Clinical Evidence of Magistral Preparations Based on Medicinal Cannabis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Search Eligibility Criteria

4.2. Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bridgeman, M.; Abazia, D. Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, And Implications for the Acute Care Setting. PT 2017, 42, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Galicia, P.B.D.; González-González, A.; Romo-Parra, H. Breve historia sobre la marihuana en Occidente. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 67, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, D.I. The therapeutic effects of Cannabis and cannabinoids: An update from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 49, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. In The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, P.F.; Wolff, R.F.; Deshpande, S.; Di Nisio, M.; Duffy, S.; Hernandez, A.V.; Keurentjes, J.C.; Lang, S.; Misso, K.; Ryder, S.; et al. Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 2456–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, M.; Ashton, J.C. What is medicinal cannabis? N. Z. Med. J. 2019, 132, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nice Guideline Updates Team. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. In Cannabis-Based Medicinal Products; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fraguas-Sánchez, A.I.; Torres-Suárez, A.I. Medical Use of Cannabinoids. Drugs 2018, 78, 1665–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiani, B.; Sarhadi, K.J.; Soula, M.; Zafar, A.; Quadri, S.A. Current application of cannabidiol (CBD) in the management and treatment of neurological disorders. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 3085–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USP 41-NF 36. <795> Pharmaceutical Compounding—Nonsterile Preparations US Pharmacopoeia, 41th ed. 2019. Available online: https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/our-work/compounding/usp-gc-795-proposed-revision.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- European Pharmacopoeia. Pharmaceutical Preparations European Pharmacopoeia, 7th ed.; European Pharmacopoeia Commission: Strasbourg, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Decreto 613 de 2017; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Citti, C.; Battisti, U.M.; Braghiroli, D.; Ciccarella, G.; Schmid, M.; Vandelli, M.A.; Cannazza, G. A Metabolomic Approach Applied to a Liquid Chromatography Coupled to High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method (HPLC-ESI-HRMS/MS): Towards the Comprehensive Evaluation of the Chemical Composition of Cannabis Medicinal Extracts. Phytochem. Anal. PCA 2018, 29, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcieri, C.; Tomasello, C.; Simiele, M.; De Nicolò, A.; Avataneo, V.; Canzoneri, L.; Cusato, J.; Di Perri, G.; D’Avolio, A. Cannabinoids concentration variability in cannabis olive oil galenic preparations. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Procedimiento de Formulación Magistral. Buenas Prácticas en Farmacia Comunitaria en España; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, L.J.; Handlos, V.; Walser, S.; Schutjens, M.H.; Neef, C. Legislation on the preparation of medicinal products in European pharmacies and the Council of Europe Resolution. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 24, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granda, E. Formulación magistral. Farm. Prof. 2004, 18, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.F.; Pollard, G.T. Preparation and Distribution of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Dosage Formulations for Investigational and Therapeutic Use in the United States. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urits, I.; Borchart, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Kochanski, J.; Orhurhu, V.; Viswanath, O. An Update of Current Cannabis-Based Pharmaceuticals in Pain Medicine. Pain Ther. 2019, 8, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaneto, M.S.; Gorelick, D.A.; Desrosiers, N.A.; Hartman, R.L.; Pirard, S.; Huestis, M.A. Synthetic cannabinoids: Epidemiology, pharmacodynamics, and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014, 144, 12–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Resolución 1478 de 2006; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2006.

- Congreso de la Republica de Colombia. Decreto 677 de 2015; Congreso de la Republica de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015.

- Congreso de la Republica de Colombia. Ley 1787 de 2016; Congreso de la Republica de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Resolución 2892 de 2017; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Resolución 315 de 2020; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- Grotenhermen, F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, C.A.; Russo, E.B. Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 49, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.P. Medical Marijuana for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Other Medical and Psychiatric Problems: A Clinical Review. JAMA 2015, 313, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, V.; Makriyannis, A. Medicinal Chemistry of Cannabinoids. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 97, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.A.; Tichkule, R.; Bajaj, S.; Makriyannis, A. Latest advances in cannabinoid receptor agonists. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009, 19, 1647–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, C.S.; Conroy, M.; Vanden Heuvel, B.D.; Park, S.H. Cannabidiol Drugs Clinical Trial Outcomes and Adverse Effects. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, S.; Mammana, S.; Cavalli, E.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. Use of Cannabidiol in the Treatment of Epilepsy: Efficacy and Security in Clinical Trials. Molecules 2019, 24, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutge, E.E.; Gray, A.; Siegfried, N. The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerleider, J.; Sarna, G.; Fairbanks, L.; Goodnight, J.; Andrysiak, T.; Jamison, K. THC or Compazine for the cancer chemotherapy patient—The UCLA study. Part II: Patient drug preference. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1985, 8, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, L.; McKernan, J. Antiemetic Effect of d-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol in Chemotherapy-Associated nausea and Emesis As Compared to Placebo and Compazin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1981, 21, 76S–80S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frytak, S.; Moertel, C.; O’Fallon, J.; Rubin, J.; Creagan, E.; O’Connell, M. Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol as an Antiemetic for Patients Receiving Cancer Chemotherapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1981, 91, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, L.M.; Lampert, S.L.; Ewigman, B. Barriers to Achieving Optimal Success with Medical Cannabis: Opportunities for Quality Improvement. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, P.; Pichini, S.; Pacifici, R.; Busardo, F.P.; Del Rio, A. Herbal Preparations of Medical Cannabis: A Vademecum for Prescribing Doctors. Medicina 2020, 56, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Cannabis and the Cannabinoids; Health Canada: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2018.

- Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, D.; O’Neill, J.; Waters, E.; White, H.; PRISMA-Equity Bellagio Group. PRISMA-Equity 2012 extension: Reporting guidelines for systematic reviews with a focus on health equity. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Pharmacokinetics | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Absorption | The main forms of administration and formulations are:

|

| Distribution |

|

| Metabolism |

|

| Elimination | It is eliminated unchanged and as a metabolite in urine (16%) and feces with an average of t ½ of 24 h [28]. |

| Magistral Preparations with Main Component of THC | Magistral Preparations with Main Component of CBD |

|---|---|

|

|

| Study Type | Objective | Type of Magistral Preparations Used and Comparator | n | Outcome | Adverse Event | Conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

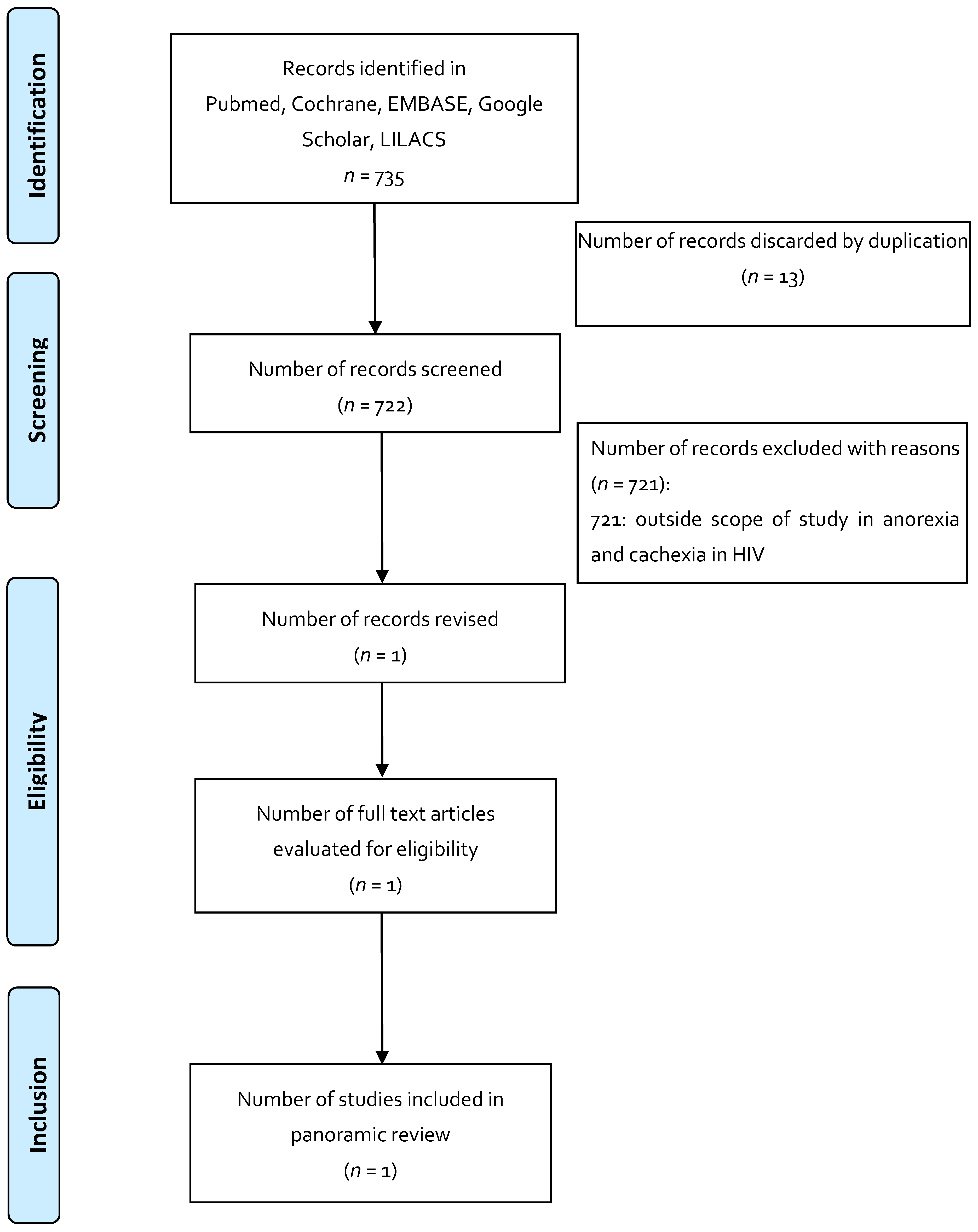

| Indication 1: Anorexia and cachexia in HIV | |||||||

| Systematic Review | To assess whether cannabis (in its natural or artificial form), whether smoked or ingested, reduces morbidity or mortality in HIV-infected patients. | Cannabis smoked or ingested, THC ingested (dronabinol or any form produced). Compared to placebo, no medication, another form of cannabis. | 7 studies | Primary: Mortality (HIV-related, all causes) Secondary: Subjective and objective appetite experiences: 1. Cannabis vs placebo: Weight gain. Study number: 1, participants 88 OR (95% CI) 2.40 [0.70, 8.23] 2. Changes in appetite, food, and calorie intake: insufficient data do not allow for analysis of this measure. | 1 study: 1 subject discontinued the study for psychosis; 2 study: 2 discontinued the study due to sedation and changes in mood. | Evidence on the efficacy and safety of cannabis and cannabinoids is lacking; most of the studies that were analyzed were of short duration, with a small number of patients, and focused on short-term efficacy measures; one of the most important limitations is not having long-term safety data. | [36] |

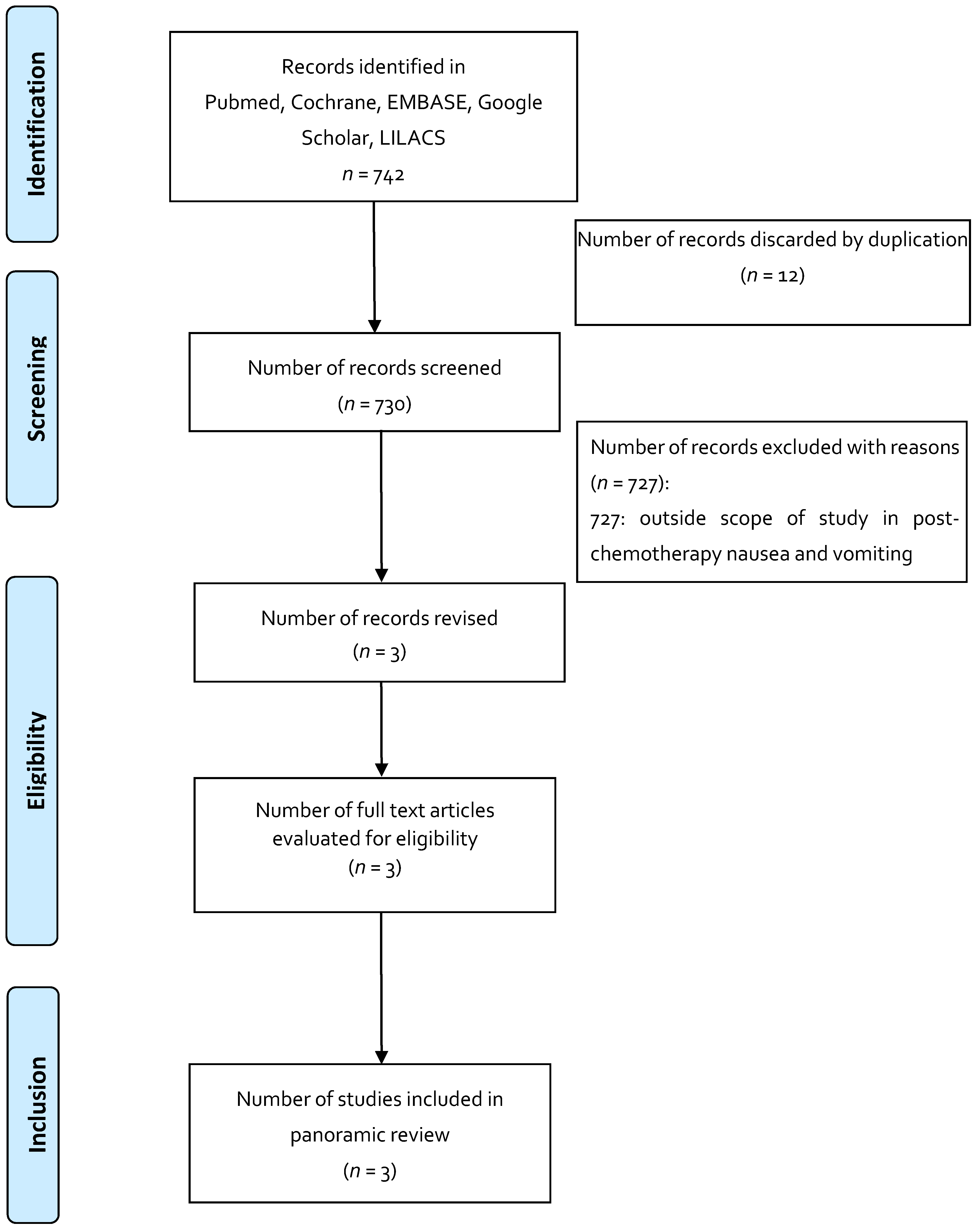

| Indication 2: Post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting | |||||||

| RCT crossover | To determine formulation preference for THC vs Compazine. | THC (offered by NIDA and administered per body surface area as follows: 7.5 mg for 1.4 m2, 10 mg for 1.4–1.8 m2, 12.4 mg for >1.8 m2 vs. Compazine (10 mg prochlorperazine dose). | 139 (variety of neoplasms and different QT regimens) | Reported preference: 49% for THC, 43% for Compazine, 8% no preference. Nausea reduction: There was a reduction in both groups. | Sedation and psychoactive effects were greater in the THC group. | The preference for THC was associated with more adverse events related to the magisterial preparation compared to Compazine. Most studies with THC exclude patients with emotional instability; however, it is a condition that is associated with cancer and that can interfere with the proper use of THC. | [37] |

| RCT, double blind, randomized, crossover | To determine the degree of effectiveness of the oral THC formula in preventing nausea and vomiting associated with QT compared with the conventional antiemetic and placebo. | Oral THC at 7 mg/m2 every 4 h for 4 doses (NIDA), administered in 0.12 mL of sesame oil and supplied in gelatinous capsules; oral prochlorperazine at 7 mg/m2 every 4 h for 4 doses and placebo (administered 1 h prior to QT). | 55 | Absence of nausea in 40 of 55 patients receiving THC, 8 of 55 receiving prochlorperazine, and 5 of 55 receiving placebo. | THC group AEs were euphoria, sedation, and temporary loss of physical control; AEs in the chlorperazine group were excessive sleepiness and autonomic symptoms. | It concludes that the magistral preparations with THC seem to be more effective in controlling vomiting associated with cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, and doxorubicin, and less for nitrogen mustards and nitrosurea. | [38] |

| RCT, double blind, randomized, crossover | To observe the effect of THC as an antiemetic agent in cancer patients and to compare the antiemetic and AE effect of THC with those using prochlorpromazine. | THC: 15 mg orally 3 times per day vs. prochlorperazine 10 mg orally 3 times per day or placebo. | 116 | Occurrence of no nausea and vomiting events on days 2–4 (mild emetic stimulus): THC (57), prochlorperazine (72), placebo (53). | Greater degree of intolerable sedation in the THC group (5) vs. chlorperazine (2). 12 patients from the THC group (1 from pbo, 1 from chlorperazine) discontinued the study due to central intolerable symptoms. | Concludes that the THC-rich magistral preparations had superior antiemetic activity compared to placebo, but had no advantages compared to prochlorperazine. Adverse events related to the central nervous system were more frequent and severe with THC, with the dose and scheme used in the elderly population; additionally, the use of the formula rich in THC resulted in unpleasant experiences compared to prochlorperazine and placebo. Describes that the formula used shows that it prevents post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting, yet its role must be clarified before it is recommended for general use. | [39] |

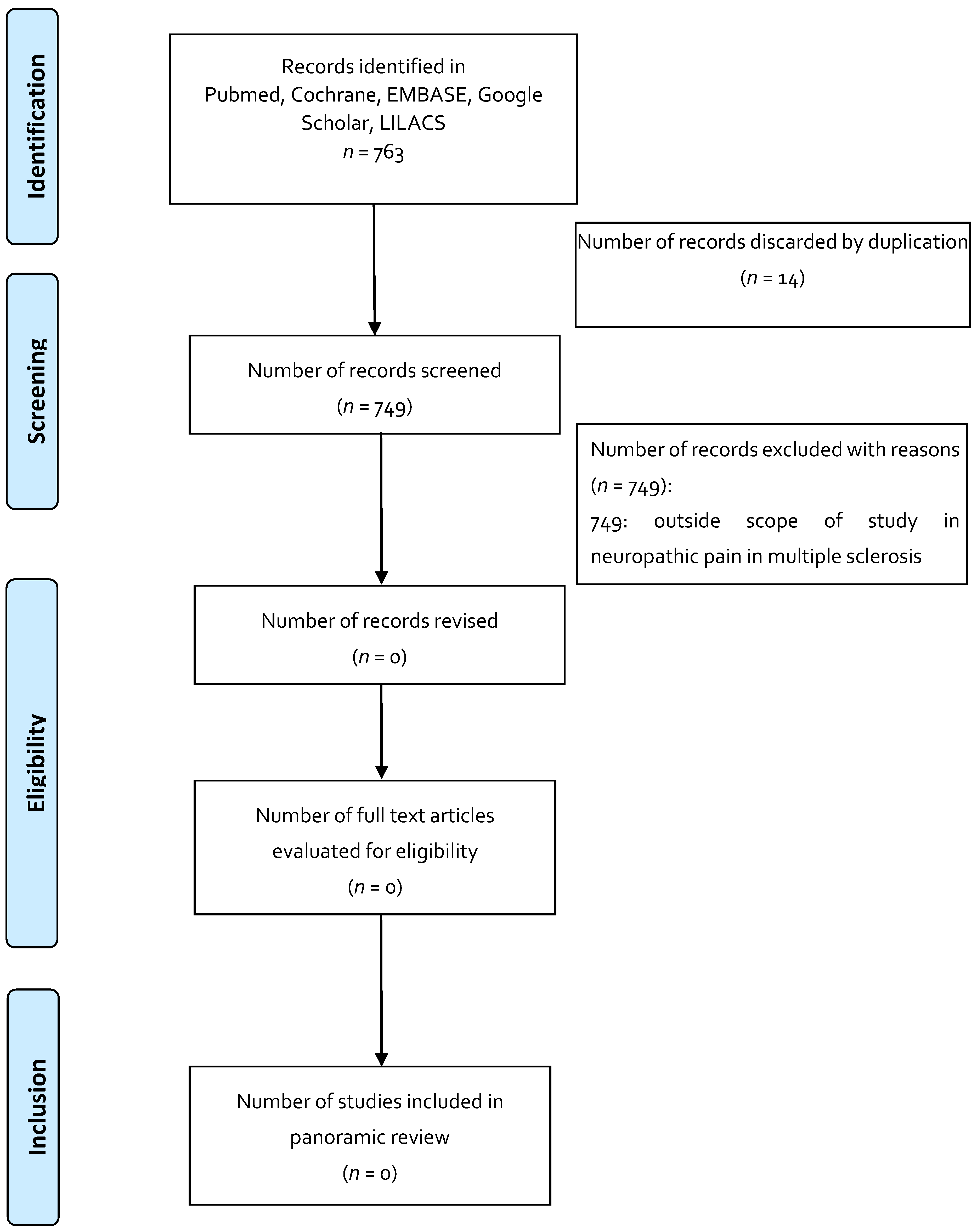

| Indication 3: Neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis | |||||||

| None | |||||||

| TERMS | MeSH | DeSC |

|---|---|---|

| Anorexia and cachexia in HIV | Anorexia AND HIV | anorexia AND HIV |

| Medicinal cannabis | Medical Marijuana | medical cannabis |

| Magistral preparations | Pharmaceutical Preparations | pharmaceutical preparations |

| Post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting | Nausea AND Vomiting AND Chemotherapy | Nausea AND Vomiting AND Chemotherapy |

| Neuropathic pain in patients with multiple sclerosis | Chronic Pain OR Multiple Sclerosis | Chronic Pain OR Multiple Sclerosis |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias, S.; Leon, M.; Jaimes, D.; Bustos, R.-H. Clinical Evidence of Magistral Preparations Based on Medicinal Cannabis. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020078

Arias S, Leon M, Jaimes D, Bustos R-H. Clinical Evidence of Magistral Preparations Based on Medicinal Cannabis. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(2):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020078

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias, Sara, Marta Leon, Diego Jaimes, and Rosa-Helena Bustos. 2021. "Clinical Evidence of Magistral Preparations Based on Medicinal Cannabis" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 2: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020078

APA StyleArias, S., Leon, M., Jaimes, D., & Bustos, R.-H. (2021). Clinical Evidence of Magistral Preparations Based on Medicinal Cannabis. Pharmaceuticals, 14(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020078