8 | 225, 280 | 1017.2127 | −3.1 | C52H41O22 | 729.1431(100) | 577(31), 865(30), 287(28), 441(19) | [3] |

| 27 | Procyanidin tetramer monogallate | 7.3 | 225, 280 | 652.1307 [M−2H]2−, 1305.2673 | −6.2 | C67H53O28 | 125.0241(100) | 169(94), 289(52), 407(25), 451(11), 577(7), 729(6) | [3] |

| 28 | Resveratrol hexoside | 7.8 | 220, 304, 315 | 389.1242 | −0,1 | C20H21O8 | 227.0712(100) | 228(11), 185(1), 143(0.5) | [19] |

| 29 | Resveratrol derivative | 8.4 | 220, 282, 325 | 431.1356 | −2.0 | C22H23O9 | 227.0722(100) | 228(14), 185(1) | [19] |

| 30 | Resveratrol hexoside | 8.7 | 220, 304, 315 | 389.1249 | −1.9 | C20H21O8 | 227.0718(100) | 228(15), 185(2), 143(0.5) | [19] |

| 31 | Unknown | 11.2 | 220, 279, 307 | 253.0513 | −2.5 | C15H9O4 | 253.0513(100) | 254 (17), 224(9), 209(7), 197(3), 135(3) | - |

| 32 | Torachrysone- hexoside | 12.3 | 226, 266, 325sh | 407.1359 | −1.1 | C20H23O9 | 245.0845(100) | 246(14), 230(11) | [19] |

| 33 | Emodin-glucoside | 12.8 | 221, 269, 281, 423 | 431.099 | −1.5 | C21H19O10 | 269.0465(100) | 431(50),311(5) | [19] |

| 34 | Emodin-8-O-(6′-O-malonyl)-glucoside | 14.2 | 220, 281, 423 | 517.0991 | −0.7 | C24H21O13 | 473.1098(100) | 269(68), 311(3) | [19] |

| 35 | Sulfonyl torachrysone | 14.8 | 220, 312 | 325.0395 | −2.3 | C14H13O7S | 245.0829(100) | 230 (34) | [6] |

| 36 | Emodin | 25.4 | 221, 248, 267, 288, 430 | 269.0464 | −3.1 | C15H9O5 | 269.0464(100) | 225(29), 241(10), 197(2), 181(1) | [19] |

| 37 | Physcion * | 29.5 | 222, 266, 288, 430 | 285.0757 [M-H]+ | −1.9 | C16H13O5 [M-H]+ | - | [19] |

| Analyte | R. japonica Decoction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μg/mL of Liquid Decoction) | %CV | (mg/g of Dry Decoction) | %CV | (mg/g Dry Plant Material) | |

| Piceid | 22.60 | 0.23 | 4.52 | 0.23 | 0.83 |

| Resveratrol | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vanicoside B | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vanicoside A | - | - | - | - | - |

| Emodin | 1.41 * | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Physcion | 1.26 * | 2.31 | 0.25 | 2.31 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadzik, J.; Choromańska, A.; Karolewicz, B.; Matkowski, A.; Dominiak, M.; Złocińska, A.; Nawrot-Hadzik, I. Oral Wound Healing Potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16020267

Hadzik J, Choromańska A, Karolewicz B, Matkowski A, Dominiak M, Złocińska A, Nawrot-Hadzik I. Oral Wound Healing Potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study. Pharmaceuticals. 2023; 16(2):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16020267

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadzik, Jakub, Anna Choromańska, Bożena Karolewicz, Adam Matkowski, Marzena Dominiak, Adrianna Złocińska, and Izabela Nawrot-Hadzik. 2023. "Oral Wound Healing Potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study" Pharmaceuticals 16, no. 2: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16020267

APA StyleHadzik, J., Choromańska, A., Karolewicz, B., Matkowski, A., Dominiak, M., Złocińska, A., & Nawrot-Hadzik, I. (2023). Oral Wound Healing Potential of Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma et Radix Decoction—In Vitro Study. Pharmaceuticals, 16(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16020267