Genus Lepisanthes: Unravelling Its Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Botany of Genus Lepisanthes

3. Traditional Uses of Genus Lepisanthes

4. Phytochemistry

5. Pharmacological Activity

5.1. Antioxidant Activities

5.2. Antimicrobial Activities

5.3. Antihyperglycemic Activities

5.4. Antidiarrheal Activities

5.5. Analgesic Activities

5.6. Antimalarial Activities

6. Toxicity

7. Future Perspective

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sofowora, A.; Ogunbodede, E.; Onayade, A. The Role and Place of Medicinal Plants in the Strategies for Disease Prevention. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 10, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. The Promotion and Development of Traditional Medicine; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Boy, H.I.A.; Rutilla, A.J.H.; Santos, K.A.; Ty, A.M.T.; Yu, A.I.; Mahboob, T.; Tangpoong, J.; Nissapatorn, V. Recommended Medicinal Plants as Source of Natural Products: A Review. Digit. Chinese Med. 2018, 1, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, S.Z.; Ghani, N.A.; Ismail, N.H.; Bihud, N.V.; Rasol, N.E. Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activities of Lepisanthes Genus: A Review. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 5, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, S.K.; Zainol, M.K.; Mohd, Z.Z.; Hamzah, Y.; Mohdmaidin, N. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities in the Fruit Peel, Flesh and Seed of Ceri Terengganu (Lepisanthes Alata Leenh.). Food Res. 2020, 4, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazalli, M.N.; Talib, N.; Mohammad, A.L. Leaf Micro-Morphology of Lepisanthes Blume (Sapindaceae) in Peninsular Malaysia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1940, 020038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepisanthes Alata. Available online: https://www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com/lepisanthes-alata/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Boonsuk, B.; Chantaranothai, P. A New Record of Lepisanthes Blume for Thailand and Lectotypification of Two Names in Otophora Blume (Sapindaceae). Thai For. Bull. 2016, 44, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karunamoorthi, K.; Jegajeevanram, K.; Vijayalakshmi, J.; Mengistie, E. Traditional Medicinal Plants: A Source of Phytotherapeutic Modality in Resource-Constrained Health Care Settings. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 18, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomford, N.E.; Senthebane, D.A.; Rowe, A.; Munro, D.; Seele, P.; Maroyi, A.; Dzobo, K. Natural Products for Drug Discovery in the 21st Century: Innovations for Novel Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadijah, H.; Razali, M.; Anas, M.; Aisyah, R.; Shukri, M.A. Potential Use of Ceri Terengganu For Fuctional Food: A Preliminary Study on Its Cytotoxicity Aspect. 2020, 10. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/POTENTIAL-USE-OF-CERI-TERENGGANU-FOR-FUNCTIONAL-%3A-A-Hadijah/307d9d00631f593c9a10a8685160165f874dda50 (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Eswani, N.; Abd Kudus, K.; Nazre, M.; Awang Noor, A.G.; Ali, M. Medicinal Plant Diversity and Vegetation Analysis of Logged over Hill Forest of Tekai Tembeling Forest Reserve, Jerantut, Pahang. J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 2, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Choudhury, M.S.; Hossain, M.S.; Haque, M.A.; Seraj, S.; Rahmatullah, M. Ethnographic Information and Medicinal Formulations of a Mro Community of Gazalia Union in the Bandarbans District of Bangladesh. Am. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 6, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, M.; Balasubramanian, P. Ethnomedicinal Uses of Sthalavrikshas (Temple Trees) in Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2012, 10, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomchid, P.; Nasomjai, P.; Kanokmedhakul, S.; Boonmak, J.; Youngme, S.; Kanokmedhakul, K. Bioactive Lupane and Hopane Triterpenes from Lepisanthes Senegalensis. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.; Akther, F.; Ayman, U.; Sifa, R.; Jahan, I.; Sarker, M.; Chakma, S.K.; Podder, P.K.; Khatun, Z.; Rahmatullah, M. Ethnomedicinal Investigations among the Sigibe Clan of the Khumi Tribe of Thanchi Sub-District in Bandarban District of Bangladesh. Am. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 6, 378–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dior, A.; Patrick, V.; Bassene, E.; Nicolaas, J. Phytochemical Screening, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxicity Studies of Ethanol Leave Extract of Aphania Senegalensis (Sapindaceae). Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 14, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bruschi, P.; Urso, V.; Solazzo, D.; Tonini, M.; Signorini, M.A. Traditional Knowledge on Ethno-Veterinary and Fodder Plants in South Angola: An Ethnobotanic Field Survey in Mopane Woodlands in Bibala, Namibe Province. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2017, 111, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.A.H.; Ismail, A.; Kassim, N.K.; Hamid, M.; Ali, M.S.M. Phenolic Profiling and Evaluation of in Vitro Antioxidant, α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Inhibitory Activities of Lepisanthes Fruticosa (Roxb) Leenh Fruit Extracts. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.K. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 6, Fruits; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 656–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salusu, H.D.; Ariani, F.; Obeth, E.; Rayment, M.; Budiarso, E.; Kusuma, I.W.; Arung, E.T. Phytochemical Screening and Antioxidant Activity of Selekop (Lepisanthes Amoena) Fruit. Agrivita 2017, 39, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuspradini, H.; Susanto, D.; Mitsunaga, T. Phytochemical and Comparative Study of Anti Microbial Activity of Lepisanthes Amoena Leaves Extract. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2012, 2, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, N.A.; Mat, N.; Mahmud, K. Traditional Knowledge and Botanical Description of Edible Bitter Plants from Besut, Terengganu, Malaysia. J. Agrobiotechnol. 2020, 11, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.R.; Das, S.; Alam, M.; Rahman, A. Documentation of Wild Edible Minor Fruits Used by the Local People of Barishal, Bangladesh with Emphasis on Traditional Medicinal Values. J. Bio Sci. 2019, 27, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matius, P.; Diana, R. Sutedjo Inventarisasi Tumbuhan Berhasiat Obat Yang Dimanfaatkan Suku Dayak Benuaq Di Desa Muara Nilik. J. Tengkawang 2021, 11, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kurmukov, A.G. Phytochemistry of Medicinal Plants. Med. Plants Cent. Asia Uzb. Kyrg. 2013, 1, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wong, A.I.C.; Wu, J.; Abdul Karim, N.B.; Huang, D. Lepisanthes Alata (Malay Cherry) Leaves Are Potent Inhibitors of Starch Hydrolases Due to Proanthocyanidins with High Degree of Polymerization. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Hossain, A.; Shamim, A.; Rahman, M.M. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Evaluation of Ethanolic Extract of Lepisanthes Rubiginosa, L. Leaves. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anggraini, T.; Wilma, S.; Syukri, D.; Azima, F. Total Phenolic, Anthocyanin, Catechins, DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity, and Toxicity of Lepisanthes Alata (Blume) Leenh. Int. J. Food Sci. 2019, 9703176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gui, Y.; Huang, D. Impact of Maturity of Malay Cherry (Lepisanthes Alata) Leaves on the Inhibitory Activity of Starch Hydrolases. Molecules 2017, 22, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batubara, I.; Mitsunaga, T.; Ohashi, H. Screening Antiacne Potency of Indonesian Medicinal Plants: Antibacterial, Lipase Inhibition, and Antioxidant Activities. J. Wood Sci. 2009, 55, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, F.; Kuspradini, H.; Mitsunaga, T. Estimation of Total Phenol Content and Antimicrobial Activity in Different Leaf Stage of Lepisanthes Amonea. Adv. Biol. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, S.; Naim, Z.; Sarwar, G. Pharmacological, Phytochemical and Physicochemical Properties of Methanol Extracts of Erioglossum Rubiginosum Barks. J. Health Sci. 2013, 3, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Widyawaruyanti, A.; Puspita Devi, A.; Fatria, N.; Tumewu, L.; Tantular, I.S.; Fuad Hafid, A. In Vitro Antimalarial Activity Screening of Several Indonesian Plants Using HRP2 Assay. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, N.; Jeya, M.; Aroumugame, S.; Arumugam, P.; Sagadevan, E. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Leaves of Lepisanthes Tetraphylla and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial Activity against Drug Resistant Clinical Isolates. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2012, 3, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Vasudeva, N. Review on Antioxidants and Evaluation Procedures. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunitha, D.; Abbasi, A.; Schaich, K.M. A Review on Antioxidant Methods Related Papers. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2016, 9, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahuddin, M.A.H.; Othman, Z.; Ying, J.C.L.; Noor, E.S.M.; Idris, S. Antioxidant Activity and Phytochemical Content of Fresh and Freeze-Dried Lepisanthes Fruticosa Fruits at Different Maturity Stages. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jun, M.; Fu, H.Y.; Hong, J.; Wan, X.; Yang, C.S.; Ho, C.T. Comparison of Antioxidant Activities of Isoflavones from Kudzu Root (Pueraria Lobata Ohwi). J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 2117–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Oh, Y.J.; Lim, J.; Youn, M.; Lee, I.; Pak, H.K.; Park, W.; Jo, W.; Park, S. AFM Study of the Differential Inhibitory Effects of the Green Tea Polyphenol (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Hidayathulla, S.; Rehman, M.T.; Elgamal, A.A.; Al-Massarani, S.; Razmovski-Naumovski, V.; Alqahtani, M.S.; El Dib, R.A.; Alajmi, M.F. Alpha-Amylase and Alpha-Glucosidase Enzyme Inhibition and Antioxidant Potential of 3-Oxolupenal and Katononic Acid Isolated from Nuxia oppositifolia. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, M.; Valerio, I.; Sánchez, R.; Mora, V.; Bagnarello, V.; Martínez, L.; Gonzalez, A.; Vanegas, J.C.; Apestegui, Á. In Vitro Antimalarial Activity of Extracts of Some Plants from a Biological Reserve in Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2012, 60, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Plant Parts | Traditional Medicine Applications | Region/Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. tetraphylla | Leaves | Cough and fever | Malaysia [12] |

| Root | Diarrhea | Bangladesh [13] | |

| Seed | Dandruff | India [14] | |

| L. senegalensis | Root | Malaria, fever with vertigo, chest pain, and nosebleed | Thailand [15] |

| Root | Diarrhea | Bangladesh [16] | |

| Leaves | Bacterial and fungal infections, pain, inflammation, and asthenia | Senegal [17] | |

| L. fruticosa | Root | Itchiness and fever | Malaysia [19,20] |

| Root | Rheumatism, backache, and to maintain vitality | Sarawak [20] | |

| L. amoena | Leaves | Facial skin problems | East Kalimantan [22] |

| L. rubiginosa | Leaves | Muscle soreness | Terengganu [23] |

| Fruit | Fever, flatulence, and postpartum blues | Terengganu [23] | |

| Fruit | Diarrhea, dysentery, and jaundice | Bangladesh [24] | |

| L. alata | Leaves | Skin itchiness due to scabs | East Kalimantan [25] |

| Ref | Type | Compound | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

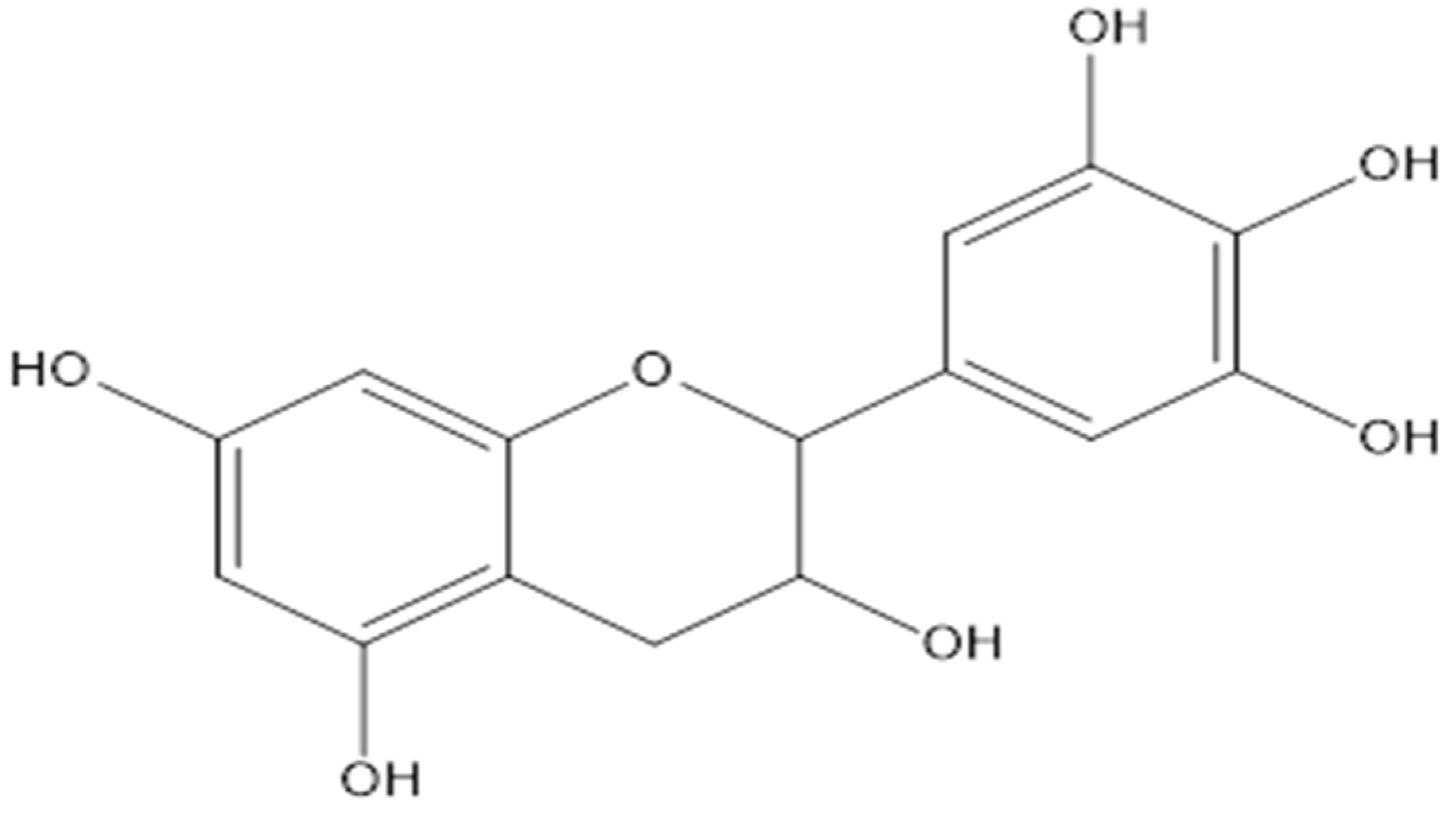

| [19,27] | Flavanol | Gallocatechin | L. fruticosa, L. alata |

| Epicatechin | L. fruticosa, L. alata | ||

| [19] | Flavanonol | Dihydrokaempferol-5-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | L. fruticosa |

| 2,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone-4′-O-β-D-glucoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Neoastilbin | L. fruticosa | ||

| Flavonol | Quercetin-3,7-O-β-D-diglucopyranoside | L. fruticosa | |

| Quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Kaempferol-3,7-diglucoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Quercetin-3-galactoside-7-glucoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Rutin | L. fruticosa | ||

| Quercetin-3-sulphate | L. fruticosa | ||

| Buddlenoid A | L. fruticosa | ||

| Hibiscetin-3-O-glucoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| Flavone | 5,2′-dihydroxy-6,7,8-trimethoxyflavone-2′-O-β-D-glucoside | L. fruticosa | |

| Isoflavone | Genistein-7,4′-di-O-β-D-glucoside | L. fruticosa | |

| Anthocyanin | Luteolinidin | L. fruticosa | |

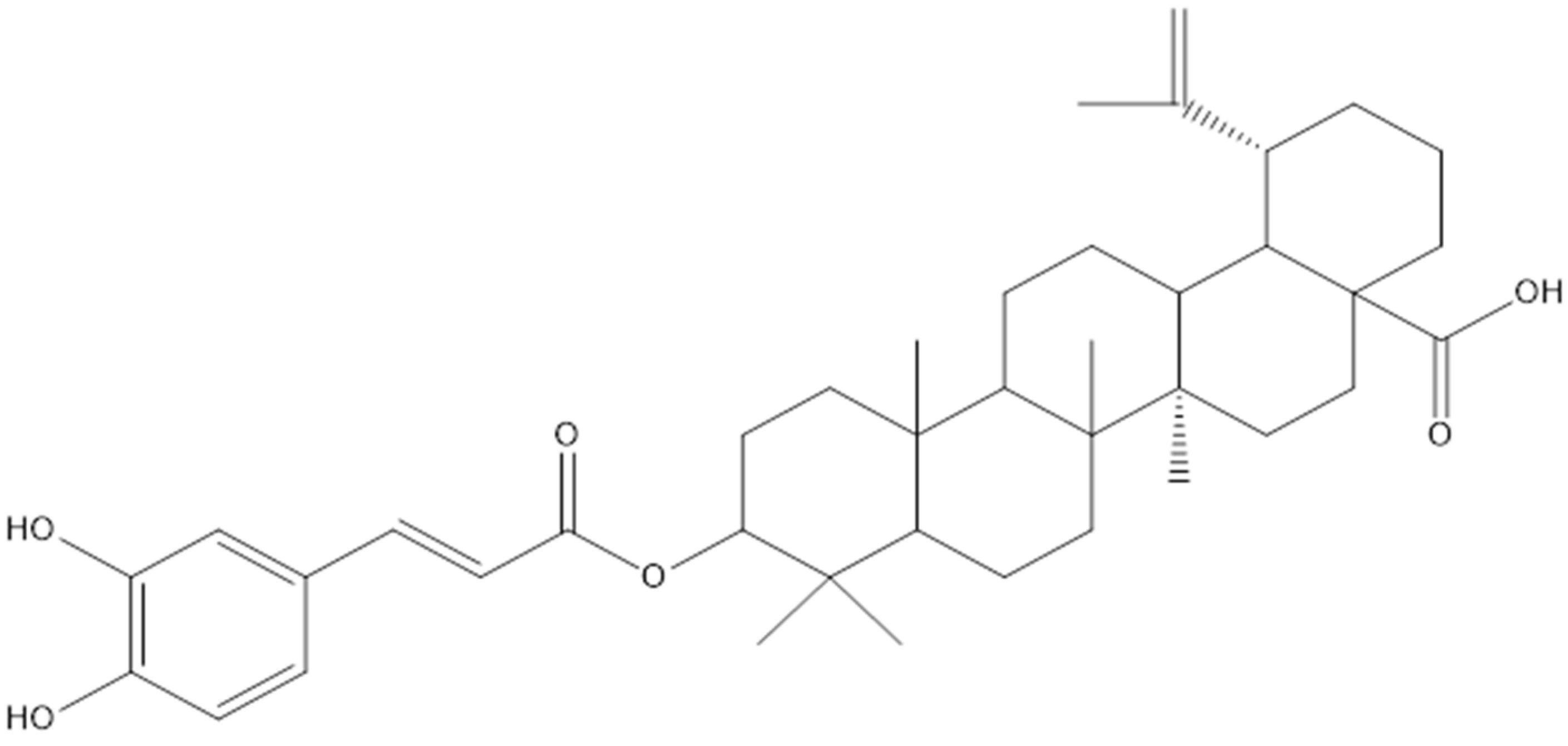

| [15] | Lupane | 28-O-acetyl-3 β-O-trans-caffeoylbetulin | L. senegalensis |

| 3-O-trans-caffeoylbetulin | L. senegalensis | ||

| 3-O-trans-caffeoylbetulinic acid | L. senegalensis | ||

| Betulin | L. senegalensis | ||

| Betulinic acid | L. senegalensis | ||

| Lupeol | L. senegalensis | ||

| 3-O-trans-caffeoyllupeol | L. senegalensis | ||

| Hopane | 3α-O-trans -p-coumaroyl-22-hydroxyhopane | L. senegalensis | |

| 3α-O-cis-p-coumaroyl-22-hydroxyhopane | L. senegalensis | ||

| 3α-O-trans-caffeoyl-22-hydroxyhopane | L. senegalensis | ||

| [19] | Other compounds | Mangiferin | L. fruticosa |

| 6-gingerol | L. fruticosa | ||

| Ellagic acid | L. fruticosa | ||

| Tannin | Procyanidin B2 | L. fruticosa | |

| Procyanidin B3 | L. fruticosa | ||

| Arecatannin A1 | L. fruticosa | ||

| Arecatannin A2 | L. fruticosa | ||

| 1,2,6-tri-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | L. fruticosa | ||

| [15] | 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone | L. senegalensis |

| Species | Plant Parts | Extract | Pharmacological Activities (In Vitro) | Pharmacological Activities (In Vivo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. alata (Blume) Leenh | Fruits (seed, flesh, and peel), leaves, bark | EtOH, MeOH, H2O | Antioxidant [5,29], Antimicrobial [5], Antihyperglycemic [27,30] Toxicity [29] | None |

| L. amoena (Hassk.) Leenh | Leaves, stem | EtOH, MeOH, N-hexane, and EtOAc | Antioxidant [21,31], Antimicrobial [31,32] | None |

| L. fruticosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Fruits | Chloroform, hexane, EtOAc, EtOH | Antioxidant [19], Antihyperglycemic [19] | None |

| L. senegalensis (Poir.) Leenh | Leaves, stems, roots | EtOH EtOAc, MeOH | Antimicrobial [17], Antimalarial [15], Toxicity [15,17] | None |

| L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Stem, leaves, bark | EtOH, MeOH | Antioxidant [28], Antimicrobial [33], Antimalarial [34] | Analgesic [28], Antidiarrheal [28], Antihyperglycemic [28] |

| L. tetraphylla (Vahl.) Radlk | Leaves | MeOH, AgNPs | Antimicrobial [35] | None |

| Ref | Species | Extraction | Part(s) Used | Antioxidant Test | Positive Controls | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | L. alata (Blume) Leenh | 60% Ethanol | Peel, flesh, seed | DPPH | BHT, vit. E, vit. C | The ethanolic extracts of seed (83.9%) and peel (83.2%) had significantly higher antioxidant activities than the flesh (52.4%) and controls except for vit. C (88.2%). |

| Peel, flesh, seed | ABTS | Trolox | The antioxidant activities of seed (48.2%) and peel (45.1%) were still the highest but significantly lower than the Trolox (64.7%). | |||

| [29] | Aqueous, methanol, and ethanol | Rind, flesh, seeds, whole fruits, leaves, and bark | DPPH | - | Ethanol and methanol extracts had higher DPPH radical scavenging activities compared to aqueous except for flesh. The ethanolic extracts of bark (93%) and seed (90%) had significantly higher antioxidant activities than the other parts. | |

| [21] | L. amoena (Hassk.) Leenh | Ethanol | Flesh, seed, pericarp | DPPH | Vit. C | The ethanolic extracts of the pericarp (IC50 53.21 ppm) and seed (IC50 63.31 ppm) had higher antioxidant activities than the flesh (IC50 122.51 ppm) but were lower compared to vit. C (IC50 3.06 ppm). |

| [31] | Methanol, 50% ethanol | Stem, leaves | DPPH | Catechin | All the extracts were unable to inhibit the oxidation reaction of DPPH by 50% with catechin used as a positive control. | |

| [19] | L. fruticosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and ethanol | Pulp and seed of unripe fruit | DPPH | BHT, vit. C, vit. E | DPPH scavenging activities: Seed extracts: (i) ethanol (IC50 0.178 mg/mL), ethyl acetate (IC50 5.351 mg/mL), chloroform (not detected), hexane (not detected). Pulp extracts: (i) ethanol (IC50 0.207 mg/mL), ethyl acetate (IC50 4.396 mg/mL), chloroform (IC50 13.613 mg/mL), hexane (IC50 29.151 mg/mL). Unripe ethanolic seed extract had stronger scavenging activity (IC50 0.178 mg/mL) than the ethanolic pulp extract (IC50 0.207 mg/mL), BHT (IC50 1.154 mg/mL), vit. C (IC50 0.087 mg/mL), and vit. E (IC50 0.210 mg/mL). |

| β-carotene bleaching assays | Vit. C | Β-carotene bleaching (%): Seed extracts: (i) ethanol (70%), ethyl acetate (40%), chloroform (−192%), hexane (−345%). Pulp extracts: (i) ethanol (49.5%), ethyl acetate (50.5%), chloroform (−3.8%), hexane (−290%). Ethanolic seed extract had the highest antioxidant activity (70%) compared to vit. C (25.8%). | ||||

| [28] | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Ethanol | Leaves | DPPH | Vit. C | Ethanolic leaf extracts had greater antioxidant activity (IC50 31.62 μg/mL) compared to the vit. C (IC50 12.02 μg/mL). |

| Ref | Species | Part/s Used | Study Design | Model | Extract | Positive Control | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | L. alata (Blume) Leenh | Fruits (seed, peel, and flesh) | Bacteria: B. subtilis, B. cereus, Listeria monocytogene, S. aureus, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa. | In vitro | 60% ethanol | Ampicillin, oxytetracycline, and chloramphenicol | The seed extract had the largest zone of inhibition against G +ve bacteria excluding L. monocytogenes and G −ve bacteria. |

| [32] | L. amoena (Hassk.) Leenh | Young, semi-mature, and mature leaves | Agar disc diffusion method. Bacteria: Propionibacterium acnes, Streptococcus mutans. Fungus: C. albicans. | In vitro | N-hexane, ethyl acetate, ethanol | - | Ethanolic extract of mature leaves’ antimicrobial activity had the highest inhibition zone against P. acnes (12.00 ± 0.00 mm) and C. albicans (16.11 ± 0.19 mm). |

| [31] | Stem and leaves | Antibacterial assay against Propionibacterium acnes. | Methanol, 50% ethanol | Chloramphenicol, tetracycline, isopropyl methylphenol | Stem: Methanol (MIC 1.0 mg/mL), 50% ethanol (MIC 1.0 mg/mL), (MBC 2.0 mg/mL). Chloramphenicol: MIC 0.13 mg/mL, MBC 0.13 mg/mL Tetracycline: MIC 0.03 mg/mL, MBC 0.03 mg/mL Isopropyl methylphenol: MIC 1.0 mg/mL, MBC 1.0 mg/mL | ||

| [33] | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Bark | Bacteria: B. cereus, S. aureus, Shigella dysenteriae, Salmonella typhi. Fungi: Aspergillus niger and C. albicans. | In vitro | Methanol | Cephradin, griseofulvin | A significant zone of inhibition was present in both G −ve bacteria but only in one G +ve bacteria (S. aureus). G +ve (B. cereus), had the maximum resistance. Minimal antifungal activity. |

| [17] | L. senegalensis (Poir.) Leenh | Leaf | Bacteria: S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, P. aeruginosa and E. coli. Fungi: A. fumigatus, C. neoformans and C. albicans. | In vitro | Ethanol | Gentamicin, amphotericin B | The antibacterial activity of the extract was greater than the positive control against both S. aureus and Enterococcus faecalis. Low antifungal activity in all three tested fungi. |

| [35] | L. tetraphylla (Vahl.) Radlk | Leaf | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing E. coli (ESBL E. coli), multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, and multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter species. | In vitro | Silver nanoparticles (AgNPS) synthesized using aqueous extract and methanol | Amikacin, piperacillin–tazobactam, polymyxin B | AgNPs significantly inhibited bacterial growth against multi-drug resistant S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter species, while crude methanolic leaf extract only inhibited the growth E. coli at different concentrations. |

| Ref | Species | Part(s) Used | Study Design | Model | Extract | Positive Control | Effect/Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | L. alata (Blume) Leenh | Mature leaf | α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity | In vitro | Aqueous | Acarbose | Aqueous extracts of mature leaves are 8.5 times more powerful than acarbose in inhibiting α-amylase. |

| [30] | Young and mature leaf | α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity | In vitro | Aqueous and its proanthocyanidis | Acarbose | Young leaves: Aqueous extracts 2.6 times and proanthocyanidins 5.3 times more potent than acarbose. Mature leaves: Aqueous extracts 8.5 times and proanthocyanidins 11.5 times more potent than acarbose. Inhibitory activities against starch hydrolase are age-dependent and increased as the leaves matured. | |

| [19] | L. fruticosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Seed, pulp | α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity | In vitro | Hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and ethanol | Acarbose | Ethanolic seed crude extracts of L. fruticosa had a significant inhibitory effect compared to acarbose, followed by pulp extract against α-glucosidase (p < 0.05). The maximum α-amylase inhibitory effect was observed in ethyl acetate seed extract followed by ethanolic pulp and ethyl acetate pulp. |

| [28] | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Leaf | Oral glucose solutions induced hyperglycemia in Swiss-albino mice | In vivo | Ethanol | +ve control: 5 mg/kg glibenclamide −ve control: 1% Tween-80 and water | Ethanolic extract (250 and 500 mg/kg BW) reduced blood glucose levels in a dose-dependent manner. |

| Ref | Pharmacological Activity | Species | Part (s) Used | Study design | Model | Extract | Positive control | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Antidiarrheal | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Leaf | Castor oil-induced diarrhea in Swiss-albino mice | In vivo | Ethanol | +ve control: loperamide 3 mg/kg −ve control: 1% Tween-80 and water | Ethanolic extract inhibits acute diarrhea in a dose-dependent manner. Percent of inhibition of defecation: (1) Loperamide group (88.59%) (2) Tested group 500 mg/kg BW extract (77.19%) (3) Tested group 250 mg/kg BW extract (57.89%) |

| [28] | Analgesic | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Leaf | Acetic acid writhing tests in Swiss-albino mice | In vivo | Ethanol | +ve control: Diclofenac-NA 25 mg/kg −ve control: 1% Tween-80 and water | Ethanolic extract inhibits writhing test in a dose-dependent manner. Percent of inhibition of writhing reflex: (1) Diclofenac-NA group (86.52%) (2) Tested group 500 mg/kg BW extract (58.43%) (3) Tested group 250 mg/kg BW extract (46.07%) |

| [15] | Antimalarial | L. senegalensis (Poir.) Leenh | Stems, roots | Parasites were subcultured in microtitration plates. The indicator of antimalarial activity was by calculating the inhibition of uptake of a radiolabeled nucleic acid precursor by the parasites | In vitro | Ethyl acetate isolated compounds | Mefloquine and dihydroartemisinin | Bioactive compound no. 6 (3-O-trans-caffeoylbetulinic) exhibited moderate antimalarial activity against P. falciparum (IC50 4.5 µM) |

| [34] | L. rubiginosa (Roxb.) Leenh | Stems | Measurement of HRP2 antimalarial assay was performed using ELISA against the P. falciparum 3D7 strain (chloroquine-sensitive) | In vitro | 80% Ethanol | Stem extract had the highest inhibition value (92.4%) at a concentration of 1000 µg/mL, but its IC50 value (IC50 252 µg/mL) was categorized as inactive. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarmizi, N.M.; Halim, S.A.S.A.; Hasain, Z.; Ramli, E.S.M.; Kamaruzzaman, M.A. Genus Lepisanthes: Unravelling Its Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101261

Tarmizi NM, Halim SASA, Hasain Z, Ramli ESM, Kamaruzzaman MA. Genus Lepisanthes: Unravelling Its Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals. 2022; 15(10):1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101261

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarmizi, Nadia Mohamed, Syarifah Aisyah Syed Abd Halim, Zubaidah Hasain, Elvy Suhana Mohd Ramli, and Mohd Amir Kamaruzzaman. 2022. "Genus Lepisanthes: Unravelling Its Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties" Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 10: 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101261

APA StyleTarmizi, N. M., Halim, S. A. S. A., Hasain, Z., Ramli, E. S. M., & Kamaruzzaman, M. A. (2022). Genus Lepisanthes: Unravelling Its Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties. Pharmaceuticals, 15(10), 1261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101261