VitalSign6: A Primary Care First (PCP-First) Model for Universal Screening and Measurement-Based Care for Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. What Is the Problem?

3. How Is This Problem Being Addressed?

4. How Have These Efforts Fared?

5. An Alternative Approach

- Recognition of depression through universal screening.

- Diagnosis of depression using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.

- Selection of appropriate treatment (active surveillance, brief therapy, medication management) based on more accurate clinical evaluation.

- Tailored medication delivery using Measurement-Based Care (e.g., optimized, algorithm-based dosing with decision support/consultation, based on regular, systematic assessment of symptoms, side-effects, and adherence).

- Continuation/maintenance phase treatment.

- System-level monitoring of adherence to evidence-based treatment recommendations/guidelines via feedback to clinicians (i.e., clinical decision support, rounds with consulting clinicians, patient navigation) at the point of care.

6. Incorporating Health IT Advances into Depression Care

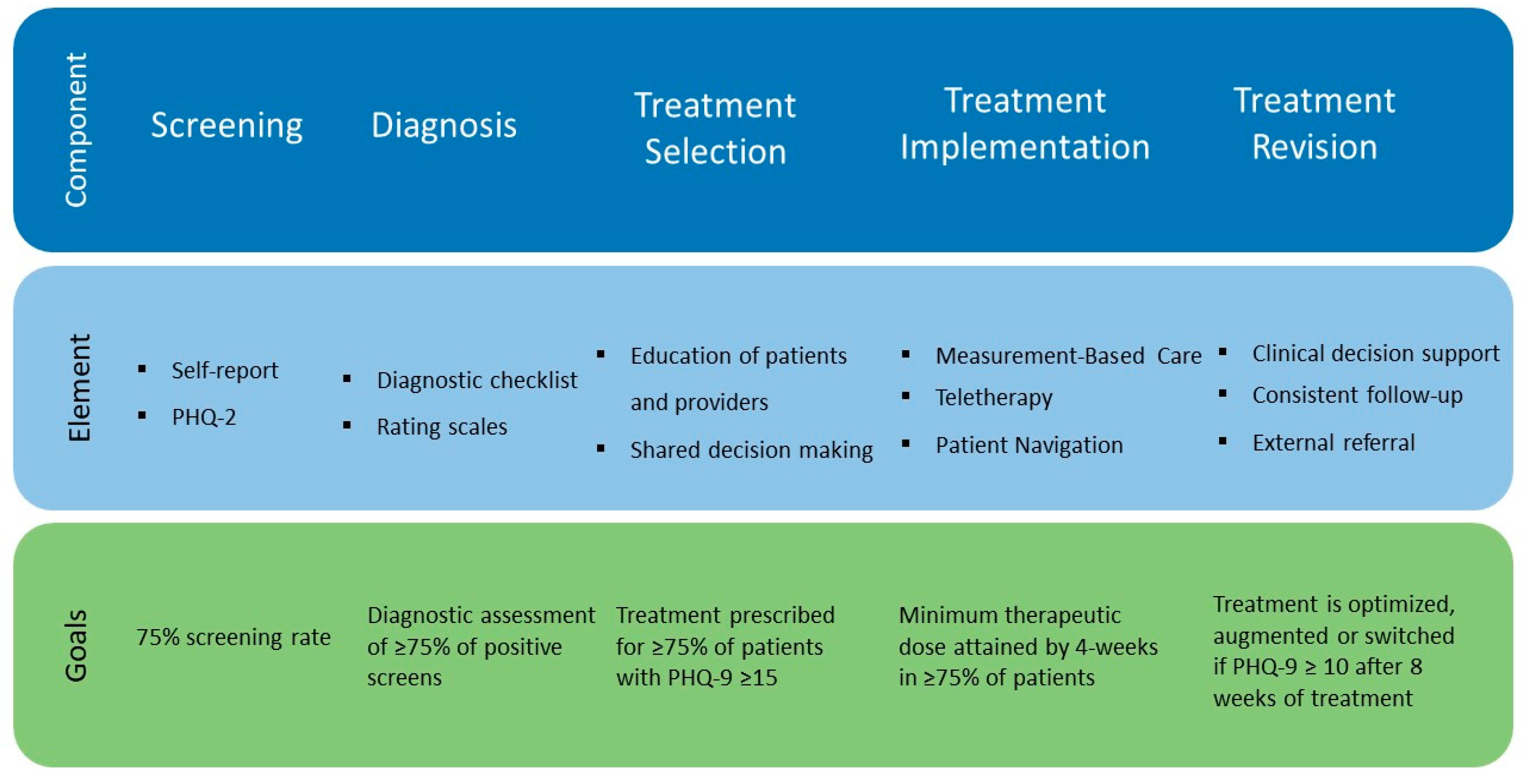

7. Operationalizing Our Approach: Making Screening for Depression the Sixth Vital Sign

- Routinely and consistently identify patients suffering from depression using self-report assessments.

- Accurately diagnose and adequately manage patients who screen positive on self-report assessments.

- Improve long-term outcomes for depressed patients as compared to historical controls.

- Screening

- Diagnosis

- Treatment Selection

- Treatment Implementation

- Treatment Revision

8. Methods

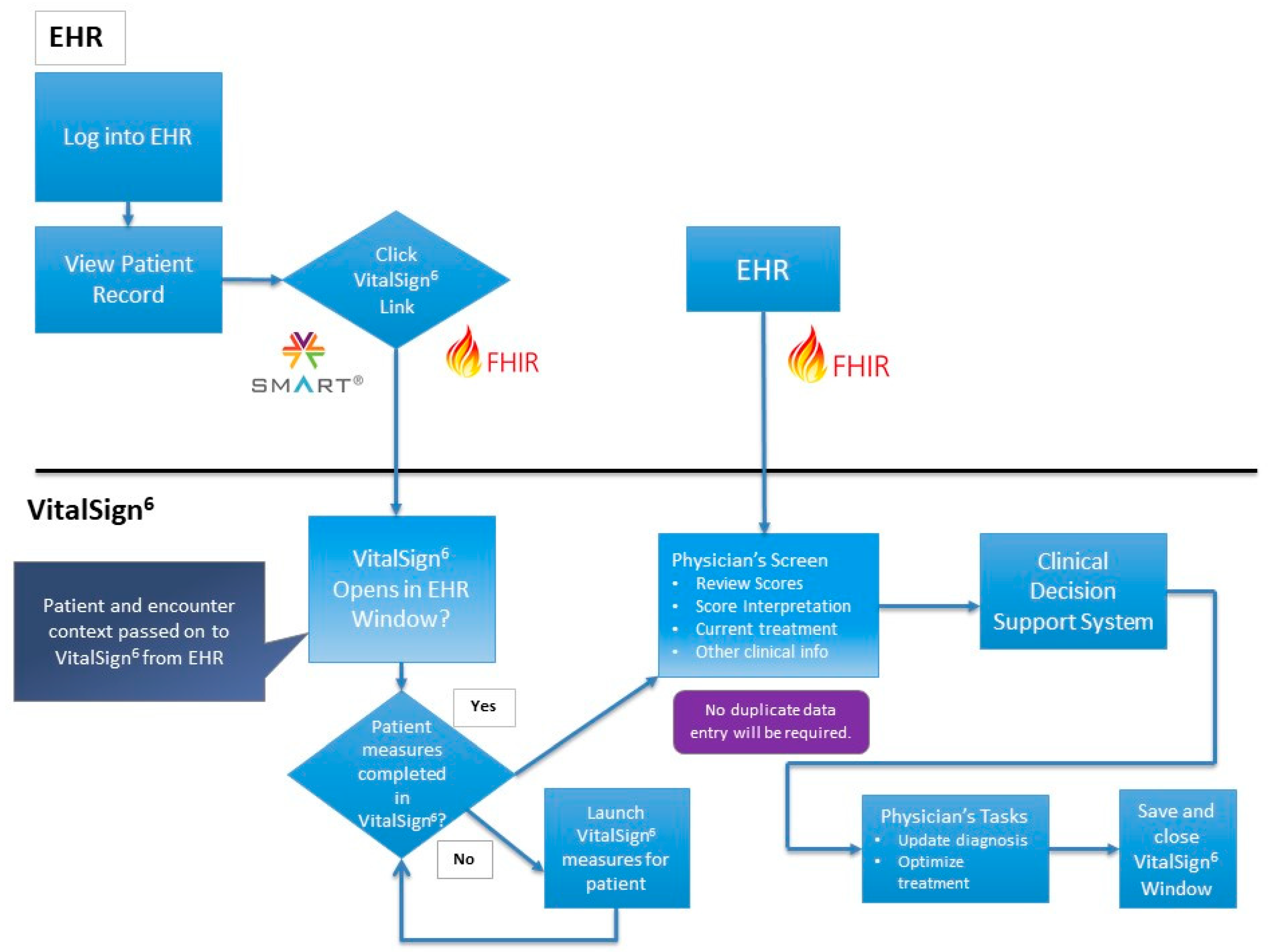

8.1. VitalSign6 Software

8.2. Patient Health Record

8.3. Electronic Health Record and Interoperability

8.4. Remote Patient Assessment

8.5. Selection of Collaborating Clinics

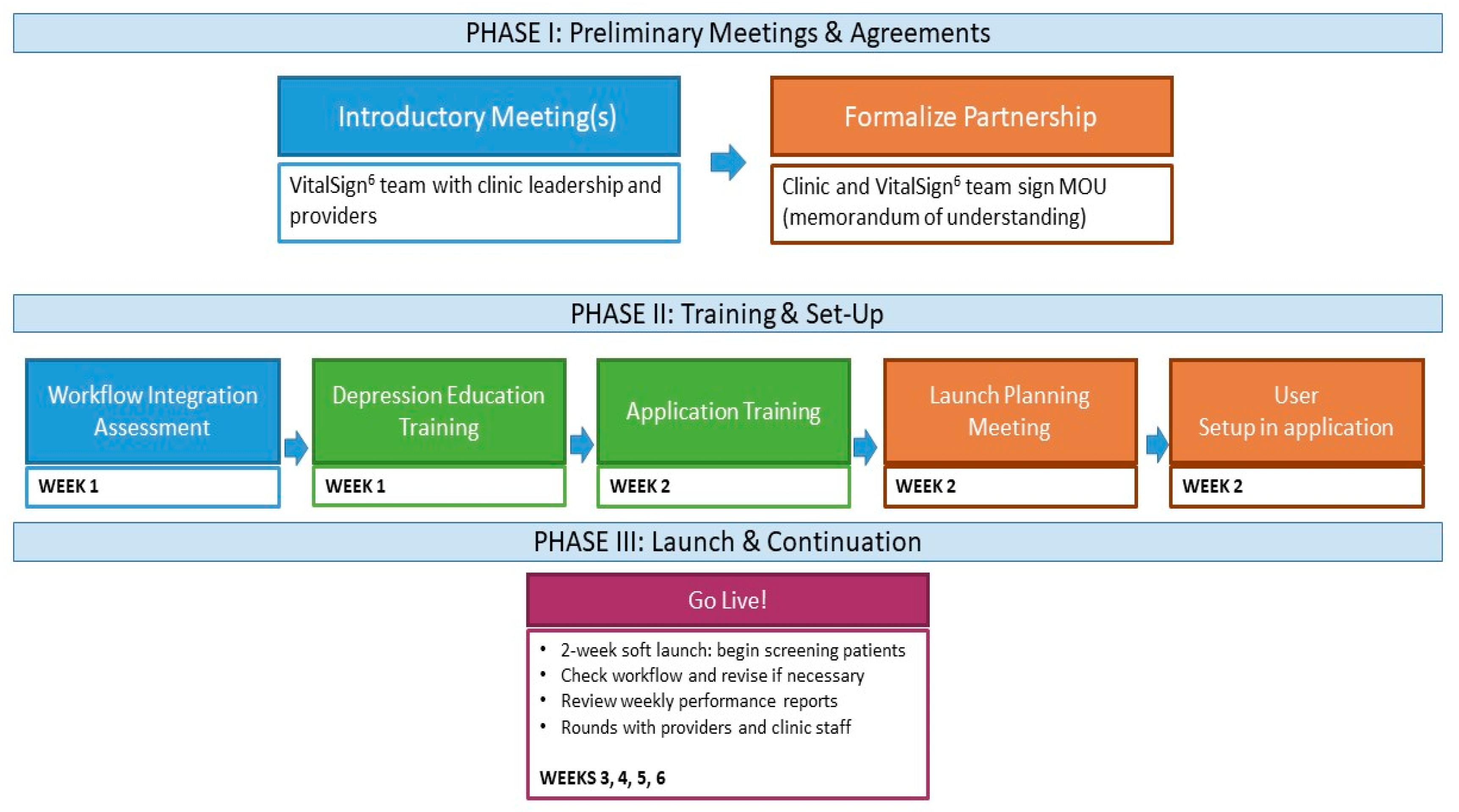

8.6. Implementation of VitalSign6

- Workflow integration assessment, which allows the project team to customize implementation, based on clinical operations information (number of providers and exam rooms, flow of patients through the clinic, as well as existing practices for management of chronic illnesses).

- Depression education and application training for all clinic staff, via in-person and online modules, including an overview of depression and introduction to MBC.

- Launch planning, including finalization of workflow and set-up of individual profiles in the VS6 software application.

- Initiation of screening and MBC implementation with a “Soft Launch”. During the initial 2-week period, a member of the VitalSign6 team is onsite at the clinic, reviewing training material with clinic staff, facilitating incorporation of depression screening into the clinic’s workflow, and ensuring that all clinic staff are comfortable using the VS6 application and administering the screening. For those patients who screen positive, clinicians are instructed on how to conduct a clinical interview and document the follow-up plan. During this period and beyond, a consulting psychologist/psychiatrist on the VitalSign6 team is available to coach the clinicians on how to manage their depressed patients.

8.7. Operationalization of VitalSign6 Components

- Screening—The initial screening for all patients is conducted through the VS6 software, with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2), which assesses the two core symptoms of major depression (sad mood and anhedonia) with items scored from 0–3 (PHQ-2 range: 0–6) [44]. A positive screen on the PHQ-2 is defined as a total score greater than 2 [44]. For those who screen positive on the PHQ-2, VS6 immediately generates the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which assesses for symptoms in all nine domains of a major depressive episode [45]. The standard package of additional assessments that patients receive with a positive PHQ-2 screen include (1) 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale, which assesses for symptoms in seven domains of generalized anxiety disorder [52]; (2) 5-item Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM), which assesses for symptoms of mania [53]; (3) 2-item Physical Activity Questionnaire, which assesses patient’s level of physical activity [54]; (4) 4-item Pain Frequency, Intensity, and Burden Scale (P-FIBS), a brief, self-administered measurement of pain frequency, intensity, and burden [55]; (5) single-item screening question each for alcohol and drug use disorders [56,57], each designed to screen for current usage patterns that might impact depression treatment; (6) 6-item Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI), which assesses to what extent the patient’s depressive symptoms impacted his/her work attendance and productivity [58]; and (7) the 16-item Concise Associated Symptoms Tracking—Self-Report Scale (CAST-SR), which assesses for the five known treatment-emergent symptom domains: Irritability, anxiety, mania, insomnia, and panic [59,60]. For those with a negative PHQ-2 screen, no further assessment is mandated. As soon as a patient completes her/his assessment, the results are immediately available for review by the clinician.

- Diagnosis—Clinicians have the option to administer optional self-report assessments, available within VS6, to collect additional information needed to conduct a thorough diagnostic assessment. For example, in patients with positive PHQ-2 screen, their response to the 9th item of PHQ-9 (“Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way”) is flagged for clinicians. Clinicians have the option to administer additional validated instruments for detailed suicide risk assessments, including the Concise Health Risk Tracking (CHRT) scale [61], which has been validated in diverse groups of patients with psychiatric disorders [62,63,64]. Additionally, clinicians are trained on identifying the risk factors for suicide and on utilizing appropriate triage pathways based on the resources available. Such an approach is consistent with recommendations for depression screening in other medical settings, such as in patients with cardiovascular disease [65]. Also, for patients who screened positive for alcohol or drug use, providers may wish to administer the 28-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) [66] or the 24-item Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) [67]. Clinical providers can then utilize the Major Depression Diagnostic Checklist based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th edition (DSM-5), available within VS6 on the follow-up plan page, to confirm or rule out a diagnosis [68]. Clinicians also have the option to conduct additional follow-up visit(s) to ensure accurate diagnosis.

- Treatment Selection—The treatment plan options available to providers include: (1) pharmacological treatment implemented with MBC; (2) active surveillance by the primary care clinician with symptomatic monitoring; (3) behavioral treatment, such as psychotherapy, in primary care setting, through integrated behavioral health providers; (4) exercise; (5) referral to an external provider for specialty care; or (6) no further follow-up. Additionally, clinicians could indicate whether the patient refused the prescribed treatment option. Primary care clinicians are predominantly trained on pharmacotherapy for depression. However, training, as well as referral resources for other evidence-based treatment for depression, such as psychotherapy and exercise, are readily available.

- Treatment Implementation—The adherence of depressed patients to prescribed antidepressant treatment is measured using the Patient Adherence Questionnaire (PAQ) [69], which is a two-item self-report instrument administered via VS6. Patients who do not take their prescribed medications more than 70% of the time are considered non-adherent. For these patients, the instrument asks them to select the reasons for their non-adherence and these reasons are monitored by the prescribing clinicians. Prescribing clinicians also monitor medication side-effects, using the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating (FIBSER) scale [70], which is a three-item, self-report instrument that assesses the frequency, intensity, and functional impairment, or burden, of reported side effects. The VS6 application scores the measures and reports the results to the provider. Based on the score, the side effects are categorized as acceptable, requiring attention, or unacceptable.

- Treatment Revision—VitalSign6 provides electronic clinical decision support for Measurement-Based Care treatment of depression at the point of care. It facilitates the delivery of personalized care, by using data from self-report measures, completed by the patient during the visit before being seen by the provider. VitalSign6 sends all of the relevant data points to its sophisticated logics engine which contains all the intelligence of the best practice treatment algorithms for treatment of depression. The logics engine uses the patient’s individual measures data to calculate the most appropriate treatment recommendation specific to the current point of care.

9. Metrics of Success

10. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 743–800. [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Naghavi, M.; Lozano, R.; Michaud, C.; Ezzati, M.; Shibuya, K.; Salomon, J.A.; Abdalla, S.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2163–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Goodwin, R.D.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P.S. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Jama 2003, 289, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, D.S.; Sarvet, A.L.; Meyers, J.L.; Saha, T.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Stohl, M.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignone, M.; Gaynes, B.N.; Rushton, J.L.; Mulrow, C.D.; Orleans, C.T.; Whitener, B.L.; Mills, C.; Lohr, K.N. US Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, Formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Screening for Depression; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2002.

- Coyne, J.C.; Schwenk, T.L.; Fechner-Bates, S. Nondetection of depression by primary care physicians reconsidered. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1995, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.S.; Berglund, P.; Olfson, M.; Pincus, H.A.; Wells, K.B.; Kessler, R.C. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Klap, R.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Wells, K.B. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the united states. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.; Bush, T.; Ormel, J. Adequacy and Duration of Antidepressant Treatment in Primary Care. Med. Care 1992, 30, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampallona, S.; Bollini, P.; Tibaldi, G.; Kupelnick, B.; Munizza, C. Patient adherence in the treatment of depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warden, D.; Trivedi, M.H.; WHowland, R.; Fava, M. Predictors of Attrition During Initial (Citalopram) Treatment for Depression: A STAR*D Report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pence, B.W.; O’Donnell, J.K.; Isniewski, S.R.; Davis, L.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Gaynes, B.N.; Zisook, S.; Hollon, S.D.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Gaynes, B.N. The depression treatment cascade in primary care: A public health perspective. Curr. Psychiatry. Rep. 2012, 14, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. 2012. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2012_namcs_web_tables.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2016.).

- Davis, K.A.; Sudlow, C.L.; Hotopf, M. Can mental health diagnoses in administrative data be used for research? A systematic review of the accuracy of routinely collected diagnoses. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Motulsky, A.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Eguale, T.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Tamblyn, R. Off-label indications for antidepressants in primary care: Descriptive study of prescriptions from an indication based electronic prescribing system. BMJ 2017, 356, j603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruickshank, G.; Macgillivray, S.; Bruce, D.; Mather, A.; Matthews, K.; Williams, B. Cross-sectional survey of patients in receipt of long-term repeat prescriptions for antidepressant drugs in primary care. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2008, 5, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hiance-Delahaye, A.; de Schongor, F.M.; Lechowski, L.; Teillet, L.; Arvieu, J.J.; Robine, J.M.; Ankri, J.; Herr, M. Potentially inappropriate prescription of antidepressants in old people: Characteristics, associated factors, and impact on mortality. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A.L.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Grossman, D.C.; Baumann, L.C.; Davidson, K.W.; Ebell, M.; Garcia, F.A.; Gillman, M.; Herzstein, J.; Kemper, A.R.; et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama 2016, 315, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.A.; Whitlock, E.P.; Gaynes, B.; Beil, T.L. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, Formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Screening for Depression in Adults and Older Adults in Primary Care: An Updated Systematic Review; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2009.

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Screening for Depression in Adults (CAG-00425N). Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=251 (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Flanagan, T.; Avalos, L.A. Perinatal Obstetric Office Depression Screening and Treatment: Implementation in a Health Care System. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.C.; Ellis, A.R.; Konrad, T.R.; Holzer, C.E.; Morrissey, J.P. County-Level Estimates of Mental Health Professional Shortage in the United States. Psychiatry Serv. 2009, 60, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unützer, J.; Katon, W.; Callahan, C.M.; Williams, J.W., Jr.; Hunkeler, E.; Harpole, L.; Hoffing, M.; Della Penna, R.D.; Noël, P.H.; Lin, E.H.; et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Jama 2002, 288, 2836–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katon, W.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.; Walker, E.; Simon, G.E.; Bush, T.; Robinson, P.; Russo, J. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. Jama 1995, 273, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Robinson, P.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.; Bush, T.; Ludman, E.; Simon, G.; Walker, E. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergus, G.R.; Hartz, A.J.; Noyes, R.; Ward, M.M., Jr.; James, P.A.; Vaughn, T.; Kelley, P.L.; Sinift, S.D.; Bentler, S.; Tilman, E. The limited effect of screening for depressive symptoms with the PHQ-9 in rural family practices. J. Rural Health 2005, 21, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensichen, J.; von Korff, M.; Peitz, M.; Muth, C.; Beyer, M.; Guthlin, C.; Torge, M.; Petersen, J.J.; Rosemann, T.; König, J.; et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: A cluster randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, D.A.; Bungay, K.M.; Wilson, I.B.; Pei, Y.; Supran, S.; Peckham, E.; Cynn, D.J.; Rogers, W.H. The impact of a pharmacist intervention on 6-month outcomes in depressed primary care patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivin, K.; Pfeiffer, P.N.; Szymanski, B.R.; Valenstein, M.; Post, E.P.; Miller, E.M.; McCarthy, J.F. Initiation of Primary Care-Mental Health Integration programs in the VA Health System: Associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Med. Care 2010, 48, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Zivin, K.; Szymanski, B.R.; Pfeiffer, P.N.; McCarthy, J.F. VA primary care-mental health integration: Patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services, 2008–2010. Psychiatry Serv. 2012, 63, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, B.R.; Bohnert, K.M.; Zivin, K.; McCarthy, J.F. Integrated care: Treatment initiation following positive depression screens. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bohnert, K.M.; Pfeiffer, P.N.; Szymanski, B.R.; McCarthy, J.F. Continuation of care following an initial primary care visit with a mental health diagnosis: Differences by receipt of VHA Primary Care-Mental Health Integration services. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.A.; Hill, J.J.; Gask, L.; Lovell, K.; Chew-Graham, C.; Bower, P.; Cape, J.; Pilling, S.; Araya, R.; Kessler, D.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013, 347, f4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J.; Bower, P.; Gilbody, S.; Lovell, K.; Richards, D.; Gask, L.; Dickens, C.; Coventry, P. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 10, Cd006525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, L.I.; Crain, A.L.; Maciosek, M.V.; Unutzer, J.; Ohnsorg, K.A.; Beck, A.; Rubenstein, L.; Whitebird, R.R.; Rossom, R.C.; Pietruszewski, P.B.; et al. A stepped-wedge evaluation of an initiative to spread the collaborative care model for depression in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crismon, M.L.; Trivedi, M.; Pigott, T.A.; Rush, A.J.; Hirschfeld, R.M.; Kahn, D.A.; DeBattista, C.; Nelson, J.C.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Sackeim, H.A.; et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: Report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1999, 60, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Crismon, M.L.; Kashner, T.M.; Toprac, M.G.; Carmody, T.J.; Key, T.; Biggs, M.M.; Shores-Wilson, K.; Witte, B.; et al. Clinical results for patients with major depressive disorder in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Xiang, Y.T.; Xiao, L.; Hu, C.Q.; Chiu, H.F.; Ungvari, G.S.; Correll, C.U.; Lai, K.Y.; Feng, L.; Geng, Y.; et al. Measurement-Based Care Versus Standard Care for Major Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial With Blind Raters. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Warden, D.; Ritz, L.; Norquist, G.; Howland, R.H.; Lebowitz, B.; McGrath, P.J.; et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynes, B.N.; Warden, D.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Fava, M.; Rush, A.J. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatry Serv. 2009, 60, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, P. Congressional intent for the HITECH Act. Am. J. Manag. Care 2010, 16, Sp24-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brailer, D.J. Perspective: Presidential leadership and health information technology. Health Aff. 2009, 28, w392–w398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Milstein, J.; DesRoches, C.M.; Furukawa, M.F.; Worzala, C.; Charles, D.; Kralovec, P.; Stalley, S.; Jha, A.K. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 1664–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halamka, J.D.; Mandl, K.D.; Tang, P.C. Early experiences with personal health records. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2008, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protection, P.; Act, A.C. Patient protection and affordable care act. Public Law 2010, 111, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Callaly, T.; Hallebone, E.L. Introducing the routine use of outcomes measurement to mental health services. Aust. Health Rev. Publ. Aust. Hosp. Assoc. 2001, 24, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaly, T.; Hyland, M.; Coombs, T.; Trauer, T. Routine outcome measurement in public mental health: Results of a clinician survey. Aust. Health Rev. Publ. Aust. Hosp. Assoc. 2006, 30, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Lewis, T.; McIntosh, P.; Callaly, T.; Coombs, T.; Hunter, A.; Moore, L. It’s not that bad: The views of consumers and carers about routine outcome measurement in mental health. Aust. Health Rev. Publ. Aust. Hosp. Assoc. 2009, 33, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Chaney, E.; Shoai, R.; Bonner, L.; Cohen, A.N.; Doebbeling, B.; Dorr, D.; Goldstein, M.K.; Kerr, E.; Nichol, P. Information technology to support improved care for chronic illness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.G.; Hedeker, D.; Peterson, J.L.; Davis, J.M. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997, 42, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.J.; Ngor, E.; Reynolds, K.; Quinn, V.P.; Koebnick, C.; Young, D.R.; Sternfeld, B.; Sallis, R.E. Initial validation of an exercise vital sign in electronic medical records. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 2071–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, A.M.; Bernstein, I.H.; Greer, T.L.; Walker, R.; Rethorst, C.D.; Grannemann, B.; Carmody, T.; Trivedi, M.H. Self-rated measure of pain frequency, intensity, and burden: Psychometric properties of a new instrument for the assessment of pain. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 59, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.C.; Schmidt, S.M.; Allensworth-Davies, D.; Saitz, R. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.C.; Schmidt, S.M.; Allensworth-Davies, D.; Saitz, R. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M.C.; Zbrozek, A.S.; Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993, 4, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Morris, D.W.; Fava, M.; Kurian, B.T.; Gollan, J.K.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Warden, D.; Gaynes, B.N.; Luther, J.F.; et al. Concise Associated Symptoms Tracking scale: A brief self-report and clinician rating of symptoms associated with suicidality. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Minhajuddin, A.; South, C.; Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H. Worsening Anxiety, Irritability, Insomnia, or Panic Predicts Poorer Antidepressant Treatment Outcomes: Clinical Utility and Validation of the Concise Associated Symptom Tracking (CAST) Scale. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 21, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Morris, D.W.; Fava, M.; Gollan, J.K.; Warden, D.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Gaynes, B.N.; Husain, M.M.; Luther, J.F.; et al. Concise Health Risk Tracking scale: A brief self-report and clinician rating of suicidal risk. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombello, J.M.; Killian, M.O.; Grannemann, B.D.; Rush, A.J.; Mayes, T.L.; Parsey, R.V.; McInnis, M.; Jha, M.K.; Ali, A.; McGrath, P.J.; et al. The Concise Health Risk Tracking-Self Report: Psychometrics within a placebo-controlled antidepressant trial among depressed outpatients. J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, K.; Killian, M.O.; Mayes, T.L.; Greer, T.L.; Trombello, J.M.; Lindblad, R.; Grannemann, B.D.; Carmody, T.J.; Rush, A.J.; Walker, R.; et al. A psychometric evaluation of the Concise Health Risk Tracking Self-Report (CHRT-SR)-a measure of suicidality-in patients with stimulant use disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 102, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostacher, M.J.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rabideau, D.; Reilly-Harrington, N.A.; Sylvia, L.G.; Gold, A.K.; Shesler, L.W.; Ketter, T.A.; Bowden, C.L.; Calabrese, J.R.; et al. A clinical measure of suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, and associated symptoms in bipolar disorder: Psychometric properties of the Concise Health Risk Tracking Self-Report (CHRT-SR). J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 71, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Qamar, A.; Vaduganathan, M.; Charney, D.S.; Murrough, J.W. Screening and Management of Depression in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1827–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, H.A. The drug abuse screening test. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selzer, M.L. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1971, 127, 1653–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, D.-A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Warden, D.; Trivedi, M.H.; Carmody, T.; Toups, M.; Zisook, S.; Lesser, I.; Myers, A.; Kurian, K.R.; Morris, D.; Rush, A.J. Adherence to antidepressant combinations and monotherapy for major depressive disorder: A CO-MED report of measurement-based care. J. Psychiatry Pract. 2014, 20, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, S.R.; Rush, A.J.; Balasubramani, G.K.; Trivedi, M.H.; Nierenberg, A.A. Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006, 12, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalnik, F.; Sanchez, K.; Faria, A.; Grannemann, B.; Jha, M.; Tovian, C.; Clark, E.W.; Levinson, S.; Pipes, R.; Pederson, M.; et al. Improving the Identification and Treatment of Depression in Low-Income Primary Care Clinics: A Qualitative Study of Providers in the VitalSign6 Program; International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howe-Martin, L.; Jester, B.; Walker, R.; de la Garza, N.; Jha, M.K.; Tovian, C.; Levinson, S.; Argenbright, K.E.; Trivedi, M.H. A pilot program for implementing mental health screening, assessment, and navigation in a community-based cancer center. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe-Martin, L.; Lawrence, S.L.; Jester, B.; Garza Ndl Benedetto, N.; Benedetto, N.; Mazour, T.; Walker, R.; Jha, M.; Argenbright, K.E.; Trivedi, M.H. Implementing mental health screening, assessment, and navigation program in a community-based survivorship program. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombello, J.M.; South, C.; Cecil, A.; Sanchez, K.E.; Sanchez, A.C.; Eidelman, S.L.; Mayes, T.L.; Kahalnik, F.; Tovian, C.; Kennard, B.D.; et al. Efficacy of a Behavioral Activation Teletherapy Intervention to Treat Depression and Anxiety in Primary Care VitalSign6 Program. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombello, J.M.; Trivedi, M.H. E-behavioral Activation in Primary Care for Depression: A Measurement-Based Remission-Focused Treatment; Dimidjian, S., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, L.M.; Snyder, D.; Ludi, E.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Kohn-Godbout, J.; Lee, L.; Cartledge, T.; Farrar, A.; Pao, M. Ask suicide-screening questions to everyone in medical settings: The asQ’em Quality Improvement Project. Psychosomatics 2013, 54, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Grannemann, B.D.; Clark, E.W.; Levinson, S.; Lawson, T.; Trombello, J. A Structured Approach for Universal Screening of Depression and Measurement-Based Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Primary Care Clinics. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Clinical Tasks | Methods | Challenges | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Detect depression | Administer PHQ-2 | Documented on paper | Document directly in electronic health record (EHR) |

| Results not readily available to providers | Results routed directly to providers in EHR | |||

| Positive PHQ-2 should be followed by PHQ-9 | Screen automatically expands to PHQ-9 | |||

| Repeat screens as depression is episodic | Negative screens are re-screened annually | |||

| Diagnosis | Confirm or rule out depressive disorder | DSM-5 criteria-driven diagnostic interview | Lack of comfort with diagnostic interview | Online and in-person training |

| Diagnose based on overall clinical impression | Use DSM-5 checklist embedded in EHR | |||

| Specialist input needed for complicated cases | Access to consulting clinicians and referral sources | |||

| Treatment Selection | Shared decision-making options:

| Provider training and patient education | Frequent in-person visits for active surveillance | Remote assessments and provider review in EHR |

| Lack of comfort with prescribing antidepressants | Online and in-person training | |||

| Limited access to evidence-based psychotherapy | Tele-health programs for psychotherapy | |||

| Limited knowledge of exercise prescription | Consultation with exercise specialists | |||

| Optimize pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy | PCPs closely collaborate with tele-health therapist | |||

| Treatment Implementation | Deliver treatment Measure outcomes Assess response | Measurement-Based Care (MBC) | Assess improvement with treatment | Validated measures of symptom and functioning |

| Limited time for clinician assessments | Use of self-report assessments | |||

| Poor adherence to prescribed treatment | Systematically assess adherence at each visit | |||

| Side-effects results in treatment discontinuation | Systematic assessment of side effects at each visit | |||

| Inability to find previous paper forms | Easily searchable results in an electronic format | |||

| Unable to visualize changes over time | Custom reports for outcomes over time | |||

| Patient barriers prevent consistent follow-up | Implement patient navigation programs | |||

| Treatment Revision | Based on response | Clinical Decision Support System | How to handle treatment-resistant depression? | In-person or phone consultation; refer to specialist |

| Indicator | Metric | |

| Reach | Clinician/staff participation | Number participating/total number of clinicians/staff at clinic |

| Patient participation (screening rate) | Number screened/total number of unique patients at clinic | |

| Efficacy | Remission rates | PHQ-9 score < 5: acute-phase (18 weeks); long-term (1 year) |

| Impact on comorbid medical conditions | Exploratory analyses | |

| Adoption | Adoption of depression screening and MBC implementation | Semi-structured clinician and staff interviews |

| Implementation | Completion of MBC measures at follow-up visits | Number who completed follow-up measures/total number of patients who were due for follow-up assessments |

| Characteristics of patients who do not return for visits (“lost to care”) | Out-reach and semi-structured interviews | |

| Maintenance | Patient-level sustainability | Sustained remission over 5 or 10 years |

| Program-level sustainability | Follow-up surveys and semi-structured interviews |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trivedi, M.H.; Jha, M.K.; Kahalnik, F.; Pipes, R.; Levinson, S.; Lawson, T.; Rush, A.J.; Trombello, J.M.; Grannemann, B.; Tovian, C.; et al. VitalSign6: A Primary Care First (PCP-First) Model for Universal Screening and Measurement-Based Care for Depression. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph12020071

Trivedi MH, Jha MK, Kahalnik F, Pipes R, Levinson S, Lawson T, Rush AJ, Trombello JM, Grannemann B, Tovian C, et al. VitalSign6: A Primary Care First (PCP-First) Model for Universal Screening and Measurement-Based Care for Depression. Pharmaceuticals. 2019; 12(2):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph12020071

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrivedi, Madhukar H., Manish K. Jha, Farra Kahalnik, Ronny Pipes, Sara Levinson, Tiffany Lawson, A. John Rush, Joseph M. Trombello, Bruce Grannemann, Corey Tovian, and et al. 2019. "VitalSign6: A Primary Care First (PCP-First) Model for Universal Screening and Measurement-Based Care for Depression" Pharmaceuticals 12, no. 2: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph12020071

APA StyleTrivedi, M. H., Jha, M. K., Kahalnik, F., Pipes, R., Levinson, S., Lawson, T., Rush, A. J., Trombello, J. M., Grannemann, B., Tovian, C., Kinney, R., Clark, E. W., & Greer, T. L. (2019). VitalSign6: A Primary Care First (PCP-First) Model for Universal Screening and Measurement-Based Care for Depression. Pharmaceuticals, 12(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph12020071