Fluid Pressure Sensing Strategy Suitable for Swallowing Soft Gripper

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design and Method

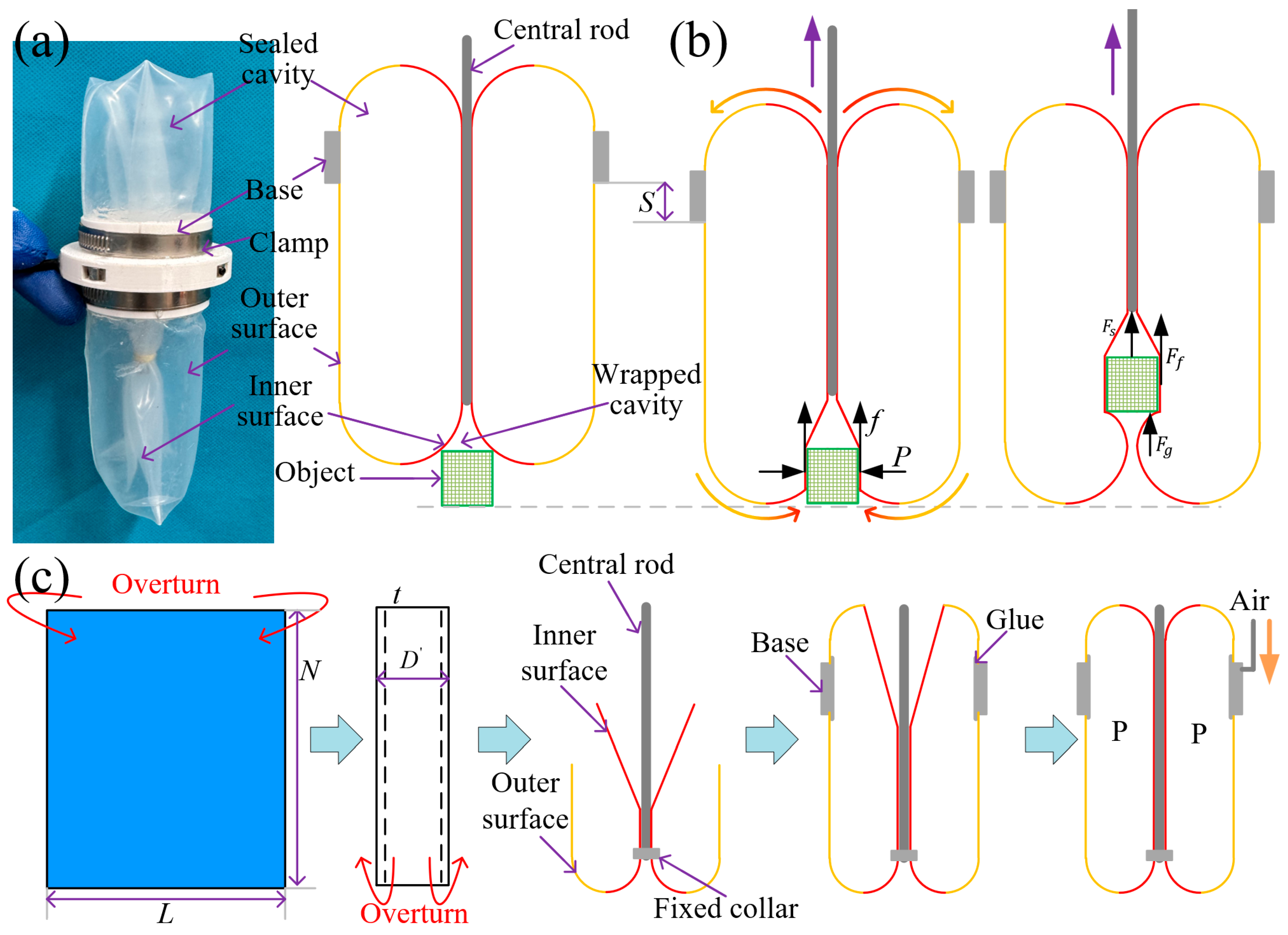

2.1. Principle Prototype of the Swallowing Gripper

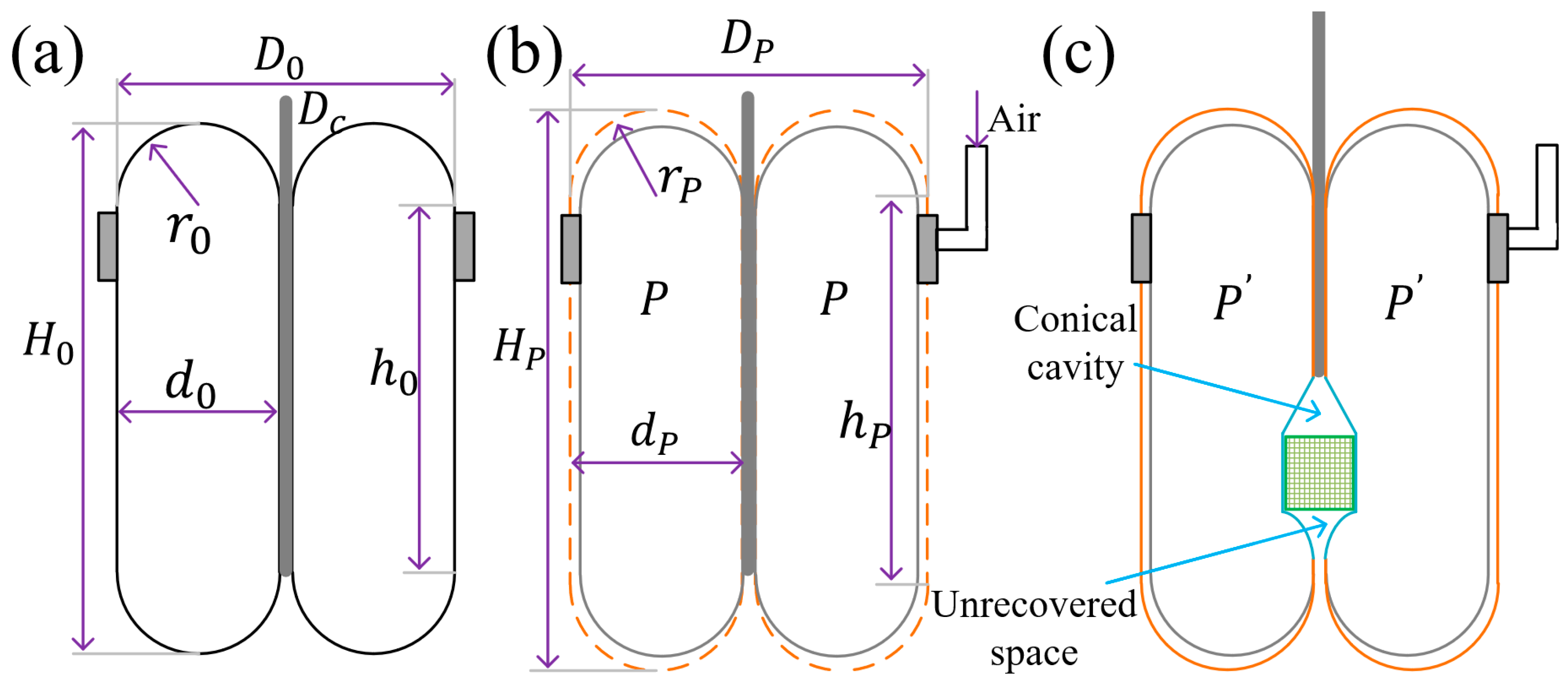

2.2. Analysis and Modeling of the Elastic Membrane

2.3. Establishment of the Swallowing Sensing Model

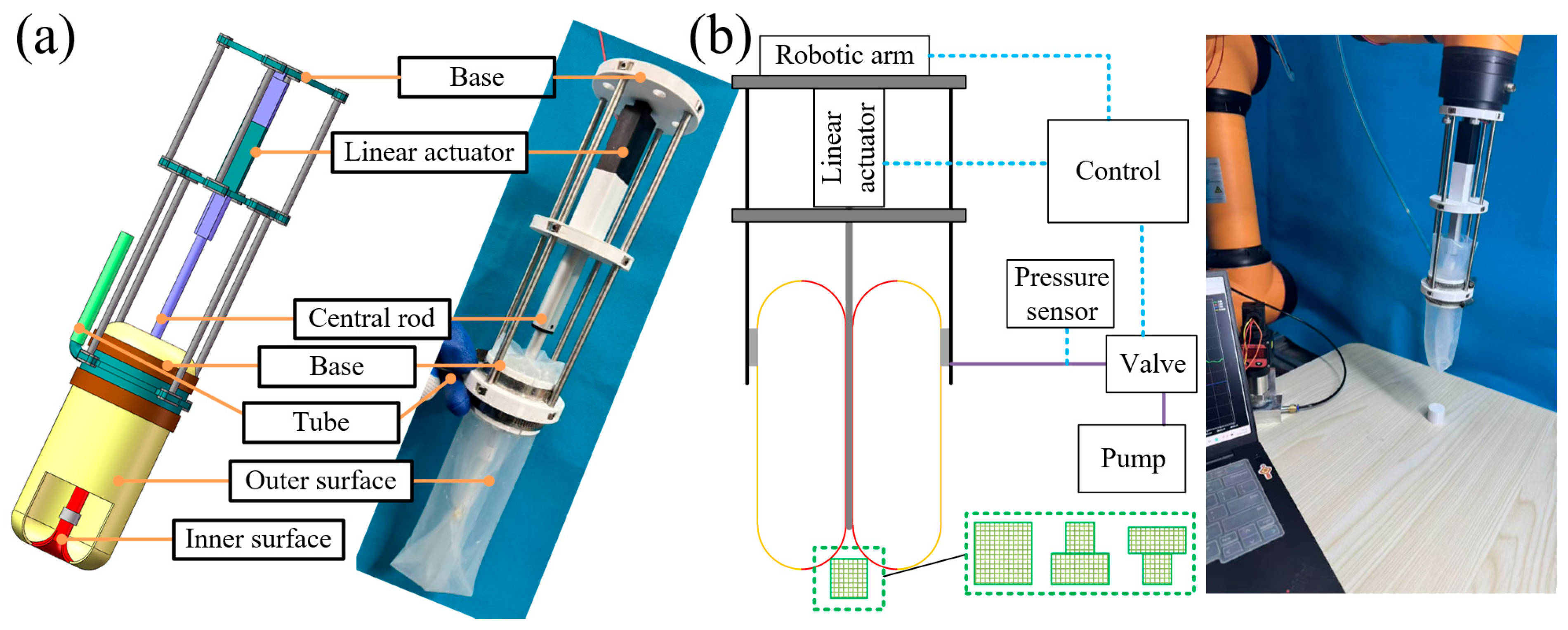

3. Experiments and Results

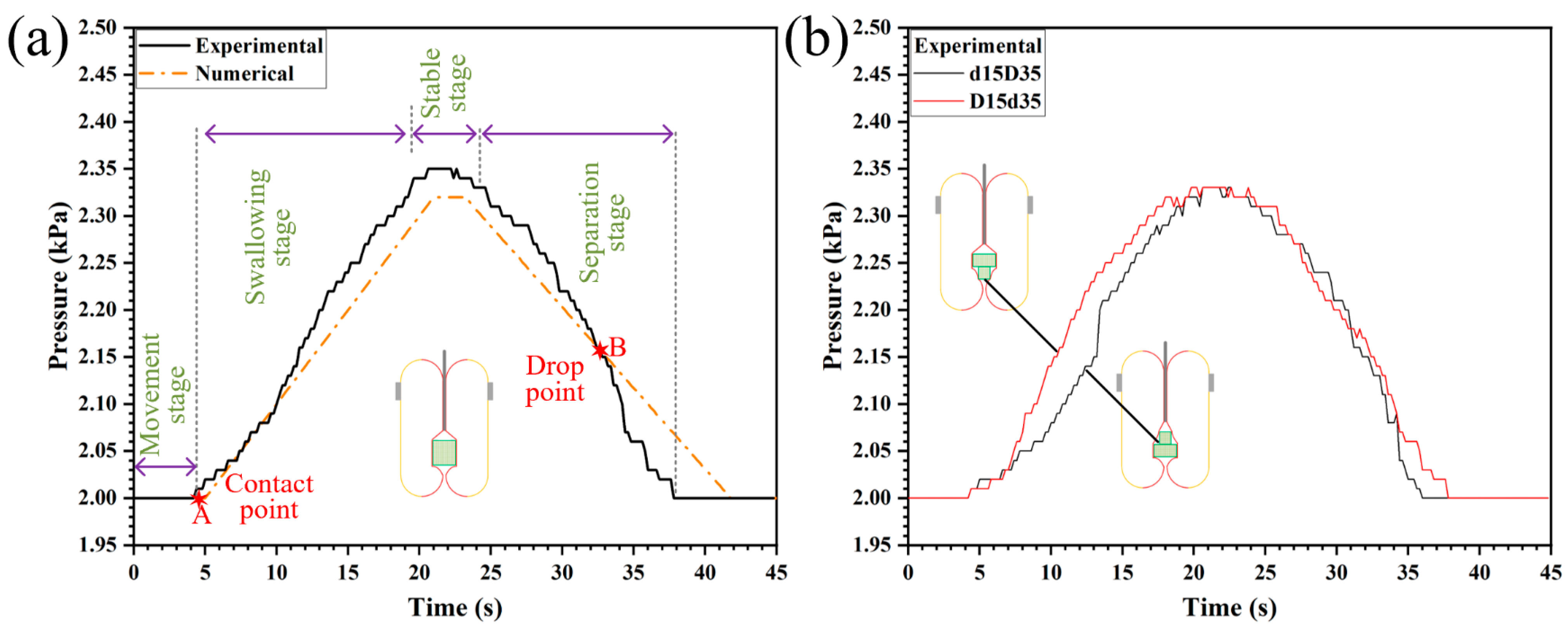

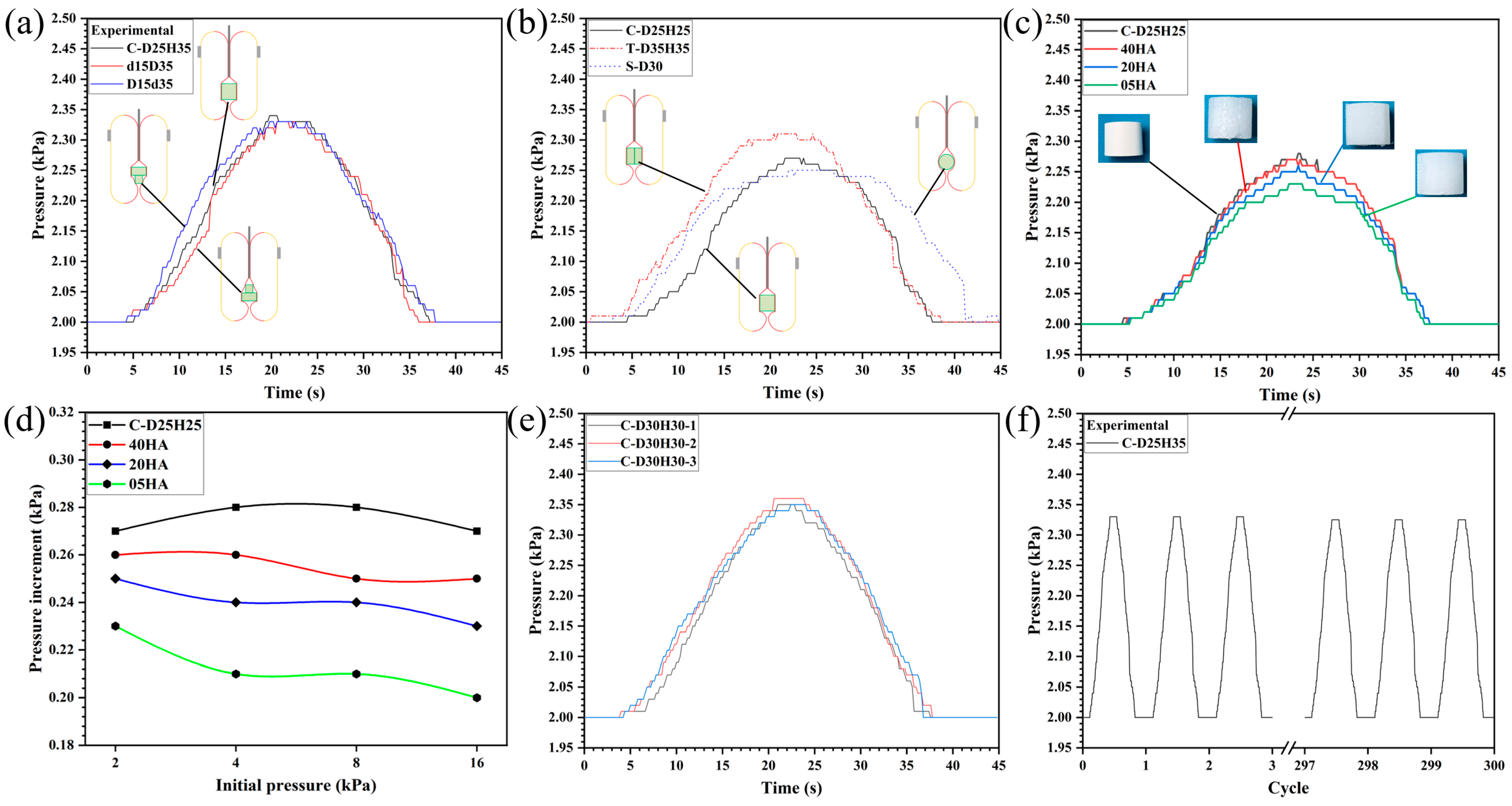

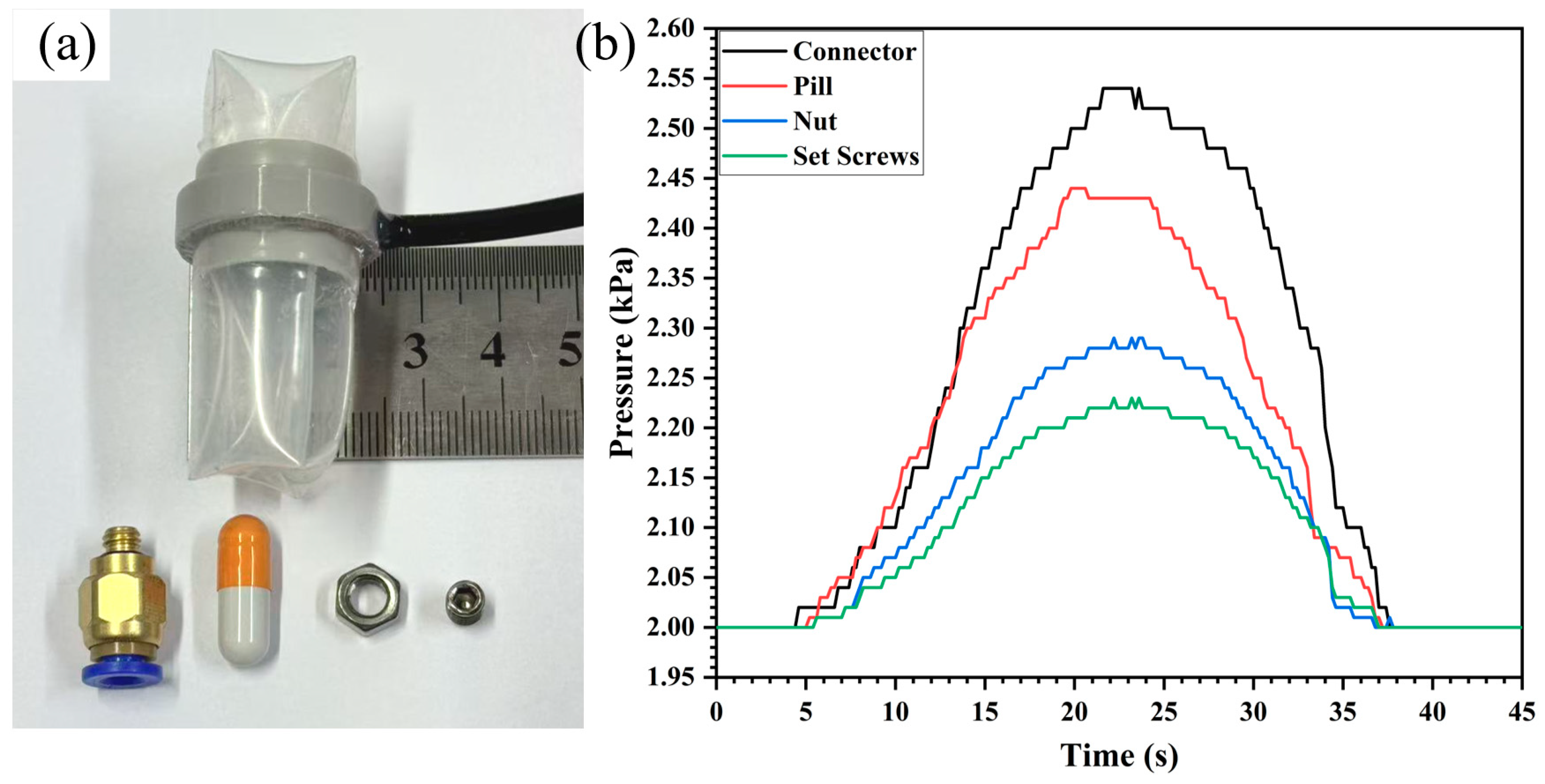

3.1. Sensing Performance Testing

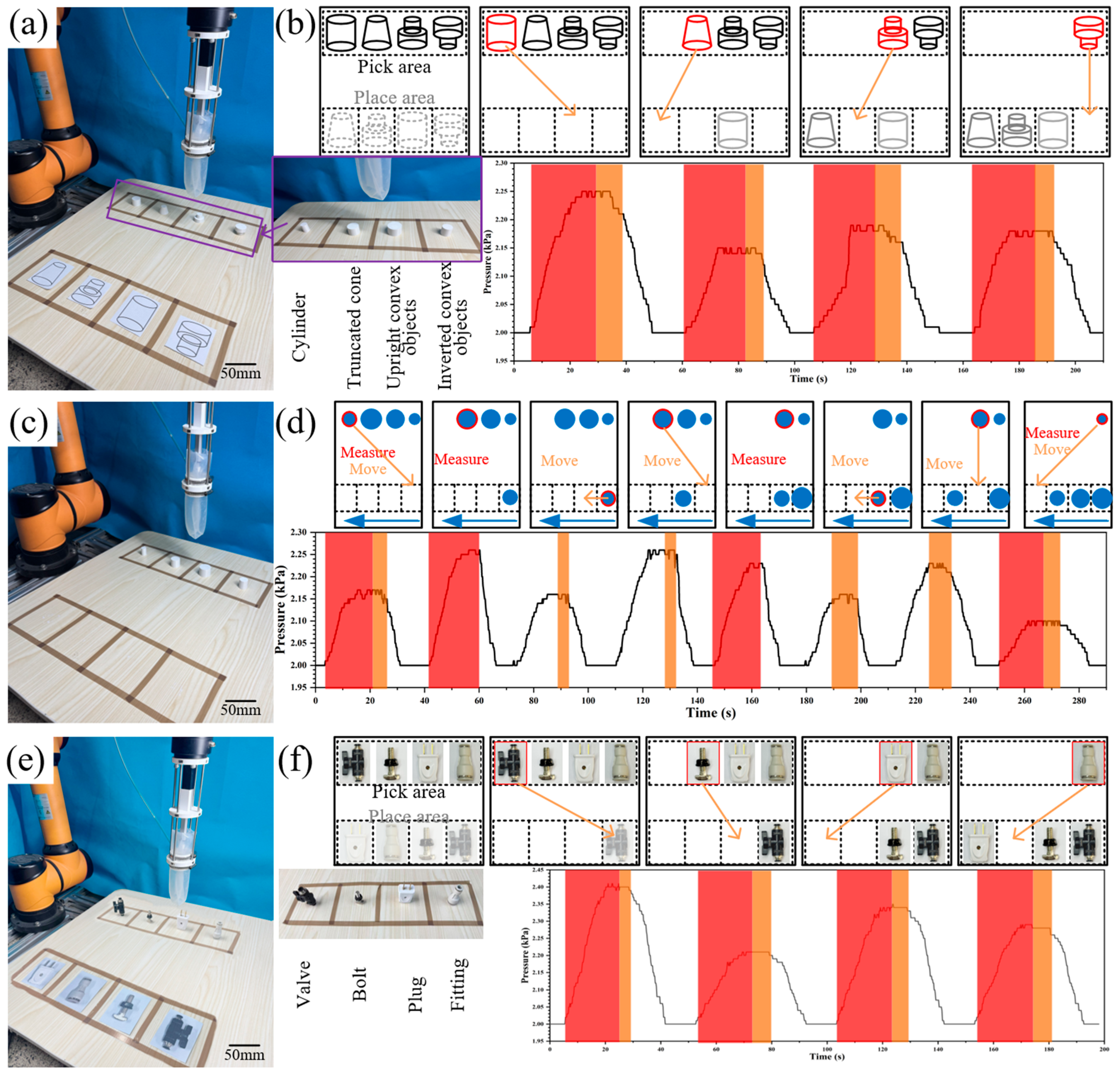

3.2. Closed-Loop Control with Fluidic Sensing

3.3. Verification of Size Independence

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shintake, J.; Cacucciolo, V.; Floreano, D.; Shea, H. Soft Robotic Grippers. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ren, L.; Chen, Y.; Niu, S.; Han, Z.; Ren, L. Bio-Inspired Soft Grippers Based on Impactive Gripping. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Chang, U.; Lu, J.-T.; Leung, C.C.Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z. A Soft-Robotic Approach to Anthropomorphic Robotic Hand Dexterity. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 101483–101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; O’Brien, K.; Li, S.; Shepherd, R.F. Optoelectronically Innervated Soft Prosthetic Hand via Stretchable Optical Waveguides. Sci. Robot. 2016, 1, eaai7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kan, Z.; Zeng, J.; Wang, M.Y. Hybrid Jamming for Bioinspired Soft Robotic Fingers. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q. Natural Entanglement Inspired Cilia-Like Soft Gripper for Rapid Adaptive Grasping. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 8, 2500468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yao, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, K.; Kong, S.; Qi, S.; Zhang, X. WebGripper: Bioinspired Cobweb Soft Gripper for Adaptable and Stable Grasping. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Biswas, S.; Hawkes, E.W.; Wang, T.; Zhu, M.; Wen, L.; Visell, Y. A Multimodal, Enveloping Soft Gripper: Shape Conformation, Bioinspired Adhesion, and Expansion-Driven Suction. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, X.; Sun, C.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X. 3D Printing of Octopi-Inspired Hydrogel Suckers with Underwater Adaptation for Reversible Adhesion. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Lu, C.; Tang, K.; Qi, Q.; Lu, Z.; Lee, L.Y.; Bloomfield-Gadȇlha, H.; Rossiter, J. Embodying Soft Robots with Octopus-Inspired Hierarchical Suction Intelligence. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadr4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W. A Spherical Self-Adaptive Gripper with Shrinking of an Elastic Membrane. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), Macau, China, 18–20 August 2016; pp. 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, H.; Liao, B.; Lang, X.; Zhao, Z.-L.; Yuan, W.; Feng, X.-Q. Bionic Torus as a Self-Adaptive Soft Grasper in Robots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 023701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, T.; Agrawal, S.K.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J. A Bioinspired Soft Swallowing Gripper for Universal Adaptable Grasping. Soft Robot. 2022, 9, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, P.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y. A Bioinspired Soft Swallowing Robot Based on Compliant Guiding Structure. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Huang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yin, Z. A Variable Stiffness Bioinspired Swallowing Gripper Based on Particle Jamming. Soft Robot. 2025, 12, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Zhang, W.; Jang, H.; Kang, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, P.; Hwang, H.; Lu, N. Highly Sensitive Capacitive Pressure Sensors over a Wide Pressure Range Enabled by the Hybrid Responses of a Highly Porous Nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Nie, H.-Y. Design and Fabrication of Flexible Capacitive Sensor with Cellular Structured Dielectric Layer via 3D Printing. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 10473–10482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cooper, L.P.; Liu, N.; Wang, X.; Fok, M.P. Twining Plant Inspired Pneumatic Soft Robotic Spiral Gripper with a Fiber Optic Twisting Sensor. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 35158–35167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, W.; Song, C.; Pan, J.; Shen, Y. Soft Magnetic Skin for Super-Resolution Tactile Sensing with Force Self-Decoupling. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabc8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Picella, S.; de Vries, J.; Kortman, V.G.; Sakes, A.; Overvelde, J.T.B. A Retrofit Sensing Strategy for Soft Fluidic Robots. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barvenik, K.; Coogan, Z.; Librandi, G.; Pezzulla, M.; Tubaldi, E. Tactile Sensing and Grasping Through Thin-Shell Buckling. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 2300855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Paik, J. Sensorless Force and Displacement Estimation in Soft Actuators. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 2554–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, A.E.; Seifi, H.; Hilliges, O.; Gassert, R.; Kuchenbecker, K.J. In the Arms of a Robot: Designing Autonomous Hugging Robots with Intra-Hug Gestures. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot Interact. 2023, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, R.L.; Chin, L.; Zhang, A.; Rus, D. Fluidic Innervation Sensorizes Structures from a Single Build Material. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawk, C.; Sariyildiz, E.; Alici, G. Force Control of a 3D Printed Soft Gripper with Built-In Pneumatic Touch Sensing Chambers. Soft Robot 2022, 9, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Mechanoreception for Soft Robots via Intuitive Body Cues. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; He, R.; Yu, J.; Zuo, G.; Gong, D.; He, R.; Yu, J.; Zuo, G. A Pneumatic Tactile Sensor for Co-Operative Robots. Sensors 2017, 17, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Yin, Z. Fluid Pressure Sensing Strategy Suitable for Swallowing Soft Gripper. Sensors 2026, 26, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030960

Li M, Zhang W, Liu Q, Yin Z. Fluid Pressure Sensing Strategy Suitable for Swallowing Soft Gripper. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030960

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mingge, Wenxi Zhang, Quan Liu, and Zhongjun Yin. 2026. "Fluid Pressure Sensing Strategy Suitable for Swallowing Soft Gripper" Sensors 26, no. 3: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030960

APA StyleLi, M., Zhang, W., Liu, Q., & Yin, Z. (2026). Fluid Pressure Sensing Strategy Suitable for Swallowing Soft Gripper. Sensors, 26(3), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030960